PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION The princely and truly patriotic liberality of His Highness the Maharajah[1] of Vijayanagara has enabled me to take up once more in the evening of my life that work which has occupied me during my youth and during my advancing years.I had hardly left the University when the conviction forced itself upon me that,

without a knowledge of the Veda, all our study of Sanskrit literature would lack its solid foundation. I therefore determined to devote my life to an edition of the Rig-veda with its Sanskrit commentary by Sayanakarya, a task which at that time seemed certainly far beyond my powers, but which nevertheless, with the assistance of many kind friends, I have been allowed to bring to its completion within the space of twenty-four years, 1849-1873. Why the completion of this work should have required so many years, no one acquainted with its difficulties and with the difficulties of a scholar's struggles in early life, will be at a loss to understand. I myself have often grudged the time which I had to devote to this self-imposed task. But I felt convinced that the work had to be done, I was encouraged by all the most eminent Sanskrit scholars of the time to persevere in it, and, I may say it now without conceit, I have been fully rewarded by the results which it has produced. Not only have the Vedic studies in Europe during the last forty years opened before our eyes a completely new period in the history of language, mythology, and religion, but among scholars in India also a new interest in the ancient literature of their country has sprung up, and much good work has been done by them, if not exactly in the spirit of European scholarship, yet with some most important practical results to themselves and their fellow-countrymen.

It is this newly awakened and constantly spreading interest in Vedic literature in India which has necessitated a new edition of the Rig-veda and its commentary by Sayanakarya. Whatever the opinion of European scholars may be as to the real value of Sayana's commentary, native students naturally turn first to a native commentary, before venturing on an independent critical study of their ancient sacred texts. During the last ten years constant applications arrived from India for copies of my edition of the Rig-veda, but the first, the second, soon also the third and fourth volumes were sold out, and the six volumes together had to be bought at a price double of that at which they had been originally published.

Overwhelmed as I was with other and to me far more attractive work, I felt no desire whatever to undertake a new edition of these enormous volumes. But when I was told again and again by my Indian friends that the scarcity of copies seriously interfered

in many parts of India with the newly re-awakened study of the Veda, I felt that I ought not to shrink from a work to which they evidently thought that I was in honour pledged. I therefore expressed to the Secretary of State fur India my readiness to undertake a revised edition, giving my time and labour gratuitously, provided that the expense of printing were undertaken by the Indian Government. I did not imagine that in making such an offer I could be supposed to be asking for a favour. Grateful as I have always felt for the enlightened liberality of the Court of the Directors of the late East-India Company, I may be permitted to point out that they and their successors have received a very fair return for the outlay on the first edition, in the shape of 500 copies, representing a value of £7,500, which were either distributed by them as valued presents, or actually sold in the market.

The Members of the India Council, however, took a different view from that taken by their predecessors, the Directors of the old East-India Company. While the Directorls on the advice of the greatest Sanskrit scholar of the time, Professor H. H. Wilson, their illustrious Librarian, declared that

'the publication of so important and interesting a work as the Editio princeps of the Rig-veda, was in a peculiar manner deserving of the patronage of the East-India Company, connected as it is with the early religion, history, and language of the great body of their Indian subjects,' the literary Committee of the India Council, acting on somewhat different advice, declined my offer of publishing a new edition of the Rig-veda, though a strong desire for it had been expressed by scholars both in India and Europe, and though my gratuitous services were placed at their disposal.

No one felt more relieved by this decision than myself, but others took a different view, and in India particularly the motives, real or imaginary, of this refusal were canvassed very freely. Being asked by several of my Indian correspondents whether I would allow my edition to be reprinted in India, I replied that I should gladly give my permission to a duly qualified native scholar, but that it would be a pity to simply reprint it, without incorporating the numerous connections and additions which I had made in the course of the last thirty years, partly by availing myself of the criticisms of European and native scholars, partly by a collation of new and important MSS. which were not accessible to me when I published the original edition.

After several more or less feasible plans had been suggested, I received a letter from His Highness the Maharajah of Vijayanagara, offering to defray the whole expense of a new edition, if I were still willing to undertake the labour of revising the text. 'Your study of the literature of India and its people,' the Maharajah wrote, 'has decidedly established a great claim on all Hindus to help you to the best of their abilities in any undertaking, much more in one of such literary and religious importance to ourselves.'

After this generous offer from one of the most enlightened and distinguished Princes of India -- the Maharajah was a Member of the Legislative Council of the Governor of Madras during the Governorship of Sir Mountstuart E. Grant Duff, and is now a Member of the Viceregal Legislative Council -- I could hesitate no longer.

