Online Harassment

BY MAEVE DUGGAN

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Summary of Findings

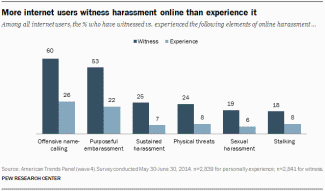

Harassment—from garden-variety name calling to more threatening behavior— is a common part of online life that colors the experiences of many web users. Fully 73% of adult internet users have seen someone be harassed in some way online and 40% have personally experienced it, according to a new survey by the Pew Research Center.

Pew Research asked respondents about six different forms of online harassment. Those who witnessed harassment said they had seen at least one of the following occur to others online:

60% of internet users said they had witnessed someone being called offensive names

53% had seen efforts to purposefully embarrass someone

25% had seen someone being physically threatened

24% witnessed someone being harassed for a sustained period of time

19% said they witnessed someone being sexually harassed

18% said they had seen someone be stalked

Those who have personally experienced online harassment said they were the target of at least one of the following online:

27% of internet users have been called offensive names

22% have had someone try to purposefully embarrass them

8% have been physically threatened

8% have been stalked

7% have been harassed for a sustained period

6% have been sexually harassed

In Pew Research Center’s first survey devoted to the subject, two distinct but overlapping categories of online harassment occur to internet users. The first set of experiences is somewhat less severe: it includes name-calling and embarrassment. It is a layer of annoyance so common that those who see or experience it say they often ignore it.

The second category of harassment targets a smaller segment of the online public, but involves more severe experiences such as being the target of physical threats, harassment over a sustained period of time, stalking, and sexual harassment.

Of those who have been harassed online, 55% (or 22% of all internet users) have exclusively experienced the “less severe” kinds of harassment while 45% (or 18% of all internet users) have fallen victim to any of the “more severe” kinds of harassment. Online harassment tends to occur to different groups in different environments with different personal and emotional repercussions.

Four-in-ten internet users are victims of online harassment, varying degrees of severity. Among all internet users, the % who have experienced harassment or not and the % who have experienced more vs. less severe forms of harassment ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

In broad trends, the data show that men are more likely to experience name-calling and embarrassment, while young women are particularly vulnerable to sexual harassment and stalking. Social media is the most common scene of both types of harassment, although men highlight online gaming and comments sections as other spaces they typically encounter harassment. Those who exclusively experience less severe forms of harassment report fewer emotional or personal impacts, while those with more severe harassment experiences often report more serious emotional tolls.

Key findings

Who is harassed: Age and gender are most closely associated with the experience of online harassment. Among online adults:

Young adults, those 18-29, are more likely than any other demographic group to experience online harassment. Fully 65% of young internet users have been the target of at least one of the six elements of harassment that were queried in the survey. Among those 18-24, the proportion is 70%.

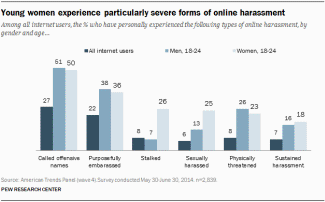

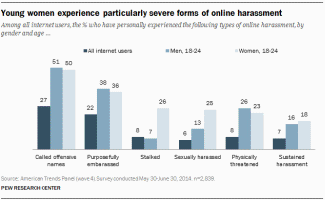

Young women, those 18-24, experience certain severe types of harassment at disproportionately high levels: 26% of these young women have been stalked online, and 25% were the target of online sexual harassment. In addition, they do not escape the heightened rates of physical threats and sustained harassment common to their male peers and young people in general.

Young women experience particularly severe forms of online harassment

Among all internet users, the % who have personally experienced the following types of online harassment, by gender and age ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

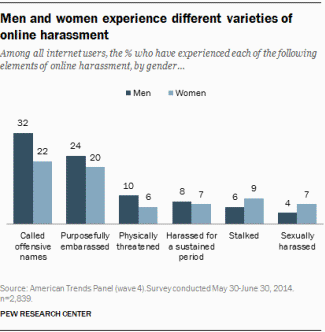

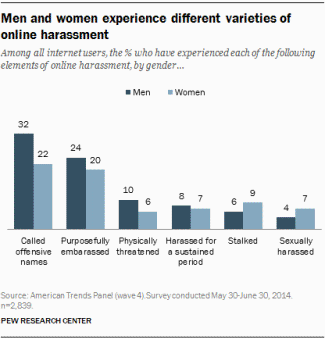

Men and women experience different varieties of online harassment.

Among all internet users, the % who have experienced each of the following elements of online harassment, by gender ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Overall, men are somewhat more likely than women to experience at least one of the elements of online harassment, 44% vs. 37%. In terms of specific experiences, men are more likely than women to encounter name-calling, embarrassment, and physical threats.

Beyond those demographic groups, those whose lives are especially entwined with the internet report experiencing higher rates of harassment online. This includes those who have more information available about them online, those who promote themselves online for their job, and those who work in the digital technology industry.

