7. Treasures

WHAT is the first food you remember, remember seeing it if not eating it? Well, the first food I remember from my early childhood in San Francisco in the early 'eighties was breakfast food: cracked wheat with sugar and cream, com meal with molasses and farina with honey. But after that the first food that I saw and clearly remember was souffle fritters which of course were not included in a diet prescribed for a child. Nora, my mother's cook, fortunately stayed on long enough for me to taste her fritters. Nora left my mother's kitchen when she was nearly forty years old to marry a well-paid workman and she proceeded to produce five or six children. Maggie, the nurse, would go to see her and on her return would tell the incredible story that Nora who had been such an exquisite cook was now feeding her family, including the youngest born, on canned food. She was a precursor. This is the way to prepare

NORA'S SOUFFLE FRITTERS

Put I cup water, 1/2 cup butter and a pinch of salt into a saucepan on the fire. When the butter has melted and the mixture is about to boil remove from the fire and quickly stir in 2 cups sifted flour. Stir vigorously with a wooden spoon. Place on a very low flame until the mixture leaves the saucepan dry. Turn into a large bowl. Cool for 10 minutes. Then continuing to beat vigorously add 8 eggs, one at a time, thoroughly incorporating each egg before adding another. While beating lift the mixture high in the air so that as much air as possible will enter. Do not stir but beat steadily for about 20 minutes. Put aside in a cool place, but not in the refrigerator, for 2 or 3 hours. When ready to use heat sufficient oil for deep frying to medium heat. You will have rolled the mixture into balls the size of a large walnut in the centre of which you will have placed 1/2 teaspoon currant jelly. Increase the heat. The fritters will rise to the surface, swell, turn over and become golden brown without your aid. At this point remove them at once from the oil, coat generously with confectioner's sugar and serve immediately.

Nora's ice cream is still remembered. It was frozen in a then lately invented "automatic" freezer, there was no cranking to be done. My mother revelled in each year's invention. How she would have enjoyed the present gadget of the week. I found the directions for the use of the "automatic" freezer pasted in the back of the cook-book she had bought for Nora. Many years after, Maggie told my mother that Nora was completely illiterate and so she had read aloud to Nora the recipes she needed and had written down the daily expenses every evening. Maggie had not wanted my mother to know this while Nora was in her service, she thought it would embarrass both of them.

NORA'S ICE CREAM

1 quart whipped cream sweetened with 3/4 cup icing sugar. Add 1-1/4 cups raspberry jelly slightly melted. Fold in the beaten whites of 5 eggs. Freeze.

It surprises me, recalling these two of Nora's delights, to find that my collecting of treasures commenced so very, very long ago and that many of them, consequently, are no longer treasures. One must have been more innocent and more inexperienced than one likes to think of one's self as having been. If taste is matter of choice, the quantity of rejections for this book is neither flattering nor encouraging. The wastepaper basket is too small. But if there are amongst the discards proofs of an undiscerning past, there will also, I hope, be signs of more recent perspicacity in those that are offered here.

My collecting of treasures began with Sweets -- cakes and ices, desserts and candies -- double evidence of their date. For when one is young, that is what interests one most; the rest follows. So this is one of the earliest.

SCHEHEREZADE'S MELON

Cut a piece from the stem end of the melon. Scoop out in as large pieces as convenient as much of the pulp as is possible without piercing the melon. Empty all the juice, dice the pulp in equal quantities (this will depend upon the size of the melon) as well as pineapple and peaches. Add bananas in thin slices, and whole strawberries and raspberries. Sugar to taste. When the sugar mixed with the fruit has dissolved put the fruit and their juice in the melon. Cover with four parts very dry champagne and one part each of Kirsch, Maraschino, Creme de Menthe and Roselio. Put in refrigerator overnight. [1]

This dessert and a complicated Bavarian cream which had a similar flavour from its including the same fruits and precisely the same liqueurs and cordials were early favourites. The recipe for Scheherezade's Melon is preserved in my mother's handwritten cook-book.

Another early recipe has for the last sixty years been known amongst my friends as

ALICE'S COOKIES

On a floured board sift 2 cups flour. You will require 2-1/2 cups unsalted butter, the yolks of 6 eggs and 1 cup icing sugar with which a vanilla pod has been pounded and sifted. With the tips of the fingers very lightly work in one-sixth of each of the ingredients until all of each of them has been worked in. It may take more flour, depending upon the size of the yolks of the eggs and the quality of the butter. Only add enough flour to roll. Roll to about 1/4-inch thickness. Cut with a round cookie cutter of any size that suits, but not more than 2-1/2 inches in diameter. Place on cookie sheets and bake in 300° oven for about 1/4 hour. The cookies should not be coloured. When done remove very carefully from cookie sheet with a metal spatula. They are as fragile as they are exquisite. Cover generously with sifted icing sugar. Do not put in tin box until cold. If the box has a cover that closes hermetically, the cookies will keep for two weeks or more.

As these cookies take some time to prepare, eventually they were replaced by an adaptation of Scotch short bread.

