Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlik Shah, the heir apparent, succeeded his father, and ascended the throne at Tughlikabad in the year 725 H. (1325 A.D.)....

The dogmas of philosophers, which are productive of

indifference and hardness of heart, had a powerful influence over him. But the declarations of the holy books, and the utterances, of the Prophets, which inculcate

benevolence and humility, and hold out the prospect of future punishment,

were not deemed worthy of attention. The punishment of Musulmans, and the execution of true believers, with him became a practice and a passion. Numbers of doctors, and elders, and saiyids, and sufis, and kalandars, and clerks, and soldiers, received punishment by his order. Not a day or week passed without the spilling of much Musulman blood, and the running of streams of gore before the entrance of his palace....If I were to write a full account of all the affairs of his reign, and of all that passed, with his faults and shortcomings, I should fill many volumes.

In this history I have recorded all the great and important matters of his reign, and the beginning and the end of every conquest; but the rise and termination of every mutiny, and of events (of minor importance), I have passed over. ***

Sultan Muhammad planned in his own breast three or four projects by which the whole of

the habitable world was to be brought under the rule of his servants, but he never talked over these projects with any of his councillors and friends. Whatever he conceived he considered to be good, but in promulgating and enforcing his schemes

he lost his hold upon the territories he possessed, disgusted his people, and emptied his treasury. Embarrassment followed embarrassment, and confusion became worse confounded. The ill feeling of the people gave rise to outbreaks and revolts. The rules for enforcing the royal schemes became daily more oppressive to the people. More and more the people became disaffected, more and more the mind of the king was set against them, and the numbers of those brought to punishment increased. The tribute of most of the distant countries and districts was lost, and many of the soldiers and servants were scattered and left in distant lands. Deficiencies appeared in the treasury. The mind of the Sultan lost its equilibrium. In the extreme weakness and harshness of his temper he gave himself up to severity. Gujarat and Deogir were the only (distant) possessions that remained. In the old territories, dependent on Dehli, the capital, disaffection and rebellion sprung up. By the will of fate

many different projects occurred to the mind of the Sultan, which appeared to him moderate and suitable, and were enforced for several years, but the people could not endure them. These schemes effected the ruin of the Sultan's empire, and the decay of the people. Every one of them that was enforced wrought some wrong and mischief, and the minds of all men, high and low, were disgusted with their ruler. Territories and districts which had been securely settled were lost. When the Sultan found that his orders did not work so well as he desired, he became still more embittered against his people. He cut them down like weeds and punished them. So many wretches were ready to slaughter true and orthodox Musalmans as had never before been created from the days of Adam. * * *

If the twenty prophets had been given into the hands of these minions, I verily believe that they would not have allowed them to live one night....The first project which the Sultan formed, and which operated to the ruin of the country and the decay of the people, was that

he thought he ought to get ten or five per cent, more tribute from the lands in the Doab. To accomplish this he invented some oppressive abwabs (cesses), and made stoppages from the land-revenues until

the backs of the raiyats were broken. The cesses were collected so rigorously that

the raiyats were impoverished and reduced to beggary. Those who were rich and had property became rebels;

the lands were ruined, and cultivation was entirely arrested. When the raiyat in distant countries heard of the distress and ruin of the raiyats in the Doab, through fear of the same evil befalling them, they threw off their allegiance and betook themselves to the jungles. The decline of cultivation, and the distress of the raiyats in the Doab, and the failure of convoys of corn from Hindustan,

produced a fatal famine in Dehli and its environs, and throughout the Doab, Grain became dear. There was a deficiency of rain, so the famine became general. It continued for some years, and

thousands upon thousands of people perished of want. Communities were reduced to distress, and families were broken up. The glory of the State, and the power of the government of Sultan Muhammad, from this time withered and decayed.

