Part 2 of 2

6.6 Misuse #6: Mail On CTSS Developed In 1960's Was “Email”The statement:

“Electronic mail, or email, was introduced at MIT in 1965 and was widely discussed in the press during the 1970s. Tens of thousands of users were swapping messages by 1980.” (Crisman et al., 2012)

misuses the term “email” since the reference to

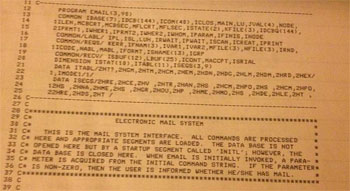

CTSS MAIL, the method referenced and attributed to MIT, was an early text messaging system, not a version of email --- the system of interlocking parts which is the full-scale emulation of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system. This invention refers to the MAIL command on MIT’s CTSS timesharing system. The basic usage of MAIL, as documented in CTSS Programming Staff Note # 39 (Crisman et al., 2012), is below:

The MAIL Command

A new command should be written to allow a user to send a private message to another user which may be delivered at the receiver's convenience. This will be useful for the system to notify a user that some or all of his files have been backed-up. It will also be useful for users to send authors any criticisms.

MAIL LETTER FILE USER1 USER2 USER3 .... MAIL 'ME'

LETTER FILE is the name of a BCD file which contains the message to be sent.

USERn is the designation of the user who is to receive the message. USERn may be a programmer's name or programmer number or the problem-programmer number. It may also be just the problem number if the message is to go to all users of the same problem number.

MAIL ME is the command given by the receiver when he wants the mail to be printed. The files will be left in permanent mode and should be deleted by the receiver at his convenience.

The MAIL command will create or append to the front of a file called MAIL BOX. System messages to the user will be placed in a file called URGENT MAIL. The LOGIN command will notify the user if he has either kind of mail. MAIL ME will always print URGENT MAIL before MAIL BOX.

This invention, MAIL, was not a system of interlocked parts emulating the interoffice, inter-organizational paper mail system. MAIL allowed a CTSS user to transmit a file, written in a third-party editor, and encoded in binary-decimal format (BCD), to other CTSS users.

The delivered message would be appended to the front of a file in the recipient’s directory that represented the aggregate of all received messages. This flatfile message storage placed strict constraints on the capacity of MAIL, and required users to traverse and review all messages one-by-one; search and sort mechanisms were not available. Corruption to the MAIL BOX file could result in the loss of a user’s messages. From the CTSS Programmer’s Guide, Section AH.9.05, (Crisman, 1965):

BOX'. Because of the appending feature of the MAILing process, the command 'DELETE MAIL BOX' should be issued after a message has been PRINTed, to avoid having to run through previous messages to get to the latest one.)

The design choices in MAIL—lack of search and sort facilities, need for an external editor, dependence on CTSS-specific user IDs, and flat-file message storage— put strict constraints on the use and capacity of the command. This was not email --- the system of interlocking parts, created to emulate the interoffice, interorganizational paper-based mail system.

MAIL was well-suited to the low-volume transmission of informal (i.e. unformatted) messages, at best, like text messaging of today.The creator of MAIL admitted this fact:

“The proposed uses [of MAIL],” wrote Tom Van Vleck, “were communication from ‘the system’ to users, informing them that files had been backed up, communication to the authors of commands with criticisms, and communication from command authors to the CTSS manual editor.” (Crisman, 1965)

The limited feature set of MAIL would be carried over to its progeny (SNDMSG, MSG, HERMES), creating headaches for even the most sophisticated technical staffers (Vallee, 1984):In systems like SEND MESSAGE and its successors, such as HERMES, ON-TYME, and COMET, there is no provision for immediate response. A message is sent into a mailbox for later access by the recipient. No automatic filing is provided: Any searching of message files requires users to write their own search programs, and to flag those messages they want to retain or erase. The burden is placed on users to manage their own files, and a fairly detailed understanding of programming and file structures is required. Both senders and receivers must learn about 20 commands, and if they misuse them they can jeopardize the entire data structure. Some messages may even be lost in the process. These drawbacks are compensated for by the fact that the cost per message is very low.

Those who promoted MAIL as "email," when the term "email" did not even exist in 1965, are misusing the term "email" to refer to a command-driven program that transferred BCD-encoded text files, written in an external editor, among timesharing system users, to be reviewed serially in a flat-file.

One would be hard-pressed to draw a historical straight line from MAIL to today’s email systems. MAIL was not "email,” but a text messaging command line system, at best, and perhaps the predecessor to early forms of online discussion boards.6.7 Misuse #7: In 2012, the Term “Email” Now Needs To Be DefinedThis statement (made following news of Ayyadurai's invention of email in 2012, after the Smithsonian’s acquisition of Ayyadurai’s work):

“… we need a more specific definition that captures the essence of computer based electronic mail as it actually emerged. Here is one that was developed in discussion with email pioneers Ray Tomlinson, Tom Van Vleck and Dave Crocker:

‘Electronic mail is a service provided by computer programs to send unstructured textual messages of about the same length as paper letters from the account of one user to recipients' personal electronic mailboxes, where they are stored for later retrieval.’ ” (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012)

serves to misuse and confuse the term email --- the system of interlocking parts which is the full-scale emulation of the interoffice, inter-organizational paperbased mail system, since they conflate the term “electronic mail” with “email” by referencing Ray Tomlinson, Tom Van Vleck and David Crocker as “email pioneers.” Neither Tomlinson nor Van Vleck nor Crocker invented email --- the system of interlocking parts intended to emulate the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system, which specifically Crocker had as of December 1977 concluded “impossible” to build.

