Chapter 4: SaipanAfter a brief refueling stop in Bangkok, the Khampas were again aloft and heading over the South China Sea. Curving north, they arrived at Kadena and were taken to the small CIA compound on the air base for a three-day physical examination. Doctors found them to have well-developed chests and musculature -- no surprise, given their active lifestyles at high altitude. Notable was their low, even pulse rates. A brief aptitude test showed that although none spoke any English, they exhibited good native intelligence. "Being merchants," noted one CIA case officer, "most had a certain sophistication stemming from their contact across the region." [1]

While still on Okinawa, the group was met by the Dalai Lama's brother Norbu, who joined them on the C-118 as they took to the air and veered Southeast. Four hours later, they descended toward a teardrop-shaped island in the middle of the western Pacific. Though the Tibetans were never told the location -- some would later speculate it was Guam -- they had actually arrived at the U.S. trust territory of Saipan. [2]

Situated on the southern end of the Northern Mariana Islands chain, Saipan was of volcanic origin and had an equally violent history of human habitation. Its original population -- seafarers from the Indonesian archipelago -- was virtually wiped out by Spanish colonialists. Later sold to Germany and subsequently administered by Japan as part of a League of Nations mandate, the island -- though no larger than the city of San Francisco -- had taken on extraordinary strategic significance by the time of World War II. This was because Allied strategy in the Pacific hinged on the premise that the Japanese would not surrender until their homeland was invaded. According to Allied estimates, such an invasion would cost an estimated 1 million American lives and needed the support of a concerted air campaign. For this, Washington required a staging base where its bombers could launch and return safely; the Marianas chain, the U.S. top brass calculated, fell within the necessary range.

Before the Allies could move in, however, there remained the thorny problem of removing nearly 32,000 Japanese defenders firmly entrenched on the island. In June 1944, one week after the landings at Normandy, 535 U.S. naval vessels closed on Saipan. In what was to become one of the most hotly contested battles in the Pacific, they blasted the island from afar before putting ashore 71,000 troops.

The Japanese were not intimidated. Having already zeroed their heavy weapons on likely beachheads, they ravaged the landing columns. Some 3,100 U.S. servicemen died; another 13,100 were wounded or missing.

Despite such heavy Allied casualties, the Japanese had it worse. Overwhelmed by the size of the invasion force, some 29,500 defenders perished in the month-long battle to control the island. Of these, hundreds jumped to their deaths off the northern cliffs rather than face the shame of capture.

Once in Allied hands, the Marianas were quickly transformed into their intended role as a staging base for air strikes against Japan. It was from there, in fact, that a B-29 began its run to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Nine days later, Japan surrendered.

Following World War II, the United States remained on hand to administer the Northern Mariana Islands. In July 1947, this role was codified under a trustee-ship agreement with the new United Nations, which specifically gave the U.S. Navy responsibility for the chain. In practice, this trusteeship translated into an exceedingly small U.S. presence. With Japan's wartime population either dead or repatriated, the chain boasted few settlements of any note; only Saipan hosted anything approaching the size of a town. Even its airfields -- which had once been so critical during the War -- now fell largely dormant after being vastly overshadowed by the sprawling U.S. military bases in neighboring Guam and the Philippines.

For the CIA, however, the tranquility of the Marianas held appeal. Looking for a discreet locale to build a Far East camp to instruct agents and commandos from friendly nations, the agency in 1950 established the Saipan Training Station. Officially known by the cover title Naval Technical Training Unit, Saipan station took up much of the island's northern peninsula and featured numerous segregated compounds where groups of Asian trainees from various nations could spend several months in isolation. "We did not even let two classes from the same country know one another," underscored one case officer. [3]

The course work offered at Saipan station ran the gamut of unconventional warfare and espionage tradecraft. By 1956, Chinese Nationalists, Koreans, Lao, and Vietnamese had passed through its gates for commando instruction; a Thai class had been coached as frogmen; and other Vietnamese had been preened to form their own version of the CIA. In some cases, classes consisted of just one or two key individuals who were going to blend into their central government structure. "There were no standard lessons," said one CIA officer. "Each cycle was custom tailored." [4]

None of the prospective trainees presented more of a challenge than the newly arrived Tibetans. The six recruits were to act as the CIA's eyes and ears back inside Tibet, John Reagan explained to the resident instructor cadre. This necessitated that they absorb not only communications and reporting skills but also a general knowledge of guerrilla warfare techniques, as well as a limited understanding of tradecraft. Although such a broad curriculum would normally require a full year, Saipan station was told to ready the subjects in a quarter of that time. [5]

Under such strict time constraints, three different CIA training teams were assembled to begin instruction. The first team offered the Khampas an extremely rudimentary course on classic espionage tactics. The second started coaching them in Morse communications and use of the RS- shortwave radio and its hand-cranked generator. The final team initiated a primer on guerrilla warfare and paramilitary operations.

Very quickly, problems became apparent. Having had almost no schooling, the Khampas had trouble with such essential concepts as the twenty-four-hour clock. They also had difficulty quantifying distances and numbers. Precise reporting would be vital once they were back in the field, emphasized one agency officer, "but too often they tended to use vague descriptions such as 'many' or 'some."' [6]

To overcome some of these challenges, the CIA instructors had to rely on visual demonstrations. "We had to physically show them," said one trainer, "not simply use a classroom." To clarify the construction of ground signals for an aerial resupply, for example, scaffolding was assembled atop the island's northern cliffs. Below, firepots were arranged on the beach so the Tibetans could visualize how they would appear from the air. [7]

Communications training proved even more difficult. The main stumbling block: Khampas traditionally received little formal language instruction. The six students, who were barely able to read or write, could hardly be expected to transmit coherent radio messages. Not realizing the seriousness of this critical deficiency until nearly halfway through the training cycle, the CIA instructors scrambled to find someone who could teach basic Tibetan grammar. Norbu, who was acting as primary interpreter for the other course work, could not be spared for double duty. Neither could Jentzen, Who in any event was weak in language skills.