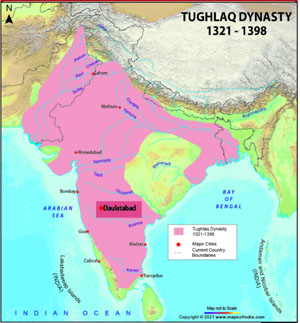

The second project of Sultan Muhammad, which was ruinous to the capital of the empire, and distressing to the chief men of the country, was that of making Deogir his capital, under the title of Daulatabad. This place held a central situation: Dehli, Gujarat, Lakhnauti, Sat-ganw, Sunar-gauw, Tilang, Ma'bar, Dhur-samundar, and Kampila were about equi-distant from thence, there being but a slight difference in the distances. Without any consultation, and without carefully looking into the advantages and disadvantages on every side,

he brought ruin upon Dehli, that city which, for 170 or 180 years, had grown in prosperity, and rivaled Baghdad and Cairo. The city, with its sarais and its suburbs and villages, spread over four or five kos.

All was destroyed. So complete was the ruin, that not a cat or a dog was left among the buildings of the city, in its palaces or in its suburbs. Troops of the natives, with their families and dependents, wives and children, men-servants and maid-servants, were forced to remove. The people, who for many years and for generations had been natives and inhabitants of the land, were broken-hearted. Many, from the toils of the long journey, perished on the road, and those who arrived at Deogir could not endure the pain of exile. In despondency they pined to death. All around Deogir, which is an infidel land, there sprung up graveyards of Musulmans. The Sultan was bounteous in his liberality and favours to the emigrants, both on their journey and on their arrival; but they were tender, and they could not endure the exile and suffering. They laid down their heads in that heathen land, and of all the multitudes of emigrants, few only survived to return to their home. Thus this city, the envy of the cities of the inhabited world, was reduced to ruin. The Sultan brought learned men and gentlemen, tradesmen and landholders, into the city (Dehli) from certain towns in his territory, and made them reside there. But this importation of strangers did not populate the city; many of them died there, and more returned to their native homes. These changes and alterations were the cause of great injury to the country.

The third project also did great harm to the country. It increased the daring and arrogance of the disaffected in Hindustan, and augmented the pride and prosperity of all the Hindus. This was the issue of copper money.

The Sultan, in his lofty ambition, had conceived it to be his work to subdue the whole habitable world and bring it under his rule. To accomplish this impossible design, an army of countless numbers was necessary, and this could not be obtained without plenty of money. The Sultan's bounty and munificence had caused a great deficiency in the treasury, so he introduced his copper money, and gave orders that it should be used in buying and selling, and should pass current, just as the gold and silver coins had passed. The promulgation of this edict turned the house of every Hindu into a mint, and the Hindus of the various provinces coined krors and lacs of copper coins. With these they paid their tribute, and with these they purchased horses, arms, and fine things of all kinds. The rais, the village headmen and landowners, grew rich and strong upon these copper coins, but the State was impoverished. No long time passed before distant countries would take the copper tanka only as copper. In those places where fear of the Sultan's edict prevailed, the gold tanka rose to be worth a hundred of (the copper) tankas. Every goldsmith struck copper coins in his workshop, and the treasury was filled with these copper coins.

So low did they fall that they were not valued more than pebbles or potsherds. The old coin, from its great scarcity, rose four-fold and five-fold in value. When

trade was interrupted on every side, and when the copper tankas had become more worthless than clods, and of no use, the Sultan repealed his edict, and in great wrath he proclaimed that whoever possessed copper coins should bring them to the treasury, and receive the old gold coins in exchange. Thousands of men from various quarters, who possessed thousands of these copper coins, and caring nothing for them, had flung them into corners along with their copper pots, now brought them to the treasury, and received in exchange gold tankas and silver tankas, shash-ganis and du-ganis, which they carried to their homes. So many of these copper tankas were brought to the treasury, that

heaps of them rose up in Tughlikabad like mountains. Great sums went out of the treasury in exchange for the copper, and a great deficiency was caused. When the Sultan found that his project had failed, and that great loss had been entailed upon the treasury through his copper coins, he more than ever turned against his subjects.

The fourth project which diminished his treasury, and so brought distress upon the country, was

his design of conquering Khurasan and 'Irak. In pursuance of this object, vast sums were lavished upon the officials and leading men of those countries. These great men came to him with insinuating proposals and deceitful representations, and as far as they knew how, or were able, they robbed the throne of its wealth.

