CHAPTER XXVI. RESULTS OF THE DISCOVERIES TO CHRONOLOGY AND HISTORY.—NAMES OF ASSYRIAN KINGS IN THE INSCRIPTIONS.—A DATE FIXED.—THE NAME OF JEHU.—THE OBELISK KING.—THE EARLIER KINGS.—SARDANAPALUS.—HIS SUCCESSORS.—PUL, OR TIGLATH PILESER.—SARGON.—SENNACHERIR.—ESSARHADDON.—THE LAST ASSYRIAN KINGS.—TABLES OF PROPER NAMES IN THE ASSYRIAN INSCRIPTIONS.—ANTIQUITY OF NINEVEH.—OF THE NAME OF ASSYRIA.—ILLUSTRATIONS OF SCRIPTURE.—STATE OF JUDÆA AND ASSYRIA COMPARED.—POLITICAL CONDITION OF THE EMPIRE.—ASSYRIAN COLONIES.—PROSPERITY OF THE COUNTRY.—RELIGION.—EXTENT OF NINEVEH.—ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE.—COMPARED WITH JEWISH.—PALACE OF KOUYUNJIK RESTORED.—PLATFORM AT NIMROUD RESTORED.—THE ASSYRIAN FORTIFIED INCLOSURES.—DESCRIPTION OF KOUYUNJIK.—CONCLUSION.

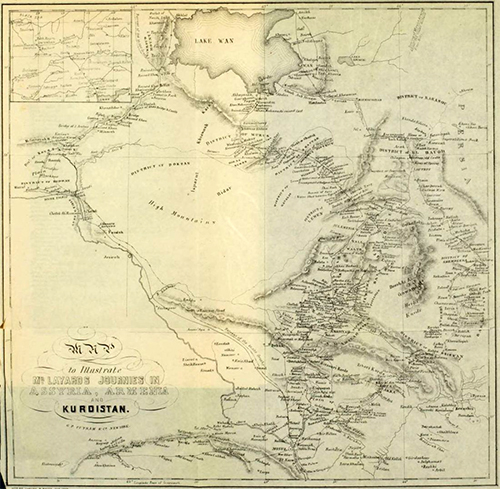

Although ten years have barely elapsed since the first discovery of ruins on the site of the great city of Nineveh, a mass of information, scarcely to be overrated for its importance and interest, has already been added to our previous knowledge of the early history and comparative geography of the East. When in 1849 I published the narrative of my first researches in Assyria, the numerous inscriptions recovered from the remains of the buried palaces were still almost a sealed book; for although an interpretation of some had been hazarded, it was rather upon mere conjecture than upon any well-established philological basis. I then, however, expressed my belief, that ere long their contents would be known with almost certainty, and that they would be found to furnish a history, previously almost unknown, of one of the earliest and most powerful empires of the ancient world. Since[Pg 492] that time the labors of English scholars, and especially of Col. Rawlinson and Dr. Hincks, and of M. de Saulcy, and other eminent investigators on the Continent, have nearly led to the fulfilment of those anticipations; and my present work would be incomplete were I not to give a general sketch of the results of their investigations, as well as of my own researches.

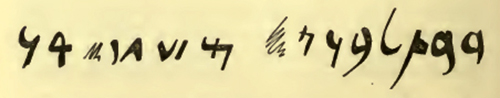

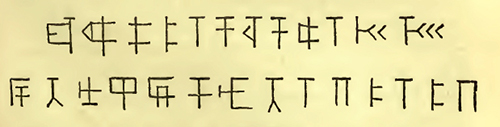

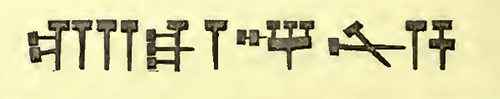

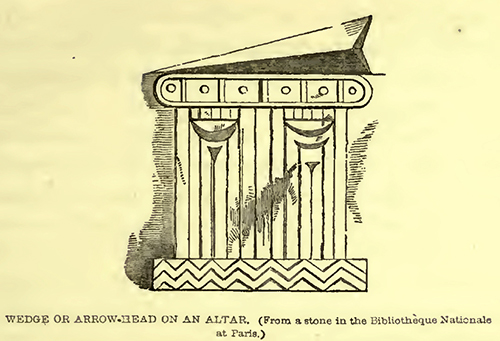

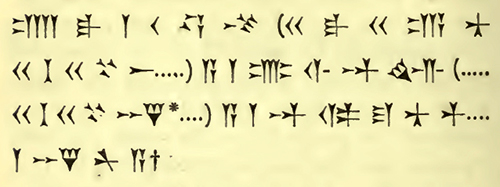

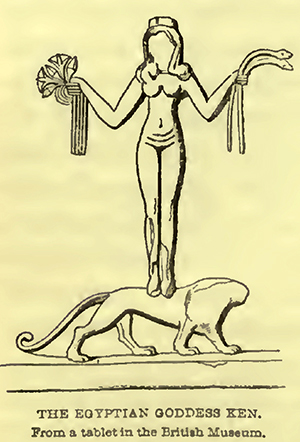

I will not detain the reader by any account of the various processes adopted in deciphering, and of the steps gradually made in the investigation; nor will I recapitulate the curious corroborative evidence which has led in many instances to the verification of the interpretations. Such details, philologically of the highest interest, and very creditable to the sagacity and learning of those pursuing this difficult inquiry, will be found in the several treatises published by the investigators themselves. The results, however, are still very incomplete. It is, indeed, a matter of astonishment that, considering the time which has elapsed since the discovery of the monuments, so much progress has been already made. But there is every prospect of our being able, ere long, to ascertain the general contents of almost every Assyrian record. The Babylonian column of the Bisutun inscription, that invaluable key to the various branches of cuneiform writing, has at length been published by Col. Rawlinson, and will enable others to carry on the investigation upon sure grounds.