Enter Geshe Wangyal.

As a result of the unique symbiosis between Tibetan lamas and Mongol khans during centuries past, Tibetan Buddhism had converts spread across the Mongolian steppes of Central Asia. Some of these Mongolians, being a nomadic people, had wandered far with their adopted religion. By the early seventeenth century, one such band had settled in the Kalmykia region of Russia just north of the Caspian Sea.

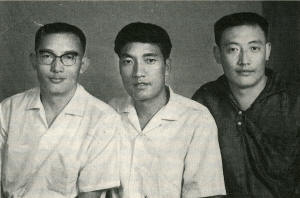

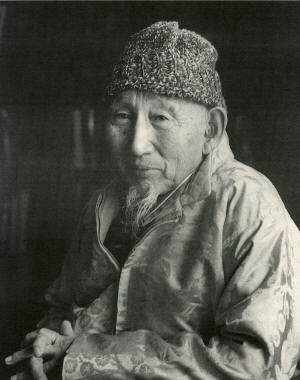

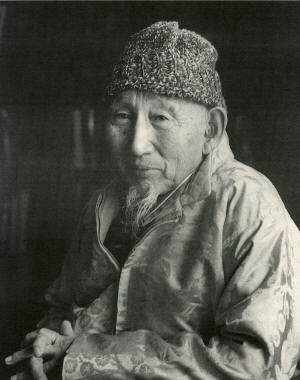

Geshe Wangyal, the CIA's Mongolian translator. (Courtesy Joshua Culter)

Geshe Wangyal, the CIA's Mongolian translator. (Courtesy Joshua Culter)As an ethnic and religious anomaly, the Mongolians were initially ignored by their host country. By the early twentieth century, however, their mastery of Tibetan Buddhism eventually brought them to the attention of the Russian czars. Looking to outwit the British in the great game of colonial competition, the Russians sought to use a particularly gifted Mongolian monk named Agvan Dorzhiev to court favor with Lhasa.

The task proved deceptively easy. A true scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, Dorzhiev (who hailed from a displaced Mongolian clan in Siberia) not only won an introduction to the thirteenth Dalai Lama but also was retained as a palace tutor and confidant for ten years. Through this inside connection, the relationship between Tibet and Russia had the makings of a close alliance. In 1904, however, chances for this were dashed when the Dalai Lama briefly fled to Mongolia following a British incursion from India. Dorzhiev was dispatched to plead for emergency Russian support, but he returned with nothing more than moral encouragement. Having just been humiliated in the Russo-Japanese War, the czar had little time to spare for Tibet.

The Russians never had a chance to make amends. In 1917, the czar was overthrown by Bolshevik communists, and Russia became the Soviet Union. By that time, Dorzhiev had settled among his ethnic relatives in Kalmykia and opened a pair of monastic schools. Tibet never strayed far from his mind, however, and shortly after the Bolshevik revolution he personally selected several of his best pupils to continue their studies in Lhasa. Among them was a prodigy named Wangyal. [8]

Born in 1901, Wangyal had started monastic life at age six. He was known for his ability to memorize several pages of Buddhist text in a single sitting, and he regularly excelled in class. Switching briefly to medical school, he again took top honors before reverting back to religious course work following the untimely death of his professor.

After being selected to study in Lhasa, Wangyal learned that he would be part of a larger expedition with ulterior motives. As the Bolsheviks still harbored the czarist desire to court Tibet, one of his co-travelers was a communist functionary who intended to offer Lhasa weapons as a sign of good faith. Having Moscow's obvious blessing did not ease the physical challenges of journeying to the Tibetan plateau. What was expected to take four months instead took fourteen and claimed the life of one apprentice in a blinding snowstorm.

Once in Lhasa, Wangyal enrolled at the prestigious Drepung Monastic University. Located on a high ridge eight kilometers west of the capital, Drepung had once been the largest monastery in the world (its population in the seventeenth century was a staggering 10,000 monks), Setting his sights high, the newly arrived Mongolian intended to become geshe (doctor of divinity) -- a title that can take up to thirty-five years of study to achieve. [9]

Rigorous study was not Wangyal's only challenge. He ran short of finances and was forced to leave Lhasa in 1932 to seek funds at home. Planning to return by way of China, he got as far as Beijing before hearing stories of Soviet repression back in Kalmykia. This led him to look for an alternative source of financing in Beijing, and eventually he was able to earn a good living translating Tibetan texts.

By 1935, Wangyal had amassed enough cash and headed back toward Tibet via India. Making his way to Calcutta, he had a chance meeting with Sir Charles Bell, a senior British colonial official and noted Tibetan scholar who, ironically, had earlier displaced Agvan Dorzhiev as the closest foreign confidant of the thirteenth Dalai Lama. Given his linguistic skills -- Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, and a smattering of English -- Wangyal was hired as Bell's translator during an extended tour of China and Manchuria.

Following these exhaustive travels -- including a four-month visit to England -- Wangyal finally made it to Lhasa. There he earned his geshe degree after just nine years of study. Though this was an impressive scholastic accomplishment, he found himself under a cloud of suspicion. His foreign heritage, coupled with extended time spent in China and service to the British, did not sit well among the xenophobes of the Tibetan court.

