by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, Anthropological Institute, etc., Surgeon-Major H.M. Bengal Army

1895

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

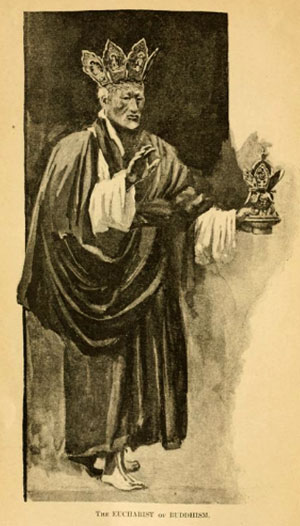

The Eucharist of Buddhism

To William Tennant Gairdner, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S., in admiration of his noble character, philosophic teaching, wide culture, and many labours devoted with exemplary fidelity to the interpretation of nature and the service of man, this book is respectfully dedicated by the Author

Table of Contents:

• Preface

• Note on Pronunciation

• List of Abbreviations

• I. Introductory -- Division of Subject

• A. Historical.

• II. Changes in Primitive Buddhism Leading to Lamaism

• III. Rise, Development, and Spread of Lamaism

• IV. The Sects of Lamaism

• B. Doctrinal

• V. Metaphysical Sources of the Doctrine

• VI. The Doctrine and its Morality

• VII. Scriptures and Literature

• C. Monastic.

• VIII. The Order of Lamas

• IX. Daily Life and routine

• X. Hierarchy and Re-Incarnate Lamas

• D. Buildings

• XI. Monasteries

• XII. Temples and Cathedrals

• XIII. Shrines and Relics (And Pilgrims)

• E. Mythology and Gods

• XIV. Pantheon and Images

• XV. Sacred Symbols and Charms

• F. Ritual and Sorcery

• XVI. Worship and Ritual

• XVII. Astrology and Divination

• XVIII. Sorcery and Necromancy

• G. Festivals and Plays

• XIX. Festivals and Holidays

• XX. Sacred Dramas, Mystic Plays and Masquerades

• H. Popular Lamaism

• XXI. Domestic and Popular Lamaism

• Appendices

• I. Chronological Table

• II. Bibliography

• Index

CHANGES IN PRIMITIVE BUDDHISM LEADING TO LAMAISM.

To understand the origin of Lamaism and its place in the Buddhist system, we must recall the leading features of primitive Buddhism, and glance at its growth, to see the points at which the strange creeds and cults crept in, and the gradual crystallization of these into a religion differing widely from the parent system, and opposed in so many ways to the teaching of Buddha.

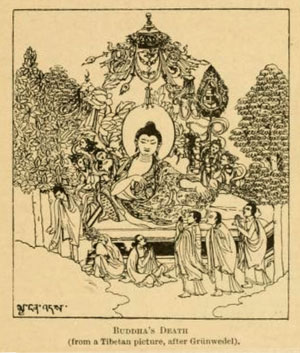

No one now doubts the historic character of Siddharta Gautama, or Sakya Muni, the founder of Buddhism; though it is clear the canonical accounts regarding him are overlaid with legend, the fabulous addition of after days. Divested of its embellishment, the simple narrative of the Buddha's life is strikingly noble and human.

Some time before the epoch of Alexander the Great, between the fourth and fifth centuries before Christ, Prince Siddharta appeared in India as an original thinker and teacher, deeply conscious of the degrading thraldom of caste and the priestly tyranny of the Brahmans, and profoundly impressed with the pathos and struggle of life...

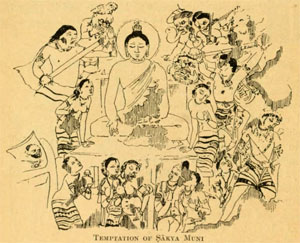

His touching renunciation of his high estate, of his beloved wife, and child, and borne, to become an ascetic, in order to master the secrets of deliverance from sorrow; his unsatisfying search for truth amongst the teachers of his time; his subsequent austerities and severe penance, a much-vaunted means of gaining spiritual insight; his retirement into solitude and self-communion; his last struggle and final triumph — latterly represented as a real material combat, the so-called "Temptation of Buddha"...

[H]is reappearance, confident that he had discovered the secrets of deliverance; his carrying the good tidings of the truth from town to town; his effective protest against the cruel sacrifices of the Brahmans, and his relief of much of the suffering inflicted upon helpless animals and often human beings, in the name of religion...

His system... threw away ritual and sacerdotalism altogether...

About 250 B.C. it was vigorously propagated by the great Emperor Asoka... who, adopting it as his State-religion, zealously spread it throughout his own vast empire, and sent many missionaries into the adjoining lands to diffuse the faith....

In 61 A.D. it spread to China, and through China, to Corea, and, in the sixth century A.D., to Japan... It is believed to have established itself at Alexandria. And it penetrated to Europe, where the early Christians had to pay tribute to the Tartar Buddhist Lords of the Golden Horde; and to the present day it still survives in European Russia among the Kalmaks on the Volga...

Tibet, at the beginning of the seventh century, though now surrounded by Buddhist countries, knew nothing of that religion, and was still buried in barbaric darkness. Not until about the year 640 A.D. did it first receive its Buddhism, and through it some beginnings of civilization among its people....

[In India] Buddha, as the central figure of the system, soon became invested with supernatural and legendary attributes. And as the religion extended its range and influence, and enjoyed princely patronage and ease, it became more metaphysical and ritualistic, so that heresies and discords constantly cropped up, tending to schisms, for the suppression of which it was found necessary to hold great councils.

Of these councils the one held at Jalandhar, in Northern India, towards the end of the first century A.D., under the auspices of the Scythian King Kanishka, of Northern India, was epoch-making, for it established a permanent schism into what European writers have termed the "Northern" and "Southern" Schools...

The point of divergence ... was the theistic Mahayana doctrine, which substituted for the agnostic idealism and simple morality of Buddha, a speculative theistic system with a mysticism of sophistic nihilism in the background....

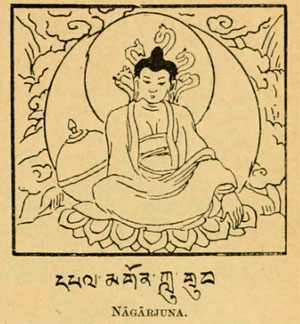

Who the real author of the Mahayana was is not yet known. The doctrine seems to have developed within the Maha-sanghika or "Great Congregation" — a heretical sect which arose among the monks of Vaisali, one hundred years after Buddha's death, and at the council named after that place. Asvaghosha, who appears to have lived about the latter end of the first century A.D., is credited with the authorship of a work entitled On raising Faith in the Mahayana. But its chief expounder and developer was Nagarjuna, who was probably a pupil of Asvaghosha....

Nagarjuna claimed and secured orthodoxy for the Mahayana doctrine by producing an apocalyptic treatise which he attributed to Sakya Muni, entitled the Prajna-paramita, or "the means of arriving at the other side of wisdom," a treatise which he alleged the Buddha had himself composed, and had hid away in the custody of the Naga demigods until men were sufficiently enlightened to comprehend so abstruse a system. And, as his method claims to be a compromise between the extreme views then held on the nature of Nirvana, it was named the Madhyamika, or the system "of the Middle Path."[It seems to have been a common practice for sectaries to call their own system by this title, implying that it only was the true or reasonable belief.]

This Mahayana doctrine was essentially a sophistic nihilism; and under it the goal Nirvana, or rather Pari-Nirvana, while ceasing to be extinction of Life, was considered a mystical state which admitted of no definition. By developing the supernatural side of Buddhism and its objective symbolism, by rendering its salvation more accessible and universal, and by substituting good words for the good deeds of the earlier Buddhists, the Mahayana appealed more powerfully to the multitude and secured ready popularity.

About the end of the first century of our era, then, Kanishka's Council affirmed the superiority of the Mahayana system....

And this new doctrine supported by Kanishka ... became a dominant form of Buddhism throughout the greater part of India; and it was the form which first penetrated, it would seem, to China and Northern Asia.

