Chapter 6: Sun Worship

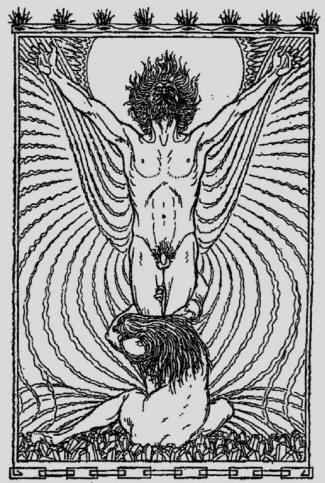

If one honors God, the sun or the fire, then one honors one's own vital force, the libido.

-- C. G. Jung, Psychology of the Unconscious, 1911

Not even the most recent scientific discoveries ... which teach us how we live, and move, and have our being in the sun, how we bum it, how we breathe it, how we feed on it -- give us any idea of what this source of light and life, this silent traveller, this majestic ruler, this departing friend or dying hero, in his daily or yearly course, was to the awakening consciousness of mankind. People wonder why so much of the old mythology, the daily talk, of the Aryans, was solar: -- what else could it have been?

-- Friedrich Max Muller, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion, 1878

What I am now about to say I consider to be of the greatest importance for all things "that breathe and move upon the earth" ... but above all others it is of importance to myself. For I am a follower of King Helios. And of this fact I possess within me, known to myself alone, proofs more certain than I can give. But this, at least, I am permitted to say without sacrilege, that from my childhood an extraordinary longing for the rays of the god penetrated deep into my soul.

-- Julian, Emperor of Rome, "Hymn to King Helios," 362 C.E.

Who can possibly understand the true source of the archaic, rejuvenating energies that pulsed through C. G. Jung in the years following his encounters with Otto Gross and Sabina Spielrein? Not only did sexual energy surge through him with a power that frightened him, but terrifying, decidedly Wagnerian visions of Teutonic figures such as Wotan and Siegfried and of the cosmic dramas of Greek mythology dominated both his waking fantasies and his nocturnal dreams. He had been a man who prided himself on the rational control of his thoughts, of his ability to maintain composure in the face of psychosis, a man who devalued a spontaneous fantasy life as weak, sick, repulsive. But soon he found that he could not regulate the swirling modern chaos in his own psyche.

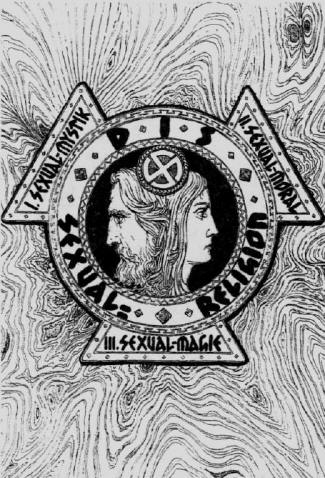

Between September 1909, when it was clear that the transformational process had begun, and September 1912, when he published his confirmation of his loss of faith in Freud and in the Judeo-Christian god, Jung's attitude toward the unconscious mind changed profoundly. At first believing the unconscious mind to be an entirely personal and individual warehouse of memories, he came to see it as the source of ancestral wishes and tendencies -- and even experiences -- that were inherited biologically through a type of vitalistic mechanism, a generalized life-force called the libido. By September 1912 he made it clear to Freud and to his own circle in Zurich that this powerful energy of life was not only the sex drive, as Freud had maintained, but should be viewed as a more generalized force of nature whose currents carried ancestral spiritual longings through biological channels.

During these three years, Jung developed the idea that the unconscious mind was the result of a long, phylogenetic, evolutionary process. Just as the human body is a living museum of evolutionary history, so too is the human psyche. And since the most potent ideas of human concern are religious ones, we should discover the spiritual symbols of our ancestors deep within the unconscious mind of each individual. That is, looking at the evolutionary development of the human species, the most recent, and therefore most powerful, influences on present human experience would be racial or tribal ones. In Jung's new view, religious needs were biologically based. The peoples of pagan antiquity, closer to our prehistoric ancestors, celebrated their sexuality in their spirituality and were therefore less plagued by neuroses and psychoses than modern Europeans. Jung forged these insights into the theory that a life could only be meaningful if one's religious beliefs and sexual practices resonated with those of one's racial ancestors.

