Part 1 of 2

"This guy talks to God"

When they found Dr. Hugo Spadafora in September 1985, they found everything but his head. The rest of him had been tied up in a U.S. mail sack and dumped under a bridge on the border of Costa Rica and Panama.

His body bore evidence of unimaginable tortures. The thigh muscles had been neatly sliced so he could not close his legs, and then something had been jammed up his rectum, tearing it apart. His testicles were swollen horribly, the result of prolonged garroting, his ribs were broken, and then, while he was still alive, his head had been sawed off with a butcher's knife.

The horrors of Hugo Spadafora's death brought thousands of people into the streets of Panama City, where they formed a miles-long human chain of outrage and lament. The dashing young doctor had been a hero to many Panamanians— an unusual mix of revolutionary warrior and middle-class professional.

When he was murdered, Spadafora had been fighting for the Contras in Costa Rica, at the side of his old friend Eden Pastora. They had fought together in the 1970s against the Somoza dictatorship, with Spadafora leading an international brigade of jungle fighters—the Brigada Internacional Simon Bolivar—in support of Pastora's southern forces. After the Sandinistas became too oppressive for Pastora's liking, he joined the CIA and took over command of a Contra army in Costa Rica. Hugo Spadafora gave up his medical practice in Panama and, with his wife Winy, moved to Costa Rica to take up arms with Pastora once again— this time against their old Marxist comrades.

The Reagan administration's Contra PR machine couldn't have dreamed up a better freedom fighter than Hugo Spadafora. The DEA called him "reportedly the best known guerrilla fighter in Central America." He was so popular in Panama that the country's civilian president, Nicolas Barletta, announced an immediate investigation into his shocking murder. It was to be one of Barletta's last official acts. A few weeks later he was forced to resign by Manuel Noriega, the commander of the country's military, and the promised investigation never \ occurred. Charged with masterminding Spadafora's murder, Noriega was convicted in absentia by a Panamanian court in 1993.

The New York Times, in a June 1986 story that first exposed Noriega as a drug dealer and money launderer, cited Spadafora's murder as an example of why U.S. government officials were growing tired of the tyrant. "Officials in the Reagan Administration and past Administrations said in interviews that they had overlooked General Noriega's illegal activities because of his cooperation with American intelligence," the story said. "They said, for example, that General Noriega had been a valuable asset to Washington in countering insurgencies in Central America and was now cooperating with the Central Intelligence Agency in providing sensitive information from Nicaragua."

But the Times story left unaddressed a rather obvious question: why would a cunning political strategist like Noriega take the risky step of having the popular Spadafora, Panama's former vice minister of public health, kidnapped by government security men in full view of dozens of witnesses, and decapitated?

The answer, which may be the reason the Times sidestepped the issue, involved drugs and the CIA. When Noriega's goons hauled Spadafora off a bus at the Panamanian border, he was on his way to Panama City, where he intended to publicly release evidence of Noriega's cocaine-smuggling activities— activities that also involved the Contras in Costa Rica. Before leaving for Panama, Spadafora had excitedly told friends that he now had the proof he needed to document the dictator's participation in cocaine trafficking, and he was convinced that the revelations would sink the tyrant.

In the months before his murder, the doctor had befriended a drug and arms smuggler who once ran Noriega's dmg operation, Floyd Carlton Caceres. Carlton, who also served as Noriega's personal pilot, began confiding in Spadafora, sharing intimate details of Noriega's drug trade. "Dr. Spadafora was a very honest man," Carlton said. "He was an idealist and he tried to get the best for anyone needing justice."

If anyone needed justice right then, it was Floyd Carlton. The smuggler was lying low, trying to avoid a hit man Colombian dealers had sent after him. Carlton had lost $1.8 million in cash the Colombians had entrusted to him to fly from Los Angeles to their banks in Panama City. Since he was too busy to do it himself, he'd delegated the task to an underling, who later turned up in Miami, sans cash.

"I had to pay that money," Carlton said, which he agreed to do by flying a dmg load north for free. But again, he'd sent someone else to fly the mission, one of his partners, Teofilo Watson. Watson had never returned, disappearing with 530 kilos of cocaine. Now the Colombians were really angry.

"They thought I had agreed or made a plan with Mr. Watson to steal the drug," Carlton said. Carlton suspected that Costa Rican Contra leader Sebastian "Guachan" Gonzalez and his strange M-3 Contra group had done Watson in, leading him into an ambush at an airstrip owned by the local CIA man, John Hull. "They killed him and then took the airplane and the drugs to Mr. Hull's ranch," Carlton testified. The plane was cut up and thrown into a river that ran through Hull's property, and the cocaine was spirited to the United States, where it may have been traded for weapons.

The Colombians sent a hired killer named Alberto Aldimar out to find Carlton and the cocaine. Aldimar started by kidnapping Carlton's friends and employees and slapping them around. One of his relatives, Carlton said, "was brutally beaten." Then the power shovels arrived and began digging up Carlton's ranch. "They spent weeks there looking for some type of metal and found nothing," he said. Next the Colombians kidnapped the daughter of the Contras' CIA liaison, John Hull, on whose ranch the theft supposedly had taken place. Hull ransomed the girl back unharmed and blamed it on the Communists.

After that, Carlton bolted Central America altogether and took refuge in Miami, the U.S. headquarters of his cocaine transportation network. That's where Spadafora found him, in hiding. "He was trying to unmask Noriega and he was successful in obtaining truth that could imperil Noriega," Carlton later testified.

That in large part was due to Carlton, who would later astonish DEA officials with his photographic recall of Noriega's drug deals. Carlton eventually became the U.S. government's star witness against the Panamanian dictator at his trial on drug charges. The pilot gave Spadafora the names of other pilots involved and the dates of specific-drug flights through Costa Rica. He also implicated Noriega's high school buddy, "Guachan" Gonzalez, who was then hiding out in Panama from a Costa Rican cocaine indictment.

When he was finished, Carlton said, Spadafora announced, "I am going to have a bomb explode in Panama. I am going to set it off with all this information which I have." Hurrying back to Costa Rica, Spadafora began sharing his discoveries with law enforcement and intelligence officials, which may have been his worst mistake.

News of Spadafora's visit to the DEA's offices in San Jose was quickly relayed back to CIA headquarters in Langley, which was informed that "Hugo Spadafora had made vague allegations to DEA. . .that [Guachan] Gonzalez, Manuel Noriega and [another Contra leader] were engaged in drug trafficking. The chief of the local DEA office [Robert Nieves] met Spadafora twice and. . .Spadafora had promised that he would provide evidence of drug trafficking by Gonzalez."

If Nieves needed a way to confirm the doctor's explosive claims, he had just the man for the job—his deep-cover informant Norwin Meneses. In addition to Meneses's connections within the Contras, the trafficker was a close friend and trafficking partner of the Contra official Spadafora was trying to unmask, "Guachan" Gonzalez.

Somehow Meneses's lieutenants got wind of what Spadafora was planning, and they began devising a counterattack. During their investigation of Meneses aide Horacio Pereira, the Costa Rican police taped Gonzalez and Pereira discussing Spadafora's probe and plotting ways to silence him. The Costa Rican newspaper La Nacion obtained copies of the tapes and printed partial transcripts. One ploy Gonzalez and Pereira batted around was paying a witness in Guanacaste Province between $200,000 and $300,000 falsely accuse Spadafora of drug trafficking and exonerate Gonzalez of his pending Costa Rican drug charges.

"Now he's surrounded because if he comes over here, he's finished," Gonzalez confidently told Pereira in a phone call from Panama.

"Yes," Pereira replied. "If he shows up over there, you'll get him."

The district attorney in the Panamanian province where Spadafora was murdered ordered Gonzalez arrested in 1990 for allegedly offering to pay someone to kill the doctor, but no charges were filed, and Gonzalez was quickly released. He has strenuously denied any involvement in Spadafora's death, but Spadafora's family remains convinced Gonzalez played a major role.

Though Noriega apparently felt the information Spadafora possessed was important enough to kill him over, DEA official Robert Nieves had a very different reaction. He told La Nacion that his discussions with Spadafora were "not important" and said he did nothing with the information the doctor had risked his life to bring him. Since Noriega's drug dealing was the official reason the United States invaded Panama four years later, Nieves's professed inaction is astounding. But it would not be out of character for the DEA at that time.

Floyd Carlton testified that he got the same cold shoulder from the DEA office in Panama City when he tried telling them about Noriega's drug dealing in January 1986. "I did actually make contact with intelligence agents in the United States Embassy in Panama," Carlton related. "And I asked, 'Have you not heard my name?' And they said, 'Yes, we have.' And so I said, 'On different occasions I have sent people to speak to you so that you interview me. But you have always told them that you have nothing to talk to me about. And the fact is that I believe that I can go before the American judicial system and speak of a lot of things that are happening in this country, and I can even prove them.'