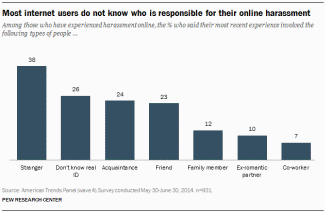

Perpetrators of online harassment: A plurality of those who have experienced online harassment, 38%, said a stranger was responsible for their most recent incident and another 26% said they didn’t know the real identity of the person or people involved. Taken together, this means half of those who have experienced online harassment did not know the person involved in their most recent incident. [1]

Where harassment occurs: Online harassment is much more prevalent in some online environments than in others. Asked to recall where their most recent experience took place:

66% of internet users who have experienced online harassment said their most recent incident occurred on a social networking site or app

22% mentioned the comments section of a website

16% said online gaming

16% said in a personal email account

10% mentioned a discussion site such as reddit

6% said on an online dating website or app

Women and young adults were more likely than others to experience harassment on social media. Men—and young men in particular—were more likely to report online gaming as the most recent site of their harassment.

Responses to online harassment: Among those who have experienced online harassment, 60% decided to ignore their most recent incident while 40% took steps to respond to it. Those who responded to their most recent incident with online harassment took the following steps:

47% of those who responded to their most recent incident with online harassment confronted the person online

44% unfriended or blocked the person responsible

22% reported the person responsible to the website or online service

18% discussed the problem online to draw support for themselves

13% changed their username or deleted their profile

10% withdrew from an online forum

8% stopped attending certain offline events or places

5% reported the problem to law enforcement

Regardless of whether a user chose to ignore or respond to the harassment, people were generally satisfied with their outcome. Some 83% of those who ignored it and 75% of those who responded thought their decision was effective at making the situation better.

Those with more “severe” harassment experiences responded differently to their most recent incident with harassment than those with less “severe” experiences. Those who have ever experienced stalking, physical threats, or sustained or sexual harassment were more likely to take multiple steps in response to their latest incident than those who have only experienced name-calling and embarrassment, 67% vs. 30%. They are more likely to take actions like unfriending or blocking the person responsible, confronting the person online, reporting the person to a website or online service, changing their username or deleting their profile, and ending their attendance at certain offline events and places.

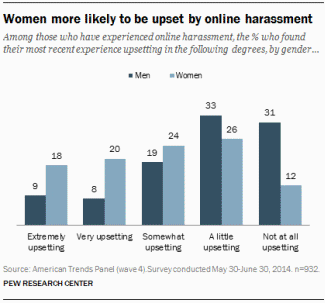

After-effects of online harassment: Asked how upsetting their most recent experience with harassment was, the responses ran a spectrum from being quite jarring to being of no real consequence:

14% of those who have experienced online harassment found their most recent incident extremely upsetting

14% found it very upsetting

21% said it was somewhat upsetting

30% reported it was a little upsetting

22% found it not at all upsetting

Taken together, half found their most recent experience with online harassment a little or not at all upsetting. But a significant minority, 27%, found the experience extremely or very upsetting.

Women were more likely than men to find their most recent experience with online harassment extremely or very upsetting—38% of harassed women said so of their most recent experience, compared with 17% of harassed men.

Again, there were differences in the emotional impact of online harassment based on the level of severity one had experienced in the past. Some 37% of those who have ever experienced sexual harassment, stalking, physical threats, or sustained harassment called their most recent incident with online harassment “extremely” or “very” upsetting compared with 19% of those who have only experienced name-calling or embarrassment.

When it comes to longer-term impacts on reputation, there is a similar pattern. More than 80% of those who have ever been victim of name-calling and embarrassment did not feel their reputation had been hurt by their overall experience with online harassment. Those who experienced physical threats and sustained harassment felt differently. About a third felt their reputation had been damaged by their overall experience with online harassment. Overall, 15% of those who have experienced online harassment said it impacted their reputation.

Mixed feelings toward online environment

When asked to think of their online experiences vs. offline experiences, the % of internet users who agreed or disagreed that the online environment allows people to be …

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,849. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Perceptions of online environments: To explore the context that informs online harassment, respondents were asked about their general perceptions of and attitudes toward various online environments.

Fully 92% of internet users agreed that the online environment allows people to be more critical of one another, compared with their offline experiences. But a substantial majority, 68%, also agreed that online environments allow them to be more supportive of one another. Some 63% thought online environments allow for more anonymity than in their offline lives.

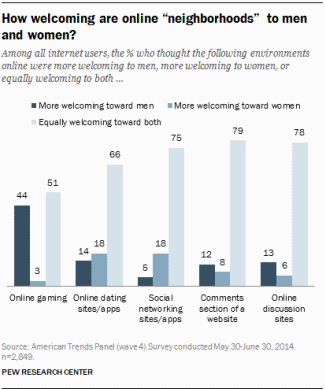

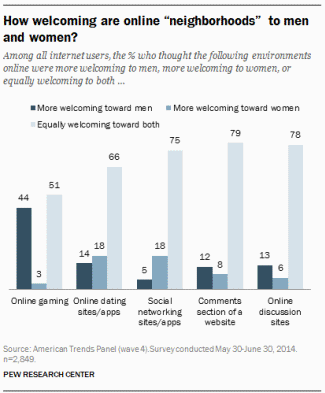

How welcoming are online "neighborhoods" to men and women?

