by Rudyard Kipling

1901

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A report produced by the House of Lords has highlighted the use of children as spies in covert operations against terrorist organisations, gangs and drug dealers. The controversial practice, adopted by British police and intelligence agencies came to the attention of peers when the Home Office proposed extending the timeframe a person under 18 can be used for Covert Human Intelligence Source (CHIS) from one to four months.

A spokeswoman for prime minister, Theresa May, insisted that under-18s are used as intelligence sources only when “very necessary and proportionate” and according to a “very strict legal framework”. To date, no information has been released which ascertains how many children have been employed and implicated in this practice.

The spokeswoman cited preventing gang violence as an example of when children are used, as well as in operations aimed at tackling “county lines” drug dealing, which often involves using children to carry drugs around the country. While the law states that the risk of psychological distress or physical injury to the child needs to be evaluated before they are used as a source, there is little evidence or information about how this assessment is made.

Children are deemed to be useful for covert operations because they often attract less suspicion. A child can be used to provide information and to collect details about illegal activities.

However, the information being provided and collected may have limited benefit. According to the child development psychologist Jean Piaget, a child only begins to process logical thought and develop long-term memory retention between the ages of 12 and 18. Although recent evidence suggests that children have the ability to recall events accurately from a young age, this ability does not always translate into practice. Inaccurate reporting is common. Celine van Golde, a researcher at the University of Sydney, highlighted how inaccurate information can be provided by the child depending upon the tone of an interview or the way in which a question is asked.

Younger children may provide inaccurate information to security forces based on what they think the adults want to hear. A child also doesn’t necessarily have the same verbal communication skills as an adult. Information and nuance may be lost in translation. They might provide information that is inconsistent or incomplete.

And if the people the child is spying on do suspect them, the child may not have the cognitive ability or specialised training to detect when they are being fed false information. Not only does this place the child in considerable danger but it can have repercussions for the criminal investigation or security operation.

Quality, accurate information that can be acted upon quickly by security forces is vital in covert operations. A child doesn’t have the cognitive abilities to recall or collect the kind of nuanced information that is likely to offer significant benefit to the investigation. So if the child is only providing low-level intelligence or information, is it really worth risking their safety to get it?

The use of children as spies is morally inexcusable, even if a risk assessment has been made. When we use children to spy on criminal or terrorist organisations, we only compound the harm already committed. If it isn’t possible to appeal to the government to consider its moral obligations and duty to protect children, we can at least point out the practical pitfalls of using them like this.

-- Why using Children as Spies is Such a Bad Idea, by Michelle Jones (Post Doctoral Research Assistant, Anglia Ruskin University), and Dustin Johnson (Research Officer, Roméo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative, Dalhousie University, July 2018, theconversation.com

Children recruited to spy on drug dealers, gangs, terrorists and paedophiles have fewer safeguards when handled by investigators than those arrested for minor offences such as shoplifting, the high court has heard.

At a judicial review hearing at the Royal Courts of Justice, campaigners challenging the use of children as covert human intelligence sources (CHISs) argued the lack of safeguards violates children’s human rights and puts them at risk of severe harm.

Introducing the case against the Home Office on Tuesday, Caoilfhionn Gallagher QC, acting for Just for Kids Law, told Mr Justice Michael Supperstone that safeguards for children recruited as CHISs were inadequate.

“This case concerns children who may be recruited and deployed as CHIS in the most extreme circumstances,” Gallagher said, referring in particular to one case revealed in a House of Lords debate of a 17-year-old girl recruited to spy on a man who was selling her for sex.

Gallagher said: “A justification put forward is that some children are involved in or in close proximity to serious crimes which they could as a covert source help police to investigate and prosecute.

“That justification also demonstrates the acute need for stringent safeguards: keeping a child close to serious crimes may serve a compelling public interest, but it would appear to be antithetical to the child’s own interests.”

Seventeen children have been recruited as covert sources since January 2015 – including one just 15 at the time – according to figures released by the investigatory powers commissioner in March.

The powers under which they are used have existed for nearly two decades, but they came to light only last summer after a House of Lords committee raised the alarm over proposals to make recruitment and deployment easier.

Ministers had sought to increase the length of time that child spies could be deployed before re-authorisation from one month to four, and to broaden the range of people who could act as an “appropriate adult” when being interviewed with police. The new rules came into effect shortly after.