Everything in the world is in a state of evolution, human consciousness included. Man has not always had the consciousness he now possesses; when we go back to the times of our earliest ancestors, we find a consciousness of a very different kind. At the present time man in his waking-life perceives external things through the agency of his senses and forms ideas about them. These ideas about the external world work on his blood. Everything, therefore, of which he has been the recipient as the result of sense-experience, lives and is active in his blood; his memory is stored with these experiences of his senses. Yet, on the other hand, the man of to-day is no longer conscious of what he possesses in his inward bodily life by inheritance from his ancestors. He knows naught concerning the forms of his inner organs; but in earlier times this was otherwise. There then lived within the blood not only what the senses had received from the external world, but also that which is contained within the bodily form; and as that bodily form was inherited from his ancestors, man sensed their life within himself.

If we think of a heightened form of this consciousness, we shall have some idea of how this was also expressed in a corresponding form of memory. A person experiencing no more than what he perceives by his senses, remembers no more than the events connected with those outward sense-experiences. He can only be aware of such things as he may have experienced in this way since his childhood. But with prehistoric man the case was different. Such a man sensed what was within him, and as this inner experience was the result of heredity, he passed through the experiences of his ancestors by means of his inner faculty. He remembered not only his own childhood, but also the experiences of his ancestors. This life of his ancestors was, in fact, ever present in the pictures which his blood received, for, incredible as it may seem to the materialistic ideas of the present day, there was at one time a form of consciousness by means of which men considered not only their own sense-perceptions as their own experiences, but also the experiences of their forefathers. In those times, when they said, "I have experienced such and such a thing," they alluded not only to what had happened to themselves personally, but also to the experiences of their ancestors, for they could remember them.

This earlier consciousness was, it is true, of a very dim kind, very hazy as compared to man's waking consciousness at the present day. It partook more of the nature of a vivid dream, but, on the other hand, it embraced far more than does our present consciousness. The son felt himself connected with his father and his grandfather as one "I," because he felt their experiences as if they were his own. And because man was possessed of this consciousness, because he lived not only in his own personal world, but because within him there dwelt also the consciousness of preceding generations, in naming himself he included in that name all belonging to his ancestral line: father, son, grandson, etc., designated by one name that which was common to them all, that which passed through them all; in short, a person felt himself to be merely a member of an entire line of descendants. This sensation was a true and actual one.

We must now enquire how it was that this form of consciousness was changed. It came about through a cause well known to occult history. If you go back into the past, you will find that there is one particular moment which stands out in the history of each nation. It is the moment at which a people enters on a new phase of civilisation, the moment when it ceases to have old traditions, when it ceases to possess its ancient wisdom, the wisdom which was handed down through generations by means of the blood. The nation possesses, nevertheless, a consciousness of it, and this is expressed in its legends.

In earlier times tribes held aloof from each other, and the individual members of families intermarried. You will find this to have been the case with all races and with all peoples; and it was an important moment for humanity when this principle was broken through, when foreign blood was introduced, and when marriage between relations was replaced by marriage with strangers, when endogamy gave place to exogamy. Endogamy preserves the blood of the generation; it permits of the same blood flowing in the separate members as flows for generations through the entire tribe or the entire nation. Exogamy inoculates man with new blood, and this breaking-down of the tribal principle, this mixing of blood, which sooner or later takes place among all peoples, signifies the birth of the external understanding, the birth of intellect.

The important thing to bear in mind here is, that in olden times there was a hazy clairvoyance, from which the myths and legends originated. This clairvoyance could exist in the nearly-related blood, just as our present-day consciousness comes about owing to the mingling of blood. The birth of logical thought, the birth of the intellect, was simultaneous with the advent of exogamy. Surprising as this may seem, it is nevertheless true. It is a fact which will be substantiated more and more by external investigation; indeed, the initial steps along this line have already been taken.