I gave up some other work which I had contemplated, and was fortunate enough to secure the assistance of an excellent young Sanskrit scholar, Dr. Winternitz, a pupil of Professor Buhler of Vienna. After the necessary preparations had been completed, we began our work in the spring of 1888.

In order not to delay the actual printing,

I began the new edition with the second Mandala. The first Mandala was the one which required the most careful critical revision. I was myself a novice in this field of scholarship, when I published it in 1849. Many of the books quoted by Sayana and supposed to be generally known to his readers, were accessible at that time in MSS. only, but have since been published, and had therefore to be carefully re-examined. New MSS. also of Sayana's commentary, and some of them far more valuable than those which I possessed forty years ago, have been lent me for this new edition.

In the main, this new edition is an exact reproduction of the original edition, which, therefore, for all practical purposes, will not be superseded by the new one. But there are in every text difficult or doubtful readings, of interest to the scholar only, and these have all been carefully reconsidered with the help of the new material now at our disposal. Dr. Winternitz has, I believe, most conscientiously verified all the quotations occurring in the first edition, and has added many references to texts published since. References to the Varttikas have now been given according to Professor Kielhorn's edition of the Mahabhashya. Bohtlingk's new edition of Panini's Sutras has proved very useful, likewise the new edition of the Nirukta by Pandit Satyavrata Samasrami. Dr. Winternitz, as well as another young and very promising scholar, Mr. Strong, has collated for me and recollated several MSS., has removed old misprints, and has done all that could be done to guard against the creeping in of new ones. He has also been of great help to me in determining the adoption of new readings resting on the authority of new MSS., or recommended by other scholars who have devoted their attention to the study of Sayana's commentary. In all this work he has proved himself a pupil worthy of his teacher, Professor Buhler, conscientious, accurate, yet not pedantic, and has earned the gratitude of all scholars who in future will use this new edition in pursuit of their Vedic studies.The MSS. of Sayana remain divided into three families, as I described them in my various prefaces to the first edition. The three presuppose one common source, a Codex archetypus, though we are not always able to restore its text with perfect certainty. There is no reason, however, why this Codex archetypus should not still be recovered, but all my inquiries, even in the monastery of Sringeri, of which Sayana was once an inmate, have hitherto been in vain.

For this new edition several MSS. have been collated, or recollated, or consulted for all difficult passages.

Two Grantha MSS. (G) belonging to the Royal Asiatic Society, the one containing hymns 1 to 19, the other hymns 122 to 165, of the first Mandala, have been collated, as well as a Tulu MS. (T), belonging to the same Society, which extends from I. 75 to the end of the first Ashtaka. It has been impossible, hitherto, to gain access to any other Grantha or Tulu MSS.

My own MS. (Ca), which had not reached me when I began to publish my first edition, has been collated for Ashtaka I by Mr. Strong. In all cases where various readings from Ca are given, they have been verified by Dr. Winternitz.The Berlin MS. (A 3) of the first Ashtaka (see above, pp. vii, xix) has been collated from the beginning to I. 76. For the rest of the Ashtaka it has always been referred to for critical passages.

I have to express my sincere thanks to Dr. Wilmanns, the Chief Librarian of the Royal Library of Berlin, for having allowed me the use of this valuable MS. at Oxford, more particularly at a time when it had been resolved not to lend any MSS. to members of our University.The MSS. A 2 and B 1 have likewise been consulted whenever they are quoted in the Varietas Lectionis.

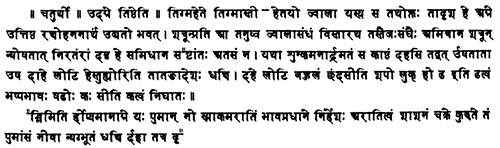

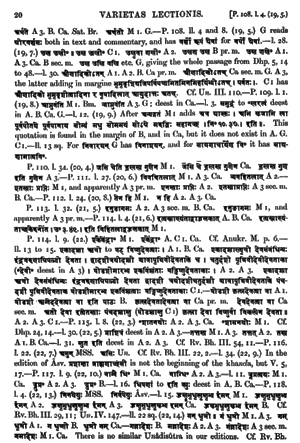

M I, for the first Ashtaka, represents the MSS. on which the Editio princeps was based. Since A 2 and B are included in these MSS., they have been mentioned only in such cases where they differ from M 1. In all the cases, therefore, where no reading of A 2 or B is mentioned, it must be understood that they agree with M 1. Thus, e. g. p.1. l. 25. [x] M 1. A 3. Ca. [x] G, means that A 2 and B also have [x]. Or, p. I. l. 20. [x] M 1. A 3. Ca. [x] G. B,' shows that A 2 also reads [x]. And again, 'p. 16. l. 9. [x] A 2. A 3. G. [x] M 1. Ca,' means that B also reads "[x], etc.

