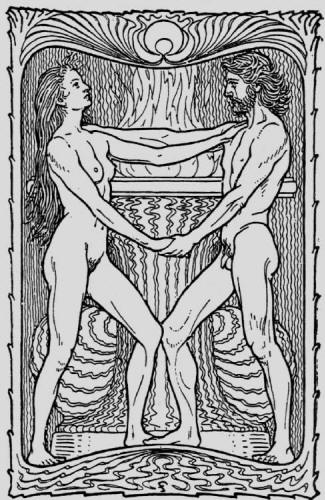

PART ONE: Genesis Fidus, "Liebe" ("Love"), 1916Chapter 1: The Inner Fatherland

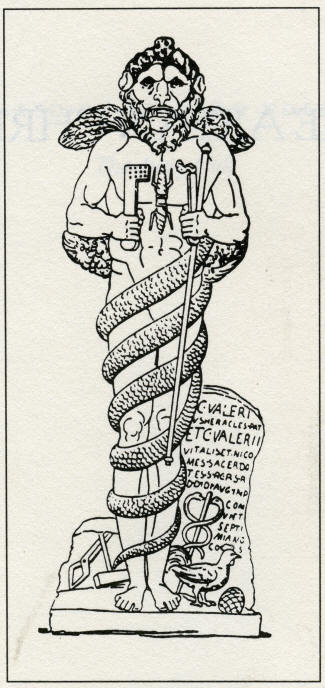

Fidus, "Liebe" ("Love"), 1916Chapter 1: The Inner FatherlandAlong the banks of upper Lake Zurich, on a silent patch of land in Bollingen, the stone structure known as Jung's Turm (Tower) remains a site of pilgrimage. Jung began building the small, primitive refuge in 1923 as a round container for his solitude. Later, with additions, it became a tower and a sacred space where he could paint his visions on the walls and preserve them in carved stone. It also became a sexual space, a pagan sin altar where, removed from his wife and family in Kusnacht and his disciples in Zurich, he could enjoy his intimate companion, Toni Wolff, with orgiastic abandon. An unsettling mural that covers the entire wall of the bedroom depicts his spirit guide, Philemon, the transpersonal entity whom Jung met in visions during the First World War. Philemon is an interloper from the Hellenistic period, an old man with a long white beard and the wings of a kingfisher. [1] It is from his discussions with Philemon, or so the story goes in MDR, that Jung received his most profound insights about the nature of the human psyche. Jung's most famous ideas -- the collective unconscious, which he first described -in print in 1916, and the archetypes (its "gods"), which were added shortly thereafter -- would not have been possible without guidance from Philemon. [2] It is from this Gnostic-Mithraic guru, who lives in a timeless space that Jung called the Land of the Dead, that Jung received instruction in "the Law," the esoteric key to the secrets of the ages. Jung inscribed these lessons in his "Red Book."

Privileged visitors who are invited by members of the Jung family are allowed to see this icon of Philemon. Another painting, in another part of the Tower, is revealed only to intimates. Usually concealed, perhaps to protect the eyes of the uninitiated from witnessing the sacred mysteries it portrays, is the image of a thin crescent ship, like those that carry the dead in Egyptian iconography, with male and female figures facing each other. In the center of Jung's vision is a large, reddish solar disk that brings to mind the frightful passage of souls to the underworld in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Outside in the courtyard, adjacent to the Tower, stand three stone tablets upon which, as Jung tells it in MDR, "I chiseled the names of my paternal ancestors." [3] The imaginal world of the ancestors, Jung's inner fatherland, was a living presence in Jung's everyday experience. Ahnenerbe, "ancestral inheritance," is the ground of all subjective experience within every individual, according to Jung. We find this idea at the epicenter of his worldview from a very early age, in an alien part of his child-self that he called his "number two personality" -- an elderly gentleman of the eighteenth century-allowing him to imagine he was "living in two ages simultaneously, and being two different persons." [4] He is an individual, yet a second heart beats in his breast, a sacred heart that squeezes the lifeblood of the ancestors through his veins. This, too, has origins in the nostalgic culture of his day, an era when heredity and Kultur and the landscape were merged with one's soul in the timeless and deeply resonant concept of Volk (a much fuller term than our poor derivative "folk"; the German spelling will be kept throughout to maintain this distinction).

"When I was working on the stone tablets," Jung confided, "I became aware of the fateful links between me and my ancestors .... It often seems as if there were an impersonal karma within a family, which is passed from parents to children. It has always seemed to me that I had to answer questions which fate had posed to my forefathers, and which had not yet been answered, or as if I had to complete, or perhaps continue, things which previous ages had left unfinished." [5]

What questions did Jung's paternal ancestors leave unanswered? What did Jung feel compelled to complete or to continue? What was the family karma that bound Jung to a specific fate? These questions already contain the seeds of their answers. What we must listen for here are the assumptions behind the queries, the brand of reality that would allow the possibility of such statements or questions in the first place. It is an arcane reality that Jung was destined to keep alive for millions in the twentieth century.

1817: The Thing at the WartburgWhat no one could forget were the bells. Joyously ringing their welcome to the young men who had come from afar, the bells of Eisenach would be forever etched in their memories. [6] Having gathered just outside the red-tiled buildings of this medieval German town, the young men lit torches and began their solemn procession up to the castle, yellow and red autumn leaves blanketing their path. Some of the young men referred to this congregation at the Wartburg castle as a Thing -- what the ancient Germans called their annual tribal gatherings. Some of the young men were in ancient German dress, but most wore the Trachten, or traditional folk dress, of their native regions. They were urged to do so by the event's organizers, one of whom was Friedrich

Ludwig Jahn, the famous "Turnvater Jahn," best remembered for founding gymnastics societies (Turnvereinen). There was no Germany in 1817, only several dozen principalities united by language, culture, and their common history of being recently overrun by Napoleon's armies. Jahn's gymnastics societies were designed to kindle the sparks of German nationalism in a defeated, fragmented, and often sleepy population. (Many of the foreign travelers through these lands in the nineteenth century described the Germans as rather indifferent, dreamy folk, all too glad to share their bread, wurst, and beer -- not as seething tribes of warriors.)