Among all internet users, the % who thought the following environments online were more welcoming to men, more welcoming to women, or equally welcoming to both ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Respondents were asked whether they thought a series of online platforms were more welcoming toward men, more welcoming toward women, or equally welcoming to both sexes. While most online environments were viewed as equally welcoming to both genders, the starkest results were for online gaming. Some 44% of respondents felt the platform was more welcoming toward men.

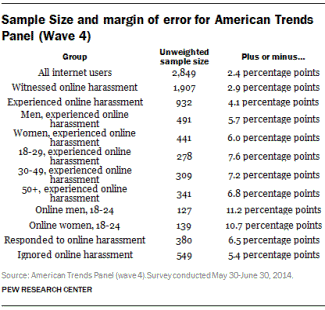

About this survey

Data in this report are drawn from the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel, a probability-based, nationally representative panel. This survey was conducted May 30 – June 30, 2014 and self-administered via the internet by 2,849 web users, with a margin of error of plus or minus 2.4 percentage points. For more information on the American Trends Panel, please see the Methods section at the end of this report.

Introduction

For all the benefits it bestows, the internet has a dark side. Recently, much attention has centered on online harassment. It is a phenomenon that can take a variety of forms: name-calling, trolling, doxing, open and escalating threats, vicious sexist, racist, and homophobic rants, attempts to shame others, and direct efforts to embarrass or humiliate people. While some accept online harassment as a nuisance, others face situations that prompt them to take serious action and precautions.

At a basic level, there is no clear legal definition of what constitutes “online harassment.” Traditional notions of libel, slander, and threatening speech are sometimes hard to apply to the online environment. In addition, the anonymous and pseudonymous nature of the internet can make it easy for people to attack others without repercussions.

Further, there is little consensus as to who should be responsible for monitoring bad behavior online. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 does not hold website administrators liable for content posted by users. Websites and other technology companies claim monitoring bad behavior is economically challenging. Many sites utilize “community standards” or self-reporting mechanisms to bring inappropriate behavior to their attention. However, these efforts have often been seen as unsatisfactory or ineffective. This was evident when Zelda Williams, the daughter of the recently deceased comedian Robin Williams, shut down her Twitter account after a barrage of insensitive comments and abuse related to her father’s suicide became overwhelming to her.

Zelda Williams ultimately reinstated her account following the intervention of Twitter executives, but this issue has recently become the focus of female journalists and commentators who have shared similar stories of harassment, bigotry, and threats in various online spaces. Journalist Amanda Marcotte recently shut off “mentions” on her Twitter feed—the ability of other users to tag each other in their tweets—after feeling defeated from years of harassment. Soraya Chemaly, a media critic and activist, recently outlined why online harassment is uniquely harsh and cruel to women. Jill Filipovic detailed her experience with how easily online harassment becomes offline harassment. Game developer Zoe Quinn and video game critic Anita Sarkeesian were forced to leave their homes after harassment surrounding what’s called #Gamergate, where the tension between the traditional “boys club” mentality of gaming and a growing call for gender parity in the community came to a head. As the controversy escalated, Ms. Sarkeesian was forced to cancel an appearance at Utah State University when she did not feel security under Utah’s gun laws would be adequate after receiving a “school shooting” threat. Amanda Hess, a freelance writer, argued that online harassment creates a “chilling effect” whereby women are disinclined to participate professionally, socially, or economically online.

The sexual nature of many of these incidents is a running thread through these journalists’ stories. The most recent release of private, nude photographs of celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence, Kate Upton, and Rihanna sparked a debate over expectations of security and responsibility online. Many commentators likened the release to revenge porn, in which nude or Photoshopped photos and videos of women are published on the internet, typically by way of a disgruntled ex-partner or spouse. Efforts by activists like Charlotte Laws, whose daughter was a victim of revenge porn, highlight the difficulty in regaining control of one’s image from the digital Pandora’s Box in an area with little legal precedent and resources.

At the same time, a number of prominent websites have begun to review their practices surrounding harassment. Twitter vowed to improve its policies after the Zelda Williams fallout, reassessing how to provide support for those harassed beyond their “Report Abuse” button. In the meantime, third-party software developers at the Electronic Frontier Foundation released “Block Together,” an app that allows Twitter users to block accounts and share lists of troublesome users. Last year, Facebook set up a new review process for pages and groups to determine if their content was too offensive for advertisements. Gaming company Riot Games assessed the abuses woven throughout their community and instituted new participation standards and mechanisms for players to police one another.

While these stories provide insights into online harassment, there has been little data about the prevalence of harassment online, when, how, and to whom it occurs, and its impact on victims. Much of the existing research focuses on teens, a group considered particularly vulnerable to bullying and whose social lives increasingly incorporate digital means. The Pew Research Center has examined issues such as kindness and cruelty and privacy on social media within the teen population. Some have argued that teens may have more resources than adults when it comes to online harassment, such as parents, teachers, coaches, school administrators, and others who can provide guidance and aid. When it comes to adults, if the steps one can take personally do not go far enough to end the harassment, local law enforcement is typically the only other option. But some research has argued that law enforcement agencies are either incapable or unwilling to take on such a complex world.