Not fully welcome in the homeland of his religion, Geshe Wangyal limited his time in Lhasa to the summer months. Winters were spent in Kalimpong, where he displayed pronounced entrepreneurial skills as a trader. Although this was financially rewarding, he yearned to open his own religious school. Stonewalled in Tibet, he instead targeted Beijing -- only to cancel those plans when the communists came to power in 1949. Figuring that he would give Tibet a second chance, he again ventured to Lhasa but was forced to flee upon hearing that the PLA was approaching the Tibetan capital in late 1951. [10]

Back in Kalimpong, Geshe Wangyal grew restless. China, Tibet, Mongolia, and his native Kalmykia were all under communist occupation, but wasting away the months in tiny Kalimpong lacked both mental and spiritual stimulation.

There was one attractive alternative, however. In late 1951, the United States accepted 800 Kalmyk Mongolians who had been languishing in refugee camps since the end of World War II. These refugees were drawn from two waves that had fled the Soviet Union during the preceding decades. The first had departed Kalmykia shortly after the Bolshevik revolution; the second left in late 1943 after Joseph Stalin adopted a ruthless line against minorities and started deporting the Mongolians to Siberia aboard cattle cars. Once in the United States, the older wave of emigres settled around Philadelphia. The newer ones -- no more than seventy families -- established a small but vibrant community near Freewood Acres, New Jersey. [11]

Hearing of this, Geshe Wangyal contemplated a move to the United States. His first several visa applications were rejected, and it was not until mid-1954, following introductions by a British acquaintance, that the U.S. vice consul in Calcutta processed his papers with a favorable recommendation. [12]

Arriving on American soil in February 1955, Geshe Wangyal found that word of his religious accomplishments in Tibet had already made him famous among his fellow Kalmyk Mongolians. With an instant audience, he opened a modest temple in a converted New Jersey garage.

Geshe Wangal's fame was not limited to his ethnic home crowd. As the first (and to that time, only) qualified scholar of Tibetan Buddhism in the United States, he soon came in contact with Norbu, who at the time was also living in New Jersey and teaching Tibetan at Columbia University. Out of mutual respect between geshe and incarnation, Norbu was given an honorary chair at the New Jersey temple.

The two cooperated in another way as well. Following Norbu's lead, Geshe Wangyal began teaching languages -- first Mongolian, then Tibetan -- at Columbia University in 1956. Having dissected Tibetan grammar during years of poring over Buddhist texts, he had a particularly deep appreciation for its written form. His extended time as Bell's interpreter had left him with reasonably good English skills. The U.S. government, for one, found his linguistic talents more than adequate: among his first Tibetan students at Columbia were two from the U.S. Army. [13]

Given this background, Geshe Wangyal was the perfect choice to instruct the Khampas about their own language. Having already been indirectly exposed to the U.S. government while teaching the army students -- and after being informed that Norbu was already involved -- the monk offered his cooperation and was soon en route to Saipan.

Beyond the serious language hurdle, the CIA staff on Saipan harbored a more fundamental concern about their Tibetan subjects. The Khampas were Buddhists, and nearly all of them had spent some time as monks. Their instructors wondered whether they would hesitate to kill a fellow human being. For Eli Popovich, chief of the seven paramilitary instructors, this was driven home during an incident early in training. A veteran of OSS operations in Burma and the Balkans, Popovich had been addressing his class when one of the Khampas came forward and pushed him. "I had been standing on an anthill," recalls Popovich, "and he didn't want me interfering with another living entity." [14]

It would take another incident -- also involving ants -- to put the Tibetan attitude toward life and death into better perspective. One morning, case officer Harry Mustakos heard a commotion coming from the latrine, where trainee Tashi (now called "Dick"; each Khampa had an American name on Saipan) was attending to cleaning duties. Beckoned by Norbu, Mustakos rushed in to find both Tibetans hunched over a column of ants crossing from a crack in the wall toward the urinal. "What can we do about these creatures?" Norbu pleaded.

With class set to start in minutes, Mustakos gave them a quick answer. "You can carefully sweep them up and drop them outside, " he said, "or you can continue swabbing the deck as though they weren't there."

The CIA officer left the room to let the two Tibetans discuss a solution. Dick's voice could soon be heard reciting a Buddhist mantra as he rhythmically swung the mop across the trespassing column. "Pragmatism prevailed," concluded Mustakos. [15]

Indeed, the CIA was fast coming to realize that the Khampas had few reservations about taking the life of a Chinese invader. "Their ideas on what weapons should be dropped were starting to get extravagant," remembers Mustakos. "Machine guns for each of their friends, they said, plus artillery batteries would be nice." [16]

Of the six Khampas, Wangdu -- now known as "Walt" -- led the cry for more sophisticated weaponry. Partly, this reflected Walt's hot temper. Partly, too, it was a face-saving gesture to compensate for his low scores in Morse training. "He was near the bottom of the class," said fellow trainee Athar, who now went by the name "Tom." "He began complaining that he wanted to train with bigger guns, not waste time on radios." [17]

For the CIA, this posed a dilemma. Walt's demands for heavier firepower conflicted with its need for skilled agents who would observe and report -- not rush to the offensive. Gingerly, the agency trainers attempted to downplay Tibetan expectations. Said Tom, "They explained that it would be too hard to let us carry artillery pieces into Tibet." [18]