Many of the young men marching with torches to the Wartburg castle that day were members of these proud gymnastics societies. The rest belonged to student fraternities, some of them secret known as Burschenschaften. Most were from the university in Jena. These student fraternities had only just come into being, but they would play an important role in German cultural life in the nineteenth century. [7] Some of them were also affiliated with an older secret society, the Freemasons, for whom the rose and the cross were blended into a meaningful occult symbol. Some of the participants at the Wartburg festival wore cloth bands around their torsos in the colors that comprise the flag of today's Germany -- black, red, and gold.

It was no coincidence that these rituals of nascent German national fervor played out in the shadow of the mighty Wartburg fortress on an October night. It was here that Martin Luther gave Jesus a German accent. Luther's translation of the New Testament into German catalyzed nationalist sentiment and revolutionized the German world of letters. Heinrich Heine captures so many of the contradictions in the German soul in his often quoted description of Luther as "not merely the greatest but also the most German man in our history, so that in his character all the virtues and failings of the Germans were united in the most magnificent way." Luther was "the tongue as well as the sword of his age ... a cold scholastic word-cobbler and an inspired, God-drunk prophet who, when he had worked himself almost to death over his laborious and dogmatic distinctions, in the evening reached for his flute and, gazing at the stars, melted in melody and reverence." [8] For many of the young men, the commanding walls of the Wartburg fortress rose above them like the brooding, corpulent specter of Martin Luther himself.

In October of 1517 a defiant Martin Luther hammered his theses of protestation to a church door. October also was celebrated as the anniversary of the defeat of Napoleon at Leipzig in 1813. The feeling of being German swelled whenever these victories of the Volk were recounted.

"Feelings" of being German were all that one could have, for "Germany" was a word for an ideal, not a reality. German-speaking peoples lived in a loose confederation of dozens of autonomous states of varying sizes and significance bound only by a weakly ruled political entity called the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. They shared no common currency or legal system, and travel and commerce between many of them was a gauntlet of complex taxes, customs fees, and unanticipated local restrictions on personal freedoms.

At the foot of the Wartburg, the men built a huge, blazing bonfire and other pillars of fire that could be seen by the people of Eisenach. Encircling the central fire, with an excitement driven by a sense of the sacred and the dangerous, the men sang the traditional hymn "Eine Feste Burg" ("A Mighty Fortress Is Our God"). One of the leaders then offered a few inspirational remarks about justice and invoked the important symbol of the German forest of oaks. The mighty oak was sacred to the ancient Teutons and indeed was the "cross" upon which Wotan (Odin) underwent his revelatory self-sacrifice. Nostalgic references to it recur throughout more than a century of German spiritual longing.

More songs were sung and a patriotic sermon was delivered. Then, before a final hymn to end the formal segment of their ritual, the young men joined hands around the fire and took a collective oath of allegiance to one another and to their group (Bund). They also pledged to preserve the purity of the Volk. Before the Wartburgfest concluded, for the first time in recorded German history "un-German books" were denounced and burned in the great central fire.

Karl Gustav Jung -- the grandfather of Carl Gustav Jung -- considered his participation in the Wartburgfest one of the purest and most meaningful experiences of his life. He was twenty-three. He carefully preserved his black, red, and gold wrap from his days of student activism, and it became one of his grandson's most cherished possessions.

The problem for

Karl Follen was to find a new intellectual and political environment in Switzerland, since he had lost his school teaching post. Once again, he managed to come upon just the right place: the University of Basel. It had been an important intellectual center in the sixteenth century, and then had fallen into decay. In 1817, however, the university was refounded and reorganized. Professors' chairs were being filled with German exile intellectuals, many of whom the Swiss authorities could find throughout the country. What was being set up at Basel was an international center of liberal and even radical ideas, a place from which the Swiss students would profit because of the excellence of the new German scholars, and from which the liberal scholars would gain because there they would be allowed to freely discuss their political and religious ideas, and make plans for the future of Germany.

Follen was appointed as a lecturer on natural, civil, and ecclesiastical law, and found many of his former friends already installed at Basel. The exact title of his designated academic field (venia legendi), awarded to him in November of 1821, was "psychology and logic." Follen taught as a member of the philosophical faculty. His lectures were on the Pandects, philosophy of law, public law, and canon law. In January of 1824, it was suggested by the university administration that he should be made a full professor because of the "thoroughness of his knowledge and his constant work for the best of the university." He remained at the university until the summer semester of 1824, during which he was on sabbatical from his teaching responsibilities. The social surroundings at Basel were as agreeable as the university scene. Follen became engaged to marry Anna de Lassaulx, the daughter of a local professor (she later refused to follow him to America). While the city council was quite conservative and dominated by a group of older local notables, there was also a set of younger, more liberal, and modern-minded intellectuals around the city with whom Follen and others like him could come into contact, for instance through a new "literary society" founded in the fall of 1821. Most important for Follen, however, was the opportunity to once again gather with many of his longtime political associates from Germany, many of them now refugees at Basel University.