But this mingling of blood which comes about through exogamy is also that which at the same time obliterates the clairvoyance of earlier days, in order that humanity may evolve to a higher stage of development; and just as the person who has passed through the stages of occult development regains this clairvoyance, and transmutes it into a new form, so has our waking consciousness of the present day been evolved out of that dim and hazy clairvoyance which obtained in times of old.

At the present time everything in a man's environment is impressed upon his blood; hence the environment fashions the inner man in accordance with the outer world. In the case of primitive man it was that which was contained within the body that was more fully expressed in the blood. In those early times the recollection of ancestral experiences was inherited, and, along with this, good or evil tendencies. In the blood of the descendants were to be traced the effects of the ancestors' tendencies. But, when the blood was mixed through exogamy, this close connection with ancestors was severed, and man began to live his own personal life. He began to regulate his moral tendencies according to what he experienced in his own personal life. Thus, in an unmixed blood is expressed the power of the ancestral life, and in a mixed blood the power of personal experience.

-- The Occult Significance of Blood, by Rudolf Steiner

Polygamy unblocked the rays of this inner source of light and heat that had been eclipsed by centuries of monotheism and the monogamy crushingly demanded by Judeo-Christianity. Otto Gross had taught him that, but Gross fused this knowledge of the morally corrosive effect of polygamy with efforts to bring about an associated change in political consciousness and thereby incite revolution and anarchy. What Jung desired instead were additional psychotherapeutic methods to effect spiritual rebirth. He sought potent new symbols of transformation to bring about changes of consciousness in large numbers of people. He became increasingly certain of his own destiny as the man who would deliver such redemption to humanity but was uncertain of the means of achieving it. After a dream pointed the way, he knew the secret he was looking for was buried in the accounts of pagan regeneration.

Once Jung charged down this intellectual path there was no stopping him. To be sure, a multitude of others had preceded him on this quest. In German Europe at that time legions of scientists and artists, bohemians and bourgeoisie, were fervently seeking much the same thing. And, when we listen carefully to their voices through the cacophony of historical events that took shape beginning in 1933, we can hear the faint singing of their hymns to the sun.

"I often feel I am wandering alone through a strange country"

It all began with a dream aboard the ship that carried Jung and Freud back to Europe after they attended the Clark University Conference in September 1909. Jung found himself descending layer by layer -- spatially and temporally -- into the foundations of a large old house. As the story is told in MDR, Jung left a "rococo style salon" on the top floor for a fifteenth- or sixteenth-century dwelling on the ground floor. [1] He then descended a stone stairway that led to a room from "Roman times," and then farther down to a "low cave cut into the rock" where, at the lowest levels, he found the remnants of a primitive culture: pottery, scattered human bones, and "two human skulls."

In MDR, Jung credits this dream for giving him his first idea of a collective unconscious. In a 1925 lecture in which he gave a slightly different version of it, he told his audience that he had "a strongly impersonal feeling about the dream," indicating, at least to him, that it was less a product of his own personal unconscious than something akin to a message from the great beyond. [2] Later in life he told E. A. Bennett something different that calls into question the mystical nature of Jung's interpretation. In Bennett's account, Jung associates the supposedly "impersonal" material from the collective unconscious with some very personal thoughts: "When he reflected on it," wrote Bennett, "later the house had some associations in his mind with his uncle's very old house in Basel which was built in the old moat of the town and had two cellars; the lower one was very dark and like a cave." [3] In any event, the dream did stir something in Jung that put him on a different track entirely.

Immediately after his return home, Jung began to visit archeological sites so that he could observe ongoing excavations. He began an intensive study of mythology and Hellenistic spiritual practices in the classical scholarship of his day. "Archeology or rather mythology has got me in its grip," Jung wrote to Freud on October 14, 1909. [4] This became a familiar theme in their correspondence over the next two and a half years.

