by admin » Sun Oct 31, 2021 4:08 am

by admin » Sun Oct 31, 2021 4:08 am

TRANSLATION OF THE EXTRACTS [FOLIOS 91 (b) TO 105 (b)] FROM SIRAT-I-FIROZSHAHI.

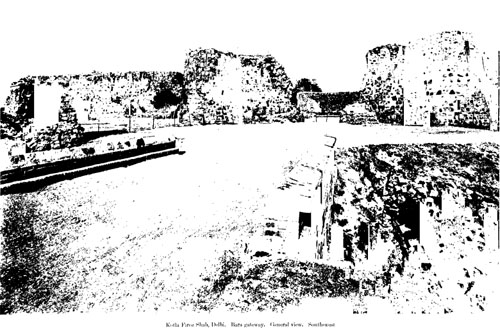

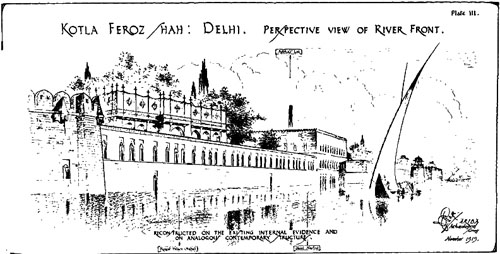

A Persian manuscript in Nastaliq character dated 1002 A.H. in the Oriental Public Library, Bankipore, Patna. The extracts deal with the removal of the so-called Minarah-i-Zarrin (golden pillar) — the monolith containing the edicts of Asoka from the village of Topra near Khizrabad to Firozabad now known as Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi.

The Golden Pillar.

[91-b] Verse —

1. This pillar, high as the heaven, is made of a single block of stone and tapers upward, being broad at the base and narrow at the top.

2. Seen from a hundred farsang1 [A farsang varies from 2-1/2 to 8 miles.] it looks like a hillock of gold, as the Sun when it spreads its rays in the morning.

3. No bird— neither eagle, nor crane— can fly as high as its top; and arrows, whether Khadang or Khatai2, [Khadang-poplar, hence arrows made of indigenous poplar. Khatai-arrows imported from Khata. Distances were sometimes counted in arrowshots m those days.] cannot reach to its middle.

4. If thunder were to rage about the top of this pillar, no one could hear the sound owing to the great distance (between the top of the pillar and the ground).

5. O God! how did they lift this heavy mountain (i.e., the pillar)?; and in what did they fix it (so firmly) that it does not move from its place?

6. How did they carry it to the top of the building which almost touches the heavens and place it there (in its upright position)?

7. How could they paint it all over with gold, (so beautifully) that it appears to the people like the golden morning!

8. Is it the lote-tree of paradise (tuba) which the angels may have planted in this world or is it the heavenly "sidrah"3 [The (imaginary) plum tree m the 7th Heaven, marking the limit beyond which no human or celestial being's have any knowledge of anything (Mantahal Arab ).] which the people imagine to be a mountain?

9. Its foundations have been filled with iron and stone; and its trunk and branches (i.e., shaft and capital) are made of gold and corals.4 [In the original MS the first word ([x]) of the last hemistich is superfluous. The words [x] at the beginning of the next prose line ought to come at the end of the verse. These verses are, if not the earliest, one of the earliest examples of Musamma' verse so popular in later days.]

And truly as the removal of the stone monolith and its erection in front of the mosque by the order of the King is a wonderful achievement, the methods employed in its removal and erection are being recorded in this book, in order that the description may be useful for those who wish to know the details thereof. This work was done at the time when [92-a] by the grace of the Almighty God, the King (whose kingdom may ever endure) was able to conquer the country of Sind — and this country is so very difficult to control and administer that people generally believe the task to be impossible and the continuance of disturbance there for generation after generation have affected the kingdom like a chronic disease, as is well known to the public: yet the King with the help of his grand cavalry5 [Gardun or some other word has obviously been left out between [x] and [x].] and star-like army marching under the victorious banners shining as the bright Sun, may God ever keep them victorious, totally subdued that province, and (was able to) bring the chiefs, headmen and zamindars of that province together with their wives, children and near relations to the capital -- as has already been mentioned in this book in the chapter dealing with the King's wars and heroic deeds —; and when the victorious banners returned to Firozabad, the capital (may it remain safe until the end of the world), it so happened that the King resolved to go out hunting towards the Sirmur hills. On a former hunting expedition too the King had visited the neighbourhood of these hills and had seen the stone pillar in the village Topra1 [Alias Maqbulabad, as related on folio 92-b.] on the bank of the Janan (Jamna?) which flows into (i.e., supplies water to) the Firoz-bah canal.

On the pillar is an inscription, the characters of which are unintelligible to the men of this period; but the (native) historians have a tradition to the effect that four thousand odd years have passed since this pillar and a temple were erected at this place. Another inscription on the pillar is only 249 years old and is said to mention that Bisal Deva, Chohan, Rai of Sambhal, who came to worship certain idols on the banks of the Saraswati river, found this pillar in its present position. It is also said that Doa (or Dowa) the Mongol king and Qatlugh Khwaja, the Mongol, visited this place with their armies; and that later on Tirmeshirin2 [Tirmeshirin, ruler of Bukhara and Mawaraun Nahr, was the son of ([c]) Dowa, and brother of Katlugh Khudja, of the family of Chingiz Khan. Tirmeshirin invaded India in 728 H. (1328-29 A.D.), and carried his arms to within sight of Delhi the ruler whereof, Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq, was absent in the Deccan at that time. (Badayuni, Persian Text, p. 227-28).] also visited the place and [92-b] attempted to split the pillar by burning a huge fire around its base, but the pillar did not crack -- though some effect of the fire may still be traced. The firewood required for the purpose was got together by ordering that each man of his army who rode an animal was to bring a load of firewood twice.