"So they asked, 'Such as what?' So, I said, 'Money laundering, drugs, weapons, corruption, assassinations.' When I mentioned the name of General Noriega, they immediately became upset." Carlton said the DEA agents "did not try to contact me again. And the only thing that I asked for was protection for myself and my family. And at that time I had no problems with the American justice system."

Judging from the DEA's response to a Freedom of Information Act request, Nieves took a similarly incurious stance when his informant turned up with his head missing. Apparently, none of the DEA's Costa Rican agents ever looked into the doctor's gruesome death. All the agency had on Spadafora, it claimed, was a couple of paragraphs culled from Panamanian newspaper stories written a year after the murder.

The CIA's reaction was even more bizarre. Its Costa Rican station chief, Joe Fernandez, helped Noriega plant false media reports about who really killed Hugo Spadafora.

Jose Blandon, then Noriega's consul general in New York, told Congress that he and Noriega discussed Spadafora's murder a few weeks after the body was found, during a long flight home from New York aboard the dictator's private Lear Jet. Noriega, who'd been in France when Spadafora was killed, wanted an update on how the public was reacting to the killing, the diplomat said. "Especially, he was interested in the developments regarding a witness whose name is Hoffman, a witness of German origin who appeared on Panamanian television saying that he knew who had killed Spadafora and publicly said that Spadafora had been killed by the FMLN [leftist guerrillas] of El Salvador," Blandon testified.

The German, Manfred Hoffman, "was a witness who was created by Noriega, and he was obtained through the CIA operating in Costa Rica," Blandon testified. "He is a specialist in electronics and he worked for the CIA in some cases." Blandon, describing the episode as "an absurd farce," said he told Noriega "nobody believed that story."

A month after Spadafora's killing, Noriega's men contacted the CIA and asked for help in "defusing an effort by family members of slain rebel Hugo Spadafora to implicate Manuel Antonio Noriega in drug trafficking." The CIA cable discussed putting Gonzalez on a popular morning radio talk show to discredit Spadafora's brother, who was trying to obtain Costa Rican documents implicating the Contra commander as a drug dealer. According to a handwritten note on the CIA cable, brother Winston was barking up the right tree: "If the truth be told," someone had written, "we had reason to believe that Gonzalez has been involved in drugs about a yr, 1 Vi yrs ago."

Actually, it was longer than that. A CIA contract agent had first reported on Gonzalez's drug dealings in October 1983, after Spadafora had informed him that "Noriega was smuggling drugs with the Contras and that Gonzalez was involved." The agent said his CIA supervisor simply "replied that CIA had heard some rumors of drug trafficking involving the Contras."

Unfortunately for Spadafora's wife and family, the good doctor had the bad luck of being murdered at a politically inconvenient time. It was in no one's interests right then—Noriega's or the U.S. government's—to delve too deeply into the crime for fear of what would be exposed: the apparent complicity of two CIA assets—Noriega and Gonzalez—in the murder of someone trying to expose government drug trafficking.

At that point the Reagan administration was nuzzling up to Noriega as it had never done before, frantically searching for ways around the 1984 congressional ban on CIA support to the Contras. For months, a steady stream of high-ranking visitors from Washington had been paying courtesy calls to the despot, reminding him of how much Uncle Sam liked and needed him.

In June 1985, aboard a luxurious yacht anchored in the Pacific port of Balboa, North and Noriega struck a very important bargain, said Jose Blandon, who attended the meeting. "Colonel North was interested in gaining Panama's support for the Contras and he particularly requested training assistance in bases located in Panama," Blandon told Congress in 1988. "General Noriega promised to provide training in specific locations to members of the Contras, training to be provided at bases located in Panama." He was also willing to allow Contra leaders free access to the country, and made it clear to North that he was willing to do much, much more.

According to government documents filed during North's trial, Noriega offered to have the entire Sandinista leadership assassinated in exchange for "a promise from the U.S. government to help clean up Noriega's image." North raised the proposal at a top level meeting in Washington and made it clear that "Noriega had the capabilities that he had proffered." North was instructed to tell Noriega that the administration wasn't keen on murdering Nicaraguan government officials, but that Panamanian assistance with sabotage would be another story.

A month after Spadafora's body was found under the bridge, North went back to Panama for another visit, this time to assure the dictator that the U.S. government would be boosting Noriega's foreign aid payments. Within a year an additional $200 million in U.S. taxpayer funds and bank loans was sent his way.

Meanwhile, a former staffer on the National Security Council, Dr. Norman A. Bailey, was frantically trying to alert various high-ranking government officials to the fact that Noriega was in bed with drug traffickers and other criminals.

Bailey, the NSC's former director of planning, had discovered that Panamanian banks were taking in billions of dollars in $50 and $100 bills, money that Bailey concluded could only have come from criminal activities.

Bailey set off on a quixotic quest to persuade the Reagan administration to distance itself from Noriega, pressing his reports into the hands of Reagan's top advisers, including national security adviser Admiral John Poindexter. "I took the initiative myself after the murder of Dr. Spadafora," Bailey testified. "As far as I know, the only thing that actually took place was that Admiral Poindexter added Panama to a trip he was making to Central America in December of 1985."

But Poindexter's meeting with Noriega was hardly what Norman Bailey had envisioned. According to Jose Blandon, who was in attendance, Poindexter did bring up the Spadafora murder, but only to give Noriega some friendly advice on how to handle it; Poindexter "spoke of the need to have a group of officers be sent abroad, outside of Panama, while the situation changed and the attitudes changed regarding Spadafora's assassination."

Noriega met CIA director William Casey after that, again to discuss his help for the Contras. According to a Senate subcommittee report, Casey decided not to raise the allegations of Noriega's cocaine trafficking with him "on the ground that Noriega was providing valuable support for our policies in Central America."

While all of this official ring-kissing was going on, Oliver North and the CIA were quietly knitting parts of Noriega's drug transportation system into the Contras' lines of supply—and hiring drug smugglers to make Contra supply flights for them.

At the time of his visits with Noriega, North was firmly in control of the Contra project, having been handed the ball personally by CIA director Casey. Far from being the dopey, gap-toothed zealot portrayed by the Reagan administration and the press, North was one of the most powerful men in Washington. "The spring of 1985, he was the top gun," testified Alan Fiers, the CIA's Central American Task Force chief and North's liaison at Langley. "He was the top player in the NSC as well. And there was no doubt that he was—he was driving the process, driving the policy."

Former Iran-Contra special prosecutor Lawrence Walsh, who indicted and convicted North on a variety of felonies, suspects the Marine officer was a cutout for the CIA, a human lightning rod to keep the agency from becoming directly involved in illegal activities. "The CIA had continued as the agency overseeing U.S. undercover activities in support of the Contras after the Boland amendments were enacted," Walsh wrote in his memoirs. "The CIA's strategy determined what North would do."

In a city where information is power, North had access to the nation's deepest secrets, subjects so highly classified even top CIA officials didn't know about them. "He told me in 1985 that there was [sic] two squadrons of Stealth bombers operational in Arizona and I just thought he was crazy," Fiers testified. "It was the, one of the greatest secrets the government had and then all of a sudden we, in fact, ended up with two squadrons of Stealth bombers operational. And there were many, many other instances when he told me things, and I thought they were totally fanciful and, in fact, turned out to be absolute truth."

One of the many surprises North had for Fiers was the fact that he had received specialized training usually reserved for CIA officers. During one late- night conversation about the Contra supply operation in Costa Rica, Fiers testified, North blurted out that he had "put together a whole cascade of cover companies, 'just like they taught us at the CIA clandestine training site.' And I thought that was pretty interesting because I went there and I didn't learn how to put together a whole cascade of companies. And 1 also didn't know that Ollie North had gone down to the training site."

Savvy bureaucrats in Washington knew North was not someone to be taken lightly. Fiers called him "a power figure in the government. . .a force to be reckoned with." When he asked for something, people jumped. When he gave orders, they were followed. "Ollie North had the ability to work down in my chain of command and to cause [it] to override me if and when I didn't do something," Fiers testified. "And, I would like to add, subsequently I saw that happen in other ways, other places and other agencies."

Fiers's boss at the CIA, Clair E. George, echoed that. "I suffer from the bureaucrat's disease, that when people call me and say, 'I am calling from the White House for the National Security Council on behalf of the national security advisor,' I am inclined to snap to."

CIA Costa Rican station chief Joe Fernandez was more blunt. "To a GS-15, this guy talks to God, right?" Fernandez said of North during a secret congressional hearing in 1987. "Obviously, I knew where he worked in the Executive Office Building. He has got tremendous access. . .. I mean, North is not some ordinary American citizen that is suddenly in this position. This is a man who had dealings with, obviously, the Director of the CIA. . .. You know, he deals with my division chief."

