Jeffrey Epstein, My Very, Very Sick Pal. A very weird interview with Stuart Pivar about Epstein, his science parties, his “pathology,” and the industrial scale of it all.by Leland Nally

Mother Jones

August 23, 2019

https://www.motherjones.com/criminal-ju ... -sick-pal/NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Stuart Pivar, 89 years old, is an art collector and a controversial scientist who says Jeffrey Epstein was his “best pal for decades” until the two fell out, he told me, over allegations of Epstein’s sexual misconduct. Still, when we spoke last week, Pivar was in mourning for his old friend, who days earlier had killed himself in jail while awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges. Pivar was angry, too, with the shallow coverage of the Epstein case. “Jeffrey was profoundly sick,” he said, ascribing Epstein’s sexual compulsions to a case of satyriasis.

Pivar, an industrialist who made his money in plastics, acted as a sort of art consultant to Epstein. In 1982 Pivar helped found the New York Academy of Art alongside Andy Warhol; Epstein would later serve on the academy’s board, which is how he came to meet, in 1995, an aspiring artist named Maria Farmer, who was 25 at the time. In an affidavit filed in April, Farmer said she and her 15-year-old sister were sexually assaulted by Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell, the British socialite accused of soliciting young girls on Epstein’s behalf. (Maxwell has repeatedly denied accusations of sexual abuse and sex trafficking.)

Pivar was also present for a number of Epstein’s science summits. Epstein himself was no scientist, said Pivar, the author of Lifecode: The Theory of Biological Self-Organization and an advocate of non-Darwinian models of evolution. (This was borne out in a recent New York Times story that described Epstein’s interest in cryonics and eugenics and his wish to “seed the human race with his DNA by impregnating women” at his New Mexico ranch.) Epstein was a dilettante, and easily distracted. But he pulled so many prominent thinkers into his social circle, using the promise of his money to create “some kind of a mini university of thought,” that in Pivar’s view he did “amazing, incredible, amazing, remarkable things for science.” There were lavish dinner parties with the likes of Steven Pinker and Stephen Jay Gould during which Epstein would ask provocatively elementary questions like “What is gravity?” If the conversation drifted beyond his interests, Epstein was known to interrupt, “What does that got to do with pussy?!”

Pivar was close enough to Epstein that the financier put him “in charge of Ghislaine while she was profoundly depressed from the death of her father,” the media mogul Robert Maxwell. Despite their friendship, Pivar said, he was “insulated” from the lurid aspects of Epstein’s personal life. “I don’t know anything about that,” he said, “because I was never invited to the Isle of Babes,” Epstein’s private island in the Caribbean.

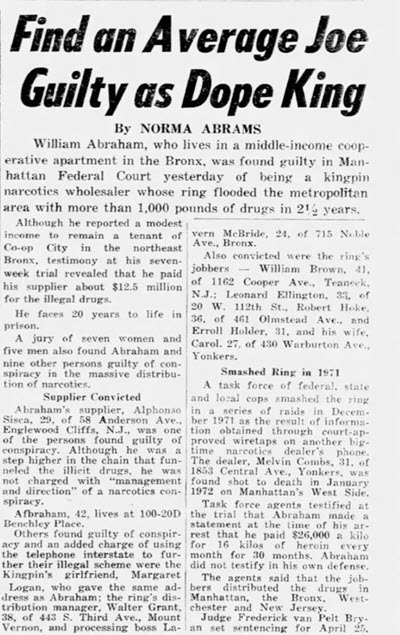

In his telling, Pivar ended his friendship with Epstein after learning from Farmer of her sexual assault. Some evidence of the tension between Pivar and Epstein is lying in public view. In August 2007, Pivar sued a science blogger named P.Z. Myers and Seed Media Group, which hosted his blog, alleging defamation. Myers had lit into Pivar’s work, calling him “a classic crackpot.” In his complaint, Pivar made a point of mentioning by name two prominent members of SMG’s board: Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. The lawsuit was later dropped.

Pivar and I spoke by phone last week, a bizarre but occasionally illuminating exchange that ended with a half-joshing threat to sue me. The conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. I’m a writer doing a story on Jeffrey Epstein. I was wondering if maybe you wanted to talk, if you had any interactions with him or ever met him?

A. Jeffrey who?

Q. Jeffrey Epstein.

A. Oh, that Jeffrey. Oh, I’ve heard of him. [Laughs] Who are you?

Q. I’m writing for Mother Jones right now—

A. Mother Jones. That is some kind of uh—

Q. It’s a publication, a political magazine.

A. I’ve heard of it, from way back, right?

Q. Yeah, they’ve been around since the ’70s. The reason I’m calling is because you were listed as a contact in his contact book.

A. I was? Oh, I thought he knew my telephone number by heart.

Q. Oh, really? So you did know him well?

A. Jeffrey Epstein was my best pal for decades.Q. Really?

A. Yeah. Jeff, I adored him.

Q. How did you guys meet?

A. One day in the early ’70s a friend of mine brought me to Jimmy Goldsmith’s mansion on the east side. And I walked in, and there in the grandiose lobby was a grand piano, and there was somebody playing the piano with great virtuosity. And it was Jeffrey Epstein. That’s how I met him. Did you know that Jeffrey was a piano virtuoso?Q. I heard that he played the piano. I never heard the word “virtuoso.”

A. Yeah, he was a major talent, among his other talents.

Q. So you guys were friends since then?

A. For a very long time. Daily pals.Q. So I’ve got to ask right off the bat: What’s your take about the current scandal? The allegations?

A. Listen, I’m in mourning for Jeffrey.

Q. I understand.

A. The way he died is very immaterial.

Q. Do you think he would be the type of person to take his own life?

A. Those kind of things are trivia to me, with respect to Jeffrey and what he was and all that kind of stuff. That’s not the issue.

