Vol. 2, P. 473-515

Of The Argo, and Argonautic Expedition

"The season of Sisira is from the first of Dhanishtha to the middle of Revati; that of Vasanta from the middle of Revati to the end of Rohini; that of Grishma from the beginning of Mrigasiras to the middle of Aslesha; that of Versha from the middle of Aslesha to the end of Hasta; that of Sanad from the first of Chitra to the middle of Jyeshtha; that of Hemanta from the middle of Jyeshtha to the end of Sravana."

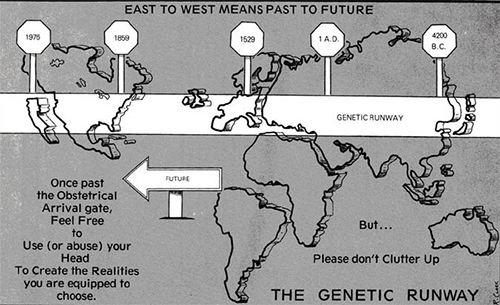

This account of the six Indian seasons, each of which is co-extensive with two signs, or four lunar stations and a half, places the solstitial points, as Varaha has asserted, in the first degree of Dhanishtha, and the middle, or 6°40', of Aslesha, while the equinoctial points were in the tenth degree of Bharani and 3°20' of Visacha; but in the time of Varaha, the solstitial colure passed through the 10th degree of Punarvasu and 3°20' of Uttarashara, while the equinoctial colure cut the Hindu ecliptic in the first of Aswini and 6°40' of Chitra, or the Yoga and only star of that mansion, which, by the way, is indubitably the Spike of the Virgin, from the known longitude of which all other points in the Indian Zodiac may be computed. It cannot escape notice, that Parasara does not use in this passage the phrase at present, which occurs in the text of Varaha; so that the places of the colures might have been ascertained before his time, and a considerable change might have happened in their true position without any change in the phrases by which the seasons were distinguished; as our popular language in astronomy remains unaltered, though the Zodiacal asterisms are now removed a whole sign from the places where they have left their names. It is manifest, nevertheless, that Parasara must have written within twelve centuries before the beginning of our era, and that single fact, as we shall presently show, leads to very momentous consequences in regard to the system of Indian history and literature.

On the comparison which might easily be made between the colures of Parasar and those ascribed by Eudoxus to Chiron, the supposed assistant and instructor of the Argonauts, I shall say very little; because the whole Argonautic story, (which neither was, according to Herodotus, nor, indeed, could have been originally Grecian) appears, even when stripped of its poetical and fabulous ornaments, extremely disputable; and whether it was founded on a league of the Helladian princes and states for the purpose of checking, on a favourable opportunity, the overgrown power of Egypt, or with a view to secure the commerce of the Euxine and appropriate the wealth of Colchis; or, as I am disposed to believe, on an emigration from Africa find Asia of that adventurous race, who had first been established in Chaldea; whatever, in short, gave rise to the fable, which the old poets have so richly embellished, and the old historians have so inconsiderately adopted, it seems to me very clear, even on the principles of Newton, and on the same authorities to which he refers, that the voyage of the Argonauts must have preceded the year in which his calculations led him to place it.[!!!]

-- XXVII. A Supplement to the Essay on Indian Chronology, by the President (Sir William Jones), Asiatic Researches, Volume 2, 1788

Nor shall I meddle with Sir Isaac Newton's astronomical argument for fixing the time of the Argonautic expedition (and of course the time of the fall of Troy, which was only one generation later), from the position of the solstitial and equinoctial points on the sphere which Chiron made for the use of the Argonauts. I am too little acquainted with the science of astronomy to speak pertinently on the subject. I shall only observe that Mr. Whiston does not agree with Dr. Shuckford concerning the grounds of the argument.

"The fallacy of this argument (says Dr. Shuckford) cannot but appear very evident to any one that attends to it: for suppose we allow that Chiron did really place the solstices, as Sir Isaac Newton represents (though I should think it most probable that he did not so place them), yet it must be undeniably plain, that nothing can be certainly established from Chiron's position of them, unless it appears, that Chiron knew how to give them their true place."If indeed it could be known what was the true place of the solstitial points in Chiron's time, it might be known, by taking the distance of that place from the present position of them, how much time has elapsed from Chiron to our days.

But I answer, it cannot be accurately known from any schemes of Chiron what was the true place of the solstices in his days; because, though it is said that he calculated the then position of them, yet he was so inaccurate an astronomer, that his calculation might err four or five degrees from their true position."