North was even telling U.S. ambassadors what to do.

In July 1985, before taking his new job as ambassador to Costa Rica, Lewis Tambs said North sat him down and gave him his marching orders. "Colonel North asked me to go down and open up the Southern Front," Tambs told the Iran-Contra committees. "We would encourage the freedom fighters to fight. And the war was in Nicaragua. The war was not in Costa Rica, and so that is what I understood my instructions were."

But with the CIA's billions officially banned from the scene, North had a big problem if he was going to get the Contras out of their Costa Rican border sanctuaries and into Nicaragua to do some actual fighting.

He had no way to supply them; the CIA had been doing all that.

It takes tons of material to sustain an army in the field, particularly one that is going to be warring deep inside enemy territory, separated by days from its supply depots. The CIA had plenty of experience handling such complicated logistical problems, but North didn't. It was a problem he took up with his friends at Langley, who, according to CIA official Fiers, "spent major time, major effort" trying to come up with a solution.

"Air resupply of the Contras was the key," Fiers testified. "We had a 15,000- man army of guerrillas operating in Nicaragua and had to supply them. All of the supply went by air. They carried in what—their boots and their clothes, and then their new ammunition and such had to be dropped in by air. So the success or failure turned on air resupply operations."

One of the vehicles North selected to handle that chore was a new unit set up inside the U.S. State Department called the Nicaraguan Humanitarian Assistance Office (NHAO). The office was officially created in mid-1985 to oversee the delivery of $27 million in "humanitarian" aid Congress agreed to give the Contras, under considerable pressure from the White House.

North and the CIA first tried to get the operation placed inside the National Security Council, where it would be free from public scrutiny and North could control it directly, but that move failed. Instead, Fiers said, North simply "hijacked" it from the State Department. In November 1985 he pressured the NHAO to hire one of his aides as a consultant, a tall, blond former L.A. prep school counselor named Robert W Owen. A Stanford University grad and onetime advertising executive, Owen idolized North. Since 1984 he had been, in his own words, North's "trusted courier" in Central America, zigzagging through the war zones for Ollie, listening to the concerns of Contra officials, setting up arms deals, and solving problems.

Owen's work had drawn rave reviews from his CIA contacts. "That man has all of the attributes that we want in our officers," Costa Riean station chief Fernandez told Congress during a 1987 hearing. "I met with him on a number of occasions. . .introduced him to one of my officers who regularly met with him when he was in town." Fernandez said his superiors were "so impressed with Mr. Owen that he was being considered as a possible applicant for the clandestine service."

Owen, in 1989 court testimony, admitted that "there was a possibility that I might have gone with the CIA on contract."

But because Owen was a private citizen, Fernandez said, he couldn't legally send him out on intelligence-gathering missions. He could listen when Owen reported back but couldn't, in CIA jargon, "task" him. But that all changed once Owen began working for the NHAO, which probably explains North's insistence that Owen be hired. "When he did that, then we did have a much more operational relationship," Fernandez confirmed. "Because then he was a government employee, I did ask him to find out things."

NHAO director Robert Duemling and his aides couldn't figure out why they needed to have Rob Owen around, and initially they rebuffed North's suggestions. "I certainly didn't see the necessity for a middleman," Duemling testified in a once-secret deposition to the Iran-Contra committees. But North kept pushing. Duemling said North had Contra leaders write letters demanding Owen's hiring, and he lobbied Duemling's superior at the State Department, Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams, a fervent Contra supporter. After one stormy meeting with North and Abrams, Duemling said, "Elliott Abrams turned to me and said, 'Well, Bob, I suppose you probably ought to hire Owen.' Well, in bureaucratic terms the jig was up, since I was the only person who was speaking out against this."

Owen was given a $50,000 contract as a "facilitator," a job that mystified Duemling's aide, Chris Arcos. Arcos testified that no one was "sure what, in fact, Rob Owen could do or bring or offer to the office that we couldn't do. He didn't have much Spanish, he didn't have an expertise in medical or anything like that."

The minutes of that November 1985 meeting show that for some reason, Abrams and North were extremely concerned about the fallout if someone discovered Owen's involvement with the NHAO, and they began working on a cover story to explain his presence there in case it leaked. "Abrams and North agreed that Owen will be expendable if he becomes a political or diplomatic liability," the minutes state. If that happened, Congress would be told that he was "an experiment that hadn't worked out."

It was an experiment right out of Dr. Frankenstein's lab.

Rob Owen's mission was to serve as the CIA's unofficial liaison to the drug traffickers and other undesirables who were helping the Contras in Costa Rica, people who were too dirty for the CIA to deal with directly. Like North, he was another "cutout." "He probably had the most extensive network of contacts among the resistance leaders," CIA station chief Fernandez testified in 1987, "including people with whom we did not want to have contact with and who, however, were involved with the Nicaraguan resistance."

The untouchables Fernandez was referring to were the Cuban anti¬ communists in Costa Rica—the rough mix of mercenaries, bombers, assassins, and drug dealers recruited in Miami by UDN-FARN commander Fernando "El Negro" Chamorro and CIA agent Ernesto Cruche. The agency, Fernandez testified, was "very leery of these people. I however, Rob Owen had an entree to them."

And now, thanks to his NHAO job, he had an official entree—as an operational CIA asset. Owen's specific assignment, in fact, put him directly over the drug traffickers Fernandez and the CIA didn't want to be seen with.

He was assigned to "monitor" an NHAO contract with a Costa Rican shrimp company called Frigorificos de Puntarenas, S.A. This consisted of a small fleet of fishing boats based in the humid Pacific Coast village of Puntarenas, and an import company in Miami called Ocean Hunter, which brought Frigorificos' catch into the United States. In reality, however, it was "a firm owned and operated by Cuban-American drug traffickers," according to a 1988 Senate subcommittee report.

That conclusion was based partly on the congressional testimony of former Medellin cartel accountant Ramon Milian Rodriguez, a suave Cuban-American who was the cartel's money-laundering wizard until his arrest in Miami in 1983, when he and $5 million in cash were taken off a Lear jet bound for Panama. Frigorificos, he testified, was one of an interlocking chain of companies he'd created to launder the torrents of cash that were pouring into the cartel's coffers from its worldwide cocaine sales. Drug money would go into one company and come out of another through a series of intercompany transactions, clean and ready to be banked or invested. In 1982, Frigorificos was taken over by a group of major Miami-based drug traffickers, who began using it to help the Contras.

"Were payments or arrangements made by which the Contras could receive money through Frigorificos?" Senator John Kerry asked Milian during a Senate subcommittee hearing in 1987.

"Yes sir," the accountant answered.

"You arranged that?"

"I, through my intermediaries, made it possible."

"Was any of the money that you provided Frigorificos traceable to drugs or to drug-related transactions?" Kerry asked.

"No, sir."

"Why was that?"

"Because," said Milian, "we were experts at what we do."

Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras ..., by Gary Webb

22 posts

• Page 3 of 3 • 1, 2, 3

Re: Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras ..., by Gary Webb

Part 2 of 2

"El Rey de la Droga" (The King of Drugs), Norwin Meneses Cantarero, during an interview with the author and Georg Hodel at Tipitapa Prison outside Managua in 1996. PHOTO BY GARY WEBB

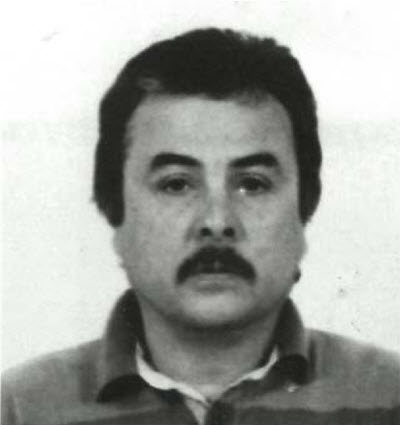

FDN supporter Don Sinicco snapped this picture in his kitchen in San Francisco during a cocktail party he was hosting for CIA agent Adolfo Calero, center. Drug lord Norwin Meneses is on the far right. The other men are local Contra supporters. At the time this photo was taken, June 1984, Meneses was engaged in a cocaine smuggling conspiracy, according to federal prosecutors, photo. COURTESY OF DON SINICCO

Danilo Blandon, circa 1995.

ABC Park and Fly, near the Miami International Airport. Blandon established his car rental company in this building during his brief "retirement" from the cocaine business in 1987. The day this picture was taken Anastasio Somoza's former counterinsurgency expert, Maj. Gen. Gustavo "El Tigre" Medina, was working behind the counter, Photo by Gary Webb

Enrique Miranda Jaime, shortly after the FBI kidnapped him in Miami and sent him back to Nicaragua to face escape charges in late 1996. Miranda, a former double agent for the CIA and the Sandinistas, was Meneses's top aide after the war and would later help send his boss to prison, photo by Gary Webb

Former Contra cocaine courier Carlos Cabezas, at his law office in Managua. PHOTO BY GARY WEBB

The Oval Office, August 5, 1987. A gathering of Nicaraguan resistance leaders to mark yet another CIA-inspired merger of the Contra armies from the FDN to the United Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO). Second from left is Aristides Sanchez. Adolfo Calero is on the far right, courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library.