Q. I understand.

A. That’s not of any interest, really. Jeffrey was an important person. The detail of he happened to kill himself is completely immaterial and profoundly sad.

Q. What do you think you know about Jeffrey that the broader public might not know? You know, about who he is as a person?

A. Everything, everything, everything.Q. Okay. Would you ever like to talk in more detail about your relationship with him?

A. What do you want to know?

Q. Well, he’s obviously at the center of a lot of attention right now.

A. No kidding.

Q. The allegations are very severe. They’re very alarming. And it’s—

A. No kidding. But they’re totally, totally, totally, totally misunderstood.Q. So you don’t think he’s guilty of any of the allegations against him right now?

A. Let’s put it this way. What’s the difference between the punishment which befalls a murderer and a serial murderer? It’s the same. If Jeffrey Epstein was found guilty of fooling around with one

16-year-old trollop, nobody would pay any attention. The trouble is,

what he did was quantitative and not qualitative.What Jeffrey did is nothing in comparison to the rapes and the forceful things, which people did. Jeffrey had to do with

a bunch of women who were totally complicit. For years, they went,

came there time and time and time again. And if there was only one of them who did it, no one would have noticed—except

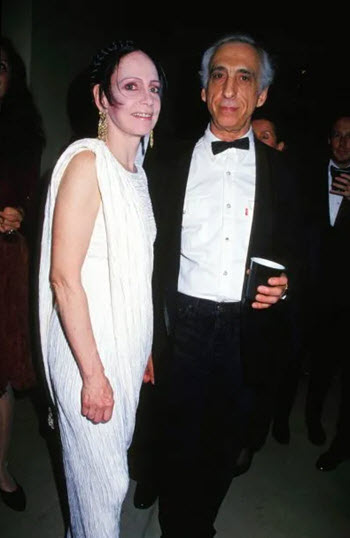

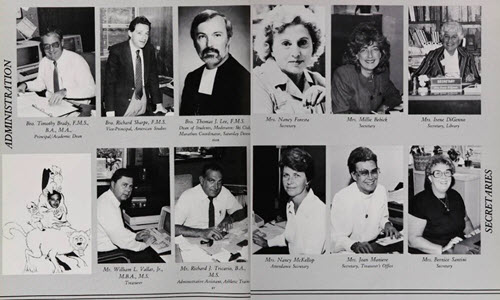

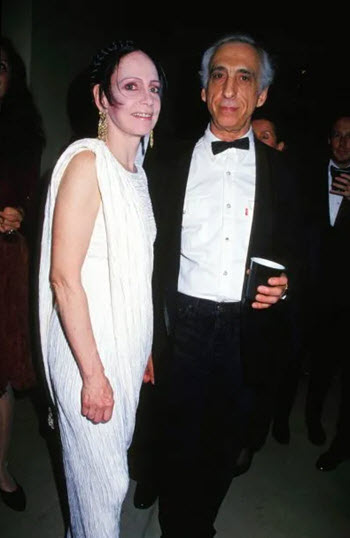

he made an industry out of it. And why did he make an industry out of it? Because Jeffrey was a very, very, very sick man. For some reason that doesn’t get understood. Did you ever hear of nymphomania? Do you know what that is? Stuart Pivar with Mary McFadden at the opening of the Andy Warhol Museum in 1994. Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

Stuart Pivar with Mary McFadden at the opening of the Andy Warhol Museum in 1994. Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.comQ. Vaguely, yes.

A. What do you mean “vaguely”? Everybody knows what a nymphomaniac is.

It’s a girl who is insatiable in her sexual appetite, right?

Q. Yes.

A. Yeah. There are men who are like that, and

it’s a disease. It’s called satyriasis, and Jeffrey was afflicted with that.

Some pocket-size books express nothing but the pornography of violence, which derives from crime comics directly or indirectly....

Here is one endorsed by an "Internationally Famed Psychiatrist." The endorsement says that this book also is an "educational experience," that it shows a disease "medically known as satyriasis ... based on one or more emotional traumas occurring in early life" and that such a person "will stop at nothing to gain his ends, not even murder." (Even medically that is entirely false.) In this book, girls are murdered, but the high point here is when the hero beats the heroine. She "enjoys the blows." "It was like the time she had watched the Negro being beaten and stoned and what she had felt then she was experiencing again." Sadism (or masochism) as sexual fulfillment -- that is the "educational experience" in these books.-- Seduction of the Innocent, by Fredric Wertham, M.D.

The most horrible execution, perhaps of all time, was that of unfortunate Robert François Damiens who made an attempt on the life of Louis XV and on March 21 of that year was tortured to death. Thomas Carlyle in his The French Revolution cries out: "Ah, the eternal stars look down as if shedding tears of compassion down on the unfortunate people." We believe that a thousand executions by the guillotine cannot balance the terrible execution such as that of poor Damiens, who merited the sympathy of heaven and the stars. This shameful deed of the ancien régime could not have been washed away by all the blood that fell during the Revolution.

And when the individual details are given, the cruelty in Marquis de Sade's works seems entirely conceivable and heralds the passionate bloodthirstiness of the Revolution.

We possess the following account of the execution of Damiens by an eyewitness, de Croy, which we follow in the main. The same judgment was carried out on Damiens as on the murderer of Henry IV, François Ravaillac, on May 27, 1610. On the morning of March 28, 1757 Damiens was put on the rack; with glowing hot forceps his breasts, arms, legs and calves were torn out and in the wounds were poured molten lead, boiling oil, burning pitch mixed with red hot wax and sulphur. At three o'clock in the afternoon the victim was first brought to Notre Dame and then to the Place de Grève. All the streets that he had to pass by were packed with people who showed "neither hate nor pity." Charles Manselet reported: "Wherever one turns one's eyes one sees only crowds in Rue de la Tannerie! The crowds at the intersection of Rue de I'Épine and Rue de Mouton! The crowds in every part of the Place de Grève. The court itself was a compact mass, consisting of all possible classes, particularly the rabble."