The Khampas were not the only ones who required massaging. The two interpreters -- Norbu and Jentzen -- offered their own set of challenges. Like many Asian societies, Tibet was composed of clearly defined strata, with the religious elite and aristocracy at the top and the warrior and merchant classes well below. On Saipan, this translated into one set of quarters for the interpreters (and, later, Geshe Wangyal) and a different barracks for the students. For the proud Khampas, this arrangement was palatable in the case of Norbu, whose religious standing and family ties demanded reverence. Jentzen, by contrast, was viewed merely as Norbu's servant, who was elite only by association. "His English was not too good," sniffed Tom. [19]

For his part, Norbu did not much care for the cloistered life on Saipan. Limited to a single classroom building and pair of sleeping quarters, the Tibetans were rarely allowed to leave their isolated corner of the training base. Moreover, cooks and cleaning crews were forbidden in the name of operational secrecy. As a result, all present -- trainees as well as interpreters -- were required to rotate chores and eat the same meals. As an incarnation and brother of the Dalai Lama, Norbu found this too much to take and at one point refused the food. The CIA cadre was not amused. "If you don't eat it," said Mustakos sternly, "the students won't eat it." Norbu eventually backed down and consumed his proletarian meal.

The Khampas, by contrast, offered no complaints about the Spartan conditions. With rare exceptions, their health rarely faltered. One scare occurred when trainee Tsawang Dorje -- now going by the name "Sam" -- suffered a ruptured appendix. A few weeks later, the same hapless agent accidentally shot himself in the foot with a pistol. Both incidents required emergency trips to Okinawa, and both resulted in fast recoveries.

On another occasion, Lhotse- -- his name now Americanized to "Lou" -- caught a bad case of dysentery. By chance, CIA Director Allen Dulles was passing through Saipan during a Far East tour and had along his personal physician. From the latter, the local doctor was able to obtain a new drug and get Lou started on a course of treatment. Concerned, the CIA instructors checked with Lou daily to determine if his bowel purges continued.

"Shit today?" they asked. To this, the afflicted agent repeated the words in the affirmative. Convinced that the medication was not taking effect, the CIA instructors sent Lou and an interpreter to the hospital for closer observation. There they learned that Lou had already returned to normal and had merely been reciting the phrase to showcase his newfound command of select English words. [20]

Such medical emergencies aside, the Khampas were shaping up to be model students. "They were new to us," said Mustakos. "Culturally and psychologically, we were learning from them as much as they were learning from us." Sometimes this led to conclusions that bordered on the comical. The Tibetans, for example, saw American omnipotence in seemingly unrelated events. Each night at sundown, the CIA advisers sprayed the compound with an insecticide-dispensing unit mounted on a jeep. This awed the Tibetans, who viewed the routine as proof that the United States was a powerful country. Said case officer Mustakos, "They noted that we had devised ways of killing big things -- like people -- by using the weapons with which we were training, and even killing little things -- like mosquitoes -- with the DDT fogger." [21]

Such innocent observations only served to endear the Tibetans to their CIA instructors. One of the most impressed was Roger McCarthy. Thirty years old, the gregarious McCarthy had joined the CIA in 1952 as a communications specialist for Western Enterprises. Promoted to case officer, he arrived in Saipan in 1956 and had just completed a paramilitary training cycle for six members of the Lao intelligence service prior to the arrival of the Tibetans. "The Lao would get frightened during nighttime operations," he recalls, "and hold each other's hands." The Tibetans, by contrast, were of entirely different mettle. "They were brave and honest and strong," said McCarthy. "Basically, everything we respect in a man." [22]

Training officer Mustakos shared similar sentiments about the rugged Khampas. This was underscored during close-quarter combat instruction when he tossed a traditional short Tibetan sword to Lou and told him to attack. "I learned from that," said Mustakos, "to find out if knife fighting was native lore before trying it again."

After a month-long extension to allow Geshe Wangyal to complete his language instruction, training for the Khampas was all but finished by mid-September. To properly outfit them for their return, an urgent request had been flashed back to India for six sets of used Tibetan peasant garb, knives, and coins. Once Gyalo gathered the items, he rushed down to Calcutta and notified his case officer, John Hoskins. Smuggled into the consulate, the unwashed, reeking load was divided into half a dozen diplomatic pouches and posted to Saipan. [23]

Other preparations were well under way for insertion of the agents back into Tibet. To save time -- and avoid the diplomatic and physical hazards of walking back through Indian territory -- the CIA intended to drop them inside their homeland by parachute. As CIA headquarters had given the cryptonym ST CIRCUS to the emerging Tibet Task Force, this aerial portion of the project retained the same theme and was code-named ST BARNUM. [24]

Airborne infiltration posed a whole range of difficulties. First, it required a discreet staging base within range of Tibet; just as during ex filtration, East Pakistan was the optimal choice. Second, the flight would necessarily be conducted at night, which meant that the plane needed both clear weather and a full moon to negotiate its way to the drop zone. Fortunately, both weather patterns and moon phases were predictable. In East Pakistan, the annual monsoon season came to a close in October, and over Tibet, the clearest skies could be found in October and November. Factoring in a full moon, this meant that premium conditions were most likely to occur during a six-day window beginning 6 October and during another six-day window starting 5 November. [25]

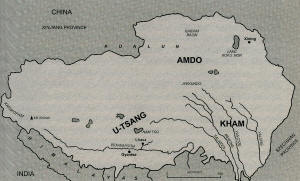

An even greater challenge was determining where in Tibet the agents would be inserted. From the moment the Khampas arrived in Saipan, part of that station's mandate had been to help select drop zones. During debriefings of the trainees, each was quizzed about his hometown, where he had traveled, what routes he had taken, names of villages along the way, and people he had met. Starting from crude route tracings, the CIA instructors slowly added village names, terrain features, and distance notations.

