The Warning in Gary Webb’s Death

by Robert Parry

December 9, 2011

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

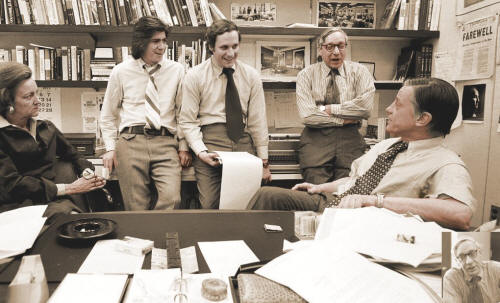

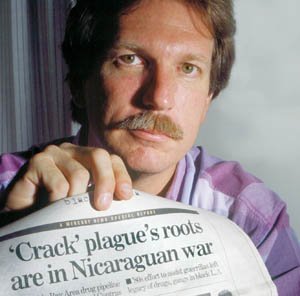

Journalist Gary Webb holding a copy of his Contra-cocaine article in the San Jose Mercury-News.

Every year since investigative journalist Gary Webb took his own life in 2004, I have marked the anniversary of that sad event by recalling the debt that American history owes to Webb for his brave reporting, which revived the Contra-cocaine scandal in 1996 and forced important admissions out of the Central Intelligence Agency two years later.

But Webb’s suicide on the evening of Dec. 9, 2004, was also a tragic end for one man whose livelihood and reputation were destroyed by a phalanx of major newspapers the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times serving as protectors of a corrupt power structure rather than as sources of honest information.

In reviewing the story again this year, I was struck by how Webb’s Contra-cocaine experience was, in many ways, a precursor to the subsequent tragedy of the Iraq War.

In the 1980s, the CIA’s analytical division was already showing signs of politicization, especially regarding President Ronald Reagan’s beloved Contras and their war against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government and the U.S. press corps was already bending to the propaganda pressures of a right-wing Republican administration.

Looking back at CIA cables from the early-to-mid-1980s, you can already see the bias dripping from the analytical reports. Any drug accusation against the leftist Sandinistas was accepted without skepticism and usually with strong exaggeration, while the opposite occurred with evidence of Contra cocaine smuggling; then there was endless quibbling and smearing of sources.

So, to put these reports in anything close to an accurate focus, you would need special lenses to correct for all the politicized distortions. Yet, the U.S. news media, which itself was under intense pressure not to appear “liberal,” worsened the Reagan administration’s fun-house reflection of reality and attacked any dissident journalist who wouldn’t go along.

Thus, Americans heard a lot about how the evil Sandinistas were trying to “poison” America’s youth with cocaine, although there was not a single interception of a drug shipment from Nicaragua during the Sandinista reign, except for one planeload of cocaine that the United States flew into and out of Nicaragua in a clumsy “sting” operation.

On the other hand, substantial evidence of Contra-related cocaine shipments out of Costa Rica and Honduras was kept from the American people with Reagan’s Justice Department and CIA intervening to head off investigations and thus prevent embarrassing disclosures. The chief role of the big newspapers in this upside-down world was to heap ridicule on anyone who told the truth.

During that time frame of the early-to-mid-1980s, the patterns were set for CIA analysts to advance their careers (by giving the president what he wanted) and mainstream journalists to protect theirs (by accepting propaganda). By 2002-2003, these patterns had become deeply engrained, leaving almost no one to protect the American people from a new round of falsehoods aimed at Iraq.

Though I was not in touch with Webb in the last months of his life in 2004, I have always wondered if he saw this connection between his own valiant efforts to correct the historical record about Contra-cocaine trafficking in 1996 and the victory of lies over truth regarding Iraq’s WMD in 2002-2003.

In the weeks before Webb’s suicide, there also was the intervening fact of George W. Bush’s reelection and with it, the dashed expectation that the CIA analysts and the mainstream journalists who played along with the Iraq-WMD fabrications might face some serious accountability. At the moment when Webb picked up his father’s pistol and put it to his head, there must have appeared little hope that anything would change.

Indeed, we are now seeing yet another replay of this systematic distortion of information, this time regarding Iran and its alleged nuclear weapons program. Any tidbit of information against Iran is exaggerated, while exculpatory data is downplayed or ignored.

So, it may be timely again to recount what happened to Gary Webb and to reflect on the dangers of allowing this corrupt disinformation system to press ahead unchecked.