The King of Islam now prayed to the Almighty God that he may be enabled to remove the stone pillar and re-erect it near the Jum'ah mosque of Firozabad on the bank of the Javan (Jamna). With this purpose the King went on a (second) hunting expedition to the Sirmur hills, and in the village of Maqbulabad, alias Topra, which is situated on the banks of the Jatan (Chitang?)3 ['Afif in his Tarikh-i-Firoz Shahi, p. 310 gives the name of the river as Jamna. But the text reads more like Chanab. It might be Chitang. But it should probably be Jamna.] the stream which feeds the Firoz-bah canal stood the stone pillar, the like of which in height and circumference had not been seen by any one.

(Verse) None ever saw such a beautiful pillar under the canopy of the heavens which is unsupported by any poles.

The King saw this pillar (for the second time).

The sages and wise men of the time were simply astonished at the sight, and though they dived deep into the sea of thought they succeeded not in bringing out the pearl of the solution of these secrets -- namely whence and how this heavy and lofty stone monolith was brought to this place and what were the exact engineering methods employed in its erection here. Verily such an achievement could hardly have been accomplished by human beings for the simple reason that it is beyond the powers of Man. Some of the learned infidels on the authority of their Hindi books, said that the pillar had grown out of the (bowels of the) earth and reached the heavens4, [Afif (p. 305) mentions that the Hindus believed the pillar to have been used as a stick (lathi) by Bhim, the hero of the Mahabharata. Almost every big column of ancient days in India is called the lathi of Bhim or Bhimsen.] while others said that underneath the pillar was a magical talisman and that nobody could remove the pillar, and that if excavations were made around the base of the pillar large vipers, snakes, scorpions and wasps would come out and bring the people to grief. [93-a] Such were the things which the King heard: (but) as he was determined to remove the pillar he said "By the grace of the Creator, who sees and hears everything, we shall remove this lofty pillar and make a minar of it in the Jum'ah Mosque of Fnozabud where, God willing, it shall stand as long as the world endures.” So the King ordered the engineers and all the wise, shrewd, and ingenious men of the time to devise each man according to his own intelligence, understanding and ingenuity, the means of taking down the pillar, its removal to Firozabad, which is the resort of all the occupants of the inhabited quarter1, [i.e., the earth as distinguished from the water which covers the remaining three quarters of our Earth.] and its re-erection in the Jum’ah Mosque of Firozabad, and to let the King know of the various methods they would suggest. But in truth, those who for their shrewdness, sagacity and ingenuity claimed to be the equals of Avicenna, Plato, Galenus, Aristotle and Buzurj-mihr2, [Name of the prime minister of Nushirawan, the famous Sassani King of Persia.] caught the skirts of inability with the teeth of excuses in this task, and considered that the removal of the pillar was absolutely impossible. Thereupon His Majesty the King of Islam who has been adorned and amply endowed by God with all religious and worldly virtues and with sound knowledge and perfect wisdom, himself devised ingenious plans and methods of each operation connected with this achievement. The felling and transporting of the pillar was accomplished with the help of divine inspiration, in accordance with human understanding as revealed in the king's wise plans in the month of Muharram 760 A.H. (September 1367 A.C.). And every detail of the work including the tying of ropes and construction of masonry piers: pulling the ropes in all directions and balancing the pillar with their help: the employment of elephants for dragging the (fallen) pillar, and following on their failure [93-b] the employment of longer ropes with 20,000 men and their success in carrying the pillar to the banks of the Jamna; then arranging well-balanced boats for the pillar, loading the pillar on the boats and floating the same: its journey to Firozabad: the making of all the arrangements over again for removing the pillar and carrying it in front of the Jum’ah Mosque, there constructing a (large) building, raising and placing the pillar thereon with the help of pulleys, etc., and re-erecting the pillar according to the laws of wisdom — a gift of the most exalted God, all this was done exactly in the same way as was ordered by His Majesty the King, may God perpetuate his rule and sovereignty.

The plan of taking down the pillar to the ground was suggested by the King (as follows): —