Just for Kids Law’s judicial review hinges on a claim that the rules governing the use of child spies fail to comply with the home secretary’s obligations to comply with article 8 of the Human Rights Act -– guaranteeing children’s right to a private or family life -– and article 3.1 of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child – stipulating that the interests of the child should be a top priority in all decisions and actions that affect them.

Gallagher warned that the extension of the length of time a child spy could be authorised had come about for the “administrative convenience of the authorities concerned.” Because the orders involve covert operations, officers are not required to check with other agencies about vulnerability, histories of domestic abuse or mental health issues of the child spies.

“The decision is made in a very closed circle,” she said.

The court heard evidence from Neil Woods, a former police officer who spent years undercover investigating drugs gangs, that such work posed the risk of severe physical and psychological harm to young people.

In a written statement read out in court, Woods said he had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of his experiences undercover with drugs gangs, which included proximity to extreme violence, including torture and maimings of those considered to be working with police.

“I developed the ability to suppress my emotions at times of great stress when I was witnessing very grave things,” Woods said in his statement.

“It causes me great concern that a child could be asked to maintain a lie for any length of time and suffer the psychological harm that I have suffered … I question the legitimacy in allowing police to recruit child spies at a time when police are just beginning to recognise the lasting harm caused to adults in doing the same thing.”

Sir James Eadie QC, responding on behalf of the home secretary, emphasised the many layers of approvals and safeguards involved in recruiting children as CHISs.

The hearing lasted one day and Supperstone reserved his judgment, which he will hand down at a later date.

-- Child spies used by police at risk of severe harm, high court told: Campaigners say there are not enough safeguards to protect children in covert operations, by Damien Gayle, June 2019, Theguardian.com

On the occasion of launching his Children’s Fund in 1995, Nelson Mandela said ”There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.” On that basis an insight into the soul of British society is provided by the recent revelation that the United Kingdom government recruits and uses children (persons under the age of 18) as spies, or domestic covert human intelligence sources (CHIS), as they are formally known. A July 12 report by a House of Lords’ Committee has put this little-known and controversial practice under the spotlight. Politicians and NGOs have condemned it. A former cabinet minister has described it as “morally repugnant”; the shadow home secretary called for an immediate end to it; Amnesty International described it as “shocking and unacceptable”; and Rights Watch (UK) said the practice “runs directly counter to the Government’s human rights obligations.”

The U.K. government’s position is summarized in its July 3 letter to the Committee. It explains that while using children as spies is currently only authorized in “very small numbers” (although statistics are not kept of how many), there is increasing scope for their use in preventing and prosecuting such serious crimes as “terrorism, gang violence, county lines drug offences and child sexual exploitation.” The government has recently made an Order -– the Regulation of Investigatory Powers (Juveniles) (Amendment) Order 2018 (the 2018 Order) –- so as to extend, from one month to four months, the period for which child CHISs can be authorized at a time. That time extension is what led the Committee to consider the issue of child spies, although (as we explain below) they considered a number of other related matters too.

We pause here to note that here are two key questions regarding the issue of child spies. First: Is the use of child spies justifiable and appropriate? Second: And, if so, what legal safeguards are necessary to ensure that the best interests of children are considered and protected in making decisions concerning such use? Both of these questions should be analyzed by reference to the rights of children as well as law enforcement and security priorities. Before we consider these questions, here is a little more legal context regarding the use of child spies.

• Part II of the U.K.’s Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA) provides for a statutory authorization regime in respect to surveillance and the use of CHISs. An authorization is a necessary pre-condition to the lawfulness of proposed surveillance or use.

• Section 29 of RIPA also provides that authorizations for the use of CHISs are, in general, only to be granted where (1) they are considered necessary on grounds including “the interests of national security,” “the purpose of preventing or detecting crime or of preventing disorder,” “the interests of the economic well-being of the United Kingdom,” “the interests of public safety,” “the purpose of protecting public health,” and “the purpose of assessing or collecting any tax, duty, levy or other imposition, contribution or charge payable to a government department”; and (2) the authorised conduct or use is considered proportionate to what is sought to be achieved by that conduct or use. Only a designated person, identified in Schedule 1 of RIPA and relevant secondary legislation, may grant such an authorisation.

• The Regulation of Investigatory Powers (Juveniles) Order 2000 (the 2000 Order) provides for additional requirements that must be satisfied in respect of the authorization of CHISs under the age of 18.

• The 2018 Order, on which the Committee has commented, amends the 2000 Order by extending the duration of an authorization from one to four months (see below).