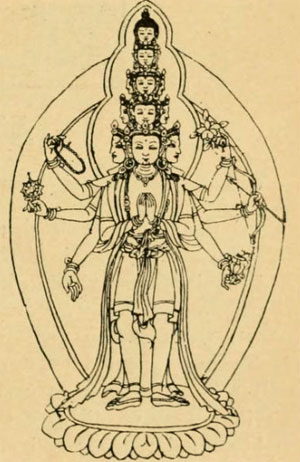

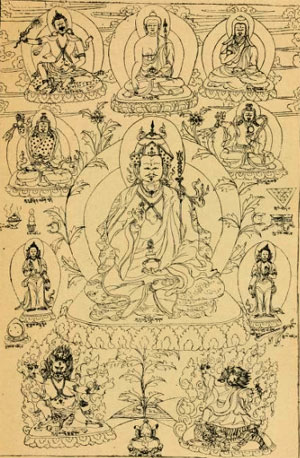

Its idealization of Buddha and his attributes led to the creation of metaphysical Buddhas and celestial Bodhisats, actively willing and able to save, and to the introduction of innumerable demons and deities as objects of worship, with their attendant idolatry and sacerdotalism, both of which departures Buddha had expressly condemned....

As early as about the first century A.D., Buddha is made to be existent from all eternity and without beginning.

And one of the earliest forms given to the greatest of these metaphysical Buddhas — Amitabha, the Buddha of Boundless light — evidently incorporated a Sun-myth, as was indeed to be expected where the chief patrons of this early Mahayana Buddhism, the Scythians and Indo-Persians, were a race of Sun-worshippers....

About 500 A.D. arose the next great development in Indian Buddhism with the importation into it of the pantheistic cult of Yoga, or the ecstatic union of the individual with the Universal Spirit, a cult which had been introduced into Hinduism by Patanjali about 150 B.C....

[D]istinct traces of Yoga are to be found in modern Burmese and Ceylonese Buddhism. And this Yoga parasite, containing within itself the germs of Tantrism, seized strong hold of its host and soon developed its monster outgrowths, which crushed and cankered most of the little life of purely Buddhist stock yet left in the Mahayana.

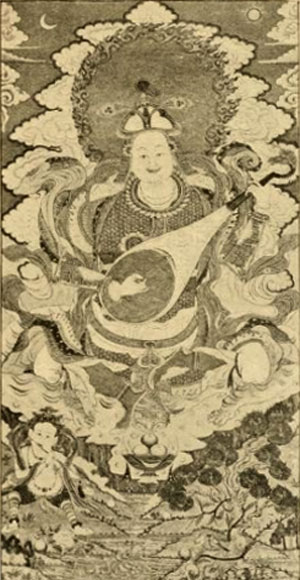

About the end of the sixth century A.D., Tantrism or Sivaic mysticism, with its worship of female energies, spouses of the Hindu god Siva, began to tinge both Buddhism and Hinduism. Consorts were allotted to the several Celestial Bodhisats and most of the other gods and demons, and most of them were given forms wild and terrible, and often monstrous, according to the supposed moods of each divinity at different times. And as these goddesses and fiendesses were bestowers of supernatural power, and were especially malignant, they were especially worshipped...

Such was the distorted form of Buddhism introduced into Tibet about 640 A.D.; and during the three or four succeeding centuries Indian Buddhism became still more debased. Its mysticism became a silly mummery of unmeaning jargon and "magic circles," dignified by the title of Mantrayana or "The Spell-Vehicle"; and this so-called "esoteric," but properly "exoteric," cult was given a respectable antiquity by alleging that its real founder was Nagarjuna, who had received it from the Celestial Buddha Vairocana through the divine Bodhisat Vajrasattva at "the iron tower" in Southern India.

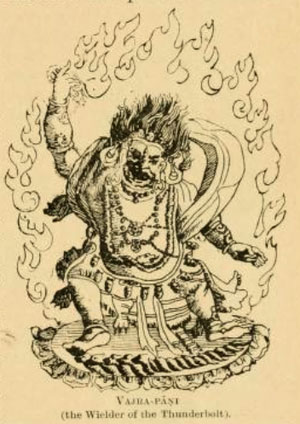

In the tenth century A.D., the Tantrik phase developed in Northern India, Kashmir, and Nepal, into the monstrous and polydemonist doctrine, the Kalacakra, with its demoniacal Buddhas, which incorporated the Mantrayana practices, and called itself the Vajra-yana, or "The Thunderbolt-Vehicle," and its followers were named Vajra-carya, or "Followers of the Thunderbolt."...

In these declining days of Indian Buddhism, when its spiritual and regenerating influences were almost dead, the Muhammadan invasion swept over India, in the latter end of the twelfth century A.D., and effectually stamped Buddhism out of the country...

RISE, DEVELOPMENT, AND SPREAD OF LAMAISM...

Tibetan history, such as there is — and there is none at all before its Buddhist era, nor little worthy of the name till about the eleventh century A.D. — is fairly clear on the point that previous to King Sron Tsan Gampo's marriage in 638-641 A.D., Buddhism was quite unknown in Tibet. And it is also fairly clear on the point that Lamaism did not arise till a century later ...

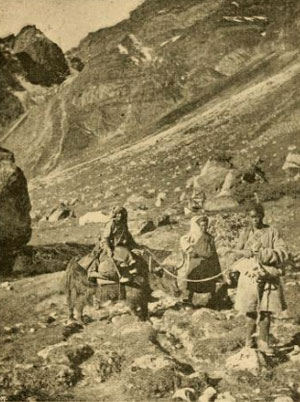

Up till the seventh century Tibet was inaccessible even to the Chinese. The Tibetans of this prehistoric period are seen, from the few glimpses that we have of them in Chinese history about the end of the sixth century, to have been rapacious savages and reputed cannibals, without a written language, and followers of an animistic and devil-dancing or Shamanist religion, the Bon, resembling in many ways the Taoism of China.

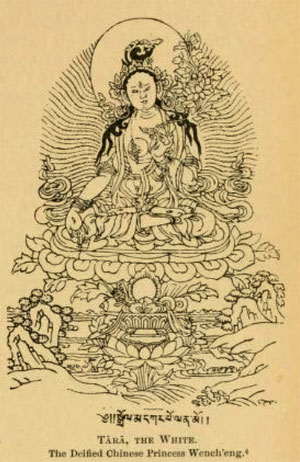

Early in the seventh century, when Muhammad was founding his religion in Arabia, there arose in Tibet a warlike king, who established his authority over the other wild clans of central Tibet, and latterly his son, Sron Tsan Gampo, harassed the western borders of China; so that the Chinese Emperor T'aitsung, of the T'ang Dynasty, was glad to come to terms with this young prince,... and gave him in 641 A.D. the Princess Wench'eng, of the imperial house, in marriage.

Two years previously Sron Tsan Gampo had married Bhrikuti, a daughter of the Nepal King, Amsuvarman; and both of these wives being bigoted Buddhists, they speedily effected the conversion of their young husband, who was then, according to Tibetan annals, only about sixteen years of age, and who, under their advice, sent to India, Nepal, and China for Buddhist books and teachers...

The glimpse got of Sron Tsan in Chinese history shows him actively engaged throughout his life in the very un-Buddhist pursuit of bloody wars with neighbouring states.

The messenger sent by this Tibetan king to India, at the instance of his wives, to bring Buddhist books was called Thon-mi Sam-bhota ... he returned to Tibet, bringing several Buddhist books and the so-called "Tibetan" alphabet, by means of which he now reduced the Tibetan language to writing and composed for this purpose a grammar.

This so-called "Tibetan" character, however, was merely a somewhat fantastic reproduction of the north Indian alphabet current in India at the time of Sam-bhota's visit. It exaggerates the nourishing curves of the "Kutila" which was then coming into vogue in India, and it very slightly modified a few letters to adapt them to the peculiarities of Tibetan phonetics. Thonmi translated into this new character several small Buddhist texts...

