with the original Japanese illustrations

by Shramana Ekai Kawaguchi, Late Rector of Gohyakurakan Monastery, Japan.

Published by The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras.

Theosophical Publishing Society, Benares and London

Printed by Annie Besant at the Vasanta Press, Adyar, Madras, S. India

1909.

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Table of Contents:

• Preface

• I. Novel farewell Presents.

• II. A Year in Darjeeling.

• III. A foretaste of Tibetan barbarism.

• IV. Laying a false scent.

• V. Journey to Nepāl.

• VI. I befriend Beggars.

• VII. The Sublime Himālaya.

• VIII. Dangers ahead.

• IX. Beautiful Tsarang and Dirty Tsarangese.

• X. Fame and Temptation.

• XI. Tibet at Last.

• XII. The World of Snow.

• XIII. A kind old Dame.

• XIV. A holy Cave-Dweller.

• XV. In helpless Plight.

• XVI. A Foretaste of distressing Experiences.

• XVII. A Beautiful Rescuer.

• XVIII. The Lighter Side of the Experiences.

• XIX. The largest River of Tibet.

• XX. Dangers begin in Earnest.

• XXI. Overtaken by a Sand-Storm.

• XXII. 22,650 Feet above Sea-level.

• XXIII. I survive a Sleep in the Snow.

• XXIV. ‘Bon’ and ‘Kyang’.

• XXV. The Power of Buḍḍhism.

• XXVI. Sacred Mānasarovara and its Legends.

• XXVII. Bartering in Tibet.

• XXVIII. A Himālayan Romance.

• XXIX. On the Road to Nature’s Grand Maṇdala.

• XXX. Wonders of Nature’s Maṇdala.

• [x]XXXI. An Ominous Outlook.

• XXXII. A Cheerless Prospect.

• XXXIII. At Death’s Door.

• XXXIV. The Saint of the White Cave revisited.

• XXXV. Some easier Days.

• XXXVI. War Against Suspicion.

• XXXVII. Across the Steppes.

• XXXVIII. Holy Texts in a Slaughter-house.

• XXXIX. The Third Metropolis of Tibet.

• XL. The Sakya Monastery.

• XLI. Shigatze.

• XLII. A Supposed Miracle.

• XLIII. Manners and Customs.

• XLIV. On to Lhasa.

• XLV. Arrival in Lhasa.

• XLVI. The Warrior-Priests of Sera.

• XLVII. Tibet and North China.

• XLVIII. Admission into Sera College.

• XLIX. Meeting with the Incarnate Boḍhisaṭṭva.

• L. Life in the Sera Monastery.

• LI. My Tibetan Friends and Benefactors.

• LII. Japan in Lhasa.

• LIII. Scholastic Aspirants.

• LIV. Tibetan Weddings and Wedded Life.

• LV. Wedding Ceremonies.

• LVI. Tibetan Punishments.

• LVII. A grim Funeral and grimmer Medicine.

• LVIII. Foreign Explorers and the Policy of Seclusion.

• LIX. A Metropolis of Filth.

• LX. Lamaism.

• LXI. The Tibetan Hierarchy.

• LXII. The Government.

• LXIII. Education and Castes.

• LXIV. Tibetan Trade and Industry.

• LXV. Currency and Printing-blocks.

• LXVI. The Festival of Lights.

• LXVII. Tibetan Women.

• LXVIII. Tibetan Boys and Girls.

• LXIX. The Care of the Sick.

• LXX. Outdoor Amusements.

• LXXI. Russia’s Tibetan Policy.

• LXXII. Tibet and British India.

• LXXIII. China, Nepāl and Tibet.

• LXXIV. The Future of Tibetan Diplomacy.

• LXXV. The “Monlam” Festival.

• LXXVI. The Tibetan Soldiery.

• LXXVII. Tibetan Finance.

• LXXVIII. Future of the Tibetan Religions.

• LXXIX. The Beginning of the Disclosure of the Secret.

• LXXX. The Secret Leaks Out.

• LXXXI. My Benefactor’s Noble Offer.

• LXXXII. Preparations for Departure.

• LXXXIII. A Tearful Departure from Lhasa.

• LXXXIV. Five Gates to Pass.

• LXXXV. The First Challenge Gate.

• LXXXVI. The Second and Third Challenge Gates.

• LXXXVII. The Fourth and Fifth Challenge Gates.

• LXXXVIII. The Final Gate passed.

• LXXXIX. Good-bye, Tibet!

• XC. The Labche Tribe.

• XCI. Visit to my Old Teacher.

• XCII. My Tibetan Friends in Trouble.

• XCIII. Among Friends.

• XCIV. The Two Kings of Nepāl.

• XCV. Audience of the Two Kings.

• XCVI. Second Audience.

• XCVII. Once more in Kātmāndu.

• XCVIII. Interview with the Acting Prime Minister.

• XCIX. Painful News from Lhasa.

• C. The King betrays his suspicion.

• CI. Third Audience.

• CII. Farewell to Nepāl and its Good Kings.

• CIII. All’s well that ends well.

Illustrations in the Text.

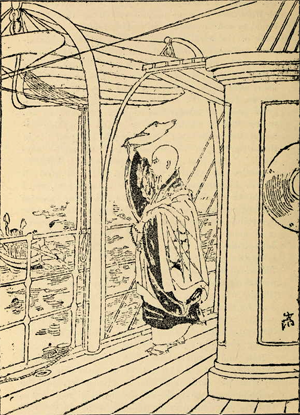

• 1. Author’s departure from Japan.

• 2. The Lama’s execution.

• 3. On the banks of the Bichagori river.

• 4. A horse in difficulties.

• 5. Tsarangese village girls.

• 6. Entering Tibet from Nepāl.

• 7. To a tent of nomad Tibetans.