At half past four that dreadful spectacle began. In the middle of the court was a low platform upon which the victim, who showed neither fear nor wonder but asked only for a quick death, was bound fast with iron rings by the six executioners so that his body was completely bound. Thereupon his right hand was extended and was placed in a sulphurous fire; the poor fellow let loose a dreadful outcry. According to Manselet, while his hair was burning, they stood on end. Thereupon his body was again attacked with glowing tongs and pieces of flesh were ripped from his bosom, thighs and other parts; molten lead and boiling oil were again spilled on the fresh wounds, the resulting stench (declared Richelieu in his Memoirs), infected the air of the entire court. Then four horses on the four sides of the platforms pulled hard on the heavy cables bound to his arms, shoulders, hands and feet. The horses were spurred on so that they might pull the victim apart. But they were unused to acting as the handmaids of executioners. For more than a hour they were beaten to strain away so that they might tear off the legs or arms of the victim. Only the wailing cries of pain informed the "prodigious number of spectators" of the unbelievable sufferings that a human creature had to endure. The horses now increased to six, were again whipped and forced to jerk away at the cables. The cries of Damiens increased to a maniacal roaring. And again the horses failed. Finally the executioner received permission from the judges to lighten the horrible task of the horses by cutting off the chains. First the hips were freed. The victim "turned his head to see what was happening," he did not cry but only turned close to the crucifix which was held out to him and kissed it while the two father-confessors spoke to him. At last after one and one-half hours of this "unparalleled suffering" the left leg was torn off. The people clapped their hands in applause! The victim betrayed only "curiosity and indifference." But when the other leg was torn off he started anew his wailing. After the chains on his shoulders had been cut off his right arm was the first to go. His cries became weaker and his head began to totter. When the left arm was ripped off the head fell backwards. So there was only left a trembling rump that was still alive and a head whose hair had suddenly become white. He still lived! As the hair was cut off and his legs and hands collected and dropped into a basket, the father-confessors stepped up to the remainder of Damiens. But Henry Sanson, the executioner, held them back and told them that Damiens had just drawn his last breath. "The fact is" wrote trustworthy Rétif, "that I saw the body still move about and the lower jaw move up and down as if he wanted to speak." The rump still breathed! His eyes turned to the spectators. It is not reported if the people clapped their hands a second time. At any rate during the length of the entire execution none moved from their places in the court or from the windows of adjoining buildings. The remainder of this martyr was burnt at a stake and the ashes strewn to the four winds. "Such was the end of that poor unfortunate who it may well be believed—suffered the greatest tortures that a human being has ever been called upon to endure." So concluded the Duke de Croy, an eyewitness, whose report we have almost literally translated. We will give a few more accounts by eyewitnesses of that fateful day when an entire populace greedily waited through few hours for the most dreadful tortures that the world had ever seen.

"The assemblage of people in Paris at this execution was unbelievable. The citizen of near and far provinces, even foreigners, came for the festival. The windows, roofs, streets were packed head on head. Most surprising of all was the dreadful impatient curiosity of women who strained for closer views of the torturings." Madame du Hausset tells in her memoirs that gambling went on during the execution and that wagers were made on the length of the duration of the tortures by Damiens.

Casanova, one of those who came from a foreign country to see the execution, reported a scene that was an excellent if terrible example of the theory of de Sade, that the tortures of another spur on real pleasure. He writes: "On March 28, the day of the Martyrdom of Damiens, I called for the ladies at Lambertini's and since the carriage could scarcely hold us all, I placed my charming friend on my lap without much difficulty and so amused ourselves until we came to the Place de Grève. The three ladies pressed as close to each other as they could so that they could all look through the window. They rested on their arms so we could see over their heads.

"We had the patience to maintain our uncomfortable position for four hours of this horrible spectacle. The execution of Damiens is too well-known for me to write about it. Also because the description would take too long and because nature revolts at such atrocities. During the execution of this sacrifice of the jesuits (his execution was said to have been done by order of the jesuits), I had to turn my eyes and hold my ears so that I might not hear that heart-rending cry when he had but half of his body. But Lambertini and her old friend made not the slightest movement; was that because of the cruelty of their souls? I had to pretend that I believed them when they said that his crime had prevented them from feeling sympathy for his plight. The fact is that Tiretta occupied herself during the execution in a most peculiar manner. She lifted her skirt high because, she said, she didn't want it dirtied. And her friend obliged her in the same way. Their hands were busily engaged during all the tortures."

Commentaries to Casanova's account are superfluous. That it was not an isolated case of satyriasis but one of the phases accompanying the horrible execution and calling forth passionate ecstasies was shown clearly by the fact that this charming sexual maneuver lasted two hours as expressly mentioned by Casanova later. "The action was repeated and without a resistance.” That Louis XV told the embassies all the details of the execution with great satisfaction is not strange. The execution of the poisoner Desrues who, on May 6, 1772, was placed on the wheel and then burnt alive, was also "well attended by a distinguished crowd."

-- Marquis De Sade: His Life and Work, by Dr. Iwan Bloch, 1889

I see.

He couldn’t help himself.

And this is something—

I know that.

This is something that you observed with him personally, as his friend?

At close range.

You saw him struggle with this?

Yeah.

Was it a struggle for him? Did he ever—

I wouldn’t say struggle. He didn’t struggle with it. He was in a position financially to yield to it, big time. But nevertheless, he could not help himself. I’ve seen him do things which he couldn’t—couldn’t help himself, he was afflicted with it. If he had tuberculosis it wouldn’t be called a perversion, would it? Because he coughed too much?