Dark Alliance

For me, the tragic story of Gary Webb began in 1996 when he was working on his “Dark Alliance” series for the San Jose Mercury News. He called me at my home in Arlington, Virginia, because, in 1985, I and my Associated Press colleague Brian Barger had been the first journalists to reveal the scandal of Reagan’s Nicaraguan Contras funding themselves in part by collaborating with drug traffickers.

Webb explained that he had come across evidence that one Contra-connected drug conduit had funneled cocaine into Los Angeles, where it helped fuel the early crack epidemic. Unlike our AP stories a decade earlier, which focused on the Contras helping to ship cocaine from Central America into the United States, Webb said his series would examine what happened to the Contra cocaine after it reached the streets of Los Angeles and other cities.

Besides asking about my recollections of the Contras and their cocaine smuggling, Webb wanted to know why the scandal never gained any real traction in the U.S. national news media. I explained that the ugly facts of the drug trafficking ran up against a determined U.S government campaign to protect the Contras’ image. In the face of that resistance, I said, the major publications, the likes of the New York Times and the Washington Post, had chosen to attack the revelations and those behind them rather than to dig up more evidence.

Webb sounded confused by my account, as if I were telling him something that was foreign to his personal experience, something that just didn’t compute. I had a sense of his unstated questions: Why would the prestige newspapers of American journalism behave that way? Why wouldn’t they jump all over a story that important and that sexy, about the CIA working with drug traffickers?

I took a deep breath, sensing that he had no idea of the personal danger he was about to confront. Well, he would have to learn that for himself, I thought. It surely wasn’t my place to warn a journalist away from a significant story just because it carried risks.

So, I simply asked Webb if he had the strong support of his editors. He assured me that he did. I said their backing would be crucial once his story was out. He sounded perplexed, again, as if he didn’t know what to make of my cautionary tone. I wished him the best of luck, thinking that he would need it.

The Safe Route

When I hung up, I wasn’t sure that the Mercury News would really press ahead with the story, considering how the big national news outlets had dismissed and ridiculed the notion that President Reagan’s beloved Contras had included a large number of drug traffickers.

It never seemed to matter how much evidence there was. It was much easier, and safer, career-wise, for Washington journalists to reject incriminating testimony against the Contras, especially when it came from other drug traffickers and from disgruntled Contras. Even U.S. law-enforcement officials who discovered evidence were disparaged as overzealous and congressional investigators were painted as partisan.

In 1985, as we were preparing our first AP story on this topic, Barger and I knew that the evidence of Contra-cocaine involvement was overwhelming. We had a broad range of sources both inside the Contra movement and within the U.S. government, people with no apparent ax to grind who had described the cocaine-smuggling problem.

One source was a field agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); another was a senior official on Reagan’s National Security Council (NSC) who told me that he had read a CIA report about how a Contra unit based in Costa Rica had used cocaine profits to buy a helicopter.

However, after our AP story was published in December 1985, we came under attack from the right-wing Washington Times. That was followed by dismissive stories in the New York Times and the Washington Post. The notion that the Contras, whom President Reagan had likened to America’s Founding Fathers, could be implicated in the drug trade was simply unthinkable.

Yet, it was always odd to me that many of the same newspapers had no problem accepting the fact that the CIA-backed Afghan mujahedeen were involved in the heroin trade, but bristled at the thought that the CIA-backed Nicaraguan Contras might be cut from the same cloth.

A key difference, which I learned both from personal experience and from documents that surfaced during the Iran-Contra scandal, was that Reagan had assigned a young group of ambitious intellectuals such as Elliott Abrams and Robert Kagan to oversee the Contra war.

These neoconservatives worked with old-line anticommunists from the Cuban-American community, such as Otto Reich, and CIA propagandists, such as Walter Raymond Jr., to aggressively protect the Contras’ image. And the Contras were always on the edge between getting congressional funding or having it cut off.

So, that combination, the propaganda skills of Reagan’s Contra-support team and the fragile consensus for continuing Reagan’s pet Contra war, meant that any negative publicity about the Contras would be met with a fierce counterattack.

Going to Editors

The neoconservatives were also bright, well-schooled, and skilled in their manipulation of language and information, a process they privately called “perception management.” They proved adept, too, at ingratiating themselves with senior editors at major news outlets.

By the mid-1980s, these patterns had become well-worn in Washington. If a journalist dug up a story that put the Contras in a negative light, he or she could expect the Reagan administration’s propaganda team to make contact with a senior editor or bureau chief and lodge a complaint, apply some pressure, and often offer up some dirt about the offending journalist.