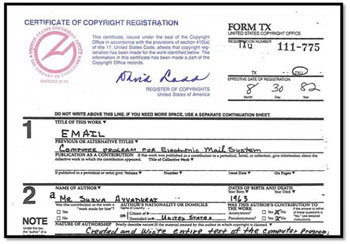

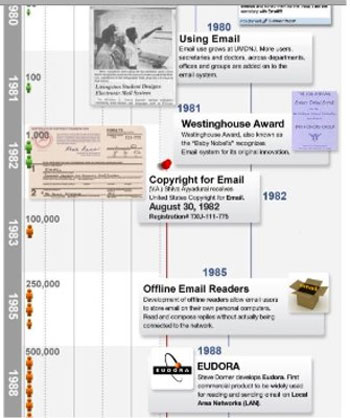

Moreover, this attempt to provide a “specific definition” by Mr. Haigh in 2012, 34 years after email was precisely defined in 1978 by Ayyadurai, as the electronic version of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system, is historical revisionism. Mr. Haigh leads SIGCIS, which is a group of computer “historians” that denies the invention of email in 1978 at UMDNJ, in spite of the clear facts. Their disinformation and historical revisionism is based on equating “electronic messaging” with “email.” These “historians” had already written “email history,” prior to Smithsonian’s acquisition of Ayyadurai’s artifacts on February 16, 2012.The fact is “email” was already clearly defined in 1978 as the electronic interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system, and formally recognized in 1982 by the issuance of the U.S. government’s issuance of the first Copyright for “Email” to Ayyadurai.

Such an attempt to provide a revisionist definition of “email” by industry insiders, in 2012, served one purpose, to allow them: Tomlinson, Van Vleck and Crocker, who worked with the early messaging systems SNDMSG, MAIL and MS, respectively, to retroactively define their work as “email” so as to ensure their primacy to “email,” which they did not create, and had no intention of creating, while misappropriating credit from Ayyadurai.The documentation of that period reveals that the term "email" did not exist prior to 1978. More importantly, the definition of the juxtaposed terms "electronic” and “mail," and a specification of its functions, was anything but clear-cut.

In fact, prior to 1978, the term “electronic mail” and “electronic message” were used interchangeably to refer to the “electronification” of any type of text message, dating back to the telegraph of the 1800s.Email, created by Ayyadurai in 1978, however, has a precise definition as the system of interlocking parts emulating the entire interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system. Prior to Ayyadurai's invention, the confusion about the term “electronic mail” existed:

As Gordon B. Thompson of Bell Northern Research wrote in 1981 (Thompson, 1981):

Electronic Mail Systems give me some major concern. The use of the word "mail" brings with it a lot of baggage, and most certainly people are going to get some surprises because of this. A conventional letter always presents itself to the reader in the same format as it had when it left the writer. In the electronic situation, unless rigid controls are exercised over the terminals allowed on the system, there is no guarantee that the recipient will see the same lay out at all. Designers tell us that the way text is presented can significantly alter the attitude the reader has towards printed text. In electronic mail this variable is left wide open!

Peter Schicker wrote of similar concerns of messaging service and feature lists (Schicker, 1981):

Users of such computer based mail systems are less intrigued by the various internal mechanisms and resource allocation strategies but require exact definitions of the facilities and services that these systems offer. Prospective users, system designers, and service offering companies often compile lists of potential services, e.g., like the list shown in appendix A. Nobody claims that these lists are complete and most often it is admitted freely that these lists represent a first cut synthesis of services offered by other communication facilities (e.g., postal service, telephone, telegraph, telex, etc.).

Unfortunately, these lists mostly convey just a number of buzz-words which everybody interprets in his own fashion. For example, a multitudiness of ...

Even normally well-defined terms like “memo” and “conferencing” took on confusing, often conflicting meanings (Vallee, 1984):

... sary obstacle. Much confusion still exists about the requirements for effective communications. One person calls "conferencing" what another calls "mail."

Or, as James Robinson wrote in the opening lines of his master’s thesis on a review of electronic mail, messaging systems (Robinson, 1983):

'Electronic Mail' is a term that means different things to different people. To one person, electronic mail may represent a technology as old as the telegraph, while to another, it may mean high-powered computers that relay digitized information. Part of the confusion about what electronic mail really is can be traced to how the term is defined. Usually, electronic mail is defined as any process ...

The term “email,” however, has had a clear definition based on Ayyadurai's invention of email, the electronic emulation of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system, which he explicitly named “email.”Therefore, any attempt, in 2012 to redefine it, is clearly an attempt to inappropriately assign “the inventor of email” moniker to those who are not the inventors of email.

6.8 Misuse #8: “Email” Is Not An Invention, But VisiCalc Is An InventionThe statements (in reference to VisiCalc being an invention but email not being an invention since):

“To ‘invent’ something you have to devise some kind of new technology or capability that had not existed before. A computer program is not invented; it is ‘written’ or ‘developed.’ So, for example, it would make sense to say that Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston invented the spreadsheet when they wrote Visicalc. It wouldn’t make sense to say that Google invented the web browser when it developed Google Chrome, as many previous browsers existed, or even that it ‘invented the world’s first Google Chrome’ as that is a specific system rather than a technology.” (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012).

and,

“The system [created by Ayyadurai] will still be of interest to historians as a representative example of a low-budget, small scale electronic mail system constructed from off-the-shelf components, including the HP/1000’s communications, word processing, and database programs.” (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012)

demonstrate ignorance on the fact that “email” is a system just as VisiCalc is a system and is a deliberate attempt to denigrate the significant contribution of Ayyadurai, who invented "email,” the system, which is the electronic version of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system, consisting of the interlocked parts: Inbox, Outbox, Folders, Attachments, etc.

