Eugenics in Evolutionary Perspective

by Sir Julian Huxley, M.A., D.Sc., F.R.S.

October, 1962

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

I AM HONOURED AT having been twice asked to give the Eugenics Society's Galton Lecture. The first occasion was a quarter of a century ago, when Lord Horder was our President, and I am proud of the remarks which he and my brother Aldous made about these.

Let me begin by broadly outlining how eugenics looks in our new evolutionary perspective. Man, like all other existing organisms, is as old as life. His evolution has taken close on three billion years. During that immense period he -- the line of living substance leading to Homo sapiens -- has passed through a series of increasingly high levels of organization. His organization has been progressively improved, to use Darwin's phrase, from some submicroscopic gene-like state, through a unicellular to a two-layered and a metazoan stage, to a three-layered type with many organ-systems, including a central nervous system and simple brain, on to a chordate with notochord and gill-slits, to a jawless and limbless vertebrate, to a fish, then to an amphibian, a reptile, an unspecialized insectivorous mammal, a lemuroid, a monkey with much improved vision, heightened exploratory urge and manipulative ability, an ape-like creature, and finally through a protohominid australopith to a fully human creature, big-brained and capable of true speech.

This astonishing process of continuous advance and biological improvement has been brought about through the operation of natural selection -- the differential reproduction of biologically beneficial combinations of mutant genes, leading to the persistence, improvement and multiplication of some strains, species and patterns of organization and the reduction and extinction of others, notably to a succession of so-called dominant types, each achieving a highly successful new level of organization and causing the reduction of previous dominant types inhabiting the same environment. During its period of dominance, which may last up to a hundred million years or so, the new type itself becomes markedly improved, whether by specialization of single subtypes like the horses or elephants, or by an improvement in general organization, as happened with the mammalian type in general at the end of the Oligocene. Eventually no further improvement is possible, and further advance can only occur through the breakthrough of one line to a radically new type of organization, as from reptile to mammal.

In biologically recent times, one primate line broke through from the mammalian to the human type of organization. With this, the evolutionary process passed a critical point, and entered on a new state or phase, the psychosocial phase, differing radically from the biological in its mechanism, its tempo, and its results. As a result, man has become the latest dominant type in the evolutionary process, has multiplied enormously, has achieved miracles of cultural evolution, has reduced or extinguished many other species, and has radically affected the ecology and indeed the whole evolutionary process of our planet. Yet he is a highly imperfect creature. He carries a heavy burden of genetic defects and imperfections. As a psychosocial organism, he has not undergone much improvement. Indeed, man is still very much an unfinished type, who clearly has actualized only a small fraction of his human potentialities. In addition, his genetic deterioration is being rendered probable by his social set-up, and definitely being promoted by atomic fallout. Furthermore, his economic, technical and cultural progress is threatened by the high rate of increase of world population.

The obverse of man's actual and potential further defectiveness is the vast extent of his possible future improvement. To effect this, he must first of all check the processes making for genetic deterioration. This means reducing man-made radiation to a minimum, discouraging genetically defective or inferior types from breeding, reducing human over-multiplication in general and the high differential fertility of various regions, nations and classes in particular. Then he can proceed to the much more important task of positive improvement. In the not too distant future the fuller realization of possibilities will inevitably come to provide the main motive for man's overall efforts; and a Science of Evolutionary Possibilities, which to-day is merely adumbrated, will provide a firm basis for these efforts. Eugenics can make an important contribution to man's further evolution: but it can only do so if it considers itself as one branch of that new nascent science, and fearlessly explores all the possibilities that are open to it.

Man, let me repeat, is not a biological but a psychosocial organism. As such, he possesses a new mechanism of transmission and transformation based on the cumulative handing on of experience, ideas and attitudes. To obtain eugenic improvement, we shall need not only an understanding of what kind of selection operates in the psychosocial process, not only new scientific knowledge and new techniques in the field of human genetics and reproduction but new ideas and attitudes about reproduction and parenthood in particular and human destiny in general. One of those new ideas will be the moral imperative of Eugenics.

Chapter 1: Historicism And The Myth Of Destiny

It is widely believed that a truly scientific or philosophical attitude towards politics, and a deeper understanding of social life in general, must be based upon a contemplation and interpretation of human history. While the ordinary man takes the setting of his life and the importance of his personal experiences and petty struggles for granted, it is said that the social scientist or philosopher has to survey things from a higher plane. He sees the individual as a pawn, as a somewhat insignificant instrument in the general development of mankind. And he finds that the really important actors on the Stage of History are either the Great Nations and their Great Leaders, or perhaps the Great Classes, or the Great Ideas. However this may be, he will try to understand the meaning of the play which is performed on the Historical Stage; he will try to understand the laws of historical development. If he succeeds in this, he will, of course, be able to predict future developments. He might then put politics upon a solid basis, and give us practical advice by telling us which political actions are likely to succeed or likely to fail.

This is a brief description of an attitude which I call historicism. It is an old idea, or rather, a loosely connected set of ideas which have become, unfortunately, so much a part of our spiritual atmosphere that they are usually taken for granted, and hardly ever questioned.

