6. The Worst Trek of All A meeting with the robber Khampas — Hunger and cold: and an unexpected Christmas present — The safe-conduct — Prayer-flags on the Pilgrims’ Way — A convict as fellow-lodger — We approach Lhasa. We had been some time on the way when a man came towards us wearing clothes which struck us as unusual. He spoke a dialect different from that of the local nomads. He asked us curiously whence? and whither? and we told him our pilgrimage story. He left us unmolested and went on his way. It was clear to us that we had made the acquaintance of our first Khampa.

A few hours later we saw in the distance two men on small ponies, wearing the same sort of clothes. We slowly began to feel uncomfortable and went on without waiting for them.

Long after dark we came across a tent. Here we were lucky as it was inhabited by a pleasant nomad family, who hospitably invited us to come in and gave us a special fireplace for ourselves.

In the evening we got talking about the robbers. They were, it seems, a regular plague. Our host had lived long enough in the district to make an epic about them. He proudly showed us a Mannlicher rifle for which he had paid a fortune to a Khampa — five hundred sheep, no less! But the robber bands in the neighbourhood considered this payment as a sort of tribute and had left him in peace ever since.

He told us something about the life of the robbers. They lived in groups in three or four tents which serve as headquarters for their campaigns. These are conducted as follows: heavily armed with rifles and swords they force their way into a nomad’s tent and insist on hospitable entertainment on the most lavish scale available. The nomad in terror brings out everything he has. The Khampas fill their bellies and their pockets and taking a few cattle with them, for good measure, disappear into the wide-open spaces. They repeat the performance at another tent every day till the whole region has been skinned. Then they move their headquarters and begin again somewhere else. The nomads, who have no arms, resign themselves to their fate, and the Government is powerless to protect them in these remote regions. However, if once in a way a district officer gets the better of these footpads in a skirmish, he is not the loser by it for he has a right to all the booty. Savage punishment is meted out to the evildoers, who normally have their arms hacked off. But this does not cure the Khampas of their lawlessness. Stories were told of the cruelty with which they sometimes put their victims to death. They go so far as to slaughter pilgrims and wandering monks and nuns. A disturbing conversation for us! What would we not have given to be able to buy our host’s Mannlicher! But we had no money and not even the most primitive weapons. The tent-poles we carried did not impress even the sheep-dogs. Next morning we went on our way, not without misgivings, which increased when we saw a man with a gun, who seemed to be stalking us from the hillside. Nevertheless we kept straight on our course, and the man eventually disappeared. In the evening we found more tents — first a single one and then a cluster of others.

We called to the people in the first tent. A family of nomads came out. They refused with expressions of horror to admit us and pointed distractedly to the other tents. There was nothing for it but to go on. We were no little surprised to receive a friendly welcome at the next tent. Everyone came out. They fingered our things and helped us to unload — a thing which no nomads had ever done — and suddenly it dawned on us that they were Khampas. We had walked like mice into the trap. The inhabitants of the tent were two men, a woman and a half-grown youngster. We had to put a good face on a poor situation. At least we were on our guard and hoped that politeness, foresight and diplomacy would help us to find a way out of the mess.

We had hardly sat down by the fire when the tent began to fill with visitors from the neighbouring tents, come to see the strangers. We had our hands full trying to keep our baggage together. The people were as pressing and inquisitive as gipsies. When they had heard that we were pilgrims they urgently recommended us to take one of the men, a particularly good guide, with us on our journey to Lhasa. He wanted us to go by a road somewhat to the south of our route and, according to him, much easier to travel. We exchanged glances. The man was short and powerful and carried a long sword in his belt. Not a type to inspire confidence. However, we accepted his offer and agreed on his pay. There was nothing else to do, for if we got on the wrong side of them they might butcher us out of hand.

The visitors from the other tents gradually drifted away and we prepared to go to bed. One of our two hosts insisted on using my rucksack as a pillow and I had the utmost difficulty in keeping it by me. They probably thought that it contained a pistol. If they did, that suited our book and I hoped to increase their suspicion by my behaviour. At last he stopped bothering me. We remained awake and on our guard all through the night. That was not very difficult, though we were very weary, because the woman muttered prayers without ceasing. It occurred to me that she was praying in advance for forgiveness for the crime her husband intended to commit against us the next day. We were glad when day broke. At first everything seemed peaceful. I exchanged a pocket mirror for some yak’s brains, which we cooked for breakfast. Then we began to get ready to go. Our hosts followed our movements with glowering faces and looked like attacking me when I handed our packs out of the tent to Aufschnaiter. However, we shook them off and loaded our yak. We looked out for our guide but to our relief he was nowhere to be seen. The Khampa family advised us urgently to keep to the southern road, as the nomads from that region were making up a pilgrim caravan to Lhasa. We promised to do so and started off in all haste.

We had gone a few hundred yards when I noticed that my dog was not there. He usually came running after us without being called. As we looked round we saw three men coming after us. They soon caught us up and told us that they too were on the way to the tents of the nomad pilgrims and pointed to a distant pillar of smoke. That looked to us very suspicious as we had never seen such smoke-pillars over the nomad tents. When we asked about the dog they said that he had stayed behind in the tent. One of us could go and fetch him. Now we saw their plan. Our lives were at stake. They had kept the dog back in order to have a chance of separating Aufschnaiter and me, as they lacked the courage to attack us both at the same time. And probably they had companions waiting where the smoke was rising. If we went there we would be heavily outnumbered and they could dispose of us with ease. No one would ever know anything about our disappearance. We were now very sorry not to have listened to the well-meant warnings of the nomads.