NAMELESS COOKIES

Cream 1 cup butter, very slowly add 1/4 cup sifted icing sugar and about 2 cups sifted flour. It should take about 20 minutes' active stirring. Do not beat but stir. When about half the flour has been worked in add a tablespoon best white curacao and I teaspoon brandy. The dough should only be stiff enough just to hold its shape when rolled by one's extended fingers into small sausages a thumb's length and width. Place on cookie sheet an inch apart -- they will spread in the oven, which should be preheated at 275°. The cookies should be very pale, indeed not coloured at all by the heat. Twenty minutes' baking will be sufficient. Remove carefully with metal spatula from cookie sheet and sieve icing sugar over them at once. In a well-covered tin box they will keep three weeks. These cookies have a less delicate texture than the Alice's cookies but are a time-saving substitute.

This recipe is one that was prepared at my request for a lunch celebrating a birthday to which some of my schoolmates had been invited. It is named after a cook.

KATIE'S CAPON

Brown a capon in 6 tablespoons butter in an enamelled pot over medium heat. Cover and reduce heat. After 1/4 hour add 3/4 cup hot water, 3/4 cup hot port wine, the zest of 1/2 orange, 1 teaspoon salt, 1/4 teaspoon pepper and a pinch of cayenne pepper. After 20 minutes, baste every 1/4 hour. The capon will be cooked in 3/4 hour. Remove from pot, place on heated serving dish. Skim juice in the pot and strain. Replace over lowest flame. Stir into pot 3/4 cup heavy cream. Add 4 tablespoons butter. Do not allow to boil, do not stir but tip pot in all directions. Serve very hot. The gravy is poured over the capon so that the juices of the capon when carved enter into the sauce. It is equally delicious cold. To serve cold the juice must have been thickened with rice flour or arrowroot -- as in those days one did for more delicate food -- and cooled before pouring over the capon.

When treasures are recipes they are less clearly, less distinctly remembered than when they are tangible objects. They evoke however quite as vivid a feeling-that is, to some of us who, considering cooking an art, feel that a way of cooking can produce something that approaches an aesthetic emotion. What more can one say? If one had the choice of again hearing Pachmann play the two Chopin sonatas or dining once more at the Cafe Anglais, which would one choose?

To return to our muttons.

LEG OF MUTTON A LA MUSCOVITE

Chop 3 large onions, 3 large carrots and 3 heads of celery. Brown them lightly in 4 tablespoons butter in a saucepan over medium heat. Add 1 cup boiling water and 1/4 cup boiling vinegar, 1 bay leaf, 2 cloves of garlic, 3 cloves, 1 teaspoon salt and 1/2 teaspoon pepper. Cover, reduce heat and boil for 20 minutes. Remove from heat and when cold, strain. Place the leg of mutton in a preheated 475 ͦ oven and after 20 minutes commence to baste with hot juice of vegetables. It will take about 1/2 hour to roast, according to the size of the meat.

MUTTON CHOPS IN DRESSING-GOWNS

Cook 6 mutton chops in a covered saucepan over medium heat in a hot bouillon that scarcely covers, with a very little salt and a bouquet of the usual herbs. When they are cooked, or in about 15 minutes, remove chops from bouillon. Return bouillon to medium heat and reduce to a glaze. Then replace chops in the saucepan and glaze them. Remove from saucepan and spread on each chop this mixture: finely chopped parsley, 1 finely chopped shallot, 2 chopped hard-boiled eggs, 1/4 lb. finely chopped mushrooms which have been cooked for 8 minutes in 2 tablespoons butter and 1 teaspoon lemon juice, 1/4 teaspoon salt and a good pinch of pepper. These ingredients are bound together with 3 tablespoons heavy cream. Paint the mixture on the chops with melted butter, dip in fine fresh bread crumbs. Place for IS minutes in a preheated 500 ͦ oven. Serve very hot.

In my collection of recipes there is one, Rosbif de Mouton, from a manuscript cook-book lent to me by a French friend. Rosbif is what the French call roast beef. It reminds one of the signs one used to see in Paris at smart tea shops -- Le Fif o'Clock a Toutes les Heures (the five o'clock (tea) at all hours). The recipe for the Roast Beef of Mutton is by no less a person than Alexandre Dumas, senior, author not only of the Three Musketeers but of The Large Dictionary of the Kitchen. This recipe is entirely devoted to the manner he recommends for skewering the hind half of a sheep that is to be roasted on the spit. For this reason it is not given, but there are in my collection two other of Dumas' recipes. They too are for the preparation of mutton. One is for

FOIE DE MOUTON A LA PATRAQUE

(Gimcrack Mutton Liver)

Put a sheep's liver cut in thin slices into very hot olive oil. Cook each side of the slices for 5 minutes. Remove the meat and add to the oil the juice of 2 lemons or the same amount vinegar, garlic and very finely rolled toast. Mix these well together for 2 minutes and return the meat and some chopped parsley, and saute until the liver is cooked. Serve hot.

It is dated by the use of toasted crumbs to thicken sauces; in fact, though, they were little used as late as Dumas senior's lifetime. This is the other Dumas recipe:

THE SEVEN-HOUR LEG OF MUTTON

In an earthenware pot place the rind of pork fat cut in small pieces. Interlard a leg of mutton with ham, garlic and lard. Put your leg of mutton into the pot with salt, pepper, 2 large onions, 3 glasses water, 1 glass white wine. Cover the pot with a plate and paste paper around the pot and the plate. In the plate pour some wine and allow it to simmer for 7 hours.

