CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Lost in Transition

Even before the Supreme Court decision awarded the presidency to the Republicans, the Bush team began behaving as if it had won. The election took place exactly ten years after the buildup of American troops in Saudi Arabia for the Gulf War, and to mark both that occasion and the impending Bush restoration, former president Bush and James Baker had proposed a hunting trip in Spain and England. The original guest list included the usual suspects from the Gulf War -- the senior Bush; James Baker; Dick Cheney; General Norman Schwarzkopf, the commander of U.S. forces during the war; former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft; and, of course, Prince Bandar, whose enormous estate in Wychwood, England, had been an ancient royal hunting ground used by Norman and Plantagenet kings. [1]

The relationship between Baker and the elder Bush had been frayed as a result of the failed reelection campaign of 1992, but the two long-time friends had patched things up as the presidency of George W. Bush became increasingly probable. When he arrived in Austin, Texas, on Election Day, Baker went to Dick and Lynne Cheney's hotel suite to listen to the results. [2] However, by the next morning, Wednesday, November 8, Al Gore was contesting the Florida vote, so Baker was enlisted to lead the legal battle to win the presidency for Bush. As a result, both he and Cheney skipped the European hunting trip.

But the lavish gathering went on as planned. On Thursday, November 9, a private chartered plane from Evansville, Indiana, picked up former president Bush in Washington en route to Madrid, where the hunting trip was to begin. Already on board was a contingent from Indiana. One member was Bobby Knight, the highly successful but extraordinarily temperamental basketball coach who had just been fired from Indiana University. [3] Other hunters on the trip were powerful coal industry executives from the Midwest -- Irl Engelhardt, the chairman and CEO of St. Louis's Peabody Energy, the world's largest coal company; and Steven Chancellor, Daniel Hermann, and Eugene Aimone, three top executives of Black Beauty Coal, a Peabody subsidiary headquartered in Evansville, Indiana.

During the campaign, Bush had proposed caps on the carbon dioxide emissions that scientists believe cause global warming, a regulatory measure that coal executives had not welcomed. But among them, the coal executives had contributed more than $700,000 to Bush and the Republicans. [4] They still had high hopes of participating in energy policy in a Bush administration and loosening the regulatory reins around the industry. Even though the recount battle was just getting under way in Florida, the Bush family was back in action, mixing private pleasure and public policy.

Once in Spain, Bush, Knight, and the executives were joined by Norman Schwarzkopf and proceeded to a private estate in Pinos Altos, about sixty kilometers from Madrid, to shoot red-legged partridges, the fastest game birds in the world. Bush impressed the hunting party as a fine wing shot and a gentleman -- the seventy-six-year-old former president was not above offering to clean mud off the boots of his fellow hunters. Throughout the trip, Bush kept in touch with the election developments via email. By Saturday, November 11, a machine recount had shrunk his son's lead in Florida to a minuscule 327 votes. "I kind of wish I was in the U.S. so I could help prevent the Democrats from working their mischief," he told another hunter in his party. [5]

On Tuesday, November 14, Bush and Schwarzkopf arrived in England, where Brent Scowcroft joined them and they continued their game hunting on Bandar's estate. [6] They kept a close eye on the zigs and zags of the recount battle. As a power play to demonstrate his confidence to the media, the Democratic Party, and the American populace, George W. Bush announced the members of his White House transition team even before the Florida vote-count battle was over.

Bandar eagerly anticipated seeing the Bush family back in Washington. Dick Cheney, Colin Powell, and Donald Rumsfeld were men Bandar already knew quite well. Others who would have access to a new President Bush his father, James Baker, Brent Scowcroft were also old friends.

Moreover, a Bush restoration would also strengthen Bandar's position in Saudi Arabia. During the twelve years of the Reagan-Bush era, Bandar had enjoyed unique powers -- partly because of his close relationship to Bush, partly because he always had King Fahd's ear. But during the Clinton era, Bandar had lost clout. Never an insider in the Clinton White House, he had disliked what he called the "weak-dicked" foreign policy team of the Clinton administration. [7] Bandar had also lost ground in Riyadh because Crown Prince Abdullah, who had effectively replaced the ailing King Fahd, had never been particularly fond of Bandar. But now, on his estate in England, Bandar was once again wired into the real powers that be, and assuming that Bush won, he would be back in a position that no other prominent foreign official could come close to.