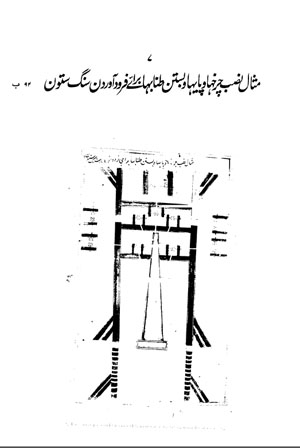

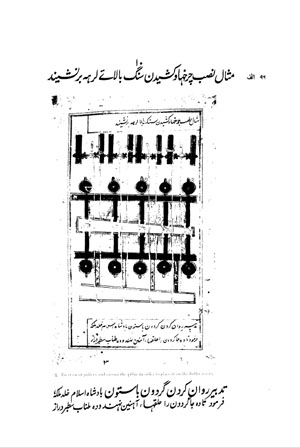

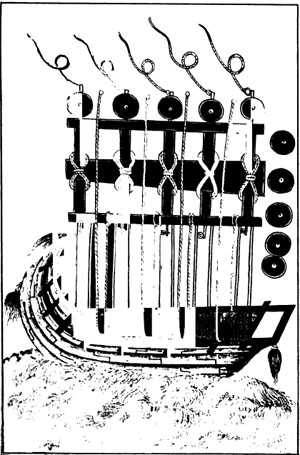

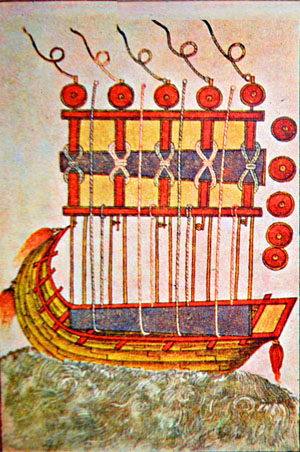

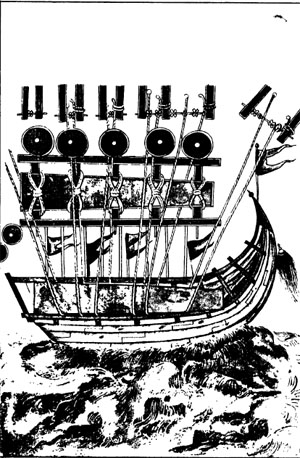

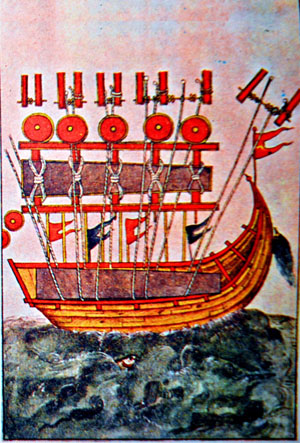

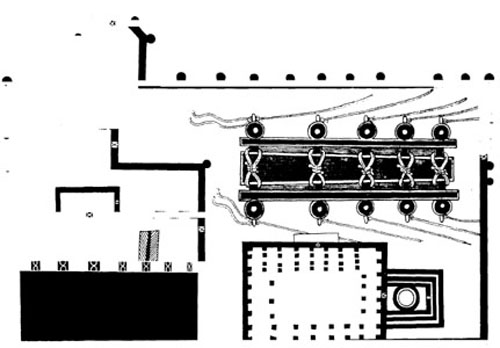

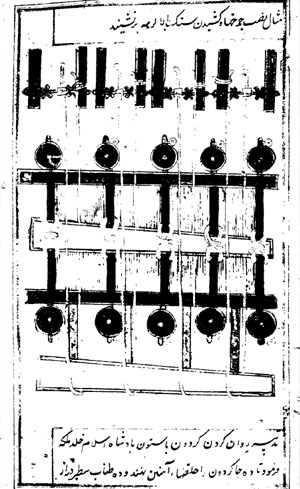

Construct six wooden piers like unto the piers of a dome, each ten yards in circumference and of the same height as the monolith itself. Two of these piers should be constructed behind the pillar and two (to the right and two)3 [The manuscript does not contain these words; but in order to make up the 6 piers spoken of in the previous line I have added these words in the translation.[] on the left. The distances of the piers should be six yards from each other and seven yards from the monolith. The piers then should be strengthened with iron nails and wrapped with raw hides and ropes, each pier being further supported on three sides by two very thick and long wooden (slanting) supports on each side. The wooden piers should then be joined to each other by means of (two) large wooden beams in the middle and at the top, and on each of the beams a wheel4 [The illustration it will be seen, does not tally with the description in the manuscript; two of the beams have 2 pulleys each.] should be fixed in a vertical position whereon the ropes could easily pass. Such wheels should be fixed at five places, two on either side of the monolith and one at the back. Then in order to hold and move (i.e., to tighten or relax) these ropes, five pulleys (or winches?) should be set up (on three sides of the pillar, i.e., two at either side and one at the back), and behind the pulley at the back (of the monolith) should be the end pier (aqban) and another wheel should be fixed there with the necessary rope tied to it. The ends of these six ropes5 [Only five of the ropes are shown in the illustration.] should be tightly bound round the pillar so that its upper portion [94-a] may be firmly held by them. And to the two piers in front of the pillar should be tied thick strong ropes, running from end to end, in twenty places so that there shall be a rope at every yard6. [The illustration shows only ten of these ropes.] So that when the top of the pillar is lowered, it shall rest on the ropes. And four long ropes should be tied to the top of the pillar. These ropes may be pulled towards the front when it is desired to incline the pillar from its upright position and at the same time the ropes at the pulleys may be relaxed yard by yard until the pillar rests on the horizontal ropes tied in front. Then the particular rope on which the top of the pillar rests may be slowly relaxed and untied: the pillar pulled towards the front and the ropes at the pulleys relaxed bit by bit and the operation repeated until the head of the pillar shall rest on the pasheb in front. [This pasheb should he constructed at a distance of six yards from the base of the pillar; it should be fifteen yards in length ten yards in width, and sixteen yards high, but the height should (decrease gradually to form a slope until it is) only five yards on the side facing the pillar. This pasheb should be made of mud, and on all four sides it should be strengthened with wooden supports.1 [The passage in square brackets is deleted by the scribe. The way of doing this is interesting. At the beginning of the passage he has written [illegible], 'omit' or 'delete' and at the end [illegible], i.e., 'up to this point'. The passage is given in its proper position on folio 95-(a).]]