Mr. Whiston (p. 991) writes thus:"As to the first argument from the place of the two colures in Eudoxus from Chiron the Argonaut, preserved by Hipparchus of Bithynia, I readily allow its foundation to be true, that Eudoxus's sphere was the same with Chiron's, and that it was first made and showed Hercules and the rest of the Argonauts in order to guide them in their voyage to Colchis. And I take the discovery of this sure astronomical criterion of the true time of that Argonautic expedition (in the defect of eclipses) to be highly worthy the uncommon sagacity of the great Sir Isaac Newton, and in its own nature a chronological character truly inestimable. Nor need we, I think, any stronger argument in order to overturn Sir Isaac Newton's own Chronology, than this position of the colures at the time of that expedition, which its proposer has very kindly furnished us withal."

In p. 996:I now proceed to Eudoxus's accurate description of the position of the two colures as they had been drawn on their celestial globes, ever since the days of Chiron, at the Argonautic expedition, and as Hipparchus has given us that description in the words of Eudoxus."

Again (p. 1002):"Sir Isaac Newton betrays his consciousness how little Eudoxus's description of Chiron's colures agreed to his position of them, by pretending that these observations of the ancients were coarse and inaccurate. This is true if compared with the observations of the moderns which read to minutes; and, since, the application of telescopic sights to astronomic instruments, to ten or fewer seconds. But as to our present purpose this description in Eudoxus is very accurate, it both taking notice of every constellation, through which each of the coloures passed, that were visible in Greece; and hardly admitting of an error of half a degree in angular measures, or thirty-six years in time. Which is sufficiently exact."

How far Mr. Whiston has succeeded in his argumentation about the neck of the swan and the tail of the bear, &c. I must leave to others to consider. I shall only observe, with regard to the last paragraph cited from his discourse, that when Sir Isaac Newton calls the observations of the ancient astronomers coarse, he cannot well be understood to use that word but in a comparative sense, that sense in which Mr. Whiston admits it may be justly used. For otherwise Sir Isaac would not have inferred any thing as certain from those ancient observations. Now, in p. 95, after he has finished his argument from Chiron's sphere, he thus writes:"Hesiod tells us, that sixty days after the winter solstice, the star Arcturus rose at sunset: and thence it follows, that Hesiod flourished about 100 years after the death of Solomon, or in the generation or age next after the Trojan war, as Hesiod himself declares.

From all these circumstances, grounded upon the coarse observations of the ancient astronomers, we may reckon it certain, that the Argonautic expedition was not earlier than the reign of Solomon: and if these astronomical arguments be added to the former arguments taken from the mean length of the reigns of kings according to the course of nature; from them all we may safety conclude, that the Argonautic expedition was after the death of Solomon, and most probably that it was about forty-three years after.

The Trojan war was one generation later than that expedition -- several captains of the Greeks in that war being sons of the Argonauts,"

&c.

By the last words here cited, I am brought round again to the point from whence I set out in this discourse, the fall of Troy...

-- Remarks on the History of the Seven Roman Kings, Occasioned by Sir Isaac Newton’s Objections to the Supposed Two Hundred and Forty-Four Years’ Duration of the Regal State of Rome, from The Roman History From the Building of Rome to the Ruin of the Commonwealth, Illustrated with Maps, by N. Hooke, Esq., 1823

[x]. Palaephatus.

My purpose has been universally to examine the ancient mythology of Greece; and by diligently collating the evidences afforded, to find out the latent meaning. I have repeatedly taken notice, that the Grecians formed variety of personages out of titles, and terms unknown: many also took their rise from hieroglyphics misinterpreted. The examples, which I have produced, will make the reader more favourably inclined to the process, upon which I am about to proceed. Had I not in this manner opened the way to this disquisition, I should have been searful of engaging in the pursuit. For the history of the Argonauts, and their voyage, has been always esteemed authentic, and admitted as a chronological aera. Yet it may be worth while to make some inquiry into this memorable transaction; and to see if it deserves the credit, with which it has been hitherto favoured. Some references to this expedition are interspersed in most of the writings of the1 [The principal are those, which follow. (1) Author of the Orphic Argonautica; (2) Apollonius Rhodius; (3) Valerius Flaccus; (4) Diodorus Siculus. L. 4. p. 245; (5) Ovid. Metamorphosis. L. 7; (6) Pindar, Pyth. Ode 4; (7) Apollodorus. L. I. p. 4; (8) Strabo. L. 3. p. 222; (9) Hyginus. Fab. 14. p. 38.] ancients. But beside these scattered allusions, there are compleat histories transmitted concerning it: wherein writers have enumerated every circumstance of the operation.