***

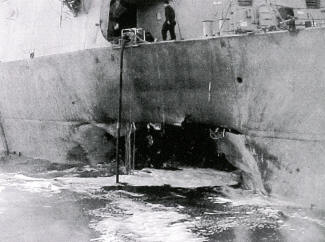

The anticipatory mood of the Bush-Bandar hunting trip contrasted sharply with what was going on in the White House, where, during the last days of the Clinton administration, the central figures in the battle against terrorism were frustrated beyond all measure. In the wake of the bombing of the USS Cole just a few weeks earlier, counterterrorism czar Richard Clarke -- officially, head of the Counterterrorism Security Group of the National Security Council -- felt acutely that the threat of Islamist terror was greater than ever. But since the Clinton administration was leaving office, it was unclear what he would be able to do about it.

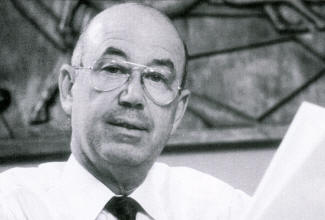

A civil servant who had ascended to the highest levels of policy making, Clarke was a true Washington rarity. As characterized in The Age of Sacred Terror, he broke all the rules. He refused to attend regular National Security Council staff meetings, sent insulting emails to his colleagues, and regularly worked outside normal bureaucratic channels. Beholden to neither Republicans nor Democrats, the crew-cut, white-haired Clarke was one of two senior directors from the administration of the elder George Bush who were kept on by Bill Clinton, and abrasive as he was, he had continued to rise because of his genius for knowing when and how to push the levers of power.

Obsessed with the fear that bin Laden's next strike would take place on American soil, after the USS Cole bombing Clarke had prepared a proposal for a massive attack on Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. But Clarke's plan faced one major obstacle. On Tuesday, December 12, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled by a vote of 5 to 4 that the recount of the disputed votes in Florida could not continue. In effect, it had awarded the presidency of the United States to George W. Bush.

Eight days later, on December 20, 2000, Clarke presented his plan to his boss, National Security Adviser Sandy Berger, and other principals on the National Security Council. But with only a month left in the Clinton administration, Berger felt it would be ill-advised to initiate military action just as the reins of power were being handed over to Bush. [8]

At the same time, Berger was obligated to make clear to the Bush team that bin Laden and Al Qaeda posed a national security threat that required urgent and aggressive action. As a result, in the early days of January 2001, Berger scheduled no fewer than ten briefings by his staff for his successor, Condoleezza Rice, and her deputy, Stephen J. Hadley. [9] Berger decided that it was not necessary for him to go to most of the briefings, but he made a point of attending one he felt was absolutely crucial. "I'm coming to this briefing to underscore how important I think this subject is," he told Rice. [10] At that meeting Clarke presented the incoming Bush team with an aggressive plan to attack Al Qaeda.

The meeting began at 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday, January 3, 2001, in Room 302 of the Old Executive Office Building, a room full of maps and charts that had become home base for Clarke and his chief of staff, Roger Cressey. [11] With Rice present, Clarke launched into a PowerPoint presentation on his offensive against Al Qaeda. Bush administration officials have denied being given a formal plan to take action against Al Qaeda. But the heading on slide 14 belies that denial. It read, "Response to al Qaeda: Roll back." Specifically, that meant attacking Al Qaeda's cells, freezing its assets, stopping the flow of money from Wahhabi charities, and breaking up Al Qaeda's financial network. It meant giving financial aid to countries fighting Al Qaeda such as Uzbekistan, Yemen, and the Philippines. It called for air strikes in Afghanistan and Special Forces operations. The Taliban had been in power in Afghanistan since 1996, and because they were providing a haven for and being supported by Osama bin Laden, Clarke proposed massive aid to the Northern Alliance, the last resistance forces against them.

Most significantly of all, Clarke called for covert operations "to eliminate the sanctuary" in Afghanistan where the Taliban was protecting bin Laden and his terrorist training camps. [12] The idea was to force terrorist recruits to fight and die for the Taliban in Afghanistan, rather than to allow them to initiate terrorist acts all over the world. The plan was budgeted at several hundred million dollars, and Time reported, according to one senior Bush official, it amounted to "everything we've done since 9/11." [13]

After the session, Berger underscored the challenge the next administration faced. "I believe that the Bush administration will spend more time on terrorism generally, and on Al Qaeda specifically, than any other subject," he told Rice.