The chief MSS. used for the first edition were--

A 2 and A 1. Of A 3 only short notes and extracts had been made.

B1 and B 2.

C 1. C 1b. C 2. C 3. C 4. C 5. C 6.

I was not able to print the Varietas Lectionis for the first Ashtaka, and as I used the copy which contained my collations as manuscript for printing, I found that I only possessed the collations of A 1 from the beginning to hymn 33, 5, and those of C 1 from the beginning to hymn 61. These have been used for the new edition, but as in the mean time I had received several important MSS., I did not think it necessary to have A 1 and C 1 recollated. Their place has been taken by A 2. A 3. B 1. Ca. G and T, and the readings of all these MSS. will always be found, wherever the text seemed incorrect or doubtful.

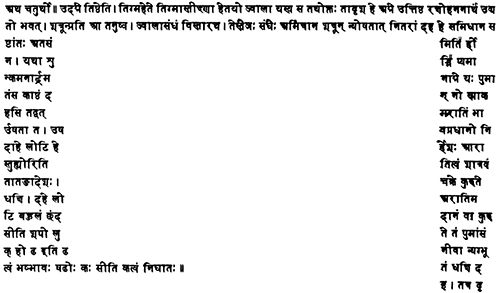

Mudgala's abridged commentary mentioned in Mr. Fitz-Edward Hall's letter (see above, p, xlviii) has been used for this new edition. But though it proved very useful for Mandalas II to VI, it was of very little use for the first Mandala. While it belongs to the B class in its later portions, it is in the first Mandala a very insignificant representative of the C class. In the few cases where it proved of any use, its readings have been given in the Varietas Lectionis.The MS. B m consists really of four bundles. The one containing the first Ashtaka, the other two the second and third Ashtakas, and the last a fragment containing Adhyayas 5 to 8 of the fourth Ashtaka. The MS. containing the first Ashtaka has a short introduction in which Mudgala is mentioned as the author of the abridged commentary: [x] etc. (see above, p. xlviii). In the MSS. containing Ashtakas II, III, and fragments of IV, Madgala's name is not mentioned. The colophons simply say:

[x].

It is, therefore, doubtful whether Ashtakas II to IV are Mudgala's work, or the work of the same author to whom the abridgement of Sayana's commentary in large portions of the B MSS. is due. Ashtakas II and III are of the same size as Ashtaka I, and written in a similar style of handwriting. The fragments of the fourth Ashtaka are of a different size, and written by a different hand. Ashtakas I to III therefore have most likely been avridged by Mudgala himself.

In the second volume, B m has been quoted much more frequently than in volume i. In all important cases it has been consulted, and its various readings have at first been entered separately. Afterwards they have only been quoted in cases where B m differs from V, with which it is intimately connected. How close this connection is, may be seen from passages such as IV. 4. 5;11, 12; 17, 4; 17, 16, and many others mentioned in the Varietas Lectionis. In many cases B m has the correct reading, while all the other MSS. are at fault, e. g. IV. 3 1, 15.

In several cases, emendations made by me in the first edition by mere conjecture, have been confirmed by B m. Though Bm belongs to the B class, it is not directly derived from B 1. It omits throughout all grammatical explanations, all quotations from the Nighantu, the Nirukta, the Anukramani, and from the Sruti in general, all Viniyogas also, and all optional renderings. It supplies, however, the names of the poets, the metres, and the deities. From II. 33, I to II. 34, 4, the commentary in B is nearly identical with the abridged text of B m, which, however, is sometimes shorter than B. In the third Ashtaka B m agrees occasionally with Ca, while B follows A, as in III. 7, 4; 49, 2 ; 51. 3. 10. This may be due to later corrections.

From the beginning of Ashtaka IV to the beginning of the fifth Adhyaya B m is lost. B offers here an abridged text, and where B m begins again, it agrees with B, but is rather more correct, e. g. VI. 6, 5. 6. From VI. 62, B 1 and B 2 begin to differ, the former giving the complete, the latter an abridged text of the commentary. In the abridged portion of B, extending from V. 8, 2 to VI. 42, 2, B, Bm, and Ca go together, where they differ from A, while afterwards B and A often go together, where they differ from Co. and Bm.

A considerable number of passages which do not occur in the chief MSS. (A. B. Ca) have been printed in the text of M 1, because, as stated in the preface to vol. i (see above, p. xxiii), they seemed to be useful. Many of these passages, however, have now been relegated to the Varietas Lectionis, namely, all those which clearly show their later character. Others which might have been written by Sayana, have been left in the text, but a note has been made in the Varietas Lectionis.The MSS. G and T are the most important of the new MSS. available for volume i. But they do not exist for the whole volume.