I have tried elsewhere to show that the historicist approach to the social sciences gives poor results. I have also tried to outline a method which, I believe, would yield better results.

But if historicism is a faulty method that produces worthless results, then it may be useful to see how it originated, and how it succeeded in entrenching itself so successfully. An historical sketch undertaken with this aim can, at the same time, serve to analyse the variety of ideas which have gradually accumulated around the central historicist doctrine—the doctrine that history is controlled by specific historical or evolutionary laws whose discovery would enable us to prophesy the destiny of man.

Historicism, which I have so far characterized only in a rather abstract way, can be well illustrated by one of the simplest and oldest of its forms, the doctrine of the chosen people. This doctrine is one of the attempts to make history understandable by a theistic interpretation, i.e. by recognizing God as the author of the play performed on the Historical Stage. The theory of the chosen people, more specifically, assumes that God has chosen one people to function as the selected instrument of His will, and that this people will inherit the earth.

In this doctrine, the law of historical development is laid down by the Will of God. This is the specific difference which distinguishes the theistic form from other forms of historicism. A naturalistic historicism, for instance, might treat the developmental law as a law of nature; a spiritual historicism would treat it as a law of spiritual development; an economic historicism, again, as a law of economic development. Theistic historicism shares with these other forms the doctrine that there are specific historical laws which can be discovered, and upon which predictions regarding the future of mankind can be based.

There is no doubt that the doctrine of the chosen people grew out of the tribal form of social life. Tribalism, i.e. the emphasis on the supreme importance of the tribe without which the individual is nothing at all, is an element which we shall find in many forms of historicist theories. Other forms which are no longer tribalist may still retain an element of collectivism [1] ; they may still emphasize the significance of some group or collective—for example, a class— without which the individual is nothing at all. Another aspect of the doctrine of the chosen people is the remoteness of what it proffers as the end of history. For although it may describe this end with some degree of definiteness, we have to go a long way before we reach it. And the way is not only long, but winding, leading up and down, right and left. Accordingly, it will be possible to bring every conceivable historical event well within the scheme of the interpretation. No conceivable experience can refute it. [2] But to those who believe in it, it gives certainty regarding the ultimate outcome of human history.

A criticism of the theistic interpretation of history will be attempted in the last chapter of this book, where it will also be shown that some of the greatest Christian thinkers have repudiated this theory as idolatry. An attack upon this form of historicism should therefore not be interpreted as an attack upon religion. In the present chapter, the doctrine of the chosen people serves only as an illustration. Its value as such can be seen from the fact that its chief characteristics [3] are shared by the two most important modern versions of historicism, whose analysis will form the major part of this book—the historical philosophy of racialism or fascism on the one (the right) hand and the Marxian historical philosophy on the other (the left). For the chosen people racialism substitutes the chosen race (of Gobineau’s choice), selected as the instrument of destiny, ultimately to inherit the earth. Marx’s historical philosophy substitutes for it the chosen class, the instrument for the creation of the classless society, and at the same time, the class destined to inherit the earth. Both theories base their historical forecasts on an interpretation of history which leads to the discovery of a law of its development. In the case of racialism, this is thought of as a kind of natural law; the biological superiority of the blood of the chosen race explains the course of history, past, present, and future; it is nothing but the struggle of races for mastery. In the case of Marx’s philosophy of history, the law is economic; all history has to be interpreted as a struggle of classes for economic supremacy. The historicist character of these two movements makes our investigation topical. We shall return to them in later parts of this book. Each of them goes back directly to the philosophy of Hegel. We must, therefore, deal with that philosophy as well. And since Hegel [4] in the main follows certain ancient philosophers, it will be necessary to discuss the theories of Heraclitus, Plato and Aristotle, before returning to the more modern forms of historicism.

-- The Open Society and Its Enemies, by Karl R. Popper

* * *

In the twenty-five years since my previous lecture, many events have occurred, and many discoveries have been made with a bearing on eugenics. Events such as the explosion of atomic and nuclear bombs, the equally sinister "population explosion," the reductio ad horrendum of racism by Nazi Germany, and the introduction of artificial insemination for animals and human beings, sometimes with the use of deep-frozen sperm; scientific discoveries such as that of DNA as the essential basis for heredity and evolution, of subgenic organization, of the widespread existence of balanced polymorphic genetic systems, and of the intensity and efficacy of selection in nature; the realization that the entities which evolve are populations of phenotypes, with consequent emphasis on population genetics on the one hand, and on the interaction between genotype and environment on the other; and finally the recognition that adaptation and biological improvement are universal phenomena in life.

I do not propose to discuss these changes and discoveries now, but shall plunge directly into my subject -- Eugenics in Evolutionary Perspective. I chose this title because I am sure that a proper understanding of the evolutionary process and of man's place and role in it is necessary for any adequate or satisfying view of human destiny; and eugenics must obviously play an important part in enabling man to fulfil that destiny.