Also, many news executives in that time frame were sympathetic toward Reagan’s hard-line foreign policy, especially after the humiliations of the Vietnam War and the Iranian revolution. Supporting U.S. initiatives abroad, or at least not allowing your reporters to undercut those policies, was seen as patriotic.

At the New York Times, executive editor Abe Rosenthal was one of the news media’s most influential neoconservatives, declaring that he was determined to steer the newspaper back to “the center,” by which he meant to the right.

At AP, general manager Keith Fuller was known to be a strong Reagan supporter and his preferences were sometimes expressed forcefully to AP’s Washington bureau where I worked. At the Washington Post and Newsweek (where I went to work in 1987), there was also a strong sense that Reagan-era scandals should not reach the president, that it would not be “good for the country.”

In other words, on the issue of Contra drug trafficking, there was a confluence of interests between the Reagan administration, which was determined to protect the Contras’ public image, and senior news executives, who wanted to adopt a “patriotic” posture after convincing themselves that the country shouldn’t endure another wrenching battle over wrongdoing by a Republican president.

The popular image of courageous editors standing up for their reporters in the face of government pressure was not the reality, especially not where the Contras were concerned.

Reverse Rewards

So, instead of a process that outsiders might imagine, where journalists who dug out tough stories got rewarded, the actual system worked in the opposite way. The careerists in the news business quickly grasped that the smart play when it came to the Contras was either to be a booster or at least to pooh-pooh evidence of the Contras’ brutality or drug traffickers.

The same rules applied to congressional investigators. Anyone who pried into the dark corners of the Nicaraguan Contra war faced ridicule, as happened to Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts when he followed up the early AP stories with a courageous investigation that discovered more ties between cocaine traffickers and the Contras.

When his Contra-cocaine report was released in 1989, its findings were greeted with yawns and smirks. News articles were buried deep inside the major newspapers and the stories focused more on alleged flaws in his investigation than on his revelations.

For his hard work, Newsweek summed up the prevailing “conventional wisdom” on Kerry by calling him a “randy conspiracy buff.” Being associated with breaking the Contra-cocaine story was also regarded as a black mark on my own career.

To function in this upside-down world, where reality and perception often clashed and perception usually won, the big news outlets developed a kind of cognitive dissonance that could accept two contradictory positions.

On one level, the news outlets did accept the undeniable reality that some of the Contras and their backers, including the likes of Panamanian General Manuel Noriega, were implicated in the drug trade, but then simultaneously treated this reality as a conspiracy theory.

Squaring the Circle

The Square within the Circle [is one of] the most potent of all the magical figures. --The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy, by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky

***

"As the sky with its stars and constellations is nothing separate from the All but includes the All, so is the 'firmament' of Man not separate from Man; and as the Universal Mind is not ruled by any external being, likewise the firmament in Man (his individual sphere of mind) is not subject to the rule of any creature, but is an independent and powerful whole." -- This fundamental truth of occultism is allegorically represented in the interlaced double triangles. He who has succeeded in bringing his individual mind in exact harmony with the Universal Mind has succeeded in reuniting the inner sphere with the outer one, from which he has only become separated by mistaking illusions for truths. He who has succeeded in carrying out practically the meaning of this symbol has become one with the father; he is virtually an adept, because he has succeeded in squaring the circle and circling the square. All of this proves that Paracelsus has brought the root of his occult ideas from the East. -- The Life of Philippus Theophrastus Bombast of Hohenheim Known by the Name of Paracelsus and the Substance of his Teachings, by Franz Hartmann, M.D.

***

Our scientific procedure is obviously the negation of the Absolute. That was an acute and happy remark of Goethe's: "He who devotes himself to nature attempts to find the squaring of the circle."-- The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, by Houston Stewart Chamberlain

***

The geometrician does not know the square of the circle. -- De Monarchia of Dante Alighieri

***

It is impossible to square the circle perfectly because of its arc. -- The Convivio, by Dante Alighieri