The most prominent of the German exiles, to be sure, was the new professor of theology. Wilhelm Leberecht de Wette, author of the open letter of sympathy to Carl Sand's mother, had now found a new home in Basel, and began editing a university scholarly journal together with Karl Follen. De Wette had been a student and Privatdozent in Jena from 1799 to 1807, and then professor of theology at Heidelberg. In 1810 he accepted a chair at Berlin, from which he was removed by the government in 1819. After a stay in Weimar he arrived in Basel in 1822, staying there until his death in 1849. He was known throughout the scholarly world not only for his important research in Protestant theology but also for his unambiguously liberal opinions. He was an open sympathizer of the Burschenschaft and one of the closest friends of the Jena philosopher Jakob Friedrich Fries.

Another German scholar at Basel was De Wett'es stepson Karl Beck, who would eventually accompany Follen on his journey to America three years later. In addition, there was the legal scholar Wilhelm Snell from Hesse, who had worked with Follen in the Hesse German reading society and the Blacks, and another radical, a medical doctor named Carl Gustav Jung. The Burscheschaft leader Wilhelm Wesselhoft, whose brother Robert had been a key speaker at the Wartburg festival, was also present on the university faculty. De Wette tried in 1822 to persuade his friend Jakob Friedrich Fries, who was being investigated at Jena and would soon lose his professorship there, to move to Basel. Fries would not himself come, but he suggested someone else to be hired in his place. This was Karl Seebold, one of Follen's closest friends and a very early member of the Giessen Blacks. Only a few years later Wilhelm Snell's brother Ludwig was also able to join the philosophical faculty. He was given the venia legendi for philosophy. It is astounding how these radicals, who had been working together for over ten years, were able to gather once more in the same town; many of the original Giessen Blacks were together again at Basel.

-- Charles Follen's Search for Nationality and Freedom: Germany and America 1796-1840, by Edmund Spevack

"Where Jung was, there was life and movement, passion and joy"Karl Gustav Jung was born in Mannheim in 1794 to a physician, Franz Ignaz Jung, and his wife, Maria Josepha, rumored by later generations to have submitted, like Europa, to a most remarkable infidelity. Little is known about Karl's childhood. The Jungs were Roman Catholics from Mainz and distinguished by their heritage of German physicians and jurists. In a diary Karl kept in his later years, we know that his father had always remained something of a stranger to him and that his mother was inclined toward bouts with depression. (A similar parental constellation is described by Karl's grandson in the early chapters of MDR.) The Jung family cannot be traced prior to its residence in Mainz, for the public archives were burned in 1688 during the French occupation.

Franz Ignaz Jung served in a lazaretto during the Napoleonic wars. His brother, Sigismund von Jung, was a high-ranking Bavarian official who was married to the youngest sister of perhaps the most famous religious and nationalist figure in Germany at that time, Friedrich Schleiermacher.In a drawing of Karl dated February 1821, we see a young man with longish curls, seductive, heavy-lidded eyes, and a truly aquiline nose; he resembles a Teutonic Byron. [9] In his youth he was, simultaneously, political activist, poet, playwright, and physician. In his lifetime he would give thirteen children to three wives. Energetic, extraverted, full of passion for living, his boundless energy thrilled and, at times, crushed others. At his burial in 1864, his friend the chemist Schoenbrun said, "Where Jung was, there was life and movement, passion and joy." [10] At the 1875 opening of the Vesalianum, the anatomical institute at the University of Basel, the elderly Wilhelm His remembered Jung's "continual optimism and unbending high-spirits, which were not broken by difficult family sorrows." These sorrows were the early deaths of most of Jung's children, as well as of his first two wives. One of the few progeny that survived into adulthood was his last child, the lucky thirteenth, Johann Paul Achilles Jung, who would live to sire a son, Carl Gustav, in 1875 and a daughter, Gertrud, in 1884.

Like his father and grandson, Karl Gustav Jung was a physician. He was trained at Heidelberg, that famous university town, an important center of alchemy and a symbol in Rosicrucian lore. He earned his medical degree in 1816, then moved to Berlin to practice as a surgical assistant to an ophthalmologist. Berlin changed him forever.

Place, landscape, soil -- to understand the imaginal world of Jung it is important to identify these nodal spaces where meaning condenses, the earthen crossroads upon which history rains. Such a place was

the home of the Berlin bookseller and publisher Georg Andreas Reimer, an intimate friend of Schleiermacher. Reimer served as the host of the Reading Society, a patriotic club that met in his home. Ernst Moritz Arndt, one of the founding fathers of the nationalist Volkish movement (Volkstumbewegung) in Germany, befriended Schleiermacher here. To avoid prosecution for anti-French activity in the occupied German heartland, Arndt fled to Berlin, the capital of Prussia, and lived in Reimer's home from 1809 to 1810. [11] In 1816 and 1817, so did Karl Gustav Jung.

At Reimer's, Jung found himself in one of the central incubators of German Romanticism and nationalism. He came into contact with a steady flow of ideas from determined men- -- ome of them political fugitives -- who were convinced of the idea of a Volksgeist, the unique characteristics or genius of the German people as a single nation, determined by language, climate, soil or landscape, certain economic factors, and, of course, race. These ideas found form in the essays of J. G. Herder, Arndt, Jahn, and the sermons of Schleiermacher. Here Jung met the Schlegel brothers -- Friedrich and August Wilhelm -- and Ludwig Tieck, all noted writers and founders of the Romantic movement. Jung underwent a transformation not only of political consciousness, as evidenced by his contributions to the Teutsche Liederbuch anthology of German nationalist poem-songs (Lieder), but of religious consciousness as well. As confirmed in the baptismal certificate signed by Schleiermacher -- another proud possession of the grandson [12] -- Karl Gustav Jung renounced the Roman Catholic faith and became an Evangelical Protestant in the Romantic and nationalist mode.