From the same rich fund that produced the two Dumas recipes there are others to offer, beginning with

CHICKEN A LA REINE MARIE

In a casserole over medium heat place 5 tablespoons butter and 1-1/4 lbs. veal knuckle cut in four pieces. Let them brown lightly on all sides and remove from casserole. Do not allow the butter to bum. Add 4 large onions cut in thick slices and brown them. Remove from casserole. Put 4 large carrots cut in thick slices in the casserole and brown them. Add the pieces of veal knuckle and the onions. Reduce heat and let them cook together for 1/4 hour, add 1/2 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Add a calf's foot cut in four pieces. Cover with 6 cups hot water and add 1 large bouquet. Cover the casserole and over lowest flame simmer for 4 hours. Watch carefully that the water does not completely evaporate. Then remove the veal knuckle, the calf's foot and the bouquet. Mash well through a sieve so as to extract all the juice the vegetables contain. Melt 4 tablespoons butter in a saucepan over low flame. Add 1 tablespoon flour and, constantly stirring with a wooden spoon, let it brown lightly. Very slowly add the strained juice. Let this sauce simmer until thickened. Cut a fine chicken into joints and place in an iron pot in which 7 tablespoons butter have been melted. Over medium heat brown all sides of the pieces of chicken. Add 1/2 teaspoon salt and 1/4 cup good dry white wine. Cover and simmer for about 3/4 hour, depending upon the size of the chicken. The giblets will have been cooked slowly for about 2-1/2 hours with 1 carrot, 1 turnip and 1 leek. This should produce 1-1/2 cups concentrated bouillon. In a small saucepan melt 4 tablespoons butter over low heat. Add 1 tablespoon flour. Stir with a wooden spoon and mix thoroughly. Add the bouillon and when it commences to boil slowly pour in 1-3/4 cups heavy cream. Add 1/2 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Bring to the boil and remove from heat. Arrange the pieces of chicken in a manner to resemble an uncut chicken on a serving dish, and when the sauce is tepid pour over the chicken. Serve cold.

This is a very satisfactory principal dish for hot weather. A green salad accompanies it.

From the same source,

A SALMON PATE

For the crust, sieve 4 cups flour in a bowl with 1-3/4 cups butter, 1/4 teaspoon salt and mix with a pastry blender. Add only enough cold water to hold the dough together. Do not mix it too much. Put aside covered for 1/2 hour. Then roll it to a square of about u inches. Fold it from top to centre and from bottom to top. Fold the sides in the same manner. Put aside covered for 10 minutes. Roll and fold a second time. Put aside covered. (The dough can be rolled in wax paper in these modem days instead of covered, as this old recipe recommends.) Boil 2 eggs for 11 minutes. Boil 1 cup rice in 3 cups water for 15 minutes. Dry thoroughly in the oven. Roll the dough to a 1/4-inch thickness, then roll all around the edge to half that thickness. This will leave the centre with a double thickness. In the centre spread a layer of rice (it must be perfectly dry and cold) of about a 1/3 inch in thickness, salt and pepper. Cover with a layer of heavy cream, 1/3 inch in thickness. Then place on the cream 1 lb. raw salmon cut in three slices, let them overlap, salt and pepper them. Cover with another layer of heavy cream 1/3 inch in thickness. Sprinkle the 2 hard-boiled eggs finely chopped over the cream. Cover with a layer of rice of 1/3 inch in thickness, salt and pepper lightly. Paint the uncovered dough lightly with water and cover the filling from the top and bottom. Then from the sides. Paint the top and the sides with an egg mixed with 3 tablespoons water. Bind the sides of the pate with a piece of buttered paper and tie with a string to hold it in place. Prick the top of the pate with a fork in a number of places. In the centre of the top cut a small round opening of 1 inch in diameter, remove the small piece of dough. Slip the pate on to a lightly buttered baking sheet and place in a 500° preheated oven. Lower the heat in 10 minutes to 400°. As soon as the pate commences to colour, lower to 375°. In 1/2 hour remove the paper that binds the sides and bake for 1/4 hour longer. Remove from oven, pour into the hole in the centre 4 tablespoons melted butter and serve.

The recipe for this omelette comes from the cook-book of Georges Sand. Should it not therefore be called

OMELETTE AURORE

Beat 8 eggs with a pinch of salt, 1 tablespoon sugar and 3 tablespoons heavy cream. Prepare the omelette in the usual manner. Before folding it, place on it 1 cup diced candied fruit and small pieces of marrons glacis which have soaked for several hours in 2 tablespoons curacao. Fold the omelette to keep the fruit in place, on fireproof serving dish. Surround with marrons glaces and candied cherries. Cover at once with this Frangipani cream, made by stirring 2 whole eggs and 3 yolks with 3 tablespoons sugar until they are pale-lemon coloured. Then add 1 cup flour and a pinch of salt, stirring until it is perfectly smooth. Add 2 cups milk and mix well. Put in a saucepan over lowest heat and stir until quite thick. It must not boil. Be careful that the cream does not become attached to the bottom or sides of the saucepan. When it has thickened remove from heat and add 2 tablespoons butter and 3 powdered macaroons. Stir and mix well. Pour over omelette and sprinkle 1/4 cup diced angelica over the cream. Then sprinkle 6 powdered macaroons on top and 3 tablespoons melted butter. Place the omelette in a preheated 550° oven only long enough to brown lightly.