Whish Coll. No. 13 (G) contains Sayana's Introduction and the first 19 hymns. It is written in Grantha characters.

Whish Coll. No. 2 (T) contains the hymns I. 75 to 121, and is written in Tulu.

Whish Coll. No. 1 (G) contains I. 122 to 165, and besides a fragment (I, 1-5) of Sayana's commentary on the Aitareya Aranyaka. It is written in Grantha characters from I. 122 to I. 141, 7, the rest being written in Tulu.

None of these MSS. bears a date. They can hardly be more than 100-150 years old. The Grantha MSS. are beautifully written. The greater part both of G and T is very correct.As to the relations existing to the other MSS., G and T can be treated as one MS. All that applies to G, applies also to T.

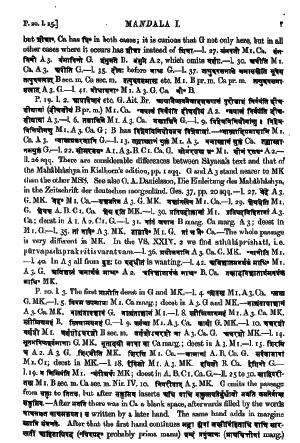

There can be no doubt that G and T belong to the A class. Especially clear is the relation between G and A 3. Dr. Winternitz points out the following passages as decisive on this point:

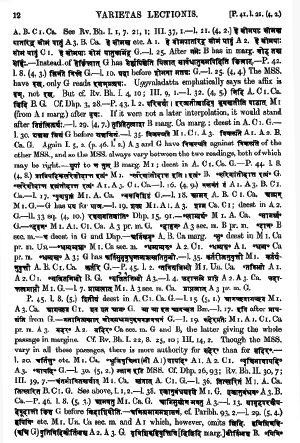

P. 11. l. 16. [x] before [x] is added in A 3. G, not in A 2. B. Ca.

P. 10. l. 20. A 3. G have [x], A 2. B. [x].

P. 10. l. 31. [x] A 3. G. [x] A 2. B. Ca.

P. 11. l. I. [x] deest in A 3. G.

P. 9. l. 3. [x] A 3. G against [x] in A 2. B. Ca.

P.9. l. 19. [x] is added after [x]: in A 2. B. Ca, but not in A 3. G.

P. 9. l. 24. A 3. G have [x], A 2. B. Ca [x].

P. 7. l. 37. A 3. G have [x], while A 2. B. Ca [x].

A very characteristic case occurs p. 104. l. 38 (18, 3), where the explanation of [x] is left out in A 3 pr. m. and added in the margin sec. m. Now in G we find a totally different explanation of [x]. This shows that A 3 and G come from the same source where [x]was not explained. In A 3 the lacuna was left, until a later hand supplied it in accordance with the other MSS., while the copyist of G supplied it by an explanation of his own.

Many other instances of agreement between A 3 and G will be found in the Varietas Lectionis. See p. I. l. 5, p. I. l. 9, p. 2. l. 8, p. 4. l. 25, p. 5. l. I, p. 7. l. 27, p. 8. l. 41, p. ll. l. 16, p. 15. l. 23, etc.

The same with T. See Var. Lect., p. 358. l. 34 (79, 9); p. 369. l. 2 ( (82, I); p. 389. l. 23 (87, I); p. 438. l. 19 (99). T seems, however, to stand nearer to A 2 and Ca than to A 3.

As to A 2 and T, see, e.g. Var. Lect., p. 362. l. I (80, 7); p. 441. l. 27 (100, 7) -- in the same line we find [x]after [x] in A 2. T only, and again, p. 442. l. 15 (100,9), [x] after [x] is left out in A 2. T-p. 451. l. 30 (102, 5), etc.

As to Ca and T, we find, e. g.

P. 374. l. 33 (84, 2). [x] in A. B, but [x] in Ca. T.

P. 386. l. 34 (86). [x] in A. B, but [x] in Ca. T.

Another characteristic passage occurs p. 460. ll. 10-12 (104, 8), where lit [x] etc. is added in the margin of Ca, apparently from A 2. In Ca pr. m. and in A 3 the passage is omitted. T gives quite an independent explanation, which tends to show that it goes back to the same source as A 3 and Ca, where this passage was omitted.

See also Var. Lect. for p. 369. ll. 17 and 19 (82, I); p. 376. l. 18 (84, 8); p. 380. l. 33 (84, 18); p. 382. l. 14 (85,1); p. 383.l. 3 (85, 3); p. 383. l. 23 (85, 5); p. 388. l. 4 (86, 5); p. 466. l. 10 (105, 13); p. 485. l. 22 (III, 5).