Concurrently, CIA headquarters assigned the Far East Division's air branch to flesh out the details for ST BARNUM. Heading the task was the branch's deputy, Gar Thorsrud. No stranger to covert air support, Thorsrud had been a student at the University of Montana when first approached by a CIA recruiter in the summer of 1951. The recruiter was looking for smoke jumpers, the unique breed of firefighters employed by the U.S. Forest Service. During the dry summer months, these jumpers were on call at rural airstrips across the western half of the United States. When a forest fire flared, they donned parachutes and dropped in small teams ahead of the advancing flames. Using shovels and saws to cut firebreaks, they were responsible for saving thousands of acres of woodland.

For the CIA, smoke jumpers were attractive on a number of counts. Not only were they fit and adventurous, but the job entailed learning the basics about parachuting and air delivery techniques. Smoke jumpers, in fact, were on the leading edge with equipment such as steerable chutes and skills such as rough-terrain jumping. Moreover, many -- like Thorsrud -- were promising college students who volunteered for the task during summer break.

In the spring of 1951, just after his graduation, Thorsrud and another smoke jumper were asked to report early to train a pair of CIA officers in rough terrain parachuting techniques. Upon completion, both were offered CIA employment subject to a security review. By that fall, another eight were recruited and passed the review.

By year's end, the Montana smoke-jumping contingent had departed for the Far East. Once there, they were briefed by agency case officers. Indigenous teams and singleton agents were being readied for insertion into China and North Korea, they were told. Because of their parachuting background, the smoke jumpers were assigned to act as jump masters and "kickers," the descriptive term used for cargo handlers who pushed parachute-equipped supply pallets out the back of transport aircraft.

For the next two years, Taiwan-based smoke jumpers helped deliver agents and kick bundles behind communist lines. Thorsrud was involved in some of the deepest penetrations to supply Muslim guerrillas in western China. But at the end of the Korean War, nearly all the jumpers resigned from the agency for more mundane civilian assignments. Among them was Thorsrud, who joined the Air National Guard for pilot training in anticipation of a career with an airline.

It was not to be. In the summer of 1956, Thorsrud was again contacted by the agency and asked to rejoin the Far East Division's air branch. Weighed against a career as a commercial pilot, the CIA post won.

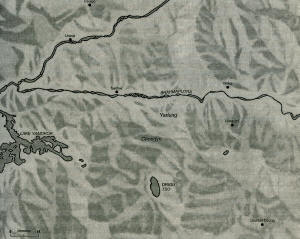

Once he was handed the Tibet assignment, one of Thorsrud's first tasks was to sort out the issue of drop zones. Although the CIA had a special office for worldwide overhead imagery, the files on Tibet were exceedingly thin. Satellites did not yet exist, and the U-2 spy plane -- which had been penetrating the Soviet bloc for just a little over a year -- had flown only a single Tibet overflight on 21 August 1957. Apart from this, few current photographic and cartographic resources were to be found in the agency's archives. [26]

Digging deeper, Thorsrud eventually came up with some useful, albeit dated, photographs. These came from the 1904 British military expedition that had pushed its way into Lhasa to seek a trade agreement. The best shot was a photo of the Brahmaputra River, clearly showing the dunes and extensive wash along its northern bank after flood stage. Just sixty kilometers southeast of the Tibetan capital, this sandy expanse was selected as the site for the first drop.

Based on information coming from Saipan, a second drop zone was chosen near Molha Khashar, a tiny village of two dozen families just outside Lithang. Besides being the hometown of Walt's family, Molha Khashar was reputed to be an area of armed Khampa resistance. [27]

With two drop zones selected, Thorsrud now had to decide on planes and crews. Within the agency's own Asian proprietary -- Taiwan-based CAT -- there was more than sufficient talent. During the Korean War, U.S. crewmen flying for CAT had conducted dozens of drop missions and intelligence-collection flights over mainland China. But after a CAT C-47 was downed over the PRC in November 1952 -- followed by the crash of a covert USAF flight over China in January 1953 -- U.S. crews were forbidden to fly agent infiltrations over the mainland.

An Asian alternative could be found within the ranks of the ROC air force. Back in 1952, five Nationalist pilots and two mechanics had been sent to Japan under CIA auspices. There they began training in low-level flights and drop techniques. By the middle of the following year, the contingent returned home as the cadre of a new Special Mission Team. Initially supplied with a single B-26 and two B-17s on loan from Western Enterprises, the team did not see action until February 1954. That month, the B-26 dropped leaflets over Shanghai to disrupt the fourth anniversary celebrations of the Sino-Soviet Friendship Treaty. That flight was deemed a success, and the team was flying an average of one mainland infiltration per month by the time Thorsrud was planning the Tibet assignment. Its missions included not only leaflet, supply, and agent drops but also electronic-signal collection flights to gather data about the PRC's air defenses. [28]

Although there was no denying the competence of the Nationalist Chinese, their participation was ruled out. This was because the ROC still entertained the notion that Tibet was part of greater China, a position that earned them the scorn of most Tibetans. If Taipei was brought into the fold and word leaked, it would undercut the CIA's relations with the Tibetan resistance.

With Americans and Nationalist Chinese precluded, Thorsrud searched for another option. He eventually found one in an unlikely place. Back in 1949, the CIA had hired two Czech airmen when it needed a deniable crew to drop Ukrainian agents into their homeland. These Czechs had earlier distinguished themselves while flying for the British during the Battle of Britain and had remained in England after their homeland fell to communism. In a variation on this theme, the CIA and British intelligence had jointly prepared a paramilitary operation the following year to unseat the communist government in Albania. Again looking for foreign aircrews, the British had suggested tapping the large pool of Polish veterans in England who had performed brilliantly during World War II. Thus, six stateless Poles from within that community had been hired and dispatched to a staging base in Athens, Greece, for the Albanian assignment.