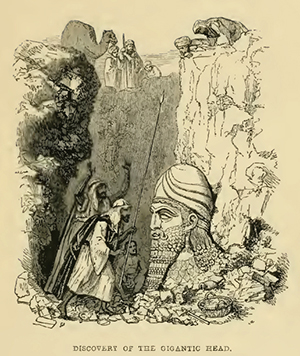

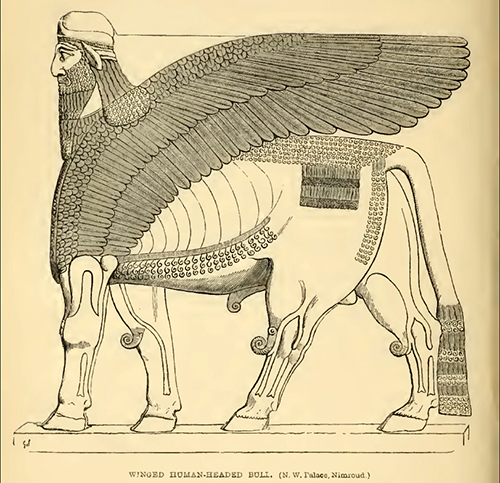

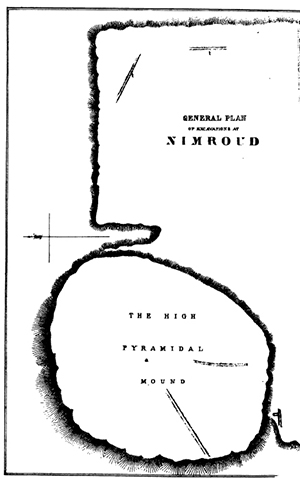

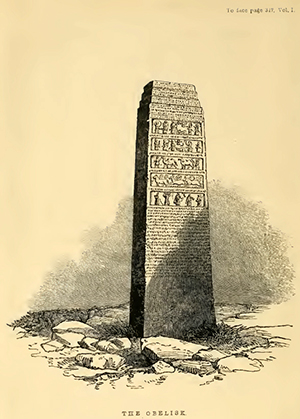

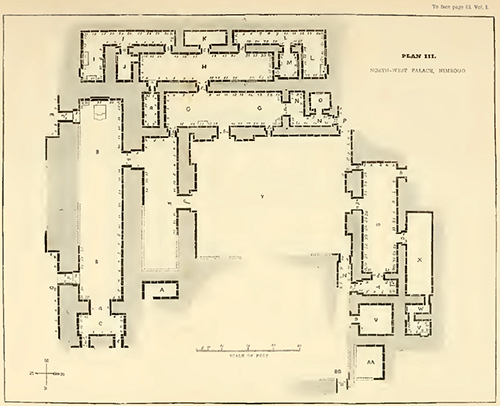

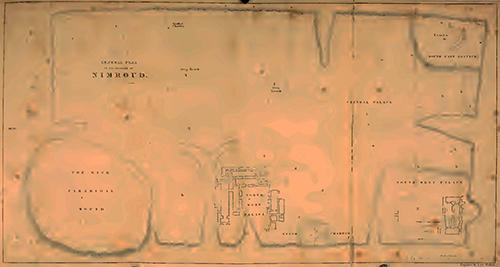

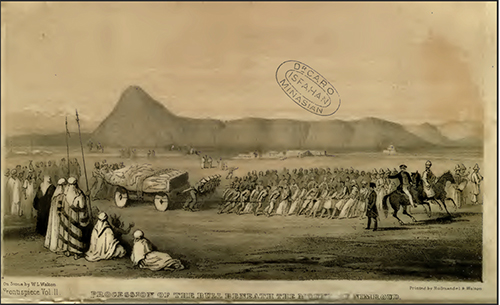

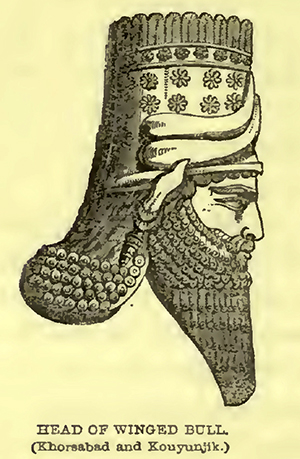

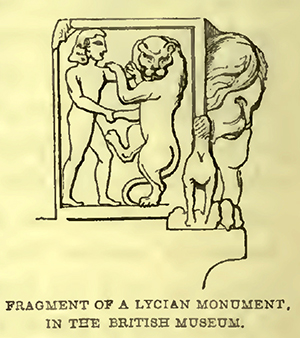

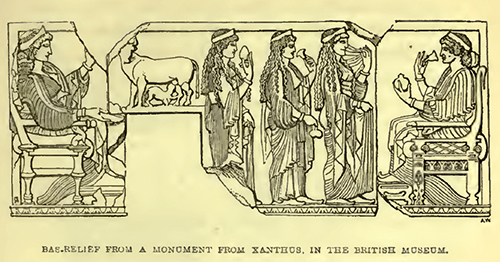

I will proceed, therefore, to give a slight sketch of the contents of the inscriptions as far as they have been examined. The earliest king of whose reign we have any detailed account was the builder of the north-west palace at Nimroud, the most ancient edifice hitherto discovered in Assyria. His records, however, with other inscriptions, furnish the names of five, if not seven, of his [Pg 493]predecessors, some of whom, there is reason to believe, erected palaces at Nineveh, and originally founded those which were only rebuilt by subsequent monarchs. It is consequently important to ascertain the period of the accession of this early Assyrian king, and we apparently have the means of fixing it with sufficient accuracy. His son, we know, built the centre palace at Nimroud, and raised the obelisk, now in the British Museum, inscribing upon it the principal events of his reign. He was a great conqueror, and subdued many distant nations. The names of the subject kings who paid him tribute are duly recorded on the obelisk, in some instances with sculptured representations of the various objects sent. Amongst those kings was one whose name reads “Jehu, the son of Khumri (Omri),” and who has been identified by Dr. Hincks and Col. Rawlinson with Jehu, king of Israel. This monarch was certainly not the son, although one of the successors of Omri, but the term “son of” appears to have been used throughout the East in those days, as it still is, to denote connection generally, either by descent or by succession. Thus we find in Scripture the same person called “the son of Nimshi,” and “the son of Jehoshaphat, the son of Nimshi.”[248] An identification connected with this word Khumri or Omri is one of the most interesting instances of corroborative evidence that can be adduced of the accuracy of the interpretations of the cuneiform character. It was observed that the name of a city resembling Samaria was connected, and that in inscriptions containing very different texts, with one reading Beth Khumri or Omri.[249] This fact was unexplained[Pg 494] until Col. Rawlinson perceived that the names were, in fact, applied to the same place, or one to the district, and the other to the town. Samaria having been built by Omri, nothing is more probable than that—in accordance with a common Eastern custom—it should have been called, after its founder, Beth Khumri, or the house of Omri. As a further proof of the identity of the Jehu mentioned on the obelisk with the king of Israel, Dr. Hincks, to whom we owe this important discovery, has found on the same monument the name of Hazael, whom Elijah was ordered by the Almighty to anoint king of Syria.[250]