Right. So you’re not disputing whether he did these actions or not?

I know what he did except I know the cause of it and other people simply can’t conceive of the idea that what Jeffrey did—that he was beset with a pathology, like a disease. I watched it happen.

So were you ever around for any instances of these?

Of course! No, I never saw him fool around with—in fact, Jeffrey was a very, very close friend of mine. And he shielded me. I never saw what he did until finally I did notice certain things, and that was the end of me having to do with him. But for a very long time, for years and years and years, Jeffrey did amazing, incredible, amazing, remarkable things for science and all kinds of stuff. He was a very, very good friend to me.

He never invited me to the “Isle of Babes,” luckily. I never knew it was even there.

Really? So you ended your relationship? You said when—

Well, I ended my relationship when I began to realize that he was doing things that I didn’t know about.

What were some of those things—

One day at the flea market there was Maria Farmer there, and I said, “What are you doing here?” And she told me this bizarre story, and then Jeffrey shows up, and I realized oh my god something was happening after years and years, which he didn’t tell me.

He was very scrupulous about leaving me out of that stuff. He never invited me to the Isle of Babes.

[Editor’s note: Attempts to reach Farmer were unsuccessful.]

So you never went there or anything like that?

No, of course I didn’t. For a while I was annoyed that he didn’t invite me. ’Cause all kinds of—see, I was involved in his scientific affairs.

I see. So—

I’m a scientist, and I saw all the incredible, wonderful things he did for science, which nobody’s managed to have the intellect to understand.

Right. Interesting.

Damn right, it’s interesting.

What were some of the signs that led you to end your relationship with him?

I told you.

So that was the main one, Maria Farmer, who you saw when—

Right, when one day at the flea market there’s Maria Farmer, who I knew ’cause she was a student at the New York Academy of Art, and I [asked], “What are you doing here?” And she started to tell me about some terrible thing, too terrible to utter, having to do with Jeffrey Epstein. And then a minute later, he shows up. And I began to put two and two together. And I realized that something was going on, which I didn’t know about. And at that point, I knew that he had a different life that I was not aware of.

The press coverage of this—what Jeffrey did was quantitative, not qualitative.

So what you’re saying—

Anyone who did one thing, let us say, to some 16-year-old trollop who would come to his house time after time after time and then afterwards bitch about it— why, no one would pay attention. Except Jeffrey made an industry out of it.

When you say he made an industry out of it—

Apparently he went beyond. This got out of hand. What’s the name of that girl? I forget. Time after time after time after time she comes there for I don’t know what length of time, and then after it’s all done, she has things to say—why did you stay there? In other words, what I’m saying is, what Jeffrey did in comparison with other people is only different in the fact that he made an industry out of it.

And when you say industry, do you mean bringing—

Industry! He did stuff with underage girls who knew what the hell they were doing. By the hundreds. If he only did one, no one would pay attention. Nor, on the other hand, did he actually rape any of them or anything like that, which happens, you know. If you want to make a list of, let us say, in the past several years, of the kind of stuff going on of sexual abuse of children and what the hell not—you want to compare that with what Jeffrey did? What Jeffrey did in comparison with the kind of stuff which gets exposed every day of people who are abusing children left and right and all kinds of institutions? Jeffrey never did anything like that. Everything he had to do with these girls was complicit. And it was just interesting to the rest of the world who doesn’t understand that Jeffrey was a very sick man. He had a case of what is called satyriasis. Did you hear of that?

No, I haven’t, actually. First time.

Let me elucidate you then. You ever hear of nymphomania?

Yes.

That’s girls who can’t, who are, how would you describe it? Nymphomania is a known sexual aberration, which is described scientifically in works on that subject. Another subject is called satyriasis. This is men who are afflicted with a similar—I hate to use the word “perversion,” because what does “perversion” mean? Perversion is, I mean, there are pathologies of all kinds. People get sick and do all kinds of weird things. Some of them are called perversions because they’re peculiar.

And you think Jeffrey had a perversion?

Jeffrey was ill. Jeffrey was born with a case of satyriasis. Somebody like you, incidentally, who wants to be writing on the subject, should know a thing like that.

Okay. This is the first time I’ve heard it in connection with him.

What do you mean? Isn’t it quite obvious that Jeffrey was pathological?

There are plenty of people with satyriasis like there are plenty of nymphomaniacs, except very few of them have the money to, let us say, treat themselves to sex three times a day with young girls. That was what he had to do. Other people, there are plenty of cases, presumably, if you want to read up on the subject—it’s called satyriasis, right? It’s the male version of—did you ever meet a nymphomaniac?

No, but I understand the concept.

Do you know what a nymphomaniac is?

Yeah.

These are many women who are possessed with an uncontrollable need for sex. I actually once sort of knew one, as a matter of fact. She told me she was abused by her father. And as a result of this, the poor thing had an uncontrollable need for sex to the point that it was embarrassing. She was what’s called a nymphomaniac.

You told me you heard something terrible that Maria told you.

Jeffrey brought her there, and what he did to Maria was inexcusable, of course. He locked her up, and she couldn’t get away, and her father had to come and rescue her. That’s a story she told. And, of course, that’s the least of what she told me. Forget that, her little sister, for Christ’s sake, the guy actually brought her to his place and did those kind of things, which, of course, is inexcusable and that’s the kind of thing which satyriasists do because they can’t help themselves.

And this is Maria Farmer you’re talking about, who you knew? How’d you know her?

She was a student at the New York Academy of Art. Jeffrey was on the board of trustees of the New York Academy of Art. That’s how come he knew her.

How do you think they met?

Jeffrey used to go to the functions of that institution. She was there. She was an artist, and Jeffrey used to buy drawings and what the heck not. My guess is that he was there only for the purpose of meeting…it wouldn’t surprise me.