Like VisiCalc, which was an electronic metaphor of the accounting paperbased ledger system, EMAIL, the first email system, also created an electronic metaphor for the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system.

The accessibility of Ayyadurai’s invention of email was its essential attribute. It wasn’t a simple text messaging system inspired to support battlefield communications for soldiers, and usable only by highly trained technical personnel, with cryptic codes and commands. It embodied the definition of “email” as we define the word today. Along these lines, we should remember that Bill Gates, in the early years of Microsoft, stated that the company’s mission was to place a personal computer in every American home. Steven Jobs was determined to make a computer that could be bought in a box just like any other product. Consumers didn’t have to shop for components in various electronics stores. They didn’t have to do anything except plug the machine in and start using it. Microsoft and Apple were defined by the accessibility of their products.

Unquestionably, that was the real innovation on the part of Gates and Jobs. In just the same way, Ayyadurai’s 1978 application, EMAIL, invented email. It created something – a practical, user-friendly electronic communication system on the model of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system – that simply had never existed before, and one which experts of the time had thought “impossible.”

The absurdity of Haigh’s statements, therefore, is simply evidence of the bias of the SIGCIS “historians,” who in collusion with industry insiders, seek to misappropriate credit of Ayyadurai's invention of email. The assertion that email is not an invention, but that VisiCalc is an invention, assumes that the reader will acknowledge such illogic.There is a clear analogy between the invention of EMAIL and the invention of VisiCalc. Bricklin’s title as the Father of the Modern Spreadsheet belies significant contributions to the field of data processing completed prior to the release of VisiCalc. It was the subject of Iveron and Brooks’s seminal Automatic Data Processing and a major research topic for industry and academia.

What Bricklin did was to create an integrated system for data processing, complete with a consistent user interface (UI) and a strong metaphor, which was targeted towards end users. Bricklin’s accomplishment wasn’t that he invented data processing, but that he integrated it and increased accessibility, just as Ayyadurai’s accomplishment wasn’t that he invented electronic messaging, but that he integrated and created a new electronic system for making the paper-based system of interoffice, inter-organizational communications accessible to ordinary office workers.

In the same way that Bricklin’s VisiCalc digitized the system of paper spreadsheets, Ayyadurai’s email digitized the interoffice, inter-organizational paperbased mail system. Both took well-defined social processes, and gave them the power of computation, freeing users from the drudgery of manual recalculation in the former case, or the delivery of physical interoffice memos in the latter case.This puts both projects in stark contrast to the messaging systems of early timesharing architecture, which evolved to address the administrative and technical needs of mainframe users.

As stated in RFC 808, most of these message systems “were not formal projects (in the sense of explicitly sponsored research), but things that ‘just happened,’” and Jacques Vallee wrote of these early systems (Vallee, 1984):

The human factors of communications are still largely ignored. As new companies get into the field, they hire the best programmers they can find to implement message systems. These programmers are often compiler writers or experts in operating systems and have had no experience in dealing with end users. They have operated in a completely different environment, where communications had a much narrower meaning. Some early successes have also had the unfortunate result of freezing the technical reality of the field for too long. Network mail on the ARPANET is a case in point. Introduced in the early 1970s, electronic mail systems have been very successful on the ARPANET, where they served a highly trained community of technical experts. When it came time to design new systems for wider communities, these same technical experts found it very difficult to be creative in ways that differed from what they had first learned.

The statement by the SIGCIS “historian,” part of the industry insider clique, has asserted, with reference to Ayyadurai's work that:

“The system will still be of interest to historians as a representative example of a low-budget, small scale electronic mail system constructed from off-the-shelf components, including the HP/1000’s communications, word processing, and database programs.” (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012).

is simply a false, unscholarly, and denigrating statement.

This statement reveals deliberate and reckless ignorance of the facts, which are accessible now at the Smithsonian.

EMAIL, the first email system, was designed as an integrated system—it included all its own facilities for message handling, distribution, composition, archival, and user management. It was “small scale” only in the sense that it did not need the ARPANET, in contrast to systems like MAIL and MSG, which leveraged a host of facilities in the host environment. EMAIL the program and system, consisted of nearly 50,000 lines of FORTRAN IV code, unlike Van Vleck’s MAIL command, which comprised less than 300 lines of MAD, a high-level language on the CTSS (Crisman et al., 2012).

EMAIL was far from a "small-scale electronic mail system." EMAIL was a full-scale emulation of the entire interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system, with all the features we now experience in modern email programs and many features, which some email programs even in the late 1990's, did not have.What also needs to be investigated, by likely an independent professional ethics body, is the biased, unscholarly, and defamatory attacks on Ayyadurai (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012), and the clear conflict of interest, as exemplified in the list of individuals in Mr. Haigh’s “Acknowledgements” section thanking those who helped him in denigrating Ayyadurai:“Acknowledgements: Thanks to the dozens of people who sent me hundreds of messages after learning that I was working on a response for the Post. Many helped to read and shape earlier drafts. In no particular order: Evan Koblentz, Catherine Lathwell, Peter Meyer, Dave Walden, Debbie Deutsch, Marie Hicks, James Sumner, Ken Pogran, Tom Van Vleck, Dag Spicer, Mark Weber, JoAnne Yates, Murray Turoff, Al Kossow, Ramesh Subramanian, David Alan Grier, Paul McJones, Nathan Ensmenger, David Hemmendinger, Jeffrey Yost, David Moran, Peggy Kidwell, Debbie Douglas, Alex Bochannek, Bill McMillan, Len Shustek, Petri Paju, Elizabeth Finler, Dave Crocker, Ray Tomlinson, Pierre Mounier Kuhn, James P.G. Sterbenz, Ben Barker, Jim Cortada, and Craig Partridge.” (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012)