As though we suspected nothing we went on a short way in the same direction, talking rapidly to one another. The two men were now on either side of us while the boy walked behind. Stealing a glance to right and left we estimated our chances, if it came to a fight. The two men wore double sheepskin cloaks, as the robbers do, to protect them against knife-thrusts, and long swords were stuck in their belts. Their faces had an expression of lamb-like innocence.

Something had to happen. Aufschnaiter thought we ought first to change our direction, so as not to walk blindly into a trap. No sooner said than done. Still speaking, we abruptly turned away.

The Khampas stopped for a moment in surprise; but in a moment rejoined us and barred our way, asking us, in none too friendly tones, where we were going. “To fetch the dog,” we answered curtly. Our manner of speaking seemed to intimidate them. They saw that we were prepared to go to any lengths, so they let us go and after staring after us for a while they hurriedly went on their way, probably to inform their accomplices.

When we got near the tents, the woman came to meet us leading the dog on a leash. After a friendly greeting we went on, but this time we followed the road by which we had come to the robber camp. There was now no question of going forward — we had to retrace our steps. Unarmed as we were, to continue would have meant certain death. After a forced march we arrived in the evening at the home of the friendly family with whom we had stayed two nights before. They were not surprised to hear of our experiences and told us that the Khampas’ encampment was called Gyak Bongra, a name which inspired fear throughout the countryside. After this adventure it was a blessing to be able to spend a peaceful night with friendly people.

Next morning we worked out our new travel-plan.

There was nothing for it but to take the hard road which led through uninhabited country. We bought more meat from the nomads, as we should probably be a week before seeing a soul.

To avoid going back to Labrang Trova we took a short cut entailing a laborious and steep ascent but leading, as we hoped, to the route we meant to follow. Halfway up the steep slope we turned to look at the view and saw, to our horror, two men following us in the distance. No doubt they were Khampas. They had probably visited the nomads and been told which direction we had taken. What were we to do? We said nothing, but later confessed to one another that we had silently made up our minds to sell our lives as dearly as possible. We tried at first to speed up our pace, but we could not go faster than our yak, who seemed to us to be moving at a snail’s pace. We kept on looking back, but could not be sure whether our pursuers were coming up on us or not.

We fully realised how heavily handicapped we were by our lack of arms. We had only tent-poles and stones to defend ourselves with against their sharp swords. To have a chance we must depend on our wits. ... So we marched on for an hour which seemed endless, panting with exertion and constantly turning round. Then we saw that the two men had sat down. We hurried on towards the top of the ridge, looking as we went for a place which would, if need be, serve as good fighting ground. The two men got up, seemed to be taking counsel together and then we saw them turn round and go back. We breathed again and drove our yak on so that we might soon be out of sight over the far side of the mountain.

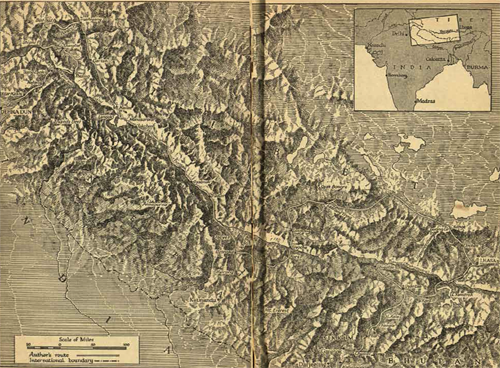

When we reached the crest of the ridge we understood why our two pursuers had preferred to turn back. Before us lay the loneliest landscape I had ever seen. A sea of snowy mountain heights stretched onwards endlessly. In the far distance were the Transhimalayas and like a gap in a row of teeth was the pass which we calculated would lead us to the road we aimed at. First put on the map by Sven Hedin, this pass — the Selala — leads to Shigatse. Being uncertain whether the Khampas had really given up the pursuit, we went on marching even after nightfall. Luckily the moon was high and, with the snow, gave us plenty of light. We could even see the distant ranges.

I shall never forget that night march. I have never been through an experience which placed such a strain on the body and the spirit. Our escape from the Khampas was due to the desolation of the region, the nature of which brought us new obstacles to surmount. It was a good thing that I had long ago thrown away my thermometer. Here it would certainly have marked — 30 degrees as that was the lowest it could record. But that was certainly more than the reality. Sven Hedin registered —40 degrees hereabouts at this season of the year.

We loped on for hours over the virgin snow, and as we went our minds travelled afar on their own journeys. I was tormented by visions of a warm, comfortable room, delicious hot food and steaming hot drinks. Curiously enough it was the evocation of a commonplace buffet at Graz, known to me in my student days, which nearly drove me crazy. Aufschnaiter’s thoughts lay in another direction. He harboured dark plans of revenge against the robbers and swore to come back with a magazine of arms. Woe to all the Khampas!