As I have set forth at greater length elsewhere, in the hundred years since the publication of the Origin of Species there has been a "knowledge explosion" unparalleled in all previous history. It has led to an accelerated expansion of ideas, not only in the natural sciences but also in the humanistic fields of history, archaeology, and social and cultural development, and its effects on our thinking have been especially violent, not to say revolutionary, during the quarter of a century since my previous Galton Lecture. It has led to a new picture of man's relations with his own nature and with the rest of the universe, and indeed to a new and unified vision of reality, both fuller and truer than any of the insights of the past. In the light of this new vision the whole of reality is seen as a single process of evolution. For evolution can properly be defined as a natural process in time, self-varying and self-transforming and generating increasing complexity and variety during its transformations; and this is precisely what has been going on for all time in all the universe. It operates everywhere and in all periods, but is divisible into a series of three sectors or successive phases, the inorganic or cosmic, the organic or biological, and the human or psychosocial, each based on and growing out of its predecessor. Each phase operates by a different main mechanism, has a different scale and a different tempo of change, and produces a different type of results.

Between the separate phases, the evolutionary process has to cross a critical threshold, passing from an old to a new state, as when water passes from the solid to the liquid state at the critical temperature-threshold of 0° C and from liquid to gaseous at that of 100° C.

The critical threshold between the inorganic and the biological phase was crossed when matter and the organisms built from it became self-reproducing, that between the biological and the psychosocial when mind and the organizations generated by it became self-reproducing in their turn.

The cosmic phase operates by random interaction, primarily physical but to a small degree chemical. Its quantitative scale is unbelievably vast both in space and time. Its visible dimensions exceed 1,000 million light-years (10[22]km), its distances are measured by units of thousands of light-years (nearly 10[16]km), the numbers of its visible galaxies exceed 100 million (10[8]) and those of its stars run into thousands of millions of millions (10[15]). It has operated in its present form for at least 6,000 million years, possibly much longer. Its tempo of major change is unbelievably slow, to be measured by 1,000-million-year periods. According to the physicists, its overall trend, in accord with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, is entropic, tending towards a decrease in organization and to ultimate frozen immobility; and its products reach only a very low level of organization -- photons, subatomic particles, atoms, and simple inorganic compounds at one end of its size-scale, nebulae, stars and occasional planetary systems at the other.

The biological phase operates primarily by the teleonomic or ordering process of natural selection, which canalizes random variation into non-random directions of change. Its tempo of major change is somewhat less slow, measured by 100-million- instead of 1,000-million-year units of time. Its overall trend, kept going of course by solar energy, is anti-entropic, towards an increase in the amount and quality of adaptive organization, and marked by the growing importance of awareness as mediated by brains. And its results are organisms -- organisms of an astonishing efficiency, complexity, and variety, almost inconceivably so until one recalls R. A. Fisher's profound paradox, that natural selection plus time is a mechanism for generating an exceedingly high degree of improbability.

In the course of biological evolution, three sub-processes are at work. The first (cladogenesis, or branching evolution) leads to divergence and greater variety; the second (anagenesis, or upward evolution) leads to improvement of all sorts, from detailed adaptations to specializations, from the greater efficiency of some major function like digestion to overall advance in general organization; the third is stasigenesis or stabilized limitation of evolution. This occurs when specialization for a particular way of life reaches a dead end as with horses, or efficiency of function attains a maximum as with hawks' vision, or an ancient type of organization persists as a living fossil like the lungfish or the tuatara.

Major advance or biological progress is always by a succession of dominant types, each step achieved by a rare breakthrough from some established type of organization to a new and more effective one, as from the amphibian to true dry-land reptilian type, or from the coldblooded egg-laying reptile to the warm-blooded self-regulating mammal with intra-uterine development. The new dominant type multiplies at the expense of the old, which may become extinct (as did the jawless fish) or may persist in reduced numbers (as did the reptiles.)

The psychosocial phase, the latest of which we have any knowledge (though elsewhere in the universe there may have been a breakthrough to some new phase as unimaginable to us as the psychosocial phase would have been to even the most advanced Pliocene primate), is based on a self-reproducing and self-varying system of cumulative transmission of experience and culture, operating by mechanisms of psychological and social selection which we have not as yet adequately defined or analysed. Spatially it is very limited; we know of it only on this earth, and in any case it must be restricted to the surface of a small minority of planets in the small minority of stars possessing planetary systems. On our planet it is at the very beginning of its course, having begun less than one million years ago. However, its tempo is not only much faster than that of biological evolution, but manifests a new phenomenon, in the shape of a marked acceleration. Its overall trend is highly antientropic, and is characterized by a sharp increase in the operative significance of exceptional individuals and in the importance of true purpose and conscious evaluation based on reason and imagination, as against the automatic differential elimination of random variants.

The most significant element in that trend has been the growth and improved organization of tested and established knowledge. And its results are psychologically (mentally) generated organizations even more astonishingly varied and complex than biological organisms -- machines, concepts, cooking, mass communications, cities, philosophies, superstitions, propaganda, armies and navies, personalities, legal systems, works of art, political and economic systems, entertainments, slavery, scientific theories, hospitals, moral codes, prisons, myths, languages, torture, games and sports, religions, record and history, poetry, civil services, marriage systems, initiation rituals, agriculture, drama, social hierarchies, schools and universities. Accordingly evolution in the human phase is no longer purely biological, based on changes in the material system of genetic transmission, but primarily cultural, based on changes in the psychosocial system of ideological and cultural transmission.