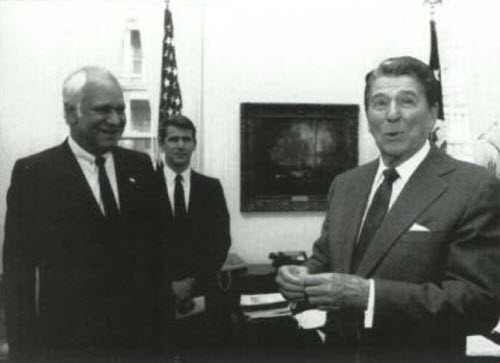

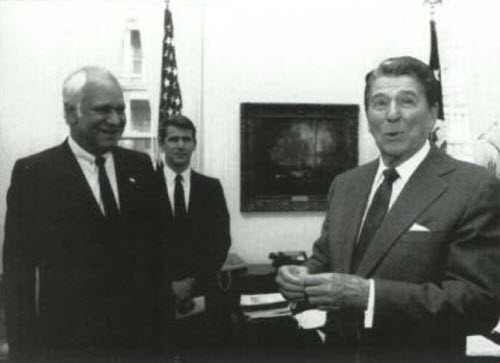

The Oval Office, April 4, 1985. From left: CIA agent Adolfo Calero, political boss of the FDN; Lt. Col. Oliver North and President Ronald Reagan, after the CIA handed off the day-to-day management of the Contra project to North and the National Security Council, courtesy of the Ronald Reagan library

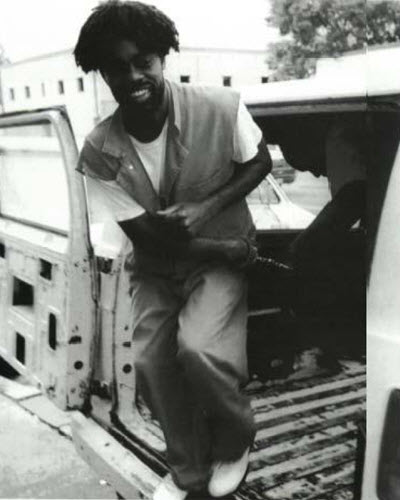

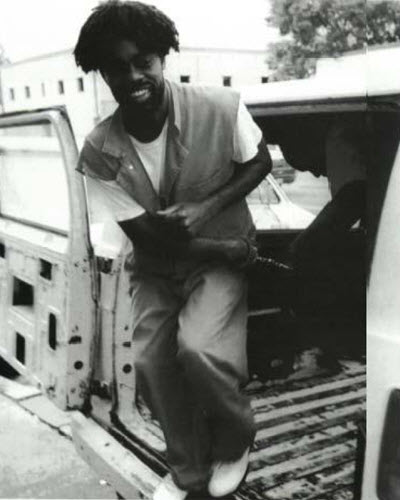

L.A. crack kingpin "Freeway" Ricky Ross was all smiles as he was released from a Texas prison in 1994 after serving a short stint for cocaine trafficking. Though he had vowed to go straight, a few months later he would be lured back into the drug business by his old friend and cocaine supplier, Danilo Blandon. ROBERT GAUTHIER/LOS ANGELES TIMES

Ricky Ross was captured March 2,1995 in National City after his truck careened into a hedgerow, photo by Gary Webb

Part of the $160,000 seized by the DEA from crack dealer Leroy "Chico" Brown during the 1995 sting that snared "Freeway" Ricky Ross, DEA photo

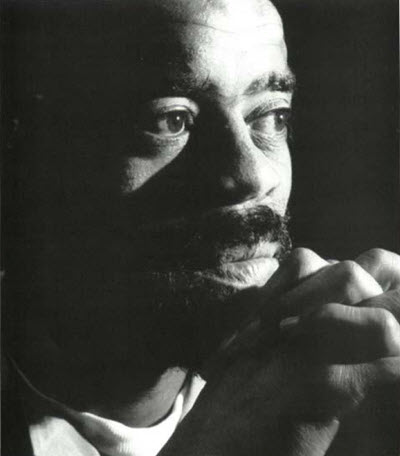

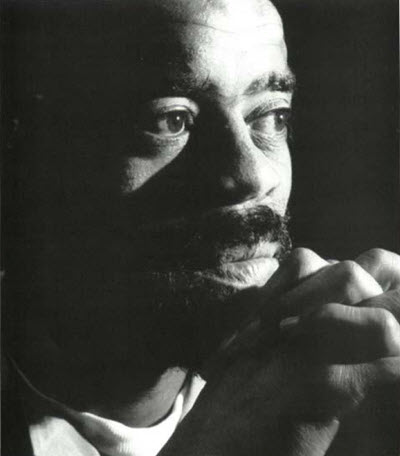

Ricky Donnell Ross, shortly before he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in October 1996. Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times

Milian, a graduate of Santa Clara University in Silicon Valley, told Kerry's committee that he used the firm to launder a $10 million donation from the Medellin cartel to the Contras, a donation he said was arranged by and paid to a former CIA agent, Cuban Felix Rodriguez. Kerry's committee didn't believe that tale, especially after Milian flunked a lie detector test on the question.

But during the drug trafficking trial of Manuel Noriega several years later, one of the government's star witnesses, former Medellin cartel transportation boss Carlos Lehder, confirmed under oath that the cartel had given the Contras $10 million, just as Milian had testified. Lehder said he arranged for the donation himself.

Contra leader Adolfo Calero has always denied the Contras received such a sum, but Calero is hardly a credible source when it comes to Contra fund¬ raising. I le denied for many years that the Contras ever got money from the CIA, or assistance from Oliver North.

The FBI first picked up word of Frigorificos' involvement with drugs in September 1984, while the CIA was still running the Contra program. An investigation of a 1983 bombing of a Miami bank had led police and FBI agents into the murky underworld of Miami's Cuban anti-Communist groups, who were suspected of blowing up the bank.

Miami police questioned the president of the Cuban Legion, Jose Coutin, who told them what he knew of the bombing and then unloaded some unexpected information about the Contras and drugs, naming a host of Cuban CIA operatives and Bay of Pigs veterans he said were working for the Contras in Costa Rica. One drug dealer Coutin named was Francisco Chanes, whom Coutin said "was giving financial support to anti-Castro groups and the Nicaraguan Contra guerrillas. The monies come from narcotic transactions." lie identified Chanes as one of the owners of Ocean Hunter, the sister company of Frigorificos. The Miami cops quickly turned the information over to the FBI, records show.

Coutin's statements were corroborated years later by former drug pilot Fabio Ernesto Carrasco, who admitted flying cocaine and weapons loads for the Contras in 1984 and 1985. As a U.S. government witness, Carrasco testified that Frigorificos was being used by the Contras during the war as a front to bring cocaine into the United States to finance the war effort.

"To make sure I understand, is this company Frigorificos de Puntarenas in any way involved in drug trafficking?" defense attorney Richard "Racehorse" Haynes asked Carrasco during a 1990 drug trial in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

"That's correct."

"In what way was it involved?"

"As I have said, they would load cocaine inside the containers which were being shipped loaded with vegetables and fruit to the United States," Carrasco said.

"Did this company have a role in your drug operations dealing with the Contras and the weapons that you believed to be involved with the CIA?"

"It did in my opinion," the pilot testified.

So how could a company started by the Medellin cartel and used as a front to run drugs into America ever wind up with a contract from the U.S. State Department's Nicaraguan Humanitarian Assistance Office?

Through Rob Owen and the CIA, court records show.

"The people that were involved in Ocean Hunter in Costa Rica were ones that had been helpful to the cause," Owen testified in a 1988 civil deposition. He identified those helpful souls as Frank Chanes, the Miami Cuban who was reported to the FBI as a drug trafficker in 1984, and Moises Nunez, another Bay of Pigs veteran who was suspected by Interpol of being a drug trafficker as well as an intelligence operative.

Another man involved with Frigorificos was the exiled Nicaraguan lawyer Francisco Aviles Saenz, the CIA asset who claimed the $36,000 police had seized during the investigation of the Frogman case in San Francisco in 1983 belonged to the Contras. On several occasions Aviles, the brother-in-law of Meneses's lieutenant Horacio Pereira, notarized affidavits submitted by the shrimp company to obtain payment from the State Department, records show.

Owen claimed the shrimp company was used mainly for its international bank accounts, serving as one of several Central American "brokers" for the humanitarian aid money going to the Contras on the Southern Front. In all, more than $260,000 in U.S. taxpayer funds flowed through Frigorificos's bank accounts during 1986.