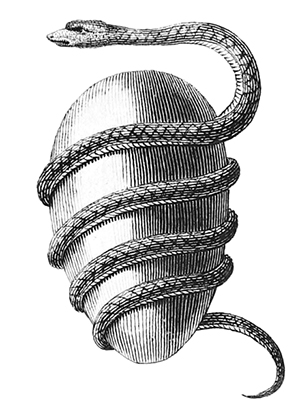

By these writers we are informed, that the intention of this armament was to bring back a golden fleece, which was detained by AEetes king of Colchis. It was the fleece of that ram on which Phrixus and2 [Hyginus. Fab. 2. p. 18. Pausan. L. 9. p. 778.] Helle fled to avoid the anger of Ino. They were the two children of Athamas, conceived by ([x]) a cloud: and their brother was Learchus. The ram, upon which they escaped, is represented, as the son of3 [Hyginus, Fab. 3. p. 21.] Neptune and Theophane. Upon his arrival at Colchis Phrixus sacrificed it to Mars, in whose temple the fleece was suspended. Helle was supposed to have fallen into the sea, called afterwards the Hellespont, and to have been drowned. After an interval of some years, Pelias, king of Jolchus, commissioned Jason, the son of his brother AEson, to go, and recover this precious fleece. To effect this a ship was built at Pagasae, which city lay at no great distance from Mount Pelion in Thessaly. It was the first that was ever attempted; and the merit of the performance is given to Argus, who was instructed by Minerva, or divine wisdom. This ship was built partly out of some sacred timber from the grove of Dodona, which was sacred to Jupiter Tomarias. On this account it was said to have been oracular, and to have given verbal responses; which history is beautifully described by Claudian.4 [De Bello Getico. V. 16. [x]. Orph. Argonautica. V. 1153.]

Argois trabibus jactant sudasse Minervam:

Nec nemoris tantum vinxisse carentia sensu

Robora; sed, caeso Tomari Jovis augure luco,

Arbore praefaga tabulas animasse Ioquaces.

[Google translate: They boast that Minerva had sweated on Argo's beams;

Nor was the wood so complicated by the lack of sense

Encourage but, after the grove of Jupiter the augur Tomari had been slain,

The prefaced tree frames have encouraged the gossip.]

As soon as this sacred machine was compleated, a select band of heroes, the prime of their age and country, met together, and engaged in this honourable enterprize. Among these Jason was the chief; by whom the others were summoned, and collected. Chiron, who was famous for his knowledge, and had instructed many of those young heroes in science, now framed for their use a delineation of the heavens: though some give the merit of this operation to Musaeus. This was the first sphere constructed: in which the stars were formed into asterisms for the benefit of the Argonauts; that they might be the better able to conduct themselves in their perilous voyage. The heroes being all assembled, waited for the rising of the Peleiades; at which season they set5 [[x]. Theoc. Idyl. 13. v. 25.] sail. Writers differ greatly about the rout, which they took at their setting out; as well as about the way of their return. The general account is, that they coasted Macedonia, and proceeded to Thrace; where Hercules engaged with the giants; as he is supposed to have done in many other places. They visited Lemnos, and Cyzicus; and from thence came to the Bosporus. Here were two rocks called the Cyanean, and also the Symplegades; which used to clash together with a mighty noise, and intercept whatever was passing. The Argonauts let a Dove fly, to see by her fate, if there were a possibility of escaping. The Dove got through with some difficulty; encouraged by which omen the heroes pressed forward; and by the help of Minerva escaped. After many adventures, which by the Poets are described in a manner wonderfully pleasing, they arrive at the Phasis, which was the chief river of Colchis. They immediately address AEetes; and after having informed him concerning the cause of their coming, demand a restitution of the fleece. The king was exasperated at their claim; and resused to give up the object in view, but upon such terms, as seemed impracticable. Jason however accepted of the conditions: and after having engaged in many labours, and by the assistance of Medea soothed a sleepless dragon, which guarded the fleece, he at last brought off the prize. This being happily effected, he retired privately to his ship, and immediately set sail; at the same time bringing away Medea, the king's daughter. As soon as AEetes was apprized of their flight, he fitted out some ships to pursue them: and arriving at the Thracian Bosporus took possession of that pass. The Argonauts having their retreat precluded, returned by another rout, which by writers is differently represented. Upon their arrival in Greece they offered sacrifices to the Gods; and consecrated their ship to Neptune.