In the psychosocial phase of evolution the same three sub-processes operating in the biological phase are still at work -- cladogenesis, operating to generate difference and variety within and between cultures; anagenesis, operating to produce improvement in detailed technological methods, in economic and political machinery, in administrative and educational systems, in scientific thinking and creative expression, in moral tone and religious attitude, in social and international organization; and stasigenesis, operating to limit progress and to keep old systems and attitudes, including even outworn superstitions, persisting alongside of or actually within more advanced social and intellectual systems. But there is an additional fourth sub-process, that of convergence (or at least anti-divergence), operating by diffusion -- diffusion of ideas and techniques between individuals, communities, cultures and regions. This is tending to give unity to the world: but we must see to it that it does not also impose uniformity and destroy desirable variety.

As in the biological phase, major advance in the human phase is brought about by a succession of generally or locally dominant types. These, however, are not types of organism, but of cultural and ideological organization. Monotheism as against polytheism, for instance; or in the political sphere, the beginning of one-world internationalism as against competitive multinationalism. Or again, science as against magic, democracy as against tyranny, planning as against laissez-faire, tolerance as against intolerance, freedom of opinion and expression as against authoritarian dogma and repression.

Not only does the succession of dominant types bring about progress or advance in organization within each of the three main evolutionary phases, but it also operates, though on a grander and more decisive scale, in the evolutionary process as a whole. A biological organism possesses a higher degree of organization than any inorganic system; as soon as living organisms were produced, they became the major dominant type of organization on earth, and the course of evolution became predominantly biological and only secondarily inorganic. Similarly a psychosocial system possesses a higher degree of organization than any biological organism: accordingly man at once became the new major dominant type on earth, and the course of evolution became predominantly cultural and only secondarily biological, with inorganic methods quite subordinate.

The evolutionary perspective includes the broad background of the cosmic past. Now against this background we must face the problems of the present and the challenge of the future. Let me begin by reiterating that man is an exceedingly recent phenomenon. The earliest creatures which can properly be called men, though they must be assigned to different genera from ourselves, date from less than two million years ago, and our own species, Homo sapiens, from much less than half a million years. Man began to put his toe tentatively across the critical threshold leading towards evolutionary dominance perhaps a quarter of a million years ago, but took tens of thousands of years to cross it, emerging as a dominant type only during the last main glaciation, probably later than 100,000 B.C., but not becoming fully dominant until the discovery of agriculture and stock-breeding well under 10,000 years ago, and overwhelmingly so with the invention of machines and writing and organized civilization a bare five millennia before the present day, when his dominance has become so hubristic as to threaten his own future.

All new dominant types begin their career in a crude and imperfect form, which then needs drastic polishing and improvement before it can reveal its full potentialities and achieve full evolutionary success. Man is no exception to this rule. He is not merely exceedingly young; he is also exceedingly imperfect, an unfinished and often botched product of evolutionary improvisation. Teilhard de Chardin has called the transformation of an anthropoid into a man hominisation: it might be more accurately, though more clumsily, termed psychosocialisation. But whatever we call it, the process of hominisation is very far from complete, the serious study of its course, its mechanisms and its techniques has scarcely started, and only a fraction of its potential results have been realized. Man, in fact, is in urgent need of further improvement.

This is where eugenics comes into the picture. For though the psychosocial system in and by which man carries on his existence could obviously be enormously improved with great benefit to its members, the same is also true for his genetic outfit.

Severe and primarily genetic disabilities like haemophilia, colour-blindness, mongolism, some kinds of sexual deviation, much mental defect, sickle-cell anaemia, some forms of dwarfism, and Huntington's chorea are the source of much individual distress, and their reduction would remove a considerable burden from suffering humanity. But these are occasional abnormalities. Quantitatively their total effect is insignificant in comparison with the massive imperfection of man as a species, and their reduction appears as a minor operation in comparison with the large-scale positive possibilities of all-round general improvement.

Take first the problem of intelligence. It is to man's higher level of intelligence that he owes his evolutionary dominance; and yet how low that level still remains! It is now well established that the human I.Q., when properly assayed, is largely a measure of genetic endowment. Consider the difference in brain-power between the hordes of average men and women with I.Q.'s around 100 and the meagre company of Terman's so-called geniuses with I.Q.'s of 160 or over, and the much rarer true geniuses like Newton and Darwin, Tolstoy and Shakespeare, Goya and Michelangelo, Hammurabi and Confucius; and then reflect that, since the frequency curve for intelligence is approximately symmetrical, there are as many stupider people with I.Q.'s below 100 as there are abler ones with I.Q.'s above it.

Scientifically, there is no method that can apportion group differences in this way, no empirical analysis that might assign IQ differences between racial groups to one or another source, much less come up with a meaningful balance between the two.