It seems fair to say that until this point Condoleezza Rice had not taken Islamist terrorism seriously as a threat. Less than a year earlier, in a lengthy article in Foreign Affairs, Rice had voiced her contempt for the Clinton administration's foreign policies, and expressed her views on America's strategic foreign policy concerns. [14] Her brief references to terrorism in the article suggest she saw it as a threat only in terms of the state-sponsored terrorism of Iran, Iraq, Libya, and other countries that predated the transnational jihad of bin Laden and Al Qaeda. And in her speech before the Republican National Convention, Rice had not mentioned terrorism at all. Rather she had suggested that America's most difficult foreign policy challenges would come from China. [15]

After the briefing, Rice, who was about to become Clarke's boss, admitted to him that the dangers from Al Qaeda appeared to be greater than she had realized. Then she asked him, "What are you going to do about it?" According to Clarke, "She wanted an organized strategy review. " [16] But she did not give Clarke a specific tasking.

During the changeover from an old administration to a new one, incoming officials frequently fall victim to "death by briefing" by each component of the government. Thus well-intentioned, carefully prepared plans from one administration may be sacrificed in turf wars or be lost in transition as a new administration takes office. Some members of the Bush team saw setting up a new missile defense system as their highest priority. For his part, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld wanted to overhaul the entire structure of the military. As a result, Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld all wanted to go after Iraq. Clarke's proposal sat there and sat there and sat there.

Nothing happened.

***

Meanwhile, the intricate private networks the Bushes had painstakingly assembled over four decades came alive again in the public sector with astonishing speed. Never before had the highest levels of an administration so nakedly represented the oil industry. Between them, the president, vice president, national security adviser, and secretary of commerce had held key positions in small independent oil companies (Arbusto, Bush Exploration, and Harken Energy), major publicly traded companies (Halliburton and Chevron), and one huge independent Texas oil company (Tom Brown). Secretary of the Army Thomas White was a former high-ranking Enron executive, and Robert Zoellick, the U.S. trade representative, was a member of Enron's advisory board. Others, including Karl Rove and Lewis "Scooter" Libby, Dick Cheney's chief of staff, owned large blocks of Enron stock when they joined the new Bush administration. [17]

But it was not just the oil industry that had access to the White House. Campaign contributors such as coal executives Irl Engelhardt and Steve Chancellor, both among the men who had gone hunting with George H. W. Bush in Spain, were named to Bush's Energy Transition Team. [i] Rewarding campaign contributors with direct access to White House policy makers was suddenly the rule, not the exception. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Engelhardt and Chancellor were among 474 people named by the Bush campaign to serve as key policy advisers during the presidential transition who contributed a total of more than $5.6 million to federal candidates and party committees during the 2000 elections. Ninety-five percent of those campaign contributions went to Bush, other GOP candidates, or the Republican Party. [ii]

All in all, if one looked at George W. Bush's new administration and the people he had brought in from his father's, the extraordinary confluence of power in the public and private sectors created an enormous potential for conflicts of interest and colored serious policy questions -- especially with regard to energy policy and the Middle East. Tens of billions of dollars were at stake. The Bush administration could help decide which companies would be awarded lucrative defense contracts, how to resolve regulatory questions regarding the energy industry, whether sanctions should prohibit trade with oil-producing terrorist states such as Iran, Iraq, and Libya, and a host of other multibillion-dollar issues. Did the long history of incestuous relationships give friends, relatives, and political allies of the Bushes an inside track on winning defense contracts? Would they affect regulation of the energy industry, the Bush administration's position on trade sanctions against Iran and Iraq, or oversight of industry giants such as Enron? Given the Bush family's relationship with the House of Saud, not to mention its new alliance with Islamist groups in America, how closely would the new administration examine the rise of Islamist terrorism?