[Sron Tsan Gampo] was not the saintly person the grateful Lamas picture, for he is seen from reliable Chinese history to have been engaged all his life in bloody wars, and more at home in the battlefield than the temple. And he certainly did little in the way of Buddhist propaganda, beyond perhaps translating a few tracts into Tibetan, and building a few temples to shrine the images received by him in dower, and others which he constructed. He built no monasteries.

After Sron Tsan Gampo's death, about 650 A.D., Buddhism made little headway against the prevailing Shamanist superstitions, and seems to have been resisted by the people until about a century later in the reign of his powerful descendant Thi-Sron Detsan, who extended his rule over the greater part of Yunnan and Si-Chuen, and even took Changan, the then capital of China....

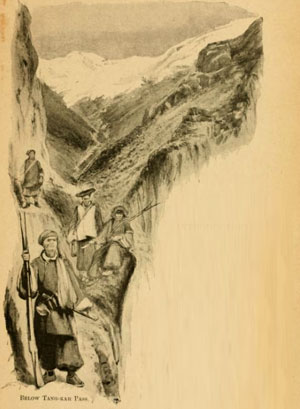

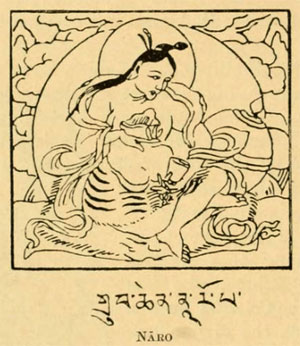

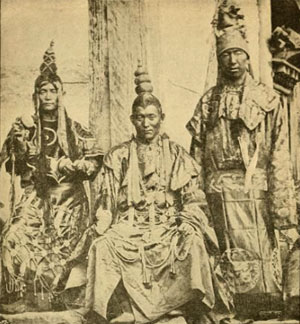

He succeeded to the throne when only thirteen years old, and a few years later he sent to India for a celebrated Buddhist priest to establish an order in Tibet; and he was advised, it is said, by his family priest, the Indian monk Santarakshita, to secure if possible the services of his brother-in-law, Guru Padma-sambhava, a clever member of the then popular Tantrik Yogacarya school, and at that time, it is said, a resident of the great college of Nalanda, the Oxford of Buddhist India.

This Buddhist wizard, Guru Padma-sambhava, promptly responded to the invitation of the Tibetan king, and accompanied the messengers back to Tibet in 747 A.D....

Udyana, his native land, was famed for the proficiency of its priests in sorcery, exorcism, and magic. Hiuen Tsiang, writing a century previously, says regarding Udyana: "The people are in disposition somewhat sly and crafty. They practise the art of using charms. The employment of magical sentences is with them an art and a study."...

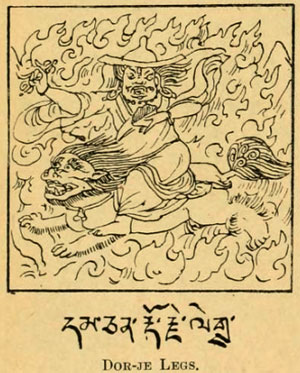

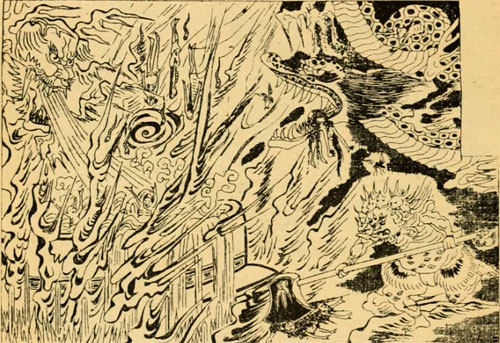

The Tibetans, steeped in superstition which beset them on every side by malignant devils, warmly welcomed the Guru as he brought them deliverance from their terrible tormentors. Arriving in Tibet in 747 A.D., he vanquished all the chief devils of the land, sparing most of them on their consenting to become defenders of his religion, while he on his part guaranteed that in return for such services they would be duly worshipped and fed...

The Guru's most powerful weapons in warring with the demons were the Vajra (Tibetan, dor-je), symbolic of the thunderbolt of Indra (Jupiter), and spells extracted from the Mahayana gospels, by which he shattered his supernatural adversaries....

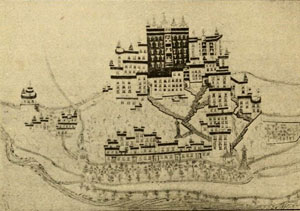

Under the zealous patronage of King Thi-Sron Detsan he built at Sam-yas in 749 A.D. the first Tibetan monastery....

On the building of Sam-yas, said to be modelled after the Indian Odantapura of Magadha, the Guru, assisted by the Indian monk Santa-rakshita, instituted there the order of the Lamas. Santa-rakshita was made the first abbot and laboured there for thirteen years...

La-ma is a Tibetan word meaning the "Superior One," and corresponds to the Sanskrit Uttara. It was restricted to the head of the monastery, and still is strictly applicable only to abbots and the highest monks; though out of courtesy the title is now given to almost all Lamaist monks and priests. The Lamas have no special term for their form of Buddhism. They simply call it "The religion" or "Buddha's religion"; and its professors are "Insiders," or "within the fold" (nan-pa), in contradistinction to the non-Buddhists or "Outsiders" (chi-pa or pyi-'lin), the so-called "pe-ling" or foreigners of English writers. And the European term "Lamaism" finds no counterpart in Tibetan....

The most learned of these young Lamas was Vairocana, who translated many Sanskrit works into Tibetan....

Vairocana is made an incarnation of Buddha's faithful attendant and cousin Ananda; and on account of his having translated many orthodox scriptures, he is credited with the composition or translation and hiding away of many of the fictitious scriptures of the unreformed Lamas, which were afterwards "discovered" as revelations.

It is not easy now to ascertain the exact details of the creed -- the primitive Lamaism— taught by the Guru, for all the extant works attributed to him "were composed several centuries later by followers of his twenty-five Tibetan disciples. But judging from the intimate association of his name with the essentials of Lamaist sorceries, and the special creeds of the old unreformed section of the Lamas— the Nin-ma-pa— who profess and are acknowledged to be his immediate followers, and whose older scriptures date back to within two centuries of the Guru's time, it is evident that his teaching was of that extremely Tantrik and magical type of Mahayana Buddhism which was then prevalent in his native country of Udyan and Kashmir. And to this highly impure form of Buddhism, already covered by so many foreign accretions and saturated with so much demonolatry, was added a portion of the ritual and most of the demons of the indigenous Bon-pa religion, and each of the demons was assigned its proper place in the Lamaist pantheon.

Primitive Lamaism may therefore be defined as a priestly mixture of Sivaite mysticism, magic, and Indo-Tibetan demonolatry, overlaid by a thin varnish of Mahayana Buddhism. And to the present day Lamaism still retains this character...

Its doctrine of Karma, or ethical retribution, appealed to the fatalism which the Tibetans share with most eastern races...

The new religion was actively opposed by the priests of the native religion, called Bon, and these were supported by one of the most powerful ministers. Some of the so-called devils which are traditionally alleged to have been overcome by the Guru were probably such human adversaries. It is also stated that the Bon-pa were now prohibited making human and other bloody sacrifice as was their wont; and hence is said to have arisen the practice of offering images of men and animals made of dough.

Lamaism was also opposed by some Chinese Buddhists, one of whom, entitled the Mahayana Hwa-shang, protested against the kind of Buddhism which Santa-rakshita and Padma-sambhava were teaching. But he is reported to have been defeated in argument and expelled from the country by the Indian monk Kamala-sila...

Padma-sambhava had twenty-five disciples, each of whom is credited with magical power, mostly of a grotesque character. And these disciples he instructed in the way of making magic circles for coercing the demons and for exorcism...