Pleased with the results, the CIA in 1955 again turned to stateless Poles when it needed crews for a covert operation running out of Wiesbaden, Germany. Using modified P2V Neptune antisubmarine aircraft, missions were flown along the Soviet frontier to collect electronic intelligence. Although Americans piloted many of these flights, two of the planes were flown with Polish crews and used for actual penetrations of Soviet airspace.

It was from this seasoned Polish contingent at Wiesbaden -- code-named Ostiary -- that the Far East Division requested the loan of two five-man crews to perform the Tibetan assignment. The first was to be headed by Captain Franciszek Czekalski, the thirty-six-year-old leader of the Wiesbaden Poles. The second was under Captain Jan Drobny, a former flying sergeant who had flown special wartime drop missions to the anti-Axis resistance movement in Poland.

After gaining agency approval to use Ostiary, Thorsrud had to decide on an infiltration plane. By 1957, the workhorse for covert China overflights from Taiwan was the B-17. The four-engined Flying Fortress had been a fixture of the European theater during World War II. For the CIA's missions over mainland China its ROC-based bombers had been stripped of all weapons and national markings, painted black, and modified with engine mufflers to shield the exhaust. Given its range and maneuverability, it was deemed suitable for ST BARNUM.

In mid-September, the finalized plan was sent to CIA Director Dulles for his signature. Upon his consent, a Taiwan-based B-17 was flown to Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines. [29] Piloting the bomber was Robert Kleyla, one of the officers managing the CIA air fleet in the ROC. Once at Clark, he met up with the two Ostiary crews escorted by their Wiesbaden case officer, Monty Ballew. Though none of the Europeans had ever flown a B-17, they took to the bomber quickly. Acting as instructor, Kleyla gave the Polish captains what turned out to be a pro forma checkout. "They already were well qualified in four engines," he summed up. [30]

Their transition complete, the Ostiary contingent loaded into the lone bomber and ferried it to Okinawa. There they married up with the Tibetans, who had arrived to start airborne training. Much preparation and experimentation had gone into this phase of the operation. Leading the effort was James McElroy, head of the CIA's aerial resupply section at Kadena Air Base. Eighteen years old when he enlisted in 1946, McElroy had been a U.S. Army parachute rigger until seconded to the CIA in 1951. He now oversaw a section of four Americans and ninety Okinawans who were responsible for parachute delivery operations in support of CIA operations across the Far East. [31]

Just prior to the arrival of the Tibetans, McElroy had been contacted by Saipan station with two requests. First, they wanted a parachute with high maneuverability. Second, they needed a system to ensure that a large supply bundle would remain with the jumper. McElroy was told that the drop zone was at an elevation of 4,545 meters (15,000 feet) with no elaboration on the destination.

For the maneuverable parachute, McElroy took a page from the smoke jumpers. During the early 1940s, they had developed a twenty-eight-foot flat-surface chute with modified slots and tails that gave them sufficient steering ability to maneuver near the edge of firestorms. Inspired by this, McElroy back in 1953 had tried to work similar modifications into the military's standard thirty- five-foot T-10 chute. The results had been disappointing, though in hindsight, he realized that the problem was failure to compensate with sufficiently large slots for the bigger army T-10.

This time, McElroy used the same proportions as the smoke jumper prototypes. The new chutes, with bigger slots and longer tails, were tested by McElroy and Saipan training officer Roger McCarthy. After four jumps, they concluded that the modified T-10s had the required steerability.

For the second request -- keeping the bundle close to the jumper -- McElroy had something much more revolutionary in mind. Harkening back to the end of World War II, he recalled seeing a magazine photograph of a row of connected bundles streaming out the door of a C-47. "I wasn't sure if it was ever used in combat," he said, "but I wanted to try something similar." Sketching out his concept, McElroy envisioned a nylon line running from the chest of the jumper to the supply pallet. Static lines would deploy chutes on both the pallet and the parachutist, with a 91-meter line keeping the two connected. If one of the two chutes failed to deploy, the line was designed to break if overstressed. McElroy was confident that the system would work -- at least on paper.

Once the Tibetans arrived, they were given a primer on landing techniques and then outfitted with the modified chutes. Fearless of heights after years of peering off tall canyons, they exited the plane without hesitation. Much to the case officer's delight, they even used the steerable rigs to chase one another in the air. Three jumps later, all were declared qualified.

By that time, they were into the first days of October, and optimal moon and weather conditions were set to begin over Tibet. Before leaving Kadena, the resupply section loaded bundles inside the B-17. Each of the two Tibetan teams would get a single bundle weighing no more than 114 kilos (250 pounds). Included inside was radio gear, extra crystals, and personal weapons. To get this bundle off the drop zone as fast as possible, the CIA logisticians had broken the gear down into 36- kilo (80-pound) segments and placed them inside special pouched vests similar to those used by newspaper delivery men. [32]

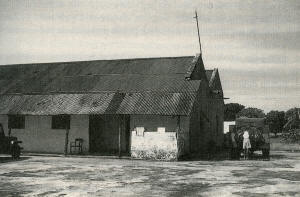

Once their supplies were secured on board, the Tibetans, along with a handful of CIA case officers and both Ostiary crews, took the B-17 to East Pakistan. As with their earlier C-118 ex filtration, the black, unmarked bomber was cleared to land at the unused airstrip at Kurmitola, thirteen kilometers north of Dacca. An Allied runway during World War II, the Kurmitola field was 1,060 meters long, 45 meters wide, and almost 2 meters thick -- all of hand-laid brick. Adjacent to the strip was a hangar with open ends, some empty brick buildings with tin roofs in bad repair, and little else. Because East Pakistan's main north-south road had been built across the center of the runway at a right angle, soldiers from the nearby cantonment were directed to divert traffic at a discreet distance while the B-17 was present. [33]