At last we broke off our march, unloaded our yak and crawled under cover. We had taken out our bag of tsampa and some raw meat as we were ravenously hungry, but as soon as we put a spoonful of dry meal into our mouths the metal stuck to our lips and would not come away. We had to tear it loose, amid curses and oaths. With appetites blunted by this painful experience we huddled up together under our blankets and fell, despite the piercing cold, into the leaden sleep of exhaustion. Next day we toiled on painfully, trudging along in the footprints of our gallant yak and hardly looking up. In the afternoon we suddenly thought we were seeing the fata morgana; for,

far away on the horizon, yet very clearly outlined, appeared three caravans of yaks moving through the snowy scene. They were moving very slowly forward; and then they seemed to come to a stop — but they did not vanish. So it was no mirage. The sight gave us new courage. We summoned up all our strength, drove our yak on, and after three hours’ march reached the spot where the caravans were laagered. There were some fifteen persons in the caravan — men and women — and when we arrived their tents were already pitched. They were astonished to see us, but greeted us kindly and brought us in to get warm by the fire. We found out that they were returning from a combined pilgrimage and trading voyage to Mount Kailas to their homes by Lake Namtso. They had been warned by the district officials about the brigands and so had chosen to follow this difficult route in order to avoid the region infested by the Khampas. They were bringing home fifty yaks and a couple of hundred sheep. The rest of their herds had been bartered for goods and they would have been a rich prize for the robbers. That was why the three groups had joined together and they now invited us to come along with them. Reinforcements could be useful, if they met the Khampas.

What a pleasure it was to be once more sitting by a fire and ladling down hot soup. We felt that this meeting had been ordained by providence. We did not forget our brave Armin, for we knew how much we owed him, and we asked the caravan leader to let us load our baggage on one of their free yaks, for which we would pay a day’s hire. So our beast was able to enjoy a little rest.

Day after day we wandered on with the caravans and pitched our little mountaineer’s tent alongside theirs. We suffered very much from the difficulty of pitching our tent during the hurricanes that often blew in these regions. Unlike the heavy yak-hair tents which could resist the wind, our light canvas hut would not stand up in rough weather and we sometimes had to bivouac in the open air. We swore that if we ever again came on an expedition to Tibet we should have with us three yaks, a driver, a nomad’s tent and a rifle! We thought ourselves very lucky to be allowed to join the caravans. The only thing which disturbed us was the extreme slowness of our progress. Compared with our previous marches we seemed to be gently strolling along. The nomads start early, and after covering three or four miles pitch their tents again and send their animals out to graze. Before nightfall they bring them in and fold them near the tents where they are safe from wolves and can ruminate in peace.

Only now did we perceive how we had imposed on our poor Armin! He must have thought us as mad as the Tibetans did when we spent our days climbing the mountains round Kyirong. During our long periods of rest we devoted much time to filling in our diaries which we had recently neglected. We also began systematically to collect information about the road to Lhasa from the people in the caravan. We questioned them separately and gradually gathered a definite sequence of place-names. That was of great value to us as it would enable us later to ask the nomads the way from one place to another.

We had long agreed that we could not go on spending our life taking short walks. We must leave the caravan in the near future. We took leave of our friends on Christmas Eve and started off again alone. We felt fresh and rested and covered more than fourteen miles on the first day. Late in the evening we came to a wide plain on which were some isolated tents. Their inmates seemed to be very much on their guard, for as we approached a couple of wild-looking men, heavily armed, came up to us. They shouted at us rudely and told us to go to the devil. We did not budge, but put up our hands to show we were not armed and explained to them that we were harmless pilgrims. In spite of our rest days with the caravan, we must have presented a pitiful appearance. After a short colloquy the owner of the larger tent asked us in to spend the night. We warmed ourselves by the fire and were given butter-tea and a rare delicacy — a piece of white bread each. It was stale and hard as stone but this little present on Christmas Eve in the wilds of Tibet meant more to us than a well-cooked Christmas dinner had ever done at home.

Our host treated us roughly at first. When we told him by what route we aimed at reaching Lhasa he said dryly that if we had not been killed up to now, we certainly would be in the next few days. The country was full of Khampas. Without arms we would be an easy prey for them. He said this in a fatalistic tone, as one utters a self-evident truth. We felt very disheartened and asked for his advice. He recommended us to take the road to Shigatse which we could reach in a week. We would not hear of that. He thought for a while and

then advised us to apply to the district officer of this region, whose tent was only a few miles distant. This officer would be able to give us an escort, if we absolutely insisted on going through the robbers’ country.

That evening we had so much to discuss that we hardly gave a thought to Christmas in our own homes. At last we agreed to take a chance and visit the Ponpo. It only took us a few hours to reach his tent and we found it a good omen that he greeted us in a friendly way and placed a tent at our disposal. He then called his colleague and we all four sat down in conference. This time we discarded our story about being Indian pilgrims. We gave ourselves out as Europeans and demanded protection against the bandits. Naturally we were travelling with the permission of the Government and I coolly handed him the old travel-permit, which the Garpon had formerly given us in Gartok. (This document had a story. We three had tossed up to decide who should keep it and Kopp had won. But when he left us, I had had an inspiration and bought it from him. And now its hour had come.) The two officials examined the seal and were clearly impressed by the document. They were now convinced that we had a right to be in Tibet. The only question they asked was where the third member of the party was. We explained that he had been taken sick and had travelled back to India via Tradun. This satisfied the Ponpos who promised us an escort; they would be relieved at different stages by fresh men, who would conduct us as far as the northern main road.