The aftershocks of the grandfather's renunciation of his ancestral faith can still be felt by those touched by the life and work of the grandson. The sudden conversion of the grandfather, his act of apostasy, his angry rejection of Rome, would arguably prove to be one of the most powerful determinants of the destiny of C. G. Jung. The importance of this familial mark of Cain cannot be overstated. [13]"Religion of the heart"Religion mated with German nationalism in the eighteenth century and produced a fever in the people called Pietism. [14] Schleiermacher had been visited by this fever in his youth, and although he forged his own path as a theologian and philosopher, he said his ideas remained closest to this "religion of the heart." To Schleiermacher, the highest form of religion was an "intuition" (Anschauung) of the "Whole," an immediate experience of every particular as part of a whole, of every finite thing as a representation of the infinite. This was the perfect theology for an age of nature-obsessed Romanticism, and at times Schleiermacher's rhetoric, adorned with organic metaphors of the whole derived from nature, shaded into pantheism and mysticism. By 1817, he most certainly infected Karl Jung with it, as he did that entire generation of young patriots through his sermons, his writings, and especially his revisions of the Reformed Protestant liturgy, making it more simple, festive, and Volkish. Additionally, in the decade before he met Jung, he had published translations of Plato and, by his own admission, had become quite influenced by Platonism. This, too, must be remembered when we fantasize about what the older spiritual adviser imparted to the enthusiastic young convert.German Pietism was loosely related to contemporaneous religious movements, such as Quakerism and enthusiastic Methodism in England and America and Quietism and Jansenism in France.

Pietism, however, was to play a key role in developing Volkish self-consciousness and a sense of nation in the politically fragmented German lands. In the spirit of Luther, Pietism was born of disgust with orthodoxies, dogmas, and church hierarchies in the traditional Protestant denominations, making it a form of radical Lutheranism. Pietists dared to question authority and to be suspicious of foreign interpreters of Christianity. They called it a Herzensreligion, a "religion of the heart," a spiritual movement that emphasized feeling, intuition, inwardness, and a personal experience of God. [15] The function of thinking, indeed reason itself, was disparaged and could not be trusted. To experience God, the intellect must be sacrificed. (For example, according to Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, a prominent eighteenth-century Pietist who influenced Schleiermacher and twentieth-century figures Rudolph Otto and Hermann Hesse, only atheists attempted to comprehend God with their mind; the True sought revelation.) [16]

Pietists' mystical enthusiasm is reflected in some of their favorite incendiary metaphors for their ecstatic experiences. It was the fire of the Holy Spirit that must burn within; indeed, it was often said that "the heart must burn." They emphasized the burning experience of "Christ within us" instead of the inanimate, automatic belief in the dogma of a "Christ for us."

Such subtle distinctions had profound implications for German nationalism, for the belief arose in the feeling of group identity bound by common inner experience, a mystical blood-union of necessity, rather than as some thing external existing for an individual. Hence, the Pietist emphasis on service to others as a method of serving God.

Prussia, the most absolutist of the many German political entities, welcomed the Pietists to Berlin. Attracted to Pietism's rejection of the Lutheran clerical hierarchy -- which threatened the overriding legitimacy of the state -- the eighteenth-century rulers of Prussia adopted Pietism's religious philosophy and offered sanctuary to many of its exiled leaders. As populist movements, Pietism and pan-German nationalism were as threatening to the royal rulers of the dozens of German states as to Lutheran clerics, for they challenged the political status quo. Prussia, however, as the strongest of the German states, already presaged its manifest destiny as the unifier of Germany, and so its short-term goals coincided with those of such movements.

Nicholas Boyle, one of Goethe's biographers, described the immense significance of this convergence of affinities for the next two centuries of German religious life and political history:The particular feature of Pietism which makes it of interest to us is its natural affinity for state absolutism. A religion which concentrates to the point of anxiety, not to say hypochondria, on those inner emotions, whether of dryness or abundance, of despair or of confident love of God, from which the individual may deduce the state of his immortal soul; a religion whose members meet for preference not publicly, but privately in conventicles gathered round a charismatic personality who may well not be an ordained minister; a religion who disregards all earthly (and especially all ecclesiastical) differentiation of rank, and sees its proper role in the visible world in charitable activity as nearly as possible harmonious with the prevailing order ... such a religion was tailor-made for a state system in which all, regardless of rank, were to be equally servants of the one purpose; in which antiquated rights and differentiae were to be abolished; and in which ecclesiastical opposition was particularly unwelcome, whether it came from assertive prelates or from vociferous enthusiasts unable to keep their religious lives to themselves. [17]

By the middle of the eighteenth century, German nationalism had become so intertwined with Pietism that the literature of the time blurs distinctions between inner and outer Fatherlands. [18] The "internalized Kingdom of Heaven" became identical with the spiritual soil of the German ancestors, a Teutonic "Land of the Dead." In these patriotic religious tracts the sacrificial deaths of Teutonic heroes such as Arminius (Hermann the German, who defeated the Romans in the Teutoberg forest) and the mythic Siegfried are compared to the crucifixion of Christ, thus equating pagan and Christian saviors. By the early 1800s, this identity became even more explicit. To Ernst Moritz Arndt, the subjective experience of the "Christ within" was reframed in German Volkish metaphors. In his 1816 pamphlet Zur Befreiung Deutschlands ("On the Liberation of Germany"), Arndt urged Germans, "Enshrine in your hearts the German God and German virtue." [19] They did. By the end of the nineteenth century the German God had reawakened and was moving to reclaim his throne after a thousand-year interregnum.The primary literature of Pietism consisted of diaries and autobiographies, most driven by the psychological turn inward so valued as the path to reaching the kingdom of God. These

confessional texts emphasize the spiritual evolution of the diarist. Each account peaks dramatically with the description of what Schleiermacher called the "secret moment," the tremendous subjective experience that completely changed the life course of an individual and became the central, vivid milestone of his or her faith. This experience was known as the Wiedergeburt, the "rebirth" or "regeneration." Sometimes this experience was preceded or accompanied by visions. Several of the more famous texts, such as the autobiography of Heinrich Jung-Stilling, became part of the canon read by educated nineteenth-century Germans.