[94-b] Illustration showing the erection of the piers and pulleys and the tying of ropes for taking down the stone pillar. (Illustration Fig. 1)

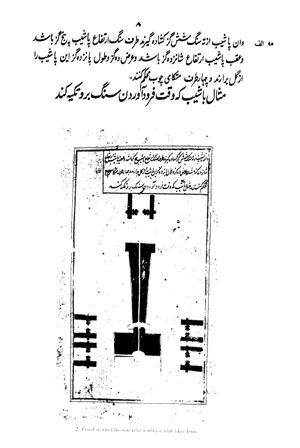

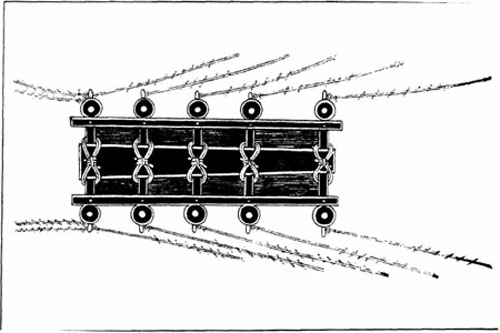

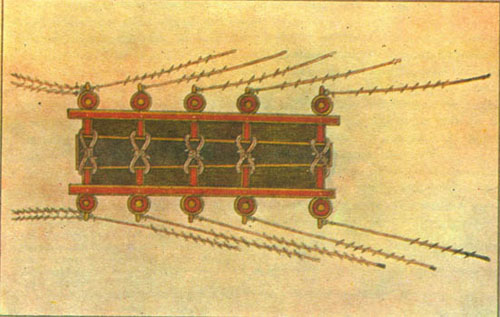

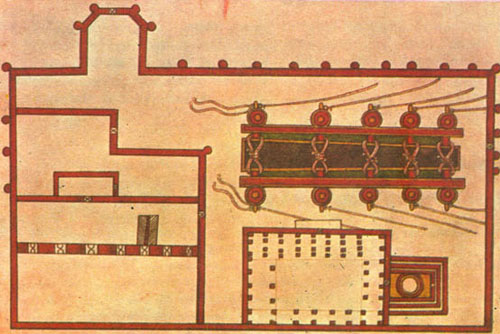

[95-a] And this pasheb should be constructed at a distance of six yards from the base of the pillar: it should be fifteen yards wide, ten yards deep and sixteen yards high but the height should decrease gradually to form a slope until it is only five yards on the side facing (i.e., nearest) the pillar. This pasheb should be made of mud and on all four sides it should be strengthened with wooden supports.

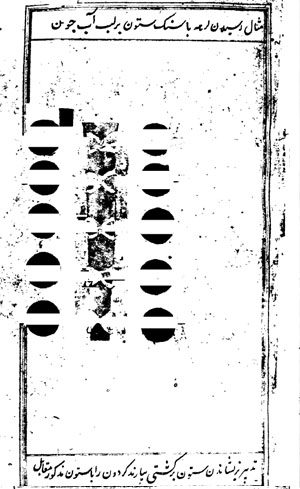

Illustration showing the pasheb on which the stone pillar should rest while it is being taken down. (Illustration Fig. 2).

[95-b] And the stone (pillar), before it is taken down, should be covered all round with long reeds and wrapped with raw hides: and large quantities of paddy straw should be placed over the pasheb so that the stone may not receive any hurt or injury. And when the pillar rests on the pasheb, mud to the depth of about a yard may be removed from under the pillar, keeping all the ropes at the back and sides quite taut. When one yard of mud is removed, the ropes at the back pulleys may be (slowly) relaxed. This should be repeated again and again until the pillar lies prone on the ground.

The Royal order was followed and accordingly the pillar laid its head low on the ground.

The device of placing the pillar on the flat cart (gardun) known as ladha in the Hindi language. —