• The following additional requirements distinguish the authorization of child CHISs from adult CHISs:

1. Children under the age of 16 must not be used to spy on their parents or any other person who has parental responsibility for them (article 3, 2000 Order). There is no prohibition on the use of older children for this purpose.

2. Where children under the age of 16 are used as CHISs, an “appropriate adult” (e.g. parent) must be present at all meetings between the CHIS and the person representing any relevant investigating authority (in other words, the “handler” of the CHIS) (article 4, 2000 Order). There is no requirement that an appropriate adult be present in meetings with an older child CHIS.

3. A risk assessment must be undertaken into the proposed use of a child CHIS (article 5). It must identify and evaluate any risk of “physical injury” and “psychological distress” to the CHIS (article 5(a)). The person granting the authorization must be satisfied that the risks identified are justified and that they have been properly explained to, and understood by, the CHIS (article 5(b)). Where the proposed use is in respect of a parental relationship, particular consideration must be given to whether authorization would be justified (article 5(c)). But article 5 does not expressly incorporate any requirement to have regard to wider risks beyond those relating to physical injury or psychological distress. Lord Simon Haskel noted some of these in the Committee: “There is the risk of being beaten up, of sexual exploitation, of reprisals, as well as the impact on their education and on their mental health.” Nor does Article 5 expressly refer to, let alone give particular weight to, the best interests of the child, which is a fundamental part of the law. As the U.K. Supreme Court has recently noted: Article 3(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which the U.K. has ratified provides, “In all actions concerning children … the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” (R (MM (Lebanon) v Home Secretary [2017] 1 WLR 771, at [45]). In that case the Court also cited a judgment of the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights which explains, “there is a broad consensus, including in international law, in support of the idea that in all decisions concerning children, their best interests are of paramount importance. Whilst alone they cannot be decisive, such interests certainly must be afforded significant weight.” (Jeunesse v The Netherlands (2014) 60 EHRR 17, [109]). Nor does Article 5 provide express guidance for deciding whether the particular risk of physical injury or psychological distress to a child is justified by the particular law enforcement or security matter. As Lord Haskel put it: “Is it right to put one juvenile in jeopardy for the greater good?”

4. The maximum duration for an authorization for a child CHIS is now four months (article 6, 2000 Order as amended by the 2018 Order), although an authorization can be renewed upon expiry. This represents an increase from the previous maximum period of one month. It contrasts with the position in respect of adult CHISs, where an authorization can last for up to 12 months at a time.

In its report, the Committee’s main focus was on the extension of the duration of authorizations but, it expressed a number of general concerns in relation to the existing regime; these were also raised in the debate. For example, it referred to the risk that those granting authorization may not be well placed to assess the risks to the mental health of juvenile CHISs; the problems of ensuring a consistent approach between different authorizing authorities, and that the government had failed to explain “how the authorising officer is supposed to weigh the intelligence benefits against the potential negative impact on juvenile sources.”

Although the issue of child spies may end up before the parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights for further investigation and consideration, the government has not yet given any commitment to reconsider whether the use of children as CHISs -– both in principle and as a matter of practice –- is consistent with its legal obligations, including under international law. Thus, as we have already noted: the U.K. is a party to the CRC. The CRC defines a child as every human being under the age of 18 years (except in those cases where the domestic law applicable to the child has an earlier age of majority). In addition to the “best interests” obligation under Article 3(1), Article 19 requires the U.K. to take all appropriate action to protect children from all forms of violence, injury, abuse, maltreatment and exploitation. Article 32 also recognizes the right of a child to be protected from performing work that is likely to be “harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.” Articles 33 to 36 contain express prohibitions to ensure children are protected from drug abuse, sexual abuse, and other forms of exploitation prejudicial to their welfare. These provisions of the CRC are also relevant to the construction and development of the human rights of children under relevant provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights, which is given effect in domestic law in the U.K. through the Human Rights Act 1998.

In our view, the U.K. government should commit to reviewing the existing use of child spies because it is questionable, to say the least, whether that existing use is consistent with its international obligations under the CRC and its domestic human rights commitments. Although it might be necessary, in extreme cases, to use child spies: legal (and other) safeguards must be further developed so as to ensure that the best interests of the potential child spy are holistically reviewed and given primary consideration. For example:

First, although the government has said that child spies are used in “very small numbers” section 29 of RIPA (see above) contemplates children being used as CHISs in a very broad range of circumstances. It is questionable whether this broad range should apply equally to adult and child CHISs. The special interests and needs of children should be recognized and taken into account in deciding the range of circumstances in which they may be used as spies.

