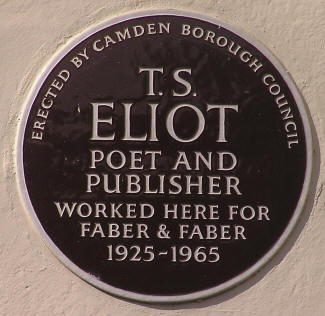

by T.S. Eliot

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Table of Contents:

• Preface

• Chapter 1

• Chapter 2

• Chapter 3

• Chapter 4

• Notes

• Postscript

• Appendix

Liberalism still permeates our minds and affects our attitude towards much of life....For it is something which tends to release energy rather than accumulate it, to relax, rather than to fortify. It is a movement not so much defined by its end, as by its starting point; away from, rather than towards, something definite....By destroying traditional social habits of the people, by dissolving their natural collective consciousness into individual constituents, by licensing the opinions of the most foolish, by substituting instruction for education, by encouraging cleverness rather than wisdom, the upstart rather than the qualified, by fostering a notion of getting on to which the alternative is a hopeless apathy, Liberalism can prepare the way for that which is its own negation: the artificial, mechanised or brutalised control which is a desperate remedy for its chaos....In religion, Liberalism may be characterised as a progressive discarding of elements in historical Christianity which appear superfluous or obsolete, confounded with practices and abuses which are legitimate objects of attack. But as its movement is controlled rather by its origin than by any goal, it loses force after a series of rejections, and with nothing to destroy is left with nothing to uphold and with nowhere to go....

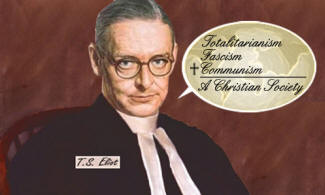

[W]hat I mean by a political philosophy is not merely even the conscious formulation of the ideal aims of a people, but the substratum of collective temperament, ways of behaviour and unconscious values which provides the material for the formulation. What we are seeking is not a programme for a party, but a way of life for a people: it is this which totalitarianism has sought partly to revive, and partly to impose by force upon its peoples. Our choice now is not between one abstract form and another, but between a pagan, and necessarily stunted culture, and a religious, and necessarily imperfect culture....

The fundamental objection to fascist doctrine, the one which we conceal from ourselves because it might condemn ourselves as well, is that it is pagan....

[T]he only alternative to a progressive and insidious adaptation to totalitarian worldliness for which the pace is already set, is to aim at a Christian society....To those who realise what a well organised pagan society would mean for us, there is nothing to say. But it is as well to remember that the imposition of a pagan theory of the State does not necessarily mean a wholly pagan society. A compromise between the theory of the State and the tradition of society exists in Italy, a country which is still mainly agricultural and Catholic. The more highly industrialised the country, the more easily a materialistic philosophy will flourish in it, and the more deadly that philosophy will be. Britain has been highly industrialised longer than any other country. And the tendency of unlimited industrialism is to create bodies of men and women -- of all classes -- detached from tradition, alienated from religion, and susceptible to mass suggestion: in other words, a mob. And a mob will be no less a mob if it is well fed, well clothed, well housed, and well disciplined.

The Liberal notion that religion was a matter of private belief and of conduct in private life, and that there is no reason why Christians should not be able to accommodate themselves to any world which treats them good-naturedly, is becoming less and less tenable....When the Christian is treated as an enemy of the State, his course is very much harder, but it is simpler. I am concerned with the dangers to the tolerated minority; and in the modern world, it may turn out that the most intolerable thing for Christians is to be tolerated....

[T]he only possibility of control and balance is a religious control and balance ... the only hopeful course for a society which would thrive and continue its creative activity in the arts of civilisation, is to become Christian. That prospect involves, at least, discipline, inconvenience and discomfort: but here as hereafter the alternative to hell is purgatory....

I conceive then of the Christian State as of the Christian Society under the aspect of legislation, public administration, legal tradition, and form....with what kind of State can the Church have a relation? By this I mean a relation of the kind which has hitherto obtained in England...It must be clear that I do not mean by a Christian State one in which the rulers are chosen because of their qualifications, still less their eminence, as Christians. A regiment of Saints is apt to be too uncomfortable to last....The Christian and the unbeliever do not, and cannot, behave very differently in the exercise of office; for it is the general ethos of the people they have to govern, not their own piety, that determines the behaviour of politicians. One may even accept F. S. Oliver's affirmation -- following Buelow, following Disraeli -- that real statesmen are inspired by nothing else than their instinct for power and their love of country. It is not primarily the Christianity of the statesmen that matters, but their being confined, by the temper and traditions of the people which they rule, to a Christian framework within which to realise their ambitions and advance the prosperity and prestige of their country. They may frequently perform un-Christian acts; they must never attempt to defend their actions on un-Christian principles....