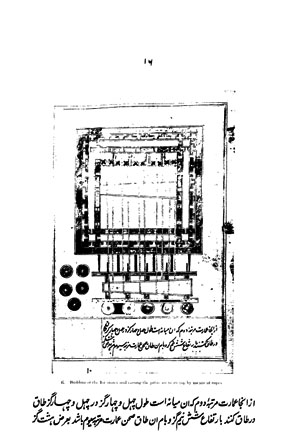

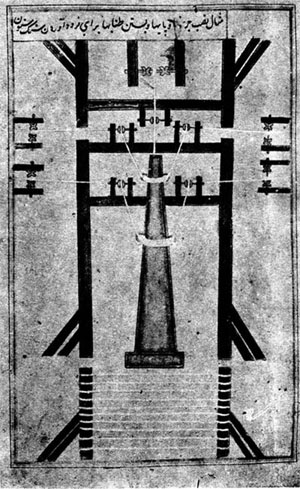

The King of Islam, whose rule be perpetuated, ordered the preparation of a cart equal in length to the length of the stone pillar and provided with ten2 [Afif (p. 309) says that the gardun had 42 wheels, but that is evidently incorrect.] wheels, each ten yards in circumference. The cart should then be placed length-wise near the pillar and on the side nearest the pillar, the wheels of the cart should be pulled off and their axle-rods supported on a pakka brick wall constructed at a distance of xix yards from the pillar. A pasheb should then be constructed from the top surface of this wall to the base of the pillar, and on the other side of the cart where the wheels are still on their axles should be created (a row of) four pulleys at a distance of ten yards3 [A yard was equivalent to about two feet.] from the cart. The ropes of the pulleys should then be tied to the pillar at four points; four other ropes may also be tied (to the pillar) in between4 [The word in the manuscript is [x] as I have translated.] (sic) and pulled with the hands5. [The extra four ropes do not appear to be shown in the illustration.] Then let the pulleys revolve as much as is desirable and (when the pillar has been raised and is to be lowered down on the cart then) yield the ropes slowly until the pillar is correctly placed and balanced on the cart. Then the (pakka) wall may be removed from under the axle-rods, the wheels re-attached to the cart, and earth etc., cleared from below the same, so that it may be ready to start. The Royal orders were acted upon and the result was exactly as it was expected.

[96-a] Illustration showing the erection of pulleys and the raising of the pillar in order to place it on the ladha. (Illustration Fig. 3).

The device of carrying the pillar on the gardun or ladha. —

The King ordered that ten large iron rings should be attached to either side of the cart. (96-b). Thick long ropes may then be tied to the rings at one end and to the necks of elephants at the other. Similarly three thick ropes may be tied to the front of the cart and passed on to the necks of bullocks: so that the cart may thus be dragged forward from three sides, by bullocks in front and by elephants on the right and left. Four ropes may also be tied at the back of the cart and a party of men should hold them, pulling the ropes backward where the ground may slope thus preventing the cart from going down by force and out of control as that would not be free from danger: and where the ground in front of the cart may rise the party holding the back ropes should also help in dragging the cart forward. So in truth it was done: but the mountain-like elephants, lofty and furious, though they tried to drag it with all their prowess, did not succeed in their efforts and could not move the cart: so the King ordered the elephants to be removed and the pillar to be dragged by men both slaves and free men. Great Khans and well-known persons, courtiers, well-to-do gentlemen and ordinary men all caught hold of the ropes only too willingly (lit. passed the ropes over their obedient necks) to drag the cart forward. The cart began to move and all were pleased beyond measure, and in token of this practical demonstration of their loyalty, exclaimed.

(Verse).

The load which could not be carried by a thousand of your furious elephants, we carry it with ease on our own necks.

And thus, with all desirable order and systematic arrangements, the pillar was taken to the bank of the Jamna where a boat was ready. God be praised and thanked.

[97-a] Illustration showing the arrival of the ladha with the stone pillar, at the bank of the Jamna river. (Illustration Fig. 4).

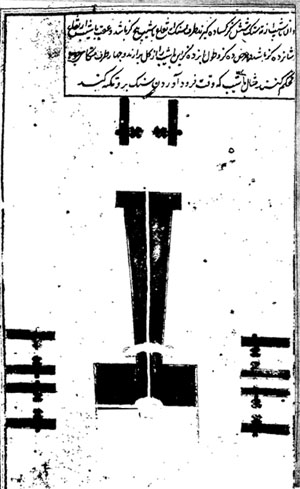

The device of plating the pillar on the boat. —

(The King ordered that) the cart carrying the pillar should be brought to [97-b] the ghat where the boat was to be moored. At the place where the boat shall be tied, the ground should be dug as much as necessary1, [To permit of the boat being brought close to the river bank.] so that it may be all right.2 [The manuscript does not give the verb after [x].] The wheels towards the boat side may then be removed from the cart so that on this side the cart (axles) should rest on the ground. Four pulleys should then be erected in a line (lit. facing each other) behind the pillar at a distance of ten yards and two pulleys at each end of the pillar at the same distance. To these pulleys strong ropes should be tied and a pasheb of thick wooden beams constructed from the pillar right down to the middle of the boat where the pillar will rest. Then the ropes of the four pulleys opposite the pillar as well as the four ropes (of the corner pulleys?) which would be held by men, should be relaxed yard by yard but all the time held firmly so as to move one end of the pillar exactly as much as the other. In this way it should be moved until the pillar rests exactly in the middle of the boat.

In the boat itself each alternate opening [should be filled in with lime-mortar, the other being left for draining water. Further, a large frame (tarashould be prepared with ten long beams of sembal and tar trees and suspended along either side of the boat. These frames will be helpful in loading and floating the boat. Andn) on the other, i.e., river-side of the boat, should be bound two huge boats to serve as a support.3 [At the time of loading, the main boat will naturally incline to one side. These extra boats will not allow it to overturn or incline too much.] When the pillar is correctly placed in the boat it should be tied with ropes in eight places to the boat and to the taran. Then all should say Bismillah-i-majecha wa mursaha, i.e., in the name of God may the boat go and anchor4, [Quranic verse recited by Muhammadans when a boat first begins to move because Noab recited it for his Ark.] and the boatmen should begin to row.

Illustration showing the pulling off of the wheels of the cart from one side and the tying of ropes and pulling (up) of the pillar so that it may be placed in the boat.

[98-a]

(Illustration Plate VI, a).

