A Pin For St. JudgeIN A MODEST working-class neighborhood of Yonkers, Nev. York, Bill McInenly dutifully retrieved from the basement a mahogany box containing what little was left from his Uncle Hughie's life. He placed the small treasure chest squarely on the dining room table and reverently lifted back the lid. Inside, neatly arrayed in a wooden drawer resting on slats, were all the objects Ruth Redmond could salvage of her son's life. A medal from the Boy Scouts. Honors for winning the broad jump and high jump at Roosevelt High. A silver cigarette lighter with the initials "HR" for "Hugh Redmond." He so loved his smokes.

Here was his weathered Selective Service card. It showed he did not wait for the outbreak of war to be summoned to service, but enlisted on July 1, I 941. He had blue eyes, it said, blond hair, and a fair complexion. He stood but five feet four inches and weighed 155 pounds Actually his eyes were a pale and gentle blue, his hair thick and wavy, his complexion white as flour. And there was nothing diminutive about him. His frame was broad and taut.

Beside the Selective Service card was a small box holding a collection of military patches, among them the Screaming Eagle from the 101 st Airborne. There were also a lieutenant's bars and a sharpshooter's medal.

From the contents of the box it might appear Redmond was among the lucky ones. On June 6, 1944 -- D-Day -- he landed near the Douve River in Normandy. Of the twenty paratroopers in his group, he alone was neither wounded nor killed. Here, in an old box of matches, was a twisted and dark fragment of metal. With it was a note held by yellowing tape. It reads, "Shrapnel dug out of hip in hospital in Brussels, 1944." This was a personal souvenir of his fight in the Market-Garden campaign in Holland. The date was September 22, 1944. Again he had been lucky.

But Redmond's luck faltered at the Battle of the Bulge. His wounds required a year in a hospital bed. Set into a blue leather box was his Purple Heart "for Military Merit." A Silver Star. A Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Clusters. Beside it was a certificate of discharge from the military dated October 18, 1945. After that, judging from the contents of this drawer, he simply ceased to exist.

Mixed in with the possessions of Hugh Francis Redmond were a few things of his mother's, Ruth's. A small religious pin of St. Jude, her patron saint. On the back is inscribed "Apostle of Hopeless Cases." No other saint could have understood so well Ruth Redmond's prayers of vigil.

Beneath the drawer was a chest full of old newspapers, a passport, a birthday card to Hugh that was returned. Here and there was a scattering of old Chinese coins.

A box of clues. A life reduced to mystery

Moments later Bill McInenly went back to the basement and returned with a second, less decorous box. This one was more of a rubber tub, blue and covered with a snap-on lid. It was the kind of container in which one might find beers on ice at a tailgate party. But inside, carefully folded to a perfect triangle, was a musty American flag.

***

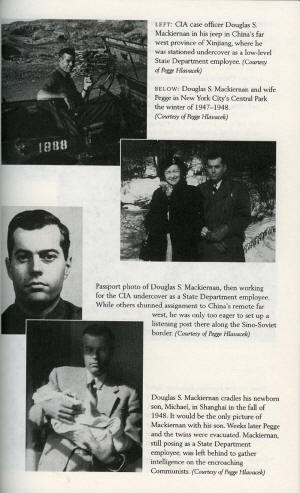

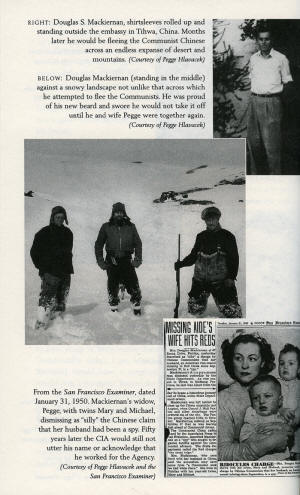

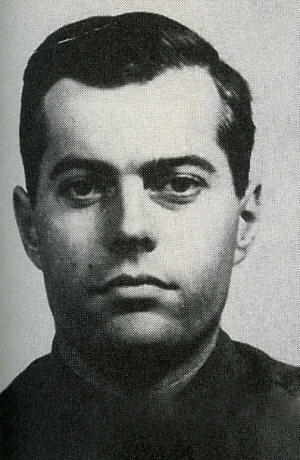

Any telling of Hugh Francis Redmond's life must begin where the contents of his nephew's box ends. It is Shanghai, China, on April 26, 1951 -- just three days shy of a year after Douglas Mackiernan was gunned down on the Tibetan border. Thirty-two-year-old Hugh Redmond was now living the good life overseas. But that good life appeared threatened as the Communists tightened their stranglehold on activities in Shanghai All foreigners were under suspicion.

A short time earlier, Redmond had secretly married. His bride was named Lydia, though he affectionately called her Lily. She was a White Russian and a piano teacher, a dark-haired and shapely woman who some would say was a femme fatale. With Redmond's help she had managed to leave China. Now it was his turn. He prepared to board a ship, the USS Gordon. But Redmond's voyage was abruptly ended even before it began.

Police from China's dreaded Public Security Bureau boarded the ship, escorted Redmond off, and led him away without explanation. Almost immediately rumors began to circulate around Shanghai and Washington that he had been executed.

The Chinese Communist regime under Mao Zedong had rounded up many foreigners, even missionaries attempting to spread the gospel. But Redmond was a case apart. As a commercial representative of Henningsen and Company, a British concern that specialized in the import and export of foods, Redmond appeared to be little more than a salesman -- hardly a threat to Mao's regime. Never one to raise his voice, Redmond seemed so ordinary a fellow that even at the smallest of gatherings he was all but invisible. It was no wonder, then, that when the police pinched him off the ship, he literally vanished.

His parents had grown accustomed to long periods without a letter from him. But even they, in time, began to worry when they didn't hear from him, especially his mother She was a cafeteria worker in a Yonkers public school. But it was not his personal life or business that kept her awake at nights. No, there were things that she knew about him, things that she had sworn not to discuss with anyone, that gave her ample cause for concern. His very life might depend on her discretion.