Several of these spiritual autobiographies were in the library in C. G. Jung's household when he was growing up, and he cites some of them (such as the work of Jung-Stilling) in

MDR and in his seminars. [20]

While MDR is highly unlike usual biographies or autobiographies, its story of Jung's spiritual journey is similar in many ways to the Wiedergeburt testimonies of the Pietists. MDR is indeed the story of Jung's rebirth, but the book diverges from the tradition in one uncanny respect: Rather than recording the renewal of Jung's faith as a "born-again Christian," MDR is

a remarkable confession of Jung's pagan regeneration.Prison and exileTwo years after the Wartburgfest, Karl Jung was arrested by Prussian authorities after a friend of his assassinated a government official. Charged with being a political demagogue, Jung spent the next thirteen months in a Berlin prison.

Sitting in his filthy cell, the stench of human waste ever present, he lamented the sad fact that his medical career in his beloved Fatherland was over before it really began. Losing hope as the months continued to pass, he struggled to resist the temptation to interpret his long prison term as the Creator's revenge for his strident apostasy. His intense desire to participate in the political, cultural, and spiritual union of his Volk, his hatred of the Pope and the Papists, his Pietistic rebirth in the hands of Schleiermacher -- all of these newly flowering branches were suddenly and cruelly chopped from the trunk of his living soul, abandoning him to a lifetime of torturous fantasies that swirled around questions never answered, heroic tasks never completed.

Expelled from Prussia, unable to work in most of the German principalities due to his criminal record, in 1821 Karl Jung fled to Paris, the capital of the recent oppressors of the German peoples. This must have seemed like the ultimate capitulation, but his retreat into the heart of his enemy, this embrace of the negation of all that he thought he was and wanted to be, would bring unintended rewards. Jung tempered his Volkish romanticism and his nationalist activism and redirected his attention and vitality to the practice of medicine. The religious zeal of the new convert that energized him in Berlin was, by necessity, submerged in Roman Catholic France. He married a Frenchwoman and learned to become more cautious politically. Career and home replaced Volkish utopianism as his primary concerns.

In Paris he had the good fortune to meet Alexander von Humboldt, next to Goethe perhaps the most famous German man of science of his age. [21] Humboldt was impressed by the young physician, and upon his recommendation Jung was able to procure work as a surgeon at the famous Hotel Dieu. In 1822, Humboldt wrote a letter recommending Jung to the medical faculty at the University of Basel in Switzerland, where Jung went on to assume the chair in surgery, anatomy, and obstetrics, rising from Dozent (lecturer) to Ordinarius (professor) within the year.

The position Jung assumed was not exactly one of the most coveted in Europe. Between 1806 and 1814, the University of Basel only produced one doctorate in medicine. For many years there was only one instructor in the medical faculty, and often lectures were given to only a single medical student and a few barber-surgeons who only required a little training in bloodletting, nail clipping, and haircutting. To his credit, Jung succeeded in modernizing medical education and research at this institution, and his lasting fame in Basel derives from this pioneering effort. By 1828, Jung was made rector of the university. He became a legendary figure in Basel, and there were many still alive who knew old Professor Doctor Karl Jung when his grandson grew up in Basel and received his own medical training at the university in the late 1890s.

But in 1822 the soul of Karl Jung was still profoundly rooted in his German homeland, and initially he felt alien among the Swiss. He was homesick most of the time, and because the people of Basel spoke their own Swiss-German dialect, he had difficulty understanding and being understood. He came to Switzerland as an exile, knowing in all likelihood he could never go home again. Although geographically close to Germany, Basel was psychologically remote, almost otherworldly, "in a comer of the world, across from the Fatherland." Perhaps most painful was his loss of national identity: "I am no longer a German," he lamented. [22]

As he threw himself into the building of new hospitals and clinics (including one for the mentally alienated), Karl Jung forged new relationships and became a prominent citizen and a relatively wealthy man. To rekindle the spirit of belonging to a brotherhood of idealists, which he missed dearly, Jung joined a powerful secret society. In time, he became its supreme leader in Switzerland.

Reconstructing the Temple of Solomon with Philosopher's StonesKarl Jung first became acquainted with Freemasonry during his student days. There were many thriving lodges in Paris, but as a German he had little chance of joining. Opportunities were plentiful in Switzerland, however. As a stranger in a strange land, Jung gravitated naturally toward the local Masonic community as a way of assimilating into Swiss society. Then, as now, Freemasonry provided unique opportunities for making friends and advancing one's career through a network of individuals from a variety of occupations and social, political, and religious backgrounds. In Switzerland, as elsewhere, Masonic lodges were places where men could gather outside their family, their church, and bodies of government. Often driven by the ethical idealism of the Enlightenment, Masonic lodges were places where nationalists could congregate and conspire, where anti-papists could vent their spleens, and where philanthropic projects could be planned and carried out. Jung's own hospital and clinic projects in Basel were no doubt expedited by his relationships with the secret Masonic brotherhood. [23]

There was another side to Freemasonry, however: its esoteric approach to religion. Behind the not-so-secret rites and rituals, grades and degrees, breathed a very different order. Spiritual growth, Freemasons believed, was best nurtured in a secret society of those farther along the illuminated path who initiated those less enlightened.