As a boy, Jung had wanted to become a classical philologist or an archeologist. His newfound project reawakened these childhood fantasies. "All my delight in archeology (buried for years) has sprung into life again," he told Freud. [5] Soon, however, his study of mythology took on an almost obsessive quality, and mythological figures began to intrude in his daily fantasies and dreams. On February 20, 1910, he told Freud, "All sorts of things are cooking in me, mythology in particular." [6] By April 17, he was afraid of the effect that his researches might have been having on his mental state: "At present I am pursuing my mythological dreams with almost autoerotic pleasure, dropping only meager hints to my friends .... I often feel I am wandering alone through a strange country, seeing wonderful things that no one else has seen before and no one needs to see .... I don't yet know what will come of it. I must just let myself be carried along, trusting to God that in the end I shall make a landfall somewhere." [7] By February 15, 1912, Jung was in a panic. "I am having grisly fights with the hydra of mythological fantasy and not all its heads are cut off yet. Sometimes I feel like calling for help when I am too hard-pressed by the welter of material. So far I have suppressed the urge." [8]

Jung's efforts were not in vain. Even as early as the end of November 1909 it was clear that he had developed a new theory for psychoanalysis that would have profound racial implications for its future.

The phylogenetic unconscious

In the spring of 1909, Jung had resigned from his post at the Burgholzli and saw patients privately in his consulting room at his new home in Kusnacht, approximately seven miles southeast of Zurich. Although not a move of great distance spatially, it was for Jung, psychologically. From his new home on Lake Zurich, in a letter to Sigmund Freud, Jung outlined for the very first time the contours of his new racial theory of the unconscious:

I feel more and more that a thorough understanding of the psyche (if possible at all) will only come through history or with its help. Just as an understanding of anatomy and ontogenesis is possible only on the basis of phylogenesis and comparative anatomy. For this reason, antiquity now appears to me in a new and significant light. What we now find in the individual psyche -- in compressed, stunted, or one-sidedly differentiated form -- may be seen spread out in all its fullness in times past. Happy is the man who can read these signs! The trouble is that our philology has been as hopelessly inept as our psychology. Each has failed the other. [9]

By Christmas, Jung had employed the assistance of one of his young psychiatrists at the Burgholzli, Johann Jakob Honegger. As he told Freud (December 25, 1909), he entrusted to Honegger everything that he knew "so that something good may come of it." By now Jung was even more convinced that he was on the verge of a breakthrough, for he was having "the most marvelous visions, glimpses of far-ranging interconnections which I am at present incapable of grasping." Again he confirmed to Freud the new direction of his thinking: "It has become quite clear to me that we shall not solve the ultimate secrets of neurosis and psychosis without mythology and the history of civilization, for embryology goes hand in hand with comparative anatomy." [10]

One of Jung's strengths -- and indeed his "genius" -- was his remarkable ability to synthesize highly complex and seemingly unrelated fields of inquiry. Early in his career, Jung attempted to use the lessons learned from his experimental researches using the word-association test to explain the phenomenon of hysterical "repressions" in psychoanalysis and the alternate personalities of "spirits" that arose during mediumistic trances. His theory that the normal human mind was made up of unconscious complexes -- semiautonomous clusters of images, thoughts, and feelings organized around a specific motif or thematic core -- was his overarching explanation for these phenomena. Later, when he first consciously identified himself with Freud and the psychoanalytic movement, he tried to integrate that complex theory with psychoanalysis in a wide range of publications, his most famous being a small book on the psychology of dementia praecox. [11]

By November 1909, Jung's clinical experience had stimulated him to cast his intellectual net even wider. What Jung already saw as his intellectual "project" was nothing less than a grand synthesis of psychoanalysis with evolutionary biology, archeology, and comparative philology. If Jung found a way to integrate psychoanalysis with these esteemed sciences, so revered as the finest of German scientific contributions to the world in the late nineteenth century, it would be a coup of major proportions for the psychoanalytic movement. It would confirm Freud and Jung's claims that psychoanalysis was a science that could spur the development of insights in other disciplines. With its analysis of word associations as a method of recovering the past of an individual, the techniques of psychoanalysis perhaps most resemble those of comparative philology, which attempts to recover the original cultural and linguistic forms. And, like psychoanalysis, philologists, too, are interested in how the laws of language seem to be related -- or are identical -- with the laws governing the operation of the mind. It is no wonder that Freud encouraged Jung along these paths, but it was a project that would ultimately rend psychoanalysis -- at least in Switzerland -- along ethnic and racial lines.