In the latter half of the ninth century under king Ralpachan, the grandson of Thi-Sron Detsan, the work of the translation of scriptures and the commentaries of Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Vasubandhu, etc., was actively prosecuted. Among the Indian translators employed by him were Jina Mitra, Silendrabodhi, Surendrabodhi, Prajna-varman, Dana-sila, and Bodhimitra, assisted by the Tibetans Pal-brtsegs, Ye-s'e-sde, Ch'os-kyi-G-yal-ts'an, and at least half of the two collections as we know them is the work of their hands. And he endowed most of the monasteries with state-lands and the right to collect tithes and taxes. He seems to have been the first Tibetan sovereign who started a regular record of the annals of his country, for which purpose he adopted the Chinese system of chronology.

His devotion to Buddhism appears to have led to his murder about 899, at the instigation of his younger brother Lan Darma, — the so-called Julian of Lamaism — who then ascended the throne, and at once commenced to persecute the Lamas and did his utmost to uproot the religion. He desecrated the temples and several monasteries, burned many of their books, and treated the Lamas with the grossest indignity, forcing many to become butchers.

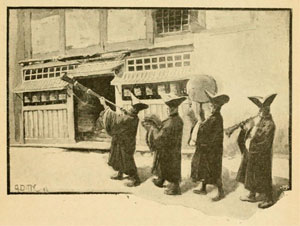

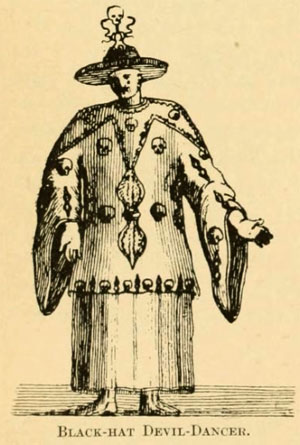

But Lan Darma's persecution was very mild for a religious one, and very short-lived. He was assassinated in the third year of his reign by a Lama of Lha-lun named Pal-dorje, who has since been canonized by his grateful church, and this murderous incident forms a part of the modern Lamaist masquerade. This Lama, to effect his purpose, assumed the guise of a strolling black-hat devil-dancer, and hid in his ample sleeves a bow and arrow. His dancing below the king's palace, which stood near the north end of the present cathedral of Lhasa, attracted the attention of the king, who summoned the dancer to his presence, where the disguised Lama seized an opportunity while near the king to shoot him with the arrow, which proved almost immediately fatal. In the resulting tumult the Lama sped away on a black horse, which was tethered near at hand, and riding on, plunged through the Kyi river on the outskirts of Lhasa, whence his horse emerged in its natural white colour, as it had been merely blackened by soot, and he himself turned outside the white lining of his coat, and by this stratagem escaped his pursuers. The dying words of the king were: "Oh, why was I not killed three years ago to save me committing so much sin, or three years hence, that I might have rooted Buddhism out of the land?"

On the assassination of Lan Darma the Lamas were not long in regaining their lost ground... [F]rom this time forth the Lamaist church steadily grew in size and influence until it reached its present vast dimensions, culminating in the priest-kings at Lhasa.

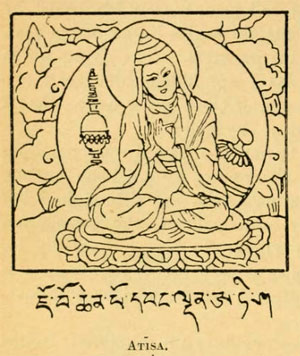

By the beginning of the eleventh century A.D., numerous Indian and Kashmiri monks were again frequenting Tibet. And in 1038 A.D. arrived Atisa, the great reformer of Lamaism...

Atisa was nearly sixty years of age when he visited Tibet. He at once started a movement which may be called the Lamaist Reformation, and he wrote many treatises.

His chief disciple was Domton, the first hierarch of the new reformed sect, the Kadam-pa, which, three-and-a-half centuries later, became the Ge-lug-pa, now the dominant sect of Tibet, and the established church of the country.

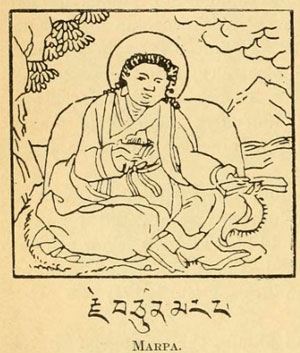

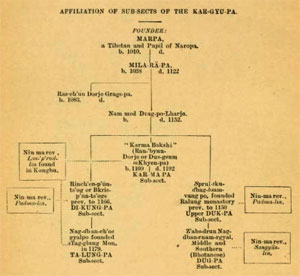

Atisa's reformation resulted not only in the new sect, Kadam-pa, with which he most intimately identified himself, but it also initiated, more or less directly, the semi-reformed sects of Kar-gyu-pa and Sakya-pa, as detailed in the chapter on Sects...

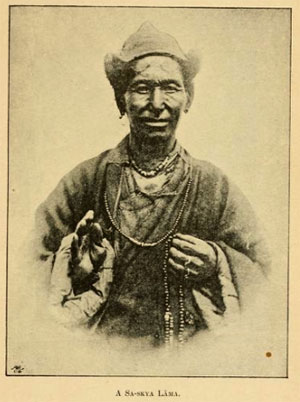

In the second half of the thirteenth century, Lamaism received a mighty accession of strength at the hands of the great Chinese emperor, Khubilai Khan. Tibet had been conquered by his ancestor, Jenghiz Khan, about 1206 A.D., and Khubilai was thus brought into contact with Lamaism...

Just as Charlemagne created the first Christian pope, so the emperor Khubilai recognized the Lama of Saskya, or the Sakya Pandita, as head of the Lamaist church, and conferred upon him temporary power as the tributary ruler of Tibet, in return for which favour he was required to consecrate or crown the Chinese emperors... Khubilai actively promoted Lamaism and built many monasteries in Mongolia, and a large one at Pekin. Chinese history attributes to him the organisation of civil administration in Tibet...

The Sakya pope, assisted by a staff of scholars, achieved the great work of translating the bulky Lamaist canon (Kah-gyur) into Mongolian after its revision and collation with the Chinese texts....

Under the succeeding Mongol emperors, the Sakya primacy seems to have maintained much of its political supremacy, and to have used its power as a church-militant to oppress its rival sects. Thus it burned the great Kar-gyu-pa monastery of Dikung about 1320 A.D. But on the accession of the Ming dynasty in 1368 A.D. the Chinese emperors deemed it politic, while conciliating the Lamas, as a body, by gifts and titles, to strike at the Sakya power by raising the heads of two other monasteries to equal rank with it, and encouraged strife amongst them.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century a Lama named Tson-K'a-pa re-organized Atisa's reformed sect, and altered its title to "The virtuous order," or Ge-lug-pa. This sect soon eclipsed all the others; and in five generations it obtained the priest-kingship of Tibet, which it still retains to this day. Its first Grand Lama was Tson-K'a-pa's nephew, Geden-dub, with his succession based on the idea of re-incarnation, a theory which was afterwards, apparently in the reign of the fifth Grand Lama, developed into the fiction of re-incarnated reflexes of the divine Bodhisat Avalokita, as detailed in the chapter on the Hierarchy.

In 1640, the Ge-lug-pa leapt into temporal power under the fifth Grand Lama, the crafty Nag-wan Lo-zang. At the request of this ambitious man, a Mongol prince, Gusri Khan, conquered Tibet, and made a present of it to this Grand Lama, who in 1650 was confirmed in his sovereignty by the Chinese emperor, and given the Mongol title of Dalai, or "(vast as) the Ocean." And on account of this title he and his successors are called by some Europeans "the Dalai (or Tale) Lama" though this title is almost unknown to Tibetans, who call these Grand Lamas "the great gem of majesty" (Gyal-wa Rin-po-ch'e).

This daring Dalai Lama, high-handed and resourceful, lost no time in consolidating his rule as priest-king and the extension of his sect by the forcible appropriation of many monasteries of the other sects, and by inventing legends magnifying the powers of the Bodhisat Avalokita and posing himself as the incarnation of this divinity, the presiding Bodhisat of each world of re-birth, whom he also identified with the controller of metempsychosis, the dread Judge of the Dead before whose tribunal all mortals must appear.