There is not a single example of a group difference in any complex human behavioral trait that has been shown to be environmental or genetic, in any proportion, on the basis of scientific evidence. Ethically, in the absence of a valid scientific methodology, speculations about innate differences between the complex behavior of groups remain just that, inseparable from the legacy of unsupported views about race and behavior that are as old as human history. The scientific futility and dubious ethical status of the enterprise are two sides of the same coin.

-- There’s still no good reason to believe black-white IQ differences are due to genes: Our response to criticisms, by Eric Turkheimer, Kathryn Paige Harden, and Richard E. Nisbett

Recollect also that the great and striking advances in human affairs, as much in creative art and political and military leadership as in scientific discovery and invention, are primarily due to a few exceptionally gifted individuals. Remember that on the established principles of genetics a small raising of average capacity would of necessity result in an upward shifting of the entire frequency curve, and therefore a considerable increase in the absolute numbers of such highly intelligent and well-endowed human beings that form the uppermost section of the curve (as well as a decrease in the numbers of highly stupid and feebly endowed individuals at the lower end).

Reflect further on the fact, originally pointed out by Galton, that there is already a shortage of brains capable of dealing with the complexities of modern administration, technology and planning, and that with the inevitable increase of our social and technical complexity, the greater will that shortage become. It is thus clear that for any major advance in national and international efficiency we cannot depend on haphazard tinkering with social or political symptoms or ad hoc patching up of the world's political machinery, or even on improving general education, but must rely increasingly on raising the genetic level of man's intellectual and practical abilities. As I shall later point out, artificial insemination by selected donors could bring about such a result in practice.

The same applies everywhere in the psychosocial process. For more and better scientists, we need the raising of the genetic level of exploratory curiosity or whatever it is that underlies single-minded investigation of the unknown and the discovery of novel facts and ideas; for more and better artists and writers, we need the raising of the genetic level for disciplined creative imagination; for more and better statesmen, that of the capacity to see social and political situations as wholes, to take long-term and total instead of only short-term and partial views; for more and better technologists and engineers, that of the passion and capacity to understand how things work and to make them work more efficiently; for more and better saints and moral leaders, that of disciplined valuation, of devotion and duty, and of the capacity to love; and for more and better leaders of thought and guides of action we need a raising of the capacity of man's vision and imagination, to form a comprehensive picture, at once reverent, assured and unafraid, of nature and man's relations with it.

These facts and ideas have an important bearing on the so-called race question and the problem of racial equality. I should rather say racial inequality, for up till quite recently the naive belief in the natural inequality of races and people in general, and the inherent superiority of one's own race or people in particular, has almost universally prevailed.

To demonstrate the way in which this point of view permeated even nineteenth-century scientific thought, it is worth recalling that it was largely subscribed to by Darwin in his comments on the Fuegians in the Voyage of the Beagle, and in more general but more guarded terms in the Descent of Man: and Galton himself, against a similar background of travels among backward tribes and on the basis of his own rather curious method of assessment, concluded that different races had achieved different genetic standards, so that, for instance, "the average standard of the Negro race is two grades below our own." This type of belief, after being given a pseudoscientific backing by non-biological theoreticians like Gobineau and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, was used to justify the Nazis' "Nordic" claims to world domination and their horrible campaign for the extermination of the "inferior, non-Aryan race" of Jews, and is still employed with support from Holy Writ and the majority of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa, to sanction Verwoerd's denial of full human rights to non-whites.

Later investigation has conclusively demonstrated first, that there is no such thing as a "pure race." Secondly, that the obvious differences in level of achievement between different peoples and ethnic groups are primarily cultural, due to differences not in genetic equipment but in historical and environmental opportunity. And thirdly, that when the potentialities of intelligence of two major "races" or ethnic groups, such as whites and negroes or Europeans and Indians, are assessed as scientifically as possible, the frequency curves for the two groups overlap over almost the whole of their extent, so that approximately half the population of either group is genetically stupider (has a lower genetic I.Q.) than the genetically more intelligent half of the other. There are thus large differences in genetic mental endowment within single racial groups, but minimal ones between different racial groups.

Partly as a result of such studies, but also of the prevalent environmentalist views of Marxist and Western liberal thought, an anti-genetic view has recently developed about race. It is claimed that though ethnic groups obviously differ in physical characters, and that some of them, like pigmentation, nasal form, and number of sweatglands, were originally adaptive, they do not (and sometimes even that they cannot) differ in psychological or mental characters such as intelligence, imagination, or even temperament. [ii]

Against this new pseudo-scientific racial naivete, we must set the following scientific facts and principles. First, it is clear that the major human races originated as geographical subspecies of Homo sapiens, in adaptation to the very different environments to which they have become restricted. Later, of course, expansion and migration reversed the process of differentiation and led to an increasing degree of convergence by crossing, though considerable genetic differentiation remains. Secondly, as Professor Muller has pointed out, it is theoretically inconceivable that such marked physical differences as still persist between the main racial groups should not be accompanied by genetic differences in temperament and mental capacities, possibly of considerable extent. Finally, as previously explained, advance in cultural evolution is largely and increasingly dependent on exceptionally well-endowed individuals. Thus two racial groups might overlap over almost the whole range of genetic capacity, and yet one might be capable of considerably higher achievement, not merely because of better environmental and historical opportunity, but because it contained say 2 instead of 1 per cent of exceptionally gifted men and women. So far as I know, proper scientific research on this subject has never been carried out, and possibly our present methods of investigation are not adequate for doing so, but the principle is theoretically clear and is of vital practical importance. [iii]