The coveted countries were not acquired, but those which he possessed were lost; and his treasure, which is the true source of political power, was expended.

The fifth project * * * was the rising of an immense army for the campaign against Khurasan. * * * In that year three hundred and seventy thousand horse were enrolled in the muster-master's office. For a whole year these were supported and paid; but as they were not employed in war and conquest and enabled to maintain themselves on plunder, when the next year came round, there was not sufficient in the treasury or in the feudal estates (ikta) to support them. The army broke up; each man took his own course and engaged in his own occupations. But lacs and krors had been expended by the treasury.

The sixth project, which inflicted a heavy loss upon the army, was

the design which he formed of capturing the mountain of Kara-jal. His conception was that, as he had undertaken the conquest of Khurasan, he would (first) bring under the dominion of Islam this mountain, which lies between the territories of Hind and those of China, so that the passage for horses and soldiers and the march of the army might be rendered easy. To effect this object

a large force, under distinguished amirs and generals, was sent to the mountain of Kara-jal, with orders to subdue the whole mountain. In obedience to orders, it marched into the mountains and encamped in various places, but

the Hindus closed the passes and cut off its retreat. The whole force was thus destroyed at one stroke, and out of all this chosen body of men only ten horsemen returned to Delhi to spread the news of its discomfiture....

The first revolt was that of Bahram Abiya at Multan....At this time

the country of the Doab was brought to ruin by the heavy taxation and the numerous cesses. The Hindus burnt their corn stacks and turned their cattle out to roam at large. Under the orders of the Sultan,

the collectors and magistrates laid waste the country, and they killed some landholders and village chiefs and blinded others. Such of these unhappy inhabitants as escaped formed themselves into bands and took refuge in the jungles. So

the country was ruined. The Sultan then proceeded

on a hunting excursion to Baran, where, under his directions, the whole of that country was plundered and laid waste, and the heads of the Hindus were brought in and hung upon the ramparts of the fort of Baran.About this time the rebellion of Fakhra broke out in Bengal, after the death of Bahram Khan (Governor of Sunar-ganw).... At the same period

the Sultan led forth his army to ravage Hindustan. He laid the country waste from Kanauj to Dalamu, and every person that fell into his hands he slew. Many of the inhabitants fled and took refuge in the jungles, but the Sultan had the jungles surrounded, and every individual that was captured was killed.

While he was engaged in the neighbourhood of Kanauj a third revolt broke out....

When the Sultan arrived at Deogir he made heavy demands upon the Musulman chiefs and collectors of the Mahratta country, and his oppressive exactions drove many persons to kill themselves....

The Sultan proceeded to Dhar, and being still indisposed, he rested a few days, and then pursued his journey through Malwa. Famine prevailed there, the posts were all gone off the road, and

distress and anarchy reigned in all the country and towns along the route. When the Sultan reached Dehli, not a thousandth part of the population remained. He found the country desolate, a deadly famine raging, and all cultivation abandoned. He employed himself some time in restoring cultivation and agriculture, but the rains fell short that year, and no success followed. At length no horses or cattle were left; grain rose to 16 or 17 jitals a sir, and

the people starved. The Sultan advanced loans from the treasury to promote cultivation, but men had been brought to a state of helplessness and weakness. Want of rain prevented cultivation, and the people perished....

From thence he went to Agroha, where he rested awhile, and afterwards to Dehli, where

the famine was very severe, and man was devouring man....The Sultan again marched to Sannam and Samana, to put down the rebels, who had formed mandals (strongholds?), withheld the tribute, created disturbances, and plundered on the roads....

While this was going on a revolt broke out among the Hindus at Arangal. Kanya Naik had gathered strength in the country. Malik Makbul, the naib-wazir, fled to Dehli, and

the Hindus took possession of Arangal, which was thus entirely lost.... The land of Kambala also was thus lost, and fell into the hands of the Hindus....About this time, during the Sultan's stay at Dehli and his temporary residence at Sarg-dwari,

four revolts were quickly repressed. First. That of Nizam Ma-in at Karra. *** 'Ainu-l Mulk and his brothers marched against this rebel, and having put down the revolt and made him prisoner, they flayed him and sent his skin to Dehli....Many of the fugitives, in their panic, cast themselves into the river and were drowned. The pursuers obtained great booty. Those who escaped from the river fell into the hands of the Hindus in the Mawas and lost their horses and arms....