So this was when you started to—

The story of Maria Farmer and her sister is already in print. You don’t need me to tell you that, and if you don’t know it, you’re not qualified to write this story.

No, I understand. But it’s interesting hearing it from your perspective. You had a really interesting moment, to hear that directly from her.

I saw that he did that, and I was horrified. It was the last I ever saw of the guy.

So you believed her when she told you that story?

Well, of course!

And were there any other moments like that where you became aware of things Jeffrey was doing—

Yes, yes, yes.

Would you care to share any of those details?

Yeah, one time—the point is, Jeffrey was a sick man. Like people are sick with all kinds of diseases of every kind, especially behavioral ones. There are all kind of nuts running around. They get guns, and they kill people and all that kind of stuff, due to behavioral aberrations.

It’s interesting to hear from someone who knew Jeffrey Epstein—

I knew him quite well, for years and years and years and years and years.

—who is bringing this perspective that he was a sick individual, that he couldn’t help himself.

I observed that Jeffrey Epstein was a very important person in the scientific world. Jeffrey brought to science something which nobody else did.

What was that?

He brought together scientists for the sake of trying to inculcate some kind of a higher level of scientific thought, even though he himself didn’t know shit from Shinola about science.

He never knew nothing about anything. Nevertheless—

How do you think he got so successful if he didn’t know anything? That’s one big question around Jeffrey Epstein—

No, no, no, he didn’t know anything about science.

Okay.

He knew plenty about how to make money.

What were some of his passions in science? What did he talk to you about in the realm of science?

Jeffrey—how to put this? Jeffrey came into the concept of thought and science and all with no knowledge whatsoever about anything. He really didn’t know a goddamn thing. I don’t even believe that he taught math. I can’t—oh, Jeffrey once told me that he studied math with the Unabomber. Did you know that?

Really?

Yeah. Jeffrey told me that he studied math at UCLA with the Unabomber, who was a math teacher.

Wow, that’s interesting.

That’s what he says, I don’t know. You might want to track that down.

But Jeffrey didn’t know anything about science. Nevertheless, in his peculiarly inquiring mind, let’s say, like a child who is fresh to the world—because he has no compunction about approaching people—he brought together the most important scientists like Stephen Gould, like Pinker, like all of those people, and myself even, at dinners, and would propose interesting, naive ideas. Steve Pinker describes that. He would say, “Oh, what is gravity?” Which of course is an unanswerable thing to present at a dinner to a bunch of scientists. And because he was Jeffrey, why, they would—and as the founder of the feast—they would listen to him and try to give [answers]. He was attempting, somehow, in his ignorant and scientifically naive state, to do something scientifically important. He had no compunctions about inviting people, and since he had money, they would listen. He would promise money to people and, of course, never come across, by the way. That’s what’s called a dangler. Didn’t he promise $15 million to Harvard? I don’t know if they got two cents.

So people would come to his dinners, including myself. I even had them. Take a look at Steven Pinker’s essay. Jeffrey brought these people together and thought that he was causing basic thought processes to happen, which he sort of was, even though they were sort of irrelevant. I mean, to bring together a bunch of scientists and say, what is gravity? Which is ridiculous in a way, even though it’s a question nobody can answer. But he would do that kind of stuff. Just for the sake of, I don’t know what. And Jaron Lanier and all that group, the greatest thinkers that they were, he brought together with a purpose of thinking, rightfully or wrongfully, that he was going to introduce some kind of logic or something—some special kind of a thought process, which others hadn’t thought of, which of course is absurd.

While everybody was watching, we began to realize he didn’t know what he was talking about. Then after a couple of minutes—Jeffrey had no attention span whatsoever—he would interrupt the conversation and change it and say things like, “What does that got to do with pussy?!”

Really?

That was his favorite expression. It was a subject changer. And it revealed what was really in his mind. Of course, that was the only thing that was going on in his mind. The poor guy had—it’s hard to, you can’t describe Jeffrey. And because he had dough, he was able to realize the weirdest situations, which he would convoke by bringing brilliant people together and proposing silly ideas at dinner, and everyone would listen because he was handing out dough. And it was an indescribable situation—trying to create some kind of a mini university of thought while he himself knew zero.

You said he brought up these crazy ideas. Can you remember any of his own ideas?

He would propose the fundamental questions of science. What’s up? And what’s down? And what’s gravity? And then when I knew him at the very, very beginning, before he was Jeffrey—I knew Jeffrey before he was Jeffrey.

And when he brought Ghislaine [Maxwell] to this country, he put me in charge of her because she was a total wreck. It was my job to try to amuse her.

And that was when you first met Jeffrey, he handed her off to you because—

No, that was much later. I knew Jeffrey a long time before that. But when she arrived, after her father jumped off the boat or whatever happened, she was a total wreck. And my job was to amuse her, take her to dinner and lunch and what have you until she finally came around, and then was okay.

When I watched this happen, I had no idea what the hell it was all about. And the idea that no one has recognized that Jeffrey was profoundly sick, with a male counterpart of nymphomania, which he could not control…

What was his relationship to—

Look, it wouldn’t surprise me—probably a lot of men have that for all I know. But none of them have the dough to have underage girls three times a day to work it out. So instead, God knows what they do. The peculiar thing is, let’s put it this way, now that you’ve got me thinking: Jeffrey had a severe case of what’s called satyriasis, the male counterpart of nymphomania. Except that he had the money and the wherewithal to work it out, to manage to supply himself with three underage girls every single day.

Who knows how many men have that? And the difference is that if there are other ones who have it, I don’t know, they probably go around raping or God knows what they do. Jeffrey had the money to do it politely—namely, by getting complaisant young girls.

Now what was his relationship like to Maxwell? Because you knew them both.

It annoys me that that the whole thing is dealt with so superficially. Why doesn’t somebody talk to a psychologist?