Second, the interests of the child must be properly and holistically evaluated in any decision to authorize the use of a child as a CHIS. Article 5 of the 2000 Order does not provide for an adequate risk assessment procedure. For example, those granting an authorization are not expressly directed to treat the best interests of the child as a “primary consideration.” That is an important guiding principle in evaluating the risks to a child’s interests and deciding whether those risks can be justified in a particular context. Similarly, authorizing officers are not required to have regard to risks beyond those relating to physical injury and psychological distress, including the broader impact on a child’s social and educational development. Moreover, it is unlikely that the statutory risk assessment process can operate adequately in practice without expert input to assist the decision-maker in understanding the likely impact of both the proposed use on the present well-being of the child concerned as well as the potential future or long-term impact on former child spies.

Third, there is a dubious distinction in the 2000 Order between children under the age of 16 and older children. As noted above, the CRC defines every person under the age of 18 as a child, although it recognizes that the needs of children change with their age. We do not see any good reason for depriving CHISs aged over 16 of the assistance of an appropriate adult in the context of discussions with their handlers. Similarly, it is unclear why the government considers that it is potentially appropriate for a 16-year-old to be asked to spy on his parents, in circumstances where it accepts that it is never appropriate for a 15-year-old to be asked to do so.

-- The Use of Child Spies by the UK, by Shaheed Fatima Q.C. and Hanif Mussa, July 2018, justsecurity.org

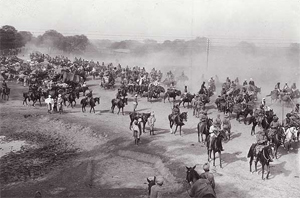

Children in the military are children (defined by the Convention on the Rights of the Child as people under the age of 18) who are associated with military organisations, such as state armed forces and non-state armed groups. Throughout history and in many cultures, children have been involved in military campaigns. For example, thousands of children participated on all sides of the First World War and the Second World War. Children may be trained and used for combat, assigned to support roles such as porters or messengers, or used for tactical advantage as human shields or for political advantage in propaganda.

Children are easy targets for military recruitment due to their greater susceptibility to influence compared to adults. Some are recruited by force while others choose to join up, often to escape poverty or because they expect military life to offer a rite of passage to maturity.

Child recruits who survive armed conflict frequently suffer psychiatric illness, poor literacy and numeracy, and behavioral problems such as heightened aggression, leading to a high risk of poverty and unemployment in adulthood. Research in the UK and US has also found that the enlistment of adolescent children, even when they are not sent to war, is accompanied by a higher risk of attempted suicide, stress-related mental disorders, alcohol abuse, and violent behavior.

A number of treaties have sought to curb the participation of children in armed conflicts. According to Child Soldiers International these agreements have helped to reduce child recruitment, but the practice remains widespread and children continue to participate in hostilities around the world. Some economically powerful nations continue to rely on military recruits aged 16 or 17, and the use of younger children in armed conflict has increased in recent years as militant movements and the groups fighting them recruited children in large numbers...

Since the adoption in 2000 of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC) the global trend has been towards restricting armed forces recruitment to adults aged 18 or over, known as the Straight-18 standard. Most states with armed forces have opted in to OPAC, which also prohibits states that still recruit children from using them in armed conflict.

Nonetheless, Child Soldiers International reported in 2018 that children under the age of 18 were still being recruited and trained for military purposes in 46 countries; of these, most recruit from age 17, fewer than 20 recruit from age 16, and an unknown, smaller number, recruit younger children. States that still rely on children to staff their armed forces include the world's three most populous countries (China, India, and the United States) and the most economically powerful (all G7 countries apart from Italy and Japan). The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and others have called for an end to the recruitment of children by state armed forces, arguing that military training, the military environment, and a binding contract of service are not compatible with children's rights and jeopardize healthy development during adolescence.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates hired child soldiers from Sudan (especially from Darfur) to fight against Houthis during the Yemeni Civil War (2015–present)...

In 2003 P. W. Singer of the Brookings Institution estimated that child soldiers participate in about three-quarters of ongoing conflicts. In the same year the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) estimated that most of these children were aged over 15, although some were younger.

Today, due to the widespread military use of children in areas where armed conflict and insecurity prevent access by UN officials and other third parties, it is difficult to estimate how many children are affected. In 2017 Child Soldiers International estimated that several tens of thousands of children, possibly more than 100,000, were in state- and non-state military organisations around the world, and in 2018 the organisation reported that children were being used to participate in at least 18 armed conflicts.

