Chapter 5: Ramsay's Ur-Tradition

When D. P. Walker wrote about "ancient theology" [The Ancient Theology: Studies in Christian Platonism from the Fifteenth to the Eighteenth Century (London, Duckworth, 1972), by Daniel Pickering Walker (1914-1985)] or prisca theologia, he firmly linked it to Christianity and Platonism (Walker 1972). On the first page of his book, Walker defined the term as follows:

By the term "Ancient Theology" I mean a certain tradition of Christian apologetic theology which rests on misdated texts. Many of the early Fathers, in particular Lactantius, Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius, in their apologetic works directed against pagan philosophers, made use of supposedly very ancient texts: Hermetica, Orphica, Sibylline Prophecies, Pythagorean Carmina Aurea, etc., most of which in fact date from the first four centuries of our era. [100-400 A.D.] These texts, written by the Ancient Theologians Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Pythagoras, were shown to contain vestiges of the true religion: monotheism, the Trinity, the creation of the world out of nothing through the Word, and so forth. It was from these that Plato [428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC)] took the religious truths to be found in his writings. [???!!!] (Walker 1972:1)

By the term "Ancient Theology"1 [i.e. prisca theologica, a term which I regret having launched, since no one, including myself, is quite sure how to pronounce it. The main recent works on this subject are: F.A. Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, London, 1964; J. Dagens, 'Hermetisme et Cabale en France, de Lefevre d'Etaples a Bossuet', in Revue de litterature comparee, annee 35, Paris, 1961, pp. 5-16; Charles B. Schmitt, 'Perennial Philosophy: from Agostino Steuco to Leibniz', in Journal of the History of Ideas, xxvii, 1966, pp. 505-32.] I mean a certain tradition of Christian apologetic theology which rests on misdated texts. Many of the early Fathers, in particular Lactantius, Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius, in their apologetic works directed against pagan philosophers, made use of supposedly very ancient texts: Hermetica, Orphica2 [v. infra, pp. 14 seq.], Sibylline Prophecies,3 [Oracula Sybyllina, ed. J. Geffcken, Leipzig, 1902; cf. F.A. Yates, Bruno, p. 8, n. 4.] Pythagorean Carmina Aurea,4 [Les Vers d'or pythagoriciens, ed. P.C. Van der Horst, Leiden, 1932; The Pythagorean Texts of the Hellenistic Period, ed. H. Thesleff, Abo, 1965; Hieroclis in Aureum Pythagoreorum Carmen Commentarius, ed. F.G. A. Mullachius, Hildesheim, 1971; M.T. Cardini, Pitagorici Testimonianze e Frammenti, Firenze, 1958, 3 vols.] etc., most of which in fact date from the first four centuries of our era. [100-400 A.D.] These texts, written by the Ancient Theologians Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Pythagoras, were shown to contain vestiges of the true religion: monotheism, the Trinity, the creation of the world out of nothing through the Word, and so forth. It was from these that Plato [428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC)] took the religious truths to be found in his writings.

-- The Ancient Theology: Studies in Christian Platonism from the Fifteenth to the Eighteenth Century, by D.P. Walker, 1972:1)

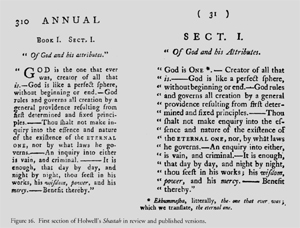

Walker described a revival of such "ancient theology" in the Renaissance and in "platonizing theologians from Ficino to Cudworth" who wanted to "integrate Platonism and Neoplatonism into Christianity, so that their own religious and philosophical beliefs might coincide" [!!!](p. 2). After the debunking of the genuineness and antiquity of the texts favored by these ancient theologians, the movement ought to have died; but Walker detected "a few isolated survivals" such as Athanasius Kircher, Pierre-Daniel Huet, and the Jesuit figurists of the French China mission (p. 194). For Walker the last Mohican of this movement, so to say, is Chevalier Andrew Michael RAMSAY (1686-1743), whose views are described in the final chapter of The Ancient Theology. But seen through the lens of our concerns here, one could easily extend this line to various figures in this book, for example, Jean Calmette, John Zephaniah Holwell, Abbe Vincent Mignot, Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, Guillaume Sainte-Croix, and also to William Jones (App 2009).