As the day approached when George W. Bush would be sworn into power, the Saudis and the Bushes decided that the occasion called for a joint celebration. On Friday, January 19, the night before the inauguration, the Baker Botts law firm threw a party for the elder George Bush and Prince Bandar at the Ronald Reagan Building, the mammoth international trade center just a few blocks from the White House. Not long afterward, unprompted, one of Bandar's aides at the Saudi embassy told a visitor, "Happy days are here again." [18]

Now that the Bush team had retaken the White House, its friends in the private sector had more clout than ever. Just after the inauguration, in early February, Rumsfeld met with fellow Princeton wrestling teammate Frank Carlucci, also a former secretary of defense, who had led the way for the Carlyle Group's massive defense acquisitions. Carlucci said the meeting did not constitute a conflict because he was not lobbying his old friend. [19] "I've made it clear that I don't lobby the defense industry," Carlucci stated. But at the time, Carlyle still had several projects under consideration by the Pentagon that were potentially worth billions in contracts, and Carlucci, James Baker, Richard Darman, and other Bush allies might profit from them. [iii] Most notable among these projects was United Defense's $11-billion contract for the Crusader tank, a gigantic Cold War-inspired weapon that was widely seen as obsolete, but which managed to stay in the budget. [20] [iv]

Bush's allies were also well positioned to take advantage of the new administration's close ties to the Saudis. On February 5, just two weeks after the inauguration, Baker Botts announced that it had established a new office in Riyadh, presumably to better service its Saudi clients. "The kingdom has opened its doors to Western clients," explained managing partner Richard Johnson, "so we need to have a presence in the region." [21] Later that year, the firm acquired another powerful friend in the region when Bush named the new ambassador to Saudi Arabia -- Robert Jordan, the Baker Botts attorney who had represented Bush during the SEC's investigation into the Harken Energy insider trading allegations against him. In addition to representing such oil giants as ExxonMobil, ARCO, BP Amoco, and Halliburton, all of which did business with the Saudis, Baker Botts enjoyed the confidence of corporate clients whose businesses could be affected by the administration's policies. Highest on this list were the Carlyle Group and Dick Cheney's company, Halliburton, both of which had hundreds of millions of dollars in business with the Saudis.

Reporters have widely noted that Halliburton also stood to benefit from the friendly new administration. Almost immediately after the inauguration, Halliburton opened an office in Tehran, a move that, according to the Wall Street Journal, was "in possible violation of U.S. sanctions." Halliburton publicly called for lifting the sanctions against working in Iran, but insisted it was not violating U.S. laws because the company in question was a Halliburton subsidiary, not the domestic company itself. [22]

Rather than crack down on Halliburton, however, the Bush administration's Energy Task Force, which was headed by Cheney, presented a draft report in April 2001 saying the United States should reevaluate the sanctions against Iran, Iraq, and Libya that prohibited U.S. oil companies from "some of the most important existing and 'prospective' petroleum-producing countries in the world." Cheney asserted there was no conflict on his part because "Since I left Halliburton to become George Bush's vice president, I've severed all my ties with the company, gotten rid of all my financial interest." [23] Cheney neglected to mention that he was still due approximately $500,000 in deferred compensation from Halliburton and could potentially profit from his 433,333 shares of unexercised Halliburton stock options. [24] [v]

But more to the point, Cheney, as secretary of defense during the Gulf War, had begun a warm relationship with the Saudis. Even though he had little experience in the private sector, after he left his cabinet post, Halliburton had selected Cheney as CEO because of such contacts, so that the oil giant might expand its largely domestic portfolio into foreign markets, including Saudi Arabia. [vi] In his last year at Halliburton, Cheney had received $34 million from the company. Now Cheney was back on the other side of the revolving door, in a position to do business with his benefactors, and he had been uniquely sensitized to Saudi needs.

Meanwhile, the biggest foreign-policy initiative in the early days of the administration was a secretive one -- how to get rid of Saddam Hussein. "It was all about finding a way to do it," said former secretary of the treasury Paul O'Neill, who as a cabinet secretary, was a member of the National Security Council. "That was the tone of it. The president saying, 'Go find me a way to do this.' For me the notion of preemption, that the U.S. has a unilateral right to do whatever we decide to do, is really a huge leap." O'Neill added that such questions as "Why Saddam?" and "Why now?" were never discussed. [25]

According to O'Neill, as reported in The Price of Loyalty by Ron Suskind, plans for occupying Iraq were discussed just days after the inauguration in January 2001. By March, the Pentagon had drawn up a document entitled "Foreign Suitors for Iraqi Oilfield Contracts."