This is the context for the following study by the Pew Research Center. It is based on survey data from the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. The first part of this report explores the incidence and demographics of online harassment. Part 2 describes perceptions of online environments and where online harassment takes place. Part 3 outlines how people responded to their online harassment. In Part 4, the emotional aftermath of online harassment is explored. Part 5 concludes the report by examining the incidence and demographics of witnessing harassment online.

Part 1: Experiencing Online Harassment

Forty percent of adult internet users [2] have personally experienced some variety of online harassment. In this study, online harassment was defined as having had at least one of six incidents personally occur:

27% of internet users have been called offensive names

22% have had someone try to purposefully embarrass them

8% have been physically threatened

8% have been stalked

7% have been harassed for a sustained period

6% have been sexually harassed

Name-calling and efforts to purposefully embarrass someone are the most frequent forms of online harassment. Among those who have experienced some type of online harassment, two-thirds said that they had experienced name-calling and 54% were the target of embarrassment. For those who have only experienced one type of online harassment, some 81% indicate that their single experience involved name calling or purposeful embarrassment. In addition, these two elements also tend to occur alongside other, more serious examples of harassment. For instance, 80% of those who have experienced sexual harassment online have also been called offensive names and 63% have been purposefully embarrassed by someone online.

Put differently, online harassment falls into two distinct yet frequently overlapping categories. Name-calling and embarrassment constitute the first class and occur widely across a range of online platforms. The second category includes less frequent—but also more intense and emotionally damaging—experiences like sexual harassment, physical threats, sustained harassment, and stalking.

The rest of this report will explore these two categories of harassment in terms of the groups they impact, the online environments in which they occur, and the emotional and personal repercussions they produce.

Demographics of Online Harassment

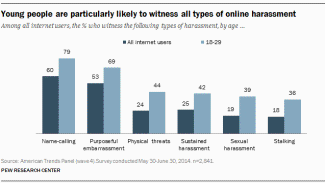

Young people are the most likely demographic group to experience online harassment; men and women experience different varieties.

The level and intensity of harassment that people face online breaks down along a number of demographic lines.

Men and women experience different varieties of online harassment

Among all internet users, the % who have experienced each of the following elements of online harassment, by gender ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Online men are somewhat more likely than online women to experience some level of online harassment overall. Some 44% of men and 37% of women have experienced at least one of the six types of harassment. Men are somewhat more likely than women to experience certain less severe forms of harassment like name-calling and being embarrassed. At the same time, online men are also slightly more likely to have received physical threats. While the differences are small, women are significantly more likely than men to report being stalked or sexually harassed on the internet. Name-calling and purposeful embarrassment are the most common forms of harassment experienced by both men and women alike.

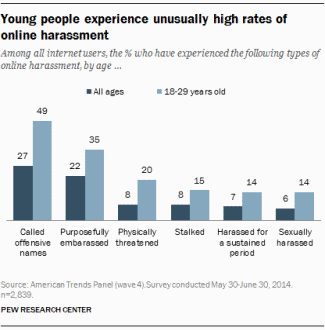

Young people experience unusually high rates of online harassment

Among all internet users, the % who have experienced the following types of online harassment, by age ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Harassment occurs among all age groups, but it is especially prevalent among younger adults. Some 65% of internet users ages 18-29 (and 70% of those ages 18-24) have experienced some type of harassment online.

The youngest internet users, those ages 18-24, are particularly likely to say they are targets of some of the more severe kinds of harassment. Almost a quarter, 24%, have received physical threats. Some 19% have been the target of sexual harassment. Another 17% have been harassed for a sustained period of time.

Online harassment is especially pronounced at the intersection of gender and youth: women ages 18-24 are more likely than others to experience some of the more severe forms of harassment. They are particularly likely to report being stalking online (26% said so) and sexually harassed (25%). In addition, they are also the targets of other forms of severe harassment like physical threats (23%) and sustained harassment (18%) at rates similar to their male peers (26% of whom have been physically threatened and 16% of whom have been the victim of sustained harassment). In essence, young women are uniquely likely to experience stalking and sexual harassment, while also not escaping the high rates of other types of harassment common to young people in general.

Stalking and sexual harassment are more prevalent among young women than among young men. But they are also more prevalent among young women than among women even a few years older (those ages 25-29). Women ages 18-24 who use the internet are more than twice as likely as women ages 25-29 to have experienced sexual harassment online (25% vs. 10%) and three times as likely to have been stalked online (26% vs. 8%). In addition, they are twice as likely as that older cohort to have been physically threatened (23% vs. 11%) and twice as likely to have been harassed for a sustained period of time (18% vs. 8%).

Young women experience particularly severe forms of online harassment

Among all internet users, the % who have personally experienced the following types of online harassment, by gender and age ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

African-American and Hispanic [3] internet users are more likely than their white counterparts to experience harassment online. Some 51% of African-American internet users and 54% of Hispanic internet users said they had experienced at least one of the six harassment incidents, compared with 34% of white internet users.

Open-end responses: Politics and religion

Throughout this report, some of the most compelling comments from open-ended questions about online harassment will be featured. Respondents were asked to describe their most recent experience and their answers ranged from simple phrases like “on Facebook” to detailed accounts of disturbing encounters. Here is a selection of insights from respondents who said they were called names or otherwise harassed for expressing political or religious opinions.