Ur-Traditions

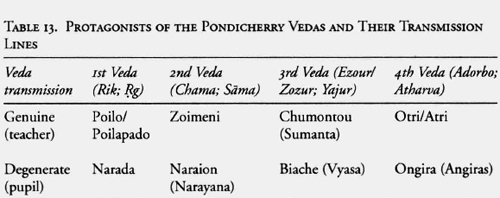

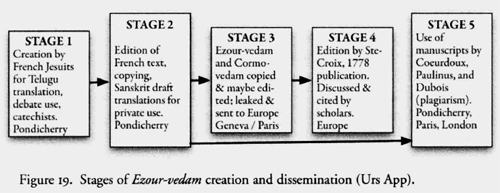

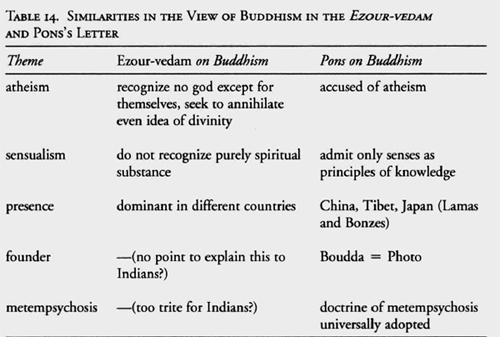

To better understand such phenomena we have to go beyond the narrow confines of the Christian God and Platonism. There are many movements that link themselves to some kind of "original," "pure," "genuine" teaching, claim its authority, use it to criticize "degenerate" accretions, and attempt to legitimize their "reform" on its basis. Such links can take a variety of forms. In Chapter 4 we saw how in the eighth and ninth centuries the Buddhist reform movement known as Zen cooked up a lineage of "mind to mind" transmission with the aim of connecting the teaching of the religion's Indian founder figure, Buddha, with their own views. The tuned-up and misdated Forty-Two Sections Sutra that ended up impressing so many people, including its first European translator de Guignes, was one (of course unanticipated) outcome of this strategy. Such "Ur-tradition" movements, as I propose to call them, invariably create a "transmission" scenario of their "original" teaching or revelation; in the case of Zen this consisted in an elaborate invented genealogy with colorful transmission figures like Bodhidharma and "patriarchs" consisting mostly of pious legends. Such invented genealogies and transmissions are embodied in symbols and legends emphasizing the link between the "original" teaching and the movement's doctrine. "Genuine," "oldest" texts are naturally of central importance for such movements, since they tend to regard the purity of teaching as directly proportional to its closeness to origins.

A common characteristic of such "Ur-tradition" movements is a tripartite scheme of "golden age," "degeneration," and "regeneration." The raison d'etre of such movements is the revival of a purportedly most ancient, genuine, "original" teaching after a long period of degeneration. Hence their need to define an "original" teaching, establish a line of its transmission, identify stages and kinds of degeneration, and present themselves as the agent of "regeneration" of the original "ancient" teaching. Such need often arises in a milieu of doctrinal rivalry or in a crisis, for example, when "new" religions or reform movements want to establish and legitimize themselves or when an established religion is threatened by powerful alternatives.