That was a real Christmas greeting for us! And now at last we felt like keeping the Feast. We had stored up a little rice at Kyirong especially for the occasion. This we prepared and invited the two Ponpos to come and share it. They came bringing all sorts of good things with them and we passed a happy, friendly evening together. On the following day a nomad accompanied us to the next encampment and “delivered” us there. It was something like a relay race with us as the baton. Our guide went back after handing us over. With our next guide we made wonderful progress and we realised how useful it was to have a companion who really knew the way, even though he did not provide absolute security against robbers.

Our permanent companions were the wind and the cold.

To us it seemed as if the whole world was a blizzard with a temperature of minus thirty. We suffered much from being insufficiently clothed and I was lucky to be able to obtain an old sheepskin cloak from a tent-dweller. It was tight for me and lacked half a sleeve, but it only cost me two rupees. Our shoes were in a wretched state and could not last much longer: and as for gloves, we hadn’t any. Aufschnaiter had had frostbite in the hands and I had trouble with my feet. We endured our sufferings with dull resignation and it needed a lot of energy to accomplish our daily quota of miles. How happy we would have been to rest for a few days in a warm nomad’s tent. Even the life of the nomads, hard and poverty-stricken as it was, often seemed to us seductively luxurious. But we dared not delay, if we wanted to get through to Lhasa before our provisions ran out. And then? Well, we preferred not to speculate.

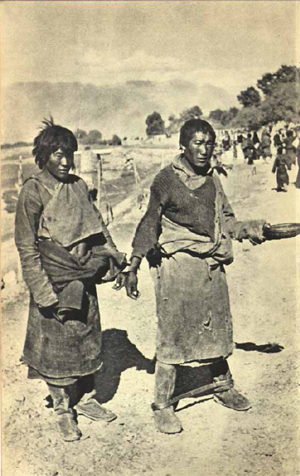

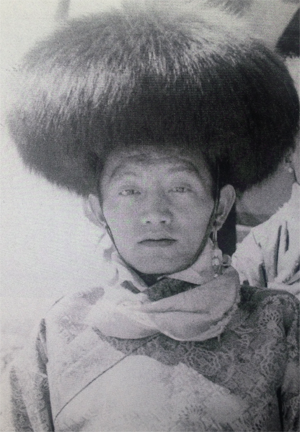

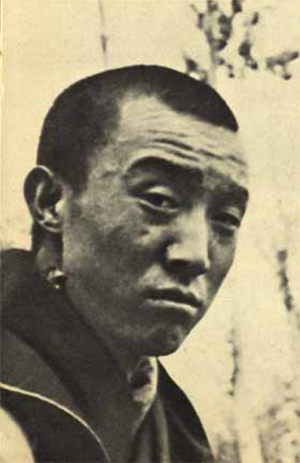

A dog in a Khampa camp in the hills around Yatung. On Tibetan New Year's Day Hopkinson found himself left alone and was able to take a walk and to climb a nearby mountainside. He was surprised to come across a vicious dog, which was owned by a group of Khampa people, whom he was then able to photograph. -- A. J. Hopkinson's Tour of Duty as British Trade Agent, Gyantse, 1927-28

A dog in a Khampa camp in the hills around Yatung. On Tibetan New Year's Day Hopkinson found himself left alone and was able to take a walk and to climb a nearby mountainside. He was surprised to come across a vicious dog, which was owned by a group of Khampa people, whom he was then able to photograph. -- A. J. Hopkinson's Tour of Duty as British Trade Agent, Gyantse, 1927-28

We often saw, happily in the far distance, men on horseback, whom we knew to be Khampas from the unusual type of dogs which accompanied them. These creatures are less hairy than ordinary Tibetan dogs, lean, swift as the wind and indescribably ugly. We thanked God we had no occasion to meet them and their masters at close quarters. On this stage of our travels we discovered a frozen lake which, on later search, we could find on no map. Aufschnaiter sketched it into our map at once. The local inhabitants call it Yochabtso, which means

“water of sacrifice.” It lies at the foot of a chain of glaciers. Before we came to the main road we met some armed footpads carrying modern European rifles against which no courage could have helped us. They, however, let us alone — no doubt because we looked so wretched and down-at-heel. There are times when visible poverty has its advantages.

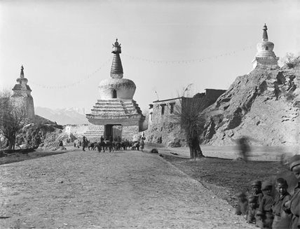

After five days’ march we reached the famous Tasam road. We had always imagined this to be a regular highway which, once reached, would put an end to all the miseries of our march. Imagine our disappointment when we could not find even the trace of a track! The country was in no way different from that through which we had been wandering for weeks. There were, it is true, a few empty tents at which caravans could halt, but no other signs of an organised route.