I should not expect the rulers of a Christian State to be philosophers, or to be able to keep before their minds at every moment of decision the maxim that the life of virtue is the purpose of human society -- virtuosa ... vita est congregationis humanae finis; but they would neither be self-educated, nor have been submitted in their youth merely to that system of miscellaneous or specialised instruction which passes for education: they would have received a Christian education. The purpose of a Christian education would not be merely to make men and women pious Christians.... A Christian education would primarily train people to be able to think in Christian categories, though it could not compel belief and would not impose the necessity for insincere profession of belief. What the rulers believed, would be less important than the beliefs to which they would be obliged to conform. And a skeptical or indifferent statesman, working within a Christian frame, might be more effective than a devout Christian statesman obliged to conform to a secular frame. For he would be required to design his policy for the government of a Christian Society....

Among the men of state, you would have as a minimum, conscious conformity of behaviour. In the Christian Community that they ruled, the Christian faith would be ingrained, but it requires, as a minimum, only a largely unconscious behaviour; and it is only from the much smaller number of conscious human beings, the Community of Christians, that one would expect a conscious Christian life on its highest social level....

We must abandon the notion that the Christian should be content with freedom of cultus, and with suffering no worldly disabilities on account of his faith. However bigoted the announcement may sound, the Christian can be satisfied with nothing less than a Christian organisation of society -- which is not the same thing as a society consisting exclusively of devout Christians. It would be a society in which the natural end of man -- virtue and well-being in community -- is acknowledged for all, and the supernatural end -- beatitude -- for those who have the eyes to see it....

It should not be necessary for the ordinary individual to be wholly conscious of what elements are distinctly religious and Christian, and what are merely social and identified with his religion by no logical implication. I am not requiring that the community should contain more 'good Christians' than one would expect to find under favourable conditions. The religious life of the people would be largely a matter of behaviour and conformity; social customs would take on religious sanctions; there would no doubt be many irrelevant accretions and local emphases and observances -- which, if they went too far in eccentricity or superstition, it would be the business of the Church to correct, but which otherwise could make for social tenacity and coherence....

'[T]he Church within the Church'. These will be the consciously and thoughtfully practising Christians, especially those of intellectual and spiritual superiority....

In a Christian Society education must be religious, not in the sense that it will be administered by ecclesiastics, still less in the sense that it will exercise pressure, or attempt to instruct everyone in theology, but in the sense that its aims will be directed by a Christian philosophy of life. It will no longer be merely a term comprehending a variety of unrelated subjects undertaken for special purposes or for none at all....

You cannot expect continuity and coherence in politics, you cannot expect reliable behaviour on fixed principles persisting through changed situations, unless there is an underlying political philosophy: not of a party, but of the nation. You cannot expect continuity and coherence in literature and the arts, unless you have a certain uniformity of culture, expressed in education by a settled, though not rigid agreement as to what everyone should know to some degree, and a positive distinction -- however undemocratic it may sound -- between the educated and the uneducated. I observed in America, that with a very high level of intelligence among undergraduates, progress was impeded by the fact that one could never assume that any two, unless they had been at the same school under the influence of the same masters at the same moment, had studied the same subjects or read the same books, though the number of subjects in which they had been instructed was surprising. Even with a smaller amount of total information, it might have been better if they had read fewer, but the same books. In a negative liberal society you have no agreement as to there being any body of knowledge which any educated person should have acquired at any particular stage: the idea of wisdom disappears, and you get sporadic and unrelated experimentation. A nation's system of education is much more important than its system of government; only a proper system of education can unify the active and the contemplative life, action and speculation, politics and the arts....

The obvious secularist solution for muddle is to subordinate everything to political power: and in so far as this involves the subordination of the money-making interests to those of the nation as a whole, it offers some immediate, though perhaps illusory relief: a people feels at least more dignified if its hero is the statesman however unscrupulous, or the warrior however brutal, rather than the financier. But it also means the confinement of the clergy to a more and more restricted field of activity, the subduing of free intellectual speculation, and the debauching of the arts by political criteria. It is only in a society with a religious basis -- which is not the same thing as an ecclesiastical despotism -- that you can get the proper harmony and tension, for the individual or for the community....

The Community of Christians is not an organisation, but a body of indefinite outline; composed of both clergy and laity, of the more conscious, more spiritually and intellectually developed of both. It will be their identity of belief and aspiration, their background of a common system of education and a common culture, which will enable them to influence and be influenced by each other, and collectively to form the conscious mind and the conscience of the nation....