When the Sultan returned to Dehli, it occurred to his mind that no king or prince could exercise regal power without confirmation by the Khalifa of the race of 'Abbas, and that every king who had, or should hereafter reign, without such confirmation, had been or would be overpowered....The Sultan directed that a letter acknowledging his subordination to the Khalifa should be sent by the hands of Haji Rajab Barka'i, * * * and after two years of correspondence the Haji returned from Egypt, bringing a diploma in the name of the Sultan, as deputy of the Khalifa....

The Sultan supported and patronized the Mughals. Every year at the approach of winter, the amirs of tumans (of men) and of thousands etc., etc., received krors and lacs, and robes, and horses, and pearls. During the whole period of two or three years, the Sultan was intent upon patronizing and favouring the Mughals....

He applied himself excessively to the business of punishment, and this was the cause of many of the acquired territories slipping from his grasp, and of troubles and disturbances in those which remained in his power. *** The more severe the punishments that were inflicted in the city, the more disgusted were the people in the neighbourhood, insurrections spread, and the loss and injury to the State increased. Every one that was punished spoke evil of him...The Sultan having thus appointed the base-born 'Aziz Himar to Dhar and Malwa, gave him several lacs of tankas on his departure, in order that he might proceed thither with befitting state and dignity. * * * He said to him, "Thou seest how that revolts and disturbances are breaking out on every side, and I am told that whoever creates a disturbance does so with the aid of the foreign amirs. *** Revolts are possible, because these amirs are ready to join any one for the sake of disturbance and plunder. If you find at Dhar any of these amirs, who are disaffected and ready to rebel, you must get rid of them in the best way you can." 'Aziz arrived at Dhar, and in all his native ignorance applied himself to business. The vile whoreson one day got together about

eighty of the foreign amirs and chiefs of the soldiery, and, upbraiding them with having been the cause of every misfortune and disturbance, he had them

all beheaded in front of the palace. * * * This slaughter of the foreign amirs of Dhar, on the mere ground of their being foreigners,

caused those of Deogir, and Gujarat, and every other place to unite and to break out into insurrection. *** When the Sultan was informed of this punishment, he sent 'Aziz a robe of honour and a complimentary letter....

About the time when this horrid tragedy was perpetrated by 'Aziz Himar, the naib-wazir of Gujarat, Mukbil by name, having with him the treasure and horses which had been procured in Gujarat for the royal stables, was proceeding by way of Dihui and Baroda to the presence of the Sultan....

The amirs having acquired so many horses and so much property grew in power and importance. Stirring up the flames of insurrection, they gathered together a force and proceeded to Kanhayat (Cambay). The news of their revolt spread throughout Gujarat, and the whole country was falling into utter confusion. At the end of the month of Ramazan, 745 H. (Feb. 1345), the intelligence of this revolt and of the defeat and plunder of Mukbil was brought to the Sultan. It caused him much anxiety, and he determined to proceed to Gujarat in person to repress the revolt....

He appointed Firoz, afterwards Sultan, Malik Kabir, and Ahmad Ayyaz to be vicegerents in the capital during his absence....Insurrection followed upon insurrection. During the four or five days of Ramazan that the Sultan halted at Sultanpur, late one evening he sent for the author of this work, Zia Barni...."You have read many histories; hast thou found that kings inflict punishments under certain circumstances?" I replied, "I have read in royal histories that

a king cannot carry on his government without punishments, for if he were not an avenger God knows what evils would arise from the insurrections of the disaffected, and how many thousand crimes would be committed by his subjects. Jamshid was asked under what circumstances punishment is approved. He replied, 'under seven circumstances, and whatever goes beyond or in excess of these causes, produces disturbances, trouble, and insurrection, and inflicts injury on the country...