Ironically, three key figures in the administration -- Dick Cheney, who had been a prominent Republican congressman, Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had been national security adviser, and Donald Rumsfeld, who had been Reagan's special presidential envoy to Iraq -- had all played vital roles in giving Saddam Hussein a pass back in the Reagan-Bush era. Cheney and Rumsfeld had since become quite hawkish on Iraq -- both were part of the Project for a New American Century -- but Colin Powell remained convinced that Saddam was not a real threat. "Frankly, the sanctions [against Iraq] have worked," he said in February 2001. "Saddam has not deployed any significant capability with respect to weapons of mass destruction. He is unable to project conventional power against his neighbors." [26] [vii]

***

As the first year of the Bush administration got under way, throughout the intelligence world analysts again and again heard in the "chatter" of monitored conversations that a major new Al Qaeda operation was in the works. At times, the intelligence was so cluttered with rumors, misinformation, and disinformation that, understandably, it was almost impossible to ferret out the vital clues. At other times, veteran FBI and CIA agents repeatedly discovered suspicious activity that they reported to their superiors. Not all, but substantial numbers of these reports found their way to the most senior counterterrorism official in the country, Richard Clarke.

In 2001, Clarke and Roger Cressey stayed on at the NSC with the new administration. They followed up their briefings with Condoleezza Rice with a memo on January 25, 2001, saying that more Islamist terrorist attacks had been set in motion since the bombing of the USS Cole. Worse, they reported that U.S. intelligence now believed that there were already Al Qaeda "sleeper cells" in America. [27]

Clarke and Cressey were not alone in their awareness of the growing threat. Six days later, on January 31, a bipartisan commission led by former senators Gary Hart and Warren Rudman warned Congress that a devastating terrorist attack on U.S. soil could be imminent. In the report, seven Democrats and seven Republicans unanimously approved fifty recommendations in hopes of addressing the commission's assessment that "the combination of unconventional weapons proliferation with the persistence of international terrorism will end the relative invulnerability of the U.S. homeland to catastrophic attack." [28]

Not long after the commission's report was released, on February 7, CIA director George Tenet testified in Congress that "Osama bin Laden and his global network of lieutenants and associates remain the most immediate and serious threat" to American security. [29]

Nevertheless, even with CIA support, the recommendations of the Hart-Rudman Commission didn't get far. As Hart later lamented, "Frankly, the White House shut it down. The president said, 'Please wait, we're going to turn this over to the vice president. We believe FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] is competent to coordinate this effort.' And so Congress moved on to other things, like tax cuts."

By early February, intelligence analysts had definitively nailed down Al Qaeda's involvement in bombing the USS Cole. As a candidate, in the wake of the attack, Bush had said, "I hope that we can gather enough intelligence to figure out who did the act and take the necessary action. There must be a consequence." [30] Richard Clarke had a specific response in mind. He now argued for striking Al Qaeda's training camps at Tarnak Qila and Garmabat Ghar in Afghanistan -- easy targets that were important because thousands of terrorist recruits trained there to fight the Northern Alliance, the Afghan rebel coalition, or against American interests.

But the Bush administration did not go along with it. Condoleezza Rice and her deputy, Stephen J. Hadley, reportedly admired Clarke's fervor. But they believed Clarke's strategy of battling Al Qaeda would not work. "The premise was, you either had to get the Taliban to give up Al Qaeda, or you were going to have to go after both the Taliban and Al Qaeda together," Hadley told the Washington Post. "As long as Al Qaeda is in Afghanistan under the protection of the Taliban ... you're going to have to treat it as a system and either break them apart, or go after them together." [31]

In the Clinton administration, Clarke's colleagues had been on watch during the attacks against Americans in Riyadh, Kenya, Tanzania, and on the USS Cole, and terrorism came up at cabinet meetings nearly every week. But according to army lieutenant general Donald Kerrick, who managed the National Security Council staff and stayed at the NSC through the spring of the new administration's first year, Bush's advisers were not focused on it. "That's not being derogatory," Kerrick said. "It's just a fact. I didn't detect any activity but what Dick Clarke and the CSG were doing." [32] Without a clear-cut consensus behind them at the highest levels of the Bush administration, Clarke's proposals had to be subjected to a policy review that would take months. In the meantime, there was nothing to take their place. As a result, the tough rhetoric against terrorism espoused by Bush during the campaign was not backed up by action.