Supposing, therefore, these names to be correctly identified,—and our Assyrian chronology for this period rests as yet, it must be admitted, almost entirely upon this supposition,—we can fix an approximate date for the reign of the obelisk king. Jehu ascended the throne about 885 b. c.; the accession of the Assyrian monarch must, consequently, be placed somewhere between that time and the commencement of the ninth century b. c., and that of his father in the latter part of the tenth.[251]

In his records the builder of the north-west palace mentions, amongst his predecessors, a king whose name is identical with the one from whom, according to the inscriptions at Bavian, were taken certain idols of Assyria 418 years before the first or second year of the reign of Sennacherib. According to Dr. Hincks, Sennacherib ascended the throne in 703 b. c. We have, therefore, 1121 b. c. for the date of the reign of this early king.

There are still two kings mentioned by name in the inscriptions from the north-west palace at Nimroud, as ancestors of its builder, who have not yet been [Pg 495]satisfactorily placed. It is probable that the earliest reigned somewhere about the middle of the twelfth century b. c. Colonel Rawlinson calls him the founder of Nineveh; but there is no proof whatever, as far as I am aware, in support of this conjecture. It is possible, however, that he may have been the first of a dynasty which extended the bounds of the Assyrian empire, and was founded, according to Herodotus, about five centuries before the Median invasion, or in the twelfth century b. c.; but there appears to be evidence to show that a city bearing the name of Nineveh stood on the banks of the Tigris long before that period.[252]

The second king, whose name is unplaced, appears to be mentioned in the inscriptions as the original founder of the north-west palace at Nimroud. According to the views just expressed, he must have reigned about the end of the twelfth century b. c.

The father and grandfather of the builder of the north-west palace are mentioned in nearly every inscription from that edifice. Their names, according to Colonel Rawlinson, are Adrammelech and Anáku-Merodach. They must have reigned in the middle of the tenth century b. c. We have no records of either of them.

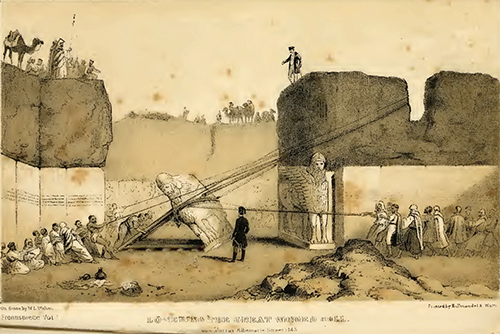

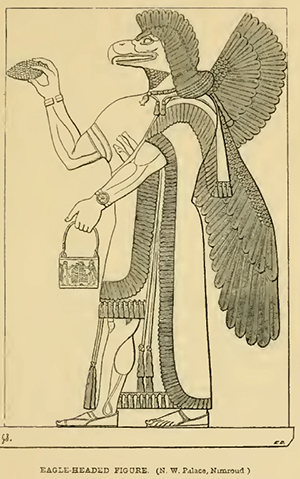

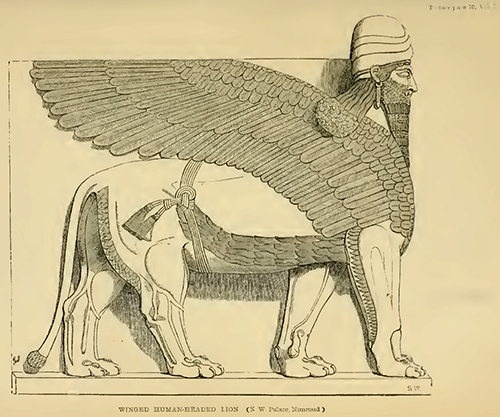

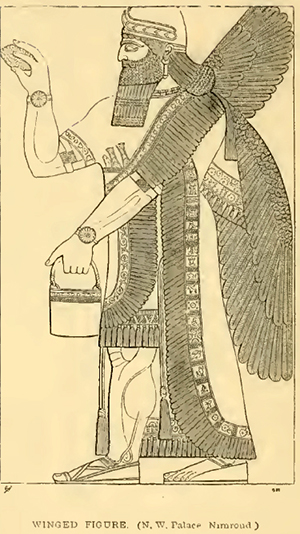

The first king of whom we have any connected historical chronicle was the builder of the well-known edifice at Nimroud from which were obtained the most perfect and interesting bas-reliefs brought to this country. In my former work I stated that Colonel Rawlinson believed his name to be Ninus, and had identified him with that ancient king, according to Greek history, the founder of the Assyrian empire. He has since given up this reading,[Pg 496] and has suggested that of Assardanbal, agreeing with the historic Sardanapalus. Dr. Hincks, however, assigning a different value to the middle character (the name being usually written with three), reads Ashurakhbal. It is certain that the first monogram stands both for the name of the country of Assyria and for that of its protecting deity. We might consequently assume, even were other proof wanting, that it should be read Assur or Ashur.

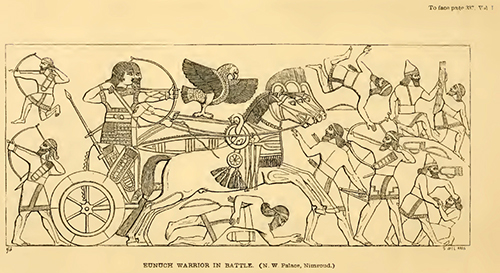

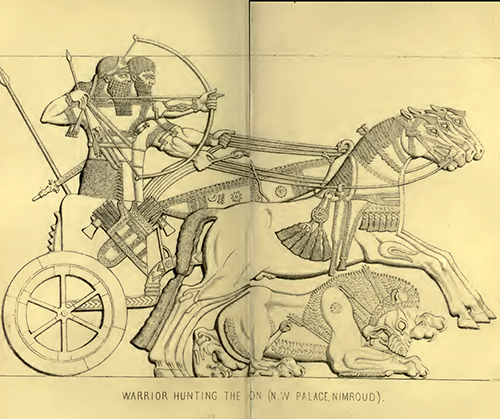

I have elsewhere given a description of the various great monumental records of this king, with extracts from their contents. He appears to have carried his arms to the west of Nineveh across Syria to the Mediterranean Sea, to the south into Chaldæa, probably beyond Babylon (the name of this city does not, however, as far as I am aware, occur in the inscriptions), and to the north into Asia Minor and Armenia.