The servants of God are disobedient to him when they are disobedient to the king, who is his vicegerent; and the State would go to ruin, if the king were to refrain from inflicting punishment in such cases of disobedience as are injurious to the realm.'" ... The Sultan replied, ''Those punishments which Jamshid prescribed were suited to the early ages of the world, but in these days

many wicked and turbulent men are to be found. I visit them with chastisement upon the suspicion or presumption of their rebellious and treacherous designs, and I punish the most trifling act of contumacy with death. This I will do until I die, or until the people act honestly, and give up rebellion and contumacy. I have no such wazir as will make rules to obviate my shedding blood.

I punish the people because they have all at once become my enemies and opponents. I have dispensed great wealth among them, but they have not become friendly and loyal. Their temper is well known to me, and I see that they are disaffected and inimical to me."

The Sultan marched from Sultanpur towards Gujarat, and when he arrived at Nahrwala he sent Shaikh Ma'izzu-d din, with some officials, into the city, whilst he, leaving it on the left, proceeded into the mountains of Abhu to which Dihui and Baroda were near. The Sultan then sent an officer with a force against the rebels, and these being unable to cope with the royal army, were defeated....The Sultan then proceeded from the mountains of Abhu to Broach from whence he sent Malik Makbul ...

The Sultan remained for some time at Broach, busily engaged in collecting the dues of Broach, Kanhayat (Cambay), and Gujarat, which were several years in arrear.

He appointed sharp collectors, and rigorously exacted large sums. At this period

his anger was still more inflamed against the people, and revenge filled his bosom. Those persons at Broach and Cambay, who had disputed with Malik Makbul, or had in any way encouraged insurrection, were seized and consigned to punishment. Many persons of all descriptions thus met their ends.

While the Sultan was at Broach

he appointed Zin-banda and the middle son of Rukn Thanesari, two men who were leaders in iniquity and the most depraved men in the world, to inquire into the matters of the disaffected at Deogir. Pisar Thanesari, the vilest of men, went to Deogir; and Zin-banda, a wicked iniquitous character, who was called Majdu-l Mulk, was on the road thither. A murmuring arose among the Musulmans at Deogir that two vile odious men had been deputed to investigate the disaffection, and to bring its movers to destruction....They marched toward Broach, but at the end of the first stage the foreign amirs, who were attended by their own horsemen, considered that they had been summoned to Broach in order to be executed, and if they proceeded thither not one would return. So they consulted together and broke out into open resistance, and the two nobles who had been sent for them were killed in that first march. They then turned back with loud clamour and entered the royal palace, where they seized Maulana Nizamu-d din, the governor, and put him in confinement.

The officials, who had been sent by the Sultan to Deogir, were taken and beheaded. They cut Pisar Thanesari to pieces, and brought down the treasure from (the fort of) Dharagir. Then they made Makh Afghan, brother of Malik Yak Afghan, one of the foreign amirs, their leader, and placed him on the throne. The money and treasure were distributed among the soldiers. The Mahratta country was apportioned among these foreign amirs, and several disaffected persons joined the Afghans. The foreign amirs of Dihui and Baroda left Man Deo and proceeded to Deogir, where the revolt had increased and had become established. The people of the country joined them.

The Sultan, on hearing of this revolt, made ready a large force and arrived at Deogir, where the rebels and traitors confronted him. He attacked them and defeated them. Most of the horsemen were slain in the action....The inhabitants of Deogir, Hindus and Musulmans, traders and soldiers, were plundered....

[N]ews arrived of

the revolt, excited by the traitor Taghi, in Gujarat. This man was a cobbler, and had been a slave of the general, Malik Sultani. He had won over the foreign amirs of Gujarat, and had broken out into rebellion. Many of the mukaddims of Gujarat joined him....

I, Zia Barni, the author of this history, just at this time joined the Sultan, after he had made one or two marches from Ghati-sakun towards Broach. I had been sent from the capital by the present Sultan (Firoz), Malik Kabir, and Ahmad Ayyaz, with letters of congratulation on the conquest of Deogir. The Sultan received me with great favour. One day, as I was riding in his suite, the Sultan conversed with me, and the conversation turned upon rebellion. He then said, "Thou seest what troubles these traitorous foreign amirs have excited on every side. When I collect my forces and put them down in one direction, they excite disturbances in some other quarter. If I had at the first given orders for the destruction of all the foreign amirs of Deogir, Gujarat, and Broach, I should not have been so troubled by them. This rebel, Taghi, is my slave; if I had executed him or had sent him as a memorial to the King of Eden, this revolt would never have broken out." I could not help feeling a desire to tell the Sultan that the troubles and revolts which were breaking out on every side, and this general disaffection, all arose from the excessive severity of his Majesty, and that if punishments were suspended for a while, a better feeling might spring up, and mistrust be removed from the hearts of the people. But I dreaded the temper of the king, and could not say what I desired, so I said to myself, What is the good of pointing out to the Sultan the causes of the troubles and disturbances in his country, for it will have no effect upon him?...