Jung wasted no time. He gave his psychiatric assistants extensive reading assignments from the works of classicists, archeologists and philologists on the mythological systems of pagan antiquity. Two of them -- Spielrein and Jan Nelken -- published extensively documented articles making use of their knowledge of mythology to analyze the hallucinations and delusions of patients with dementia praecox. Honegger was the first to present his findings in public at a conference in 1910. A fourth disciple from an asylum outside Zurich, Carl Schneiter, entered the picture a bit later and published a similar vindication of Jung's views in 1914. [12]

Jung assigned his assistants to go into the back wards of their respective asylums and collect mythological material from psychotic patients, almost as if each new hallucination or delusion was an exotic new species of flora or fauna to analyze and catalog. Until Jung assigned them books on mythology, it is a safe bet that these young physicians had little formal training in mythology or archeology. Armed with their new knowledge, they entered the wards and found exactly what Jung told them to look for: ancient pagan gods in the unconscious of their patients.

And the ones they found most often in the most "regressed" psychotic patients -- just as Jung said they would -- were various pre-Christian solar deities: sun gods.

Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido

Jung's psychiatric assistants funneled new clinical material to him that confirmed the presence of pre-Christian mythological motifs in psychotic patients. Jung immediately put this wealth of evidence into his magnum opus, which would put him and psychoanalysis on the map. First published as two long articles in a psychoanalytic journal in 1911 and 1912, Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (Transformations and symbols of the libido) appeared as one book in the latter year. [13]

It is a strange book. It was judged so in its day and it remains so now. Without the proper keys to unlock the book's argument, the reader is hopelessly lost. However, to Jung's disciples -- and to the mystically minded from all quarters of bohemia -- it was received as a stunning revelation, a celebration of neopagan life.

Jung's book has at least two separate agendas and can be read in at least two ways: first, as an attempt to syncretize the methodology of psychoanalysis with those of the esteemed sciences of comparative philology, comparative mythology, and evolutionary biology; second, as a blending of different philosophies of regeneration or rebirth. Psychoanalysis thus became not only a science but also a path of cultural and individual revitalization -- which, indeed, it had become for Jung by the time he started the book in 1910. [14]

The writing of this book mirrored a transformation process in Jung himself, the result of which was the loss of his Christian identity and the development of a compensating new vital experience of God. Jung's starting point was a small article published by an unusual American woman, Miss Frank Miller, which contained a series of poetic musings and accounts of her personal visions. [15] She had all the gifts of a spiritualist medium, and she knew it. Many of her visions and experiences could even be interpreted as evidence of reincarnation or of a spirit world. However, after studying in Geneva for a time with Theodore Flournoy, she decided to write an article demonstrating that all of the material arising spontaneously from her "creative imagination" could be traced to things she had previously seen, read, or heard. In effect, she was writing to support Flournoy's thesis that all creative productions were the result of new combinations of previously memorized material whose source had long been forgotten -- in other words, cryptomnesia.

Jung took Frank Miller's visions and poetry and argued just the opposite: that these could not possibly have been the creation of new combinations of hidden memories but instead were evidence of a phylogenetic layer of the unconscious mind that could produce pre-Christian symbols from pagan antiquity. From the time the first part of Wandlungen appeared in a journal in 1911, Jung never again entertained the possibility that mythological content in his patients' dreams or psychotic symptoms were anything but evidence of a phylogenetic or "collective" unconscious layer of the human mind.

Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

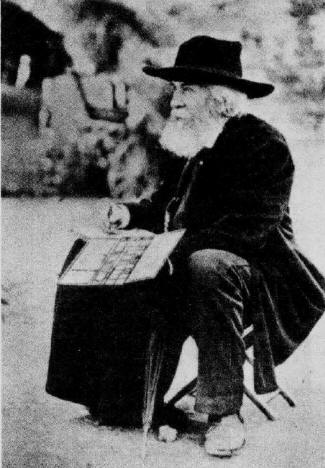

The basic theory of Wandlungen is based on the famous formula "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny," popularized at the end of the nineteenth century by the German zoologist and evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel, who almost single-handedly introduced Darwinism to the German public. Haeckel actively promoted the notion that evolution was progressive and purposeful. His biological theories were a blend of Darwinism, Lamarckianism, and the old German Romantic biology of Goethe. Haeckel was the first to argue -- as Jung would analogously about psychoanalysis -- that biology was first and foremost a historical science, involving the historical (not experimental) methodologies of embryology, paleontology, and especially phylogeny.

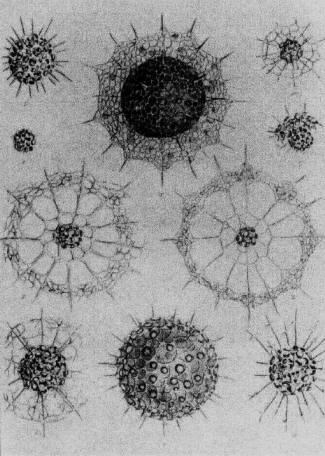

Jung's favorite areas of study in medical school were comparative morphology and evolutionary theory -- areas that Haeckel dominated. Jung's fascination with Haeckel predates medical school, however. In MDR he tells of a dream in which he found a great circular pool in a forest clearing. In this pool, "half immersed in the water lay the strangest and most wonderful creature: a round animal, shimmering in opalescent hues, and consisting of innumerable little cells, or of organs shaped like tentacles. It was a giant radiolarian, measuring about three feet across." [16] To Jung, this dream was a prophetic message from beyond, presaging a destiny as a natural scientist and physician. Haeckel's exquisite color illustrations of radiolaria had appeared in popular science books and magazines, and we know that Jung read such magazines as a teenager. He could have picked up his knowledge of radiolaria only from Haeckel. [17]

What is so unusual about this dream, however, is its incongruity with reality, never explained in MDR or in any of the scores of Jungian retellings of this magical story. A radiolarian is a tiny sea organism enclosed in an intricate spherical -- and beautiful -- exoskeleton. But it is a microscopic organism; one cannot see a radiolarian clearly with the naked eye. There are no three-foot long radiolaria as magnified in the sacred monster of Jung's dream. The inflation of a simple natural phenomenon into a giant, otherworldly spectacle is a signature stroke of Jung. His application of Haeckel' s "biogenetic law" to stages of cultural evolution and to the evolution of human consciousness is just one more example.

Haeckel's biogenetic law -- "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny" -- was derived from his historical researches in biology, and profoundly influenced not only evolutionary biology but also theories of the mind in psychology, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis. The notion that the stages of individual development (ontogeny) could be shown to replicate, in order, the stages of the development of the human race from lower forms of life (phylogeny) was a compelling theory. Both Jung and Freud adopted such thinking in their own work, though they rarely referred to Haeckel.

Jung believed that changes in the libido over time could be discerned through the study of ancient religions and cultures. If he could identify certain stages of transformations of the libido over time that corresponded with the transformations of libido in a developing individual, psychoanalysis could rightly claim it had unlocked the secrets of life and of history. Jung knew he was the man to do it.

Throughout the layers of mythological references in Wandlungen, Jung eventually blends Haeckel's ideas with those of Freud and Bachofen into a new model of the human mind: Freud's stages of psychosexual development (the infantile period of polymorphous perversity; the preoedipal, incestuous period of strong attachment to the mother; the phallic stage; and then the genital stage) all seem to correspond with the descriptions of Bachofen's stages of cultural evolution (hetairism; matriarchy; the transitional Dionysian period; and then patriarchy). Haeckel's law provides the unifying biological and evolutionary key.

Having outlined the basic skeleton, Jung needed to provide evidence of symbolic content from contemporary patients and from the cultures of the past that would fit each of these stages.