Ruth Redmond knew only that her son had joined a shadowy element of the War Department called the Strategic Services Unit, or SSU, and had gone to China on some sort of secret mission. In late August Hugh Redmond had arrived in Shanghai. His work as an import-export trader with Henningsen and Company was merely a cover, providing him the perfect pretext for travel and contact with the Chinese.

Even in the midst of China's tumultuous revolution, he appeared to prosper. On August 22, 1946, he wrote his parents. "I am living in the French section of Shanghai on the Rue De Ratard -- a very nice section of town. The house has large grounds and gardens, two tennis courts, a big patio, a bar in the dining room and plenty of recreational equipment -- pool tables, etc. Countless Chinese servants are running around to do anything you want." Unfortunately, wrote Redmond, he would soon have to vacate these opulent surroundings.

"Nothing much to say, everything quiet here except the Communists," he wrote. In a postscript he added, "May not write for quite a while."

"A while" stretched on month after month. A worried Ruth Redmond wrote the State Department in September 1949 -- long before her son's arrest -- to see if the government could provide any clue as to his whereabouts. A State Department employee, unaware of Redmond's covert status, cabled Hong Kong and made inquiries of him with his employer, Henningsen and Company. A spokesman for the firm said they had no record of a Hugh Redmond working for them. The State Department concluded Ruth Redmond was confused.

But the response alarmed Ruth Redmond even more. She saw it for what it was, a slipup in the cover story. At her request the State Department made a second inquiry with the British consulate in Shanghai. They confirmed that Redmond did indeed work for Henningsen and that he was just fine. For the moment her concerns were eased.

But her underlying fears persisted. For two years the United States had been urging its citizens to leave mainland China. It could no longer offer them protection or assistance. Red China, as it was known, was not recognized by the United States. There was neither an American embassy in China nor any official U.S. presence there. Anyone who stayed did so at his or her own peril.

Like Mackiernan, Redmond understood that each day he stayed in China the risk increased. Finally his superiors decided it was time to pull the plug on his operation. An encrypted message was sent to his apartment. It read simply, "Enjoy the dance." But Redmond delayed his departure a brief time longer, tidying up his affairs there.

At the time of Redmond's arrest in the spring of 1951, there were an estimated 415 Americans still in mainland China. On Apri130, 1951, four days after Redmond's arrest, the State Department compiled a secret list of Americans believed to be imprisoned in China. There were then thought to be twenty-three, eighteen of whom were missionaries. Beside Redmond's name was this notation: "may be executed." Four months later an embassy memo from Hong Kong to Secretary of State Acheson reported that "it was common belief among Chi [Chinese] and foreigners that Commies had proof against him and had executed him for espionage." The rumors were credible enough. Virtually any American still in China was suspected of spying.

There was no way of knowing if Redmond was still alive. Americans in Chinese prisons were held incommunicado. They had no right to a lawyer. Some were tortured. Few had been formally charged, though many had been accused of a wide range of offenses -- plotting against the government, spreading rumors, illegal possession of radios, currency violations, fomenting disorder, and even murdering Chinese orphans.

The U.S. government kept silent on Redmond's fate, as it did with nearly all those believed to be imprisoned in China. Taking the issue public might make the Chinese even more resistant to the idea of eventually releasing them. It might also endanger their lives. Behind the scenes, the State Department persuaded Britain and eight other nations to inquire about the well-being of Redmond and other prisoners and to work for their release.

On October 19, 1951, the secret list of Americans held by the Chinese -- which included Redmond's name -- was provided by Assistant Secretary of State Dean Rusk to U.S. Senator William Knowland at the senator's request. Knowland had pledged that the list would remain confidential. But on December 8 Knowland released the names to the press and issued a blistering denunciation of the Chinese. The next day Redmond's name surfaced publicly for the first time in front pages around the nation.

And that was how Ruth Redmond first discovered that her son had been imprisoned, or even executed. Given what she knew of her son's covert employment with the government, she was horrified that no one from the intelligence service had informed her of her son's situation. She might have been even more disturbed if she had known that by then her son had been largely forgotten by those in the recently reorganized clandestine service.

On December 18, 1951, she penned a letter addressed simply "State Department, Washington D.C." It read: "Dear Sirs, I have a son in China for the last few years. I naturally have been worried about him continually but was shocked beyond words to read in the newspapers that he has been in prison in Shanghai since April 26, 1951. This is the first news of any kind I have had of him. For obvious reasons he was listed as a businessman. After three years on the battlefield in Europe and now this -- is there any hope for my only son? Is it possible to find out if he is well, if he is hungry, if he is mistreated. Can we write to him, can he receive any packages from us and is anything being done to secure his release? Thank you for any information you may have. I am sincerely, Mrs. Ruth Redmond. My son's name, Hugh Francis Redmond."

***

There can be little doubt that Hugh Redmond understood the risks of his assignment. On July 24, 1946, just nine months after he had left the army, he joined a top secret intelligence organization within the War Department. Like many highly decorated veterans of World War II, he was eager to continue his service to country, but he had suffered grave wounds in the war. It was doubtful that he would have been eligible for active military duty. And so, like many other casualties of war, he sought out the next closest thing -- the clandestine service. In those early days the corridors of the clandestine service had more than their share of men with limps, eye patches, and other tokens of war.

Redmond had joined the Strategic Services Unit, the SSU. After President Truman ordered the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to be dismembered as of October 1, 1945, critical elements of that organization, particularly the Secret Intelligence and Counter-Espionage branches, were assigned to the SSU. The unit was initially under Colonel John Magruder, who had been Wild Bill Donovan's deputy director of intelligence at the OSS. SSU's role was to maintain networks of foreign agents, safe houses, and other vital elements of the intelligence apparatus in both Europe and the Far East. What remained from the glory years of the OSS was little more than a skeletal secret service. SSU would later be folded into the Central Intelligence Group, or CIG (created on January 22, 1946), and would finally become part of the Central Intelligence Agency when it was created in 1947.