OMELETTE IN AN OVERCOAT

Put in a saucepan over medium heat 3 tablespoons butter with 1 tablespoon chopped parsley, 3/4 cup mushrooms cut in thin slices, stems included, 2 chopped spring onions and 2 shallots finely chopped. Stir them until they are coated with butter, then add 1-1/2 tablespoons flour and 1-1/2 cups milk. Continue to stir until the sauce thickens. Lower heat after it comes to a boil and simmer for 5 minutes. Pour into the serving dish. Place on it 6 mellow eggs, which are eggs placed for 4 minutes in boiling water, removed and placed under the cold-water tap, and when they are cold carefully shelled. They are then placed in a saucepan of boiling water, covered and allowed to stand in it for 5 minutes. Prepare a 6-egg omelette in the usual manner, entirely cover the eggs and sauce with it. Sprinkle the top with 2 tablespoons melted butter, then a thick covering of finely toasted breadcrumbs and once more a sprinkling of 2 tablespoons melted butter. Brown in preheated 550° oven. Serve at once.

And one more omelette, but without a name, so it will be called

OMELETTE SANS NOM

Stir in a bowl the yolks of 4 eggs with 3/4 cup heavy cream, a pinch of salt and 1 tablespoon grated Parmesan cheese. Mix well and add 5 tablespoons very soft butter. Beat the whites of 4 eggs and fold the egg-cream mixture into them at the same time as 1-1/2 cups tiny dices of ham. Put in a preheated fireproof well-buttered dish for serving and place in a preheated 500° oven for 5 minutes. Remove from oven and quickly cover with I cup heavy cream on which 1/4 cup tiny diced ham is sprinkled. Return to oven, lower heat to 400° and brown for a little less than 1/4 hour more. Serve at once.

ROAST KIDNEYS

Cook in a frying pan over medium heat a veal kidney. Cut into small pieces 6 tablespoons butter. Stir until all the pieces are covered with butter. Add salt, pepper, 1/2 cup hot Madeira. Lower heat and cover. Cook for 6 minutes. Remove pieces of kidney with a perforated spoon and put aside. Add to the frying pan 2 tablespoons butter and brown lightly on each side six slices of bread and remove from pan. Put kidney through the meat chopper. Add 7 tablespoons butter, 1 tablespoon chopped parsley, 1 chopped shallot, 1/2 teaspoon salt, 1/4 teaspoon pepper and the yolks of 4 eggs. Mix well. Beat the 4 whites of eggs and fold into the chopped mixture. Place the browned bread on a fireproof serving dish, put a layer of the mixture on each piece and flatten the top with a knife. Cover with fine breadcrumbs and melted butter. Place in preheated 400 ͦ oven for 20 minutes. Serve with this.

RAVIGOTE SAUCE

Put in a small saucepan over low heat 1 cup of strong bouillon, 1 teaspoon vinegar, 1/3 teaspoon pepper, 1/4 teaspoon salt, 1 tablespoon butter mixed with 1 teaspoon flour. Stir until it commences to boil. Allow to simmer for 5 minutes. Then mix 1 teaspoon chopped chervil, 1 teaspoon tarragon, 1 teaspoon chopped capers, 1 teaspoon chopped parsley, 1 teaspoon chopped shallot and 1 crushed clove of garlic. Put in a mortar and pound well. Then add them to the sauce and heat. Stir until the sauce is green. Do not boil. If the herbs are not finely enough powdered -- which would be a mistake and a pity -- strain and reheat in another saucepan but do not allow to boil. Serve at the same time as the kidneys.

In the collection of recipes there are certainly a disproportionate number for the preparation of chickens, but the French when in doubt always answer chicken. This is a very witty way to present a

QUADRIPARTITE CHICKEN

Cut a fine chicken in four pieces. Cover each piece completely with a thin slice of fat back of pork and skewer or tie to keep in place. Put them in an iron pot over medium heat with 4 tablespoons butter, brown very lightly and add 1 truffle, 1 large slice of ham, a bouquet of parsley, a twig of thyme, 1/2 laurel leaf and several leaves of basil or 1/4 teaspoon powdered basil, 1 clove, salt, pepper and 3/4 cup dry white wine. Simmer covered for 3/4 hour. Chop the truffle, the slice of ham, the yolk of 1 hard-boiled egg and 10 capers, each of them separately chopped. Remove the pieces of chicken to the serving plate placing each piece to reconstruct the chicken, but flat. Skim the sauce through a strainer and replace over heat. Bring to a boil, stir the bottom and sides of the pot and add 1-1/2 tablespoons butter and 1 tablespoon flour which have been thoroughly mixed together. Stir and boil gently for 3 or 4 minutes until the sauce is thickened. Pour over the four pieces of chicken. Cover one with chopped ham, another with yolk of egg mashed through a sieve, another with chopped truffle and the last one with chopped capers.

This recipe for rice taught me how to judge when rice was sufficiently cooked. Besides this it is an excellent dish.