What is alluded to in this romantic detail, may not perhaps at first sight be obvious. The main plot, as it is transmitted to us, is certainly a fable, and replete with inconsistency and contradiction. Yet many writers have taken the account in gross: and without hesitation, or exception to any particular part, have presumed to fix the time of this transaction. And having satisfied themselves in this point, they have proceeded to make use of it for a stated aera. Hence many inferences, and deductions have been formed, and many events have been determined, by the time of this fanciful adventure. Among the most eminent of old, who admitted it as an historical truth, were Herodotus, Diodorus, Strabo; and with them every Grecian Mythologist: of the fathers, Clemens, Eusebius, and Syncellus. Among the moderns, the principal are Scaliger and Petavius: and of our country, Archbishop Usher, Cumberland, Dr. Jackson, and Sir Isaac Newton, This last speaks of it without any difsidence; and draws from it many consequences, as from an event agreed upon, and not to be questioned: an aera, to which we may safely refer. It was a great misfortune to the learned world, that this excellent person was so easily satisfied with Grecian lore; taking with too little examination, whatever was transmitted to his hands. By these means many events of great consequence are determined from very uncertain and exceptionable data. Had he Iooked more carefully into the histories, to which he appeals, and discarded, what he could not authenticate; such were in all other respects his superior parts, and penetration, that he would have been as eminent for moral evidence, as he had been for demonstration. This last was his great prerogative, which when he quitted, he became like Sampson shorn of his strength; he went out like another man. This history, upon which he builds so much, was founded upon some ancient traditions, but misinterpreted greatly. It certainly did not relate to Greece; though adopted by the people of that country. Sir Isaac Newton, with great ingenuity has endeavoured to find out the time of this expedition by the place of the6 [Newton's Chronology, p, 83, 84.] Colures then, and the degrees, which they have since gone back. And this he does upon a supposition that there was such a person as Chiron: and that he really, as an ancient poet would persuade us, formed a sphere for the Argonauts.

7 [Auctor Titanomachiae apud Clementem. Strom. L. I. p. 360. [Google translate: The author of Titanomachia with Clement. Strom. L. I. p. 360.]] [x]

In answer to this the learned Dr. Rutherforth has exhibited some curious observations: in which he shews, that there is no reason to think that Chiron was the author of the sphere spoken of, or of the delineations attributed to him. Among many very just exceptions he has one, which seems to me to be very capital, and which I shall transcribe from him.8 [Rutherforth's System of Natural Philosophy. Vol. 2. p. 849.]

Beside Pagasae, from whence the Argonauts failed, is about 39°; and Colchis, to which they were failing, is in about 45° north latitude. The star Canobus of the first magnitude, marked [x] by Bayer, in the constellation Argo, is only 37° from the south pole: and great part of this constellation is still nearer to the south pole. Therefore this principal star, and great part of the constellation Argo could not be seen, either in the place, that the Argonauts set out from, or in the place, to which they were failing. Now the ship was the first of its kind; and was the principal thing in the expedition: which makes it very unlikely, that Chiron should chuse to call a set of stars by the name of Argo, most of which were invisible to the Argonauts. If he had delineated the sphere for their use, he would have chosen to call some other constellation by this name: he would most likely have given the name Argo to some constellation in the Zodiac: however, certainly, to one that was visible to the Argonauts; and not to one which was so far to the south, that the principal star in it could not be seen by them, either when they set out, or when they came to the end of their voyage.