“Through social media, and especially when commenting on controversial issues, often my difference of opinion from others would result in those who do not agree insulting and berating instead of arguing their point respectfully.”

“While commenting on a sensitive religious feminist issue, I was attacked because of my opinion and some of the other commenters resorted to name-calling in their anger.”

“On Facebook, a few days ago, I expressed my feelings about present issues and was harassed and called names. Of course there were not substantive arguments—just judgmental, harsh name calling.”

“I have been ridiculed for my religious and political beliefs.”

“Nothing major, just banter on a political discussion board. I view it as a badge of honor – usually means I made my point well when there is nothing left to say other than name calling.”

“Folks with different views would rather throw names than discuss real issues.”

“Someone has tried to embarrass me for my social views (but I am pretty good at defending myself, so no worries).”

“Just aggressive responses to my post in the politics section of the forum I visit. I really know better – nobody changes their mind based on something they read on an internet forum.”

“Someone didn’t like a comment I made about their post about Obamacare. I pointed to facts I don’t think he knew about so he called me an idiot and said I had no idea what I was talking about.”

“I’ve been called all sorts of names online in response to my being Jewish, and in response to my politically conservative views.”

“I am a strong supporter of LGBTQ persons. I’ve been invited to leave my church and start my own gay/lesbian church.”

“Just name calling because I don’t support Obama policies and occasionally get accused of being racist.”

“Someone asked me what my views were on a topic, gay marriage. I knew they didn’t want to know what I thought and tried to steer away from the topic. The person wouldn’t drop it and I eventually said, ‘I leave the situation up to the voters, but my personal belief is marriage is defined by one man and one woman.’ They then went into how I should be ashamed to be, ‘a f*****g intolerant right wing racist bigot.’”

“I am constantly attacked on gun control as recent as the police shootings and the shooting across from diner in Walmart.”

“Every time I say something in favor of the President I get called all kinds of names.”

“Attacks by Obama supporters who have nothing else but insults. I was called a racist on a blog for criticizing administration lies.”

“A person whose political opinion I disagreed with told me that I should punch myself in the face and that if I didn’t do it good enough he’d come and take care of it for me.”

“When I expressed disagreement with some of the core concepts of contemporary feminism (Rape Culture, privilege, toxic masculinity, etc.), any feminist who doesn’t already know me has been quick to characterize me as a privileged, misogynistic rape apologist.”

“Name-calling for my pro-life stance online.”

‘While tweeting about a woman’s right to an abortion I was viciously harassed by numerous pro-life supporters.”

“I was called names by right-wing Facebook trolls. Since they can’t stand on their ideas, they feel they have to call names and belittle.”

“My Democrat brother chewed me on [a] Facebook political post and I reminded him I’d fight to the death for his right to disagree with me.”

Lifestyle Qualities and Online Harassment

Those who weave the internet more tightly into their daily lives report higher levels of online harassment.

A number of non-demographic factors are also associated with whether or not someone has experienced harassment online. Put simply, those who live out more of their lives online—whether for work, pleasure, or both—are more likely to experience harassment.

Respondents answered three questions about lifestyle, both online and off, that may contribute to a closer proximity to online harassment in general.

Some internet users share more about themselves online than others, on personal or professional topics. Some 12% of internet users said there was a lot of information available about them online, 40% said some was available, another 40% said a small amount was available, and finally 7% reported there was no information available about them online.

Among the half of internet users who said there was a lot or some information about them available online, there was a small but statistically significant difference between them and those with a little or no information available. Some 43% said they had experienced at least one of the six incidents of harassment. This is a bit more than the 38% of internet users who said there was a little or no information about them online.

A portion of jobs in America require self-promotion and sharing of personal information online, but for some that comes with a cost. Among the 21% of employed internet users who need to market themselves online as a part of their job, almost half, 48%, said they had experienced online harassment. This compares with 38% of those who do not need to market themselves online for their job.

The type of job a person holds is also relevant to their experiences with online harassment. Digital technology workers (17% of the employed internet users in our sample) are more likely to report experiencing online harassment.

Almost half of those internet users who work in the digital technology industry (48%) said they had experienced online harassment. This compares with 39% of those who do not work in the digital technology industry.

Across all three of these lifestyle traits, offensive name-calling and attempts to make someone embarrassed were the most common online harassment experiences. Those who work in the digital technology industry experienced name-calling at a rate of 39%, along with 32% of those who market themselves online for their job and 29% of those who say there is a lot or some information available about them online. Roughly a quarter, 27%, of those who professionally market themselves online were on the receiving end of efforts to be purposefully embarrassed, along with 24% of those who say there is a lot or some information available about them online and 24% of those who work in the digital technology industry.

Part 2: The Online Environment

As previous work from Pew Research has shown, most technology users feel positively connected to the services and devices that connect them to others. It is not, however, a relationship without tension. Many users sometimes feel stressed by their constant connectivity (for example when their cell phones distract or interrupt them) or vulnerable when they consider privacy trade-offs.