Of his son, whose name Colonel Rawlinson reads Temenbar and Divanubara, and Dr. Hincks Divanubar, we have full and important historical annals, including the principal events of thirty-one years of his reign. They are engraved upon the black obelisk, and upon the backs of the bulls in the centre of the mound of Nimroud. This king, like his father, was a great conqueror. He waged war, either in person or by his generals, in Syria, Armenia, Babylonia, Chaldæa, Media, and Persia.

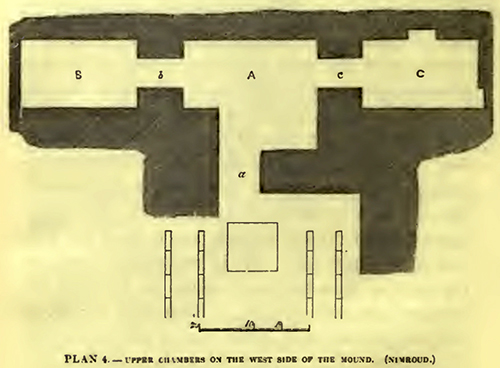

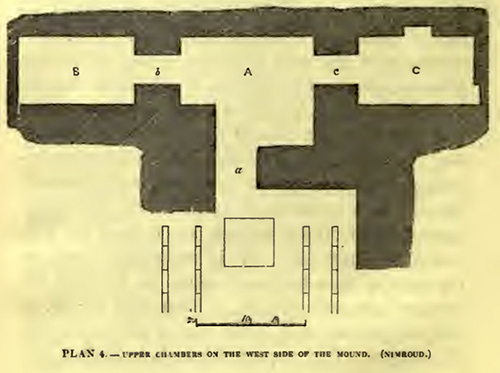

The two royal names next in order occur on the pavement slabs of the upper chambers, on the west face of the mound of Nimroud.[253] They may belong to the son and grandson, and immediate successors, of the obelisk king. The two names, however, have not been satisfactorily deciphered. Colonel Rawlinson reads them Shamas-Adar[Pg 497] and Adrammelech II.; Dr. Hincks only ventures to suggest Shamsiyav for the first.

On the Assyrian tablet from the tunnel of Negoub[254], are apparently two royal names, which may be placed next in order. They are merely mentioned as those of ancestors or predecessors of the king who caused the record to be engraved. Dr. Hincks reads them Baldasi and Ashurkish. As the inscription is much mutilated, some doubt may exist as to the correctness of its interpretation.

The next king of whom we have any actual records appears to have rebuilt or added to the palace in the centre of the mound of Nimroud. The edifice was destroyed by a subsequent monarch, who carried away its sculptures to decorate a palace of his own. All the remains found amongst its ruins, with the exception of the great bulls and the obelisk, belong to a king whose name occurs on a pavement-slab discovered in the south-west palace. The walls and chambers of this building were, it will be remembered, decorated with bas-reliefs brought from elsewhere. By comparing the inscriptions upon them, and upon a pavement-slab of the same period, with the sculptures in the ruins of the centre palace, we find that they all belong to the same king, and we are able to identify him through a most important discovery, for which we are also indebted to Dr. Hincks. In an inscription on a bas-relief representing part of a line of war-chariots, he has detected the name of Menahem, the king of Israel, amongst those of other monarchs paying tribute to the king of Assyria, in the eighth year of his reign.[255] This Assyrian king, must, consequently, have been either[Pg 498] the immediate predecessor of Pul, Pul himself, or Tiglath Pileser, the name on the pavement-slab not having yet been deciphered.[256]

The bas-reliefs adorning his palace, like those at Khorsabad, appear to have been accompanied by a complete series of his annals. Unfortunately only fragments of them remain. His first campaign seems to have been in Chaldæa, and during his reign he carried his arms into the remotest parts of Armenia, and across the Euphrates into Syria as far as Tyre and Sidon. There is a passage in one of his inscriptions still unpublished, which reads, “as far as the river Oukarish,” that might lead us to believe that his conquests were even extended to the central provinces of Asia and to the Oxus. His annals contain very ample lists of conquered towns and tribes. Amongst the former are Harran and Ur. He rebuilt many cities, and placed his subjects to dwell in them.

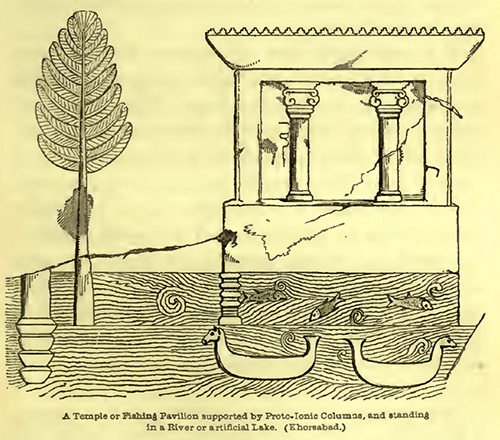

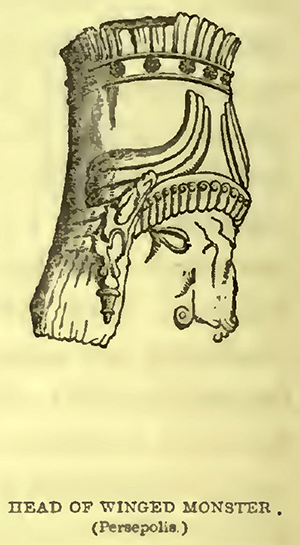

The next monarch, whose name is found on Assyrian monuments, was the builder of the palace of Khorsabad, now so well known from M. Botta’s excavations and the engravings of its sculptures published by the French government. His name, though read with slight variations by different interpreters, is admitted by all to be that of Sargon, the Assyrian king mentioned by Isaiah. The names of his father and grandfather are said to have been found on a clay tablet discovered at Kouyunjik, but they do not appear to have been monarchs of Assyria. The ruins of Khorsabad furnish us with the most detailed and ample annals of his reign. Unfortunately an inscription,[Pg 499] containing an account of a campaign against Samaria in his first or second year, has been almost entirely destroyed. But, in one still preserved, 27,280 Israelites are described as having been carried into captivity by him from Samaria and the several districts or provincial towns dependent upon that city. Sargon, like his predecessors, was a great warrior. He even extended his conquests beyond Syria to the islands of the Mediterranean Sea, and a tablet set up by him has been found in Cyprus. He warred also in Babylonia, Susiana, Armenia, and Media, and apparently received tribute from the kings of Egypt.