[98-b] until the raft arrives near the fort of Firozabad at the ghat where we1 [ i.e., the King.] have ordered the deepening of the bank of the Jamna.

Illustration showing the arrival of the boat and pillar by the bank of the Jamna, the bringing of a cart near the boat, and the tying of ropes to the pillar in order to remove it from the boat, and place it on the cart.

(Illustration Plate VI, b).

[99-a] From the boat (the King ordered that), the pillar should be removed and carried to the mosque of Firozabad, just in the same way as it was carried on the cart before and shifted from the cart on to the boat;

Illustration showing the departure of the cart with the monolith for the town of Firozabad.

(Illustration Plate VI. c).

[99-b] Illustration showing the arrival of the cart with the pillar, in front of the mosque of Firozabad.

(Illustration Plate VI, d).

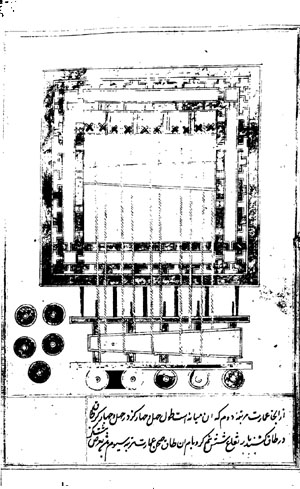

[100-a] Illustration showing the construction of the foundations of a structure. 61 yards square (on which to raise the pillar).

(Illustration Fig. 5).

[100-b] so that by the grace of God Almighty the pillar may be erected in the mosque; and whatever the King had wished or intended God was gracious enough to grant.

The method of erecting the pillar and making it a minar in the Jam'ah Mosque of Firozabad.

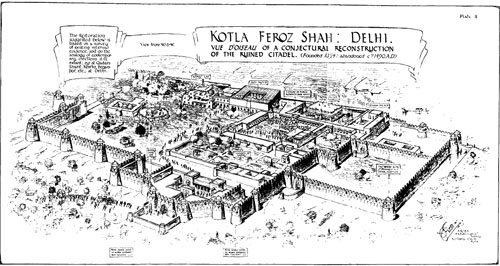

The King of Islam ordered that a large pit sixty one yards square be dug to a depth of seven yards, and the whole of it filled in with stone and mortar (masonry), until the masonry is level with the ground surface, where it should measure only 60 yards square. To these dimensions it (the plinth) should be raised to a height of three yards of which the lower one yard may be left out of consideration2 [And covered with earth (?)] and the top of the remaining two yards considered as the floor of a series of arched chambers. Thus the walls of the chambers shall commence at a height of three yards (from the ground surface) and raised to a height of six yards and a half, the roof being eight yards wide and serving as the floor of the second storey.

Illustration showing the building of the 1st storey and the raising of the pillar on the top of this storey by means of ropes.3 [Folio 100-b ends here, leaving a space of some three inches blank. The illustration occupies folio 101 (a).]

[101-a]

(Illustration Fig. 6).

Above this should be constructed on (intersecting?)4 [taq dar taq [x].] arches, the second or middle storey, forty-four yards square, six yards and a half in height with its roof eight yards wide and forming the floor of the third storey.

[101-b] Illustration showing the (plan of the) second storey.

(Illustration Fig. 7).

[102 -a] And the third storey of this building should be 28 yards square in plan. Of this, a space of nine yards in width on all four sides should be covered by eight domes1, [Three domes on each side.] leaving a space of ten yards square in the centre where the pillar shall have to be erected. On this central space should be constructed, very carefully, a pakka masonry platform with stone and mortar. The third storey should also be six yards and a half in height, the total height of all the three storeys together being 22 yards and a half2. [i.e., inclusive of the plinth which was three yards high.]

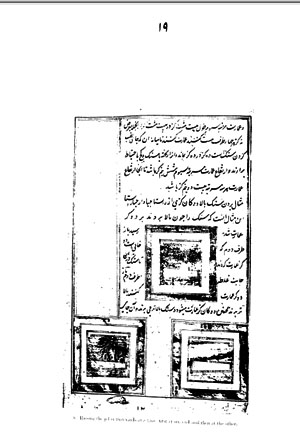

Illustration showing the raising of the pillar two yards at a time, first at one end and then at the other (lit. from right to left and from left to right). (Illustration Fig. 8.)

This illustration shows how the pillar was carried up (to the top of the building). After the masonry was raised to a height of two yards on one side, it would be commenced at the other side, and raised to the same level as the first side so that the pillar may be rolled over to that side. Then again the masonry (and the pillar) would be raised to a further height of two yards on this side and the process would be repeated on the other side, the masonry being raised two yards at a time and the pillar raised accordingly (and placed on the finished masonry whence it would be rolled over to the other side after the intervening gap was filled).