With each change in name and function, the intelligence corps and its mission became more muddied, the bureaucracy more mired in paperwork and interservice rivalries. By the time of Redmond's arrest in April 1951, it had undergone so many transformations that Hugh Francis Redmond had been all but forgotten. His supervisors had been shuffled about from place to place, and Redmond, already out of country for four years, was at best a vague memory, a series of dusty file jackets in the bowels of a confused bureaucracy.

From the start his mission had been high-risk. Some might say fool-hardy.

In January 1951, four months before Redmond was seized, the CIA drafted a secret memo for the National Security Council and the President. It laid out what it knew of Mao Zedong's China and the prospects for dislodging him. Titled "Position of the United States with Respect to Communist China," it was a sober read. "For the foreseeable future," the memo began, "the Chinese Communist regime will retain exclusive governmental control of mainland China. No basis for a successful counter-revolution is apparent. The disaffected elements within the country are weak, divided, leaderless and devoid of any constructive political program."

The only opposition remaining, the Agency concluded, was bandits, some minor peasant uprisings, and "actual guerrilla forces, made up of Nationalist remnants, Communist deserters, adventurers, and a few ideological opponents of the regime." It was a dire take on events in China. The best that CIA clandestine operatives could hope for would be to create diversions that, for the time being, might distract if not contain the Chinese military. Seen in that light, Hugh Redmond was a double casualty. He had been sent into an impossible situation and then had fallen through the bureaucratic cracks.

While Doug Mackiernan had been gathering intelligence on the far western front of China, Redmond had been busy in the east, operating out of that country's major economic center, Shanghai. Mackiernan and Redmond were both early versions of CIA case officers. Their job, in the lingo of the Agency, could be reduced to three simple terms: spotting, recruiting, and running agents. Contrary to popular literature and film, "agents" were not employees of the Agency but foreign nationals with access to information, documents, or materiel that could be of national security interest to the United States.

Most case officers were like Mackiernan. They operated under "official cover," meaning that to the rest of the world they worked for the U.S. government but in a consular or embassy position. They often melted into the ranks of lower-level diplomats. But Redmond, posing as a businessman, enjoyed no such official cover. He was, in the jargon of espionage, a NOC, an acronym for "nonofficial cover." Such cover is deemed deeper and more difficult to penetrate, but also affords less protection if the person's cover is compromised. Without the guise of diplomatic cover, a covert operative is more vulnerable to arrest and incarceration for espionage. All the more so in the case of Hugh Redmond, who did not limit himself to gathering intelligence, but actively supported those engaged in resistance efforts and sabotage.

For the CIA, still in its infancy, the disappearance of Hugh Redmond, while disturbing, was hardly of major import. The Cold War had turned decidedly hot with the advent of the Korean conflict. The Agency's inability to predict that monumental event, following so close on the heels of its failure to forewarn of a Soviet A-bomb, further eroded confidence in its skills

Even the Agency's director, General Walter Bedell Smith, conceded that the CIA was not yet up to the tasks that faced it. Once-secret minutes from an October 27, 1952, meeting note: "The Director, mentioning that the Agency had recently experienced some difficulties in various parts of the world, remarked that these difficulties stemmed, by and large, from the use of improperly trained or inferior personnel. He stated that until CIA could build a reserve of well-trained people, it would have to hold its activities to the limited number of operations that it could do well rather than to attempt to cover a broad field with poor performance." Bolstering the ranks with highly trained officers was to be a top priority in the years ahead.

Adding to that pressure was the very real threat of atomic espionage and the witch-hunts of Senator Joseph McCarthy from which not even the Agency itself was exempt. On November 1, 1952, the United States detonated the first hydrogen bomb, over the Marshall Islands, all but vaporizing the island. It was a none-too-subtle warning to Moscow and Beijing that the United States was not to be taken lightly.

But anti-Communist hysteria was rampant. Senator McCarthy held the government hostage with his bogus list of Communist infiltrators and his choreographed hearings. The very culture of the country seemed obsessed with "the Red Scare." In 1952 the film High Noon was released. Billed as a cowboy movie, it was a thinly veiled allegory of the plight of liberals and leftists nationwide and of the impact of fear and suspicion on a community.

The next year the Rosenbergs, Julius and Ethel, were electrocuted for selling atomic secrets to the Soviets. That same year Casino Royale, by British author Ian Fleming, was published. It introduced readers to suave and swashbuckling James Bond, Agent 007, who liked his martinis "stirred not shaken." Redmond and Mackiernan, trained in maintaining invisibility, would have scoffed at such high-profile antics.

Throughout these early years the CIA was busy trying to keep up with an ever-expanding mandate. Resigned to the fact that it had little chance of actually toppling the Soviet Union or China, it contented itself with sponsoring behind-the-lines acts of sabotage designed to divert and frustrate the two Communist giants who were seen as bent on expansionism. It also resolved that it would blunt any attempt to spread Marxism beyond the Communist states' existing borders. That meant turning its attention and resources to those regimes and proxy status that tilted even remotely to the left.

But the Agency's successes would have been of little consolation to Ruth Redmond. On May 20, 1952, more than a year after her son's disappearance, she wrote U.S. Senator Herbert Lehman, "My son is one of the Americans held in prison for more than a year and so far nothing has been done to secure his release -- one cannot help but ask why a country like ours for which he fought in World War Two can be so lax in behalf of her people. My one ambition is to again see my only son and beseech you to add your efforts in his and the other Americans behalf by appealing to the Dept. of State to take effective action."

Month after month Redmond's name appeared on the State Department's internal list of Chinese prisoners, always accompanied by the notation "may be executed." Even if somehow Redmond was alive, his condition was likely to be grim. In July 1952 the State Department interviewed an American attorney named Robert Bryan, who had been in Shanghai's notorious Ward Road jail -- here Redmond, too, would have been held, if he was still alive. Bryan had been living in Shanghai for years and had been arrested just two months before Redmond. He was placed in "the death cell," given a leaky bucket as a latrine, and branded an "American imperialist pig" by his captors. His treatment gave the State Department a picture of what Redmond, too, might be going through.