Posing in this way as God-incarnate, he built himself the huge palace-temple on the hill near Lhasa, which he called Potala, after the mythic Indian residence of his divine prototype Avalokita, "The Lord who looks down from on high," whose symbols he now invested himself with. He also tampered unscrupuously with Tibetan history in order to lend colour to his divine pretensions, and he succeeded perfectly. All the other sects of Lamas acknowledged him and his successors to be of divine descent, the veritable Avalokita-in-the-flesh. And they also adopted the plan of succession by re-incarnate Lamas and by divine reflexes...

The declining years of this great Grand Lama, Nag-wan, were troubled by the cares and obligations of the temporal rule... On account of these political troubles his death was concealed for twelve years by the minister De-Si, who is believed to have been his natural son. And the succeeding Grand Lama, the sixth, proving hopelessly dissolute, he was executed at the instigation of the Chinese government, which then assumed the suzerainty, and which has since continued to control in a general way the temporal affairs, especially its foreign policy, and also to regulate more or less the hierarchal succession...

But the Ge-lug-pa sect, or the established church, going on the lines laid down for it by the fifth Grand Lama, continued to prosper, and his successors, despite the presence of a few Chinese officials, are now, each in turn, the de facto ruler of Tibet...

The population of Tibet itself is probably not more than 4,000,000, but almost all of these may be classed as Lamaists, for although a considerable proportion of the people in eastern Tibet are adherents of the Bon, many of these are said to patronize the Lamas as well, and the Bon religion has become assimilated in great part to un-reformed Lamaism...

In China, except for a few monasteries at Pekin, etc., and these mostly of Mongol monks, the Lamaist section of Chinese Buddhists seems confined to the extreme western frontier, especially the former Tibetan province of Amdo. Probably the Lamaists in China number no more than about 1,000,000...

Mongolia may be considered almost wholly Lamaist...

Manchuria is largely Lamaist...

Ladak, to which Asoka missionaries are believed to have penetrated, is now entirely Lamaist in its form of Buddhism, and this is the popular religion...

The majority of the Nepalese Buddhists are now Lamaist.

Bhotan is wholly Lamaist, both in its religion and temporal government...

Lamaism is the state religion [in Sikkim]...

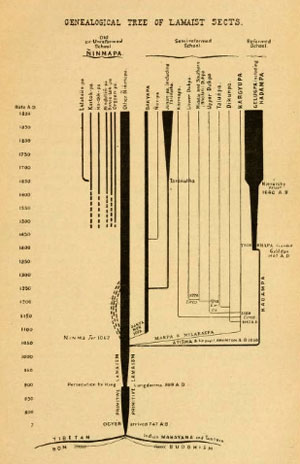

THE SECTS OF LAMAISM...

No sects appear to have existed prior to Lan-Darma's persecution, nor till more than a century and a half later. The sectarial movement seems to date from the Reformation started by the Indian Buddhist monk Atisa, who, as we have seen, visited Tibet in 1038 A.D.

Atisa, while clinging to Yoga and Tantrism, at once began a reformation on the lines of the purer Mahayana system, by enforcing celibacy and high morality, and by deprecating the general practice of the diabolic arts...

The first of the reformed sects and the one with which Atisa most intimately identified himself was called the Kah-dam-pa, or "those bound by the orders (commandments)"; and it ultimately, three and a half centuries later, in Tson K'apa's hands, became less ascetic and more highly ritualistic under the title of "The Virtuous Style," Ge-lug-pa, now the dominant sect in Tibet...

The rise of the Kah-dam-pa (Ge-lug-pa) sect was soon followed by the semi-reformed movements of Kar-gyu-pa and Sakya-pa, which were directly based in great measure on Atisa's teaching. The founders of those two sects had been his pupils, and their new sects may be regarded as semi-reformations adapted for those individuals who found his high standard too irksome, and too free from their familiar demonolatry.

The residue who remained wholly unreformed and weakened by the loss of their best members, were now called the Nin-ma-pa or "the old ones," as they adhered to the old practices. And now, to legitimize many of their unorthodox practices which had crept into use, and to admit of further laxity, the Nin-ma-pa resorted to the fiction of Ter-ma or hidden revelations...

Nin-ma Lamas now began to discover new gospels, in caves and elsewhere, which they alleged were hidden gospels of the Guru, Saint Padma. And these so-called "revealers," but really the composers of these Ter-ma treatises, also alleged as a reason for their ability to discover these hidden gospels, that each of them had been, in a former birth, one or other of the twenty-five disciples of St. Padma.

These "Revelations" treat mainly of Shamanist Bon-pa and other demoniacal rites which are permissible in Lamaist practice; and they prescribed the forms for such worship...

The Ge-lug-pa arose at the beginning of the fifteenth century A.D. as a regeneration of the Kah-dam-pa by Tson-K'a-pa ...

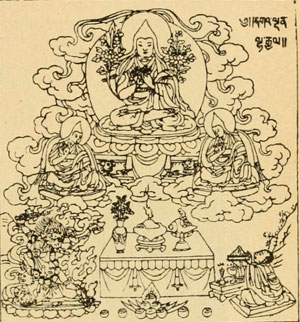

[Tson-K'a-pa] was probably, as Huc notes, influenced by the Roman Catholic priests, who seem to have been settled near the place of his birth... And by the Ge-lug-pa he is considered superior even to St. Padma and Atisa, and is given the chief place in most of their temples...

He collected the scattered members of the Kah-dam-pa from their retreats, and housed them in monasteries, together with his new followers, under rigid discipline, setting them to keep the two hundred and thirty-five Vinaya rules, and hence obtaining for them the title of Vinaya-keepers or "Dul-wa Lamas." He also made them carry a begging-bowl, prayer-carpet, and wear patched robes of a yellow colour, after the fashion of the Indian mendicant monks. And he attracted followers by instituting a highly ritualistic service, in part apparently borrowed from the Christian missionaries, who undoubtedly were settled at that time in Tson-K'a, the province of his early boyhood in Western China...

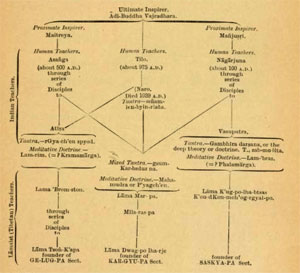

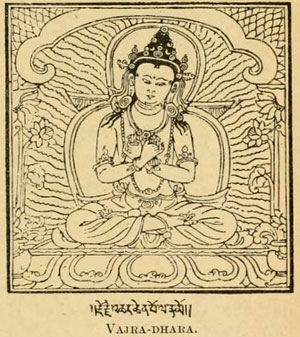

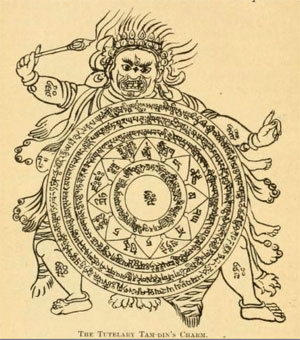

The special sectarian distinctions of the Ge-lug-pa, which represent the earlier Kah-dam-pa sect, are that this sect has the mythical Vajradhara as its Adi-Buddha; and derives its divine inspiration from Maitreya — "the coming Buddha," through the Indian Saints ranging from Asanga down to Atisa, and through the Tibetan Saints from his disciple Brom-ton to Tson-K'a-pa (Je-Rim-po-ch'e). The Ge-lug-pa mystical insight (Ta-wa) is termed the Lam-rim or "the Graded Path," and their Tantra is the "Vast Doer" (rgya-ch'en spyod). Its tutelary demoniacal Buddha is Vajra-bhairava (Dorje-'jig-je), supported by Samvara (Dem-ch'og) and Guhya-kala (Sang-du). And its Guardian demons are "The Six-armed Gon-po or Lord" and the Great horse-necked Hayagriva (Tam-din), or the Red Tiger-Devil.

But, through Atisa, the Ge-lug-pa sect, as is graphically shown in the foregoing table, claims also to have received the essence of Manjusri's doctrine, which is the leading light of the Sakya-pa sect. For Atisa is held to be an incarnation of Manjusri, the Bodhisat of Wisdom....