"We needed an account in Miami that the [State Department] money could be deposited to. [There were] constant financial transactions between Miami and Costa Rica, between Frank Chanes and Moises Nunez. They had been helpful and supportive of the cause. They were willing to do it," Owen testified. "I felt that they were honest and that the money would go where it was supposed to go."

Where it ended up is anybody's guess. Some of the money paid Frigorificos, bank records show, was wired out in never-explained transfers to banks in Israel and South Korea. When the U.S. General Accounting Office audited the NHAO's "broker" accounts, it was unable to trace most of the money. Of $4.4 million that went into the accounts, less than $1 million could be accounted for, and much of that was in payoffs to Honduran military officials. The rest was traced to offshore banks and then disappeared.

Owen insisted that the traffickers at Frigorificos had been cleared by the CIA and presumably the FBI. "U.S. intelligence sources were involved in Costa Rica to provide a check and a balance on this. They would be knowledgeable, they knew the lay of the ground. I thought it important and appropriate to talk with them," Owen testified. "To the best of my knowledge, I talked to U.S. intelligence officials regarding Moises Nunez. I believe I would have asked about Frank Chanes as well."

In addition, Owen said, "their names were given to NHAO and it was my understanding that any account that NHAO provided funds to was checked through the FBI. The FBI was informed who was being used as a banker. Now, whether they did any check on it or not, I'm not sure. I guess I assume that they did."

The director of the NHAO testified that the FBI never answered his letters of inquiry.

"So, is it fair to say, then, that you were the one that suggested these gentlemen be utilized?" Owen was asked during a deposition.

"It is fair to say. . .in consultation with U.S. intelligence officials," Owen replied. Owen refused to identify them further, other than to say that it was "someone who works for the CIA."

One reason the CIA gave Frigorificos a clean bill of health may have been because its Costa Rican manager, Moises Nunez, was a CIA agent. John Hull, the CIA's Costa Rican liaison with the Contras, confirmed in an interview that Nunez was working with the agency as an intelligence source, and a 1988 UPI story said Nunez was "identified as an Agency officer by two senior Costa Rican government officials, a U.S. intelligence source, and American law enforcement authorities."

In addition to distributing State Department money to the Costa Rican Contras, Nunez was also permitting Frigorificos to be used by North and CIA station chief Fernandez as a cover for a secret maritime operation they were running against the Sandinistas, records show.

In February 1986, one of the Cubans working with North in Costa Rica, a longtime CIA contract agent named Felipe Vidal, devised a plan for a "small, professionally managed rebel naval force" that would serve as a supply line for the Contras, an intelligence-gathering operation, and a transportation unit "to infiltrate into the [Nicaraguan] mainland rebel cadres for specific missions."

Vidal recommended using a Costa Rican shrimp company as "a front" and getting two shrimp boats to act as motherships and to gather intelligence. "These boats could be acquired from U.S. government auctions," Vidal wrote, noting that "existing connections with a high-ranking official in the DEA would facilitate the purchase of said boats. The cost of these boats, with cooperation from the DEA, could come to as low as $10,000 per boat." CIA records show that Vidal was employed by Frigorificos at the time he proposed this scheme.

Vidal's "existing connections" with a top DEA official are fascinating, considering the Cuban's shady background. Vidal's criminal history "reflects an assortment of assault, robbery, narcotics, and firearms violations," the CIA Inspector General wrote, and included a 1971 drug conviction and a 1977 arrest for conspiracy to sell marijuana. Former CIA official Alan Fiers admits being aware of Vidal's "record of misbehavior and general thuggery" but claims he didn't know the Cuban was a convicted drug trafficker. The following month, Owen informed North that "the first hard intelligence mission inside by boat has taken place and the people arc now out." He said five small boats were being constructed and "a safe house [in Costa Rica] has been rented on a river, which flows into the ocean."

"Moises Nunez, a Cuban who has a shrimping business in Punteranous [sic] is fronting the operation," Owen wrote North. "He is willing to have an American come work for him under cover to advise the operation. ... If we can get two shrimp boats, Nunez is willing to front a shrimping operation on the Atlantic coast. These boats can be used as motherships. I brought this up awhile ago and you agreed and gave me the name of a DEA person who might help with the boats."

In other words, in early 1986 the DEA was being asked to provide cheap oceangoing vessels to a company started by the Medellin cartel, run by drug traffickers, for espionage missions planned and fronted by drug traffickers.

The identity of Vidal's high-ranking DEA contact was not divulged, nor is it known whether the agency ever provided the boats, but records show the maritime operation was going strong in April 1986 and would soon be running "several trips a week," according to a memo Owen sent to North. Curiously, the Iran-Contra investigations barely looked at this clandestine operation, which was a clear violation of the Boland Amendment since, according to Owen, it directly involved CIA station chief Joe Fernandez.

Despite his background, Moises Nunez also maintained a chummy relationship with antidrug agencies, both American and Costa Rican. "Nunez got to be known by our authorities as a collaborator of the DEA and of other police bodies," said a 1989 Costa Rican prosecutor's report, adding that the Cuban carried credentials from the Costa Rican Ministry of Public Safety's Department of Narcotics, provided funds and vehicles for an antidrug unit, and went out on raids with them, though his effectiveness was somewhat questionable. The report said he blew a four-month investigation of a Colombian drug ring by making a "premature" arrest.

Most of this strange activity was occurring with the knowledge and apparent approval of CIA station chief Fernandez and other CIA agents in Costa Rica, records indicate. Fernandez admitted to the Iran-Contra committees that he knew Nunez and knew he was meeting with Owen to discuss Contra operations. Fernandez was asked if he knew that Nunez claimed to have met North, but his answer was classified for reasons of national security.

Nunez, however, shed light on that question when the CIA interrogated him in March 1987 about allegations that he'd been dealing drugs in Costa Rica through his shrimp company, Frigorificos. Thanks to a DEA seizure, the CIA already knew that Nunez's partners in that firm were behind a 414-pound cocaine load shipped to Miami in January 1986 amidst crates of yucca.

"Nunez revealed that since 1985, he had engaged in a clandestine relationship with the National Security Council [NSC]," the CIA Inspector General reported. "Nunez refused to elaborate on the nature of these actions but indicated it was difficult to answer questions relating to his involvement in narcotics trafficking because of the specific tasks he had performed at the direction of the NSC."

Instead of following up on this eyebrow-raising answer, CIA headquarters ordered an immediate halt to Nunez's questioning. "The Agency position was not to get involved in this matter and to turn it over to others because it had nothing to do with the Agency, but with the National Security Council," former CIA officer Louis Dupart reasoned in an interview with the CIA Inspector General. "That's all we had to do. It was someone else's problem." That "someone" was harried Iran-Contra prosecutor Lawrence Walsh, upon whom every potential allegation of drug trafficking by the Contras was dumped by the CIA and the Reagan Administration. Of course, Walsh had neither the time nor the authority to look into most of those leads and the CIA refused to cooperate on the few occasions when he did ask some questions. Therefore he made an excellent scapegoat in case anyone wondered why tips about drug dealing by the NSC and the Contras were never investigated. "We turned it over to Lawrence Walsh," became the Agency's standard reply.

Former CIA official Alan Fiers, who ran the Contra project at the time, confirmed that Nunez's questioning was stopped "because of the NSC connection and the possibility that this could be somehow connected to [North's] Private Benefactor program, otherwise known as the Iran-Contra affair."

The CIA made the same decision when a security check on the CIA's logistics advisor to the Costa Rican Contras, Cuban mercenary Felipe Vidal, discovered evidence of drug running.

"Narcotics trafficking relative to Contra-related activities is exactly the sort of thing that the U.S. Attorney's Office will be investigating," CIA attorney Gary Chase worried in an August 1987 memo. Chase "expressed concern over the possibility that the security process. . .could be exposed during any future litigation." Vidal's security check was shut down.

But the Agency's conduct was far worse than simply burying its head in the sand. For years afterward, it shielded both Dago Nunez and Felipe Vidal from criminal investigations into drug trafficking and money laundering. At various times, the CIA told U.S. Customs and the DEA that it had no information about Nunez's trafficking activities. The CIA's Directorate of Operations—which runs covert operations—lied even to the Agency's own lawyers, denying knowledge of Nunez's shrimp company though there was plenty of information in its files.

Fiers also confirmed that the CIA played a critical role in the "humanitarian" aid operation involving Frigorificos; without the agency, Fiers said, the NHAO was simply "a shell entity. . .. We were to be the eyes and ears of the NHAO office. The only way that they could monitor alignments, verify shipments and receipts was by having CIA capabilities in the region perform that function for them. And so that's what we did." But since at least three other drug-dealing companies ended up working for the NHAO during its brief lifespan, either the CIA's oversight was woefully incompetent or it was seeking a special kind of contractor.