For the last stage we had been accompanied by a couple of sturdy women, who now handed us over to the Tasam road after a touching farewell. We quartered ourselves in one of the empty tents and lit a fire, after which we took stock of our position. We really had some ground for satisfaction. The most difficult part of our journey lay behind us and

we were now on a frequented route, which led straight to Lhasa, fifteen days’ march ahead. We ought to have been happy in the knowledge that we were so near our goal. But, as a matter of fact, our terrific exertions had got us down to such an extent that we were no longer capable of enjoyment. What with frostbite and lack of money and food, we felt nothing but anxiety. We worried most of all about our animals. My faithful dog was reduced to skin and bones. We had hardly enough food to keep ourselves alive and could spare very little for him. His feet were in such a dreadful state that he could not keep up with us and often we had to wait for hours in our camp before he arrived. The plight of the yak was little better. He had not had enough grass to eat for weeks and was fearfully emaciated. It is true that we had left the snow behind us after leaving Lake Yochabtso, but the grass was scanty and dry and there was little time for grazing.

All the same we had to go forward next day; and the fact that we were now on a caravan route, and had no longer to think of ourselves as

Marco Polos in the unknown gave a spur to our morale.

Our first day on the Tasam route differed very little from our worst stage in uninhabited country. We did not meet a soul. A raging storm, driving snow and swathes of mist made our journey a hell. Fortunately the wind was at our backs and drove us onward. If it had been in our faces, we could not have moved a step forward. All four of us were glad when we saw the roadside tents in the evening. I made the following note in my diary that night:

December 31, 1945. Heavy snowstorm with mist — first mist we have met in Tibet. Temp.: about — 30°. The most exhausting day of our journey up to date. The yak’s load kept slipping off and we nearly got frozen hands adjusting it. Lost the way once and had to go back two miles. Towards evening reached the route-station of Nyatsang. Eight tents. One tent occupied by road officer and his family. Well received.

So this was our second New Year’s Eve in Tibet. Thinking what we had achieved in all this time made one despondent. We were still “illegal” travellers — two down-at-heel, half-starved vagabonds forced to dodge the officials, still bound for a visionary goal which we seemed unable to reach — the Forbidden City. On such a night one’s thoughts turn in sentimental retrospect to home and family. But such dreams could not distract us from the stern reality of the struggle to keep alive which needed all our physical and spiritual strength. For us

an evening in a warm tent was more important than if, in the safety of our homes, we had been given a racing-car as a New Year’s gift. So we kept St. Sylvester’s day in our own fashion. We wanted to stay here somewhat longer in order to thaw ourselves out and to give our beasts a day of rest. Our old travel-paper did its job here too, and the road official was friendly and put his servants at our disposal, sending us water and fuel.

We took it easy and slept late. As we were breakfasting somewhat before noon, there was a stir before the tents. The cook of a Ponpo, wearing a fox-skin hat, had arrived to announce the coming of his master and make preparations for him. He ran around and threw his weight about properly.

The arrival of a high official might be of importance for us, but we had been long enough in Asia to know that “high” official status is a relative conception. For the moment we did not excite ourselves. But things turned out well.

The Ponpo soon arrived on horseback surrounded by a swarm of servants. He was a merchant in the service of the Government and was at present engaged in bringing several hundred loads of sugar and cotton to Lhasa. Hearing about us, he naturally wanted to ask questions. Putting on a virtuous expression I handed him our travel paper, which had the usual good effect. No longer acting the stern official, he invited us to travel with his convoy. That sounded well, so we gave up our rest day and began to pack our baggage as the caravan was to move on in the afternoon. One of the drivers shook his head as he looked at Armin, a veritable skeleton, and finally offered for a small sum to load our baggage on one of the Tasam yaks and let our beast run loose with us. We gladly agreed. Then off we started in haste. We had to go on with the caravan on foot, while the Ponpo and his servants, who had changed horses at the stage, started later. They caught us up before long.

It had been a sacrifice to give up our rest day and set out on a twelve-mile march.

My poor dog was too exhausted to accompany us so I left him behind in the settlement, which was better for him than dying on the road. Marching with the caravan we covered long distances every day. We profited by the patronage of the Ponpo and were everywhere well received. It was only at Lholam that the road official looked askance at us. He would not even give us fuel and insisted on our showing our permit to go to Lhasa. Unfortunately we could not oblige him. However, we had a roof over our heads and were to be glad of it, because soon after our arrival all sorts of

suspicious-looking characters began to gather round the tents. We recognised them at once for Khampas; but we were too tired to bother about them and left the rest of our party to deal with the situation. We at least had nothing worth stealing. Some of them tried to get into our tent, but we shouted at them and they went away.

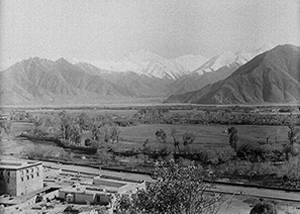

Next morning we missed our yak. We had tethered him the night before and thought he might be grazing somewhere, but Aufschnaiter and I could find no sign of him. The ruffians who had been there the night before had also vanished and the connection was obvious. The loss of our yak was a serious blow to us, and we burst into the tent of the Tasam official and in my rage I threw the pack-saddle and coverings at his feet, telling him that he was responsible for the loss of our beast. We had become very much attached to Armin V, the only yak who had served us well, but we had no time to mourn his loss. We had to catch up the caravan, which had gone ahead some hours before with our baggage.  Nyenchenthanglha range

Nyenchenthanglha range

We had already been marching for some days towards a huge chain of mountains. We knew they were the Nyenchenthanglha range. There was only one way through them and that was the pass which led direct to Lhasa. On our way to the mountains we passed through low hills. The country was completely deserted and we did not even see wild asses. The weather had improved greatly and the visibility was so good that, at a distance of six miles, our next stopping place appeared to be just in front of us.