And the central space (in the 3rd storey)3 [Two illustrations follow here. A third is given about the centre of the page.] [102-b] which is ten yards square and where the pillar shall be erected, should be carefully measured and marked so that the distance between the pillar and the domes should be exactly4 [Hasht-gan ([x]) is clearly written in the manuscript, but it is no doubt a mistake, for the actual distance between the domed space and the pillar could not be more than 4 yards each way. [Hasht means eight in Persian]] eight yards on each side. Of the total twenty-two yards length of the pillar, the lower two yards should be fixed into the central masonry platform and the remaining twenty yards be visible. Thus the building being twenty-one yards and a half in height5 [The height of the building should be 22-1/2 yards as given before. The total height is correct.] and the visible portion of the pillar twenty yards, the total height would become forty-two yards and a half (when the pillar is erected). On the top of the monolith should then be set up a capital made of coloured stones and consisting of a pedestal (kursi) a myrobalam-shaped ornament (halilah), a globe (minjuq) and a crescent (mah). The height of this capital should be seven yards and a half so that the total height (of the top of the pillar from the ground) may be full fifty yards. (Moreover), at the top of the third storey, at the four corners, should be placed the figures of four lions, each four yards square in plan and five yards in height.

Illustration showing the third storey. (Illustration Fig. 9.) [103-a] Description of the methods of constructing the building and raising the stone pillar.

By the command and suggestion of the King of Islam it was ordered that the following method be employed for raising the pillar: —

First, a sloping pasheb, twenty-eight yards wide, be constructed from the ground up to the roof of the first storey which is nine and a half yards in height. Eight pulleys should then be set up on this roof and two at the corners. The two ends of the pillar should be tied to the corner pulleys; and ten more ropes should be tied to the pillar and held by men. Then twenty poles of wood, called sang by the Kahars in India, should be placed at intervals across the pasheb, and two thick wooden beams equal in length to that of the pillar itself, and each five yards in circumference should be placed along the pillar, one on either side. Now let the pulleys be turned and the hand-ropes drawn. As the pillar is pulled upward, the two thick supporting beams shall move along with it. When the pillar has been taken over the pasheb to the level roof of the first storey, it should be rolled close to the pulleys and kept there. Then on this side, where the pillar is placed and the pulleys stand, a space of about the circumference of the pillar be left out at either end and the rest of the building raised to a height of two yards. Now the stone pillar should again be raised with the help of ropes and placed on the top of the newly raised walls. (When the gap has been filled in), the pillar may again be rolled over to that side and leaving out a space of about the circumference of the pillar the rest of the structure raised to a height of two yards exactly in the same way as before. In this manner the pillar may be raised two yards at a time until it reaches the top of the building of which the total height would be twenty-one yards and a half. Then the whole of the top surface (of the third storey) should be levelled up, the central space, where the pillar is to be set up, with stone and mortar and the surrounding portion1 [Literally the words [x] in the manuscript mean "borrowed structure", i.e., one which is only for show. The arched chambers around the central solid space served no structural purpose.] with stone-[103-b]in-mud.

Then the pedestal on which the pillar will stand should be firmly fixed in the centre of the platform with such precision and accuracy that it may be perfectly level, without the slightest inclination to any side. Three stone beams each measuring seven yards in length, one yard in height and one yard deep should then be fixed on the south, east and west of the pedestal.2 [One on each side and close against the pedestal stone.] Over the stone beam fixed on the south side of the pedestal should then be placed another stone beam seven yards in length and one yard high: and over the eastern and western beams, two blocks of stone each measuring two yards in length and one yard in height. Then on the north side should be placed (not fixed) two beams, one, seven yards in length above the other, which should be one yard broad.3 [And of course one yard high and seven yards long like the lower one on the south.] These two beams should be kept ready (but not fixed) until the pillar is erected in its proper position.

The stone pillar should now be placed on a cart with small and revolving wheels and moved to one side until the base of the pillar is in line with the top.4 [i.e., the central line of the whole pillar should be straight line with the central line of the gap left of the north side of the pedestal.]

After this, 24 pulleys should be set up in this way:--

On the south side namely towards the mosque, 8 pulleys.

On the east, i.e., to right of the stone pillar, 6 pulleys.

On the west, i.e. to left of the stone pillar, 6 pulleys.

At the east and west angles5 [N.N.E. and N.N.W. ] of the pillar and near its base 2 pulleys on either side (i.e., four pulleys in all).

The pulleys on the east and west should be set up (in two rows, the first row of three on each side being) four yards and (the second row at a distance of) seven yards6 [This clause as it stands in the manuscript is unintelligible. Compare text lines 15 and 16, folio 103(b).] (from the pillar).

Besides these, four piers should be constructed on either side of the pillar, by the side of the piers of the domes, thus;— near the upper extremity of the pillar, two piers, each twelve yards in height: five yards lower down (i.e., towards the base of the pillar) two piers, each eleven yards in height: five yards further down, two piers each ten yards in height; and [101-a] five yards further towards the base of the pillar, two piers, each nine yards in height.