A significant cluster or coalition of the individuals listed in the Acknowledgements have a direct and indirect, and/or close affiliation to Raytheon/BBN, who claims they “invented email,” as evident on their website (Raytheon/BBN, n.d.), which brandishes the ‘@’ logo with its numerous press and marketing releases claiming that it is the home of the “inventor of email,” Mr. Ray Tomlinson.6.9 Misuse #9: Dec And Wang Created “Email”The statement:

“By 1980, electronic mail systems aimed at the office environments were readily available from companies such as DEC, Wang, and IBM.” (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012)

conflates all forms of electronic communication, from telegraph services, to Telex or CBMS systems with the email --- the system of interlocked parts intended to emulate the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system. This conflation is confusing, and an attempt to equate the broad term “electronic mail,” dating back to the 1800s, with email, the system.The offerings of “electronic mail” systems by private suppliers varied greatly, and were largely incompatible. Wang Laboratories, for example, had already been well established for its line of word processing equipment (Wang Systems Newsletter, 1979). When network facilities became readily available, it bolted on file transfer facilities to its machines, creating a line of “communicating word processors” (Trudell et al., 1984). This

networking of word processors is not email --- the system of interlocked parts intended to emulate the interoffice, interorganizational paper-based mail system.In 1980, there was tremendous pressure to innovate in the “office automation sector.” However, as addressed in James Robinson’s 1983 thesis, “An Overview of Electronic Mail Systems” (Robinson, 1983), these offerings were part of a larger defensive strategy:

“[Computer-based message systems] are sold to users who have an interest in implementing electronic mail on their current equipment. Not surprising therefore, many of the vendors in this grouping tend to be minicomputer manufacturers such as Data General and Prime. The reason for this is not so much that minicomputer manufacturers have a real interest in electronic mail, but rather have devised messaging systems in an attempt to prevent other firms from selling a system that would run on their hardware. Thus, this type of electronic mail system has evolved as part of a defensive strategy by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). An excellent example of a product by an OEM is Wang Laboratories Inc.’s Mailway” (Wang Systems Newsletter, 1979)

The "electronic mail" offerings by private industry in 1980 were not the system of interlocked parts emulating the entire interoffice, inter-organizational paperbased mail system. They were, at best, wildly unstable and inconsistent.6.10 Misuse #10: Laurel Was “Email”The statement:

"...the PARC email software, Laurel, ran on the user’s local computer, was operated with a mouse, and pulled messages from the PARC server to a personal hard drive for storage and filing." (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012)

is a misuse of the term email --- the system of interlocking parts which was the full-scale emulation of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system.

The invention, Laurel, was a mail user interface program for the Xerox Alto. It was a graphical front-end to a series of messaging programs akin to SNDMSG and MS (Schroeder et al., 1984). The use of mouse was an innovation of its host environment Alto, not of Laurel itself (Alto User Handbook, 1979).

Laurel was capable of basic message composition, scanning and flat-file storage (through the use of its *.mail files). Like other file-flat approaches, mail management remained in the hands of users (ALTO World Newsletter, 1979).The Laurel Manual, as it existed at Stanford in September 1980 (Stanford, 1980) provided a thorough explanation of what Laurel was, and what its capabilities were.

Laurel was just a user interface, and not the system of interlocked parts to emulate the entire interoffice paper mail system.Laurel was disconnected and relied on "Piping" other small programs which were loosely connected to each other.

Mention of MSG in the official Laurel documentation refers to the same command program discussed earlier, created and critiqued by John Vittal, and listed in RFC 808 as running on a TENEX operating system. Maxc referred to a Xerox-produced machine that emulated the facilities of PDP-10 TENEX-based systems. Its operation is well documented (Fiala et al., 1974). It follows that

Laurel, as it existed in 1979 and 1980, fundamentally depended on MSG and Maxc, for message transmission. It was an Alto-based front-end for a more pedestrian MSG program. Ironically, the revealing kinship of Laurel and MSG is well described in the 1979 Whole ALTO World Newsletter (ALTO World Newsletter, 1979). The sentence,

“Eventually, the services of Laurel will surpass those of MSG, but at present, the two are roughly equivalent in function,” should not be overlooked.

The “distributed message system” mentioned in the Laurel Manual would eventually be realized in Grapevine, tested on a limited number of clients in 1980, and not publicly documented (‘ACM Transactions on Computer systems’, 1984) until 1982, well after Ayyadurai’s invention of email was well established in a production environment. Larry Tesler, who was at Xerox throughout Laurel’s development, corroborates these points (Tesler, 2012).

A review of period documentation helps to put Laurel in perspective. It was, as of 1979 and 1980, an Alto-based graphical front-end for MSG. It stood on the foundations of the beautifully sophisticated Alto environment, and contributed Alto- specific operations like menu picking and Bravo-type editing, which were not available in other MSG environments.

However,

Laurel 2.0 provided only a small subset of the features available in Ayyadurai’s EMAIL, lacking an attachment editor, relational database, administrator/ postmaster functionality, prioritization and search tools, among others. The Alto was a brilliant machine, the precursor to the Apple machines, and Laurel would evolve to become a worthy Alto application. However, as of 1980, Laurel was not the state-of-the–art technology. Readers are encouraged to read the Laurel Manual for details.

6.11 Misuse #11: The Term “Email” Belongs To CompuserveThe statement:

“For years CompuServe users could type “GO EMAIL’ to read their messages….” (Compuserve Information Service User’s Guide, 1983)

is a misdirection to attempt to convince readers that the term “email” existed prior to the invention of email --- the system of interlocked parts intended to emulate the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system.