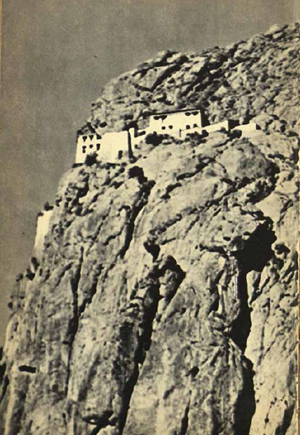

Longchenpa's Hermitage, Gangri Tokar, Tibet

Longchenpa's Hermitage, Gangri Tokar, Tibet

The next halt was at a place called Tokar. From here we began the ascent into the mountains, and the next regular station was five days away. We did not dare to think how we could hold out till then. In any case we did what we could to keep up our strength and bought a lot of meat to keep us going.

Namtso or Lake Nam (officially: Nam Co; Mongolian: Tenger nuur; “Heavenly Lake”; in European literature: Tengri Nor, 30°42′N 90°33′E) is a mountain lake on the border between Damxung County of Lhasa prefecture-level city and Baingoin County of Nagqu Prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, approximately 112 kilometres (70 mi) NNW of Lhasa.

Namtso or Lake Nam (officially: Nam Co; Mongolian: Tenger nuur; “Heavenly Lake”; in European literature: Tengri Nor, 30°42′N 90°33′E) is a mountain lake on the border between Damxung County of Lhasa prefecture-level city and Baingoin County of Nagqu Prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, approximately 112 kilometres (70 mi) NNW of Lhasa.

The days seemed endless and the nights even longer. We travelled through an improbably beautiful landscape and came to one of the largest of the world’s lakes — Nam Tso or Tengri Nor. But we hardly looked at it, though we had for long looked forward to seeing this mighty inland sea. The once-longed-for sight could not shake us out of our apathy.

The climb through the rarefied air had left us breathless, and the prospect of an ascent to nearly 20,000 feet was paralysing. From time to time we looked with wonder at the still higher peaks visible from our route. At last we reached the summit of our pass, Curing La. Before us this pass had only once been crossed by a European. This was Littledale, an Englishman, who came over it in 1895. Sven Hedin had estimated it at nearly 20,000 feet and described it as the highest of the passes in the Transhimalaya region. I think I am right in saying that it is the world’s highest pass traversable all the year round.

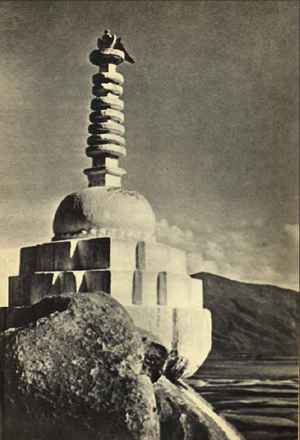

Here we again found the typical cairns, and fluttering over them the brightest-coloured prayer-flags I had yet seen. Near them was a row of stone tables with prayers inscribed on them — an imperishable expression of the joy felt by thousands of pilgrims when, after their long and weary march, they saw the pass opening to them the road to the holiest of cities.

Here, too, we met an astonishing throng of pilgrims returning to their distant homes. How often has this road echoed to the words

“Om mani padme hum,” the time-honoured formula of prayer that all Buddhists use and the pilgrims murmur ceaselessly, hoping, among other things, that it will protect them against what they believe is poison gas and we know to be lack of oxygen. They would do better to keep their mouths closed! From time to time we saw on the slopes below us skeletons of animals, bearing witness to the dangerous nature of the road. Our drivers told us that almost every winter pilgrims lost their lives in snowstorms in this mountain crossing. We thanked God for the good weather which had favoured us during our climb of four thousand feet.

The first part of our descent led over a glacier. I had fresh cause to wonder at the extraordinary sure-footedness of the yaks in finding their way across the ice. As we stumbled along I couldn’t help thinking how much easier it would be to glide over these smooth, uncreviced surfaces on skis. I suppose Aufschnaiter and I were the only people who had ever talked about ski-ing on the pilgrims’ road to Lhasa.

While we were marching along a young couple caught us up. They had come a long distance and, like us, were bound for Lhasa. They were glad to join the caravan and we fell into conversation with them. Their story was a remarkable one.

This pretty young woman with her rosy cheeks and thick black pigtails had lived happy and contented with her three husbands — three brothers they were — for whom she kept house in a nomad tent in the Changthang. One evening a young stranger arrived and asked for lodging. From that moment everything was different. It must have been a case of “Love at first sight.” The young people understood each other without saying anything and next morning went off together. They made nothing of a flight over the wintry plain. Now they were happy to have arrived here, and meant to begin a new life in Lhasa. I remember this young woman as a gleam of sunshine in those hard, heavy days. Once as we were resting she took out her wallet and smilingly handed each of us a dried apricot. This modest gift was as precious to us as the wheat-bread the nomad had given us on Christmas night.