These arguments, I think, shew plainly, that the sphere could not have been the invention of9 [Sir Isaac Newton attributes the invention of the Sphere to Chiron, or to Musaeus. Some give the merit of it to Atlas; others to Palamedes. [x] -- Sophocles in Nauplio. The chief constellation, and of the most benefit to Mariners, is the Bear with the Polar star. This is said not to have been observed by any one before Thales: the other, called the greater Bear, was taken notice of by Nauplius: [x]. Theon. in Arat. V. 27. [x]. Schol. Apollonii. L. I. v. 134.] Chiron or Musaeus; had such persons existed. But I must proceed farther upon these principles; for to my apprehension they prove most satisfactorily, that it was not at any rate a Grecian work: and that the expedition itself was not a Grecian operation. Allowing Sir Isaac Newton, what is very disputable, that many of the asterisms in the sphere relate to the Argonautic operations; yet such sphere could not have been previously constructed, as it refers to a subsequent history. Nor would an astronomer of that country in any age afterwards have so delineated a sphere, as to have the chief memorial in a manner out of sight; if the transaction to which it alluded, had related to Greece. For what the learned Dr. Rutherforth alledges in respect to Chiron and Musaeus, and to the times in which they are supposed to have lived, will hold good in respect to any Grecian in any age whatever. Had those persons, or any body of their country, been authors of such a work; they must have comprehended under a figure, and given the name of Argo to a collection of stars, with many of which they were unacquainted: consequently their Iongitude, latitude, and reciprocal distances, they could not know. Even the Egyptians seem in their sphere to have omitted those constellations, which could not be seen in their degrees of latitude, or in those which they frequented. Hence many asterisms near the southern pole, such as the Croziers, Phoenicopter, Toucan, &c. were for a long time vacant, and unformed: having never been taken notice of, till our late discoveries were made on the other side of the line. From that time they have been reduced into asterisms, and distinguished by names.

If then the sphere, as we have it delineated, was not the work of Greece, it must certainly have been the produce of10 [Diodorus says that the Sphere was the invention of Atlas; by which we are to understand the Atlantians. L, 3. p. 193.] Egypt. For the astronomy of Greece confessedly came from that11 [[x]. Herodot. L. 2. c. 4. [x] Clemens Alexand. Strom. L. I. p. 361.] country: consequently the history, to which it alludes, must have been from the same quarter. For it cannot be supposed, that in the constructing of a sphere the Egyptians would borrow from the12 [The Egyptians borrowed nothing from Greece. [x]. Herodot. L. 2. c. 49. See also Diodorus Siculus. L. I. p. 62, 63. of arts from Egypt.] Helladians, or from any people whatever: much less would they crowd it with asterisms relating to various events, in which they did not participate, and with which they could not well be acquainted: for in those early days the history of Hellas was not known to the sons of Mizraim. Many of the constellations are apparently of Egyptian original; and were designed as emblems of their Gods, and memorials of their rites and mythology. The Zodiac, which Sir Isaac Newton supposed to relate to the Argonautic expedition, was an assemblage of Egyptian hieroglyphics. Aries, which he refers to the golden fleece, was a representation of Amon: Taurus of Apis: Leo of Arez, the same as Mithras, and Osiris. Virgo with the spike of corn was13 [[x]. Eratosthenis Asterism. [x].] Isis. They called the Zodiac the grand assembly, or senate, of the twelve Gods, [x]. The planets were esteemed [x], lictors and attendants, who waited upon the chief Deity, the Sun. These, says the Scholiast upon14 [[x]. Scholia Apollon. Argon. L. 4. v. 261.] Apollonius, were the people who first observed the influences of the stars; and distinguished them by names: and from them they came to15 [[x]. Herod. L. 2. c. 49 and 50. [x]. Plato in Phaedro. v. 3. p. 274.] Greece.

Strabo, one of the wisest of the Grecians, cannot be persuaded but that the history of the Argonautic expedition was true: and he takes notice of many traditions concerning it in countries far remote: and traces of the heroes in many places; which arose from the temples, and cities, which they built, and from the regions, to which they gave name. He mentions particularly, that there still remained a city called16 [[x]. L. I. p. 77.] Aia upon the Phasis; and the natives retained notions, that AEetes once reigned in that country. He takes notice, that there were several memorials both of Jason and Phrixus in Iberia, as well as in Colchis. 17 [[x]. p. 77.]

In Armenia too, and as far off as Media, and the neighbouring regions, there are, says Strabo, temples still standing, called Jasonea; and all along the coast about Sinope, upon the Pontus Euxinus; and at places in the Propontis, and the Hellespont, as far down as Lemnos, the like traces are to be observed, both of the expedition undertaken by Jason, and of that, which was prior, by Phrixus. There are likewise plain vestiges of Jason in his retreat, as well as of the Colchians, who pursued him, in Crete, and in Italy, and upon the coast of the Adriatic.18 [[x]. Ibid. p. 39.] They are particularly to be seen about the Ceraunian mountains in Epirus: and upon the western coast of Italy in the gulf of Poseidonium, and in the islands of Hetruria. In all these parts the Argonauts have apparently been.