Colonel Rawlinson believed that the names “Tiglath Pileser” and “Shalmaneser,” were found on the monuments of Khorsabad as epithets of Sargon, and that they were applied in the Old Testament to the same king. He has now changed his opinion with regard to the first, and Dr. Hincks contends that the second is not a name of this king, but of his predecessor,—of whom, however, it must be observed, we have hitherto been unable to trace any mention on the monuments, unless, as that scholar suggests, he is alluded to in an inscription of Sargon from Khorsabad.

From the reign of Sargon we have a complete list of kings to the fall of the empire, or to a period not far distant from that event. He was succeeded by Sennacherib, whose annals have been given in a former part of this volume. His name was identified, as I have before stated, by Dr. Hincks, and this great discovery furnished the first satisfactory starting-point, from which the various events recorded in the inscriptions have been linked with Scripture history. Colonel Rawlinson places the accession of Sennacherib to the throne in 716, Dr. Hincks in 703, which appears to be more in accordance with the canon of Ptolemy. The events of his reign, as recorded[Pg 500] in the inscriptions on the walls of his palace, are mostly related or alluded to in sacred and profane history. I have already described his wars in Judæa, and have compared his own account with that contained in Holy Writ. His second campaign in Babylonia is mentioned in a fragment of Polyhistor, preserved by Eusebius, in which the name given to Sennacherib’s son, and the general history of the war appear to be nearly the same as those on the monuments. The fragment is highly interesting as corroborating the accuracy of the interpretation of the inscriptions. I was not aware of its existence when the translation given in the sixth chapter of this volume was printed. “After the reign of the brother of Sennacherib, Acises reigned over the Babylonians, and when he had governed for the space of thirty days he was slain by Merodach Baladan, who held the empire by force during six months; and he was slain and succeeded by a person named Elibus (Belib). But in the third year of his (Elibus) reign Sennacherib, king of the Assyrians, levied an army against the Babylonians; and in a battle, in which they were engaged, routed and took him prisoner with his adherents, and commanded them to be carried into the land of the Assyrians. Having taken upon himself the government of the Babylonians, he appointed his son, Asordanius, their king, and he himself retired again into Assyria.” This son, however, was not Essarhaddon, his successor on the throne of Assyria. The two names are distinguished by a distinct orthography in the cuneiform inscriptions. Sennacherib raised monuments and caused tablets recording his victories to be carved in many countries which he visited and subdued. His image and inscriptions at the mouth of the Nahr-el-Kelb in Syria are well known. During my journey to Europe I found one of his tablets near the village of Hasana (or Hasan[Pg 501] Agha), chiefly remarkable from being at the foot of Gebel Judi, the mountain upon which, according to a widespread Eastern tradition, the ark of Noah rested after the deluge.[257]

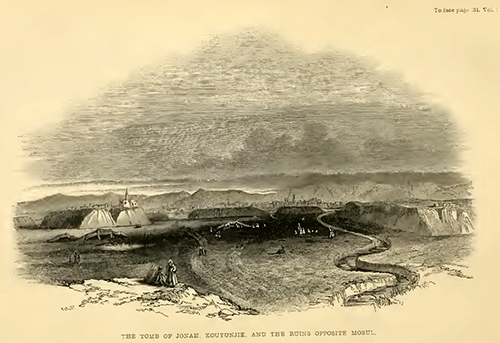

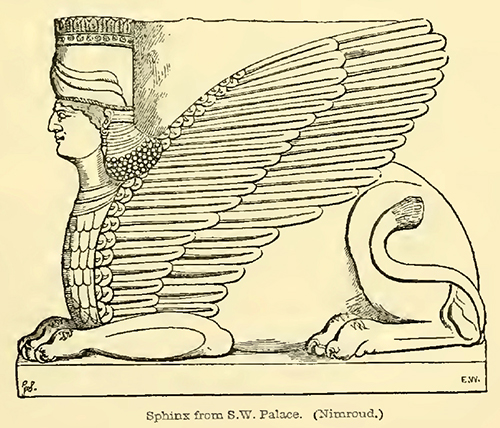

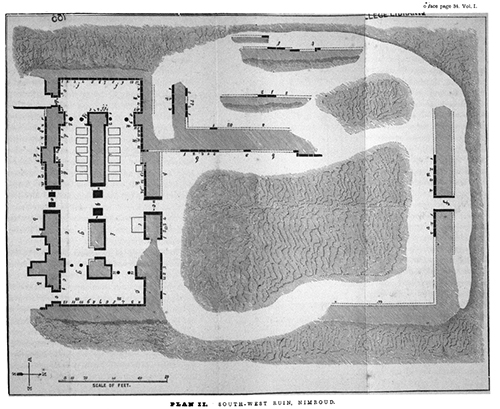

Essarhaddon, his son, was his successor, as we know from the Bible. He built the south-west palace at Nimroud, and an edifice whose ruins are now covered by the mound of the tomb of Jonah opposite Mosul. Like his father he was a great warrior, and he styles himself in his inscriptions “King of Egypt, conqueror of Æthiopia.” It was probably this king who carried Manasseh, king of Jerusalem, captive to Babylon.[258]

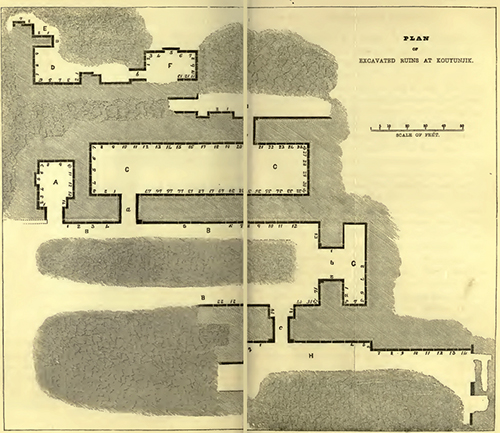

The name of the son and successor of Essarhaddon was the same as that of the builder of the north-west palace at Nimroud. His father had erected a dwelling for him in the suburbs or on the outskirts of Nineveh. His principal campaign appears to have been in Susiana or Elam. As the great number of the inscribed tablets found in the ruins of the palace of Sennacherib, at Kouyunjik, are of his time, many of them bearing his name, we may hope to obtain some record of the principal events of his reign.