***

Arnesen proclaimed in a firm voice that all of the challenges in aquaculture would be mastered, including the biggest one of all: how to convert salmon to vegetarianism? The carnivorous predator fish need large amounts of animal protein. The feed concentrate dumped into the cages by the ton is made mainly of fishmeal and fish oil. It's a negative cycle: 4-6 kilograms of wild fish are killed and made into meal to produce one kilo of salmon flesh. More than half of the world's fish catch now goes to making feed concentrate for salmon and other animals. Farm-bred salmon consume more animal protein than they produce. How can that be sustainable? "We see the problem the same way the WWF does," conceded Petter Arnesen. "We're experimenting with increasing the share of vegetable protein in the feed, using soy, for example." The company was determined to achieve this, he said, as the fish reserves of the world's oceans were already "exhausted". The trouble is, when there is too little fish product in the feed the salmon raised on it no longer contain as much healthy omega 3 fatty acids. That's not the kind of salmon the retailers want. The poor Technical Director has the daunting task of circling the square -- luckily the WWF can lend him a hand: by simply designating the whole thing "sustainable". -- Panda Leaks: The Dark Side of the WWF, by Wilfried Huismann

***

Squaring the Circle in the Creation of Sacred Space

This was how Bridges explained the geometries of the Great Tree to interested students back in 1991. As far as we know, he did not intend it as an explanation of the Hieroglyphic Monad. But if one visualizes this drawing of the Tree in three dimensions, one should see two spheres sharing the same axis, that axis ending at the center of a third sphere, at the center of a cross of four directions. One should see at least two cones.

If one locates where different Sephiroth are located and at the intersection of which curved or planar geometric boundaries, or puzzles over the “location” of different planets, you will indeed have a “Helping Hand” to go back through the geometries of the Hieroglyphic Monad, and proceed on the Theorem XVIII.

-- The Hieroglyphic Monad of John Dee. Theorems I-XVII: A Guide to the Outer Mysteriesm by Teresa Burns and J. Alan Moore

***

Although the CIA knew that the estimated 120,000 VC Self-Defense Forces (which Westmoreland described as "old men, old women and children") were the integral element of the insurgency, Carver, after being shown "evidence that I hadn't heard before," cut a deal on September 13. He sent a cable to Helms saying: "Circle now squared .... We have agreed set of figures Westmoreland endorsed." [14] In November National Security Adviser Walt Rostow showed President Johnson a chart indicating that enemy strength had dropped from 285,000 in late 1966 to 242,000 in late 1967. President Johnson got the success he wanted to show, and Vietnam got Tet.

-- The Phoenix Program, by Douglas Valentine

Only occasionally did a major news outlet seek to square this circle, such as during Noriega’s drug-trafficking trial in 1991 when U.S. prosecutors called as a witness Colombian Medellin cartel kingpin Carlos Lehder, who, along with implicating Noriega, testified that the cartel had given $10 million to the Contras, an allegation first unearthed by Sen. Kerry.

“The Kerry hearings didn’t get the attention they deserved at the time,” a Washington Post editorial on Nov. 27, 1991, acknowledged. “The Noriega trial brings this sordid aspect of the Nicaraguan engagement to fresh public attention.”

However, the Post offered its readers no explanation for why Kerry’s hearings had been largely ignored, with the Post itself a leading culprit in this journalistic misfeasance. Nor did the Post and the other leading newspapers use the opening created by the Noriega trial to do anything to rectify their past neglect.

And, everything quickly returned to the status quo in which the desired perception of the noble Contras trumped the clear reality of their criminal activities.

So, from 1991 until 1996, the Contra-cocaine scandal remained a disturbing story not just about the skewed moral compass of the Reagan administration but also about how the U.S. news media had lost its way.

The scandal was a dirty secret that was best kept out of public view and away from a thorough discussion. After all, the journalistic careerists who had played along with the U.S. government’s Contra defenders had advanced inside their media corporations. As good team players, they had moved up to be bureau chiefs and other news executives. They had no interest in revisiting one of the big stories that they had downplayed as a prerequisite for their success.

Pariahs

Meanwhile, those journalists who had exposed these national security crimes mostly saw their careers sink or at best slide sideways. We were regarded as “pariahs” in our profession. We were “conspiracy theorists,” even though our journalism had proven to be correct again and again.

The Post’s admission that the Contra-cocaine scandal “didn’t get the attention it deserved” didn’t lead to any soul-searching inside the U.S. news media, nor did it result in any rehabilitation of the careers of the reporters who had tried to put a spotlight on this especially vile secret.

As for me, after losing battle after battle with my Newsweek editors (who despised the Iran-Contra scandal that I had worked so hard to expose), I departed the magazine in June 1990 to write a book (called Fooling America) about the decline of the Washington press corps and the parallel rise of the new generation of government propagandists.