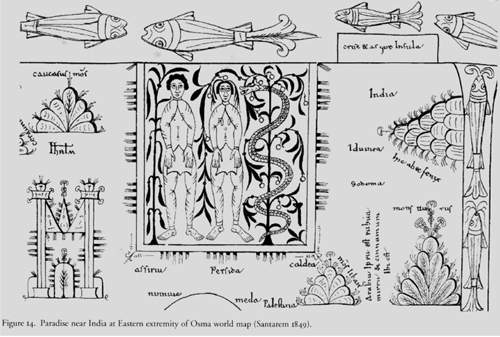

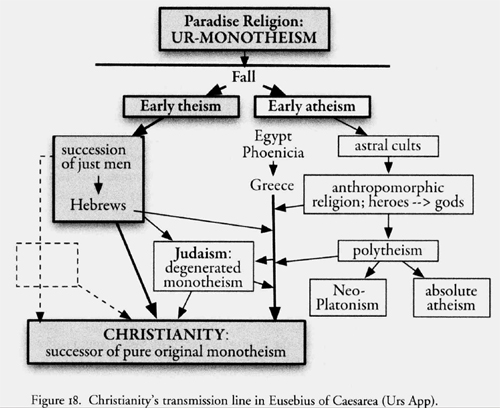

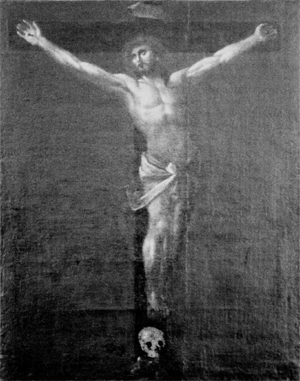

When young Christianity evolved from a Jewish reform movement and was accused of being a "new religion" and an invention, ancient connections were needed to provide legitimacy and add historical weight to the religion. The adoption of the Hebrew Bible as "Old Testament," grimly opposed by some early Christians, linked the young religion and its "New Testament" effectively to the very creation of the world, to paradise, and to the Ur-religion of the first humans in the golden age. Legends, texts, and symbols were created to illustrate this "Old-to-New" link. For example, the savior's cross on Golgotha had to get a pedigree connecting it to the Hebrew Bible's paradise tree; and the original sinner Adam's skull had to be brought via Noah's ark to Palestine in order to get buried on the very hill near Jerusalem where Adam's original sin eventually got expunged by the New Testament's "second Adam" on the cross (Figure 11). Theologians use the word "typology" for such attempts to discover Christian teachings or forebodings thereof in the Old Testament.

Similar links to an "oldest," "purest," and "original" teaching are abundant not only in the history of religions but also, for example, in freemasonry and various "esoteric" movements. They also tend to invent links to an original "founder," "ancient" teachings and texts, lineages, symbols of the original doctrine and its transmission, eminent transmitter figures ("patriarchs"), and so on; and they usually criticize the degeneration of exactly those original and pure teachings that they claim to resuscitate. In such schemes the most ancient texts, symbols, and objects naturally play important roles, particularly if they seem mysterious: pyramids, hieroglyphs, runic letters, ancient texts buried in caves, and divine revelations stored on golden tablets in heaven or in some American prophet's backyard ...

Figure 11. Adam's skull underneath the cross. Collection of Drs. Valerio and Adriana Pozza, Padova, Italy.