Building on this knowledge, two series of questions on this survey were designed to understand the specific context in which people may interpret online harassment. The first series examined how harassment might be tied to anonymity, criticism, and social support in respondents’ online and offline worlds. The second series was designed to prompt respondents to think of how welcoming they perceive various online platforms to be toward men and women.

Anonymity, Criticism, and Support Online

Internet users observe criticism and anonymity more online than in their offline lives, but they also witness more support of one another.

Mixed feelings toward online environment

When asked to think of their online experiences vs. offline experiences, the % of internet users who agreed or disagreed that the online environment allows people to be ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,849. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

As a rule, people think the online environment is more enabling of anonymity and criticism when compared with the offline environment. Yet, they also think the online environment is more inviting of social support for users, compared with the offline world.

Specifically, respondents were asked to think of their online experiences compared with their offline experiences and whether the online environment allows people to be more anonymous. Some 63% agreed that the online environment was more enabling of anonymity than the offline environment, while 36% did not agree.

Respondents were then asked if the online environment allows people to be more critical of others, compared with their offline experiences. Fully 92% agreed that the online environment was more enabling of criticism, while only 7% did not agree.

Finally, respondents were asked if the online environment allows people to be more supportive of others compared with their offline experiences. Some 68% said the online environment was more enabling of social support while 31% did not agree.

Open-end responses: Anonymity and criticism

In open-end responses detailing their experiences with online harassment, a recurring theme emerged about how respondents feel anonymity online allows people chances to be cruel.

“Cowards hiding beyond a keyboard and the anonymity the internet provides were verbally abusive.”

“A disagreement in a chat…people are 10 feet tall and bullet proof behind a screen.”

“In college some girls I didn’t get along with created fake email accounts and sent me nasty, harassing emails and instant messages, and also posted harassing anonymous comments on my blog.”

“People who disagree acting out in ways that would never be acceptable when dealing with someone in person.”

On the issue of criticism, a number of the open-end responses highlighted how “people are just mean online sometimes.”

“People just like drama and online is the easiest place for it.”

“Just offensive name calling which most of the time I ignore and move on.”

“Just someone being rude.”

“Guy just being nasty.”

“The way they talk very rude they don’t care if they hurt others feelings.”

Friendliness Toward Men and Women on Different Digital Platforms

Most online environments are seen as equally welcoming toward men and women; the exception is online gaming.

When internet users were asked for their general impressions of how friendly various online platforms were to men and women, most perceived them to be equally welcoming to both genders.

Respondents were asked about online gaming, online dating sites and apps, social media sites and apps, the comments sections of websites, and online discussion sites like reddit. They indicated if they thought each was more welcoming toward men, more welcoming toward women, or equally welcoming toward both.

How welcoming are online "neighborhoods" to men and women?

Among all internet users, the % who thought the following environments online were more welcoming to men, more welcoming to women, or equally welcoming to both ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=2,839. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

By far the starkest results were for online gaming. Fully 44% of internet users believe online gaming is more welcoming to men, while just 3% believe it is more welcoming toward women. Half believe it is equally welcoming to men and women, a proportion much lower than any of the other environments. While most online women believed online gaming was equally welcoming to both genders (55%), a substantial minority believed it was more welcoming to men (40%). Men were more likely than women to think online gaming was more welcoming to men, 49% vs. 40%.

Fully 75% of internet users think social networking sites and apps are equally welcoming to both genders. This compares with 18% who thought they were more welcoming to women and 5% who said they were more welcoming to men.

Much like social media, online dating sites and apps were seen as equally welcoming to both sexes overall, with a minority finding the platform more welcoming to women. Some 66% of internet users found online dating equally welcoming to men and women, while 18% thought it was more welcoming to women. Online dating, however, was seen as more welcoming to men than social media. Some 14% of internet users responded online dating sites were more welcoming to men.

Almost four-in-five internet users felt that discussion sites like reddit and the comments section of a website were equally welcoming to both sexes (78% and 79%, respectively). A minority felt these environments were more welcoming toward men than women, 13% and 12%, specifically.

Across all the neighborhoods, those under 50, particularly those 18-29, were more likely to see differences towards men and women in the atmospheres on these platforms.

Harassment in Different Online “Neighborhoods”

Social media sites are the most common place people experience harassment online.

Different online platforms have various user bases, reputations, and customs. The prevalence of online harassment in these online “neighborhoods” varies significantly. The 40% of internet users who had ever been the target of online harassment were asked to think about their most recent experience and indicate where that experience happened (totals add to more than 100% because respondents were allowed to choose multiple responses):

66% of internet users who have experienced online harassment said their most recent incident occurred on a social networking site or app

22% named the comments section of a website

16% named online gaming

16% said it occurred via a personal email account

10% said it was on a discussion site such as reddit

6% said it happened on an online dating website or app

Social networking sites and apps are a particularly popular online platform. Their popularity with younger internet users is especially tied to the high incidence of online harassment on social media sites and apps.

Fully 72% of those under age 50 who have experienced online harassment said that their most recent experience occurred on social media (including 74% of those 18-29 and 70% of those 30-49). This is a statistically significant difference compared with those over age 50, 44% of whom cited social media as the location of their most recent experience with online harassment.

Open-end responses: Social media

When asked to elaborate on their most recent experience with online harassment in their own words, respondents often described events on social networking sites.