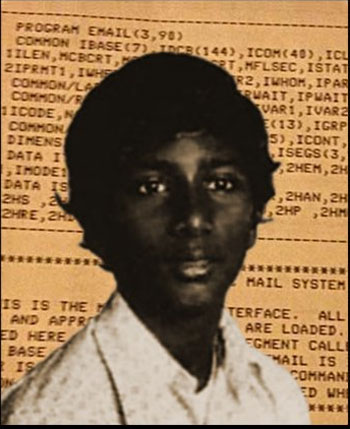

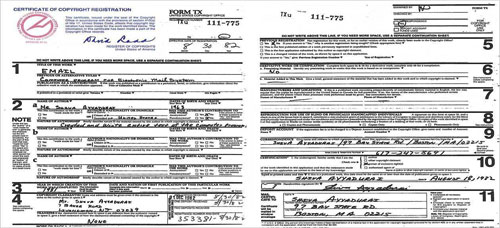

The term “email” was created and coined by V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai in 1978 at UMDNJ. Those five characters E-M-A-I-L were juxtaposed together to name the main subroutine of the first email system. Ayyadurai coined the term email for the idiosyncratic reason that in 1978 FORTRAN IV only allowed for a six-character maximum variable and subroutine naming convention, and the RTE-IV operating system had a five-character limit for program names.

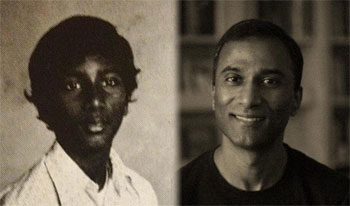

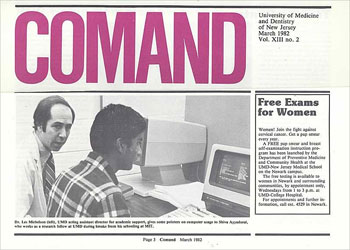

By 1980, Ayyadurai’s email system was in production use at UMDNJ. Needless to say, EMAIL, the program, and its user manual were already in distribution around the UMDNJ campus.

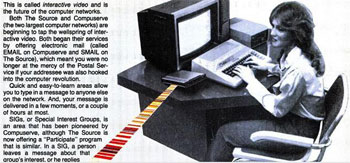

Email was a CompuServe trademark in 1983, but that remains a moot point for discussions of primacy. CompuServe applied for an EMAIL trademark on June 27, 1983, an effort that it abandoned in August 1984, likely because of the prior arte of email dating back to Ayyadurai’s Copyright in 1982. However, for the sake of clarity and transparency, two instances of CompuServe’s 1983 EMAIL advertising are included below:

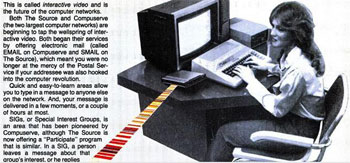

This is called interactive video and is the future of the computer networks.

Both The Source and Compuserve (the two largest computer networks) are beginning to tap the wellspring of interactive video. Both began their services by offering electronic mail (called EMAIL on Compuserve and SMAIL on The Source), which meant you were no longer at the mercy of the Postal Service if your addressee was also hooked into the computer revolution.

Quick and easy-to-learn areas allow you to type in a message to anyone else on the network. And, your message is delivered in a few moments, or a couple of hours at most.

SIGs, or Special Interest Groups, is an area that has been pioneered by Compuserve, although The Source is now offering a "Participate" program that is similar. In a SIG, a person leaves a message about that group's interest, or he replied ...

Fig. 8. Taken from the August, 1983 Edition of Popular Mechanics Magazine, pg. 107.

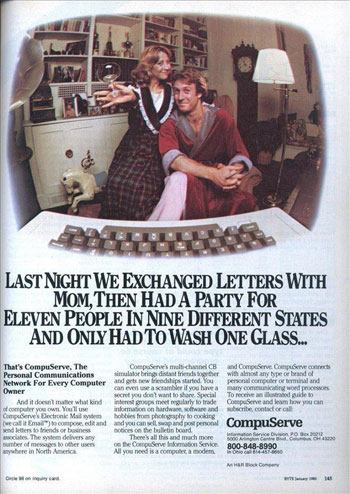

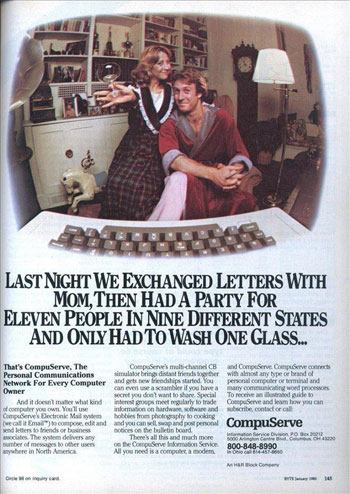

LAST NIGHT WE EXCHANGED LETTERS WITH MOM, THEN HAD A PARTY FOR ELEVEN PEOPLE IN NINE DIFFERENT STATES AND ONLY HAD TO WASH ONE GLASS ...

That's CompuServe, The Personal Communications Network For Every Computer Owner

And it doesn't matter what kind of computer you own.

You'll use CompuServe's Electronic Mail system (we call it Email") to compose, edit and send letters to friends or business associates. The system delivers any number of messages to other users anywhere in North America.CompuServe's multi-channel CB simulator brings distant friends together and gets new friendships started. You can even use a scrambler if you have a secret you don't want to share. Special interest groups meet regularly to trade information on hardware, software and hobbies from photography to cooking and you can sell, swap and post personal notices on the bulletin board.