For example, I was a sort of an art consultant, furnishing his numerous houses, and at one point I took him to a very prominent art dealer to buy furniture and what have you. I brought along an assistant I had who was a very attractive young girl, and there we were in those precincts of art and Renaissance furniture and what have you. He grabbed her up from behind and lifted her up and squeezed the hell out of her and she screamed. I said, “Jeffrey put her down! What are you doing?”

And the three or four of us who were watching were horrified, and he put her down. He was out of control. Have you ever seen anyone do a thing like that?

No, never. Where were you guys when he did that?

As a matter of fact, it was at the gallery of Ruth Blumka.

Ruth is dead now. But the point is, I saw Jeffrey do a thing I’d never seen in my life anyone do. And when I saw him do that, I said, oh my god. This is a screw loose. To do an uncontrollable thing like that.

Was there anything else like that? You mentioned him interrupting, talking about pussy at scientific dinners and—

You need to talk to Steven Pinker, who characterizes very well what Jeffrey’s mind was, how he couldn’t concentrate on a subject for more than two minutes before having to change the subject because he didn’t know what anyone was talking about and would blurt out the dumbest things.

Jeffrey is being dealt with as—the word “pervert” comes up. What’s a pervert? There are all kinds of behavioristic aberrations, obviously, including mass murderers. You don’t call mass murderers “perverts,” do you? “Perversion” is a word which is restricted, I suppose, to a certain kind of behavioral aberration having to do with sex. But the guy had this incredible sickness. You put that together with somebody with the kind of dough to pursue it, big time…

And you said he made an industry out of this. Do you know of any other people that Jeffrey knew that took part?

No of course not. Do you? Nobody—there was only one, only, only Jeffrey.

Okay, so you don’t think he roped anyone else into this or any of his friends or colleagues or whatever took part in these parties where these kinds of things would happen?

I don’t know anything about that because I was never invited to the Isle of Babes.

And you never heard anything? You never heard stories secondhand?

No. I didn’t even know it existed because Jeffrey insulated me from it.

What do you think about the allegations around that this was sort of a pedophile ring that had a very large scope, that had lots of people involved. Do you see that as a possibility?

Jeffrey had lots and lots and lots of dough. Scientists are always looking for lots and lots of dough, because most scientists spend most of their time writing grant proposals to raise money. Jeffrey didn’t require a grant proposal. Jeffrey would promise money and so they crowded around, and he also was an extremely personable, amusing kind of person to talk to. He was full of incredible ideas. He was charming in the extreme, and that’s why everyone paid attention to him.

You said he’s full of incredible ideas. What kind of ideas do you remember of Jeffrey’s?

He used to come up with all kinds of interesting—it’s hard to even put my finger on it. Haven’t you spoken to the other scientists who went to his various dinners? Or else went down to the Isle of Babes, which I did not do, and have them describe to you how come he was so fascinating? He is a very, very brilliant guy and has a very—how should I say—charming way of expressing himself, which everybody knows. And on top of that, promising all kinds of dough to scientists who were starving to get funded is a powerful combination. So they all listened. And of course, some of them may or may not have succumbed to whatever the hell they did down there at the Isle of Babes, ’cause I don’t know.

Sure, but you didn’t know of anyone who took part in the stuff that Jeffrey was doing on that island?

I knew perfectly well—I knew the people involved. But I didn’t know that they were doing, that they were—I didn’t know if or whether they partook in those kinds of things. Jeffrey used to appoint me in charge of Ghislaine while she was profoundly depressed from the death of her father. And other people, he would introduce me to wives of some of them and all that, I had no idea why that was. Jeffrey had numerous residences. And he used to rely on me to help him furnish them with art. I was sort of his art consultant, you might say, not that he ever took my advice. Because he pretended to be interested in art, but he was really more interested with—Jeffrey was so perverse. “Perverse,” that word, haha. You have to use it. What is perversion? You want to examine that.

Jeffrey was amused to have in his house fake art which looked like real art. Because of the fact that he was putting one over, so to speak. He thought that he was—how do you describe that? When you walked into this house, for example, there was a Max Weber or something like that, and it was a fake. And it amused him that people didn’t realize that. He was able to furnish his house with the fake paintings. Jeffrey had a collection of underage Rodins, for example, because what difference does it make if it’s real or not real? And if the real one costs nothing and the expensive one—it doesn’t make a difference. He was amused to put one over on the world by having fake art. He thought that he was seeing through the fallacy.

So would you say this was a pattern with him, that he would sort of pretend to be interested in science and pretend to be interested in art, but it was really all surface level?

Yeah. Let’s put it that way.

And in your perspective, is the reason for that—

You know, I just realized something. Why the hell am I talking to you and getting involved with Jeffrey Epstein when I shouldn’t? I regret everything I just told you, by the way.

Oh god, when journalists talk you’re supposed to not talk to them. Now, I’ve told you those interesting things, and they are interesting things. And, you know—by the way, is he going to have a funeral? Is there going to be a eulogy?

I imagine so.

Hey, why don’t you find that out? That’ll be interesting.

Would you attend?

Why don’t you try to find out if there’s going to be a funeral for Jeffrey or the eulogy or something like that.

I will do that.

In other words, the Jeffrey thing is profoundly deep, and all we see is a superficial thing. While underneath it is a kind of human aberration, which should be interesting to science rather than to trivial journalism. And sensational journalism. No one is paying attention to what he was afflicted with, with the possibility that other people are afflicted with it, too, and don’t have the money to do it quantitatively like he did. Who knows what lurks out there? How many Jeffreys are there—who don’t have the dough to do what he does, but instead do whatever the hell they do? Who examines sex crimes to determine if they’re really cases of Jeffreyism?

There’s so much there. It is a disgrace to science that what afflicted Jeffrey is not being investigated.