“I was harassed and threatened through messages and comments on my Facebook page.”

“I had someone use Facebook to try to spread nasty rumors about me.”

“Someone was not happy with something I posted on my Facebook, and tried to get me to remove it and when I would not they got angry and called me dirty names.”

“An old ‘friend’ of mine found me on FB and used inappropriate language to describe me and another old friend of mine. I asked him to stop but he didn’t, I had to block him so he would stop disturbing me.”

“A person didn’t like a comment I made on a post and threatened me and called me names.”

“Someone called me a bad name over social media.”

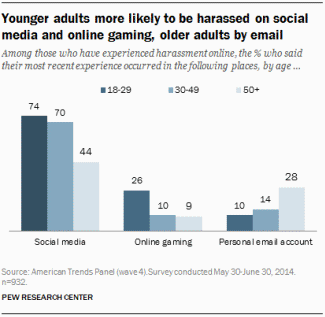

Younger adults more likely to be harassed on social media and online gaming, older adults by email

Among those who have experienced harassment online, the % who said their most recent experience occurred in the following places, by age ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=932. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Those ages 50 and older who have experienced online harassment were particularly likely to say their most recent incident occurred via a personal email account. Some 28% of those 50 and older said so, compared with 12% of those.

Women more likely to be harassed on social media, men during online gaming and in comments sections

Among those who have experienced harassment online, the % who say their most recent experience occurred in the following places, by gender ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=932. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

On the opposite end of the age spectrum, young adults who have been harassed were particularly likely to cite online gaming as the scene of their most recent harassment experience. Some 26% of those ages 18-29 who have experienced online harassment (and 31% of those 18-24) said that their most recent experience occurred within an online gaming environment. This is largely driven by the experience of young men—fully 34% of men ages 18-29 who have encountered online harassment noted that their most recent experience took place within online gaming, the highest of any age and gender combination.

Women were particularly likely to cite social networking sites and apps as the scene of their most recent incident with online harassment. Fully 73% of women who have experienced online harassment said their most recent incident occurred on social networking sites or apps, compared with 59% of men. Men were more likely to cite the comments section of a website as the site of their most recent harassment – 21% of harassed men vs. 11% of harassed women.

Open-end responses: Online gaming

In the open-ended comments from respondents, experiences with harassment and online gaming mostly came down to “sore losers” and name-calling. Many respondents easily brushed off the negativity.

“Someone was a sore loser in an online game and hurled threats and insults.”

“Nothing bad just someone didn’t like how I was playing a game. The good thing is, on the computer, you can just leave!”

“When someone is losing a game, the opponent will abruptly leave but not without calling me or others a vulgar name or comment.”

“A standard bully-type came into a video game broadcast that a friend of mine and I run and made offensive comments at the two of us, mostly referring to our breasts.”

“This happens too regularly in online games to remember a specific occurrence.”

Who Are Online Harassers?

Half of those who have been harassed do not know the person involved in their most recent incident.

In addition to gaining a deeper understanding of where harassment is occurring online, this survey also sought to gain insight into who is responsible for these experiences.

Respondents were again asked to think about their most recent experience with online harassment and indicate who was involved (respondents were allowed to select more than one answer). A plurality (38%) said that the source of their harassment was a stranger, and another 26% said that they didn’t know the real identity of the person or people involved. Taken together, half of those who have experienced some type of harassment do not know the person or people involved in their most recent experience. [4]

Among known perpetrators, acquaintances and friends were the most common types. Almost a quarter, 24%, of those who have experienced harassment said their most recent incident involved an acquaintance. Another 23% said it involved a friend. Family members were less frequently cited, at 12%. Previous romantic partners were named by 10% of those who have been harassed, and co-workers were identified by 7%.

Most internet users do not know who is responsible for their online harassment

Among those who have experienced harassment online, the % who said their most recent experience involved the following types of people

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=931. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Men who have experienced harassment were more likely than women to say their most recent incident involved a stranger, 44% vs. 32%. Similarly, 33% of men said they didn’t know the identity of the person involved, compared with 20% of women. This may be tied to the nature of the environments in which men report experiencing online harassment. Both gaming and the comments section of a website are places where identifying yourself is not a requirement for participation. In other words, both environments largely operate on anonymity.

Some 27% of women who have experienced online harassment said their most recent incident involved an acquaintance, somewhat higher than the 20% of men who said the same. Women were also more likely to say a family member was involved, 16% vs. 8% of men. Again, this may reflect the environments in which women are most likely to experience harassment: Social media activity is built around strong ties (family) and loose ties (acquaintances), and some platforms require people to participate with their real name.

Young people, those ages 18-29, who have experienced online harassment were more likely than any other age group to say their most recent incident involved a friend. Almost three-in-ten, 29%, said so. This is unsurprising considering how much of young people’s social lives plays out online. They were also more likely than those 50 or older to cite an acquaintance, 29% vs. 17%.

Open-end responses: Who are harassers?

In comments where the person responsible was discussed, “family drama” was frequently noted.

“A family member unhappy with my decisions is threatening my family.”

“Adult son making rude comments because he feels he is being treated unfairly. Jealously, senseless!”