One development that typified the bureaucratic inertia was the Bush administration's failure to use the Predator aerial vehicle -- an unmanned drone that, without risk to human life, was able to deliver thousands of photos of Al Qaeda's terrorist training camps. It had been deployed quite successfully during the Clinton administration, but now it was not even being used because of arguments between the Pentagon and the CIA over who should pay for it. [33]

Meanwhile, bin Laden's operatives were on the move. Some had already entered the United States. Over the next few months, others completed their training in Afghanistan and prepared to enter the United States. One already in the United States was a Saudi named Hani Hanjour, from the resort town of Taif. In January and February, Peggy Chevrette, a manager at the Jet Tech flight school in Phoenix, notified the Federal Aviation Administration three times that Hanjour lacked the necessary flying skills for the commercial pilot's license he had obtained in 1999. In response, an FAA inspector checked Hanjour's license and even sat next to him in a class. But the FAA said the inspector observed nothing that warranted further action. [34]

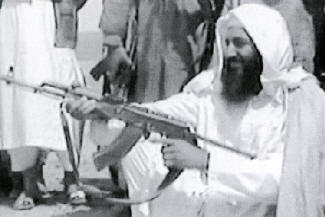

On February 26, 2001, Osama bin Laden attended the wedding of his son Mohammed, in the southern Afghan town of Kandahar, and read aloud a poem that appeared to refer to the bombing of the USS Cole. According to the Saudi paper al-Hayat, the poem read:

Your brothers in the East prepared their mounts and Kabul has prepared itself and the battle camels are ready to go. A destroyer: even the brave fear its might. It inspires horror in the harbor and in the open sea. She goes into the waves flanked by arrogance, haughtiness, and fake might. To her doom she progresses slowly, clothed in a huge illusion. Awaiting her is a dinghy, bobbing in the waves, disappearing and reappearing in view.

The bin Ladens had claimed they were completely estranged from Osama, but that was clearly not the case. The wedding was also attended by bin Laden's mother, two brothers, and a sister. [35] In addition, at roughly the same time, also in February, pro West intelligence operatives saw two of Osama bin Laden's sisters taking cash to an airport in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, where, the New Yorker reported, they were "suspected of handing it to a member of bin Laden's Al Qaeda organization. " [36]

A few days after the wedding in Kandahar, thirteen Al Qaeda operatives recorded farewell videos before ending their training. In one of them, which was broadcast on the Arab TV news station Aljazeera in September 2002, Ahmed Alhaznawi pledged to send a "bloodied message" to Americans by attacking them in their "heartland." [37] In a similar video, Abdulaziz Alomari, another Al Qaeda operative, who was a graduate of an Islamic college in the Saudi province of El Qaseem, made an apparent reference to his last testament: "I am writing this with my full conscience and I am writing this in expectation of the end, which is near. ... God praise everybody who trained and helped me, namely the leader Sheikh Osama bin Laden." [38] Other videos showed operatives studying maps and flight manuals in preparation for their mission.

In March, the Italian government gave the Bush administration information based on wiretaps of two Al Qaeda agents in Milan who talked about "a very, very secret plan" to forge documents for "the brothers who are going to the United States." [39]

On April 18, U.S. airlines got a memo from the FAA warning that they should demonstrate a "high degree of alertness" because Middle Eastern terrorists might try to hijack or blow up an American plane. [40] By this time, airlines had been receiving one or two such warnings per month but the threats were so frequent and, often, so vague, they had little impact on security. Likewise, beginning in May, over a two-month period, the National Security Agency reported "at least thirty-three communications indicating a possible, imminent terrorist attack." But, according to congressional testimony, none of the reports provided specific information on where, when, or how an attack might occur. [41] There were so many warnings that officials grew numb to them.