The problem [of Church and State] is one of concern to every Christian country -- that is, to every possible form of Christian society. It will take a different form according to the traditions of that society -- Roman, Orthodox, or Lutheran. It will take still another form in those countries, obviously the United States of America and the Dominions, where the variety of races and religious communions represented appears to render the problem insoluble....I believe that if these countries are to develop a positive culture of their own, and not remain merely derivatives of Europe, they can only proceed either in the direction of a pagan or of a Christian society. I am not suggesting that the latter alternative must lead to the forcible suppression, or to the complete disappearance of dissident sects; still less, I hope, to a superficial union of Churches under an official exterior, a union in which theological differences would be so belittled that its Christianity might become wholly bogus. But a positive culture must have a positive set of values, and the dissentients must remain marginal, tending to make only marginal contributions....

If my outline of a Christian society has commanded the assent of the reader, he will agree that such a society can only be realised when the great majority of the sheep belong to one fold. To those who maintain that unity is a matter of indifference, to those who maintain even that a diversity of theological views is a good thing to an indefinite degree I can make no appeal. But if the desirability of unity be admitted, if the idea of a Christian society be grasped and accepted, then it can only be realised, in England, through the Church of England....

In matters of dogma, matters of faith and morals, [the Church of a Christian Society] will speak as the final authority within the nation; in more mixed questions it will speak through individuals. At times, it can and should be in conflict with the State, in rebuking derelictions in policy, or in defending itself against encroachments of the temporal power, or in shielding the community against tyranny and asserting its neglected rights, or in contesting heretical opinion or immoral legislation and administration. At times, the hierarchy of the Church may be under attack from the Community of Christians, or from groups within it: for any organisation is always in danger of corruption and in need of reform from within....

The effect on the mind of the people of the visible and dramatic withdrawal of the Church from the affairs of the nation, of the deliberate recognition of two standards and ways of life, of the Church's abandonment of all those who are not by their wholehearted profession within the fold -- this is incalculable; the risks are so great that such an act can be nothing but a desperate measure....But if one believes, as I do, that the great majority of people are neither one thing nor the other, but are living in a no man's land, then the situation looks very different....

I think that the tendency of the time is opposed to the view that the religious and the secular life of the individual and the community can form two separate and autonomous domains....[T]he totalitarian tendency is against it, for the tendency of totalitarianism is to re-affirm, on a lower level, the religious-social nature of society. And I am convinced that you cannot have a national Christian society, a religious-social community, a society with a political philosophy founded upon the Christian faith, if it is constituted as a mere congeries of private and independent sects. The national faith must have an official recognition by the State, as well as an accepted status in the community and a basis of conviction in the heart of the individual....

[N]o one to-day can defend the idea of a National Church, without balancing it with the idea of the Universal Church, and without keeping in mind that truth is one and that theology has no frontiers....I have maintained that the idea of a Christian society implies, for me, the existence of one Church which shall aim at comprehending the whole nation. Unless it has this aim, we relapse into that conflict between citizenship and church membership, between public and private morality, which to-day makes moral life so difficult for everyone, and which in turn provokes that craving for a simplified, monistic solution of statism or racism which the National Church can only combat if it recognises its position as a part of the Universal Church....the allegiance of the individual to his own Church is secondary to his allegiance to the Universal Church. Unless the National Church is a part of the whole, it has no claim upon me....even in a Christian society as well organised as we can conceive possible in this world, the limit would be that our temporal and spiritual life should be harmonised: the temporal and spiritual would never be identified. There would always remain a dual allegiance, to the State and to the Church, to one's countrymen and to one's fellow-Christians everywhere, and the latter would always have the primacy. There would always be a tension; and this tension is essential to the idea of a Christian society, and is a distinguishing mark between a Christian and a pagan society....

To identify any particular form of government with Christianity is a dangerous error: for it confounds the permanent with the transitory, the absolute with the contingent. Forms of government, and of social organisation, are in constant process of change, and their operation may be very different from the theory which they are supposed to exemplify.... Those who consider that a discussion of the nature of a Christian society should conclude by supporting a particular form of political organisation, should ask themselves whether they really believe our form of government to be more important than our Christianity...

This essay is not intended to be either an anti-communist or an anti-fascist manifesto....

I have tried to restrict my ambition of a Christian society to ... men whose Christianity is communal before being individual....