There's all this and much more on the CompuServe Information Service. All you need is a computer, a modem, and CompuServe. CompuServe connects with almost any type or brand of personal computer or terminal and many communicating word processors. To receive an illustrated guide to CompuServe and learn how you can subscribe, contact or call:

CompuServe

Information Service Division, P.O. Box 20212 5000 Arlington Centre Blvd., Columbus, OH 43220

800-848-8990

In Ohio call 614-457-8650

An H&R Block Company

BYTE January 1983

Fig. 9. Taken from the January, 1983 Edition of Byte Magazine.It’s important to note that CompuServe “popularized” the term ‘Email’ only to the extent that it triggered animosity and ridicule from system users; it was notoriously buggy and feature-light (Compuserve Information Service User’s Guide, 1983).6.12 Misuse #12: “Email” Has No Single InventorThe statement:

"Email has no single inventor. There are dozens, maybe hundreds, of people who contributed to significant incremental ‘firsts’ in the development of email as we know it today. Theirs was a collective accomplishment, and theirs is a quiet pride (or at least was until recent press coverage provoked them). Email pioneer Ray Tomlinson has said of email’s invention that, ‘Any single development is stepping on the heels of the previous one and is so closely followed by the next that most advances are obscured. I think that few individuals will be remembered.’” (Crocker, 2012)

is a misuse of the term “email” --- the system of interlocking parts intended to be a full-scale emulation of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system. The individuals being referenced here as having been “email pioneers” and contributing the to the development of “email,” including Mr. Tomlinson, did not contribute to the development of email, but rudimentary systems for text messaging.

More importantly, this statement is an attempt to feign humility with a “collaborative spirit,” with the deliberate aim of isolating and dismissing Ayyadurai's singular and rightful position as the inventor of email. Ayyadurai did singularly create email, the system of interlocking parts emulating the entire interoffice, inter- organizational paper-based mail system.

The assertion that “email has no single inventor” and “email cannot be invented” are statements, which industry insiders began promoting after an article in the Washington Post appeared that “V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai honored as the inventor of email” (Kolawole, 2012).

For many decades, Raytheon's subsidiary, BBN, has been falsely promoting that it employs the "inventor of email," referring to Ray Tomlinson. Yet, prior to the ceremony to honor Ayyadurai's accomplishment and acquisition of the 50,000 lines of code, tapes, papers and artifacts documenting his invention, these insiders and the SIGCIS group did not expose or ever question the false statements attributing Mr. Tomlinson as “the inventor of email.”Raytheon/BBN put a great deal of effort into their own branding as innovators, by claiming publicly that they are the “inventors of email.” This branding involves juxtaposing the “@” symbol with the face of Ray Tomlinson as the “inventor of email.” In fact, on Raytheon/BBN's home page, the word "innovation" is visually juxtaposed next to the @ logo, with Tomlinson's picture overlaid (Raytheon/BBN, n.d.).

After the Smithsonian ceremony of Ayyadurai’s invention, Raytheon/BBN sent press releases re-asserting that Tomlinson was the “inventor of email.” Concomitant with these efforts, as the timeline shows of attack on Ayyadurai (Abraham, 2014) industry insiders, supported by SIGCIS “historians,” Ray Tomlinson, BBN supporters, and ex-BBN employees continued to perpetuate a false history of email by discrediting Ayyadurai's invention as well as character assassinating him as an inventor and scientist. They used historical revisionism and confusion to redefine and misuse the term email. Through these efforts, they re-declared Tomlinson, and thereby the Raytheon/BBN brand, as the singular “inventor of email,” the “Godfather of email,” and the “King of email” (Hesse, 2012; Hicks, 2012).One ex-BBNer, Dave Walden, though part of the Tomlinson coterie, acknowledged the following:

"Naturally this was discussed on the ex-BBN list. In my view, this "new guy" [Shiva Ayyadurai] has described something not quite like what the rest of us understand when we say ‘email.’" (‘SIGCIS Blog’, 2012)

Walden recognized the misuse of the term "email" as the transmission of text messages between terminals, as was the case with the early messaging systems such as MAIL. This text-message transmission can signify nearly all forms of digital communication—facsimiles, communicating word processors, online bulletin board systems, instant messaging clients, and formal communication.

However, email has a very clear meaning, as established by Ayyadurai in 1978: it is the electronic interoffice, inter-organizational paper-based mail system. It includes all the features one expects from paper mail systems: memo composition, editing, drafts, sorting, archival, forwarding, reply, registered mail, return receipt, prioritization, security, delivery retries, undeliverable notifications, group lists, bulk distribution, and managerial/administrative functions. It had to be fault-tolerant, familiar, and universal. By this definition, Ayyadurai’s invention is the only instance in which this level of integration was first achieved, the same level we all experience nearly every other email products such as Gmail, Hotmail and others.

_______________

References:"A Brief History of Email in the Federal Government." FedTech. Web. 13 July 2012. Aamoth, D. (2013). ‘The Man Who Invented Email’ Time Magazine: Techland,

http://techland.time.com/2011/11/15/the ... nted-email.

Abraham, S. (2014). ‘Vitriol, Attacks, Character Assassination and Defamation of V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai after Smithsonian Acquisition in Major Media’, Retrieved November 12, 2014 from

http://www.historyofemail.com/defamatio ... ithsonian- acquisition.asp.

"Ask.com - What's Your Question?" Ask.com. Web. 13 July 2012.

http://answers.ask.com/computers/intern ... nted_email.

ACM Transactions on Computer Systems 2.1 (1984) pp. 3-23.