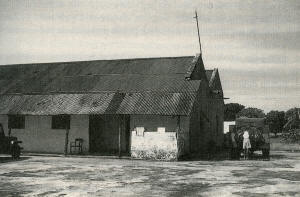

The communications shed at Kurmitola airfield, East Pakistan; the lightning rod at right is where a CIA technician was electrocuted. (Courtesy Walter Cox)

The communications shed at Kurmitola airfield, East Pakistan; the lightning rod at right is where a CIA technician was electrocuted. (Courtesy Walter Cox)As the bomber landed and the case officers disembarked, they were immediately hit by two bits of bad news. First, they learned that a CIA communications technician -- dispatched to Kurmitola the previous week to establish a secure radio link -- had been electrocuted while erecting an antenna. Second, they got word that the Soviets had just bested America and successfully launched the first satellite into Earth orbit. [34]

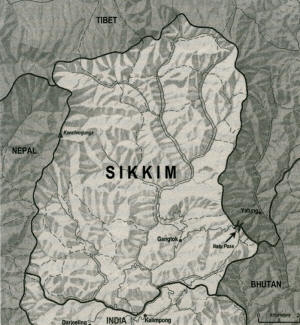

With little time to ponder these developments, the officers immediately set about preparing the B-17 for its drop. Captain Czekalski's five-man team was selected to crew the plane; no Americans were to be on board. To minimize exposure over Tibet, the Poles would conduct both drops on the same flight. Because the plane would need to overfly Indian territory without permission, they had to factor in the radar at Calcutta. Gar Thorsrud had already done his homework and knew that the Indian system had no compensation feature and could be defeated if the B-17 used the Himalayan massif as a radar screen. Flying north over Sikkim, the crew would go as far as the Brahmaputra for the first drop, cut east across the Tibetan plateau to Kham for the second drop, then veer southwest through Indian territory back to East Pakistan. "It would be an easy flight for the Poles," concluded Thorsrud. [35]

Inside the B-17, two supply loads were positioned near the 1.4-meter (54 inch) hatch -- known as a "joe hole" -- located in the bclly of the cabin. The Polish loadmaster for the flight, "Big Mac" Korczowski, reviewed with Roger McCarthy the procedure of placing each bundle over the hole and securing it with restraints.

After a one-day delay (because it was considered inauspicious according to the Tibetan calendar), all six Khampas boarded the aircraft. [36] As Kurmitola had no runway lights, flame pots framed the edges of the runway. Before the plane could take off, however, the weather closed in, and the mission was scrubbed. Three more days of overcast followed, and tension was beginning to mount as the full moon entered its final day.

With just one more chance, the weather finally proved cooperative, and the mission was given the green light. As the Tibetans filed inside the plane and their Buddhist prayers echoed through the cabin, they turned one last time to case officer Mustakos and offered up a Christian tradition. "I had taught them the sign of the cross," said Mustakos, "and now they sought a double blessing."

Lifting off from Kurmitola, Czekalski put the B-17 on a northern heading over the Sikkim corridor. With the Himalayas bathed in a celestial glow, the Ostiary crew climbed over the range and negotiated their way onto the Tibetan plateau.

Inside their homeland for the first time in over a year, the agents readied themselves for the first jump. Despite the altitude and unprcssurized cabin, the Tibetans were not using oxygen bottles; a lifetime of mountain living had acclimatized them to the thin air.

As moonlight reflected off the distant Brahmaputra, two of the agents Tom and Lou, now given the radio call signs Budwood 1 and Budwood 2 -- maneuvered toward the joe hole. Selected as the jumper to be connected to the bundle, Tom adjusted a short section of line near his chest; the remaining 91 meters was rolled and covered with elastic loops on the side of the supplies. "I carried a knife at my side," recalled Tom, "just in case something went wrong."

As the B-17 came over the Brahmaputra, the cockpit crew flashed a signal in the cabin. Facing forward with his feet near the hole, Tom watched as Big Mac yanked the restraints on the supplies. Once the load disappeared out the hatch, the line began to play out from the side of the bundle. A second later, Tom dropped into the void.

The sound of the bomber fast receded, followed by the sound of a dog barking. As Tom looked about to get his bearings, he eyed the bundle and its white cargo chute floating before him. The jumper-to-supply line system was working perfectly. Lou, meanwhile, used his steerable T-10 to follow in Tom's wake toward the approaching sandbank. [37]

Inside the B-17, navigator Franciszek Kot wasted no time plotting an eastern course, while Big Mac hauled the second bundle over the joe hole. When they came upon Kham, however, they found that clear skies had given way to a solid cloud bank. Without any sophisticated navigational systems aboard, the crew had little choice but to abort the second drop and head back to East Pakistan. By that time, the full moon phase had run its course; any further attempts at infiltration would have to wait until the next lunar cycle.

Back inside Tibet, Lou and Tom landed without incident on the wind-blown dunes north of the Brahmaputra. Freeing themselves from their parachute harnesses, they both unstrapped the 9mm Sten submachine guns fixed to their chests and peered into the darkness. Although there was a small settlement of three families just 364 meters (400 yards) away, they received no indication that they had been detected.