Tson-K'a-pa's nephew, Ge-dun-dub, was installed in 1439 as the first Grand Lama of the Ge-lug-pa Church, and he built the monastery of Tashi-lhunpo, in 1445, while his fellow workers Je-She-rabSen-age Gyal-Ts'ab-je and Khas-grub-je had built respectively De-p'ung (in 1414), and Se-ra (in 1417), the other great monasteries of this sect.

Under the fourth of these Grand Lamas, the Ge-lug-pa Church was vigorously struggling for supreme power and was patronized by the Mongol minister of the Chinese Government named Chong-Kar, who, coming to Lhasa as an ambassador, usurped most of the power of the then king of Tibet, and forced several of the Kar-gyu and Nin-ma monasteries to join the Ge-lug-pa sect, and to wear the yellow caps...

Since then, however, the Ge-lug-pa sect has gradually retrograded in its tenets and practice, till now, with the exception of its distinctive dress and symbols, celibacy and greater abstinence, and a slightly more restricted devil-worship, it differs little from the other Lamaist sects, which in the pride of political power it so openly despises...

The Z'i-jed-pa...

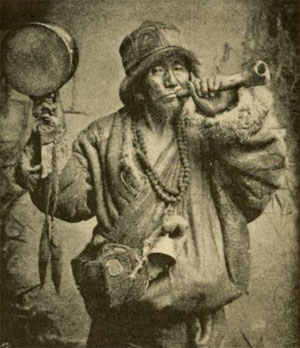

The Z'i-jed-pa ("the mild doer"), or passionless Ascetic, is a homeless mendicant of the Yogi class, and belonging to no sect in particular, though having most affinity with the Kar-gyu-pa. They are now almost extinct, and all are regarded as saints, who in their next birth must certainly attain Nirvana. They carry thigh-bone trumpets, skull-drums, etc., and in the preparation of these instruments from human bones, they are required to eat a morsel of the bone or a shred of the corpse's skin....

Summary of Sects.

It will thus be seen that Lamaist sects seem to have arisen in Tibet, for the first time, in the latter part of the eleventh century A.D., in what may be called the Lamaist Reformation, about three centuries after the foundation of Lamaism itself.

They arose in revolt against the depraved Lamaism then prevalent, which was little else than a priestly mixture of demonolatry and witchcraft. Abandoning the grosser charlatanism, the new sects returned to celibacy and many of the purer Mahayana rules.

In the four centuries succeeding the Reformation, various sub-sects formed, mostly as relapses towards the old familiar demonolatry.

And since the fifteenth century A.D., the several sects and sub-sects, while rigidly preserving their identity and exclusiveness, have drifted down towards a common level where the sectarian distinctions tend to become almost nominal.

But neither in the essentials of Lamaism itself, nor in its sectarian aspects do the truly Buddhist doctrines, as taught by Sakya Muni, play a leading part....

Buddhist Theory of the Universe...

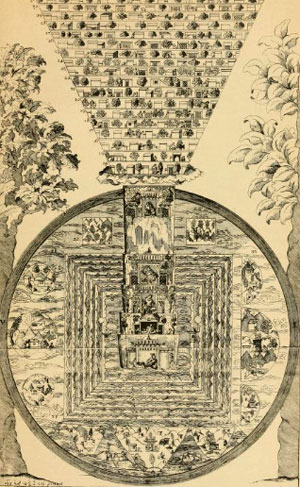

This, our human, world is only one of a series ... which together form a universe or chiliocosm, of which there are many.

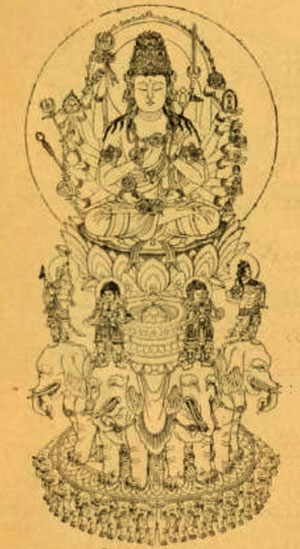

Each universe, set in unfathomable space, rests upon a warp and woof of "blue air"or wind, liked crossed thunderbolts (vajra), hard and imperishable as diamonds (vajra?), upon which is set "the body of the waters," upon which is a foundation of gold, on which is set the earth, from the axis of which towers up the great Olympus— Mt. Meru (Su-meru, Tib., Ri-rab) 84,000 miles high, surmounted by the heavens, and overlying the hills.

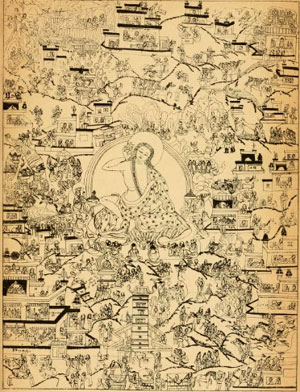

In the ocean around this central mountain, the axis of the universe, are set the four great continental worlds with their satellites, all with bases of solid gold in the form of a tortoise — as this is a familiar instance to the Hindu mind of a solid floating on the waters. And the continents are separated from Mt. Meru by seven concentric rings of golden mountains, the inmost being 40,000 miles high, and named "The Yoke" (Yugandara), alternating with seven oceans, of fragrant milk, curds, butter, blood or sugar-cane juice, poison or wine, fresh water and salt water. These oceans diminish in width and depth from within outwards from 20,000 to 625 miles, and in the outer ocean lie the so-called continental worlds. And the whole system is girdled externally by a double iron-wall (Cakravata) 312-1/2 miles high and 3,602,625 miles in circumference, — for the oriental mythologist is nothing if not precise. This wall shuts out the light of the sun and moon, whose orbit is the summit of the inmost ring of mountains, along which the sun, composed of "glazed fire" enshrined in a crystal palace, is driven in a chariot with ten (seven) horses; and the moon, of "glazed water," in a silver shrine drawn by seven horses, and between these two hang the jewelled umbrella of royalty and the banner of victory, as shown in the figure. And inhabiting the air, on a level with these, are the eight angelic or fairy mothers. Outside the investing wall of the universe all is void and in perpetual darkness until another universe is reached....

In the very centre of this cosmic system stands ''The king of mountains," Mount Meru, towering erect "like the handle of a mill-stone," while half-way up its side is the great wishing tree, the prototype of our "Christmas tree," and the object of contention between the gods and the Titans. Meru has square sides of gold and jewels. Its eastern face is crystal (or silver), the south is sapphire or lapis lazuli (vaidurya) stone, the west is ruby (padmaraga), and the north is gold, and it is clothed with fragrant flowers and shrubs. It has four lower compartments before the heavens are reached. The lowest of these is inhabited by the Yaksha genii — holding wooden plates. Above this is "the region of the wreath-holders" (Skt., Srag-dhara), which seems to be a title of the bird-like, or angelic winged Garudas. Above this dwell the "eternally exalted ones," above whom are the Titans....

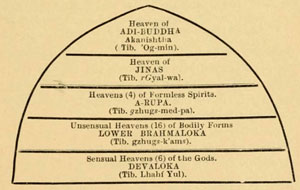

The Heavens and the Gods....

In the centre of this paradise is the great city of Belle-vue (Sudarsana), within which is the celestial palace of Vaijayanta (Amaravati) the residence of Indra (Jupiter), the king of the gods. It is invested by a wall and pierced by four gates, which are guarded by the four divine kings of the quarters. It is a three-storied building; Indra occupying the basement, Brahma the middle, and the indigenous Tibetan war-god — the dGra-lha — as a gross form of Mara, the god of Desire, the uppermost story. This curious perversion of the old Buddhist order of the heavens is typical of the more sordid devil-worship of the Lamas who, as victory was the chief object of the Tibetans, elevated the war-god to the highest rank in their pantheon, as did the Vikings with Odin where Thor, the thunder-god, had reigned supreme. The passionate war-god of the Tibetans is held to be superior even to the divinely meditative state of the Brahma....

To account for the high position thus given to the war-god, it is related that he owes it to the signal assistance rendered by him to the gods in opposing the Asuras...