“It was a situation between my sister and I…we had a verbal altercation because of decisions she made and she took to Facebook to call me all kinds of names.”

“The family of my late husband posted things to me – hurtful things. Eventually they stopped when I ignored them and blocked them.”

Ex-romantic partners were also a recurring issue.

“I was being stalked by an ex and had to report it to the police.”

“Internet stalking (checking up on me) that led to staking in real life by an ex.”

“An Ex-gf who was really upset with our break-up chose to post offensive things about me online in a number of places.”

“I have been experiencing frustration with a former girlfriend of my boyfriend’s stalking me. She has been able to locate where I work, my email address, personal cell phone number. She sends text messages on a weekly basis and threatens me.”

“I had a former partner continually trying to contact me after I broke things off. When he couldn’t reach me, he started having friends message. Eventually I changed my information and converted all my posts to private.”

“Husband’s ex-wife stalked and stole my identity.”

Part 3: Responses to Online Harassment

Ignoring vs. responding to harassment

60% of those who have experienced harassment ignored their most recent incident while 40% responded to it. Among those who either ignored or responded to their most recent experience with online harassment, the % who felt it was effective vs. not effective ...

Source: American Trends Panel (wave 4) Survey conducted May 30-June 30, 2014 n=549 for those who ignored harassment, n=368 for those who responded to harassment. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

People who experience online harassment employ a variety of tactics in response. Some simply ignore the behavior. Others respond directly on the platform, or notify website administrators. Some employ offline methods and involve law enforcement. Whichever option is chosen, the large majority of people are satisfied with the outcome.

When asked to think of their most recent incident, 60% of those who have experienced online harassment said that they elected to ignore the behavior. When asked if they felt ignoring it was effective at making the situation better, 83% answered affirmatively and 17% were not satisfied.

Open-end responses: Ignoring harassment

A portion of respondents in the open-end comments brushed off online harassment as “nothing too major” and often chose to ignore it.

“I just didn’t let it bother me.”

“Nah, I do not generally care about what people say online, as it has nothing to do with real life.”

“Just laugh at them and call them ‘MORONS’……..”

“Too much to relate really: It is a general characteristic of the medium and environs – hence I visit sparingly and do not comment or interact online if I can help it. It feels like bottom-feeders are the norm online, in my experience.”

“Same person kept harassing me on a Facebook group for an extended period of time. Threatening me, calling me names, etc…But I know the person is just some random “troll” (you need to know what that means on the internet) and I didn’t take it seriously. Online harassment does not faze me. People should learn not to get offended by silly things.”

Response Steps

Actions in response to online harassment ranged from direct confrontation online to involving law enforcement.

Some 40% of those who have experienced online harassment took some sort of action in response to their most recent incident, ranging from direct confrontation to engagement with law enforcement.

When asked if they felt that any of the steps they took were effective at making their most recent situation better, three-quarters of those who responded to online harassment said they did. A quarter were still not satisfied.

Overall:

47% of those who responded to their most recent incident with online harassment confronted the person online responsible for the harassment

44% unfriended or blocked the person responsible

22% reported the person responsible to the website or online service

18% discussed the problem online to draw support for themselves

13% changed their username or deleted their profile

10% withdrew from an online forum

8% stopped attending certain offline events or places

5% reported the problem to law enforcement

There were few demographic differences between those who took various steps in response to their online harassment, with two key exceptions: women and those under 50 who responded to their harassment were more likely than their counterparts to unfriend or block the perpetrator. Some 55% of women did so, compared with 34% of men and 49% of those under 50 unfriended or blocked someone, compared with 27% of those over 50.

For some, responding to harassment is a relatively straightforward affair. Forty-nine percent of those who responded to their recent harassment incident took a single step. But others engaged in a more multi-faceted response, as 48% took multiple actions in response to their most recent experience. Indeed, some 8% of online harassment victims report taking four or more of these specific actions.

As noted in Part 1, online harassment exists along a spectrum of severity. Of those who have been harassed online, some 45% have experienced especially severe forms of harassment (these include physical threats, sexual harassment, stalking, or harassment over a sustained period of time). They tend to have a much different response to their most recent harassment incident compared with the 55% of harassment victims who have only experienced less severe versions of these behaviors (i.e., name-calling and embarrassment).

Specifically, past victims of more severe forms of harassment were more likely to respond to their most recent incident [5] by unfriending or blocking the person responsible (62% vs. 27%), confronting the person responsible online (53% vs. 41%), reporting the person responsible to the website or online service (34% vs. 11%), changing their username or deleting their profile (21% vs. 4%), or ending their attendance at certain offline events or places (12% vs. 3%). They were also more likely to take multiple actions in response to their most recent incident (67% vs. 30%).

Open-end responses: Response steps

Besides the response steps listed, a number of respondents in the comments reported that they confronted the person face-to-face. Others brought the problem to the attention of other authority figures, like lawyers or managers at work.

“Confronted the person face-to-face.”

“Called the person.”

“Talked out the problem.”

Confronted the person offline politely.”

“Secured a lawyer.”

“Got a lawyer.”

“Reported it to a supervisor at work.”

“Confronted at work and eventually terminated.”