I was also hired by PBS Frontline to investigate whether there had been a prequel to the Iran-Contra scandal, whether those arms-for-hostage deals in the mid-1980s had been preceded by contacts between Reagan’s 1980 campaign staff and Iran, which was then holding 52 Americans hostage and essentially destroying Jimmy Carter’s reelection hopes. [For more on that topic, see Robert Parry’s Secrecy & Privilege and America’s Stolen Narrative.]

Then, in 1995, frustrated by the pervasive triviality that had come to define American journalism, and acting on the advice of and with the assistance of my oldest son Sam, I turned to a new medium and launched the Internet’s first investigative news magazine, known as Consortiumnews.com. The Web site became a way for me to put out well-reported stories that my former mainstream colleagues seemed determined to ignore or mock.

So, when Gary Webb called me that day in 1996, I knew that he was charging into some dangerous journalistic terrain, though he thought he was simply pursuing a great story. After his call, it struck me that perhaps the only way for the Contra-cocaine story to ever get the attention that it deserved was for someone outside the Washington media culture to do the work.

When Webb’s “Dark Alliance” series finally appeared in late August 1996, it initially drew little attention. The major national news outlets applied their usual studied indifference to a topic that they had already judged unworthy of serious attention.

It was also clear that the media careerists who had climbed up their corporate ladders by accepting the conventional wisdom that the Contra-cocaine story was a conspiracy theory weren’t about to look back down and admit that they had contributed to a major journalistic failure to inform and protect the American public.

Hard to Ignore

But Webb’s story proved hard to ignore. First, unlike the work that Barger and I did for AP in the mid-1980s, Webb’s series wasn’t just a story about drug traffickers in Central America and their protectors in Washington. It was about the on-the-ground consequences, inside the United States, of that drug trafficking, how the lives of Americans were blighted and destroyed as the collateral damage of a U.S. foreign policy initiative.

In other words, there were real-life American victims, and they were concentrated in African-American communities. That meant the ever-sensitive issue of race had been injected into the controversy. Anger from black communities spread quickly to the Congressional Black Caucus, which started demanding answers.

Secondly, the San Jose Mercury News, which was the local newspaper for Silicon Valley, had posted documents and audio on its state-of-the-art Internet site. That way, readers could examine much of the documentary support for the series.

It also meant that the traditional “gatekeeper” role of the major newspapers, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times, was under assault. If a regional paper like the Mercury News could finance a major journalistic investigation like this one, and circumvent the judgments of the editorial boards at the Big Three, then there might be a tectonic shift in the power relations of the U.S. news media. There could be a breakdown of the established order.

This combination of factors led to the next phase of the Contra-cocaine battle: the “get-Gary-Webb” counterattack. The first major shot against Webb and his “Dark Alliance” series did not come from the Big Three but from the rapidly expanding right-wing news media, which was in no mood to accept the notion that some of President Reagan’s beloved Contras were drug traffickers. That would have cast a shadow over the Reagan Legacy, which the Right was elevating to mythic status.

It fell to Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s right-wing Washington Times to begin the anti-Webb vendetta. Moon, a South Korean theocrat who fancied himself the new Messiah, had founded his newspaper in 1982 partly to protect Ronald Reagan’s political flanks and partly to ensure that he had powerful friends in high places. In the mid-1980s, the Washington Times went so far as to raise money to assist Reagan’s Contra “freedom fighters.”

Self-Interested Testimony

To refute Webb’s three-part series, the Washington Times turned to some ex-CIA officials, who had participated in the Contra war, and quoted them denying the story. Soon, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times were lining up behind the Washington Times to trash Webb and his story.

On Oct. 4, 1996, the Washington Post published a front-page article knocking down Webb’s series, although acknowledging that some Contra operatives did help the cocaine cartels.

The Post’s approach was twofold, fitting with the national media’s cognitive dissonance on the topic of Contra cocaine: first, the Post presented the Contra-cocaine allegations as old news, “even CIA personnel testified to Congress they knew that those covert operations involved drug traffickers,” the Post sniffed, and second, the Post minimized the importance of the one Contra smuggling channel that Webb had highlighted in his series, saying that it had not “played a major role in the emergence of crack.”

A Post sidebar story dismissed African-Americans as prone to “conspiracy fears.”

Next, the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times weighed in with lengthy articles castigating Webb and “Dark Alliance.” The big newspapers made much of the CIA’s internal reviews in 1987 and 1988, almost a decade earlier, that supposedly had cleared the spy agency of any role in Contra-cocaine smuggling.