And on the south, east and west sides (of the pillar) should he constructed a solid structure of the shape of a tower or bastion ([illegible]) eight yards in height. The pullers should then be turned; the labars use their sang sticks, and the people exert themselves to raise the pillar. As soon as the upper extremity of the pillar has been raised one yard above the (levelled) surface, a stone-in-mud structure may be constructed under it at once. When this structure is completed, the ropes of the pulleys may be pulled again and as the upper end of the pillar rises higher and higher the stone-in-mud structure should also be raised. When the pillar arrives in front (i.e., about the level) of the twelve yard pier the beam and wheel may be removed from that pier and a sloping pasheb in stone-and-mud constructed under the column. Now the ropes of the pulleys should again be pulled; and three more wheels and three more pulleys should be set up on either side of the pillar, and the ropes pulled. When the pillar has been raised five yards higher, the upper one-third of it will reach the beam of the eleven yard pier. From this pier the beam, wheels, etc., should now be removed. The King's orders were obeyed and the pillar reached (the top level of) this pier. (The King then ordered that) all the ropes which were tied to the lower one-third of the pillar should be turned about (i.e., shifted) and tied to the upper one-third only: and that all the wheels, the ropes of which have any inclination towards the lower end of the pillar, should be set up near the upper end so that the angle of inclination of the lower end of the pillar may not be more than is really desirable. So it was done and the pillar (i.e., its upper end) was raised another 5 yards and nearly to a vertical position. But as on three sides of the pillar was a stone structure and the King feared lest the pillar base should strike against the stones with a sudden force and be injured, which God forbid, according to the King's orders and to alleviate his [104-b] fears, the pillar was tied with 35 strong ropes to the two masonry piers in front of it and instructions were given that these ropes should be tied correctly so that while permitting the pillar to be raised to the perpendicular position they would prevent it from striking (against the stones around its base). And that a large pillow of sackcloth ten yards long and one yard in diameter should be filled with grass and placed between the pillar and the surrounding stone structure, so that the pillar should move slowly without striking against the stone structure with a sudden force. So it was done: (and) on Wednesday the 4th of the month of Safar. 769 (A.H.) (=30th September, 1367 A.C.) the pillar stood erect in the desired position. The same day, according to the Royal orders, the two stones on the north which were kept ready for the purpose, were also fixed at the base of the pillar which was thus enclosed by stones to a height of two yards on all sides. No other man's schemes, not even a word from any wise man, engineer, architect, mason, or labourer1 [The words sut-har, dami and kami used in the manuscript for masons and labourers are all Hindi words.] had anything whatsoever to do with this achievement. From the scheme of taking down the pillar, its transportation by boats, removal to the boats and from the boats to the fort, and its re-erection therein, as well as the construction of the building on which it was erected, every one of these works was done exactly according to the orders and suggestions of His Majesty the King, the refuge of Faith, may God give him power always to preserve and establish pious institutions (for public welfare). Amen!

Then on the north side, too, which was vacant up to that time, was constructed a bastion of stone-in-mortar above the stones surrounding the pillar base so that the pillar was enclosed by solid structures on all sides to a height of eight yards. Then, all the pulleys and piers, supports and buttresses, everything in short set up for erecting the pillar, [105-a] were pulled down with the exception of the four masonry piers around the pillar. After this, a pavement of coloured stones was laid all round the monolith which was gilded, and a gilt finish seven and a half yards in height, and consisting of a pedestal (kursi [x]) a myrobalan-shaped ornament (halila [x]), a flat moulding (tas [x]), a dentil reel ([x]), a vase (suba [x]), a second reel and smaller vase (subuchah [x]) and a third reel, a flask (surahi [x]) and a crescent (mah [x]), was put up on the top of the pillar as the crowning ornament2. [Afif (Tarikh-i-Firozshahi, p. 302) says that the vases, etc., of the finial were made of copper and gilded over.] Then the covering of reeds which had been wrapped and bound all round the body of the pillar since the 10th of the month (of Muharram) was removed, and, as it was removed, the men repolished the pillar before descending. After this the four masonry piers were also dismantled. Then the King sent for the wise men and for his engineers, architects and masons and said. “This lofty pillar, while it was standing on the ground, was buried in the foundations to a depth of three yards, but now that it has been erected on the top of such a lofty building, only two yards of it is fixed in the masonry, though in fact it ought to have been more firmly fixed here. But if more of it is taken down or fixed into the masonry, its height will decrease. What should be done that it may be firmly fixed and yet not lose anything of its present height." Everyone was bewildered and considered it to be impossible. Deep as they dug into the depths of thought and imagination, and much as they tried to find an answer worth presenting, they succeeded not. With the perfection of understanding which the Almighty God has bestowed upon His Majesty, the refuge of the country, the King ordered that up to a height of two yards and a half the pillar should be enclosed on each side by six stones placed one above the other, each upper stone being recessed a third of a yard and the whole constructed and arranged like the pedestal of a candlestand. Thus, it would be a further support for the pillar which will be more firmly fixed and as each upper stone will recede half a yard it will not detract anything from the height of the monolith. At this speech [105-h] all began to bless the King, praying for the eternal existence of his powerful Kingdom; and the stones were arranged in steps according to the Royal instructions.

Then, at the base of the pillar, was laid the pavement of coloured stones — white marble, red stone (sang-i-Maryam) and black-stone, which were brought from all parts of the country; the temporary buildings constructed for the erection of the pillar, were dismantled; and the structure with the domes forming the uppermost storey, was provided with staircases and (finished); then the building of the middle storey described above was completed and decorated (paved): and, last of all, the lowest storey was taken up and similarly finished.

After this a corridor (sabat) was built between the mosque and the pillar which latter now stood within the outer enclosure of the mosque. And after it had remained an object of worship of the polytheists and infidels for so many thousands of years, through the efforts of Sultan Firoz Shah and by the grace of God, it became the minar of a place of worship (masjid) for the Faithful. May God make this mighty Kingdom rich with the treasure of rewards and strengthen its supports. All praise is due to God.

(And from the taking down of this heavy pillar from its old site to its re-erection at Firozabad), none but his Majesty, whose rule be perpetuated, had any say in the matter of general plans or particular details.