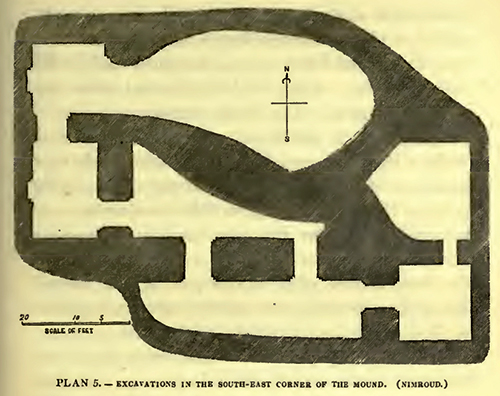

His son built the south-east palace on the mound of Nimroud, probably over the remains of an earlier edifice. Bricks from its ruins give his name, which has not yet been deciphered, and those of his father and grandfather. We know nothing of his history from cotemporaneous records. He was one of the last, if not the last, king of the second dynasty; and may, indeed, as I have already suggested, have been that monarch, Sardanapalus, or Saracus, who was conquered by the combined armies of the Medes and Babylonians under Cyaxares in b. c. 606, and[Pg 502] who made of his palace, his wealth, and his wives one great funeral pile.[259]

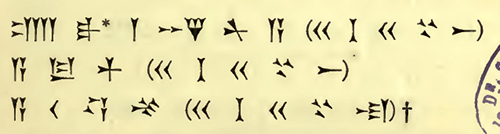

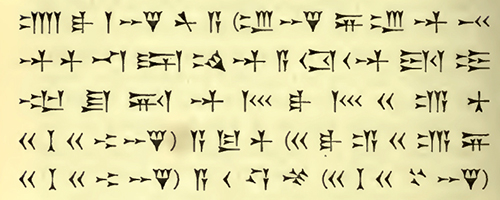

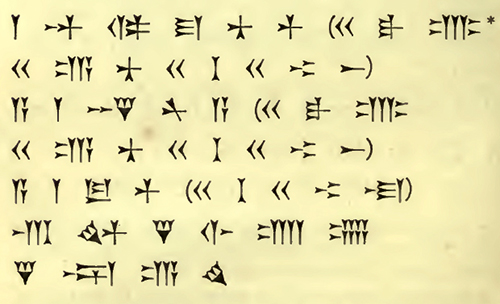

For convenience of reference I give a table of the royal names, according to the versions of Dr. Hincks and Col. Rawlinson, the principal monuments on which they are found, and the approximate date of the reigns of the several kings. In a second table will be found the most important proper and geographical names in the Assyrian inscriptions which have been identified with those in the Bible. A third table contains the names of the thirteen great gods of Assyria, according to the version of Dr. Hincks.

TABLE I.—Names of Assyrian Kings in the Inscriptions from Nineveh.

Conjectural reading. / Where found. / Approximate Date of reign.

1. Derceto (R[260])

Divanurish (H) Pavement Slab, (B. M. Series, p. 70, l. 25) 1250 B. C.

2. Divanukha (R) Standard Inscription, Nimroud, &c. 1200 B. C.

3. Anakbar-beth-hira (R)

Shimish-bal-Bithkhira (H) Slabs from Temples in North of Mound of

Nimroud; Bavian tablets, &c. 1130 B. C.

Mardokempad (?) (R)

Mesessimordacus (?) (R) A cylinder from Shereef-Khan

[Pg 503]

4. Adrammelech I. (R) Standard Inscription, Bricks, &c., from N. W.

Palace, Nimroud 1000 B. C.

5. Anaku Merodak (R)

Shimish Bar (H)

(Son of preceding) Idem 960 B. C.

6. Sardanapalus I. (R)

Ashurakhbal (H)

(Son of preceding) Standard Inscription, Bricks, &c., from N. W.

Palace, Nimroud, Abou Maria, &c., &c. 930 B. C.

7. Divanubara (R)

Divanubar (H)

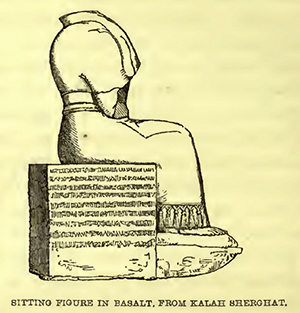

(Son of preceding) Centre Palace, Nimroud; Obelisk; Bricks;

Kalah-Sherghat; Baashiekha 900 B. C.

8. Shamas Adar (R)

Shamsiyav (H) Pavement Slab, Upper Chambers, Nimroud 870 B. C.

9. Adrammelech II. (R) Idem 840 B. C.

10. Baldasi (?) (H) Slab from the tunnel of Negoub

11. Ashurkish (?) (H) Idem

12. ? Pul or Tiglath-Pileser Pavement Slab, and Slabs built into the S. W.

Palace, Nimroud 750 B. C.

13. Sargon Khorsabad; Nimroud; Karamless, &c., &c. 722 B. C.

14. Sennacherib

(Son of preceding) Kouyunjik, &c. 703 B. C.

15. Essarhaddon

(Son of preceding) S. W. Palace, Nimroud; Nebbi Yunus;

Shereef-Khan 690 B. C.?

16. Sardanapalus III. (R)

Ashurakhbal (H)

(Son of preceding) Kouyunjik; Shereef-Khan

17. (Son of preceding) S. E. Edifice, Nimroud

18. Shamishakhadon (?) (H) Black Stone, in possession of Lord Aberdeen[/quoteTABLE II.—Names of Kings, Countries, Cities, &c., mentioned in the Old Testament, which occur in the A Inscriptions.

Jehu,

Omri,

Menahem,

Hezekiah,

Hazael,

Merodach Baladan,

Pharoah,

Sargon,

Sennacherib,

Essarhaddon,

Dagon,

Nebo,

Judæa,

Jerusalem,

Samaria,

Ashdod,

Lachish,

Damascus,

Hamath, Hittites (the),

Tyre,

Sidon,

Gaza,

Ekron,

Askelon,

Arvad,

Gubal (the people of),

Lebanon,

Egypt,

Euphrates,

Carchemish,

Hebar or Chebar (river),

Harran,

Ur,

Gozan (the people of),

Mesopotamia,

Children of Eden,

Tigris, Nineveh,

Babylon,

Elam,

Shushan,

Media,

Persia,

Yavan,

Ararat,

Hagarenes,

Nabathæans,

Aramæans,

Chaldæans,

Meshek,

Tubal,

Assyria,

Assyrians,

Pethor,

Telassar.