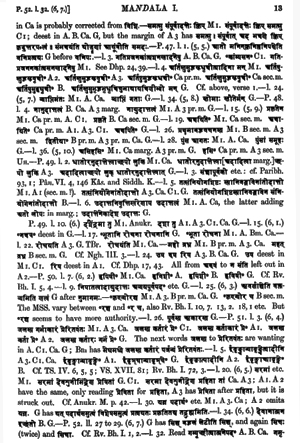

There are cases, however, where G differs from A, especially from A 2, while agreeing with Ca. Thus we find, p. 34. l. 33 (3, I), in Ca [x] with [x] in the margin, marked to be inserted after [x]. Now [x] is the reading of G.

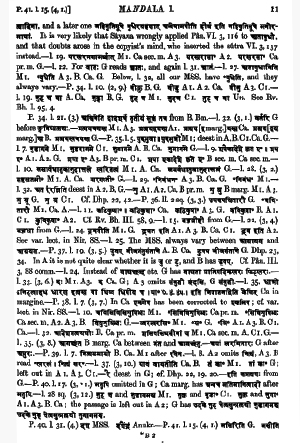

P. 2. l. 42. [x] Ca marg. with A 3. G for [x] A 2. B. Ca pr. m.

P. 9. l. 5. [x] Ca sec. m. with A 3. G. [x] A 2. B. Ca pr. m.

P. ll. l. 9. Ca sec. m. and A 3. G have [x] for [x] of A 2. B. Ca pr. m.

See also Var. Lect. for p. 2. l. 27; p. 4. l. 6; p. 9. l. 13, etc.

While in these cases Ca sec. m. -- that is, Ca as representing the A MSS. -- agrees with G, we find in a few other cases Ca Ppr. m. agreeing with G.

Thus we find, p. 561. l. 24 (123, 12), [x] standing in the margin of Ca, in G it is left out.

P. 567. l. 21 (125, 1). We find in Ca pr. m. and G [x] for [x].

P. 591. l. 8 (130, 4). We find [x] in Ca pr. m. G, while Ca sec. m. reads with A 2 [x].

See also Var. Lect. p. 569. l. 9 ( 125, 4).

These few cases point rather to a relationship between the C MSS. and G, than between the A MSS. and G. But the evidence in favor of a nearer relationship between these MSS. and the A class is much stronger. For we find not only G and. T going together with A 2, or with A 3, or with Ca sec. m., hut we find also a great number of cases where they agree with A, that is with A 2. A 3 and Ca.

Thus we find, p. 351. l. 6 (75, 4), [x] in A. Ca. T, while B reads [x]; and we find, p. 351. l. 28 (76, I), [x] in A. Ca. T, while B in accordance with the Sutra of Panini reads [x]. Ibidem, l. 25, we read [x] in B. Ca, while A. T agree in reading [x].

See Var. Lect. for p. 16. l. 9; p. 46. l. 29 (5, 4); p. 370. l. 22 (82, 4); p. 411. l. 20 (92, 4); p. 412. l. 16 (92, 6); p. 419. l. 33 (93, 8); p. 423. l. 22 (94, 7); p.471. l. 5 (107, I); p. 485. l. 36 (112, I); p. 489. l. 3I (112, 10); p. 21. l. 31; p. 56. l. 21 (7, 5); p. 82. l. 27 (12, 10); p. 416. l. 17 (92, 17); p. 591. l. 9 (130,4); p. 593. l. 3 (130, 8), etc.

A very characteristic passage which clearly proves that T stands nearer to A than to any other class of MSS. occurs p. 503. ll. 4-6 (113, 16). Here a whole passage, which stands in B. Bm. Ca, is omitted in the A MSS., and A 3 states the fact that the MS. was defective by saying [x]. Now we find in T a text quite different from that given in B. Bm. Ca. That is, the writer of T relied upon a MS. where the passage was omitted and he supplied it by an explanation of his own. He apparently did not know the reading found in B. Bm. Ca.

Another interesting passage occurs p. 507. l. 17 (114, 6). Instead of [x] we find in A [x]. Now the reading of T, [x], is evidently a conjecture caused by [x].

There are a few passages, p. 672. l. 34 (158, 4), p. 677. l. 4 (160, 3), and p. 677. l. 19 (160, 4), which seem to show a near relationship between D and G. But the fragments of D (see Var. Lect., p. 52) are too small to enable us to ascertain its exact place among the classes of Sayana MSS.