Yet inexplicably, in the context of so many warnings, the Bush administration introduced policies that could only be counterproductive. Far from cracking down on the Taliban, in May, Colin Powell announced that the United States was actually giving $43 million to the Taliban because of its policies against growing opium. "Enslave your girls and women, harbor anti U.S. terrorists, destroy every vestige of civilization in your homeland, and the Bush administration will embrace you," wrote columnist Robert Scheer in the Los Angeles Times. "All that matters is that you line up as an ally in the drug war, the only international cause that this nation still takes seriously. ... Never mind that Osama bin Laden still operates the leading anti-American terror operation from his base in Afghanistan, from which, among other crimes, he launched two bloody attacks on American embassies in Africa in 1998." [42]

Then, in June, the American embassy in Saudi Arabia initiated new security measures that could only be described as absurd, announcing that its new Visa Express program would allow any Saudi to obtain a visa to the United States -- without actually appearing at the consulate in person. The United States waives visas for twenty-eight countries, mostly in Western Europe. But Saudi Arabia was to be the only nation to enjoy the privileges of this new program, launched, in the most fertile breeding ground for terrorists in the world, for a simple reason: convenience. An official embassy announcement said, "Applicants will no longer have to take time off from work, no longer have to wait in long lines under the hot sun and in crowded waiting rooms." [43]

According to Jessica Vaughan, a former consular officer, Visa Express was "a bad idea" because the issuing officer "has no idea whether the person applying for the visa is actually the person (listed) in the documents and application."

Another official described the program as "an open-door policy for terrorists." [44]

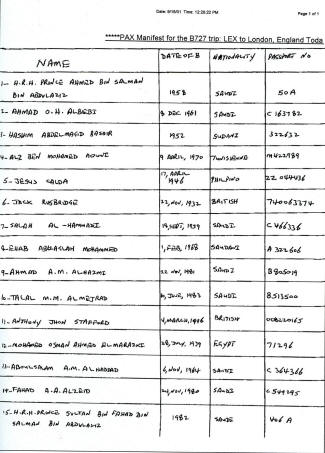

And it was -- quite literally. Before the program was in place, eleven Al Qaeda operatives had already made their way to the United States in preparation for September 11. But thanks to Visa Express, three Saudis -- Abdulaziz Alomari, about twenty- eight years old, Khalid Almidhar, twenty-five, and Salem Alhazmi, twenty, began their journey to September 11 without the inconvenience of even having to wait in line.

***

Meanwhile, Bush had not forgotten that one of the constituencies that helped get him to the White House consisted of Islamic fundamentalists. Having depended so heavily on Muslim-American organizations during the Florida campaign, the Bush administration continued its "outreach" to Muslims. On June 22, 2001, Karl Rove addressed 160 members of the American Muslim Council on Bush's faith-based agenda in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, which is adjacent to the White House and part of the White House complex.

The meeting stirred up controversy even before it took place. The scheduled speaker had actually been Cheney. But that morning, a front-page headline in the Jerusalem Post read, "Cheney to host pro-terrorist Muslim group." Citing logistical conflicts, Cheney canceled and Rove took his place. [45] Conservative pro-Israeli activists felt the Bush administration should be more careful about the Muslim activists that Grover Norquist was bringing into the White House. In this case, they had argued against the meeting because of the AMC's stance supporting Hamas, a sponsor of suicide bombings in Israel. [46] Nevertheless, the meeting went forth as scheduled, and Abdurahman Alamoudi, one of AMC's founders, attended, even though less than a year earlier he had appeared at a White House demonstration where he said, "We are all supporters of Hamas." [47] [viii]

The Secret Service requires White House visitors to submit their Social Security number and birth date for security reasons. But on this occasion, someone of even more dubious background than Alamoudi slipped by them -- Sami Al-Arian, the professor at the University of South Florida who had campaigned for Bush. At the time, Al-Arian had been under investigation by the FBI for at least six years, and several news accounts had reported that federal agents suspected he had links to terrorism.

***

At roughly the same time Bush's staff was wooing Al-Arian, counterterrorism agents were digging up detailed information on terrorists that could be acted upon -- but even then they were thwarted. In July 2001, a highly regarded forty-one-year-old FBI counterterrorism agent in Phoenix named Kenneth Williams was investigating suspected Islamic terrorists when he noticed that several of them were taking lessons to fly airplanes. [48] Williams became more suspicious after he heard that some of the men had been asking questions about airport security procedures. His supervisor, Bill Kurtz, thought Williams might be onto something and proposed monitoring civil aviation schools to see if bin Laden's operatives had infiltrated them. But, according to Newsweek, in Washington, Kurtz's proposal was completely ignored. Because George Bush had criticized the practice of racial profiling of Arab Americans in his presidential campaign, the FBI now pointedly avoided such measures. In addition, after John Ashcroft, the new attorney general, had taken office in January, the Justice Department had been directed to focus on child pornography, drugs, and violent crime -- not counterterrorism.