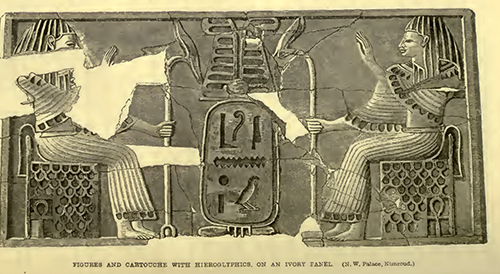

TABLE III.—Names of Thirteen Great Gods of Assyria, as they occur on the upright tablet of the King, discovered at Nimroud.

1. Asshur, the King of the Circle of the Great Gods.

2. Anu, the Lord of the Mountains, or of Foreign Countries.

3.(?) [Not yet deciphered.]

4. San.

5. Merodach (? Mars).

6. Yav (? Jupiter).

7. Bar.

8. Nebo (? Mercury).

9. (?) Mylit (or Gula), called the Consort of Bel and the Mother of the Great Gods (? Venus).

10. (?) Dagon.

11. Bel (? Saturn) Father of the Gods.

12. Shamash (the Sun).

13. Ishtar (the Moon).

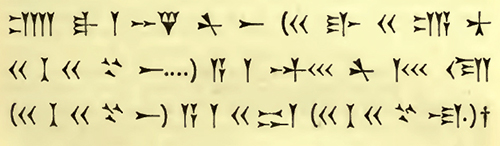

[Pg 505]Although no mention appears to be made in the Assyrian inscriptions of kings who reigned before the twelfth century b. c., this is by no means a proof that the empire, and its capital Nineveh, did not exist long before that time. I cannot agree with those who would limit the foundation of both to that period. The supposition seems to me quite at variance with the testimony of sacred and profane history. The existence of the name of Nineveh on monuments of the eighteenth Egyptian dynasty is still considered almost certain by Egyptian scholars. I have in my former work quoted an instance of it on a tablet of the time of Thothmes III., or of the beginning of the fourteenth century b. c.[261] Mr. Birch has since pointed out to me three interesting cartouches copied by Dr. Lepsius in Egypt, which completely remove any doubt as to the name of Assyria having been also known as early as the eighteenth dynasty. They occur at the foot of one of the columns of Soleb, and are of the age of Amenophis III., or about the middle of the fourteenth century before Christ. The three figures, with their arms bound behind, represent Asiatic captives, as is proved by their peculiar features and head-dress, a knotted fillet round the temples, corresponding with that seen in the Nineveh sculptures. Each cartouche contains the name of the country from which the prisoner was brought. The first is Patana, or Padan-Aram; the second is written A-su-ru, or Assyria; and the third, Ka-ru-ka-mishi, Carchemish. On another column are Saenkar (? Shinar or Sinjar); Naharaina, or Mesopotamia; and the Khita, or Hittites. The mention in succession of these Asiatic nations, contiguous one to the other, proves the correctness of the reading of the word Assyria,[Pg 506] which might have been doubted had the name of that country stood alone.

Mr. Birch has detected a still earlier notice of Assyria in the statistical tablet of Karnak. The king of that country is there stated to have sent to Thothmes III., in his fortieth year, a tribute of fifty pounds nine ounces of some article called chesbit, supposed to be a stone for coloring blue. It would appear, therefore, that in the fifteenth century a kingdom, known by the name of Assyria, with Nineveh for its capital, had been established on the borders of the Tigris. Supposing the date now assigned by Col. Rawlinson to the monuments at Nimroud to be correct, no sculptures or relics have yet been found which we can safely attribute to that period; future researches and a more complete examination of the ancient sites may, however, hereafter lead to the discovery of earlier remains.

As I have thus given a general sketch of the contents of the inscriptions, it may not be out of place to make a few observations upon the nature of the Assyrian records, and their importance to the study of Scripture and profane history. In the first place, the care with which the events of each king’s reign were chronicled is worthy of remark. They were usually written in the form of regular annals, and in some cases, as on the great monoliths at Nimroud, the royal progress during a campaign appears to have been described almost day by day. We are thus furnished with an interesting illustration of the historical books of the Jews. There is, however, this marked difference between them, that whilst the Assyrian records are nothing but a dry narrative, or rather register, of military campaigns, spoliations, and cruelties, events of little importance but to those immediately concerned in them, the historical books of the[Pg 507] Old Testament, apart from the deeds of war and blood which they chronicle, contain the most interesting of private episodes, and the most sublime of moral lessons. It need scarcely be added, that this distinction is precisely what we might have expected to find between them, and that the Christian will not fail to give to it a due weight.

The monuments of Nineveh, as well as the testimony of history, tend to prove that the Assyrian monarch was a thorough Eastern despot, unchecked by popular opinion, and having complete power over the lives and property of his subjects—rather adored as a god than feared as a man, and yet himself claiming that authority and general obedience in virtue of his reverence for the national deities and the national religion. It was only when the gods themselves seemed to interpose that any check was placed upon the royal pride and lust; and it is probable that when Jonah entered Nineveh crying to the people to repent, the king, believing him to be a special minister from the supreme deity of the nation, “arose from his throne, and laid his robe from him, and covered him with sackcloth, and sat in ashes.”[262] The Hebrew state, on the contrary, was, to a certain extent, a limited monarchy. The Jewish kings were amenable to, and even guided by, the opinion of their subjects. The prophets boldly upbraided and threatened them; their warnings and menaces were usually received with respect and fear. “Good is the word of the Lord which thou hast spoken,” exclaimed[Pg 508] Hezekiah to Isaiah, when the prophet reproved him for his pride, and foretold the captivity of his sons and the destruction of his kingdom;[263] a prophecy which none would have dared utter in the presence of the Assyrian king, except, as it would appear by the story of Jonah, he were a stranger. It can scarcely, therefore, be expected that any history other than bare chronicles of the victories and triumphs of the kings, omitting all allusion to their reverses and defeats, could be found in Assyria, even were portable rolls or books still to exist, as in Egypt, beneath the ruins.