RICE A LA DREUX

Wash, drain and thoroughly dry 1-1/2 cups rice. Put on a saucepan over medium heat and melt 3 tablespoons butter. Add the rice and stir with a wooden fork until all the rice is covered with the butter. Lower heat and continue to stir for 10 minutes. Then add 3 cups chicken broth, 1/2 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper and cover. The rice is cooked when small holes appear on the surface. Put the saucepan uncovered in a very slow oven to dry the rice. Cut a veal kidney in thin slices, put in a saucepan in which 3 tablespoons butter have been melted. Over medium heat, brown lightly and add 1 tablespoon flour. Mix well and add 3/4 cup hot chicken bouillon and 1/4 cup hot Madeira. Reduce heat as soon as it commences to boil. Add 1/4 teaspoon salt, 1/8 teaspoon pepper and a pinch of powdered mace or nutmeg. Cover and allow to simmer for 10 minutes. Scramble 8 eggs in saucepan in which 2 tablespoons butter have been melted, add 1/4 teaspoon salt and 1/2 cup cream. Be careful not to overcook. The rice having been placed in a ring mould and tapped so that there will be no holes is now removed from mould on to the serving dish. The centre of the dish is filled with the scrambled eggs and the slices of kidney are placed around the rice and their sauce poured over them.

MUSHROOM SANDWICHES (1)

Mushroom sandwiches have been my speciality for years. They were made with mushrooms cooked in butter with a little juice of lemon. After 8 minutes' cooking, they were removed from heat, chopped and then pounded into a paste in the mortar. Salt, pepper, a pinch of cayenne, and an equal volume of butter were thoroughly amalgamated with them. Well and good. But here is a considerable improvement over them, also called

MUSHROOM SANDWICHES (2)

The method is the same as above up to a certain point. These are the proportions. For 1/4 lb. mushrooms cooked in 2 tablespoons butter add 2 scrambled eggs and 3 tablespoons grated Parmesan cheese and mix well. The recipe ends with: This makes a delicious sandwich which tastes like chicken. A Frenchman can say no more. Which gave me the idea of introducing chicken sandwiches in which chopped and pounded chicken was substituted for the mushrooms. Naturally they were well received.

So we are back to chicken with some recipes for them, delicious or original. This one is both.

A HEN WITH GOLDEN EGGS

Put a hen in a saucepan over very high heat. It should be covered with cold water, and when it is about to boil, the water is skimmed. Then reduce the flame, add salt, pepper, a bouquet of laurel leaf and a sprig of thyme and parsley, 1 large onion, 1 large carrot, 1 leek and 2 large stalks of tarragon. It will depend upon the age of the hen whether it will be tender in 1-1/2 or 3 hours. It should not cook beyond being tender. Before the end, add 1/2 lb. mushrooms. Let them boil in the court-bouillon for 10 minutes. Remove chicken. If there is more than 3 cups bouillon, reduce and strain, add 1 cup heavy cream and 1 cup butter. Do not allow to boil. Do not stir but tip saucepan in all directions. In the cavity you will place the golden eggs that are made in this way. Boil 2 lbs. potatoes in their jackets. When tender, peel and put through the mechanical vegetable masher. Then beat hard while slowly adding 1/2 cup butter and the yolks of 6 eggs. Mould into balls and shape to imitate eggs, dip into a bowl of melted butter and cover generously. Put into frying pan in which 5 tablespoons butter has been melted over medium heat, heat thoroughly but do not brown. Stuff the cavity of the hen with these eggs. Pour the sauce over the chicken and surround with the rest of the golden eggs.

This is an amusing way to present a chicken. It is a delicious dish.

CHICKEN A LA COMTADINE

Cut a spring chicken into eight pieces, salt and pepper them. Lightly brown them in 4 tablespoons butter in a pan over medium heat. Lower heat and cover the pan, let them cook for 20 minutes, shaking the pan frequently. Remove from heat and pour over them the contents of the pan. Then pour into the pan 1/2 cup good sweet Italian vermouth (Cinzano or Rossi). Heat it and light it. While still lighted replace the pieces of chicken, extinguish flame. Stir to heat and add 1 tablespoon tomato jam, a good pinch of cinnamon, and one of cayenne pepper. Stir the chicken for 5 minutes to coat each piece with the sauce and serve.

And this fowl with wine --

DUCK IN PORT WINE

Put 24 figs in a wide jar to marinate for 36 hours in an excellent dry port wine and cover hermetically. Put the duck in a preheated 450 ͦ oven. After 1/4 hour commence to baste it with the port wine in which the figs have been macerating, and which has been heated. Continue to baste every 15 minutes. Turn the duck on each side so that the legs are browned. When all the port has been used for basting put the figs around the duck and baste with veal bouillon. Continue to baste. The duck will be cooked in an hour unless it is a very old duck indeed.

No duck interests me after the month of September. Ducks should be goslings and it is a pity that they are not hatched later in the season, for they are really a late autumn and winter dish.

This is a very pretty dish and, though original, not outrageous. On the contrary, it is a satisfactory combination of colour and flavour.

PINK POMPADOUR BASS

Bass should not be cooked in a court-bouillon. Put a 4 lb. bass into hot salted water. As soon as the water boils again reduce at once to low flame. The fish should simmer. The water should tremble or shudder, as the French say, for 3/4 hour. Remove from kettle and delicately remove the skin, and when quite cold place on serving dish and cover with a pale-green mayonnaise made with 2 yolks of eggs, 2-1/2 cups oil, the juice of 1 lemon, salt and pepper and enough cress, chervil and tarragon leaves in equal quantities pounded in a mortar until reduced to a smooth paste to make in all 4 tablespoons. Boil 2 lbs. potatoes in their jackets, peel and put in the electric blender with half the volume of boiled beetroots. When they are mixed add I tablespoon oil and juice of 1/2 lemon, salt and pepper and enough thick cream to put in the pastry tube, and decorate around the fish.