In another place he again takes notice of the great number of temples erected to19 [Ibid. p. 798.] Jason in the east: which were held in high reverence by the barbarous nations. Diodorus Siculus also mentions many tokens of the20 [L. 4. p. 259. [x]. Strabo. L. 5, p. 342. He mentions near Paestum [x]. L. 6. p. 386. Near Circaeum [x]. Lycoph. v. 1274. See the Scholia: also Aristotle [x]. p. 728 and Taciti Annales. L. 6. c. 34.] Argonauts about the island AEthalia, and in the Portus Argous in Hetruria; which latter had its name from the Argo. And he says, many speak of it as a certainty, that the like memorials are to be found upon the Celtic coast; and at Gades in Iberia, and in divers other places.

From these evidences so very numerous, and collected from parts of the world so widely distant, Strabo concludes that the history of Jason must necessarily be authentic. He accordingly speaks of the Argo and Argonauts, and of their perils and peregrinations, as of facts21 [[x]. Strabo. L. I. p. 77.] universally allowed. Yet I am obliged to dissent from him upon his own principles: for I think the evidence, to which he appeals, makes intirely against his opinion. I must repeat what upon a like occasion I have more than once said, that if such a person as Jason had existed, he could never have performed what is attributed to him. The Grecians have taken an ancient history to themselves, to which they had no relation: and as the real purport of it was totally hid from them, they have by their colouring and new modelling what they did not understand, run themselves into a thousand absurdities. The Argo is represented as the first ship built; and the heroes are said to have been in number according to Valerius Flaccus, fifty-one. The author of the Orphic Argonautica makes them of the same22 [He seems to speak of fifty and one. [x]. Argonaut, v. 298. Theocritus styles the Argo [x]. Idyl. 13. V. 74.] number. In Apollonius Rhodius there occur but forty-four: and in Apollodorus they amount to the same. These authors give their names, and subjoin an history of each person: and the highest to which any writer makes them amount, is23 [Natalis Comes makes the number of the Argonauts forty-nine; but in his catalogue he mentions more.] fifty and one. How is it possible for so small a band of men to have achieved, what they are supposed to have performed. For to omit the sleepless dragon, and the bulls breathing fire; how could they penetrate so far inland, and raise so many temples, and found so many cities, as the Grecians have supposed them to have founded? By what means could they arrive at the extreme parts of the earth; or even to the shores of the Adriatic, or the coast of Hetruria? When they landed at Colchis, they are represented so weak in respect to the natives, as to be obliged to make use of art to obtain their purpose. Having by the help of the King's daughter, Medea, stolen the golden fleece, they immediately set sail. But being pursued by AEetes, and the Colchians, who took possession of the pass by the Bosporus, they were forced to seek out another passage for their retreat. And it is worth while to observe the different routs, which they are by writers supposed to have taken: for their distress was great; as the mouth of the Thracian Bosporus was possessed by AEetes; and their return that way precluded. The author of the Orphic Argonautics makes them pass up the Phasis towards the Maeotis: and from thence upwards through the heart of Europe to the Cronian sea, or Baltic: and so on to the British seas, and the Atlantic; and then by Gades, and the Mediterranean home. Timagetus made them proceed northward to the same seas, but by the24 [Scholia in Apollon. L. 4. v. 259.] Ister. According to Timaeus they went upwards to the fountains of the Tanais, through the25 [Diodorus Sic. L. 4. p. 259. Natalis Comes. L. 6. p. 317.] Palus Maeotis: and from thence through Scythia, and Sarmatia, to the Cronian seas: and from thence by the Atlantic home. Scymnus Delius carried them by the same rout. Heliod, and Antimachus, conduct them by the southern ocean to26 [Scholia in Apollon. supra.] Libya; and from thence over land to the Mediterranean. Hecataeus Milesius supposed them to go up the Phasis, and then by turning south over the great continent of Asia to get into the Indian ocean, and so to the27 [Scholia. Ibid.] Nile in Egypt: from whence they came regularly home. Valerius Flaccus copies Apollonius Rhodius, and makes them sail up the Ister, and by an arm of that river to the Eridanus, and from thence to the28 [[x]. Apollon. Rhod. L. 4. v. 627.] Rhone: and after that to Libya, Crete, and other places. Pindar conducts them by the Indian ocean. 29 [Pyth. Ode 4. p. 262.] [x]