In premodern Europe such "original" teachings were usually associated with Old Testament heroes who had the function of transmitters. A typical example that shows how various ancient religions were integrated in a genealogy linking them to primeval religion as well as its fulfillment in Christianity is Jacques Boulduc's De Ecclesia ante legem ("On the Church before the [Mosaic] Law") of 1626. Boulduc shows in a table how the extremely long lifespans of the patriarchs facilitated transmission: for example, Adam lived for 930 years and could instruct his descendants in person until his sixth-generation Ur-nephew Lamech, Noah's father, was fifty-six years old. Adam's son Seth was 120 years old when the first priestly functions were instituted; 266 years old when his son Enos first offered prayers in a dedicated house; and 800 years old when he took over the supreme pontificate of the "church before the law" at Adam's untimely death (1630:148-49). In the second book, Boulduc shows that "all philosophers, both of Greece and of other regions, have their origin in the descendants of the prophet Noah" (p. 271) and includes in this transmission lineage even the "wise rather than malefic Persian magi [Magos Persas non maleficos, sed sapientes]," Egyptian prophets, Gallic druids, the "naked sages of India [Indis Gymnosophistae]," etc. (p. 273). Boulduc took special care to document through numerous quotations from ancient sources that the wise men who were variously called Semai, Semni, Semanai, Semnothei, and Samanaeil "all have their name from Noah's son Shem" and are therefore direct descendants of Noachic pure Ur-religion (p. 275). The same is true for the Brachmanes of India who were so closely associated with these Samanaei by St. Jerome (p. 277). Even "our Druids" worshipped "the only true God," believed "in the immortality of the soul" as well as "the resurrection of our bodies," and adored almost all the very God who "at some point in the future will become man through incarnation from a virgin" (pp. 278-79). The correct doctrinal linage of such descendants of Shem is guaranteed by the fact that "after the deluge, Shem brought the original religion of Enos's descendants to renewed blossom [reflorescere fecit]" (p. 280). Boulduc also paid special attention to Enoch, the sixth-generation descendant of Adam who could boast of having lived no less than 308 years in Adam's presence (pp. 148-49). This excellent patriarch, who at age 365 was prematurely removed from the eyes of the living and has been watching events ever since from his perch in the terrestrial or celestial paradise, had left behind "writings, that is, the book of Enoch, which contains nothing false or absurd" (p. 131). Noah had taken special care to "diligently preserve these writings of Enoch, placing them at the time of the deluge on the ark with no less solicitousness than the bones of Father Adam and some other patriarchs" (p. 138). Boulduc did not know where this famous Book of Enoch ended up, but some well-known passages in scripture specified that it conveyed important information about the activities of angels.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, textual criticism began to undermine the very foundation of such tales, namely, the text of the Old Testament and particularly of its first five books (the Pentateuch). These books had always been attributed to Moses and regarded as the world's oldest extant scripture. But in 1651 Thomas HOBBES (1588-1679) wrote in the third part of his Leviathan that the identity of "the original writers of the several Books of Holy Scripture" was not "made evident by any sufficient testimony of other history, which is the only proof of matter of fact" (Hobbes 1651:368). However, Hobbes did not deny that Moses had contributed some writings: "But though Moses did not compile those books entirely, and in the form we have them; yet he wrote all that which he is there said to have written" (p. 369).

A limited hangout is a form of deception, misdirection, or coverup often associated with intelligence agencies involving a release or "mea culpa" type of confession of only part of a set of previously hidden sensitive information, that establishes credibility for the one releasing the information who by the very act of confession appears to be "coming clean" and acting with integrity; but in actuality by withholding key facts is protecting a deeper crime and those who could be exposed if the whole truth came out. In effect, if an array of offenses or misdeeds is suspected, this confession admits to a lesser offense while covering up the greater ones.

A limited hangout typically is a response to lower the pressure felt from inquisitive investigators pursuing clues that threaten to expose everything, and the disclosure is often combined with red herrings or propaganda elements that lead to false trails, distractions, or ideological disinformation; thus allowing covert or criminal elements to continue in their improper activities.

-- Limited Hangout, by Wikipedia

By contrast, Isaac LAPEYRERE (1596-1676) -- who wrote earlier than Hobbes and influenced him though his book on the pre-Adamites appeared later -- was far more radical in questioning whether Moses had in fact written any of the first five books of the Old Testament:

I know not by what author it is found out, that the Pentateuch is Moses his own copy. It is so reported, but not believed by all. These Reasons make one believe, that those Five Books are not the Originals, but copied out by another. Because Moses is there read to have died. For how could Moses write after his death? (La Peyrere 1656:204-5).