When Karl Jung first encountered Freemasonry in Germany, it was a movement still recovering from its 1784 banning by the Bavarian government, which claimed to have discovered a radical republican conspiracy within the Illuminati, the exalted inner circle of the Masons. Bavaria made it a capital crime to recruit others to this secret society, and most of the other German governments followed suit. In Germany and in Switzerland, Freemasons continued to assemble and enact rituals under the ruse of being patriotic clubs or philanthropic societies. Not surprisingly, during the Napoleonic wars they became efficient vehicles for organizing resistance to the French.

Traditionally, the German Freemasons were split into two sometimes contentious camps. One advocated the organizational goal of fostering Enlightenment virtues of liberty, equality, and ethical universalism in the German peoples. Its ideological rival, a faction that generally referred to itself as Rosicrucian, saw itself as the bearer of the torch for the ancient theology handed down to the first Freemasons from the prisci theologi, the "pristine theologians," from whom all wisdom is derived. [24] Although Freemasonry did not emerge with any force in Germany until the 1740s, the Masonic Rosicrucians claimed that they were the keepers of occult knowledge passed to them by the ancient Rosicrucians, whose symbol was the Christian cross wrapped in roses. The wisdom of the ancients was passed from man to man in secret through a series of initiatory steps or grades or degrees. The Grand Masters were the true adepts, experts in the arcane, even allegedly gifted with healing powers and second sight.

From its inception in the mid-1600s, Freemasonry has been related to the mythology of the Rosicrucians, although there is no evidence that such a secret society ever existed. [25] The fascination with Rosicrucianism can be traced to the appearance of two anonymous pamphlets published in Cassel, the German Fama (1614) and the Latin Confessio (1615); and to a German book by Johann Valentin Andreae called the Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosencreutz (The chemical wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz), which appeared in 1616. The two manifestos tell the story of "Father C.R.C.," also known as "Christian Rosenkreutz," the founder of an ancient order or brotherhood -- symbolized by a red cross and a red rose -- that had been secret but now wanted new members. The appearance of these mysterious invitations ignited considerable speculation, and soon copycat secret societies were formed, many claiming to be the true keepers of the Rosicrucian flame. It was out of this Rosicrucian mania that Freemasonry was born.

The legend that Karl Jung learned in the early nineteenth century is still very much the basis of arcane Masonic lore today: the first Freemasons were the stonemasons who built the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. During the construction, some of the masons were initiated into cosmic mysteries related to geometry and mathematics and, it was later said, alchemy. Each stone they used to build the Temple was not an ordinary stone, but an alchemical Philosopher's Stone. This knowledge was passed secretly from mason to mason through the ages to the men in the medieval guilds who built the magnificent cathedrals. Together, the esoteric goal of each of the Masonic brethren was to metaphysically rebuild the sacred Temple of Solomon within each Masonic lodge. In Masonic lore, the Philosopher's Stone has many names. Sometimes it is called the Word of God, and the path of illumination is described as the search for the lost Ark of the Covenant. Throughout, we find the collective fantasy of a mutual journey, a quest, a search for the Holy Grail in its myriad manifestations. Above all, the ability to keep a secret was the key to the spiritual advancement of each individual.

In truth, Freemasonry probably did arise out of guilds of masons, and master masons did have secret handshakes and coded knowledge that apprentices would not know. Out of these guilds of skilled craftsmen emerged secret societies that transmitted philosophies about the moral and mystical interpretation of building. Eventually, these "speculative masons" ritualized the passage of knowledge within the masonic-guild structure and the practice of keeping secrets that allowed masters to recognize their members.

Unlike their brethren to the north, the Swiss lodges did not close down in the purges of the late 1780s and so were a haven for German Freemasons, both Illuminatist and Rosicrucian. When Karl Jung knew them, each, to a greater or lesser degree, continued the traditions of Freemasonry: as vanguard proponents of Enlightenment civic virtues and as an occult brotherhood united by the symbols of the rose and the cross. The secret rituals of initiation demanded the wearing of special caps and aprons, the recitation of special arcane incantations, and the mastery of the esoteric interpretations of symbols of transformation that were hewn from Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, and especially alchemy -- occult philosophies thus quite familiar to Grand Master Jung. Even his personal image of God as the "eternal Space" conjures up Masonic images of the interior of the Temple of Solomon. In fact, his identity as a Freemason was so important to him that he added such traditional Masonic symbols as an alchemical gold star to the Jung family coat of arms. In the twentieth century, his grandson would paint these Masonic emblems from the family crest on the ceiling of his Tower in Bollingen. Other arcane symbols familiar to his grandfather would be carved into walls and special monuments, each stone worked by his own hands in the old way.

The rose, the cross, and the mysteriesGoethe enters our story at this point, less as an apparition than as a visitation from a god.

There were many affinities between these two contemporaries, Karl Gustav Jung and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Goethe was also a Freemason, but unlike Jung, he did not remain ardent about the veiled brotherhood for very long.