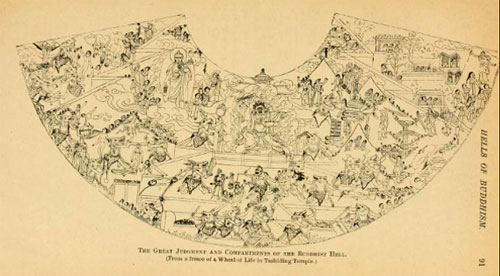

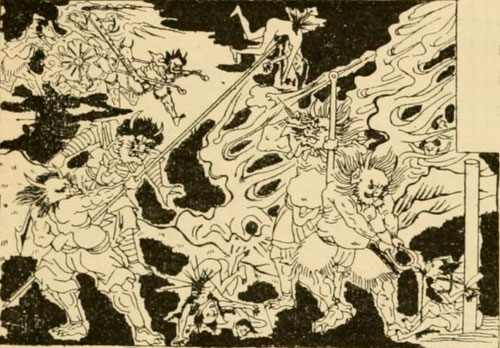

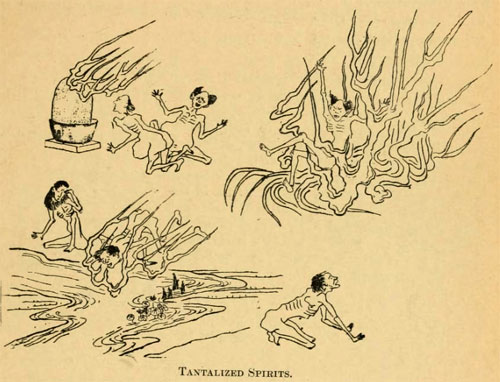

The Buddhist Hell

The antithesis to heaven is hell, which with its awful lessons looms large on the horizon of the Buddhists....The majority of the Lamas, however, and the laity, believe in the real material character of these hells and their torture.

The Buddhist hell (Naraka) is a true inferno situated in the bowels of the human earth like Hades, and presided over by the Indian Pluto, Yama, the king and judge of the dead, who however is himself finite and periodically tortured. Every day he is forced to swallow molten metal....

The Great Judgment is determined solely by the person's own deeds, and it is concretely pictured by the ordeal of scales, where the good deeds, as white pebbles, are weighed against the sins, as black counters, in balances, and the judge holds a mirror which reveals the soul in all its nakedness....The warders of hell drag the wicked before the king of hell, Yama, who says to them...'These thy evil deeds are not the work of thy mother, father, relatives, friends, advisers. Thou alone hast done them all; thou alone must gather the fruit.' And the warders of hell drag him to the place of torment, rivet him to red hot iron, plunge him in glowing seas of blood, torture him on burning coals, and he dies not till the last residue of his guilt has been expiated."...

Hell is divided into numerous compartments, each with a special sort of torture devised to suit the sins to be expiated. Only eight hells are mentioned in the older Buddhist books, but the Lamas and other "northern" Buddhists describe and figure eight hot and eight cold hells and also an outer hell (Pratyeka naraka), through which all those escaping from hell must pass without a guide. The Brahmanical hells are multiples of seven instead of eight; some of them bear the same names as the Buddhists, but they are not systematically arranged, and as the extant lists date no earlier than Manu, about 400 A.D., they are probably in great part borrowed from the Buddhists...

It has been suggested that Dante must have seen a Buddhist picture of these hells before writing his famous classic, so remarkable is the agreement between them...

Karma, or the ethical doctrine of retribution, is accepted as regards its general principle, even by such modern men of science as Huxley. It explains all the acts and events of one's life as the results of deeds done in previous existences, and it creates a system of rewards and punishments, sinking the wicked through the lower stages of human and animal existence, and even to hell, and lifting the good to the level of mighty kings, and even to the gods...

The most pessimistic view is of course taken of human life. It is made to be almost unalloyed misery, its striving, it perennially unsatisfied desire, its sensations of heat and cold, thirst and hunger, depression even by surfeiting with food, anxiety of the poor for their daily bread, of the farmer for his crops and cattle, unfulfilled desires, separation from relatives, subjection to temporal laws, infirmities of old age and disease, and accidents are amongst the chief miseries referred to...

Buddha's Conception of the Cause of Life and of Misery...

Buddha formulated his view of life into a twelve-linked closed chain called "the Wheel of Life or of 'Becoming'"...

The Chain then runs as follows:

"From the Ignorance (of the Unconscious Will) come Conformations. From Conformations comes Consciousness. From Consciousness comes Self-Consciousness. From Self-Consciousness come The Senses and Understanding. From the Senses and Understanding comes Contact. From Contact come Feeling. From Feeling comes Desire. From Desire come Indulgence, Greed, or Clinging (to Worldly Objects). From Clinging (to Worldly Objects) comes (Married or Domestic) Life. From (married) Life comes Birth (of an heir and Maturity of Life). From Birth (of an heir and Maturity of Life) come Decay and Death. From Decay and Death comes Re-birth with its attendant Sufferings. Thus all existence and suffering spring from the Ignorance (of the Unconscious Will)."

The varying nature and relationship of these formulae is noteworthy, some are resultants and some merely sequences; characteristic of Eastern thought, its mingling of science and poetry; its predominance of imagination and feeling over intellect; its curiously easy and naive transition from Infinite to Finite, from absolute to relative point of view.

But it would almost seem as if Buddha personally observed much of the order of this chain in his ethical habit of cutting the links which bound him to existence. Thus, starting from the link short of Decay and Death, he cut off his son (link 11), he cut off his wife (link 10), he cut off his worldly wealth and kingdom (link 9), then he cut off all Desire (link 8), with its "three fires." On this he attained Buddhahood, the Bodhi or "Perfect Knowledge" dispelling the Ignorance (Avidya), which lay at the root of Desire and its Existence. Nirvana, or "going out," thus seems to be the "going out" of the three Fires of Desire, which are still figured above him even at so late a stage as his "great temptation"; and this sinless calm, as believed by Professor Rhys Davids, is reachable in this life. On the extinction of these three fires there result the sinless perfect peace of Purity, Goodwill, and Wisdom, as the antitypes to the Three Fires, Lust, Ill-will, and Stupidity; while Parinirvana or Extinction of Life (or Becoming) was reached only with the severing of the last fetter or physical "Death," and is the "going out" of every particle of the elements of "becoming."...

As a philosophy, Buddhism thus seems to be an Idealistic Nihilism; an Idealism which, like that of Berkeley, holds that "the fruitful source of all error was the unfounded belief in the reality and existence of the external world"; and that man can perceive nothing but his feelings, and is the cause to himself of these. That all known or knowable objects are relative to a conscious subject, and merely a product of the ego, existing through the ego, for the ego, and in the ego, — though it must be remembered that Buddha, by a swinging kind of positive and negative mysticism, at times denies a place to the ego altogether. But, unlike Berkeley's Idealism, this recognition of the relativity and limitations of knowledge, and the consequent disappearance of the world as a reality, led directly to Nihilism, by seeming to exclude the knowledge, and by implication the existence, not only of a Creator, but of an absolute being.

As a Religion, Buddhism is often alleged to be theistic. But although Buddha gives no place to a First Cause in his system, yet, as is well known, he nowhere expressly denies an infinite first cause or an unconditioned Being beyond the finite; and he is even represented as refusing to answer such questions on the ground that their discussion was unprofitable. In view of this apparent hesitancy and indecision he may be called an agnostic.

In the later developments, the agnostic idealism of primitive Buddhism swung round into a materialistic theism which verges on pantheism, and where the second link of the Causal Chain, namely, Sanskara, comes closely to resemble the modi of Spinoza; and Nirvana, or rather Pari-Nirvana, is not different practically from the Vedantic goal: assimilation with the great universal soul...

Lamaist Metaphysics

After Buddha's death his personality soon became invested with supernatural attributes; and as his church grew in power and wealth his simple system underwent academic development, at the hands of votaries now enjoying luxurious leisure, and who thickly overlaid it with rules and subtle metaphysical refinements and speculations.