One such company was DIACSA, the Miami aircraft company that Floyd Carlton had used for years as the U.S. headquarters for his Panamanian drug¬ smuggling venture with Noriega. It was in DIACSA's offices, Carlton admitted, that he and his partners plotted their drug flights and arranged the laundering of their cocaine profits. DEA records confirm that.

Just like Frigorificos, DIACSA was run by a Cuban drug dealer who had been part of the CIA's Bay of Pigs operation, Alfredo Caballero. Carlton testified that Cabellero was "involved with drug trafficking and to a certain extent he helped the Contras. But to be more specific he was helpful to Mr. Pastora's organization [ARDE]."

According to a Senate subcommittee report, the Contras were dealing with DIACSA even before it was hired by the State Department. "During 1984 and 1985, the principal Contra organization, the FDN, chose DIACSA for 'infra¬ account transfers.' The laundering of the money through DIACSA concealed the fact that some funds of the Contras were deposits arranged by Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North," the report stated.

The State Department's selection of DIACSA as a "humanitarian" aid contractor is perhaps even more egregious than its choice of Frigorificos. At the time DIACSA got its government contract, the company had been penetrated by an undercover DEA agent, Danny Moritz, who was churning out eyewitness reports of Caballero's drug dealing and money-laundering rackets. Moreover, both Caballero and Carlton were under indictment in the United States for conspiring to import 900 pounds of cocaine and laundering $2.6 million in drug profits. Both were convicted, and both became U.S. government informants.

How the CIA missed those clues has never been explained. It is highly likely the agency knew exactly what DIACSA was, since its owner was said to be working for the CIA. "Alfredo Caballero was CIA and still is," insisted Carol Prado, Eden Pastora's top aide in ARDE. "I say that because I knew him very well. A lot of times I went to DIACSA in Miami." Prado has reason to know. A 1985 CIA cable described DIACSA as the "cover company" used by the Costa Rican Contras to secretly buy aircraft.

During Noriega's trial in 1991, Floyd Carlton testified that his smuggling operation was flying weapons to the Contras at the same time he was flying dope to the United States and he said some of the arms flights were organized by Caballero. When Noriega's lawyers asked Carlton about Oliver North's knowledge of those flights, federal prosecutors vehemently objected, and U.S. judge William Hoeveler became angry. "Just stay away from it," the judge snapped, refusing to allow any more questions on the topic.

Another Miami company the NHAO hired to ferry supplies was Vortex Aviation, which was being operated by a Detroit drug dealer named Michael Palmer. Palmer, a former airline pilot, had worked since 1977 for "the largest marijuana business cartel in the history of the country," according to a federal prosecutor in Detroit. Yet in 1985 Palmer became a freedom fighter and volunteered for the Contra war effort, transporting humanitarian aid for the State Department.

In a recently declassified interview with FBI agents in 1991, CIA official Fiers admitted that the CIA had information that Palmer was dealing drugs during that time. "Fiers heard that sonic of Palmer's people got caught taking a plane of drugs into the U.S. and this is what caused a lot of problems for Palmer," the FBI reported. "CIA thought the northern Contras were clean but Palmer was an exception."

One DC-4 Palmer was using to deliver Contra aid was shot up in February 1986 as it attempted an airdrop over Nicaragua, and it made an emergency landing on San Andres Island off the coast of Nicaragua, a notorious haven for cocaine traffickers. Four days later Owen wrote to North, saying, "No doubt you know that the DC-4 Foley got was used at one time to run drugs and part of the crew had criminal records. Nice group the Boys chose." Pat Foley was the owner of a Delaware-based company, Summit Aviation, a longtime CIA and U.S. military contractor, often for clandestine air operations. Foley was reportedly overseeing Palmer's operations at Vortex.

Francis McNeil, at the time one of the State Department's top narcotics intelligence officers, confirmed to Congress that the DC-4's appearance at San Andres caused red flags to go up in Washington. "A stop at San Andres Island for a Contra resupply plane is a bit suspicious since San Andres is known to be a transshipment point for drugs," McNeil testified.

The pilot of that unlucky DC-4, former CIA contract pilot Ronald Lippert, said in an interview that neither his trip nor his crew were involved with drugs, though the plane had been involved with drug flights "long before I acquired it." He said the landing at San Andres was for repairs only. But he acknowledged that his plane was probably used for drug flights while Vortex was hauling humanitarian aid for the Contras. Those flights were piloted by Vortex's own crews, Lippert said. He knew one of the flights wound up in Colombia, because he got a call from the FAA in Miami "asking what my plane was doing, taking off from a dirt strip on the northeast coast of Colombia during its two-day mysterious absence on the Nicaraguan Contra flight."

Lippert, a Canadian who flew for the CIA in the early 1960s until his imprisonment by Cuban intelligence agents in 1963 for espionage, said that "the most I was able to find out from a friend in the intelligence community was the name 'Operation Stolen Mercedes' and that aside from Costa Rica, its itinerary may have included a stop in Panama and Mexico after it left Colombia."

On another Contra flight, Lippert's plane came back with an unexplained twelve and a half hours of excess flying time on it; Palmer told him the pilots had to make an emergency detour to Costa Rica. In his testimony to the Iran- Contra committees, Rob Owen confirmed that the airplane was involved in an unexplained "embarrassing situation" in Costa Rica. "That's when 1 decided some real strange shit was happening," Lippert said. "It came back all messed up with bullet holes in the tail and the engine burned out and, after that, I told them that was it. Unless I'm flying the plane, it was no dice. So Palmer says, 'Fine, I'll buy the damned thing from you.'"

Palmer, whom the CIA admits was working as an Agency subcontractor at this point, arranged to buy Lippert's DC-4 through some associates of his: a Cuban lawyer from Miami named Jose Insua and an aircraft company executive, Richard Kelley, both of whom intimated to Lippert that they were working with the CIA. After the sale, Lippert said, the DC-4 was used to airdrop explosives off the coast of Cuba. Then, a month after he signed the installment sale papers, it was seized in Mexico with 2,500 pounds of marijuana on board.

A story in the Mexican newpaper La Opinion quoted the attorney general of Mexico as saying that the plane was being used by a "powerful gang of drug- smugglers. . .known to have been operating for a long time using large aircraft to transport arms southbound and bring back marijuana through here."

Lippert never got the plane back, nor was he ever paid for it. The company that issued the letters of credit that "guaranteed" the purchase of his plane was later shut down by the state of Florida, which announced that its owners were drug traffickers and fugitive stock swindlers. "Can't we close a bank or even a supposed bank anymore without finding some sort of tie to the Contras?" bank examiner Barry Cladden wondered to a Miami Herald reporter in 1987. "What's the world coming to?"

One of the DC-4's buyers, Jose Insua, was later exposed as a drug trafficker and DMA informant himself, and was used by the agency in an unsuccessful attempt to snare the former chairman of the Florida Democratic party in a bribery sting. During the trial, the government admitted that Insua was "involved in the brokering of aircraft for narcotics smugglers on approximately 12 occasions."

As Lippert aptly observed in 1997, "Jose Insua is a drug dealer and he's hanging around a company [Vortex] with a State Department eon-tract. Michael Zapcdis is a drug dealer and he issues two letters of credit for planes that are used by the CIA. Mike Palmer is a drug dealer and he's running an airline for the CIA. You tell me what's going on."

Actually, the litany of drug dealers working for Vortex was even longer than that, according to the CIA's Inspector General. "Michael Palmer, Joseph Haas, Alberto Prado Herreros, Mauricio Letona, Martin Gomez, Donaldo Frixone, and two pilots for the prime contractor—all of whom were affiliated with the CIA Contra support program—may have been involved in narcotics trafficking prior to their relationship with the Agency," the Inspector General found.

Records show top CIA officials were fully aware that Vortex was dabbling in drugs even before they recommended the company for the NHAO's "humanitarian aid" project and, later, for a CIA subcontract.

"At least two Agency officers [Alan Fiers and an unnamed CIA contractor] knew about Palmer's drug dealing before the Agency agreed to buy an aircraft from Vortex and approved the subcontracting to Vortex of the servicing of aircraft flying resupply flights for the Contras," a May 1988 CIA memo states.

The NHAO also hired a Honduran air freight company, SETCO, which happened to be owned by the Honduran drug kingpin Juan Matta Ballesteros, a fact that the U.S. Customs Service had known since 1983. "SETCO was the principal company used by the Contras in Honduras to transport supplies and personnel for the FDN," the CIA's Inspector General reported. "[Oliver] North also used SETCO for airdrops of military supplies to Contra forces inside Nicaragua." In fact, that appears to have been the reason behind all of the State Department contracts that were awarded to cocaine smugglers: they were the same people the CIA had hired to do that work when the agency was running the show.