And this is another attractive and tasty dish.

GIANT SQUAB IN PYJAMAS

Completely cover a giant squab (young pigeon) with a thin slice of back fat of pork. Tie it to keep in place, cover with a thick coating of butter. If possible to secure, cover the pork fat with vine leaves. Place in a cocotte with an onion, a crushed clove of garlic, a bouquet, 1/3 cup diced skin of back fat of pork, 3 tablespoons butter and pepper, and 1/3 cup brandy. Cover and simmer over low heat for 2 hours. Remove lard and place squab on serving dish. Prepare an aspic by soaking 1 tablespoon gelatine in 1/2 cup water. Bring 3/4 cup port wine and 3/4 cup chicken bouillon to a boil. Melt the gelatine in the hot mixture. When it is cold and sufficiently thick, cover squab. Shred 1/2 red cabbage, season with 1/2 teaspoon salt, 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Add 1-1/2 tablespoons olive oil and the juice of I lemon. Mix well and surround the squab with this salad. Surround the squab with a few nasturtium flowers and place a few around the edge of the salad.

PHEASANT WITH COTTAGE CHEESE

Fill the cavity of a pheasant with cottage cheese. Sew the cavity together securely. Tie round the pheasant a thin slice of fat back of pork and paint generously with melted butter. Put 3 tablespoons butter in a cocotte over medium heat. When the butter is melted place the pheasant in the cocotte and reduce heat. Add salt and pepper. Cover and cook over low heat for 1 hour, basting with the melted fat. One-quarter hour before the pheasant is cooked, remove the pork fat and brown the pheasant in the fat on all sides. After placing the bird on its serving dish, add 1/3 cup brandy to the cocotte, scrape the bottom and sides of the cocotte to mix the glaze that will have adhered. Pour over pheasant and serve.

MUSSELS WITH A CREAM SAUCE (1)

Put in a fish kettle 2 quarts thoroughly scrubbed and washed mussels, 3 tablespoons butter, 3 chopped shallots, 1 clove of crushed garlic. Cover and over highest heat cook for 4 or 5 minutes. As soon as the shells open, the mussels are cooked. Drain the mussels. Strain the juice in which they are cooked through a fine hair sieve. Remove the mussels from the shells. Pour the juice into a bowl. There will be a deposit in the bowl. Be careful that it is not poured into the saucepan. Put saucepan over low heat, and when the juice is hot pour a small quantity of it into a bowl. Add 1/2 tablespoon saffron and mix well. Add this to the juice. Add 2 tablespoons flour, stir until the sauce has thickened, about 5 minutes. Add mussels. Reduce heat and slowly stir in 3/4 cup heavy cream. When it is quite hot remove to deep serving dish, sprinkle with chopped parsley and serve.

The mussels can be served cold with a

FENNEL SAUCE

made by adding 1 whole fennel cooked covered in boiling salted water for 3 minutes, removed from water, drained, pressed and wiped dry. Then chop very very fine and add to a Sauce Mousseline.

If one likes mussels at all one likes them madly, and that is the reason there are so many recipes for their preparation amongst the treasure. Here is another and last one:

MUSSELS WITH A CREAM SAUCE (2)

Put in a saucepan over medium heat 3 tablespoons butter. When it is melted, add 1 large carrot cut in thin slices. Reduce heat, cover and cook for 1/2 hour, shaking the saucepan from time to time. Then raise heat to high, add 3 quarts scrubbed and washed mussels, 1/4 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Cover and cook for 4 minutes. Remove mussels, drain and remove from shells. Put in a saucepan over medium heat 2 tablespoons butter and 1-1/4 cups chopped mushrooms. When they are hot, add 3 tablespoons flour. Stir with a wooden spoon. Add slowly the juice of the mussels which has been strained through a hair sieve. Stir with a wooden spoon. Boil for 4 minutes. Reduce heat and add 5 tablespoons butter and 1/2 cup heavy cream. Do not allow to boil and do not stir. Mix by tipping saucepan in all directions. Remove from flame; a few drops of lemon juice may be added, for those who care for it.

Most of the treasures in this collection are French and this is intentional. Though collecting began in the United States, my cooking days have been spent in France. There are however some Italian and Spanish treasures, which doubtless in the United States now belong to the public domain. But one Spanish recipe is tempting. It must be confessed it came to me from a French friend and is therefore unquestionably a modified version of the original. Chauvinism apart, how can one feel otherwise than that it has been contaminated through a natural prejudice. Here it is:

FISH IN A SPANISH PIE

Mix 1/2 cup olive oil, 1 egg, a pinch of salt, a good pinch of powdered anis, 1-1/2 tablespoons brandy. When thoroughly mixed, add 2-1/4 cups flour, work with a pastry blender but do not overwork. Add only enough water to hold the dough together. Put on a floured board, knead it out thin with the palm of the hand to about 1/2-inch thickness. Roll into a ball and repeat the rolling and kneading. Roll into a ball and put aside for several hours in a cool place (6 hours is recommended). The kneading must be done quickly. This amount of dough will be sufficient for a fish weighing 2 to 2-1/2 lbs. Spaniards prefer trout to other fish -- they consume an incredible amount of it. So a trout it should be, but any fish that hasn't too strong a flavour will do. After the fish is cleaned, cut open down the stomach side. If one is not butterfingered, but oilfingered, with a sharp knife the backbone can be removed. In any case the fish is rubbed inside with salt and powdered nutmeg, painted with olive oil and stuffed with hazel nuts and seedless raisins in equal quantity. The nuts are placed in the oven to brown lightly. This helps to remove the skins by rubbing them in a dishcloth while still hot. Be sure that no skin remains. It is very unpleasant to encounter. Tie the fish together. Roll out the dough, place the fish on it, moisten the edges of the dough. Cover the fish completely. Press the edges of the dough together and place fish in a fireproof serving dish in a 450 ͦ oven for 35 to 40 minutes. It is a delicious dish.

The French make their version of pumpkin pie. It is a country dish, Paris does not know it. In the Bugey for the vintage they make one as we do in the United States, except for the omission of nutmeg or cinnamon flavour and of currants. When we told this to the daughter of a farmer who brought us one she had baked, she said they didn't grow spices, it was not hot enough, and their grapes were not suitable for drying and becoming currants. When it was suggested that nutmeg and currants could be bought in Belley, she was aghast and said that they never, but never, bought any provisions except coffee and sugar.

This is a pumpkin pie, but not a sweet one. It is called

THE CITROUILLAT

Take 5 lbs. pumpkin, peel it and cut it into 2-inch cubes. Place them in a bowl in layers with a sprinkling of salt between each layer. Let stand overnight. The recipe given above for the crust of Fish in a Spanish Pie is suitable if butter replaces the oil and the anis is omitted. In the morning wipe the cubes of pumpkin, and when dry place in a flat ovenproof dish, cover with the dough. Leave a 1-inch hole in the centre. The French like to decorate the opening by placing around it leaves cut from the dough. Place in preheated 400 ͦ oven for 3/4 hour. When it is removed from oven put into the hole in the centre as much heavy cream as the pie will accept, about a cupful, if the pie is inclined in all directions.

I did not think that com meal was much used by the French but it is in the Jura, even in Burgundy. This is one of their recipes for a cake.

CORN-MEAL CAKE

(the French call it Croquants, which would he Crispies to Americans)

Mix thoroughly 1 cup corn meal, 2 cups flour and 1 cup sugar. Over very low flame slowly melt I cup butter and pour it over the dry ingredients. Mix thoroughly with the back of a spoon. Pat into a buttered pie plate with a detachable bottom. Place in a preheated 400° oven for 15 or 20 minutes. Be careful that it does not bum. It can be covered with a water icing to which 1 teaspoon rum has been added. Cut while hot.

And now for some recipes for desserts.

An English friend told me that her grand-aunt who was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria bought a camel-hair India shawl and wore it to go to the palace. To her everlasting shame, a label tag which had not been removed and which was plainly visible was read by one of the royal dukes: Chaste but Elegant. It is a suitable name for this dessert,

RICE WITH FRUIT

Put 2 cups well-washed rice in a saucepan of cold water over high flame. Bring to a boil over medium heat 4 cups milk, 1 cup sugar and the rice. As soon as it comes to a boil, remove and drain. Put under the cold-water tap and drain. Reduce heat to lowest flame. Put rice in 1 quart milk and simmer for I hour without stirring. Place an asbestos mat under the saucepan. When cooked, add 1 teaspoon rum and pour into lightly oiled ring mould (preferably oiled with sweet almond oil). When it is cold, turn out and chill. The centre is filled with sweetened whipped cream. Decorate with strawberries. Cover the rice and keep enough to fill a bowl with this sauce: equal parts of strawberries and raspberries mashed through a fine sieve sweetened with icing sugar and flavoured with juice of 1/2 lemon and 1 teaspoon rum.

How or when this next recipe came into the cook-book of a French family they were not able to say, but it was written in a handwriting they recognised as that of a great-grandmother. It is for

CREME MARQUISE

(Jean-Jacques Rousseau was underlined)

For three servings, melt 3 ozs. chocolate over hot water. When it is melted add in small quantities at a time 8 tablespoons butter. Stir continuously. Add the yolks of 3 eggs, one at a time, stirring in the same direction. Remove from heat and fold into the stiffly beaten whites of 3 eggs. Chill before serving. It is really an excellent version of a common French dessert.

This too is a recipe of a common dessert, but a very good one, for

EMPRESS RICE

Wash 1/2 cup and 1 tablespoon rice in several waters, then soak in cold water for 2 hours. Drain and put in a saucepan of boiling water. When the water reboils, remove rice after 2 minutes and put it into 2 cups boiling milk with 3/4 cup sugar and allow it to simmer over low flame for 3/4 hour. Boil 2 cups thin cream with 1/4 cup sugar. Stir yolks of 4 eggs, mix with hot cream. Stir with wooden spoon over lowest flame until spoon is coated with mixture. Remove from heat, add r tablespoon vanilla extract and stir occasionally until perfectly cold. Then add 1 cup whipped cream. Gently mix into the rice 1 cup thinly sliced mixed fruits -- bananas, berries, apricots and peaches that have been soaking in rum and in their juice, and 1/4 cup angelica cut in very small dice. Put into a lightly oiled mould in the refrigerator for at least 2 hours.