This does not imply any belief in crude racism, with its unscientific ascription of natural and permanent superiority or inferiority to entire races. As I have just pointed out, approximately half of any large ethnic group, however superior its self-image may be, is in point of fact genetically inferior to half of the rival ethnic group with which it happens to be in social or economic competition and which it too often stigmatizes as permanently and inherently lower. Furthermore, practical experience demonstrates that every so-called race, however underdeveloped its economic and social system may happen to be, contains a vast reservoir of untapped talent, only waiting to be elicited by a combination of challenging opportunity, sound educational methods, and efficient special training. I recently attended an admirable symposium on nutrition in Nigeria where the scientific quality of the African contributions was every whit as high as that of the whites; and African politicians can be just as statesmanlike (and also just as unscrupulously efficient in the political game) as their European or American counterparts.

The basic fact about the races of mankind is their almost total overlap in genetic potentialities. But the most significant fact for eugenic advance is the large difference in achievement made possible by a small increase in the number of exceptional individuals.

The evolutionary biologist can point out to the social scientist and the politician that this importance of the exceptional individual for psychosocial advance is merely an enhancement of a long-established evolutionary trend. Exceptional individuals can be important for biological improvement in mammals, in birds, and possibly even in insects. New food-traditions in Japanese monkeys are established by disobedient young individuals. The utilization of milk-bottles as a new source of food by blue tits was due to the activities of a few exceptional tit geniuses in a few widely separate localities. All male satin bowerbirds construct bowers and assemble collections of stimulating bright objects at them, but only a minority deliberately paint their bowers with a mixture of berries, charcoal and saliva, and only a still smaller minority indulge the species' natural preference for blue objects by deliberately stealing bluebags to add to their display collection. And there is some evidence that even in ants, those prototypes of rigidly instinctive behaviour, a few workers are exceptionally well-endowed with the exploratory urge, and play a special role in discovering new sources of food for the colony.

But I must return to man as a species. The human species is in desperate need of genetic improvement if the whole process of psychosocial evolution which it has set in train is not to get bogged down in unplanned disorder, negated by over-multiplication, clogged up by mere complexity, or even blown to pieces by obsessional stupidity. Luckily it not only must but can be improved. It can be improved by the same type of method that has secured the improvement of life in general -- from protozoan to protovertebrate, from protovertebrate to primate, from primate to human being -- the method of multi-purpose selection directed towards greater achievement in the prevailing conditions of life.

On the other hand, it cannot be improved by applying the methods of the professional stockbreeder. Indeed the whole discussion of eugenics has been bedevilled by the false analogy between artificial and natural selection. Artificial selection is intensive special-purpose selection, aimed at producing a particular excellence, whether in milk-yield in cattle, speed in race-horses or a fancy image in dogs. It produces a number of specialized pure breeds, each with a markedly lower variance than the parent species. Darwin rightly drew heavily on its results in order to demonstrate the efficacy of selection in general. But since he never occupied himself seriously with eugenics he did not point out the irrelevance of stock-breeding methods to human improvement. In fact, they are not only irrelevant, but would be disastrous. Man owes much of his evolutionary success to his unique variability. Any attempt to improve the human species must aim at retaining this fruitful diversity, while at the same time raising the level of excellence in all its desirable components, and remembering that the selectively evolved characters of organisms are always the results of compromise between different types of advantage, or between advantage and disadvantage.

Natural selection is something quite different. To start with, it is a shorthand metaphorical term coined by Darwin to denote the teleonomic or directive agencies affecting the process of evolution in nature, and operating through the differential survival and reproduction of genetical variants. It may operate between conspecific individuals, between conspecific populations, between related species, between higher taxa such as genera and families, or between still larger groups of different organizational type, such as Orders and Classes. It may also operate between predator and prey, between parasite and host, and between different synergic assemblages of species, such as symbiotic partnerships and ecological communities. It is in fact universal in its occurrence, though multiform in its mode of action.

Some over-enthusiastic geneticists appear to think that natural selection acts directly on the organism's genetic outfit or genotype. This is not so. Natural selection exerts its effects on animals and plants as working mechanisms: it can operate only on phenotypes. Its evolutionary action in transforming the genetic outfit of a species is indirect, and depends on the simple fact pointed out by Darwin in the Origin that much variation is heritable -- in modern terms, that there is a high degree of correlation between phenotypic and genotypic variance. The correlation, however, is never complete, and there are many cases where it is impossible without experimental analysis to determine whether a variant is modificational, due to alteration in the environment, or mutational, due to alteration in the genetic outfit. In certain cases, environmental treatment will produce so-called phenocopies which are indistinguishable from mutants in their visible appearance.