"I believe we guided them toward the carriers they ultimately used," former CIA official Alan Fiers confirmed in 1998. Fiers told CIA interviewers in 1987 that he and NHAO director Robert Duemling "had frequent meetings regarding possible contract cargo carriers. . .[Fiers] said he had checked out some of these carriers for Duemling."

Duemling told Iran-Contra investigators that he was given very specific instructions regarding the cargo carriers when he took over the humanitarian aid program. "One of the policy guidelines was do not disrupt the existing arrangements of the resistance movement unless there is a terribly good reason," Duemling testified.

"Who told you that, by the way, going back to the beginning of this?"

"Ollie North," Duemling said. He said North instructed him not to "dislodge or replace their existing arrangements, which seemed to be working perfectly well."

They certainly were, in one sense. According to Danilo Blandon's lawyer, Brad Brunon, the Centra's cocaine was arriving in the United States literally by the planeload. "The transportation channel got established and got filled up with cocaine rather quickly," Brunon said in an interview. "As I understood it, these large transports were coming back from delivering food and guns and humanitarian aid and things like that and they were just loading them up with cocaine and bringing them back. I think 1,000-kilo shipments were not unheard of. That scale. Because all of a sudden they seemed to have unlimited sources of supply."

According to former Meneses aide Enrique Miranda, Meneses's drug-laden planes were flying out of a military air base in El Salvador called Ilopango. Like the CIA before him, North had selected that base as the hub for his Contra air force; his operatives worked there "practically unfettered," according to the report of Iran-Contra prosecutor Lawrence Walsh.

And it was at Ilopango where the whole sordid mess first started to unravel.

"El Rey de la Droga" (The King of Drugs), Norwin Meneses Cantarero, during an interview with the author and Georg Hodel at Tipitapa Prison outside Managua in 1996. PHOTO BY GARY WEBB

FDN supporter Don Sinicco snapped this picture in his kitchen in San Francisco during a cocktail party he was hosting for CIA agent Adolfo Calero, center. Drug lord Norwin Meneses is on the far right. The other men are local Contra supporters. At the time this photo was taken, June 1984, Meneses was engaged in a cocaine smuggling conspiracy, according to federal prosecutors, photo. COURTESY OF DON SINICCO

Danilo Blandon, circa 1995.

ABC Park and Fly, near the Miami International Airport. Blandon established his car rental company in this building during his brief "retirement" from the cocaine business in 1987. The day this picture was taken Anastasio Somoza's former counterinsurgency expert, Maj. Gen. Gustavo "El Tigre" Medina, was working behind the counter, Photo by Gary Webb

Enrique Miranda Jaime, shortly after the FBI kidnapped him in Miami and sent him back to Nicaragua to face escape charges in late 1996. Miranda, a former double agent for the CIA and the Sandinistas, was Meneses's top aide after the war and would later help send his boss to prison, photo by Gary Webb

Former Contra cocaine courier Carlos Cabezas, at his law office in Managua. PHOTO BY GARY WEBB

The Oval Office, August 5, 1987. A gathering of Nicaraguan resistance leaders to mark yet another CIA-inspired merger of the Contra armies from the FDN to the United Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO). Second from left is Aristides Sanchez. Adolfo Calero is on the far right, courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library.

The Oval Office, April 4, 1985. From left: CIA agent Adolfo Calero, political boss of the FDN; Lt. Col. Oliver North and President Ronald Reagan, after the CIA handed off the day-to-day management of the Contra project to North and the National Security Council, courtesy of the Ronald Reagan library

L.A. crack kingpin "Freeway" Ricky Ross was all smiles as he was released from a Texas prison in 1994 after serving a short stint for cocaine trafficking. Though he had vowed to go straight, a few months later he would be lured back into the drug business by his old friend and cocaine supplier, Danilo Blandon. ROBERT GAUTHIER/LOS ANGELES TIMES

Ricky Ross was captured March 2,1995 in National City after his truck careened into a hedgerow, photo by Gary Webb

Part of the $160,000 seized by the DEA from crack dealer Leroy "Chico" Brown during the 1995 sting that snared "Freeway" Ricky Ross, DEA photo

Ricky Donnell Ross, shortly before he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in October 1996. Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times

Milian, a graduate of Santa Clara University in Silicon Valley, told Kerry's committee that he used the firm to launder a $10 million donation from the Medellin cartel to the Contras, a donation he said was arranged by and paid to a former CIA agent, Cuban Felix Rodriguez. Kerry's committee didn't believe that tale, especially after Milian flunked a lie detector test on the question.

But during the drug trafficking trial of Manuel Noriega several years later, one of the government's star witnesses, former Medellin cartel transportation boss Carlos Lehder, confirmed under oath that the cartel had given the Contras $10 million, just as Milian had testified. Lehder said he arranged for the donation himself.

Contra leader Adolfo Calero has always denied the Contras received such a sum, but Calero is hardly a credible source when it comes to Contra fund¬ raising. I le denied for many years that the Contras ever got money from the CIA, or assistance from Oliver North.

The FBI first picked up word of Frigorificos' involvement with drugs in September 1984, while the CIA was still running the Contra program. An investigation of a 1983 bombing of a Miami bank had led police and FBI agents into the murky underworld of Miami's Cuban anti-Communist groups, who were suspected of blowing up the bank.

Miami police questioned the president of the Cuban Legion, Jose Coutin, who told them what he knew of the bombing and then unloaded some unexpected information about the Contras and drugs, naming a host of Cuban CIA operatives and Bay of Pigs veterans he said were working for the Contras in Costa Rica. One drug dealer Coutin named was Francisco Chanes, whom Coutin said "was giving financial support to anti-Castro groups and the Nicaraguan Contra guerrillas. The monies come from narcotic transactions." lie identified Chanes as one of the owners of Ocean Hunter, the sister company of Frigorificos. The Miami cops quickly turned the information over to the FBI, records show.

Coutin's statements were corroborated years later by former drug pilot Fabio Ernesto Carrasco, who admitted flying cocaine and weapons loads for the Contras in 1984 and 1985. As a U.S. government witness, Carrasco testified that Frigorificos was being used by the Contras during the war as a front to bring cocaine into the United States to finance the war effort.

"To make sure I understand, is this company Frigorificos de Puntarenas in any way involved in drug trafficking?" defense attorney Richard "Racehorse" Haynes asked Carrasco during a 1990 drug trial in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

"That's correct."

"In what way was it involved?"

"As I have said, they would load cocaine inside the containers which were being shipped loaded with vegetables and fruit to the United States," Carrasco said.

"Did this company have a role in your drug operations dealing with the Contras and the weapons that you believed to be involved with the CIA?"

"It did in my opinion," the pilot testified.

So how could a company started by the Medellin cartel and used as a front to run drugs into America ever wind up with a contract from the U.S. State Department's Nicaraguan Humanitarian Assistance Office?

Through Rob Owen and the CIA, court records show.

"The people that were involved in Ocean Hunter in Costa Rica were ones that had been helpful to the cause," Owen testified in a 1988 civil deposition. He identified those helpful souls as Frank Chanes, the Miami Cuban who was reported to the FBI as a drug trafficker in 1984, and Moises Nunez, another Bay of Pigs veteran who was suspected by Interpol of being a drug trafficker as well as an intelligence operative.

Another man involved with Frigorificos was the exiled Nicaraguan lawyer Francisco Aviles Saenz, the CIA asset who claimed the $36,000 police had seized during the investigation of the Frogman case in San Francisco in 1983 belonged to the Contras. On several occasions Aviles, the brother-in-law of Meneses's lieutenant Horacio Pereira, notarized affidavits submitted by the shrimp company to obtain payment from the State Department, records show.

Owen claimed the shrimp company was used mainly for its international bank accounts, serving as one of several Central American "brokers" for the humanitarian aid money going to the Contras on the Southern Front. In all, more than $260,000 in U.S. taxpayer funds flowed through Frigorificos's bank accounts during 1986.

"We needed an account in Miami that the [State Department] money could be deposited to. [There were] constant financial transactions between Miami and Costa Rica, between Frank Chanes and Moises Nunez. They had been helpful and supportive of the cause. They were willing to do it," Owen testified. "I felt that they were honest and that the money would go where it was supposed to go."

Where it ended up is anybody's guess. Some of the money paid Frigorificos, bank records show, was wired out in never-explained transfers to banks in Israel and South Korea. When the U.S. General Accounting Office audited the NHAO's "broker" accounts, it was unable to trace most of the money. Of $4.4 million that went into the accounts, less than $1 million could be accounted for, and much of that was in payoffs to Honduran military officials. The rest was traced to offshore banks and then disappeared.

Owen insisted that the traffickers at Frigorificos had been cleared by the CIA and presumably the FBI. "U.S. intelligence sources were involved in Costa Rica to provide a check and a balance on this. They would be knowledgeable, they knew the lay of the ground. I thought it important and appropriate to talk with them," Owen testified. "To the best of my knowledge, I talked to U.S. intelligence officials regarding Moises Nunez. I believe I would have asked about Frank Chanes as well."

