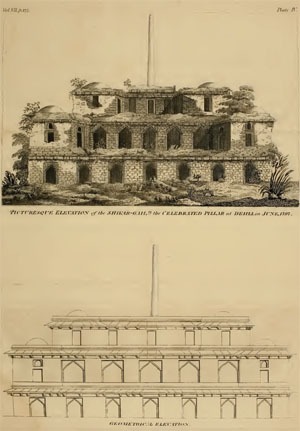

Plate IV: Picturesque Elevation of the Shikar-Gah, & the Celebrated Pillar at Dehli in June, 1797

-- Translation of one of the Inscriptions on the Pillar At Dehlee, called the Lat of Feeroz Shah, Excerpt from Asiatic Researches, Volume 7, by Henry Colebrooke, Esq., With Introductory Remarks by Mr. Harington. P. 175-182, 1808

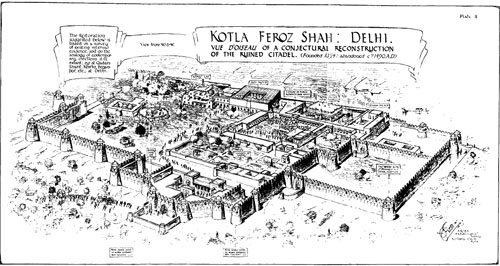

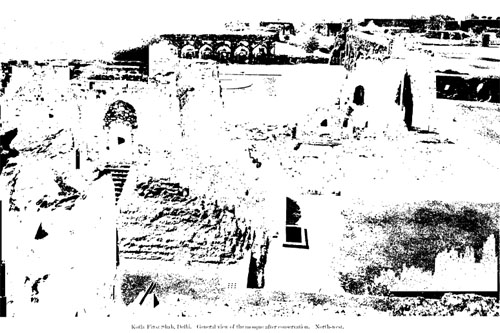

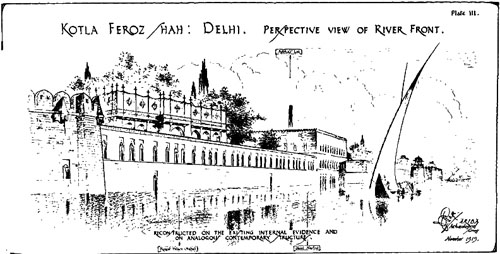

An illustration of the Lat pyramid in the Asiatic Researches of the year 1802 (reproduced in Plate IV, Vol. VIII [1803, Vol. VII?) shews it in a much better state of preservation than it is at present (Plate V), and depicts the low flat domes reproduced over the corner pavilions containing the ascending stairs. The top colonnade indicated in the perspective view (Plate III) is more conjectural, but evidence of the existence of a feature of this kind is apparent in the presence of a pair of broken columns still remaining in situ on the western edge of the roof.

Plate III. Kotla FerozShah: Delhi. Perspective View of River Front. Reconstructed on the Existing Internal Evidence and on Analogous Contemporary Structure. November 1919.

The pyramid on which the Lat stands consists of 3 terraces progressively decreasing in size1, [The first terrace measures 118' square, the second 83' square, and the third 55' square.] and giving the building a stepped appearance. On each terrace is a series of vaulted cells surrounding the solid core of the structure into which the foot of the Lat of Asoka is built2. [It is not within the province of this memoir to give an account of the Mauryan Emperor Asoka. “He erected the granite pillars which bore the edicts spreading this new religion from Kabul to Orissa.” The dates of his accession and death are given by Sir John Marshall (A Guide to Taxila) as 273 and 232 B.C. respectively.]

The Lat is a sandstone monolith 42' 7" in height, 35' being polished3 [The polish on the surface of Asokan columns and sculptures is a very characteristic feature — a technique which had its origin in Persepolis where abundant examples still survive. (See “A Guide to Sanchi”, p. 92, by Sir John Marshall.)] and the remainder rough; the buried portion measures some 4' ", and Cunningham is of the opinion that the rough portion, standing above the level of the terrace, was buried in the ground in its original site. According to Shams-i-Siraj, one quarter of the monolith was hidden by the masonry of the pyramid originally, and Cunningham believes this to have been actually the case, owing to the existence of the stumps of the octagonal columns previously described, which would appear to have formed a cloister or open gallery round the topmost storey. The diameter of the Lat is 25.3 inches at the top and 38.3 inches at the base, the diminution being .39" per foot. It is said to weight 27 tons; while the colour of the sandstone is pale orange, flecked with black spots. Major Burt who examined it in 1837 gives its measurements as 35' in length with a diameter of 3-1/4 feet; Franklin (As. Res.) a length of 50': Von Orlich, 42': William Finch. 24': Shams- i-Siraj, 34', and its circumference 10'. In the matter of dimensions it resembles the Allahabad pillar more than any other, but it tapers more rapidly towards the top and is, therefore, less graceful in outline (Cunningham). Tom Coryat and Whittaker (Kerr's Voyages and Travels. IX. 423) state that the pillar was of brass; the chaplain Edward Terry records that it was of marble with a Greek inscription4 [A translation of this inscription, which is in Pali character is given in the Appendix.] upon it, while Bishop Heber says that it was on "cast metal." Timur declared that he had never seen any monument in all the numerous lands he had traversed comparable to these monoliths.