La Peyrere's conclusion was shocking:

I need not trouble the reader much further, to prove a thing in itself sufficiently evident, that the five first Books of the Bible were not written by Moses, as is thought. Nor need anyone wonder after this, when he reads many things confus'd and out of order, obscure, deficient, many things omitted and misplaced, when they shall consider with themselves that they are a heap of Copie confusedly taken. (p. 208)

Such textual criticism2 initiated "a chain of analyses that would end up transforming the evaluation of Scripture from a holy to a profane work" (Popkin 1987:73). Until La Peyrere, the Bible had always been regarded as a repository of divine revelation communicated by God (the "founder" figure) to a "transmitter" figure (in this case Moses). Unable to reconcile biblical chronology and events with newly discovered facts such as American "Indians" and Chinese historical records, La Peyrere came to the conclusion that the Bible contained not the history of all humankind but only that of a tiny group (namely, the Jews). His rejection of Moses' authorship, of course, also entailed doubts about the Bible's revelation status: if it was indeed revealed by God, then to whom? To a whole group of people whose notes were cut and pasted together to form a rather incoherent creation Story with "many things confus'd and out of order"? At the end of the chain of events described by Popkin, the Bible was no longer "looked upon as Revelation from God, but as tales and beliefs of the primitive Hebrews, to be compared with the tales and beliefs of other Near Eastern groups" (p. 73), leading Thomas Paine to declare: "Take away from Genesis the belief that Moses was the author, on which only the strange belief that it is the word of God has stood, and there remains nothing of Genesis, but an anonymous book of stories, fables and traditionary or invented absurdities or downright lies" (Paine 1795:4).

Take away from Genesis the belief that Moses was the author, on which only the strange belief that it is the word of God has stood, and there remains nothing of Genesis but an anonymous book of stories, fables, and traditionary or invented absurdities, or of downright lies. The story of Eve and the serpent, and of Noah and his ark, drops to a level with the Arabian tales, without the merit of being entertaining; and the account of men living to eight and nine hundred years becomes as fabulous immortality of the giants of the Mythology.

Besides, the character of Moses, as stated in the Bible, is the most horrid that can be imagined. If those accounts be true, he was the wretch that first began and carried on wars on the score or on the pretence of religion; and under that mask, or that infatuation, committed the most unexampled atrocities that are to be found in the history of any nation, of which I will state only one instance.

When the Jewish army returned from one of their plundering and murdering excursions, the account goes on as follows: Numbers, chap. xxxi., ver. 13:

"And Moses, and Eleazar the priest, and all the princes of the congregation, went forth to meet them without the camp; and Moses was wroth with the officers of the host, with the captains over thousands, and captains over hundreds, which came from the battle; and Moses said unto them, Have ye saved all the women alive? behold, these caused the children of Israel, through the council of Balaam, to commit trespass against the Lord in the matter of Peor, and there was a plague among the congregation of the Lord. Now, therefore, kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman that hath known a man by lying with him; but all the women-children, that have not known a man by lying with him, keep alive for yourselves."

Among the detestable villains that in any period of the world have disgraced the name of man, it is impossible to find a greater than Moses, if this account be true. Here is an order to butcher the boys, to massacre the mothers, and debauch the daughters.