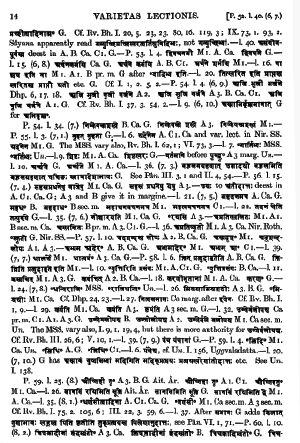

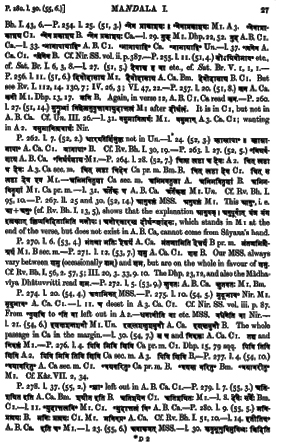

Though the relationship between G, T, and the A MSS. cannot be doubted, yet a mere glance at the Varietas Lectionis will show that G and T cannot be classed as simply A MSS., like A 1, A 2, A 3. As long as they give us a text which agrees with the text of Sayana which we are acquainted with, they stand nearer to A than to B. Ca, and nearer to A. Ca than to B. But in very many cases G and T offer a text of their own which widely differs from the text of A. B. Ca. We find sometimes quite purposeless alterations which cause no difference in meaning, sometimes emendations and conjectures, and especially enlargements of the received text of Sayana.

Thus in the well-known line [x] we find in G and T sometimes [x] for [x].

Or, in the colophon, for instance, of the first, sixth, and seventh Adhyaya of Ashtaka I, we find [x], while other MSS. read [x].

Numerous are the passages where G and T differ from all the other MSS. though saying the same thing; e. g.

P. 38. l. 5 (3, 7). G has [x], where the other MSS. read [x].

P. 351. l. 5 (75, 4). [x] T for [x] of A. B. Ca.

P. 360. ll. 29 and 30 (80, 3). T has [x], the other MSS. [x]; T has [x], the other MSS. [x], etc.

It is especially in the grammatical explanations where G and T show their independence; e. g.

P. 38. l. 11 (3, 7). G reads [x] for [x].

P. 366. l. 23 (81, 3). We find in T [x] for [x]. And again and again we find in G and T such various readings as [x] for [x] (3, 8), or, [x] for [x]: alone (3, 10), [x] for [x] (4, 2), [x] for [x]: very frequently, [x] instead of [x] etc. etc.

Instead of [x] (Pan. III. I, 34) G and T read constantly [x].

At the beginning of Ashtaka II, G adopts an independent style of interpretation. While the other MSS. give the prakriya at the end of a verse (e. g. l. 122, 6 seqq.), G inserts it after each word. In l. 123, I seqq., where the other MSS. have no prakriya at all, G inserts grammatical explanations of its own. Some of these variations were so useless that they have not been inserted in the Varietas Lectionis.

In very many cases, however, G and T offer readings different from A. B. Ca, not only in wording, but also in meaning. In all such cases the various readings have been noted. See, e. g. p. 2. ll. 20, 21, 28, 37; p. 5. ll. 18, 32; p. 6. l. 17; p. 7. l. 29; p. 9. ll. 30 alia 32; p. 23. l. 3 (I); p. 87. l. 22 (13, 10); p. 107. l. 9 (19, 2); p. 371. l. 21 (82,6); p. 384. l. 5 (85,6); p. 396. l. 34 (89.5); p. 567. l. 23 (125, I); p. 569. l. 10 (125, 4); p. 571. l. 19 (126, 3), etc. etc.

Sometimes the alterations in G and T arise from ignorance and misunderstandings, for instance, p. 708. l. 35 (164, 28), where G reads [x].

On p. 385. ll. 27 seq. (85, 10), T reads [x] and [x] for [x] and [x]. [x] in this passage can only mean 'a trough,' but the writer of T evidently replaced it by [x] in the sense of 'invocation.' See also p. 712. l. 15 (164, 36), where G reads [x] instead of [x].

Such cases are not frequent, but they may serve to remind us that the readings of G and T, even when they seem very plausible, cannot always claim the highest authority. That the Grantha MSS. do not come nearer to the archetypus than A. B. Ca can be seen from passages like p. 587. l. 10 (129, 8), where G shares with A. B. Ca. the quite impossible reading [x]; or, p. 637. l. 8 (142, 9), where G, together with A. Ca., adds a grammatical explanation of [x] at the end of the verse, though [x] does not occur in the verse. See also Var Lect., p 542. l. 3 (120, 7).

The real value of the Grantha and Tulu MSS. arises not so much from their greater antiquity as from the fact that they were written by very learned Pandits who did not allow corrupt readings to remain, but corrected them according to grammar, and according to Sayana's usual style. These corrections are in many instances excellent, but they have to be judged by their own intrinsic value. Where A. B. Ca, or A. Ca, stand against G (or T), the reading of A. B. Ca has been adopted wherever it was possible. Only where the other MSS. were decidedly corrupt have the readings of G and T been adopted against the authority of A. B. Ca, though never without a note to that effect in the Varietas Lectionis. Where G and T agree with A. Ca, they have the value of an A MS.A few orthographical peculiarities of the Southern MSS. may here be mentioned. In the text, G and T generally read [x] for [x] (e. g. I. 81, 4), [x] for [x] (e. g. I. 81, 5), [x] for [x] (e. g. I, 82, 3) etc.