ALTO User’s Handbook (1979 September) Palo Alto, CA: XEROX Palo Alto Research Center.

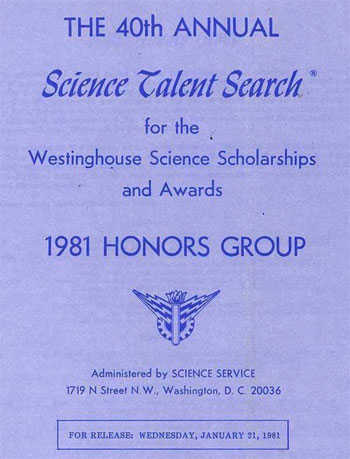

Ayyadurai, V.A.S. (1981). ‘Software Design, Development and Implementation of a High-Reliability Network-Wide Electronic Mail System’, Thomas Edison/Max McGraw Foundation Awards Application, Livingston, NJ, pp. 1-12.

Ayyadurai, V.A.S. (1982a). U.S. Copyright Registration Number: TXu000111775. Email: Computer Program Electronic Mail System. Washington, DC: United States Copyright Office.

Ayyadurai, V.A.S. (1982b). U.S. Copyright Registration Number: TXu000108715. Email User’s Manual: Operating Manual for Electronic Mail System Program. Washington, DC: United States Copyright Office.

Aguilar, M. (2012 February 22). ‘The Inventor of Email Did Not Invent Email?’, Gizmodo.

Bellis, M. "Ray Tomlinson and the History of Email." About.com Inventors. About.com. Web. 13 July 2012.

http://inventors.about.com/od/estartinv ... /email.htm.

Biddle, S. (2012 March 5). Corruption, Lies, and Death Threats: The Crazy Story of the Man Who Pretended to Invent Email. Gizmodo.

Birrell, A. (1980). Grapevine: An Exercise in Distributed Computing,

http://birrell.org/andrew/papers/Grapevine.pdf :272

‘Bitsavers Website’ (2012). Retrieved from

http://www.bitsavers.org/pdf/mit/ctss/C ... _Dec69.pdf on April 7, 2012.

Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. (2011). ‘Open innovation diplomacy and a 21st century fractal research, education and innovation (FREIE) ecosystem: building on the quadruple and quintuple helix innovation concepts and the “mode 3” knowledge production system’, Journal of the Knowledge Economy, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 327-372.

Cerf, V. G. (1979). ‘DARPA activities in packet network interconnection’, In Interlinking of Computer Networks, Springer Netherlands, pp. 287-305.

Cheney, P. H., and Lyons, N. R. (1980). ‘Information systems skill requirements: A survey’, MIS Quarterly, pp. 35-43. Compuserve Information Service User’s Guide.Radio Shack (1983). Tandy Corporation.

Crews, K. D. (1987). University Copyright Policies in ARL Libraries (Vol. 138). Association of Research Libraries.

Crisman et al. Programming Staff Note 39.

http://www.multicians.org/thvv/psn-39.pdf, retrieved April 7, 2012.

Crisman, J.G. (1965). The Compatible Time-Sharing System. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.

Crocker, D. H. (1977).

‘Framework and Functions of the MS Personal Message System’, (No. RAND/R-2134-ARPA), Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA.

Crocker, D.H., Vittal, J.J., Pogran, K.T., Henderson, D.A. (1977), Standard For The Format Of Arpa Network Text Messages,

http://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc733.txt, retrieved April 2012.

Crocker, D.H. (2012 March 20). ‘A history of e-mail: Collaboration, innovation and the birth of a system’, The Washington Post.

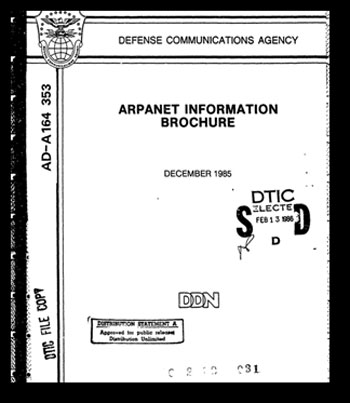

Dennett, S., Feinler, E. J., and Perillo, F. (1985). ‘ARPANET Information Brochure (No. NIC- 50003)’, Sri International, Menlo Park, CA DDN Network Information Center Retrieved

fromhttp://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a164353.pdf on November 21, 2014.

Email. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved September 12, 2014, from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Email.

Email Origin. (1980). In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved September 12, 2014, from

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/de ... ish/e-mail.

Email First Known Use. (1982). In Merriam Webster Dictionary. Retrieved September 12, 2014, from

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/e-mail.

Etzkowitz, H., &Leydesdorff, L. (2000). ‘The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations’, Research Policy, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp.109-123.

Field, R. (2014, August). ‘The First Email System’, Retrieved November 2014, from

http://www.historyofemail.com/the-first ... system.aspFiala, E. R. et al. (1974 May 29) MAXC Operations. Maxc 18.1. Palo Alto, CA: XEROX Palo Alto Research Center.

Flewellen, L. N. (1980). ‘Anomaly in the Patent System: The Uncertain Status of Computer Software’, An. Rutgers Computer & Tech. LJ, Vol. 8, p. 273.

Foster, D. G. (1994 March). ‘In Praise of Lan-Based E-Mail’, TechTrends. Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 25-27.

Gains, J. (1999). ‘Electronic mail—a new style of communication or just a new medium?: An investigation into the text features of e-mail’, English for Specific Purposes, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 81-101.

Garling, C. (2012 June 16). Who Invented Email? Just Ask… Noam Chomsky. Wired.

Gopalakrishnan, R. (June 12, 2014). ‘The “I” Factor in Innovation’, Business Standard.