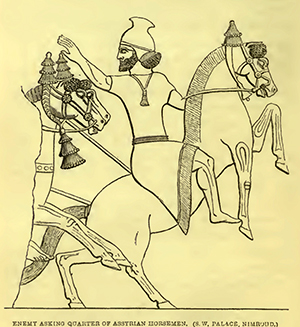

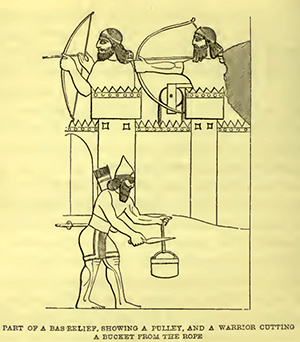

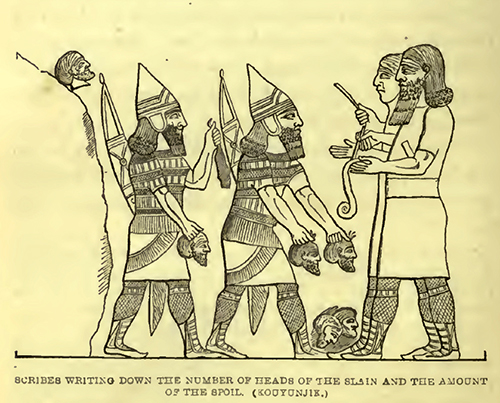

It is remarkable that the Assyrian records should, on the whole, be so free from the exaggerated forms of expression, and the magniloquent royal titles, which are found in Egyptian documents of the same nature, and even in those of modern Eastern sovereigns. I have already pointed out the internal evidence of their truthfulness so far as they go. We are further led to place confidence in the statements contained in the inscriptions by the very minuteness with which they even give the amount of the spoil; the two registrars, “the scribes of the host,” as they are called in the Bible,[264] being seen in almost every bas-relief, writing down the various objects brought to them by the victorious warriors,—the heads of the slain, the prisoners, the cattle, the sheep,[265] the furniture, and the vessels of metal.

[Pg 509]The next reflection arising from an examination of the Assyrian records relates to the political condition and constitution of the empire, which appear to have been of a very peculiar nature. The king, we may infer, exercised but little direct authority beyond the immediate districts around Nineveh. The Assyrian dominions, as far as we can yet learn from the inscriptions, did not extend much further than the central provinces of Asia Minor and Armenia to the north, not reaching to the Black Sea, though probably to the Caspian. To the east they included the western provinces of Persia; to the south, Susiana, Babylonia, and the northern part of Arabia. To the west the Assyrians may have penetrated into Lycia, and perhaps Lydia; and Syria was considered within the territories of the great king; Egypt and Meroe (Æthiopia) were the farthest limits reached by the Assyrian armies. According to Greek history, however, a much greater extent must be assigned to Assyrian influence, if not to the actual Assyrian empire, and we may hereafter find that such was in fact the case. I am here merely referring to the evidence afforded by actual records as far as they have been deciphered.

The empire appears to have been at all times a kind of confederation formed by many tributary states, whose kings were so far independent, that they were only bound to furnish troops to the supreme lord in time of war, and to pay him yearly a certain tribute. Hence we find successive Assyrian kings fighting with exactly the same nations and tribes, some of which were scarcely more than four or five days’ march from the gates of Nineveh.

The Jewish tribes, as it had long been suspected by biblical scholars, can now be proved to have held their dependent position upon the Assyrian king, from a very early period, indeed, long before the time inferred by any[Pg 510] passage in Scripture. Whenever an expedition against the kings of Judah or Israel is mentioned in the Assyrian records, it is stated to have been undertaken on the ground that they had not paid their customary tribute.[266]

The political state of the Jewish kingdom under Solomon appears to have been very nearly the same as that of the Assyrian empire. The inscriptions in this instance again furnish us with an interesting illustration of the Bible. The scriptural account of the power of the Hebrew king resembles, almost word for word, some of the paragraphs in the great inscriptions at Nimroud. “Solomon reigned over the kingdoms from the river unto the land of the Philistines, and unto the border of Egypt: they brought presents, and served Solomon all the days of his life.... He had dominion over all the region on this side the river, from Tipsah even unto the Azzah, over all the kings on this side the river.”[267]

In the custom, frequently alluded to in the inscriptions, of removing the inhabitants of conquered cities and districts to distant parts of the empire, and of replacing them by colonists from Nineveh or from other subdued countries, we have another interesting illustration of Scripture history. It has generally been inferred that there was but one carrying away, or at the most two, of the people of Samaria, although three, at least, appear to be distinctly alluded to in the Bible; the first, by Pul;[268][Pg 511] the second, by Tiglath-Pileser[269]; the third, by Shalmaneser.[270] It was not until the time of the last king that Samaria was destroyed as an independent kingdom. On former occasions only the inhabitants of the surrounding towns and villages seem to have been taken as captives. Such we find to have been the case with many other nations who were subdued or punished for rebellion by the Assyrians. The conquerors, too, as we also learn from the inscriptions, established the worship of their own gods in the conquered cities, raising altars and temples, and appointing priests for their service. So after the fall of Samaria, the strangers who were placed in its cities, “made gods of their own and put them in the houses of the high places which the Samaritans had made.”[271]

The vast number of families thus sent to dwell in distant countries, must have wrought great changes in the physical condition, language, and religion of the people with which they were intermixed. When the Assyrian records are with more certainty interpreted, we may, perhaps, be able to explain many of the anomalies of ancient Eastern philology and comparative geography.

We further gather from the records of the campaigns of the Assyrian kings, that the country, both in Mesopotamia and to the west of the Euphrates, now included in the general term of “the Desert,” was at that remote period, teeming with a dense population both sedentary and nomade; that cities, towns, and villages arose on all sides; and that, consequently, the soil brought forth produce for the support of this great congregation of human beings. All those settlements depended almost exclusively upon artificial irrigation. Hence the dry beds of enormous[Pg 512] canals and countless watercourses, which are spread like a network over the face of the country. Even the traveller, accustomed to the triumphs of modern science and civilization, gazes with wonder and awe upon these gigantic works, and reflects with admiration upon the industry, the skill, and the power of those who made them. And may not the waters be again turned into the empty channels, and may not life be again spread over those parched and arid wastes? Upon them no other curse has alighted than that of a false religion and a listless race.