• 8. A night in the open and a snow-leopard.

• 9. Attacked by dogs and saved by a lady.

• 10. Nearly dying of thirst.

• 11. A sand-storm.

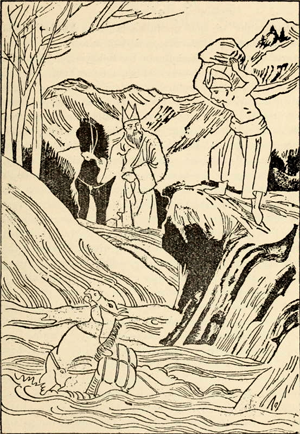

• 12. Struggle in the river.

• 13. Meditating in the face of death.

• 14. A ludicrous race.

• 15. Lake Mānasarovara.

• 16. Religion v. Love.

• 17. Near Mount Kailasa.

• 18. Quarrel between brothers.

• 19. Attacked by robbers.

• 20. The cold moon reflected on the ice.

• 21. Fallen into a muddy swamp.

• 22. Meeting a furious wild yak.

• 23. Outline of the monastery of Tashi Lhunpo.

• 24. Reading the Texts.

• 25. Priest fighting with hail.

• 26. Outline of the residence of the Dalai Lama.

• 27. A vehement philosophical discussion.

• 28. An audience with the Dalai Lama.

• 29. Inner room of the Dalai Lama’s country house.

• 30. Room in the finance secretary’s house.

• 31. Unexpected meeting with friends.

• 32. Girl weeping at being suddenly commanded to marry.

• 33. At the bridegroom’s gate. Throwing an imitation sword at the bride.

• 34. The wife of an Ex-Minister punished in public.

• 35. Funeral ceremonies: cutting up the dead body.

• 36. Lobon Padma Chungne.

• 37. Je Tsong-kha-pa.

• 38. A soothsayer under mediumistic influence falling senseless.

• 39. Flogging as a means of education.

• 40. Priest-traders loading their yaks.

• 41. New year’s reading of the Texts for the Japanese Emperor’s welfare.

• 42. Naming ceremony of a baby.

• 43. A picnic party in summer.

• 44. Prime Minister.

• 45. A corrupt Chief Justice of the monks.

• 46. The final ceremony of the Monlam.

• 47. A scene from the Monlam festival.

• 48. Procession of the Panchen or Tashi Lama in Lhasa.

• 49. Critical meeting with Tsa Rong-ba and his wife.

• 50. Revealing the secret to the Ex-Minister.

• 51. A mysterious Voice in the garden of Sera.

• 52. A distant view of Lhasa.

• 53. Farewell to Lhasa from the top of Genpala.

• 54. Crossing a mountain at midnight.

• 55. Night scene on the Chomo-Lhari and Lham Tso.

• 56. Beautiful scenery in the Tibetan Himālayas.

• 57. The fortress of Nyatong.

• 58. On the way to the snowy Jela-peak.

• 59. Accidental meeting with a friend and compatriot.

• 60. Struggle with a Nepālese soldier.

• 61. Meeting again with an old friend, Lama Buḍḍha Vajra.

• 62. The author and his friend Buḍḍha Vajra enjoying the brilliant snow at Kātmāndu.

• 63. Nāgārjuna’s cave of meditation in Nepāl.

Photogravures.

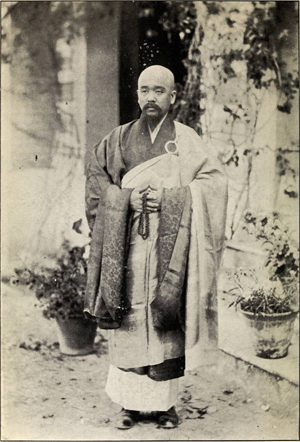

• 1. The Author in 1909. Frontispiece.

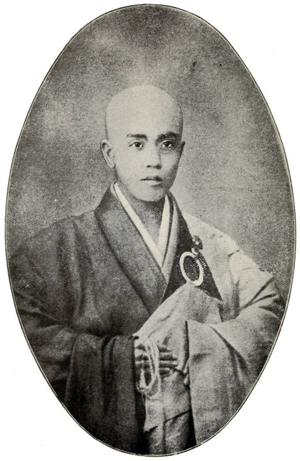

• 2. The Author just before leaving Japan.

• 3. Rai Bahāḍur Saraṭ Chanḍra Ḍās.

• 4. Lama Sengchen Dorjechan.

• 5. The Author meditating under the Boḍhi-tree.

• 6. Passport in Tibetan for the Author’s return to Tibet in the future.

• 7. The Author as a Tibetan Lama at Darjeeling on his return.

• 8. The Author performing ceremonies in Tibetan costume.

• 9. The Prime Minister of Nepāl, H. H. Chanḍra Shamsīr.

• 10. The Commander-in-Chief of Nepāl, H. E. Bhim Shamsīr.

• 11. Mount Gaurīshaṅkara, the highest peak in the world. (At the end of the volume).

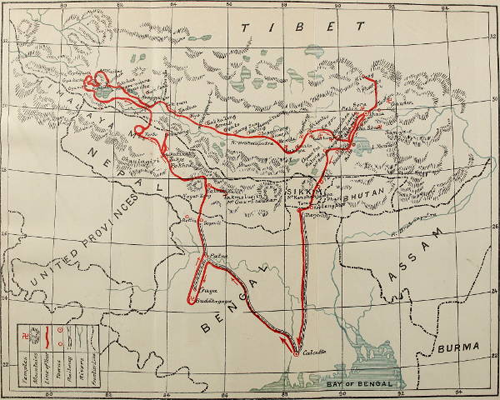

Sketch-map.

1. Chart of the Route followed by the Author. (At the end of the volume.)