Taghi, with his remaining horsemen, reached Nahrwala; there he collected all his family and dependents, and proceeded to Kant-barahi...

While the Sultan was engaged in settling the affairs of the country, and was about to enter Nahrwala, news came from Deogir that Hasan Kangu and other rebels, who had fled before the royal army in the day of battle, had since attacked 'Imadu-l Mulk, and had slain him and scattered his army. Kiwamu-d din and other nobles left Deogir and went towards Dhar. Hasan Kangu then proceeded to Deogir and assumed royal dignity. Those rebels who had fled before the Sultan's army to the summit of Dharagir, now came down, and

a revolution was effected in Deogir. When intelligence of this reached the Sultan's ears, he was very disheartened, for he saw very well that

the people were alienated. No place remained secure, all order and regularity were lost, and the throne was tottering to its fall....The success of the rebels, and the loss of Deogir, greatly troubled the king. One day, while he was thus distressed, he sent for me, the author of this work, and, addressing me, said: "My kingdom is diseased, and no treatment cures it. The physician cures the headache, and fever follows; he strives to allay the fever, and something else supervenes. So in my kingdom disorders have broken out; if I suppress them in one place they appear in another; if I allay them in one district another becomes disturbed. What have former kings said about these disorders?" I replied,...

The Sultan replied, "If I can settle the affairs of my kingdom according to my wish, I will consign my realm of Dehli to three persons, Firoz Shah, Malik Kabir, and Ahmad Ayyaz, and I will then proceed on the pilgrimage to the holy temple. At present I am angry with my subjects, and they are aggrieved with me. The people are acquainted with my feelings, and I am aware of their misery and wretchedness. No treatment that I employ is of any benefit.

My remedy for rebels, insurgents, opponents, and disaffected people is the sword. I employ punishment and use the sword, so that a cure may be effected by suffering. The more the people resist, the more I inflict chastisement."...

[H]e resolved to make Taghi prisoner and deliver him up...After the rains were over, the Sultan took Karnal, and brought all the coast into subjection.... Before the Sultan went to Kondal he received from Dehli the intelligence of the death of Malik Kabir, which deeply grieved him. Thereupon he sent Ahmad Ayyaz and Malik Makbul from the army to take charge of the affairs of the capital. He summoned Khudawand-zada, Makhdum-zada, and many elders, learned men and others, with their wives and families, to Kondal. Every one that was summoned hastened with horse and foot to join the Sultan at Kondal, so that a large force was gathered there and was formed into an army. Boats were brought from Deobalpur, Multan, Uch, and Siwistan to the river.

The Sultan recovered from his disorder, and

marched with his army to the Indus. He crossed that river in ease and safety with his army and elephants.

He was there joined by Altun Bahadur, with four or five thousand Mughal horse, sent by the Amir of Farghan. The Sultan showed great attention to this leader and his followers, and bestowed many gifts upon them. He then advanced along the banks of the Indus towards Thatta, with an army as numerous as a swarm of ants or locusts, with the intention of humbling the Sumras and the rebel Taghi, whom they had sheltered.