"Your hands are stained with the blood of our comrades," the Chinese had shouted at Bryan. He was subjected to an endless barrage of indoctrination and interrogation. He was beaten with a rubber hose. He was held in solitary confinement and lost forty-six pounds. Twice, he said, he was given a spinal injection of some kind of truth serum. Finally he signed a series of confessions and on June 26 was released and placed on a train to Hong Kong and freedom.

That summer, eighteen other Americans in prison or under house arrest were also set free. In the months after, more were released, many of them missionaries who had been tortured. But those stories were largely stifled at the State Department's request. Reports of brutality, they feared, could inflame the Chinese and endanger those Americans still captive.

But Redmond's arrest had no effect on the CIA's pursuing its high-risk operations against China. Notwithstanding its own findings that the Communist regime was firmly in command and control of the country, it continued to support and equip cells of resistance on the mainland, taking enormous risks in the process. One of those gambles went badly awry.

On November 29, 1952, an unmarked C-47 Dakota based in Japan and equipped with flame suppressors to render it less visible at night was flying over Manchuria on a top secret mission. On board were two American pilots, seven Taiwanese agents set to infiltrate the mainland and set up a communications post, and two covert CIA officers overseeing the operation. One of these Agency officers was twenty-five-year-old John T. Downey, nephew of the singer Morton Downey. A classic Agency blue blood, he was the son of a Connecticut judge. He had attended Choate, where he was voted "most likely to succeed," and Yale, where he was captain of the wrestling team. Downey had been one of thirty Yale students the spring of his senior year who had been drawn to a CIA recruitment notice posted on the New Haven campus. He and the others were wooed by an Agency recruiter, a tweedy veteran of the OSS who smoked a pipe and wore a Yale tie. Immediately after graduating in June 1951, Downey enlisted. Back then, the Agency was so young that most of these natty recruits had never even heard of the CIA.

The other Agency man aboard the C-47 that night was twenty-two-year-old Richard G. Fecteau. He was a shy and withdrawn man, a twin and father of twin three-year-old daughters.

At a preset rendezvous point the plane, part of the CIA proprietary airline Civil Air Transport, was to descend and scoop up an agent in a sling, then go on to drop a team of Chinese Nationalist paratroopers into the Manchurian foothills. As the plane came in on its approach, it came under small-arms fire and crashed. The two pilots, Robert Snoddy and Norman Schwartz, died in the crash and were buried on the spot. Their graves were never found. The paratroopers were executed by the Chinese. As for CIA officers Downey and Fecteau, nothing more was heard from them. Like Redmond, they had vanished.

The United States, clinging to the Agency's cover story, said Downey and Fecteau had been employees of the Defense Department on a routine flight between Seoul and Tokyo. Out of public view the CIA silently mourned the loss of Downey and Fecteau, as did the mothers and widows they left behind.

By then, more than a year had passed since Redmond's disappearance. The presumption was that he, too, was dead.

Then, on March 29, 1953, a former German citizen who had been held in a Shanghai jail since March 1951 was released and arrived in Hong Kong. With him he brought the first word of Hugh Redmond. Between March and October 1951 the German had occupied a cell next to Redmond in the Lokawei military barracks. At the time, he reported, Redmond appeared to be receiving relatively "soft treatment" in an effort to get him to confess to espionage. Then later, between March 17 and 24, 1952, at the Ward Road prison he could hear Redmond being interrogated on the floor below.

Others released from Chinese prisons later told U.S. authorities that while they had not seen or heard anything of Redmond, those who had associated with him prior to his arrest were being rounded up and charged with espionage.

By the fall of 1953 the State Department had begun to worry even more about the well-being of Redmond and the other twenty-eight Americans still held by the Chinese. Another winter was approaching. At least five Americans had already perished in Chinese prisons, presumably from maltreatment.

***

In November 1953, a year after the downing of the plane carrying Agency officers John Downey and Richard Fecteau, the CIA assembled a panel of experts in a conference room in the Curie Building, one of the temporary structures beside the Potomac. They gathered to weigh all available intelligence and decide whether it was reasonable to conclude that Downey and Fecteau were dead. Present that day was a representative from the general counsel's office, an Agency physician, all other from operations in the Far East Division, and someone knowledgeable about the terrain and conditions of the crash site. Also present was Ben DeFelice, soon to be named chief of the Casualty Affairs Branch.

Then, and in the decades ahead, it was DeFelice who was the liaison between the Agency and the families of those CIA employees who were imprisoned, killed in the performance of duty, or missing in action. It was a difficult job, balancing the need for continued security and secrecy with the demands of compassion and patience. DeFelice would repeatedly do battle with the bureaucracy on behalf of those who had suffered a loss. His gentle hand would assuage the grief of generations of widows and children orphaned by the not-so-cold Cold War, even as he reminded the families of the need to maintain silence.

It was DeFelice who inherited the Redmond, Downey, and Fecteau cases and who redefined how the Agency would help stricken families while shielding the Agency from unwanted exposure. He would quietly remind them that if the press should make inquiries, nothing need be said.

DeFelice would draft letters of condolence to the widows or widowers of those who suffered losses. Those letters would find their way to the desk of the Director Central Intelligence and go out under the director's name. So it was with Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, George Bush, and the other Directors Central Intelligence.

Such letters would typically be hand-delivered to the widow just after the funeral. The widow would be permitted to read the letter and then, in the interest of national security, she would be asked to return it to the Agency officer who was present. The letter would then be placed in the deceased's personnel file and the widow or widower would be left without any potentially embarrassing evidence to link the decedent to the CIA. As DeFelice would tell the grieving widow, he didn't want to burden her unnecessarily. Medals, too, would often be presented and then immediately withdrawn and secured in the personnel file at headquarters.