In the course of our journey I realised how strong and enduring Tibetan women are. This very young woman kept up with us easily and carried her pack as well as a man. She had not to worry about her future. In Lhasa she would hire herself out as a daily servant and with her robust country-girl’s health easily earn her living.

We marched for three successive days without coming to tents.

Then we saw in the distance a great column of smoke rising into the sky. We wondered if it came from a chimney or a burning house, but when we got near we saw it was the steam rising from hot springs. We were soon gazing at a scene of great natural beauty. A number of springs bubbled out of the ground, and in the middle of the cloud of steam shot up a splendid little geyser fifteen feet high. After poetry, prose! Our next thought was to have a bath. Our young couple disapproved, but we did not let that deter us. The water was boiling when it came out of the ground, but it was quickly cooled to a bearable temperature by the frosty air. We hurriedly turned one of the pools into a comfortable bath-tub. What a joy it was! Since we had left the hot springs at Kyirong we had not been able to wash or bathe. But, sitting now in water that was almost boiling, the temperature of the air was so low that our wet hair and beards became frozen stiff in an instant. In the brook which flowed out of the hot springs there were a lot of good-sized fish. We hungrily debated how to catch them — we could have boiled them easily enough in the spring — but we found no way, and so, much refreshed, we hurried on to catch up with the caravan.

We spent the night with the yak-drivers in their tent. There I had for the first time in my life a bad attack of sciatica. I had always regarded this painful complaint as a disorder of old age and had never dreamed I should make acquaintance with it so soon. I probably contracted it as a result of sleeping every night on the cold ground.

One morning I could not get up. Besides suffering frightful pain I was chilled by the thought that I would not be able to go on. I clenched my teeth and hoisted myself to my feet and took a few steps. The movement helped, but from that time on I suffered much every day during the first few miles of our march.

In the evening of the fourth day after crossing the pass we reached Samsar, where there was a road station. At last we were in an inhabited place with built houses, monasteries and a castle. This is one of the most important road junctions in Tibet. Five routes meet here and there is a lively caravan traffic. The roadhouses are crowded, and animals are changed in the relay stables. Our Ponpo had already been here for two days, but though on a government mission he had to wait five days for fresh yaks. He procured us a room, fuel and a servant. For the moment the traffic was, so to speak, intense and we had to make up our minds for a long wait, for we could not go on alone.

We used our leisure to go on a day’s excursion to some hot springs which we had seen steaming in the distance. These turned out to be a unique natural phenomenon. We came to a regular lake whose black bubbling waters flowed off into a clear burn. Of course we decided to bathe, and walked into the water at a point where it was pleasantly warm. As we walked up-stream towards the lake it grew hotter and hotter. Aufschnaiter gave up first, but I kept on, hoping that the heat would be good for my sciatica. I wallowed in the hot water. I had brought with me my last piece of soap from Kyirong, and put it on the bank beside me, looking forward to a thorough soaping as the climax of my bath. Unluckily I had not noticed that a crow was observing me with interest. He suddenly swooped and carried off my treasure. I sprang on to the bank with an oath, but in a moment was back in the hot water, my teeth chattering with cold. In Tibet the crows are as thievish as magpies are with us.

On our way back we saw for the first time a Tibetan regiment — five hundred soldiers on manoeuvres. The population is not very enthusiastic about these military exercises, as the soldiers have the right to requisition what they want. They camp in their own tents, which are pitched in very orderly fashion, and there is therefore no billeting; but the local people have to supply them with transport and even riding-horses.

When we came back to our lodging a surprise was awaiting us. They had given us as room-mate a man wearing fetters on his ankles and only able to take very short steps. He told us smilingly, and as if it was a perfectly normal thing, that he was a murderer and a robber and had been condemned first to receive two hundred lashes and afterwards to wear fetters for the rest of his life. This made my flesh creep. Were we already classed with murderers? However, we soon learned that in Tibet a convicted criminal is not necessarily looked down on. Our man had no social disadvantages: he joined in conversation with everybody and lived on alms. And he didn’t do so badly. It had got round that we were Europeans, and curious persons were always coming to see us. Among them was a nice young monk, who was bringing some goods to the monastery of Drebung and had to be off the next day. When he heard that we only had one load of baggage and were very keen to continue our journey, he offered us a free yak in his caravan. He asked no questions about our travel permit. As we had previously reckoned, the nearer we came to the capital, the less trouble we had — the argument being that foreigners who had already travelled so far into Tibet must obviously possess a permit. Nevertheless we thought it wise not to stay too long in any one place, so as not to invite curiosity.

We accepted the monk’s offer at once and bade farewell to our Ponpo with many expressions of gratitude. We started in pitch darkness, not long after midnight. After crossing the district of Yangpachen we entered a valley which debouched into the plain of Lhasa.

So near to Lhasa! The name had always given us a thrill. On our painful marches and during icy nights, we had clung to it and drawn new strength from it. No pilgrim from the most distant province could ever have yearned for the Holy City more than we did.

We had already got much nearer to Lhasa than Sven Hedin. He had made two attempts to get through from the region through which we had come, but had always been held up in Changthang by the escarpment of Nyenchenthanglha. We two poor wanderers were naturally less conspicuous than his caravan and we had our knowledge of Tibetan to help us, in addition to the stratagems we had been compelled to use; so we had some things in our favour.