Turning their attention to the supply bundle, they broke open the load and started removing the prepacked vests. Since the area around the drop zone consisted of soft earth, they decided to dig seven holes and cache most of their supplies in the immediate vicinity. Before doing so, both changed into traditional Tibetan garb and retained one pistol and one grenade apiece. They also kept one RS-1 radio set and buried the spare.

The next morning, Tom and Lou wandered through the nearby village. Because nomads and traders are common throughout Tibet, the sudden appearance of two strangers aroused no undue suspicion. Mingling with the locals, they overheard talk about their plane passing overhead in the night. None of the villagers suspected that any parachutists had landed, so the pair felt safe waiting two days in the vicinity before taking their radio to the top of an adjacent hill. To their dismay, however, they found that the set had sustained damage in the drop. "The light on the transmitter was very faint," recalled Tom, who had graduated as best radioman among the six trainees. "I tapped a few words but had no way of knowing if it was actually sent." [38]

Leaving the malfunctioning set behind, the pair decided to follow the Brahmaputra. After trekking along its bank for a few hours, they eventually came upon a secluded riverside village near Samye. Pivotal in the history of Tibet, Samye was the site of the monastery where Buddhism was officially inaugurated as the state religion. Because it hosted a constant stream of pilgrims, the arrival of the two outsiders again aroused no attention. "I had the grenade and pistol in my pockets just in case," remembers Tom.

After purchasing horses and some food, the agents reversed direction east toward the Woka valley. Riddled with caves and hot springs, Woka was renowned for its shrines and other meditation sites. But before they could reach this area, the agents chanced upon a band of seven Khampa pilgrims heading toward the Tibetan capital. Tom and Lou were in for a shock. Two of the approaching pilgrims were friends from among their own group of young Khampas that had tailed the Dalai Lama during the Buddha Jayanti. Taking the pair aside, the agents swore them to secrecy and asked that they deliver messages to prominent Khampa trader Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang and Lou's own younger brother, both residing in Lhasa.

As the Khampa entourage continued toward the capital, Tom and Lou returned to their drop zone and unearthed the spare RS-1. Finding it in good working order, the pair tapped out several sentences, briefly outlining their activities over the past ten days.

***

For Irving "Frank" Holober, ten days had been a long wait. A thirty-three-year-old Harvard graduate, he had been serving as head of the Tibet Task Force since late July 1957. Like his predecessor John Reagan, Holober was a China specialist: three years at headquarters as a Chinese translator, then a tour with Western Enterprises, where he helped channel support to Muslims in Amdo. Following that had been a three-year sojourn in Indonesia before assuming Reagan's slot.

From the start, Holober had been beset with problems. Reports were coming in from Saipan that Norbu resented the harsh conditions, especially being forced to eat the same food as the students. As soon as the training cycle concluded, the incarnation and his servant promptly quit the program.

Of far greater concern was the fate of Lou and Tom. From the moment the two agents jumped from the B-17, the CIA had been straining to hear word from their pilot team. After a week had passed, there was growing fear that the pair was lost. With little to do, Geshe Wangyal had been temporarily released from service to return to his New Jersey ministry. As an emergency stopgap, Holober had arranged for help from the National Security Agency (NSA), the U.S. intelligence organization charged with communications intercepts. Based at Fort Meade, Maryland, the NSA agreed to loan the CIA its sole Tibetan linguist, Stuart Buck. [39]

Buck had his work cut out for him. While on Saipan, Geshe Wangyal had taught his Tibetan students a remedial code in which their native script was roughly adapted to the Roman alphabet. But because the six Khampas were not fluent in their own written language, spelling errors in Tibetan were compounded by an inexact Roman transliteration. This is exactly what happened when Tom's message was flashed to CIA headquarters. Trying to make sense of the poor spelling, Buck threw up his hands. "It basically says, 'I'm alive.'"

That was all Holober needed to know. "The entire Far East Division," he recalls, "was electrified." [40]

At Clark Air Base, the Ostiary crews had also been playing a waiting game. Sitting out the remainder of October while the moon ran its phases, they married up with the four remaining Tibetans and moved back to Kurmitola during the first week of November. This time the weather was fully cooperative as the B-17 made a moonlit departure for Kham. [41]

Catching sight of the Lithang River -- which ran past the town of the same name -- the crew dropped low over the hills. As they arrived over what they believed was the vicinity of Molha Khashar, the cockpit flashed a signal to the cabin.

Just as the agents lined up behind the joe hole, Dick hyperventilated and collapsed on the cabin floor. As the loadmaster pulled him to the side, the other three readied themselves for the jump. Repeating the procedure used in the first drop, restraints were pulled from the supply bundle, and it disappeared through the hatch. On the other end of the belly line went Sam, followed by the remaining two agents in quick succession. Reversing course, the B-17 headed back toward East Pakistan with the unconscious Dick still aboard.

Unlike Tom and Lou -- who had landed on a desolate sand flat -- the three Kham agents came down in a hillside of conifers. Landing without injury, they cached their supplies and ascended to the top of a nearby mountain under cover of darkness. There they heard gunfire in the distance as the PLA dueled with Khampa guerrillas.

As dawn broke, Walt took his bearings. To his dismay, he found that the plane had overshot their intended drop zone by some fourteen kilometers. Walking along the high ground into the afternoon, they spotted a lone Khampa tending to five Tibetan ponies. The herdsman was visibly apprehensive as the agents approached, though he eventually agreed to escort them to a guerrilla encampment on a neighboring hill.

By nightfall, the three agents had successfully linked up with the rebel band, which coincidentally included Walt's older brother. Together, they headed back to their cache site and retrieved their gear, and just forty-eight hours after infiltration, they radioed word of their safe arrival. ST CIRCUS was off to a good start.