As he was thus marching with his countless army, and was thirty kos from Thatta, the 'ashura or fast of the 10th of Muharram happened. He kept the fast, and when it was over

he ate some fish. The fish did not agree with him, his illness returned and fever increased. He was placed in a boat and continued his journey on the second and third days, until he came to within fourteen kos of Thatta. He then rested, and his army was fully prepared, only awaiting the royal command to take Thatta, and to crush the Sumras of Thatta and the rebel Taghi in a single day, and to utterly annihilate them. But fate ruled it otherwise. During the last two or three days that he was encamped near Thatta, the Sultan's malady had grown worse, and

his army was in great trouble, for they were a thousand kos distant from Dehli and their wives and children, they were near the enemy and in a wilderness and desert, so they were sorely distressed, and looking upon the Sultan's expected death as preliminary to their own, they quite despaired of returning home. On the 21st Muharram, 752 H. (1350 A.D.), Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlik departed this life on the banks of the Indus, at fourteen kos from Thatta....1. — Accession of Firoz Shah.

* * * On the third day after the death of Mahammad Tughlik, the army marched from (its position) fourteen kos from Thatta towards Siwistan, on its return homewards.

Every division of the army marched without leader, rule, or route, in the greatest disorder. No one heeded or listened to what any one said, but continued the march like careless caravans.

So when they had proceeded a kos or two, the Mughals, eager for booty, assailed them in front, and the rebels of Thatta attacked them in the rear. Cries of dismay arose upon every side. The Mughals fell to plundering, and carried off women, maids, horses, camels, troopers, baggage, and whatever else had been sent on in advance. They had very nearly captured the royal harem and the treasure with the camels which carried it. The villagers (who had been pressed into the service) of the army, and expected the attack, took to flight. They pillaged various lots of baggage on the right and left of the army, and then joined the rebels of Thatta in attacking the baggage train. The people of the army, horse and foot, women and men, stood their ground; for when they marched, if any advanced in front, they were assailed by the Mughals; if they lagged behind, they were plundered by the rebels of Thatta. Those who resisted and put their trust in God reached the next stage, but

those who had gone forward with the women, maids, and baggage, were cut to pieces. The army continued its march along the river without any order or regularity, and every man was in despair for his life and goods, his wife and children. Anxiety and distress would allow no one to sleep that night, and, in their dismay, men remained with their eyes fixed upon heaven. On the second day, by stratagem and foresight, they reached their halting ground, assailed, as on the first day, by the Mughals in front and the men of Thatta in the rear. They rested on the banks of the river in the greatest possible distress, and in fear for their lives and goods.

The women and children had perished. Makhdum Zada 'Abbasi, the Shaikhu-s Shaiyukh of Egypt, Shaikh Nasiru-d din Mahmud Oudhi, and the chief men, assembled and went to Firoz Shah, and with one voice said, "Thou art the heir apparent and legatee of the late Sultan; he had no son, and thou art his brother's son; there is no one in the city or in the army enjoying the confidence of the people, or possessing the ability to reign. For God's sake save these wretched people, ascend the throne, and deliver us and many thousand other miserable men. Redeem the women and children of the soldiers from the hands of the Mughals, and purchase the prayers of two lacs of people." Firoz Shah made objections, which the leaders would not listen to. All ranks, young and old, Musulmans and Hindus, horse and foot, women and children, assembled, and with one acclaim declared that Firoz Shah alone was worthy of the crown. "If he does not assume it to-day and let the Mughals hear of his doing so, not one of us will escape from the hands of the Mughals and the Thatta men." So on the 24th Muharram, 752 H. (1351 A.D.), the Sultan ascended the throne.On the day of his accession the Sultan got some horse in order and sent them out to protect the army, for whenever the Mughal horse came down they killed and wounded many, and carried off prisoners. On the same day he named some amirs to guard the rear of the army, and these attacked the men of Thatta when they fell upon the baggage. Several of the assailants were put to the sword, and they, terrified with this lesson, gave up the pursuit and returned home. On the third day he ordered certain amirs to attack the Mughals, and they accordingly made several of the Mughal commanders of thousands and of hundreds prisoners, and brought them before the Sultan. The Mughals from that very day ceased their annoyance; they moved thirty or forty kos away, and then departed for their own country.

-- XV. Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, of Ziaud Din Barni [Ziauddin Barani], Excerpt from The History of India As Told By Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, edited from the posthumous papers of the Late Sir H.M. Elliot, K.C.B., East India Company's Bengal Civil Service, by Professor John Dowson, M.R.A.S., Staff college, Sandhurst, Vol. III, P. 93-269, 1871