Introduction For all the apparent materialism and mass mechanism of our present culture, we, far more than any of our fathers, live in a world of shadows.

-- G. K. Chesterton1

On January 1, 1900, most Americans greeted the twentieth century with the proud and certain belief that the next hundred years would be the greatest, the most glorious, and the most glamorous in human history. They were infected with a sanguine spirit. Optimism was rampant. A brazen confidence colored their every activity.

Certainly there was nothing in their experience to make them think otherwise. Never had a century changed the lives of men and women more dramatically than the nineteenth one just past. The twentieth century has moved fast and furiously, so that those of us who have lived in it feel sometimes giddy, watching it spin; but the nineteenth moved faster and more furiously still. Railroads, telephones, the telegraph, electricity, mass production, forged steel, automobiles, and countless other modern discoveries had all come upon them at a dizzying pace, expanding their visions and expectations far beyond their grandfathers’ wildest dreams.

It was more than unfounded imagination, then, that lay behind the New York World’s New Year’s prediction that the twentieth century would “meet and overcome all perils and prove to be the best that this steadily improving planet has ever seen.”2

Most Americans were cheerfully assured that control of man and nature would soon lie entirely within their grasp and would bestow upon them the unfathomable millennial power to alter the destinies of societies, nations, and epochs. They were a people of manifold purpose. They were a people of manifest destiny.

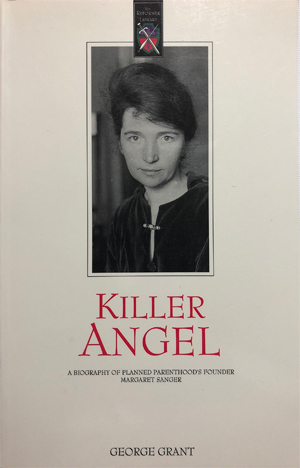

What they did not know was that dark and malignant seeds were already germinating just beneath the surface of the new century’s soil. Josef Stalin was a twenty-one-year-old seminary student in Tiflis, a pious and serene community at the crossroads of Georgia and Ukraine. Benito Mussolini was a seventeen-year-old student teacher in the quiet suburbs of Milan. Adolf Hitler was an eleven-year-old aspiring art student in the quaint upper Austrian village of Brannan. And Margaret Sanger was a twenty-year-old out-of-sorts nursing school dropout in White Plains, New York. Who could have ever guessed on that ebulliently auspicious New Year’s Day that those four youngsters would, over the span of the next century, spill more innocent blood than all the murderers, warlords, and tyrants of past history combined? Who could have ever guessed that those four youngsters would together ensure that the hopes and dreams and aspirations of the twentieth century would be smothered under the weight of holocaust, genocide, and carnage?

As the champion of the proletariat, Stalin saw to the slaughter of at least fifteen million Russian and Ukrainian kulaks. As the popularly acclaimed Il Duce, Mussolini massacred as many as four million Ethiopians, two million Eritreans, and a million Serbs, Croats, and Albanians. As the wildly lionized Fuhrer, Hitler exterminated more than six million Jews, two million Slavs, and a million Poles. As the founder of Planned Parenthood and the impassioned heroine of various feminist causes celebres, Sanger was responsible for the brutal elimination of more than thirty million children in the United States and as many as two and a half billion worldwide.

No one in his right mind would want to rehabilitate the reputations of Stalin, Mussolini, or Hitler. Their barbarism, treachery, and debauchery will make their names live in infamy forever. Amazingly though, Sanger has somehow escaped their wretched fate. In spite of the fact that her crimes against humanity were no less heinous than theirs, her place in history has effectively been sanitized and sanctified. In spite of the fact that she openly identified herself in one way or another with their aims, intentions, ideologies, and movements— with Stalin’s Sobornostic Collectivism, with Hitler’s Eugenic Racism, and with Mussolini’s Agathistic Fascism—her faithful minions have managed to manufacture an independent reputation for the perpetuation of her memory.

In life and death, the progenitor of the grisly abortion industry and the patron of the devastating sexual revolution has been lauded as a “radiant” and “courageous” reformer.3 She has been heralded by friend and foe alike as a “heroine,” a “champion,” a “saint,” and a “martyr."4 Honored by men as different and divergent as H. G. Wells and Martin Luther King, George Bernard Shaw and Harry Truman, Bertrand Russell and John D. Rockefeller, Albert Einstein and Dwight Eisenhower, this remarkable “killer angel” was able to secret away her perverse atrocities, emerging in the annals of history practically vindicated and victorious.5

That this could happen is a scandal of grotesque proportions.

And recently the proportions have only grown—like a deleterious kudzu or a rogue Topsy. Sanger has been the subject of adoring television dramas, hagiographical biographies, patronizing theatrical productions, and saccharine musical tributes. Though the facts of her life and work are anything but inspiring, millions of unwary moderns have been urged to find in them inspiration and hope. Myth is rarely dependent upon truth, after all.

Sanger’s rehabilitation has depended on writers, journalists, historians, social scientists, and sundry other media celebrities steadfastly obscuring or blithely ignoring what she did, what she said, and what she believed. It has thus depended upon a don’t-confuse-me-with-the-facts ideological tenacity unmatched by any but the most extreme of our modern secular cults.