Despite children's physical and psychological underdevelopment relative to adults, there are many reasons why state- and non-state military organisations seek them out. Cited examples include:

• Peter W. Singer has suggested that the global proliferation of light automatic weapons, which children can easily handle, has made the use of children as direct combatants more viable.

• Roméo Dallaire has pointed to the role of overpopulation in making children a cheap and accessible resource for military organisations.

• Roger Rosenblatt has suggested that children are more willing than adults to fight for non-monetary incentives such as religion, honour, prestige, revenge and duty.

• Several commentators, including Bernd Beber, Christopher Blattman, Dave Grossman, Michael Wessels, and McGurk and colleagues, have argued that since children are more obedient and malleable than adults, they are easier to control, deceive and indoctrinate.

• David Gee and Rachel Taylor have found that in the UK, the army finds it easier to attract child recruits starting from age 16 than adults from age 18, particularly those from poorer backgrounds.

• Some leaders of armed groups have claimed that children, despite their underdevelopment, bring their own qualities as combatants to a fighting unit, often being remarkably fearless, agile and hardy.

While some children are forcibly recruited, deceived, or bribed into joining military organisations, others join of their own volition. There are many reasons for this. In a 2004 study of children in military organisations around the world, Rachel Brett and Irma Specht pointed to a complex of factors that incentivise enlisting, particularly:

• Background poverty including a lack of civilian education or employment opportunities

• The cultural normalization of war

• Seeking new friends

• Revenge (for example, after seeing friends and relatives killed)

• Expectations that a "warrior" role provides a rite of passage to maturity

The following testimony from a child recruited by the Cambodian armed forces in the 1990s is typical of many children's motivations for joining up:I joined because my parents lacked food and I had no school... I was worried about mines but what can we do—it's an order [to go to the front line]. Once somebody stepped on a mine in front of me—he was wounded and died... I was with the radio at the time, about 60 metres away. I was sitting in my hammock and saw him die... I see young children in every unit... I'm sure I'll be a soldier for at least a couple of more years. If I stop being a soldier I won't have a job to do because I don't have any skills. I don't know what I'll do...

The scale of the impact on children was first acknowledged by the international community in a major report commissioned by the UN General Assembly, Impact of Armed Conflict on Children (1996), which was produced by the human rights expert Graça Machel. The report was particularly concerned with the use of younger children, presenting evidence that many thousands of children were being killed, maimed, and psychiatrically injured around the world every year.

Since the Machel Report further research has shown that child recruits who survive armed conflict face a markedly elevated risk of debilitating psychiatric illness, poor literacy and numeracy, and behavioural problems. Research in Palestine and Uganda, for example, has found that more than half of former child soldiers showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and nearly nine in ten in Uganda screened positive for depressed mood. Researchers in Palestine also found that children exposed to high levels of violence in armed conflict were substantially more likely than other children to exhibit aggression and anti-social behaviour. The combined impact of these effects typically includes a high risk of poverty and lasting unemployment in adulthood.

Further harm is caused when child recruits are detained by armed forces and groups, according to Human Rights Watch. Children are often detained without sufficient food, medical care, or under other inhumane conditions, and some experience physical and sexual torture. Some are captured with their families, or detained due to the activity of one of their family members. Lawyers and relatives are frequently banned from any court hearing.

Other research has found that the enlistment of children, including older children, has a detrimental impact even when they are not used in armed conflict until they reach adulthood. Military academics in the US have characterized military training (at all ages) as "intense indoctrination" in conditions of sustained stress, the primary purpose of which is to establish the unconditional and immediate obedience of recruits. The academic literature has found that adolescents are more vulnerable than adults to a high-stress environment, such as that of initial military training, particularly those from a background of childhood adversity. Enlistment, even before recruits are sent to war, is accompanied by a higher risk of attempted suicide in the US, higher risk of mental disorders in the US and the UK, higher risk of alcohol misuseand higher risk of violent behaviour, relative to recruits' pre-enlistment background. Military settings are also characterised by elevated rates of bullying and sexual harassment.

Military recruitment practices have also been found to exploit the vulnerabilities of children in mid-adolescence. Specifically, evidence from Germany, the UK and the US has shown that recruiters disproportionately target children from poorer backgrounds using marketing that omits the risks and restrictions of military life. Some academics have argued that marketing of this kind capitalises on the psychological susceptibility in mid-adolescence to emotionally-driven decision-making.