Instead of [x], they always read [x], e. g. [x], etc.

Instead of [x], G and T generally read [x], e.g. [x] I. 9, 1, [x] I. 15, 1. See Var. Lect. to p. 90. l. 19 (14, 6). G writes even [x] instead of [x]: p. 103. l. 27 (18, 1).

It may be useful also to remember what mistakes are likely to arise in MSS. written in the Grantha and Tulu alphabets.

Mistakes often arise from confounding [x] and [x], [x] and [x], [x] and [x] -e and initial u, e.g. [x] and [x], and [x], [x] and :, e. g. [x] and [x], Visarga ([x]) and Anusvara [x] and Anusvara, [x], [x] etc., and [x], [x] etc., e. g. [x]: for [x], frequently [x] for [x], [x] for [x] etc., [x] and [x], [x] and [x], [x] and [x]. We often find [x] for [x], [x] for [x], [x] for [x], [x] for [x], possibly due to the peculiar Southern pronunciation on the part of the reader.

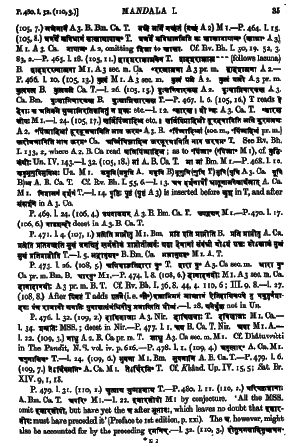

That A 3, the Berlin MS. of Ashtaka I, belongs to the A class will be seen from numerous cases quoted in the Varietas Lectionis. Decisive are such passages as the following:

P. 213. l. 30 (40, 6). Both A 2 and A 3 have [x].

P. 216. l. 16 (41,7). Both A 2 and A 3 repeat [x] after [x].

P. 217. l. 27 (42, 1). Both A 2 and A 3 have the Virama in [x].

P. 315. l.7 (64, I). A 2 and A 3 agree in the mistake [x] for [x]. In A 3 it was corrected secunda manu.

P. 317. l. 18 (64, 7). A 2 and A 3 share the mistake [x] instead of [x].

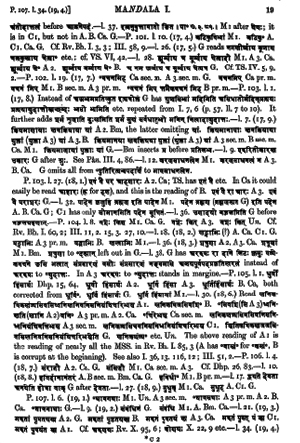

The importance of MS. Ca and its position among the Sayana MSS. have been fully discussed in the preface to vol. ii of the first edition (see above, p. xxxi seq.). It has been shown from many passages of the second Ashtaka that Ca is the original of all the C MSS., but that in its corrections it often represents the A MSS. The following examples may show that the same holds good also for the first Ashtaka:

P. 284. l. 12 (56, 5). Ca reads with B. C I [x], but [x] is corrected to [x], the reading of A 2. A 3.

P. 182. l. 7 (34, 3). We find [x] after [x] in A 3. The same addition is found in the margin of Ca.

P. 293. l. 32 (59, 7). Ca pr. m. has the right reading of [x], but it is corrected to [x], which is the reading found in A 3.

Frequently A 3 and Ca sec. m. agree, when they differ from A 2. See, for instance, p. 2. ll. 27, 42; p. 4. l. 6; p. 7. ll. 20, 23; p. 10. l. 42; p. 11. ll. 4, 9; p. 15. l. 31; p. 16. l. 24; p. 17. ll. 20, 33; p. 19. l. 31 ; p. 30. l. 6 (2); p. 30. l. 28 (2, I); p. 48. l. 36 (5, 10); p. 64. l. 7 (8, 10); p. 65. l. I (9, 2), etc. etc. Characteristic passages occur p. 554. l. 34 (122, 10), where A. Ca agree in the wrong reading [x]; p. 570. l. 3 (125, 6); p. 702. l. 22 (164, 16), etc.

It is possible that some portions of A 2 were copied from Ca, for in some places they agree in the most palpable mistakes. The most striking case occurs p. 670. l. 27 (157, 6): in Ca, fol. 88, 1. 8, we read [x] and [x] in the margin, and l. 9 we read [x] etc. Now in A 2 we read [x]. A 2 evidently mistook the [x] in Ca marg. for a correction of [x].