The Tarikh-i-Firozshahi gives the following account of the erection of the lat of Asoka in Firozabad:

"After5 [Elliott & Dowson, Vol. III, p. 350, Tarikh-i-Firozshahi, Shams-i-Siraj, Afif.] Sultan Firoz returned from his expedition against Thatta he often made excursions in the neighbourhood of Dehli. In the part of the country there were two stone columns. One was in the village of Tobra, in the district (shikk) of Salaura and Khizrabad in the hills (koh-payah), the other in the vicinity of the town of Mirat. These columns had stood in those places from the days of the Pandavas, but had never attracted the attention of any of the kings who sat upon the throne of Delhi, till Sultan Firoz noticed them, and, with great exertion, brought them away. One was erected in the palace (kushk) at Firozabad, near the Masjid-i-jama, and was called the Minara-i-Zarrin, or Golden Column, and the other was erected in the Kushk-i-Shikar, or Hunting Palace, with great labour and skill. The author has read in the works of good historians that these columns of stone had been the walking sticks of the accursed Bhim a man of great stature and size. The annals of the infidels record that this Bhim used to devour a thousand mans of food daily, and no one could compete with him ..... In his days all this part of Hind was peopled with infidels, who were continually fighting and slaying each other. Bhim was one of five brothers, but he was the most powerful of them all. He was generally engaged in tending the herds of cattle belonging to his wicked brothers, and he was accustomed to use these two stone pillars as sticks to gather the cattle together. The size of the cattle in those days was in proportion to that of other creatures. These five brothers lived near Delhi, and when Bhim died these two columns were left standing as memorials of him .....

Removal of the Minara-i-Zarrin. — Khizrabad is 90 kos from Dehli, in the vicinity of the hills. When the Sultan visited that district, and saw the column in the village of Tobra, he resolved to remove it to Delhi, and there erect it as a memorial of future generations. After thinking over the best means of lowering the column, orders were issued commanding the attendance of all the people dwelling in the neighbourhood, within and without the Doab, and all soldiers, both horse and foot. They were ordered to bring all implements and materials suitable for the work. Directions were issued for bringing parcels of the cotton of the Sembal (silk cotton tree). Quantities of this silk cotton were placed round the column, and when the earth at its base was removed, it fell gently over on the bed prepared for it. The cotton was then removed by degrees, and after some days the pillar lay safe upon the ground. When the foundations of the pillar were examined, a large square stone was found as a base, which also was taken out. The pillar was then encased from top to bottom in reeds and raw skins so that no damage might accrue to it. A carriage, with forty-two wheels, was constructed, and ropes were attached to each wheel. Thousands of men hauled at every rope, and after great labour and difficulty the pillar was raised on to the carriage. A strong rope was fastened to each wheel, and 200 men pulled at each of these ropes. By the simultaneous exertions of so many thousand men the carriage was moved, and was brought to the banks of the Jumna. Here the Sultan came to meet it. A number of large boats had been collected, some of which could carry 5,000 and 7,000 mans of grain, and the least of them 2,000 mans. The column was very ingeniously transferred to these boats, and was then conducted to Firozabad, where it was landed and conveyed into the Kushk with infinite labour and skill.

Account of the Raising of the Obelisk. —

At this time the author of this book was twelve years of age, and a pupil of the respected Mur Khan. When the pillar was brought to the palace, a building was commenced for its reception, near the Jami Masjid, and the most skilful architects and workmen were employed. It was constructed of stone and chunam, and consisted of several stages or steps (poshish). When a step was finished the column was raised on to it, another step was then built and the pillar was again raised, and so on in succession until it reached the intended height. On arriving at this stage, other contrivances had to be devised to place it in an erect position. Ropes of great thickness were obtained, and windlasses were placed on each of the six stages of the base. The ends of the ropes were fastened to the top of the pillar, and the other ends passed over the windlasses, which were firmly secured with many fastenings. The wheels were then turned, and the column was raised about half a gzz. Logs of wood and bags of cotton were then placed under it to prevent its sinking again. In this way, by degrees, and in the course of several days, the column was raised to the perpendicular. Large beams were then placed round it as shores, until quite a cage of scaffolding was formed. It was thus secured in an upright position, straight as an arrow, without the smallest deviation from the perpendicular. The square stone, before spoken of, was placed under the pillar. After it was raised, some ornamental friezes of black and white stone were placed round its two capitals (do sar-i-an) and over these there was raised a gilded copper cupola, called in Hindi kalas. The height of the obelisk was thirty-two gaz; eight gaz was sunk in its pedestal, and twenty-four gaz was visible. On the base of the obelisk there were engraved several lines of writing1 [See Appendix.] in Hindi characters. Many Brahmans and Hindu devotees were invited to read them, but no one was able. It is said that certain infidel Hindus interpreted them as stating that no one should be able to remove the obelisk from its place till there should arise in the latter days a Muhammadan King, named Sultan Firoz, etc., etc."