-- The Age of Reason, by Thomas Paine

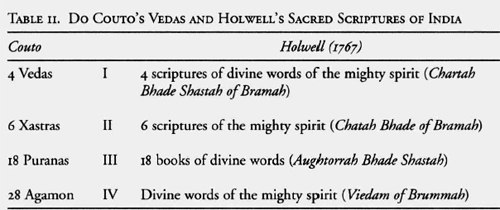

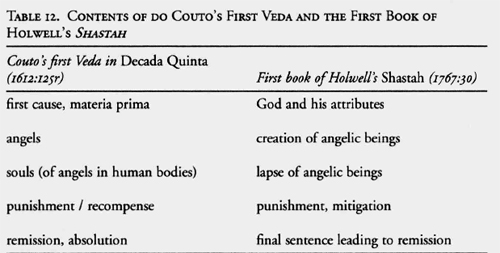

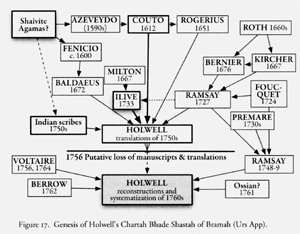

But such loss of biblical authority was a gradual and painful process that frequently elicited the kind of apologetic intervention evoked by Walker in The Ancient Theology. I doubt that Walker would have gone as far as including the Bible among his pseudepigraphic and misdated texts. Yet if one views phenomena like the Reformation from the perspective of Ur-traditions, the biblical text appears as a (misdated) record of "original teaching" used by reformers like Calvin and Luther in their effort to discard "Romish" degenerations and to restore what they took to be the "genuine," "original" religion revealed by the "founder" God to "transmitters" from Adam and the antediluvian "patriarchs" to Noah, Abraham, Moses, and ultimately the authors of the New Testament. But this kind of Reformation was soon denounced as degenerate in its own right, for example, by the radical English deists who regarded "genuine" Christianity not as revealed to any particular Middle Eastern tribe but as engraved in every human heart. From this perspective, Christianity was -- as Matthew TINDAL (1657-1733) in 1730 succinctly put it in the title of his famous bible of the Deists -- exactly "as Old as Creation," and the holy Gospel was no more than "a Republication of the Religion of Nature" (Tindal 1995). While biblical answers became suspect and alternative creation narratives began to be culled from apparently far more ancient sacred texts, the search for humankind's origins, its "original" religion, and its oldest sacred scriptures had to begin again. In this "crisis of European consciousness," a number of men sought to anchor Europe's drifting worldview anew in the bedrock of remotest antiquity via a solid Ur-tradition chain. Among them was an Englishman who defended the Middle Eastern and biblical framework while dreaming of restoring Noah's pure religion (Isaac Newton); a Scotsman who determined that China offered better vestiges of the Ur-religion and wanted to reinterpret the Bible accordingly (Andrew Ramsay); and the Irish protagonist of the next chapter, John Zephaniah Holwell, who presented Europe with an Indian Old Testament that -- he alleged -- was so much older and better than Moses's patchwork that it could form the basis for the ultimate reformation of Christianity.

Newton's Noachide Religion

Isaac NEWTON (1642-1727) is, of course, known as one of the greatest scientists of all time, but his theological and chronological writings have become the focus of increasing attention. They amount to more than half a million words and are in great part still unpublished; but their study4 points to a central "Ur-tradition" pattern in Newton's worldview. For example, modern specialists point out that "it can be shown how Newton regarded his natural philosophy as an integral part of a radical and comprehensive recovery of the true ancient religion, which had been revealed directly to man by God" (Gouk 1988:120); that Newton tried to prove "that his scientific work in the Principia was a rediscovery of the mystical philosophy which had passed to the Egyptians and the Greeks from the Jews" (Rattansi 1988:198); and that the great scientist "believed that alchemical writings preserved a secret knowledge which had been revealed by God" (Golinski 1988:158). Newton apparently saw himself as a regenerator of an Ur-wisdom that had been encoded in symbols and transmitted through dark and degenerate ages by a line of eminent men (patriarchs). The italicized words in this sentence are all elements of what I call Ur-traditions.

Newton developed such views over many decades but dared to discuss them only with a few close friends. But the last sentences of his famous Opticks let the reader catch a glimpse:

If natural Philosophy in all its Parts, by pursuing this Method, shall at length be perfected, the Bounds of Moral Philosophy will be also enlarged. For so far as we can know by natural Philosophy what is the first Cause, what Power he has over us, and what Benefits we receive from him, so far our Duty towards him, as well as that towards one another, will appear to us by the Light of Nature. And no doubt, if the Worship of false Gods had not blinded the Heathen, their moral Philosophy would have gone farther than to the four Cardinal Virtues; and instead of teaching the Transmigration of Souls, and to worship the Sun and Moon, and dead Heroes, they would have taught us to worship our true Author and Benefactor, as their Ancestors did under the Government of Noah and his Sons before they corrupted themselves. (Newton 1730:381-82).