In the early morning we arrived at the next locality, Dechen, where we were to spend the day. We did not like the idea. There were two district officers in residence and we did not expect them to be taken in by any travel document.

Our friend the monk had not yet arrived. He had been able to allow himself a proper night’s sleep, as he travelled on horseback, and no doubt he started about the time when we arrived at Dechen.

We cautiously started looking for a lodging and had a wonderful “break.”

We made the acquaintance of a young lieutenant who very obligingly offered us his room as he had to leave about midday. He had been collecting in the neighbourhood the money contributions payable in lieu of military service. We ventured to ask him whether he could not take our baggage in his convoy. Of course we would pay for it. He agreed at once and a few hours later we were marching with light hearts out of the village behind the caravan.

Our satisfaction was premature. As we passed the last houses someone called to us and when we turned round we found ourselves facing a distinguished-looking gentleman in rich silk garments. Unmistakably the Ponpo. He asked politely but in an authoritative tone where we had come from and where we were going. Only presence of mind could save us. Bowing and scraping we said we were going on a short walk and had left our papers behind. On our return we would give ourselves the pleasure of waiting on his lordship. The trick succeeded, and we cleared off. We found ourselves marching into spring scenery. The pasture lands grew greener as we went on. Birds twittered in the plantations and we felt too warm in our sheepskin cloaks, though it was only mid-January.

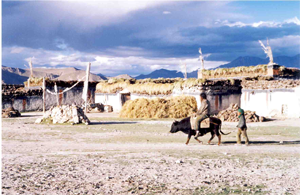

Lhasa was only three days away. All day Aufschnaiter and I tramped on alone and only caught up with the lieutenant and his little caravan in the evening. In this region all sorts of animals were used for transport — donkeys, horses, cows and bullocks. One saw only yaks in the caravans, as the peasants had not enough pasture to feed herds of them. Everywhere we saw the villagers irrigating their fields. The spring gales would come later, and if the soil were too dry it would all be blown away in dust. It often took generations before constant watering made the soil fertile. Here there is very little snow to protect the winter seed and the peasants cannot grow more than one crop. The altitude has naturally a great influence on agriculture. At 16,000 feet only barley will thrive and the peasants are half-nomads. In some regions the barley ripens in sixty days. The Tblung valley through which we were now passing is 12,300 feet above sea-level, and here they also grow roots, potatoes and mustard.

We spent the last night before coming to Lhasa in a peasant’s house. It was nothing like so attractive as the stylish wooden houses in Kyirong. In these parts wood is rare. With the exception of small tables and wooden bedsteads there is practically no furniture. The houses, built of mud bricks, have no windows; light comes in only through the door or the smoke-hole in the ceiling.

Our hosts belonged to a well-to-do peasant family. As is usual in a feudally organised country the peasant manages the property for his landlord, and must produce so much for him before making any profit for himself. In our household there were three sons, two of whom worked on the property whilst the third was preparing to become a monk. The family kept cows, horses, a few fowls and pigs — the first I had seen in Tibet. These are not fed but live on offal and whatever they can grout up in the fields.

We passed a restless night thinking of the next day, which would decide our future. Now came the great question: even if we managed to smuggle ourselves into the town, would we be able to stay there? We had no money left. How, then, were we going to live?

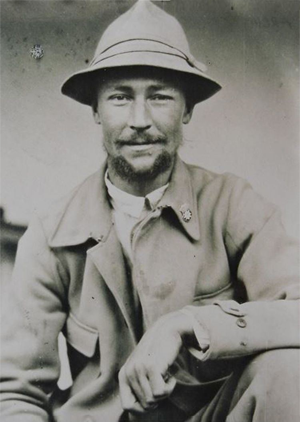

And our appearance! We looked more like brigands from the Changthang than Europeans. Over our stained woollen trousers and torn shirts we wore greasy sheepskin cloaks, which showed, even at a distance, how we had knocked about in them. Aufschnaiter wore the remains of a pair of Indian Army boots on his feet, and my shoes were in fragments. Both of us were more barefoot than shod. No, our appearance was certainly not in our favour. Our beards were perhaps our most striking feature. Like all Mongols, the Tibetans have almost no hair on their faces or bodies; whereas we had long, tangled, luxuriant beards. For this reason we were often taken for Kazaks, a Central Asian tribe whose members migrated in swarms during the war from Soviet Russia to Tibet. They marched in with their families and flocks and plundered right and left, and the Tibetan army was at pains to drive them on into India. The Kazaks are often fair-skinned and blue-eyed and their beards grow normally. It is not surprising that we were mistaken for them, and met with a cold reception from so many nomads. There was nothing to be done about our appearance. We could not spruce ourselves up before going into Lhasa. Even if we had had money, where could we buy clothes?

Since leaving Nangtse — the name of the last village — we had been left to our own devices. The lieutenant had ridden on into Lhasa and we had to bargain with our host about transport for our baggage. He lent us a cow and a servant and when we had paid we had a rupee and a half left and a gold piece sewn up in a piece of cloth. We had decided that if we could not find any transport, we would just leave our stuff behind. Barring our diaries, notes and maps we had nothing of value. Nothing was going to hold us back.