-- Children in the military, by Wikipedia

Kim (Kimball O'Hara) [David Macdonald?] is the orphaned son of an Irish soldier (Kimball O'Hara Sr., a former colour sergeant and later an employee of an Indian railway company) and a poor Irish mother (a former nanny in a colonel's household) who have both died in poverty. Living a vagabond existence in India under British rule in the late 19th century, Kim earns his living by begging and running small errands on the streets of Lahore. He occasionally works for Mahbub Ali, a Pashtun horse trader who is one of the native operatives of the British secret service. Kim is so immersed in the local culture that few realise he is a white child, although he carries a packet of documents from his father entrusted to him by an Indian woman who cared for him.

Kim befriends an aged Tibetan lama who is on a quest to free himself from the Wheel of Things by finding the legendary ″River of the Arrow″. Kim becomes his chela, or disciple, and accompanies him on his journey. On the way, Kim incidentally learns about parts of the Great Game and is recruited by Mahbub Ali to carry a message to the head of British intelligence in Umballa. Kim's trip with the lama along the Grand Trunk Road is the first great adventure in the novel.

By chance, Kim's father's regimental chaplain identifies Kim by his Masonic certificate, which he wears around his neck, and Kim is forcibly separated from the lama. The lama insists that Kim should comply with the chaplain's plan because he believes it is in Kim's best interests, and the boy is sent to a top English school in Lucknow. The lama, a former abbot, funds Kim's education.

Throughout his years at school, Kim remains in contact with the holy man he has come to love. Kim also retains contact with his secret service connections and is trained in espionage (to be a surveyor) while on vacation from school by Lurgan Sahib, a sort of benevolent Fagin, at his jewellery shop in Simla. As part of his training, Kim looks at a tray full of mixed objects and notes which have been added or taken away, a pastime still called Kim's Game, also called the Jewel Game.

After three years of schooling, Kim is given a government appointment so that he can begin to participate in the Great Game. Before this appointment begins, however, he is granted a much-deserved break. Kim rejoins the lama and at the behest of Kim's superior, Hurree Chunder Mookherjee [Sarat Chandra Das], they make a trip to the Himalayas so Kim can investigate what some Russian intelligence agents are doing.

Kim obtains maps, papers and other important items from the Russians, who are working to undermine British control of the region. Mookherjee befriends the Russians undercover, acting as a guide, and ensures that they do not recover the lost items. Kim, aided by some porters and villagers, helps to rescue the lama.

The lama realises that he has gone astray. His search for the River of the Arrow should be taking place in the plains, not in the mountains, and he orders the porters to take them back. Here Kim and the lama are nursed back to health after their arduous journey. Kim delivers the Russian documents to Hurree, and a concerned Mahbub Ali comes to check on Kim.

The lama finds his river and is convinced he has achieved Enlightenment.

-- Kim (novel), by Wikipedia

We find [Sarat Chandra Das] making an appearance in the caricature of an English-educated Bengali spy in the figure of Hurree Chunder Mukherjee [R17] [Hurree Babu] [Babu] [Hakim] [The Seeker] in Rudyard Kipling’s famous novel Kim.

-- Meet Sarat Chandra Das: The spy who came in from the cold of Tibet and wrote a book about it, by Parimal Bhattacharya

The stories about Sarat Chandra Das are quite well known in Tibet, even children being familiar with them; but there are few who know him by his real name, for he goes by the appellation of the ‘school bābū’ (school-master).

-- Three Years in Tibet, by Shramana Ekai Kawaguchi

The ruin thus brought about by the Babu's visit extended also to the unfortunate Lama's relatives, the governor of Gyantsé (the Phal Dahpön) and his wife (Lha-cham), whom he had persuaded to befriend Sarat C. Das. These two were cast into prison for life, and their estates confiscated, and several of their servants were barbarously mutilated, their hands and feet were cut off and their eyes gouged out, and they were then left to die a lingering death in agony, so bitterly cruel was the resentment of the Lamas against all who assisted the Babu in this attempt to spy into their sacred city.

-- Lhasa and Its Mysteries: With a Record of the Expedition of 1903-1904, by Laurence Austine Waddell

CONTENTS:

• CHAPTER I

• CHAPTER II

• CHAPTER III

• CHAPTER IV

• CHAPTER V

• CHAPTER VI

• CHAPTER VII

• CHAPTER VIII

• CHAPTER IX

• CHAPTER X

• CHAPTER XI

• CHAPTER XII

• CHAPTER XIII

• CHAPTER XIV

• CHAPTER XV