But the CIA’s cover-up began to weaken on Oct. 24, 1996, when CIA Inspector General Frederick Hitz conceded before the Senate Intelligence Committee that the first CIA probe had lasted only 12 days, and the second only three days. He promised a more thorough review.

Mocking Webb

Webb, however, had already crossed over from being a serious journalist to a target of ridicule. Influential Post media critic Howard Kurtz mocked Webb for saying in a book proposal that he would explore the possibility that the Contra war was primarily a business to its participants. “Oliver Stone, check your voice mail,” Kurtz chortled.

However, Webb’s suspicion was no conspiracy theory. Indeed, White House aide Oliver North’s chief Contra emissary, Robert Owen, had made the same point in a March 17, 1986, message about the Contras leadership. “Few of the so-called leaders of the movement . . . really care about the boys in the field,” Owen wrote. “THIS WAR HAS BECOME A BUSINESS TO MANY OF THEM.” [Emphasis in original.]

In other words, Webb was right and Kurtz was wrong, even Oliver North’s emissary had reported that many Contra leaders treated the conflict as “a business.” But accuracy had ceased to be relevant in the media’s hazing of Gary Webb.

In another double standard, while Webb was held to the strictest standards of journalism, it was entirely all right for Kurtz, the supposed arbiter of journalistic integrity who was also featured on CNN’s Reliable Sources, to make judgments based on ignorance. Kurtz would face no repercussions for mocking a fellow journalist who was factually correct.

The Big Three’s assault, combined with their disparaging tone, had a predictable effect on the executives of the Mercury News. As it turned out, Webb’s confidence in his editors had been misplaced. By early 1997, executive editor Jerry Ceppos, who had his own corporate career to worry about, was in retreat.

On May 11, 1997, Ceppos published a front-page column saying the series “fell short of my standards.” He criticized the stories because they “strongly implied CIA knowledge” of Contra connections to U.S. drug dealers who were manufacturing crack cocaine. “We did not have enough proof that top CIA officials knew of the relationship,” Ceppos wrote.

Ceppos was wrong about the proof, of course. At AP, before we published our first Contra-cocaine article in 1985, Barger and I had known that the CIA and Reagan’s White House were aware of the Contra-cocaine problem.

However, Ceppos had recognized that he and his newspaper were facing a credibility crisis brought on by the harsh consensus delivered by the Big Three, a judgment that had quickly solidified into conventional wisdom throughout the major news media and inside Knight-Ridder, Inc., which owned the Mercury News. The only career-saving move career-saving for Ceppos even if career-destroying for Webb was to jettison Webb and his journalism.

A ‘Vindication’

The big newspapers and the Contras’ defenders celebrated Ceppos’s retreat as vindication of their own dismissal of the Contra-cocaine stories. In particular, Kurtz seemed proud that his demeaning of Webb now had the endorsement of Webb’s editor.

Ceppos next pulled the plug on the Mercury News’ continuing Contra-cocaine investigation and reassigned Webb to a small office in Cupertino, California, far from his family. Webb resigned from the paper in disgrace.

For undercutting Webb and other Mercury News reporters working on the Contra-cocaine investigation, Ceppos was lauded by the American Journalism Review and was given the 1997 national Ethics in Journalism Award by the Society of Professional Journalists.

While Ceppos won raves, Webb watched his career collapse and his marriage break up. Still, Gary Webb had set in motion internal government investigations that would bring to the surface long-hidden facts about how the Reagan administration had conducted the Contra war.

The CIA published the first part of Inspector General Hitz’s findings on Jan. 29, 1998. Though the CIA’s press release for the report criticized Webb and defended the CIA, Hitz’s Volume One admitted that not only were many of Webb’s allegations true but that he actually understated the seriousness of the Contra-drug crimes and the CIA’s knowledge of them.

Hitz conceded that cocaine smugglers played a significant early role in the Contra movement and that the CIA intervened to block an image-threatening 1984 federal investigation into a San Francisco-based drug ring with suspected ties to the Contras, the so-called “Frogman Case.”

After Volume One was released, I called Webb (whom I had met personally since his series was published). I chided him for indeed getting the story “wrong.” He had understated how serious the problem of Contra-cocaine trafficking had been.

It was a form of gallows humor for the two of us, since nothing had changed in the way the major newspapers treated the Contra-cocaine issue. They focused only on the press release that continued to attack Webb, while ignoring the incriminating information that could be found in the body of the report. All I could do was highlight those admissions at Consortiumnews.com, which sadly had a much, much smaller readership than the Big Three.