While in Weimar, Goethe applied for membership to the Amalia lodge, as it was called, in 1780. By 1782, he had risen rapidly to become a Master Mason, and in February 1783 he rose to the exalted inner circle of Illuminists. Having mastered all the secret handshakes, the Masonic myths of origin, the alchemical metaphors for personal transformation and growth, the progression of occult symbols associated with each grade -- such as a casket with the Seal of Solomon on it and an image of the Ark of the Covenant-he expressed dissatisfaction, indeed annoyance, that he had been so naive to believe that some great secret would be revealed to him if he could only reach the lofty inner circle. A few weeks after finally reaching this circle, Goethe said to a friend, "They say you can best get to know a man when he is at play and now I have reached the ark of the covenant I have nothing to add. To the wise all things are wise, to the fool foolish." [26]

Goethe later blended portions of the arcane knowledge and symbolism introduced to him through Freemasonry in Faust, but two pieces of literature in particular were more directly influenced by his gaming with the "brethren." One was a Masonic comedy, Der Gross-Cophta (The grand kophta), which he wrote in 1790. The protagonist of this play, a young knight, joins a special brotherhood that claims to be dedicated to only the most spiritual and noblest of aims. Indeed, this altruistic brotherhood believes its work is the salvation of a misguided humanity. However, the young knight soon realizes that he has been deceived and that the brotherhood has much more base and pecuniary motives. With his missionary zeal to save the souls of his fellow humans destroyed, he wonders what to do with his misspent idealism. Wisely, the young knight realizes, "Fortunate he, if it is still possible for him to find a wife or a friend, on whom he can bestow individually what was intended for the whole human race." [27]

Goethe's disillusionment with his Masonic involvement is nakedly revealed in the hard-earned wisdom of the young knight. However, his humanistic idealism and his earlier hopes for a true Holy Order of the Rose and the Cross that would unite humankind in spiritual brotherhood appear in a second work, never completed, that he called Die Geheimnisse (The mysteries). [28] Both Jungs, grandfather and grandson, committed it to their hearts.

The work begins, as all initiations do, with a quest. A certain Brother Markus is traveling through the mountains during Holy Week and seeks a place to sleep in an unfamiliar monastery. As the sun sinks behind the mountain peaks, the bells of the monastery suddenly start to ring, filling him with hope and consolation. As he nears the gates he sees a Christian cross. Suddenly, he realizes it is not the usual crucifix, but a remarkable sight that he has never seen before: a cross tightly wound with roses. "Who delivered these roses to the cross?" he wonders. The tower gate opens and Brother Markus is greeted and invited inside by a wise old man whose openness, innocence, and gestures make him seem like a man from another world. Soon Brother Markus is welcomed by a community of gray-haired knights who are too old for adventure but are proud men who have all lived life to the fullest. They have chosen to spend their remaining years in peaceful contemplation, and they accept no new brother if he is still "young and his heart has led him to renounce the world too soon."

Yet all is not in harmony at the monastery. Their founder and master, Brother Humanus, has informed his brethren that he will be leaving them soon. Brother Markus hears wondrous tales about the childhood of Humanus, which is filled with such miracles as making a spring flow out of dry stone with the touch of a sword. He is entranced by the wisdom of Humanus ("the Holy One, the Wise One, the best man I've ever laid eyes on"), but hears him relate something incomprehensible:

Von der Gewalt, die all Wesen bindet,

Befreit der Mensch sich, der sich ueberwindet

From the force that binds all beings,

The man frees himself who overcomes himself.

Brother Markus is led to a great hall and is shown something rarely seen: a ritual room -- resembling a chapel -- in which thirteen seats line the walls, one for the master of the order and twelve for the knights. Behind the seat of each knight hangs a unique coat of arms with unfamiliar symbols of faraway lands. Brother Markus sees that the seats· are arranged around a cross with rose branches wound around it. Swords and lances and other weapons are also scattered about the chamber. It is a holy place, but unlike any chapel he's ever seen. [29]

That night, Brother Markus gazes out of his window and sees "a strange light wandering through the garden." He then is astounded by the sight of three young men with torches, clad in white garments, off in the distance. Who are they? We'll never know, for here Goethe's fragment comes to its premature end.

Goethe decided to publish it as is, but in response to queries on April 9, 1816, in the prominent newspaper Morganblatt, he published a description of how Die Geheimnisse would end. The twelve knights were to each represent a different religion and nationality, and each would have then had his turn to narrate a tale about the remarkable life of Humanus. Together these stories would comprise the entire range of human religious experience, the unity of which is symbolized by this Order of the Rosy Cross. Goethe revealed that the poem would climax with the Easter death of Humanus, who then would be replaced by Brother Markus, of course, as grand master of the order.

***

Exactly one hundred years after Die Geheimnisse appeared in print, Carl Gustav Jung stood before a historic gathering of his disciples in Zurich and delivered an inspirational address that spoke almost exclusively of spiritual matters: of self-deification, of overcomings, of disturbing the Dead, and of this poem. [30] The occasion of his talk was the founding of the Psychological Club, based on the new psychological theories he derived from the insights he received from his own visions and encounters with Philemon, his spiritual master.

To describe the essence of their collective purpose, as he saw it, he invoked the Grail-knights imagery of Wagner's Parsifal and the Rosicrucian brotherhood in Goethe's fragmentary fantasy. Jung framed the Psychological Club within these ancient German motifs of holy orders of knights in search of occult knowledge, healing powers, and especially spiritual redemption. By mentioning this poem, and by invoking the spirit of Goethe, Jung was also paying homage to his ancestors, to his ancestral soul. I mean this in several senses: as homage to the Dead, to his own fathers, and to the ancestors of the Fatherland as spirits who have traveled the same paths on the same Grail quest. Further, there is good reason to believe that as he delivered this inaugural address, Carl Jung believed that his grandfather, Karl Gustav Jung, was the bastard son of the great Goethe. In an age and culture obsessed with the commanding influence of heredity and race on an individual, the possibility that Goethe was his great-grandfather was a very powerful fantasy.

Near the end of his life, however, Jung changed the story. No longer was he merely the blood-kin of the greatest genius the German Volk had produced. He believed instead that he was an eternal recurrence, an avatar, a revenant. Carl Jung believed himself to be, literally, the reincarnation of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Atavisms and IlluminatiThe family fable -- discounted by everyone with an amused smile, including by Carl Jung himself sometimes -- lives in the tradition of all myths of erotic union between mortal women and the gods. Many within the Jung family and without would occasionally tell the story furtively, relishing the role of an insider privy to celebrity gossip, that the mother of Professor Doctor Karl Jung had a "spring to the side" as they say in German, an extramarital tryst with Goethe that resulted in Karl, so the story goes. True or not, Carl Jung enjoyed telling this anecdote throughout his life. Its origins are not known, but there is good reason to suspect it was alive even during Karl Jung's lifetime. Jung said he first heard this story from strangers when he was a schoolboy, which must have only reinforced the possibility that it might be more than a frivolous family story.