So that’s what you wish people knew about Jeffrey?

I’m saying this to you, that it’s a disgrace to science that what afflicted Jeffrey is not being discussed scientifically, in the event that there are plenty other Jeffreys who don’t have money. It’s an interesting question.

The business of sexual attraction, the attraction of males and females in its natural state, is not the same as what happens when civilization puts [up] all kinds of rules. Because sexual attraction starts at a very, very young age. When I was 14, I had to deal with a girl who was only 13. And somehow, I remember, it was at summer camp. And I stopped having to do with her because of the tremendous age gap. Girls at the age of 12, 13, and 14 have sexual attraction to 14- and 15-year-olds. But it’s not supposed to be that way. And so, all kinds of rules get made. And nature is not allowed to take its course on account of civilization. Jeffrey broke those rules, big time. But what he was pursuing was the kind of, I suppose, sexual urges which would—why am I telling you this stuff for? Leave me alone. Go away.

This is all very interesting—

I know it’s very interesting, but I’m just realizing something. I have just gotten myself into terrible trouble and everyone who knows is going to be mad at me—why the hell did I pick up the phone?

I appreciate you giving me your perspective on this. And—

No, you don’t. You’re going to misinterpret everything I just said, and you are about to get me into big-time trouble!

I had no idea of what the hell Jeffrey was doing in all the years I knew him until it became clear, and then I divorced myself from having anything to do with him. But before that happened, for years and years and years, I watched Jeffrey do all kinds of interesting and amazing things, scientifically and so on.

Yeah. And you said that from the very beginning. And I understand that, and I appreciate you giving me your perspective. The fact that you heard that story firsthand from Maria—

No, you don’t. I am suddenly—I am mad at myself for even talking to you. What’s the name of your publication?

I’m writing for Mother Jones right now.

Yeah, that’s been around for a very long time, since the ’70s, am I right? Or ’60s even?

Yeah, ’70s.

Isn’t that an outgrowth of Woodstock?

No. It’s very politically focused right now and environmentally as well.

What have I done? I have just shot myself in the foot.

Is there anything else that you think—

I am mad at myself! What have I—oh, dammit.

Is there anything—

I don’t trust you. You’re a journalist, and you’re not gonna take time to figure out what I really said.

I have now put myself into terrible trouble when I actually have no idea what the hell Jeffrey was ever doing. Except his scientific things and his supposed art things, I used to help him furnish his house with art. That’s all. And while that was going on—oh boy. What have I done?

I understand, and you spending time with Jeffrey was—

How much do you want to forget this whole conversation?

I’m not gonna take any money.

[Laughing] I know, I’m sorry I said that.

Did you ever spend any time with Jeffrey that wasn’t in a science dinner or in the art world—did you ever have any one-on-one time?

Only those kind of things, and the reason all the kind of people had to do with him—look at the list, it’s incredible. Why? Because Jeffrey was a fascinating guy. He promised money to scientists. I don’t need money because I have money, and I was just a pal of his, but I saw that happen. Scientists spend 50 percent of the time trying to raise money. And Jeffrey was an easy way out.

If you want to know what satyriasis is, get a copy of Psychopathia Sexualis, by Krafft-Ebing. You know that work?

I don’t know that work. But I know the condition you’re talking about.

You ever heard of Krafft-Ebing and Psychopathia Sexualis?

No, but I’m familiar with the term you’re using to say that Jeffrey was afflicted with. You described it as the male counterpart to nymphomania, correct?

Yeah, but if you were a person with any kind of literary knowledge or background, you would have heard of Robert [sic] Krafft-Ebing, the great contemporary of Sigmund Freud, who made an encyclopedia of sexual aberrations.

And that’s your thesis that he was—

Before you write, why don’t you equip yourself with what you’re supposed to know, but don’t, of the background of sexual perversion. Which was studied thoroughly at the time of Freud by Robert Krafft-Ebing, which most educated people know about. You don’t. A shame.

Is there anything—

Excuse me, but that’s the truth of it. You should know that if you had any kind of background. He had a copy, Jeffrey had a copy of that book.

I can tell that you are—

Why don’t you get a copy of it? Read the thing. Very thick. It talks about all imaginable, mad things. All the sexual perversions known to mankind. Before you write, why don’t you look at that, and in one page you’re going to find a thing called satyriasis—these are people who, like Jeffrey, are afflicted. I read some place the other day that he had to have an orgasm three times a day. Did you read that?

I’ve heard that. Yes.

Do you mean you’ve read it?

Yeah. Well, yes.

You’re not equipped to write what you’re writing. You’re not.

I really urge you—before you write, don’t make a fool of yourself and read what’s already written.

I appreciate it.

Because the point is that Jeffrey was afflicted with a disease. And if it was tuberculosis, you wouldn’t call it a perversion because someone coughs too much. Instead, he was uncontrollable, and he had the dough to yield to it and then, by chance, had a partner in it, Ghislaine, who was a basket case. The story is more bizarre than people begin to realize. All you read in the press is the superficiality of the scandalousness of it without realizing that underneath it is the science of the pathology and the medicine of it. I’ve got a great idea for you. Why don’t you look in the Yellow Pages, if there is still such a thing. You know what I mean by Yellow Pages?

Yes, of course.

For some type of sex pathologist or doctors or something, and ask them what their opinion is of people who uncontrollably did what he did, and get a medical background of the thing, and you might begin to write something intelligent on the subject.

I think that’s a good idea. Do you think Maxwell was—

And in exchange for telling you this, why don’t you leave me out of it?

I’m not trying to drag you into anything.

Why did I talk to you! I’m a dead fish, and you’re going to ruin me. Luckily, I don’t know anybody who reads the Mother Jones anymore. I can’t believe it still existed. How many years has this thing been published. Forty?