Diodorus SIculus brings them back by the same way, as they went out: but herein, that he may make things plausible, he goes contrary to the whole tenor of history. Nor can this be brought about without running into other difficulties, equal to those, which he would avoid. For if the Argonauts were not in the seas spoken of by the authors above; how could they leave those repeated memorials, upon which Strabo builds so much, and of which mention is made by30 [L. 4. p. 259.] Diodorus? The latter writer supposes Hercules to have attended his comrades throughout: which is contradictory to most accounts of this expedition. He moreover tells us, that the Argonauts upon their return landed at Troas; where Hercules made a demand upon Laomedon of some horses, which that king had promised him. Upon a refusal, the Argonauts attack the Trojans, and take their city. Here we find the crew of a little bilander in one day perform what Agamemnon with a thousand ships and fifty thousand men could not effect in ten years. Yet31 [[x]. Diodor. L. I. p. 21. Homer gives Hercules xix ships, when he takes Troy. [x]. Iliad. E. V. 642.] 'Hercules lived but one generation before the Trojan war: and the event of the first capture was so recent, that32 [Anchises is made to day, Satis una superque Vidimus excidia, et capsr superavimus urbi. Virg. AEneid. L. 2. v. 642.] Anchises was supposed to have been witness to it: all which is very strange. For how can we believe, that such a change could have been brought about in so inconsiderable a space, either in respect to the state of Troy, or the polity of Greece?

After many adventures, and Iong wandering in different parts, the Argonauts are supposed to have returned to Iolcus: and the whole is said to have been performed in33 [[x]. Apollodorus. L. I. p. 55.] four months; or as some describe it, in34 [[x]. Scholia in Lycoph. V. 175.] two. The Argo upon this was consecrated to Neptune; and a delineation of it inserted among the asterisms of the heavens. But is it possible for fifty persons, or ten times fifty, to have performed such mighty operations in this term; or indeed at any rate to have performed them? They are said to have built temples, founded cities, and to have passed over vast continents, and through seas unknown; and all this in an open35 [The Argo was styled [x] by Diodorus; and the Scholiast upon Pindar: also by Euripides. It is also called [x]. Orphic Argonaut. V. 1261. and V. 489. [x].] boat, which they dragged over mountains, and often carried for leagues upon their shoulders.

If there were any truth in this history, as applied by the Grecians, there should be found some consistency in their writers. But there is scarce a circumstance, in which they are agreed. Let us only observe the contradictory accounts given of Hercules. According to36 [Herodotus. L. 7. c. 193.] Herodotus he was left behind at their first setting out. Others say, he was left on shore upon the coast of37 [Apollonius Rhodius. L. I. v. 1285. Theocrit. Idyll. 13.] Bithynia. Demaretes and Diodorus maintain that he went to38 [Apollodorus. L. I. p. 45. Diodorus. L. 4. p. 251.] Colchis: and Dionysius Milesius made him the captain in the39 [Apollodoriis. L. I. p. 45.] expedition. In respect to the first setting out of the Argo, most make it pass northward to Lemnos and the Hellespont: but40 [Herodotus. L. 4. c. 179. [x].] Herodotus says, that Jason sailed first towards Delphi, and was carried to the Syrtic sea of Libya; and then pursued his voyage to the Euxine. The aera of the expedition cannot be settled without running into many difficulties, from the genealogy and ages of the persons spoken of. Some make the event41 [Euseb. Chron. Versio Lat. p. 93.] ninety years, some42 [Thrasyllus apud Clement. Alexand. Strom. L. I. p. 401. Petavius 79 years. Rationarii Temp. Pars secunda, p. 109.] seventy-nine, others only forty years before the aera of Troy. The point, in which most seem to be agreed, is, that the expedition was to Colchis: yet even this has been controverted. We find by Strabo, that43 [[x]. Strabo. L. I. p. 80. [x], Strabo, L. I. p. 77.] Scepsius maintained, that AEetes lived far in the east upon the ocean, and that here was the country, to which Jason was sent by Pelias. And for proof of this he appealed to Mimnermus, whose authority Strabo does not like: yet it seems to be upon a par with that of other poets; and all these traditions came originally from poets. Mimnermus mentions, that the rout of Jason was towards the east, and to the coast of the ocean: and he speaks of the city of AEetes as lying in a region, where was the chamber of the Sun, and the dawn of day, at the extremities of the eastern world.