This closing passage suggests that for Newton the religion of the "golden age" or Ur-religion was preserved by Noah and his sons who were thoroughly monotheistic. Far from being only the religion of the Hebrews, this Ur-religion reigned for a long time everywhere, even in Egypt (Westfall 1982:27). But these "blinded heathen" who had initially shared Noah's Ur-religion could barely remember the cardinal virtues because their religion at some point degenerated into the worship of false gods, objects of nature, and dead heroes and into the teaching of the transmigration of souls.

Newton had closely studied Thomas Burnet's Archaeologiae philosophicae of 1692 (see Chapter 3), and though the outlines of his historico-theological system were already developed in 1692, Burnet's influence is unmistakable:

Like Burnet, Newton regarded Noah, rather than Abraham or Moses, as the original source of the true religion and learning; consequently, he, too, argued that vestiges of truth could be found among the ancient Gentile peoples as well as that of the Jews since all were descendants of Noah and his sons. Both also shared the belief that modern philosophy was contributing to the recovery of ancient truths which had been distorted after Noah's death. (Gascoigne 1991:185)

Newton clearly thought that an initial divine revelation was the ultimate source of all religion, that this Ur-religion was once shared by all ancient peoples. Nevertheless, he sought to root his views firmly in the Old Testament narrative. Monogenesis and the universality of the great flood, for example, were nonnegotiable. Thus, all postdiluvial humans, gentiles and Hebrews alike, originally shared the religion transmitted by Noah and his sons, and vestiges of this religion could be found in all ancient cultures. Newton explained:

From all of which it is manifest that a certain general tradition was conserved for a very long time among the Peoples about those things which were passed down most distinctly from Noah and the first men to Abraham and from Abraham to Moses. And hence we can also hope that a history of the times which followed immediately after the flood can be deduced with some degree of truth from the traditions of Peoples. (Yahuda Ms. 16.2, f. 48; Westfall 1982:22-23)

But Newton did not go as far as taking Chinese chronology into account. He owned and studied Philippe Coupler's 1687 work that was discussed in the previous chapter yet grew convinced that the famous burning of books by Emperor Shih Huangdi in the third century B.C.E had reduced all ancient Chinese history to legend. In the New College Manuscript (I, fol. 80v) Newton wrote,

And there are now no histories in China but what were written above 72 years of this conflagration. And therefore the Story that Huan ti founded the monarchy of China 2697 years before Christ is a fable invented to make that Monarchy look ancient. The way of writing used by the Chinese was not fully invented before the days of Confucius the Chinese philosopher & he was born but 551 years before Christ & flourished only in one of the six old kingdoms into which China was then divided. (Manuel 1963:270)

Newton instead studied Middle Eastern chronologies and used them to defend the Bible as the most reliable source for remote antiquity. Moses had in his opinion originally written a history of creation, a book of the generations of Adam, and the book of the law. Though these oldest books "have long since been lost except what has been transcribed out of them in the Pentateuch now extant" and though the existing text of the Pentateuch was in his opinion redacted by Samuel rather than Moses (Manuel 1963:61), Newton remained firmly convinced that the first books of the Old Testament "are by far the oldest records now extant," that the Bible is the most authentic history of the world, and that the Kingdom of Israel was the first large-scale political society with all the attributes of civilization (p. 89).5 Manetho of Heliopolis, Berosus the Chaldaean, and others had, like the Persian and Chinese historians, created extravagant chronologies that were infinitely less reliable and old. In a chapter of his Chronology dedicated to the Persian Empire, Newton wrote,

We need not then wonder, that the Egyptians have made the kings in the first dynasty of their monarchy, that which was seated at Thebes in the days of David, Solomon, and Rehoboam, so very ancient and so long-lived; since the Persians have done the like to their kings Adar and Hazael, who reigned an hundred years after the death of Solomon, "worshipping them as gods, and boasting of their antiquity, and not knowing," saith Josephus, "that they were but modern." (Newton 1785:5.263)

Newton employed such chronologies that "magnified their antiquities so exceedingly" (p. 263) in a manner that much resembled that of William Jones a century later, namely, to confirm the biblical account and vindicate biblical authority; but Jones was to use the even more hyperbolical Indian chronologies. Newton's final system appeared, as Frank Manuel put it, "as a eulogy of Israel" and is evidence "for his central proposition that the Hebrews were the most ancient civilized people" (Manuel 1963:97). Though the Bible bestows greater antiquity on the Egyptian and Assyrian royal institutions than on the tribes of Israel, Newton "was able to cling to his idee fixe throughout the revision of the history of antiquity, both in the fragments and in the final Chronology" (p. 99).