This brief monograph is an attempt to set the record straight. It is an attempt to rectify that shameful distortion of the social, cultural, and historical record. It has no other agenda than to replace fiction with fact.

Nevertheless, that agenda necessarily involves stripping away all too many layers of dense palimpsests of politically correct revisionism. But that ought to be the honest historian’s central purpose anyway. Henry Cabot Lodge once asserted: “Nearly all the historical work worth doing at the present moment in the English language is the work of shoveling off heaps of rubbish inherited from the immediate past.”6

That then is the task of this book.

Of course, many would question the relevance of any kind of biographical or historical work at all. I cannot even begin to recount how many times a Planned Parenthood staffer has tried to deflect the impact of Sanger’s heinous record by dismissing it as “old news” or “ancient history” and thus irrelevant to any current issue or discussion. It is an argument that seems to sell well in the current marketplace of ideas. We have actually come to believe that matters and persons of present import are unaffected by matters and persons of past import.

We moderns hold to a strangely disjunctive view of the relationship between life and work—thus enabling us to nonchalantly separate a person’s private character from his or her public accomplishments. But this novel divorce of root from fruit, however genteel, is a ribald denial of one of the most basic truths in life: what you are begets what you do; wrong-headed philosophies stem from wrong-headed philosophers; sin does not just happen—it is sinners that sin.

Thus, according to the English historian and journalist Hilaire Belloc, “Biography always affords the greatest insights into sociology. To comprehend the history of a thing is to unlock the mysteries of its present, and more, to discover the profundities of its future.”7 Similarly, the inimitable Samuel Johnson quipped, “Almost all the miseries of life, almost all the wickedness that infects society, and almost all the distresses that afflict mankind, are the consequences of some defect in private duties.”8 Or, as E. Michael Jones has asserted, “Biography is destiny.”9

This is particularly true in the case of Margaret Sanger. The organization she founded, Planned Parenthood, is the oldest, largest, and best-organized provider of abortion and birth control services in the world.10 From its ignoble beginnings around the turn of the century, when the entire shoestring operation consisted of an illegal back-alley clinic in a shabby Brooklyn neighborhood staffed by a shadowy clutch of firebrand activists and anarchists,11 it has expanded dramatically into a multi-billion-dollar international conglomerate with programs and activities in 134 nations on every continent. In the United States alone, it has mobilized more than 20,000 staff personnel and volunteers along the front lines of an increasingly confrontational and vitriolic culture war. Today they handle the organization’s 167 affiliates and its 922 clinics in virtually every major metropolitan area, coast to coast.12 Boasting an opulent national headquarters in New York, a sedulous legislative center in Washington, opprobrious regional command posts in Atlanta, Chicago, Miami, and San Francisco, and officious international centers in London, Nairobi, Bangkok, and New Delhi, the Federation showed $23.5 million in earnings during fiscal year 1992, with $192.9 million in cash reserves and another $108.2 million in capital assets.13 With an estimated combined annual budget—including all regional and international service affiliates—of more than a billion dollars, Planned Parenthood may well be the largest and most profitable non-profit organization in history.14

The organization has used its considerable political, institutional, and financial clout to mainstream old-school left-wing extremism. It has weighed in with sophisticated lobbying, advertising, and back-room strong-arming to virtually remove the millennium-long stigma against child-killing abortion procedures and family-sundering socialization programs. Planned Parenthood thus looms like a Goliath over the increasingly tragic culture war.

Despite its leviathan proportions it is impossible to entirely understand Planned Parenthood’s policies, programs, and priorities apart from Margaret Sanger’s life and work. It was, after all, originally established to be little more than an extension of her life and world-view.”

Most of the material from this project has been drawn from research that I originally conducted for two comprehensive exposes of that vast institutional cash cow. Entitled Grand Illusions: The Legacy of Planned Parenthood, the first book has gone through twelve printing and two editions since it was first published in 1988?16 The second book, entitled Immaculate Deception: The Shifting Agenda of Planned Parenthood, details the remarkable changes the organization has made over the last decade.17 They gave wide exposure to the tragic proportions of Sanger’s saga. From the beginning of those massive projects, though, I felt that a shorter and more carefully focused biographical treatment was warranted. Little has changed in the interim-except that the monolithic reputations of Sanger and her frighteningly dystopic organization have only been further enhanced.

It is therefore long overdue that the truth be told. It is long overdue that the proper standing of Margaret Sanger in the sordid history of this bloody century be secured. To that end, this book is written.

You cannot help but notice, however, that it is a deliberately abbreviated tome-especially when it is compared to the breadth and depth of its wellspring, Grand Illusions and Immaculate Deception. Unpleasantries need to be accurately portrayed, but they need not be belabored. Caveats ought to be precise and to the point. Corrective counterblasts ought to be painstakingly careful, never crossing the all too fine line between informing and defiling the minds of readers.

Just as brevity and purpose are the heart and soul of wit, so they are the crux and culmination of true understanding. In light of this, it is my sincere prayer that true understanding will indeed be the end result of this brief but passionate effort.

Deus Vult.