44 [Strabo. L. I. p. 80.] [x]

How can we after this trust to writers upon this subject, who boast of a great exploit being performed, but know not whether it was at Colchis, or the Ganges. They could not tell satisfactorily who built the Argo. Some supposed it to have been made by Argus: others by Minerva.45 [Athenaeus, L. 7. c. 12. p. 296.] Possis of Magnesia mentioned Glaucus, as the architect: by Ptolemy Hephaestion he is said to have been46 [Apud Photium. p. 475.] Hercules. They were equally uncertain about the place, where it was built. Some said, that it was at Pagasae; others at Magnesia; others again at Argos.47 [Scholia in Lycoph. V. 883.] [x]. In short the whole detail is filled with inconsistencies: and this must ever be the case, when a people adopt a history, which they do not understand, and to which they have no pretensions.

I have taken notice, that the mythology, as well as the rites of Greece, was borrowed from Egypt: and that it was founded upon ancient histories, which had been transmitted in hieroglyphical representations. These by length of time became obscure; and the sign was taken for the reality, and accordingly explained. Hence arose the fable about the bull of Europa, the fish of Venus, and Atargatis, the horse of Neptune, the ram of Helle, and the like. In all these is the same history under a different allegory, and emblem. I have moreover taken notice of the wanderings of Rhea, of Isis, of Astarte, of Iona: and lastly of Damater: in which fables is figured the separation of mankind by their families, and their journeying to their places of allotment. At the same time the dispersion of one particular race of men, and their flight over the face of the earth, is principally described. Of this family were the persons, who preserved the chief memorials of the ark in the Gentile world. They Iooked upon it as the nurse of Dionusus, and represented it under different emblems. They called it Demeter, Pyrrha, Selene, Meen, Argo, Argus, Arcas, and Archaius ([x]). And although the last term, as the history is of the highest antiquity, might be applicable to any part of it in the common acceptation; yet it will be found to be industriously introduced, and to have a more immediate43 [It is found continually annexed to the history of Pyrrha, Pelias, Aimonia, and the concomitant circumstances of the Ark, and Deluge. [x]. Schol. in Lycoph. v. 1206. [x]. [x]. Schol. in Apollon. L. I. V. 137.] reference. That it was used for a title is plain from Stephanus Byzantinus, when he mentions the city Archa near mount Libanus. [x]. Upon one of the plates backwards is a representation from Paruta of the Sicilian Tauro-Men with an inscription49 [Parutae Sicilia. p. 104.] [x]. This is remarkable; for it signifies literally Deus Arkitis: and the term [x] above is of the same purport, an Archite. The Grecians, as I have said, by taking the story of the Argo to themselves, have plunged into numberless difficulties. What can be more ridiculous than to see the first constructed ship pursued by a navy, which was prior to it? But we are told, to palliate this absurdity, that the Argo was the first Iong50 [Longa nave Jasonem primum navigasse Philostephanus Auctor est. [Google translate: Philostephanus is the founder of Jason, the first to have sailed on a Iong ship.] Plin. L. 7. c. 56. Herodotus mentions the Argonauts [x]. L. I. c. 2.] ship. If we were to allow this interpretation, it would run us into another difficulty: for Danaus, many generations before, was said to have come to51 [[x]. Scholia in Apollon. L. I. v. 4.] Argos in a long ship: and Minos had a fleet of Iong ships, with which he held the sovereignty of the seas. Of what did the fleet of AEetes consist, with which he pursued the Argonauts, but of Iong ships? otherwise how could he have been supposed to have got before them at the Bosporus, or overtaken them in the Ister? Diodorus indeed omits this part of the history, as he does many other of the principal circumstances, in order to render the whole more consistent. But at this rate we may make any thing of any thing. We should form a resolution, when we are to relate an ancient history, to give it fairly, as it is transmitted to us; and not try to adapt it to our own notions, and alter it without authority.

In the account of the Argo we have undeniably the history of a sacred ship, the first which was ever constructed. This truth the best writers among the Grecians confess; though the merit of the performance they would fain take to themselves. Yet after all their prejudices they continually betray the truth; and shew, that the history was derived to them from Egypt. Accordingly Eratosthenes tells us,52 [[x]. Eratosthenes in [x]. 35.]

that the asterism of the Argo in the heavens was there placed by divine wisdom: for the Argo was the first ship that was ever built: [x], it was moreover built in the most early times, or at the very beginning; and was an oracular vessel. It was the first ship that ventured upon the seas, which before had never been passed: and it was placed in the heavens as a sign, and emblem for those, who were to come after.

Conformably to this Plutarch informs us,53 [[x]. Isis et Osiris. V. i. p. 359.]

that the constellation, which the Greeks called the Argo, was a representation of the sacred ship of Osiris: and that it was out of reverence placed in the heavens.