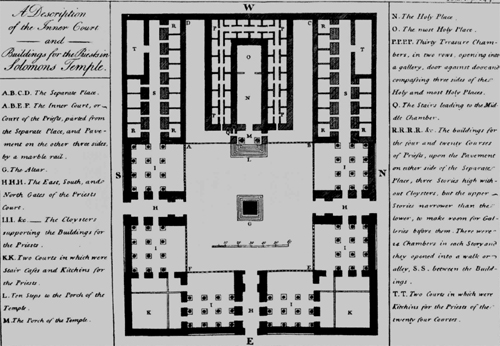

Newton's "ancient theology" was thus -- unlike that of Ramsay and Holwell -- still exclusively rooted in the Middle East and the Bible. Since events before the biblical deluge remained hazy due to the fragmentary character of the Pentateuch and the lack of reliable ancient pagan sources, Newton's history of religions really starts with Noah and his sons. His true religion "most closely resembled that which prevailed at the time of Noah, immediately after the Deluge, before the idolatry -- which to Newton was the root of all evil not only in religion but also in politics and even philosophy -- began to corrupt it" (Gascoigne 1991:185). The symbol of this pure original religion is the Temple of Solomon (Figure 12), which not only features the eternal flame on a sacrificial altar at the center but also a geometrically precise representation of the heliocentric solar system.

Newton's "prytanea," sacred cultic places around a perpetual fire, symbolize God's original revelation and are at the source of the transmission line.6 Cults with prytanea were for Newton the most ancient of all cults. According to him this religion with the sacred fire "seems to have been as well the most universal as ye most ancient of all religions & to have spread into all nations before other religions took place. There are many instances of nations receiving other religions after this but none (that I know) of any nation's receiving this after any other. Nor did ever any other religion which sprang up later become so general as this" (Westfall 1982:24).

This religion around the prytanea was professed by Noah and his sons.

Figure 12. Newton's map of Solomon's temple (Newton 1785:5.244).

They spread "the true religion till ye nations corrupted it" (p. 25). This first corruption consisted in forgetting that the symbols in the prytanea (for example, lamps symbolizing heavenly bodies around the central "solar" flame) are symbols, leading men to engage in sidereal worship. It is of interest to note that Newton's history of religion -- and, I might add, Ur-traditions in general -- are intimately linked to the encoding and decoding of symbols. Here the degeneration process begins with a misunderstanding of symbols [!!!]; and this misunderstanding eventually leads to the worship of dead men and statues, the belief in the transmigration of souls, polytheism, the worship of animals, and other "Egyptian" inventions. In parallel with such religious degeneration, the false geocentric system took hold thanks to a late Egyptian, Ptolemy (pp. 25-26).

The first major postdiluvial regeneration was due to Moses who, according to Newton, "restored for a time the original true religion that was the common heritage of all mankind" (p. 26). But soon enough the degeneration process began anew, punctuated by calls of prophets for renewal, until Jesus came not to bring a new religion but rather to "restore the original true one" not solely for the Jews but for all mankind (p. 27). Soon enough, another round of degeneration set in with the Egyptian Athanasius, the doctrine of the Trinity, and Roman Catholic idolatry, which got worse and worse until the Reformation cleaned up some of the mess. But Protestantism and Anglicanism were not immune from corruption either, which is why Newton (who was adamantly opposed to the Trinity) felt the need to call -- in a very muted voice and in heaps of unpublished notes and manuscripts -- for one more restoration of true, pure, Noachic religion and wisdom.