Just about 50. So you said Maxwell was his partner. Do you think she was pathological as well?

She arrived a dysfunctional wreck from what happened to her on account of her father. And the last thing that should’ve happened to someone like that is to fall in to the care of the likes of Jeffrey. He molded her into being complicit with his aberrations.

What was Maxwell’s role in the operations?

You know as much as I do about that.

So you were never privy to anything?

Jeffrey was a very good friend of mine. And never let on to me as to what was going on, until I finally found out when I saw the Maria Farmer thing, and then I realized that I wanted nothing to do with him.

Did you ever talk to him about that? Did you ever confront him and say, “Hey, I heard this thing”—or did you just cut ties with him? Did you ever confront him?

I can’t remember that, but in any case I stopped having to do with him when I realized the catastrophe that he had done. I couldn’t believe he did that kind of stuff.

So you never talked to him about it?

While, incidentally, everybody he has—what am I saying? What about all these guys like Dershowitz?

Yeah. There were many people who stayed friends with him after that first allegation.

I knew Alan Dershowitz, and Jaron Lanier was a good friend of mine. No, Jaron had nothing to do with it. I’m sure of that.

I knew these guys. Jeffrey introduced me to the scientists. And Steve Gould, who of course had nothing whatever to do with it. Do you know who Steve Gould is?

Yes.

What?

Yeah, I’ve heard the name in regards to Epstein.

You’ve heard the name—he’s one of the greatest scientists of the age, and you heard his name, oh bravo, you’re very qualified. You’re so full of shit, it’s terrible. You should not be writing about this. You’re not qualified.

Oh boy. Why did I pick up the phone? Why wasn’t I out to dinner?

Do you think Dershowitz—

What have I done? You’re going to distort everything I said. I just know it.

You’re being very clear in what you’re saying, and it’s very easy to understand your point of view here.

I never knew what the hell he was doing. On the other hand, however, I was instrumental—I hung out with the scientists. He introduced me to a lot of scientists I otherwise would not have known.

I’m curious what you said about Dershowitz.

How could I possibly know what Alan Dershowitz—I don’t know what Alan Dershowitz did.

Okay, so your point is, you have no clue—

In fact, I can’t believe that anyone as smart as Alan Dershowitz would get involved in anything like that at all. I don’t believe that Alan Dershowitz or any of these other important people were dumb enough to go along with Jeffrey’s—and I believe that that was all the kind of calumnies and lies which this girl—what’s her name? That trollop, who, for months, or whatever the hell she did. What the hell was she doing all this time? And she has made an industry for herself out of inventing calumnies against all of these respectable people.

[Editor’s note: He’s apparently referring to Virginia Giuffre. Giuffre has accused Epstein and Maxwell of sexually abusing her and lending her out for sex to the financier’s powerful friends, among them the lawyer Alan Dershowitz. Dershowitz has adamantly denied the allegations, accusing Giuffre of trying to extort him. Giuffre in turn has sued Dershowitz for defamation.]

So—

None of which can she substantiate. And none of which I believe, because those people she’s talking about—do you think the guy with the intelligence of Alan Dershowitz would dare to compromise himself?

Well, you know, you said Epstein was a smart guy, too, you know?

All right. Who knows. Human nature.

Now, do you think there were parties at the Isle of babes, as you called it?

I’ve heard it called that. I was never invited there.

He insulated me. I was a very close friend, and he insulated me totally. And never let me know that until, to my horror, I realized, and then I had nothing whatever to do with him after that.

Right. So do you know anybody who did go to the island?

No.

No, nobody?

All I know—let’s put it this way. All I know is what I read in the papers.

I had no idea what the hell was going on. Jeffrey had, let us say, two separate worlds going. Do you think his financial friends knew? Of course they didn’t. Could you imagine having all kinds of financial dealings with people if they had any idea what he was doing? They wouldn’t have touched him with a hot potato. He insulated totally those two lives of his.

I see. So what I’m curious about is, we talked about how some people remained friends with him after that first allegation, and you didn’t. Were there any friends of yours who also cut ties with Jeffrey around that time? Or who stayed friends? Did you have any conflicts with people who decided to keep in touch with Jeffrey or go to his dinners, etc.?

No. Boy am I glad that nobody I know reads Mother Jones. I mean, I stopped reading that about 40 years ago.

I see.

Why did I pick up the phone? Listen, I’m going to be mad at you if you misquote me one iota.

I promise you I won’t. I have no interest.

Let’s put it this way: If you misquote me, I’ll raise hell with you. I am not a poor guy.

Okay.

And if you contort anything I told you in good faith—

I have no interest in doing so.

Do you know what I’m saying?

Yeah, you’ve been very clear in the things that you said.

You inveigled me, so to speak, into yapping pointlessly because I have nothing else to do for the moment, and I’m relying on you to understand what I say. If you misquote me or anything like that, I will sue your magazine until the end of the Earth.

I understand. You’ve been very clear in what you’ve said. I will absolutely not distort or misquote you.

Tell me your name again so I can start writing a complaint to sue you.

My name is Leland. But we can go ahead and end the conversation here. I appreciate you offering me your point of view.

Look, it’s been fun, but for heaven’s sakes, please don’t screw me over.

You have my word and you got—

I’ve done you a big favor by telling you a lot of stuff, and I don’t expect you to stab me in the back.

I absolutely have no intention of doing so. You also have—

Otherwise I will stab you in other places.

Okay, you also have my number. So if you feel the need—

Oh, I’ve got your number.

You’ve got it. I appreciate you giving me your perspective on this.

No, you don’t, you’re a journalist. Journalists don’t appreciate nothing. They’re like lawyers.

I’m insulted, but that’s okay. All right. Well, you have a great night.

Ok, have a nice evening. You’ve ruined mine.

You can reach Leland Nally at

[email protected].