Buddha ceases even to be the founder of Buddhism, and is made to appear as only one of a series of (four or seven) equally perfect Buddhas who had "similarly gone" before, and hence called Tathagata, and implying the necessity for another "coming Buddha," who was called Maitreya, or "The Loving One."...

Buddha, it will be remembered, appears to have denied existence altogether. In the metaphysical developments after his death, however, schools soon arose asserting that everything exists (Sarvastivada), that nothing exists, or that nothing exists except the One great reality, a universally diffused essence of a pantheistic nature. The denial of the existence of the "Ego" thus forced the confession of the necessary existence of the Non-ego. And the author of the southern Pali text, the Milinda Panha, writing about 150 A.D., puts into the mouth of the sage Nagasena the following words in reply to the King of Sagala's query, "Does the all-wise (Buddha) exist?" "He who is the most meritorious does exist," and again "Great King! Nirwana is."

Thus, previous to Nagarjuna's school, Buddhist doctors were divided into two extremes: into a belief in a real existence and in an illusory existence; a perpetual duration of the Sattva and total annihilation. Nagarjuna chose a "middle way" (Mahyamika). He denied the possibility of our knowing that anything either exists or did not exist. By a sophistic nihilism he "dissolved every problem into thesis and antithesis and denied both." There is nothing either existent or non-existent, and the state of Being admits of no definition or formula...

The gist of the Avatansaka Sutra may be summarized as "The one true essence is like a bright mirror, which is the basis of all phenomena, the basis itself is permanent and true, the phenomena are evanescent and unreal; as the mirror, however, is capable of reflecting images, so the true essence embraces all phenomena and all things exist in and by it."

An essential theory of the Mahayana is the Voidness or Nothingness of things, Sunyata, evidently an enlargement of the last term of the Trividya formula, Anatma. Sakya Muni is said to have declared that "no existing object has a nature, whence it follows that there is neither beginning nor end — that from time immemorial all has been perfect quietude and is entirely immersed in Nirvana." But Sunyata, or, as it is usually translated, "nothingness" cannot be absolute nihilism for there are, as Mr. Hodgson tells us, "a Sunyata and a Maha-Sunyata. We are dead. You are a little Nothing; but I am a big Nothing. Also there are eighteen degrees of Sunyata. You are annihilated, but I am eighteen times as much annihilated as you." And the Lamas extended the degrees of "Nothingness" to seventy.

This nihilistic doctrine is demonstrated by The Three Marks and the Two Truths and has been summarized by Schlagintweit. The Three Marks are:

1. Parikalpita (Tib., Kun-tag) the supposition or error; unfounded belief in the reality of existence; two-fold error in believing a thing to exist which does not exist, and asserting real existence when it is only ideal.

2. Paratantra (T., Z'an-van) or whatever exists by a dependent or causal connexion, viz., the soul, sense, comprehension, and imperfect philosophical meditation.

3. Parinishpanna (T., Yon-grub) "completely perfect" is the unchangeable and unassignable true existence which is also the scope of the path, the summum bonum, the absolute.

The two Truths are Samvritisatya (T., Kun-dsa-bch'i-den-pa) The relative truth; the efficiency of a name or characteristic sign. And Paramarthasatya (Don-dam-pahi den-pa) the absolute truth obtained by the self-consciousness of the saint in self-meditations.

The world (or Samsara), therefore, is to be renounced not for its sorrow and pain as the Hinayana say, but on account of its unsatisfying unreality.

The idealization of Buddha's personality led, as we have just seen, to his deification as an omniscient and everlasting god; and traces of this development are to be found even in southern Buddhism. And he soon came to be regarded as the omnipotent primordial god, and Universal Essence of a pantheistic nature.

About the first century A.D. Buddha is made to be existent from all eternity (Anada). Professor Kern, in his translation of The Lotus of the True Law, which dates from this time, points out that although the theistic term Adi-Buddha or Primordial Buddha does not occur in that work, Sakya Muni is identified with Adi-Buddha in the words, "From the very beginning (adita eva) have I roused, brought to maturity, fully developed them (the innumerable Bodhisats) to be fit for their Bodhisattva position."

And with respect to the modes of manifestations of the universal essence, "As there is no limit to the immensity of reason and measurement to the universe, so all the Buddhas are possessed of infinite wisdom and infinite mercy. There is no place throughout the universe where the essential body of Vairocana (or other supreme Buddha, varying with different sects) is not present. Far and wide through the fields of space he is present, and perpetually manifested.

The modes in which this universal essence manifests itself are the three bodies (Tri-kaya), namely — (1) Dharma-kaya or Law-body, Essential Bodhi, formless and self-existent, the Dhyani Buddha, usually named Vairocana Buddha or the "Perfect Justification," or Adi-Buddha. (2) Sambhoga-kaya or Compensation-body, Reflected Bodhi, the Dhyani Bodhisats, usually named Lochana or "glorious"; and (3) Nirmana-kaya or Transformed-body, Practical Bodhi, the human Buddhas, as Sakya Muni.

Now these three bodies of the Buddhas, human and super-human, are all included in one substantial essence. The three are the same as one — not one, yet not different. When regarded as one the three persons are spoken of as Tathagata. But there is no real difference, these manifestations are only different views of the same unchanging substance...

This intense mysticism of the Mahayana led about the fifth century to the importation into Buddhism of the pantheistic idea of the soul (atman) and Yoga, or the ecstatic union of the individual with the Universal Spirit, a doctrine which had been introduced into Hinduism about 150 B.C. by Patanjali...

It is with this essentially un-Buddhistic school of pantheistic mysticism— which, with its charlatanism, contributed to the decline of Buddhism in India— that the Theosophists claim kinship. Its so-called "esoteric Buddhism" would better be termed exoteric, as Professor C. Bendall has suggested to me, for it is foreign to the principles of Buddha. Nor do the Lamas know anything about those spiritual mediums — the Mahatmas ("Koot Hoomi") — which the Theosophists place in Tibet, and give an important place in Lamaist mysticism. As we shall presently see, the mysticism of the Lamas is a charlatanism of a mean necromantic order, and does not even comprise clever jugglery or such an interesting psychic phenomenon as mesmerism, and certainly nothing worthy of being dignified by the name of "natural secrets and forces."...

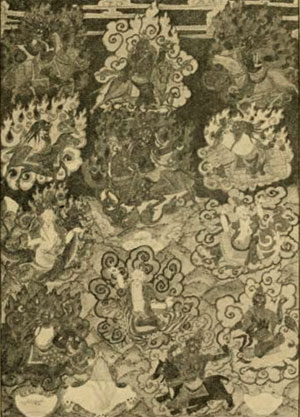

The extreme development of the Tantrik phase was reached with the Kala-cakra, which, although unworthy of being considered a philosophy, must be referred to here as a doctrinal basis. It is merely a coarse Tantrik development of the Adi-Buddha theory combined with the puerile mysticisms of the Mantrayana, and it attempts to explain creation and the secret powers of nature, by the union of the terrible Kali, not only with the Dhyani Buddhas, but even with Adi-Buddha himself. In this way Adi-Buddha, by meditation, evolves a procreative energy by which the awful Samvhara and other dreadful Dakkini-fiendesses, all of the Kali-type, obtain spouses as fearful as themselves, yet spouses who are regarded as reflexes of Adi-Buddha and the Dhyani Buddhas. And these demoniacal "Buddhas," under the names of Kala-cakra, Heruka, Achala, Vajra-vairabha, etc., are credited with powers not inferior to those of the celestial Buddhas themselves, and withal, ferocious and bloodthirsty; and only to be conciliated by constant worship of themselves and their female energies, with offerings and sacrifices, magic-circles, special mantra-charms, etc.

These hideous creations of Tantrism were eagerly accepted by the Lamas in the tenth century, and since then have formed a most essential part of Lamaism; and their terrible images fill the country and figure prominently in the sectarian divisions.

Afterwards was added the fiction of re-incarnate Lamas to ensure the political stability of the hierarchy.

HIGHLIGHTS FROM BOOK CONT'D HERE:

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.