P. 727. l. 12 (166, 6). For [x] Ca reads [x], but the[x] can easily be mistaken for [x], and thus A 2 reads [x].

As will be seen from the preface to vol. ii of the first edition, MSS. become much scantier from the beginning of the second Ashtaka. The A class now is chiefly represented by A 2, and by corrections in Ca, which have evidently been taken from an A MS. Some of the C MSS., especially C 2, contain often long portions copied from an A MS. From Ashtaka, III. 3, 27 to the end of the Ashtaka the fragment marked Aa is very important, and seems to be the original of A 2. The B class is now represented by B 1, from which all other B MSS. have been derived. The C class is chiefly represented by Ca, the other C MSS. being but rarely of use by the side of Ca. For the whole of vol. ii (Mandalas II to VI) MS. Ca has been collated throughout by Dr. Winternitz for the purpose of revising the text of the first edition.

MSS. A 2 and B 1 have been consulted whenever there was any doubt or difficulty, and their readings have been noted in the Varietas Lectionis in all cases where they seemed to be of any importance.

Several of our MSS. of Sayana have evidently been used for study in India, and have been corrected by native scholars, either independently or on the authority of other MSS. After a time some of these corrections, inserted originally in the margin, would, when the MS. was copied again, be inserted in the text, and thus obscure from time to time the original relationship of the MSS. Such cases have been noted in the Varietas Lectionis, and various readings have often been inserted, not so much for their own sake, as for the light which they throw on the mutual relation of the MSS. The fourth Ashtaka in A 2 and Ca is not written by the same hand which wrote the third. In this Ashtaka A 2 has many corrections, but the original text agrees with Ca.

There are some portions of the commentary where B and A 2 go together and differ from Ca, others where B goes with Ca and differs from A 2. See, for instance, IV. 4, 8; 4, 15; 23, 1. How closely B and Ca hang together is seen in such passages as V. 54, 4. 6; 55, 9; 57, 6; 58, 6.

On the whole A and Ca stand nearer to each other than B stands to either. Again, B comes nearer to Ca than to A. The most difficult parts of Sayana's commentary are those where all the three chief MSS., A. B. Ca, agree in false readings. Such a portion of the commentary begins, for instance, with I. 173, 6.In cases where the text adopted in the first edition has been altered, the various readings supplied by the MSS. have been noted, while the reading adopted in the first edition has been added and marked M 1, at least in all cases where it seemed of any importance to do so. It should he remembered, however, that from the beginning of the second Ashtaka M 1 means simply Editio princeps, and does not include A 2 and B.

Sometimes, and more particularly in the beginning of Ashtaka IV, and again towards the end of Mandala, VI, even our best MSS. (A 2. B 1 and Ca) are often very deficient and faulty, and readings had to be adopted in the first edition unsupported by any of these MSS. These readings have been retained in the second edition, but as they may have had the authority of some MS. which, having been returned to its owner, is not available for the new edition, they have been marked by MS., in order to distinguish them from purely conjectural emendations. Thus when we read in the Varietas Lectionis, p. 60. l. 38, [x] MS., [x] A 2. B. Ca, this means that [x], though unsupported by A 2. B. Ca, may have been the reading of some MS. If, on the contrary, [x] had been a mere conjecture, the Varietas Lectionis would have given [x] A2. B. Ca.

In the few cases where the text of the Rig-veda is doubtful, the Samhita and Pada MSS. of the Bodleian Library have been once more consulted. A new accentuated Samhita MS. (S 4), in my possession, containing all the eight Ashtakas has been made use of. Ashtaka II is dated Saka 1679, the copyist's name is Karopanamaka Narayana. The other Ashtakas are written by Navathyopanamaka Kesavadeva. Ashtakas I, IV, and V are dated Saka 1707; Ashtaka III, Saka 1708; Ashtaka VI, Saka 1705; Ashtaka VII, Saka 1704; Ashtaka VIII, Saka 1709.Two more Pada MSS. have been used for this new edition, viz. Colebrooke's MS. (P 3) India Office Library, Nos. 20-27, and Wilson 439-442 (P 4) of the Bodleian Library, both accentuated.

As to the rules of Sandhi, the principles laid down in the preface to vol. i of the first edition (above, p. xxiii seq.) have been strictly adhered to, and carried out even more rigorously than before. Wherever Sandhi is broken, there was a definite reason for it. And both with regard to Sandhi and the division of sentences every effort has been made to be as consistent as it is possible in so large a work as Sayana's commentary.

OXFORD,

October 1, 1890.

F. MAX MULLER.