In November 1953 DeFelice and other Agency officers gathered for the sober purpose of reviewing the Downey and Fecteau files. After a person had been missing for a year, the Agency was empowered, under the Missing Persons Act, to deliberate whether it was reasonable to conclude that he or she was dead. After a year there had been not even a hint that the two CIA airmen had survived the shoot-down of their aircraft over Manchuria. The terrain of the crash site was rough and it was known to be rife with wolves. Had they been lucky enough to outlive the crash and avoid the hail of gunfire, then the wolves would surely have devoured them.

That was the official conclusion reached by DeFelice and the other CIA panelists that day as they issued a formal "Presumptive Finding of Death." With that finding in hand, DeFelice could start the process of releasing workers' compensation benefits to the families of the two men, as well as insurance proceeds. The case was closed, a copy of the finding was placed in the men's personnel folders, and benefits were settled. The Agency explained to the Fecteau and Downey families that no mention was ever to be made of their loved ones' connection to the Agency. Both families honored that request.

***

Meanwhile the fate of Hugh Redmond remained clouded. It would be some time before anyone at the CIA would take a personal interest or even be made aware of Redmond's fate. That person was Harlan Westrell. He had joined the Agency in 1948. By the mid-1950s he was chief of counterintelligence in the Agency's Office of Security. His office was in the decrepit Tempo I building. When it rained, the roof leaked. On sweltering days, and there were many, he had to peel off the classified papers that stuck to his forearms.

By all rights, the Redmond case should never have found its way to Westrell's desk. It had little if anything to do with counterintelligence. Westrell's job, among others, was to ferret out so-called penetrations, to look for moles and evidence that the Agency's security had been breached. It was not an easy job. He was often butting heads with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who refused to cooperate with Agency investigations. Hoover was still steamed that the FBI had been forced to relinquish to the CIA its intelligence jurisdiction over Central and South America. Westrell was also preoccupied with fending off Joe McCarthy's accusations that the Communists had plants throughout the CIA.

Sometimes Westrell's responsibilities bordered on the absurd. In one instance, he was called upon to dispatch one of his staffers to head up a CIA team consisting of a chemist knowledgeable about poisons, a physician, and an operative. The team leader was James W. McCord, later one of the Watergate burglars. Their mission was to investigate whether someone was slowly poisoning the U.S. ambassador to Italy, Clare Boothe Luce. The team concluded that Luce was not the target of any plot, but that over time, flakes of paint containing lead had fallen into her nightly glass of wine.

Westrell was also responsible for protecting case officers under deep cover from being exposed. The name of each such operative was written on a three-by-five index card -- just the name, nothing else. If someone inside or outside the Agency made an unauthorized inquiry about one of those individuals, Westrell's staff would investigate. His entire office was inside a vault. The cards containing the names of scores of deep-cover operatives like Redmond were locked in a safe within the vault each night.

Precisely how and when Redmond's name and fate came to Westrell's attention is not clear. An Agency unit called the Contact Division, which interviewed travelers returning from trips overseas, had learned from the International Rescue Committee that a recent emigre named Lydia Redmond, an attractive woman of Russian descent, was claiming that she was married to an American government employee who had been arrested in China. At the time, Lydia Redmond was living in Milwaukee.

The report piqued concern for Hugh Redmond's well-being; but also raised questions about his judgment. He had not mentioned to either his family or Agency superiors that he had gotten married. Simply fraternizing with a foreign national -- especially one of Russian descent -- would have raised eyebrows. A marriage would not only have been subjected to close scrutiny but might even have been seen as a career-ending error in judgment.

Word of Lydia Redmond filtered down to security chief Sheffield Edwards, who asked Westrell to investigate Lydia Redmonds claim. Westrell assigned it to the CIA's Chicago field office. A preliminary inquiry suggested that she was telling the truth, though the Redmond family knew nothing of the marriage and there was nothing in the old SSU files to support the claim. But then, the files were woefully incomplete.

Westrell arranged for Lydia Redmond to move to the Washington area. He helped her get a job with the Veterans Administration and an apartment in Arlington, Virginia. At their first meeting the two dined at (appropriately enough) a Chinese restaurant, the Moon Palace, on Washington's Wisconsin Avenue. The restaurant was new and they were its first customers. Lydia spoke Chinese to the waiter.

The deeper Westrell looked into the Redmond case, the more he was convinced that in the confusion that followed the transfer of SSU's functions to CIG and then to CIA, Redmond had fallen through the cracks.

He decided to go to Yonkers to meet Redmond's mother, Ruth. She had not heard anything from her son in more than two years. In Yonkers Westrell later selected a local lawyer, Sol Friedman, to be the Agency's "front man" representing Mrs. Redmond's interests and keeping the Agency informed of her situation.

***

What little was known of Hugh Redmond's situation came from interviews with those few Americans and foreign nationals who were released from Chinese prisons and later debriefed after entering Hong Kong. The one observation shared by all was that Redmond had remained steadfastly defiant of his Chinese captors.

It was ironic that, even as Redmond stood his ground, refusing to confess to espionage or to bend to relentless efforts at indoctrination, his own agency, the CIA, had become fascinated with the idea of mind control. Many were convinced that the Chinese possessed the ability to "brainwash" a man, to break his resistance and render him a willing pawn. During the Korean War the Agency watched in horror as some American servicemen held by their captors mouthed Communist propaganda. A few even opted to defect. In an effort to understand that power -- and to acquire it for themselves -- the CIA, under its esteemed director, Allen Dulles, began a massive research program into mind control in I953. The idea was partly that of Richard Helms, himself destined to become one of the most powerful and controversial of CIA directors. Code-named MKULTRA, the program involved the testing of LSD and other psychoactive drugs.

On November 18, 1953, one such experiment went terribly awry as an army civilian researcher named Dr. Frank Olson was unwittingly administered a dose of LSD. In the days following, Olson became depressed and underwent changes in his personality. The CIA, alarmed at his behavior, sent him to New York for psychiatric treatment. Eight days after the LSD was administered, Olson hurled himself through the window of his tenth-floor room at the Statler Hotel, plunging to his death.