This last fact has led Waddington to an important discovery -- the fact that an apparently Lamarckian mode of evolutionary transformation can be precisely simulated by what he calls genetic assimilation. To take an actual example, the rearing of fruitfly larvae on highly saline media produces a hypertrophy of their salt-excreting glands through direct modification. But if selection is practised by breeding from those individuals which show the maximum hypertrophy of their glands, then after some ten or twelve generations, individuals with somewhat hypertrophied glands appear even in cultures on non-saline media. The species has a genetic predisposition, doubtless brought by selection in the past, to react to saline conditions by glandular hypertrophy. The action of the major genes concerned in reactions of this sort can be enhanced (or inhibited) by so-called modifying genes of minor effect. Selection has simply amassed in the genetic outfit an array of such minor enhancing genes strong enough to produce glandular hypertrophy even in the absence of any environmental stimulus. It is only pseudo-Lamarckism, but no less important for that -- a significant addition to the theoretical armoury of evolutionary science.

I repeat that the most important effect achieved by natural selection is biological improvement. As G. G. Simpson reminds us, it does so opportunistically, making use of whatever new combination of existing mutant genes, or less frequently of whatever new mutations, happens to confer differential survival value on its possessors. We know of numerous cases where phenotypically identical and adaptive transformations have been produced by different genes or gene-combinations.

Here I must digress a moment to discuss the concept of evolutionary fitness. The biological avant garde has chosen to define fitness as "net reproductive advantage," to use the actual words employed by Professor Medawar in his Reith Lectures on The Future of Man. Any strain of animal, plant, or man which leaves slightly more descendants capable of reproducing themselves than another, is then defined as "fitter." This I believe to be an unscientific and misleading definition. It disregards all scientific conventions as to priority, for it bears no resemblance to what Spencer implied or intended by his famous phrase the survival of the fittest. [iv] It is also nonsensical in every context save the limited field of population genetics. In biology, fitness must be defined, as Darwin did with improvement, "in relation to the conditions of life" -- in other words, in the context of the general evolutionary situation. I shall call it evolutionary fitness, in contradistinction to the purely reproductive fitness of the evangelists of geneticism, which I prefer to designate by the descriptive label of net or differential reproductive advantage.

Meanwhile, I have a strong suspicion that the genetical avant garde of to-day will become the rearguard of tomorrow. In my own active career I have seen a reversal of this sort in relation to natural selection and adaptation. During the first two decades of this century the biological avant garde dismissed topics such as cryptic or mimetic coloration, and indeed most discussion of adaptation, as mere "armchair speculation," and played down the role of natural selection in evolution, as against that of large and random mutation. Bateson's enthusiasm rebounded from his early protest against speculative phylogeny into the far more speculative suggestion made ex cathedra at a British Association meeting, that all evolution, whether of higher from lower, or of diversity from uniformity, had been brought about by loss mutations; and the great T. H. Morgan once permitted himself to state in print that, if natural selection had never operated, we should possess all the organisms that now exist and a great number of other types as well! This anti-selectionist avant garde of fifty years back has now come over en masse into the selectionist camp, leaving only a few retreating stragglers to deliver some rather ineffective parthian shots at their opponents.

Natural selection is a teleonomic or directional agency. It utilizes the inherent genetic variability of organisms provided by the raw material of random mutation and chance recombination, and it operates by the simple mechanism of differential reproductive advantage. But on the evolutionary time-scale it produces biological improvement, resulting in a higher total and especially a higher upper level of evolutionary fitness, involving greater functional efficiency, higher degrees of organization, more effective adaptation, better self-regulating capacity, and finally more mind -- in other words an enrichment of qualitative awareness coupled with more flexible behaviour.

Man almost certainly has the largest reservoir of genetical variance of any natural species: selection for the differential reproduction of desirable permutations and combinations of the elements of this huge variance could undoubtedly bring about radical improvement in the human organism, just as it has in pre-human types. But the agency of human transformation cannot be the blind and automatic natural selection of the pre-human sector. That, as I have already stressed, has been relegated to a subsidiary role in the human phase of evolution. Some form of psychosocial selection is needed, a selection as non-natural as are most human activities, such as wearing clothes, going to war, cooking food, or employing arbitrary systems of communication. To be effective, such "non-natural" selection must be conscious, purposeful and planned. And since the tempo of cultural evolution is many thousands of times faster than that of biological transformation, it must operate at a far higher speed than natural selection if it is to prevent disaster, let alone produce improvement.

Luckily there is to-day at least the possibility of meeting both these prerequisites: we now possess an accumulation of established knowledge and an array of tested methods which could make intelligent, scientific and purposeful planning possible. And we are in the process of discovering new techniques which could raise the effective speed of the selective process to a new order of magnitude. The relevant new knowledge mainly concerns the various aspects of the evolutionary process -- the fact that there are no absolutes or all-or-nothing effects in evolution and that all organisms and all their phenotypic characters represent a compromise or balance between competing advantages and disadvantages; the effect of selection on populations in different environmental conditions; the origin of adaptation; and the general improvement of different evolutionary lines in relation to the conditions of their life. The notable new techniques include effective methods of birth-control, the successful development of grafted fertilized ova in new host-mothers, artificial insemination, and the conservation of function in deep-frozen gametes.