In addition, Owen said, "their names were given to NHAO and it was my understanding that any account that NHAO provided funds to was checked through the FBI. The FBI was informed who was being used as a banker. Now, whether they did any check on it or not, I'm not sure. I guess I assume that they did."

The director of the NHAO testified that the FBI never answered his letters of inquiry.

"So, is it fair to say, then, that you were the one that suggested these gentlemen be utilized?" Owen was asked during a deposition.

"It is fair to say. . .in consultation with U.S. intelligence officials," Owen replied. Owen refused to identify them further, other than to say that it was "someone who works for the CIA."

One reason the CIA gave Frigorificos a clean bill of health may have been because its Costa Rican manager, Moises Nunez, was a CIA agent. John Hull, the CIA's Costa Rican liaison with the Contras, confirmed in an interview that Nunez was working with the agency as an intelligence source, and a 1988 UPI story said Nunez was "identified as an Agency officer by two senior Costa Rican government officials, a U.S. intelligence source, and American law enforcement authorities."

In addition to distributing State Department money to the Costa Rican Contras, Nunez was also permitting Frigorificos to be used by North and CIA station chief Fernandez as a cover for a secret maritime operation they were running against the Sandinistas, records show.

In February 1986, one of the Cubans working with North in Costa Rica, a longtime CIA contract agent named Felipe Vidal, devised a plan for a "small, professionally managed rebel naval force" that would serve as a supply line for the Contras, an intelligence-gathering operation, and a transportation unit "to infiltrate into the [Nicaraguan] mainland rebel cadres for specific missions."

Vidal recommended using a Costa Rican shrimp company as "a front" and getting two shrimp boats to act as motherships and to gather intelligence. "These boats could be acquired from U.S. government auctions," Vidal wrote, noting that "existing connections with a high-ranking official in the DEA would facilitate the purchase of said boats. The cost of these boats, with cooperation from the DEA, could come to as low as $10,000 per boat." CIA records show that Vidal was employed by Frigorificos at the time he proposed this scheme.

Vidal's "existing connections" with a top DEA official are fascinating, considering the Cuban's shady background. Vidal's criminal history "reflects an assortment of assault, robbery, narcotics, and firearms violations," the CIA Inspector General wrote, and included a 1971 drug conviction and a 1977 arrest for conspiracy to sell marijuana. Former CIA official Alan Fiers admits being aware of Vidal's "record of misbehavior and general thuggery" but claims he didn't know the Cuban was a convicted drug trafficker. The following month, Owen informed North that "the first hard intelligence mission inside by boat has taken place and the people arc now out." He said five small boats were being constructed and "a safe house [in Costa Rica] has been rented on a river, which flows into the ocean."

"Moises Nunez, a Cuban who has a shrimping business in Punteranous [sic] is fronting the operation," Owen wrote North. "He is willing to have an American come work for him under cover to advise the operation. ... If we can get two shrimp boats, Nunez is willing to front a shrimping operation on the Atlantic coast. These boats can be used as motherships. I brought this up awhile ago and you agreed and gave me the name of a DEA person who might help with the boats."

In other words, in early 1986 the DEA was being asked to provide cheap oceangoing vessels to a company started by the Medellin cartel, run by drug traffickers, for espionage missions planned and fronted by drug traffickers.

The identity of Vidal's high-ranking DEA contact was not divulged, nor is it known whether the agency ever provided the boats, but records show the maritime operation was going strong in April 1986 and would soon be running "several trips a week," according to a memo Owen sent to North. Curiously, the Iran-Contra investigations barely looked at this clandestine operation, which was a clear violation of the Boland Amendment since, according to Owen, it directly involved CIA station chief Joe Fernandez.

Despite his background, Moises Nunez also maintained a chummy relationship with antidrug agencies, both American and Costa Rican. "Nunez got to be known by our authorities as a collaborator of the DEA and of other police bodies," said a 1989 Costa Rican prosecutor's report, adding that the Cuban carried credentials from the Costa Rican Ministry of Public Safety's Department of Narcotics, provided funds and vehicles for an antidrug unit, and went out on raids with them, though his effectiveness was somewhat questionable. The report said he blew a four-month investigation of a Colombian drug ring by making a "premature" arrest.

Most of this strange activity was occurring with the knowledge and apparent approval of CIA station chief Fernandez and other CIA agents in Costa Rica, records indicate. Fernandez admitted to the Iran-Contra committees that he knew Nunez and knew he was meeting with Owen to discuss Contra operations. Fernandez was asked if he knew that Nunez claimed to have met North, but his answer was classified for reasons of national security.

Nunez, however, shed light on that question when the CIA interrogated him in March 1987 about allegations that he'd been dealing drugs in Costa Rica through his shrimp company, Frigorificos. Thanks to a DEA seizure, the CIA already knew that Nunez's partners in that firm were behind a 414-pound cocaine load shipped to Miami in January 1986 amidst crates of yucca.

"Nunez revealed that since 1985, he had engaged in a clandestine relationship with the National Security Council [NSC]," the CIA Inspector General reported. "Nunez refused to elaborate on the nature of these actions but indicated it was difficult to answer questions relating to his involvement in narcotics trafficking because of the specific tasks he had performed at the direction of the NSC."

Instead of following up on this eyebrow-raising answer, CIA headquarters ordered an immediate halt to Nunez's questioning. "The Agency position was not to get involved in this matter and to turn it over to others because it had nothing to do with the Agency, but with the National Security Council," former CIA officer Louis Dupart reasoned in an interview with the CIA Inspector General. "That's all we had to do. It was someone else's problem." That "someone" was harried Iran-Contra prosecutor Lawrence Walsh, upon whom every potential allegation of drug trafficking by the Contras was dumped by the CIA and the Reagan Administration. Of course, Walsh had neither the time nor the authority to look into most of those leads and the CIA refused to cooperate on the few occasions when he did ask some questions. Therefore he made an excellent scapegoat in case anyone wondered why tips about drug dealing by the NSC and the Contras were never investigated. "We turned it over to Lawrence Walsh," became the Agency's standard reply.

Former CIA official Alan Fiers, who ran the Contra project at the time, confirmed that Nunez's questioning was stopped "because of the NSC connection and the possibility that this could be somehow connected to [North's] Private Benefactor program, otherwise known as the Iran-Contra affair."

The CIA made the same decision when a security check on the CIA's logistics advisor to the Costa Rican Contras, Cuban mercenary Felipe Vidal, discovered evidence of drug running.

"Narcotics trafficking relative to Contra-related activities is exactly the sort of thing that the U.S. Attorney's Office will be investigating," CIA attorney Gary Chase worried in an August 1987 memo. Chase "expressed concern over the possibility that the security process. . .could be exposed during any future litigation." Vidal's security check was shut down.

But the Agency's conduct was far worse than simply burying its head in the sand. For years afterward, it shielded both Dago Nunez and Felipe Vidal from criminal investigations into drug trafficking and money laundering. At various times, the CIA told U.S. Customs and the DEA that it had no information about Nunez's trafficking activities. The CIA's Directorate of Operations—which runs covert operations—lied even to the Agency's own lawyers, denying knowledge of Nunez's shrimp company though there was plenty of information in its files.

Fiers also confirmed that the CIA played a critical role in the "humanitarian" aid operation involving Frigorificos; without the agency, Fiers said, the NHAO was simply "a shell entity. . .. We were to be the eyes and ears of the NHAO office. The only way that they could monitor alignments, verify shipments and receipts was by having CIA capabilities in the region perform that function for them. And so that's what we did." But since at least three other drug-dealing companies ended up working for the NHAO during its brief lifespan, either the CIA's oversight was woefully incompetent or it was seeking a special kind of contractor.

One such company was DIACSA, the Miami aircraft company that Floyd Carlton had used for years as the U.S. headquarters for his Panamanian drug¬ smuggling venture with Noriega. It was in DIACSA's offices, Carlton admitted, that he and his partners plotted their drug flights and arranged the laundering of their cocaine profits. DEA records confirm that.

Just like Frigorificos, DIACSA was run by a Cuban drug dealer who had been part of the CIA's Bay of Pigs operation, Alfredo Caballero. Carlton testified that Cabellero was "involved with drug trafficking and to a certain extent he helped the Contras. But to be more specific he was helpful to Mr. Pastora's organization [ARDE]."

According to a Senate subcommittee report, the Contras were dealing with DIACSA even before it was hired by the State Department. "During 1984 and 1985, the principal Contra organization, the FDN, chose DIACSA for 'infra¬ account transfers.' The laundering of the money through DIACSA concealed the fact that some funds of the Contras were deposits arranged by Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North," the report stated.