After Olson's death, the cause of which was concealed from the public for two decades, the CIA decided it was imperative to have someone from its Office of Security present each time someone was administered LSD or other psychoactive drugs. It was Harlan Westrell and his office that were called upon to provide such protective services. The MKULTRA program continued unabated until 1961. During that time the American public knew nothing of the Agency's mind-altering experiments.

When a more detailed account of Redmond's condition finally surfaced, the news was not good. On April 23, 1954, the American consulate in Hong Kong sent a cable to Secretary of State Dulles reporting on its interview with a French Catholic priest who had just been released from a Chinese prison. The priest said he had secret conversations with Redmond and shared a cell with him from September 16, 1953, until April 19, 1954. Redmond was being held in Shanghai's Rue Massenet jail under tight surveillance.

The cable noted: "He is in a cell with Chinese prisoners, forbidden talk with them and given minimum exercise, low grade food, minimum medical care to sustain life. His spirits are quite good, he resists minor tyrannies of guards and interrogators, and steadfastly refuses confess accusations of espionage and possession of arms." But the prolonged incarceration was taking its toll. His health was deteriorating. For violating minor prison rules, his hands and feet were manacled. He had been interrogated relentlessly.

On June 21, 1954, the news was conveyed to Redmond's mother. She sent the State Department a note of thanks and asked if she might send food or clothing to her son or to write to him. "We have waited so long for news, she wrote.

On June 4, 1954, another Catholic priest, Father Alberto Palacios, was released from Shanghai's Lokawei jail, a special military facility reserved for political prisoners. On August 6 the consulate in Hong Kong sent a cable to Washington summarizing what Palacios had told them. Copies of the dispatch went to the CIA. Palacios reported that Redmond was completely without private funds and that he was wearing shoes provided him by prison authorities. His clothes were now little more than rags. He was no longer being interrogated, and though he was in good spirits his health was failing. He now had beriberi, near-constant diarrhea, and an inflammation of the corneas of his eyes. The prison guards were treating him with vitamins.

Redmond's prison routine was unvarying. He and the other prisoners were awakened at 5:30 A.M. and given half an hour to wash and relieve themselves. They were allowed forty-five minutes to sit on a cold wooden floor to meditate or read. Breakfast was liquid rice gruel and occasionally turnips. There was then an hour to clean the room and go to the toilet. Lunch was served at noon and consisted of dry rice and vegetables, supplemented with meat once a month. Three times a day, for fifteen minutes each, Redmond was allowed to walk around the nine-by-eighteen-foot cell. Dinner was rice and vegetables. Most days were to be spent in meditation or reading Communist literature, both of which Redmond steadfastly refused. There were times when he was forced to stand in a corner for up to forty-eight hours.

But after four years, Chinese prison officials had still made no progress in persuading him to confess or to embrace Communism. Instead, Redmond was increasingly hostile. When the ventilator fan was loud enough to obscure his voice, he would sing lustily. He had hectored the guards into granting him certain small privileges denied to others, including being able to go to the bathroom unaccompanied. Though the prison did not allow smoking, he had cajoled his interrogators into granting him a cigarette before he would even acknowledge their presence. And when two female interrogators attempted to interview him in Russian, he refused to speak the language, forcing them to revert to English. Slowly but surely, it was the guards who seemed to be wearing down and Redmond who appeared to be gaining control over his captors.

Conversation with Redmond had been difficult. He and Father Palacios had to wait until another inmate, a Communist informant, was out of the cell. "I was put in for spying," Redmond confided to the priest. Redmond told him that no decision had yet been made in the case against him. He spoke briefly of his wife, now in the States. In the three years of his incarceration Redmond had acquired a commanding fluency in both Chinese and Russian. Each day he read Shakespeare and studied Russian grammar. The lad from Yonkers who had dropped out of Manhattan College after only a semester was becoming a scholar.

In June 1954 the Chinese sent a signal that perhaps they were softening their position on Americans held there. At meetings in Geneva, Switzerland, the Chinese delegation announced that it would allow packages and mail to be sent through the Red Cross Society of China to American prisoners. The State Department notified Ruth Redmond, who immediately sent several letters and packages to her son.

For the first time in years, Ruth Redmond felt a buoyancy, an unspoken hope that Hugh might soon be released and his suffering brought to an end. Then came crushing news.

On September 12, 1954, the Chinese government, through its state-controlled New China News Agency, announced that Redmond had been tried and convicted of spying. The sentence was life imprisonment. Redmond was one of eight people that day convicted by the Judge Advocate General's Department of the Shanghai Military Control Committee. The regime boasted that it had smashed a major espionage ring operating out of Shanghai. It detailed Redmond's activities, from the time he was dispatched to China in August 1946 to his alleged spying in Mukden, Beijing, and Shanghai. The Chinese court said he had been part of a covert unit called the External Survey Detachment 44.

The other seven, five men and two women, were Chinese. Two of them, Wang Ko-yi and Lo Shih-hsiang, were sentenced to death and executed immediately -- in front of Redmond. Wang, the Chinese said, had worked with the OSS. Under Redmond's direction, it said he had set up radio transmitters, expanded the spy ring, and collected sensitive military and political secrets that were sent to U.S. intelligence officers in Hong Kong. They were also said to be preparing a campaign of sabotage.

The Chinese Public Security Bureau claimed that, in rounding up the spies, it had found a cache of sophisticated espionage equipment -- five radio receiving and transmitting sets, sixteen secret codebooks, six bottles of chemical developer for invisible messages, a case of machine-gun bullets, a suitcase with hidden compartments, and hundreds of pages of instructions and credentials. At the center of it all was Hugh Francis Redmond. The State Department forwarded a copy of the Chinese press release to the CIA.