Carl Jung marveled at the similarities between his grandfather and Goethe. Both were vital, energetic, productive men who dominated, intellectually and temperamentally, most people. Both were scientists as well as poets, influenced by Pietism in their youth and disaffected from it in their maturity. Both were Germans and Freemasons -- Illuminati, in fact -- and above all, true Romantics until the end. They both seemed larger than life, daemonic, godlike, more like forces of nature than men.

Carl Jung knew that he shared many of the temperamental qualities of his grandfather (and therefore, by extension, of Goethe). By his own admission, it was the legend of his grandfather, not the living example of his father, against which Jung constantly measured himself as a young man.

In a seminar he gave in Zurich in 1925, Carl Jung expressed his belief in the idea of "ancestor possession" -- that is, that certain hereditary units would become activated under certain circumstances in one's life, allowing the spirit of one's ancestor to then "take over" one's actions. Jung gave the example of an "imaginary normal man" who, on the surface, never indicated a capacity for leadership but in whom, when put in a position of power, the "ancestral unit" of a leader somewhere in the family past was awakened. [31] These ancestral units were a far cry from anything resembling genetics but were in sympathy with nineteenth-century biological theories that were on the verge of dying out. Jung also used this concept in a spiritualist sense. It is hard not to imagine him fantasizing about his own grandfather, and perhaps Goethe, in these terms. During the first sixty years of Jung's life, biology and spirituality were fused in ways difficult -- indeed, distasteful -- for us to imagine. And so, the scientist in Jung no doubt found support in the surviving Lamarckian currents in German biology to keep the possibility open that the inherited personality characteristics of his great-grandfather, those blinding rays of Goethe's genius, were radiating from his own personality.

But the scientist in Jung would always remain just his "number one personality," his day side, his compromise to a skeptical world that insisted on erasing magic from life, a feat as impossible to the night side of Jung' s personality as removing the stars from the evening sky. His belief in reincarnation is one of many renditions of a melody of eternal recurrence that plays throughout Jung's inner and outer lives.

Jung felt a special kinship with Goethe by age fifteen, after his first of many readings of Faust. "It poured into my soul like a miraculous balm," he recalled. [32] Faust, the learned scholar who has many doctorates but is "no wiser than before," is the seeker of truth who sacrifices the realm of the intellect to turn to the magical invocation of spirits for occult wisdom. Jung regarded Goethe's Faust as a new dispensation, a product of revelation, a contribution to the world of religious experience as a new sacred text. In 1932 he wrote in a letter, "Faust is the most recent pillar in that bridge of the spirit which spans the morass of world history, beginning with the Gilgamesh epic, the I Ching, the Upanishads, the Tao-te-Ching, the fragments of Heraclitus, and continuing in the Gospel of St. John, the letters of St. Paul, in Meister Eckhardt and in Dante." [33] In his eyes, Goethe became "a prophet," especially for confirming the autonomous reality of "evil" and "the mysterious role it played in delivering man from darkness and suffering." [34]

The public expression of Jung's position on reincarnation, to be found in the chapter "On Life After Death" in MDR, is that he keeps "a free and open mind" and is not "in a position to assert a definite opinion," while at the same time several cryptic pages are devoted to "hints" of his past lives. In fact, Jung says at one point, "Recently, however, I observed in myself a series of dreams which would seem to describe the process of reincarnation in a deceased person of my acquaintance." After remarking that he has "never come across any such dreams in other persons," he has no basis for comparison and therefore chooses "not to go into it any further." He does admit, however, that "after this experience I view the problem of reincarnation with somewhat different eyes." [35] But we know from archival sources that his private opinion was that these dreams confirmed to him that he had been Goethe in a previous incarnation. [36]

"I know no answer to the question of whether the karma which I live is the outcome of my past lives, or whether it is not rather the achievement of my ancestors, whose heritage comes together in me," Jung confessed in MDR. "Am I a combination of the lives of these ancestors and do I embody these lives again? Have I lived before in the past as a specific personality, and did I progress so far in that life that I am now able to seek a solution? I do not know." [37]

Yet reincarnation implies many existences, and Jung did not end his metaphysical antecedents with Goethe. In replies to questions about his possible past lives, Jung sometimes claimed he was Meister Eckhardt. [38] Eckhardt, born in Erfurt in 1260, was considered one of the most profoundly philosophical and original of all the Christian mystics. Eckhardt (like Jung) used poetical expression and paradox to convey the meaning of his beliefs about God, which can be easily interpreted as pantheism. In 1329, Pope John XXII condemned portions of his writings as heretical.

The addition of Eckhardt to Goethe brings Jung's inner fatherland into focus. The fact that he believed in an immortal soul or life after death or even reincarnation is no revelation to those who read him, or who read between the lines of MDR. As Jung himself maintained, beliefs about such matters are always deeply subjective and inordinately personal, which is precisely why Jung's speculations about his own past lives are so revealing -- and so difficult to accept unless we first understand the worlds in which he lived, both inner and outer fatherlands.

The ethnic pattern of his incarnations is what is so important. His own logic mirrors that of his culture, and is consistent, indisputable, and racial: Jung is the perfected result of the evolution of his ancestors, whose heritage converges in him. And it is always German genius, the genius of his Volk.