Other bin Laden operatives were on the move. In early 2000 two of bin Laden's operatives, Khalid Almidhar and Nawaf Alhazmi, arrived in Los Angeles fresh from an Al Qaeda planning summit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. In L.A., they were soon befriended by Omar al-Bayoumi, the Saudi who had received payments from Prince Bandar's wife, Princess Haifa bint Faisal. [49] In addition to throwing a party for them in San Diego to welcome them to the United States, al-Bayoumi guaranteed the lease on their apartment and, Newsweek reported, also paid $1,500 for the first two months' rent. [ix] In July 2001, al-Bayoumi left the United States, but the monthly payments from Princess Haifa of about $3,500 began flowing instead to his associate, Osama Basilan, the Saudi Al Qaeda sympathizer in California who also aided the terrorists. According to Newsweek, it was unclear whether the money given to the hijackers came from al Bayoumi or Basilan. There is no evidence that Princess Haifa or Prince Bandar knew they may have been indirectly subsidizing Al Qaeda. Bandar has denied all allegations that he or his wife knowingly aided terrorists.

***

Another reason Prince Bandar looked forward to the return of the Bushes was that he expected the incoming president to help resolve the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. In the final days of the Clinton era, Bandar had quietly gone back and forth between Washington and Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat in a frantic attempt to resolve the Palestinian issue. Hardly a fan of Clinton's, even Bandar recognized that Clinton's new peace plan, which would have given the Palestinians 97 percent of the occupied territories, much of Jerusalem, and $30 billion in compensation, was the best deal ever offered to Arafat. Conditions in the Middle East were always volatile -- the Palestinians, Israelis, Arabs, and the United States all had their own internal politics to contend with -- it was possible that the opportunity for a settlement could quickly vanish.

But in January 2001, as Inauguration Day approached, the obstinate Arafat turned the deal down. The negotiations had failed. Exhausted, Bandar still hoped that the intractable conflict could finally be resolved. According to the New Yorker, before Bush was sworn in, Colin Powell assured Bandar that the new administration would enforce the same Middle East deal that Clinton had negotiated. [50] Within a few weeks, however, Bandar met with the new president and emerged quite upset: Bush had told him that he did not intend to take an aggressive role in mediating the conflict. [51] Historically, the House of Saud had refrained from intervening as forcefully as it might have on the side of the Palestinians. But Israel had killed 307 Palestinians and injured 11,300 during the previous year, [52] and now a great opportunity for peace was slipping away. In February, the hawkish Ariel Sharon was elected to replace Ehud Barak as prime minister of Israel. The violence in Israel continued to escalate. Now that satellite TV was broadcast throughout the Arab world, the news was relentless in Riyadh. Saudis who turned to Aljazeera saw Israeli soldiers attacking Palestinians hour after hour, day after day. On March 3, Palestinians were killed by Israelis in three separate incidents. [53] In April, a Palestinian cabinet minister accused Israel of using a car bomb in an attempt to assassinate a Fatah activist. That same month, Israelis shot dead a fourteen-year-old Palestinian in the West Bank village of Beit Ummar. [54]

Yet the Bush administration blamed all the violence on Arafat. In private conversations with the Saudis, people in the administration said that the president would not waste his slim political capital on what he saw as an unsolvable mess. [55] Their calculus made sense; Bush had been president for only a few months, needed to press his domestic agenda, and was barely legitimate in the eyes of many Americans.

But as a result, Bush's standing in the House of Saud suddenly plummeted. He appeared to be drawing too close to Ariel Sharon and was doing nothing to help the Middle East peace process. In May, Saudi crown prince Abdullah even turned down an invitation to the White House. "The U.S. enjoys a distinguished position as the leader of the new world," he said. "And like it or not, this requires it to meet crises before they get out of hand." [56] Never before had Abdullah been so blunt in criticizing the United States.