In response to the espionage conviction, the State Department issued a vigorous protest. It declared that Redmond was nothing more than an American businessman who had been falsely accused. Ruth Redmond, too, though knowing full well that the charges against her son were true, publicly proclaimed her son's innocence. The image of a poor working-class mother stricken with fear and anxiety over her son moved the entire community of Yonkers and much of the region around it to rally in support of Redmond's release. In the anti-Communist hysteria of the day, the Redmond case became an emotionally explosive piece of evidence that the Reds were utterly heartless and duplicitous.

The day after Redmond's conviction, the news was stripped across the top of Yonkers's Herald Statesman: "Chinese Reds Jail Yonkers Man for Life." The State Department was quoted as saying that espionage was a "favorite trumped up charge of the Communists." The day's lead editorial was headlined "Yonkers Neighbor Tastes Red Barbarism." The editorial spoke of Redmond's heroic service in World War II. "We may well pray that such a fighting spirit can weather the filthy Red prison cells, the handcuffs and brain-washing or other barbarism that the Commies invent and use on him. And we can understand -- from our neighbor's plight -- why we must be grimmer and more determined than ever that such proved barbarians have no place in any civilized aggregation like the United Nations, if we can have anything to say about it."

Redmond had inadvertently become a cause celebre, an instrument of U.S. propaganda -- all of it predicated, of course, upon the simple fiction that he was innocent of the charges of espionage. In virtually every home in Yonkers, and far beyond, Redmond's name became synonymous with the evils of Communism.

In Yonkers, resolutions were passed and petitions signed by innumerable civic and governmental groups -- the Westchester County Board of Supervisors, local chapters of the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars, his alma mater, Roosevelt High, and foremost of all, the Yonkers Citizens Committee for the Release of Hugh Francis Redmond. Even New York's state Senate passed a resolution calling upon President Dwight Eisenhower to renew efforts to win Redmond's release. It cited "patently false charges of espionage." It noted that "his continued separation from his family and loved ones constitutes an affront to our sense of honor, decency and human treatment." Yonkers's High School of Commerce, where Ruth Redmond was a cafeteria worker, drafted its own resolution for Eisenhower.

In neighboring Ossining the Knights of Columbus called on "all Americans of all faiths to pray to Almighty God for the deliverance of Hugh Francis Redmond, Jr., and especially that all Catholics offer their Masses, Novenas and Prayers to implore God and His Blessed Mother to encourage and protect him." Yonkers Mayor Kris Kristensen called on Yonkers's 160,000 residents to observe a weekend of prayer in which clergy from all faiths would provide petitions to their worshipers. Every petition contained the same phrase. "false charge of espionage."

A week after Redmond's conviction, the State Department cabled instructions to its representative in Geneva, who was then meeting with a Chinese delegation. The directive was unambiguous: "You should protest charges against and sentence of Hugh F. Redmond as unwarranted and unjust, pointing out Redmond was known as legitimate trader, employed by respectable business firm, and that Chinese Communists have unfortunately been in the habit of regarding all foreigners as spies."

The U.S. delegation was to ask the Chinese to reexamine the Redmond case. Meeting at the plush Beau-Rivage hotel in Geneva, a member of the Chinese delegation told the U.S. representative that all hope was not lost, "that if Redmond's future attitude and conduct were found satisfactory by Chinese authorities his case might then be reconsidered."

It was a none-too-subtle invitation for Redmond to confess. And indeed, as would become increasingly clear, Redmond held the keys to his own release. If he admitted to spying, the chances were excellent that he would be set free, as had others before him. But then, Redmond was nothing like the others.

Why he resisted so fervently is not clear. His spy ring had been exposed, its members executed or imprisoned. There was nothing left to compromise or protect. Even within the CIA some were whispering among themselves, marveling at his resistance, but also secretly hoping that he might confess and bring to an end his suffering and that of his family. It had been four years since his arrest. In time, many at the Agency concluded it was nothing more than Redmond's own foolish sense of honor that blocked his release, and for that they saluted him.

The ordeal of Hugh Redmond in China mirrored that of his mother, Ruth, in Yonkers. On October 8, 1954, three weeks after his life sentence was handed down, Ruth Redmond wrote a plaintive letter to the State Department. "I have had absolutely no word from my son since later 1950," she wrote. "He was in prison almost a year when I accidentally read it in the papers. Then I realized why his mail had stopped. It has been just silence since then. It is the silence and the helplessness I feel that is driving me crazy. Is there nothing our State Department can do to send our only son home where he belongs?"

***

The CIA was soon to get a second jolt from China. In December 1954 the Chinese announced that two other Americans were about to go on trial for spying. Their names were John Downey and Richard Fecteau -- the two CIA men that two years earlier the Agency had quietly declared dead, shot down over China. Downey might well have wished he were dead. For the first ten months of his detainment he was in chains and leg irons and subjected to relentless interrogation.

As the show trial was about to begin, Fecteau was led into the court room past an array of cameras and lights. Downey, whom he had not seen in two years, was already in the dock. For the cameras Downey had been decked out in a brand-new black padded suit, shoes, and what resembled a beanie hat. The court officer ordered Fecteau to stand beside Downey. Fecteau could see that Downey looked discouraged. He whispered in Downey's ear, "Who's your tailor?" and a familiar smile broke across Downey's face, bewildering the Chinese guards. But the outcome of the so- called trial was never in doubt. Downey was sentenced to life. Fecteau, as his subordinate, got twenty years.

The United States reacted with predictable outrage. Henry Cabot Lodge, delegate to the United Nations, noted the incident was yet another reason why this "unspeakable gang from Peiping" did not deserve to be admitted into the ranks of that world body. The New York Times wrote a scathing editorial, and a U.S. senator suggested that the United States blockade the mainland. To listen to the U.S. government, Downey and Fecteau were simply innocents caught up in Beijing's vendetta.