We must first keep in mind the elementary but often neglected fact that the characters of organisms which make for evolutionary success or failure, are not inherited as such. On the contrary, they develop anew in each individual, and are always the resultant of an interaction between genetic determination and environmental modification. Biologists are often asked whether heredity or environment is the more important. It cannot be too often emphasized that the question should never be asked. It is as logically improper to ask a biologist to answer it as it is for a prosecuting counsel to ask a defendant when he stopped beating his wife. It is the phenotype which is biologically significant and the phenotype is a resultant produced by the complex interaction of hereditary and environmental factors. Eugenics, in common with evolutionary biology in general, needs this phenotypic approach.

Man's evolution occurs on two different levels and by two distinct methods, the genetic, based on the transmission and variation of genes and gene-combinations, and the psychosocial or cultural, based on the transmission and variation of knowledge and ideas.

Professor Medawar, in his Reith Lectures on The Future of Man, while admitting in his final chapter that man possesses "a new, nongenetical, system of heredity and evolution" (p. 88), claims on p. 41 that this is "a new kind of biological evolution (I emphasize, a biological evolution)." I must insist that this is incorrect. The psychosocial process -- in other words, evolving man -- is a new state of evolution, a new phase of the cosmic process, as radically different from the pre-human biological phase as that is from the inorganic or pre-biological phase; and this fact has important implications for eugenics.

An equally elementary but again often neglected fact is that organisms are not significant -- in plain words, are meaningless -

except in relation to their environment. A fish is not a thing-in-itself: it is a type of organism evolved in relation to an active life in large or medium-sized bodies of water. A cactus has biological significance only in relation to an arid habitat, a woodpecker only in relation to an arboreal one. Man, however, is in a unique situation. He must live not only in relation with the physicochemical and biological environment provided by nature, but with the psychosocial environment of material and mental habitats which he has himself created.

Man's psychosocial environment includes his beliefs and purposes, his ideals and his aims: these are concerned with what we may call the habitat of the future, and help to determine the direction of his further evolution. All evolution is directional and therefore relative. But whereas the direction of biological evolution is related to the continuing improvement of organisms in relation to their conditions of life, human evolution is related to the improvement of the entire psychosocial process, including the human organism, in relation to man's purposes and beliefs, long-term as well as short-term. Only in so far as those purposes and beliefs are grounded on scientific and tested knowledge, will they serve to steer human evolution in a desirable direction. In brief, biological evolution is given direction by the blind and automatic agency of natural selection operating through material mechanisms, human evolution by the agency of psychosocial guidance operating with the aid of mental awareness, notably the mechanisms of reason and imagination.

To be effective, such awareness must clearly be concerned with man's environmental situation as well as his genetic equipment. In my first Galton Lecture, I pointed out the desirability of eugenists relating their policies to the social environment. To-day I would go further, and stress the need for planning the environment in such a way as will promote our eugenic aims. By 1936, it was already clear that the net effect of present-day social policies could not be eugenic, and was in all probability dysgenic. But, as Muller has demonstrated, this was not always so. In that long period of human history during which our evolving and expanding hominid ancestors lived in small and tightly knit groups competing for territorial and technological success, the social organization promoted selection for intelligent exploration of possibilities, devotion and cooperative altruism: the cultural and the genetic systems reinforced each other. It was only much later, with the growth of bigger social units of highly organized civilizations based on status and class differentials, that the two became antagonistic; the sign of genetic transformation changed from positive to negative and definite genetic improvement and advance began to halt, and gave way to the possibility and later the probability of genetic regression and degeneration.

This probability has been very much heightened during the last century, partly by the differential multiplication of economically less favoured classes and groups in many parts of the world, partly by the progress of medicine and public health, which has permitted numbers of genetically defective human beings to survive and reproduce; and to-day it has been converted into a certainty by the series of atomic and nuclear explosions which have been set off since the end of the last war. There is still dispute as to the degree of damage this has done to man's genetic equipment. There can be no dispute as to the fact of damage: any addition to man's load of mutations can only be deleterious, even if some of them may possibly come to be utilized in neutral or even favourable new gene-combinations.

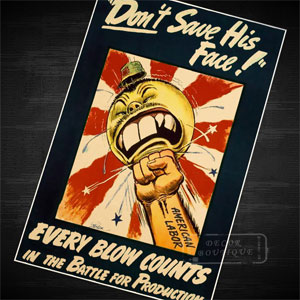

[American Labor] Don't Save His Face! Every Blow Counts in the Battle For Production

[M]edicine and public health ... has permitted numbers of genetically defective human beings to survive and reproduce; and today it has been converted into a certainty by the series of atomic and nuclear explosions which have been set off since the end of the last war. There is still dispute as to the degree of damage this has done to man's genetic equipment. There can be no dispute as to the fact of damage: any addition to man's load of mutations can only be deleterious, even if some of them may possibly come to be utilized in neutral or even favourable new gene-combinations.

-- Eugenics in Evolutionary Perspective, by Sir Julian Huxley, M.A., D.Sc., F.R.S.