The French serve this dessert with a fruit or vanilla sauce, but perhaps we would prefer whipped cream.

An excellent ice cream is made with honey instead of sugar.

NOUGAT ICE CREAM

Heat 3 cups thin cream in saucepan over low heat. Stir 6 yolks of eggs and add the hot cream. Put over lowest heat and stir until spoon is coated. Remove from flame and stirring continuously pour it slowly over I cup honey (preferably orange flower). Add 1 tablespoon orange-flower water. Strain, and when cold incorporate 1-1/2 cups whipped cream and fold in 3 whites of eggs beaten stiff, 3/4 cup pistachio nuts that have been blanched, skinned and thoroughly dried, and 1/2 cup blanched almonds cut in half lengthwise (with the point of a knife they open very easily while still moist). Flavour with 1 tablespoon orange-flower water and freeze.

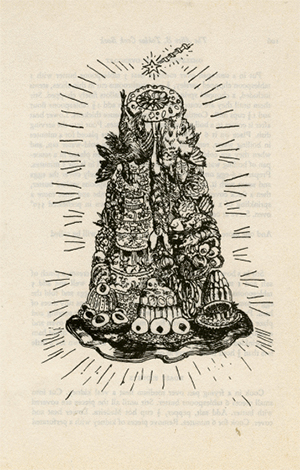

Here are four recipes, interesting at least for the names attached to them. To commence with one of Stephane Mallarme's in his own words. He calls it marmalade, but it is an incomparable dessert.

COCONUT MARMALADE

No one who has entered and taken up from a counter a coconut and bought it knows what to do with it. For Parisians this classic fruit from afar, amongst the pomegranates or oranges and pineapples, remains a useless curiosity. But here is one of the most delicate dainties, of which it is the principal ingredient, from the islands and their coasts. Put 2 cups sugar and 1/2 cup water in a copper kettle and boil until it comes to the little pearl, drop in the grated coconut and stir with a wooden spatula. After 15 minutes, put 2 eggs into another kettle, pour the coconut into it, stirring in the same direction. Flavour with vanilla, cinnamon or orange-flower water, return to the fire for 5 minutes, and after letting it cool for 5 minutes pour it into a compotier (fruit dish) and serve cold.

It is indeed a delicate dainty as the poet describes it, but the syrup must not cook for as long a time as his recipe advised. My dessert was an excellent candy resembling a Chinese sweet long before it was time to add the yolks of eggs. So now it is made with I cup water and boiled to 220°.

This is a

CUSTARD JOSEPHINE BAKER

Beat 3 eggs with 3 tablespoons sugar. Mix 2 tablespoons flour in a little milk and add 2 cups more milk. Mix with sugar-and-egg mixture and strain. Add 2 teaspoons kirsch and 3 tablespoons liqueur Raspail. Add 3 bananas cut in thin slices and a few tiny pieces of the zest or rind of a lemon. Mix well, pour into a fireproof dish and cook in preheated 400° oven for 20 minutes. Serve cold.

Raspail is a liqueur for which it will probably be necessary to substitute another.

Rossini, who was inordinately fond of truffles, created this salad, but only after Alexandre Dumas, junior, had put before the public a better version of it.

ROSSINI'S SALAD

Four parts boiled sliced potatoes and one part sliced truffles that have been cooked in champagne and are served with the usual vinaigrette dressing of three parts olive oil, one part vinegar, salt and pepper.

And here is the proof that the master is greater than the follower:

ALEXANDRE DUMAS JUNIOR'S FRANCILLON SALAD

This is the recipe as he gives it in his play Francillon, first produced at the Comedie Francaise.

ANNETTE: Cook some potatoes in bouillon, cut them in slices as for an ordinary salad, and while they are still warm season them with salt, pepper and a very good fruity olive oil, vinegar ....

HENRI: Tarragon?

ANNETTE: Orleans is better, but that is not of great importance. What is important is a half glass of white wine, Chateau Yquem if it is possible. A great deal of herbs finely chopped. At the same time, cook very large mussels in a court-Bouillon with a stalk of celery; drain them well and add them to the potatoes.

HENRI: Less mussels than potatoes?

ANNETTE: A third less. One should taste the mussels little by little. One should not foretaste them, nor should they obtrude. When the salad is finished, lightly turned, cover it with round slices of truffles; a real calotte (or crown) for the connoisseur.

HENRI: And cooked in champagne?

ANNETTE: That goes without saying. All this, two hours before dinner, so that the salad is very cold when it is served.

HENRI: One could surround the salad with ice.

ANNETTE: No, no, no. It must not be roughly treated; it is very delicate and all its flavours need to be quietly combined.

It is a combination that is exquisitely and typically a French one. Why it is more popularly known as Japanese Salad no one has been able to tell me.

The proportions for it as made today are -- 2 lbs. potatoes, 3 quarts mussels, truffles -- as many as the budget permits -- 3/4 cup olive oil, 4 tablespoons vinegar, 1 tablespoon herbs, 1/4 teaspoon peppers, little salt (the mussels are salty), 4 cups bouillon and 1 stalk of celery.

_______________

Notes:1. Roselio is a Catalan liqueur or cordial which is also made round about Perpignan. It has not been imported into England since the war: Grenadine might replace it.