Behind the scenes, and with a nudge from the CIA, the Labor Department agreed to waive recovery of those moneys already paid out to Fecteau's children, though certain lump sum payments were recovered. The CIA reclassified the two men as active. Henceforth they would be listed as on "Special Detail Foreign" at "Official Station Undetermined."

A year later, in 1955, DeFelice became chief of the Casualty Branch and set about to do what he could on behalf of all who were imprisoned, killed, or missing. He found himself haunted by the fate of Downey, Fecteau, and Redmond. One of his first actions as branch chief was to get permission to invest the ongoing salaries of the men, rather than have them accumulate year after year in CIA accounts. Then he worked out a complex formula that took into account the average career promotions of the men's peers at the Agency, and on that basis granted regular promotions to Downey, Fecteau, and Redmond, thereby increasing their salaries and benefits. Their cases were handled no differently than if they were still operational in the field.

DeFelice was in constant contact with the families. For hours on Sunday afternoons he would be on the phone to Downey's mother, Mary, trying to win the confidence of a woman who was profoundly distrustful of the CIA.

DeFelice also established what came to be called the Ad Hoc Committee on Prisoners, which met regularly to discuss what steps might be taken to win the freedom of those being held. It was made up principally of representatives of the operational side of the CIA. But its real purpose, as devised by DeFelice, was to set up an ongoing forum that would ensure that the men were not forgotten. That "ad hoc" group met for more than twenty years with DeFelice as the chairman.

Meanwhile the campaign by Yonkers citizens on behalf of Redmond continued to build, drawing in members of Congress. In the spring of 1955 Ruth Redmond and leaders of the Yonkers Citizens Committee for the Release of Hugh F. Redmond formally asked to see Eisenhower, both to present him with bound volumes of petitions and to call his attention to Redmond's plight. Eisenhower's staff expressed reluctance, fearing that publicity surrounding such a meeting would encourage the families of others to demand a meeting with the president. Redmond's advocates promised the meeting would remain a matter of strict confidence. The State Department drafted a memo encouraging Eisenhower to see Mrs. Redmond. But Eisenhower declined.

On Saturday, April 16, 1955, Ruth Redmond and William Gawchik, head of the citizens' committee, met with State Department officials. Eisenhower's refusal remained a sore point. A State Department memo notes that Gawchik "felt the government had displayed a deplorable indifference to the fate of Mr. Redmond." State Department officials, among them Edwin W. Martin, deputy director for Chinese Affairs, tried to reassure them that Eisenhower was aware of Redmond's situation but that the U.S. government had only limited options. "We might go to war with the Chinese Communists to satisfy national honor and pride but this would by no means assure the return of prisoners, even if we should win the war, since they might be killed in the process," the State Department official told her.

But talks in Geneva that resumed August 1, 1955, began to produce unexpected results. Within nine months, twenty-eight of forty-one Americans in Chinese prisons were released. That left only thirteen. Among these were the three CIA agents -- Downey, Fecteau, and Redmond. There followed agonizing months of silence.

Then, in the fall of 1955, the postman delivered a letter to the Yonkers home of Ruth Redmond. She recognized the handwriting instantly and felt her heart racing. The letter was undated and handwritten in ink on air mail stationery. The envelope had been forwarded by the Chinese Red Cross Society in an envelope postmarked September 14, 1955.

Inside were the first words from her son in the more than five years since he had been arrested. "I am very well," he wrote, "and I hope that everyone at home feels as good as I do right now." But Mrs. Redmond already knew something of her son's failing health and that anything he wrote would have had to clear the prison censor. Even so, there was a suggestion that not all was well with him. "Where I am right now," he penned, "there is a hospital, and I am receiving adequate care." He wrote that he no longer needed medicine for his beriberi or ointment for the inflammation that afflicted his eyes. His only request: heavy woolen clothes. Winter was fast approaching.

The brief letter ended with these words: "I'm sending all my love to you and everybody back home. Keep your fingers crossed for me. Love, Hughie." That he had been allowed at long last to write she took to be evidence that the Chinese were not without feelings. It was, perhaps, the sign she had been praying for that her son's deliverance was not far off. Even those at the CIA who monitored Redmond's case felt a tinge of optimism.

But for the Redmond, Downey, and Fecteau families, a long time -- seemingly an eternity -- would pass before their loved ones' fates would be resolved.

Hugh Redmond and his mother, Ruth, pose for a photo against the wall of a Chinese prison where Redmond was being held. After years of incarceration, the once-athletic Redmond would lose all his teeth and become afflicted with disorders of which he was forbidden to speak, even to his mother. (Courtesy of William McInenly)

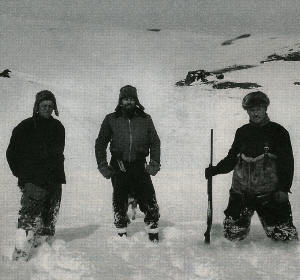

At New York International Airport -- Idlewild -- the mothers of (left to right) Richard Fecteau, Hugh Redmond, and John Downey (Jessie Fecteau, Ruth Redmond, and Mary Downey) hold photos of their sons, each of whom was a CIA covert operative held in a Chinese prison. The date was January 1, 1957, and the three were on their way to China to visit their sons in prisons. (Courtesy of William McInenly)

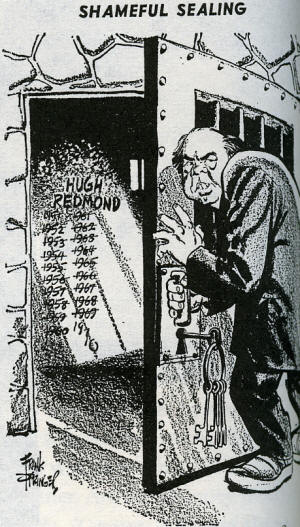

A political cartoon from the July 11, 1970, New York Daily News that appeared after the Chinese reported that Hugh Redmond had committed suicide in one of their prisons. An accompanying editorial suggested what many already suspected -- that Redmond had been murdered or died of neglect. (© New York Daily News, L.P.)