[W]e have to remember that the Kingdom of Christ on earth will never be realised, and also that it is always being realised....the overwhelming pressure of mediocrity, sluggish and indomitable as a glacier, will mitigate the most violent, and depress the most exalted revolution....A wholly Christian society might be a society for the most part on a low level; it would engage the cooperation of many whose Christianity was spectral or superstitious or feigned, and of many whose motives were primarily worldly and selfish....

I have, it is true, insisted upon the communal, rather than the individual aspect: a community of men and women, not individually better than they are now, except for the capital difference of holding the Christian faith. But their holding the Christian faith would give them something else which they lack: a respect for the religious life, for the life of prayer and contemplation, and for those who attempt to practise it....I cannot conceive a Christian society without religious orders, even purely contemplative orders, even enclosed orders....

We may say that religion, as distinguished from modern paganism, implies a life in conformity with nature. It may be observed that the natural life and the supernatural life have a conformity to each other... It would perhaps be more natural, as well as in better conformity with the Will of God, if there were more celibates and if those who were married had larger families.... I would not have it thought that I condemn a society because of its material ruin, for that would be to make its material success a sufficient test of its excellence....We need to know how to see the world as the Christian Fathers saw it....We need to recover the sense of religious fear, so that it may be overcome by religious hope....

As political philosophy derives its sanction from ethics, and ethics from the truth of religion, it is only by returning to the eternal source of truth that we can hope for any social organisation which will not, to its ultimate destruction, ignore some essential aspect of reality....If you will not have God (and He is a jealous God) you should pay your respects to Hitler or Stalin....

Might one suggest that the kitchen, the children and the church could be considered to have a claim upon the attention of married women? or that no normal married woman would prefer to be a wage-earner if she could help it?....

Fascist doctrine. I mean only such doctrine as asserts the absolute authority of the state, or the infallibility of a ruler. 'The corporative state', recommended by Quadragesimo Anno, is not in question. The economic organisation of totalitarian states is not in question. The ordinary person does not object to fascism because it is pagan, but because he is fearful of authority, even when it is pagan....

The red herring of the German national religion. I cannot hold such a low opinion of German intelligence as to accept any stories of the revival of pre-Christian cults....

It may be opportune at this point to say a word about the attitude of a Christian Society towards Pacifism....I cannot but believe that the man who maintains that war is in all circumstances wrong, is in some way repudiating an obligation towards society; and in so far as the society is a Christian society the obligation is so much the more serious. Even if each particular war proves in turn to have been unjustified, yet the idea of a Christian society seems incompatible with the idea of absolute pacifism; for pacifism can only continue to flourish so long as the majority of persons forming a society are not pacifists....The notion of communal responsibility, of the responsibility of every individual for the sins of the society to which he belongs, is one that needs to be more firmly apprehended; and if I share the guilt of my society in time of 'peace', I do not see how I can absolve myself from it in time of war, by abstaining from the common action....

[T]he society which is coming into existence, and which is advancing in every country whether 'democratic' or 'totalitarian', is a lower middle class society: I should expect the culture of the twentieth century to belong to the lower middle class as that of the Victorian age belonged to the upper middle class or commercial aristocracy....is it likely to provide anything more important than, for example, a lower middle class Royal Academy instead of one supplying portrait painters for aldermen?...I mean by a 'lower middle class society' one in which the standard man legislated for and catered for, the man whose passions must be manipulated, whose prejudices must be humoured, whose tastes must be gratified, will be the lower middle class man. He is the most numerous, the one most necessary to flatter....

A main part of the problem, as regards the actual Church and its existing members, is the defective realisation among us of the fundamental fact that Christianity is primarily a Gospel-message, a dogma, a belief about God and the world and man, which demands of man a response of faith and repentance. The common failure lies in putting the human response first, and so thinking of Christianity as primarily a religion. Consequently there is among us a tendency to view the problems of the day in the light of what is practically possible, rather than in the light of what is imposed by the principles of that truth to which the Church is set to bear witness....

The Church is not merely for the elect -- in other words, those whose temperament brings them to that belief and that behaviour. Nor does it allow us to be Christian in some social relations and non-Christian in others. It wants everybody, and it wants each individual as a whole. It therefore must struggle for a condition of society which will give the maximum of opportunity for us to lead wholly Christian lives, and the maximum of opportunity for others to become Christians. It maintains the paradox that while we are each responsible for our own souls, we are all responsible for all other souls, who are, like us, on their way to a future state of heaven or hell....

To those who deny, or do not fully accept, Christian doctrine, or who wish to interpret it according to their private lights such resistance often appears oppressive. To the unreasoning mind the Church can often be made to appear to be the enemy of progress and enlightenment.

-- The Idea of a Christian Society, by T.S. Eliot