Hesse, M. (2012): “He put the @ in email”, The Sunday Morning Herald,

http://www.smh.com.au/technology/techno ... -20120425- 1xkx4.html.

"History of Internet/Email." Web. 13 July 2012.

http://www.nethistory.info/History of the Internet/ email.html.

Hicks, J. (2012): “Ray Tomlinson, the inventor of email: 'I see email being used, by and large, exactly the way I envisioned'”, The Verge,

http://www.theverge.com/2012/5/2/2991486/raytomlinson- email-inventor-interview-i-see-email-being-used.

Holmes, M.E. (1995). ‘Don't Blink or You'll Miss It: Issues in Electronic Mail Research”, Communication Yearbook, Vol. 18, pp. 454-463.

“IETF Tools” (n.d.). Retrieved September 12, 2012, from http:http://tools.ietf.org."The Invention of Email."

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/. 1998. Web. 13 July 2012.

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~scotch/in ... _email.pdf.

Kuo, F. F. (1979). Message Services in Computer Networks, Springer Netherlands.

Kolawole, E. (2012). “Smithsonian acquires documents from inventor of ‘EMAIL’ program”. The Washington Post.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/ ... story.htmlLemley, M. A., Menell, P. S., Merges, R. P., & Samuelson, P. (2006). Software and Internet Law. Aspen Publishers, Inc.

Leydesdorff, L., & Etzkowitz, H. (1996). ‘Emergence of a Triple Helix of university— industry—government relations’, Science and Public Policy, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 279-286.

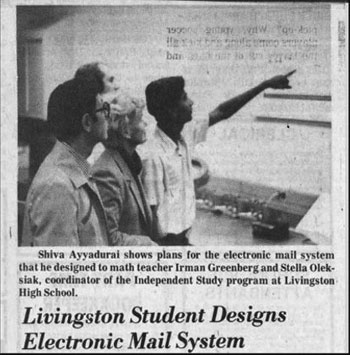

‘Livingston Student Designs Electronic Mail System’, (1980, October 30). West Essex Tribune, p. B8.

Lyons, R. (1980). ‘A Total AUTODIN System Architecture,’ IEEE Transactions on Communications, Vol. 28 No. 9, pp. 1467-1471.

Malgieri, W. (1982). Implementation of Command and Control Training Systems, COMPUTING ANALYSIS CORP, ARLINGTON VA.

Markus, M. L. (1994). ‘Electronic mail as the medium of managerial choice’, Organization Science, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp, 502-527.

Marold, K. A., and Larsen, G. (1997, April). ‘The CMC range war: an investigation into user preferences for email and vmail’, In Proceedings of the 1997 ACM SIGCPR conference on Computer personnel research, pp. 234-239. ACM.

McLeod Jr., R., and Bender, D. H. (1982). ‘The integration of word processing into a management information system’, MiS Quarterly, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 11-29.

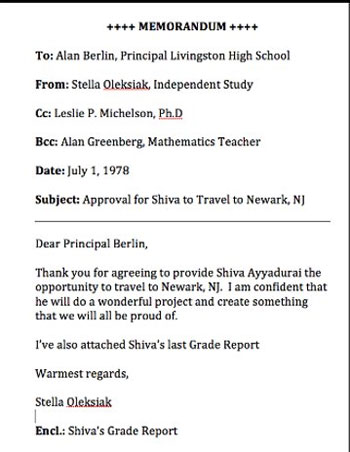

Michelson, L.M. (April 2012). ‘Recollections of a Mentor and Colleague of a 14-Year-Old, Who Invented Email in Newark, NJ’, Retrieved October 2014, from

http://www.inventorofemail.com/va_shiva ... chelson.as p.

Michelson, L.M., Bodow, M., Brezenhoff, T. and Field, R. (2013, September 17). ‘Launching of Innovation Corps’ [Video file], University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ. Retrieved from

http://www.innovationcorps.org/launchin ... tion-corps.

Michelson, L.M. (August 2014). ‘The Invention of Email’, Retrieved October 2014, from

http://www.historyofemail.com/the-invention-of-email.

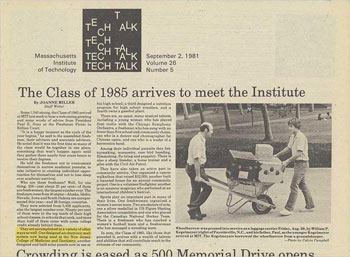

Miller, J. (1981, Sepember 2). ‘Incoming Class of 1985 Arrives to Meet Institute’, MIT Tech Talk, Vol. 26 No. 5 p.1.

Morrisett, L.N. (1996). ‘Habits of Mind and A New Technology of Freedom’, First Monday, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 1-7.

Mullish, H. (1978). ‘New York University Summer High School Program in Computer Science’, Certificate of Successful Completion with Distinction, New York University, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York, NY.

Nanos, J. (2013). ‘Return to Sender’, Boston Magazine, Boston, MA.

Nightingale, D.J. and S. Song (2012). "False Claims About Email."

http://www.inventorofemail.com/. 2012. Web. 13 July 2015.

Nightingale, D.J. (2014a). ‘The Five Myths of Email’ Retrieved November 13, 2014, from

http://www.historyofemail.com/the-five- ... -email.aspNightingale, D.J., and S. Song (2014b). "Revisionism of History by Tom Van VleckAfter the News of Ayyadurai's Invention of Email." The Inventor of Email. 2012. Web. 13 July 2015.

http://www.inventorofemail.com/Historic ... -Vleck.asp.

Ngwenyama, O. and Lee, A. (1997). ‘Communication Richness in Electronic Mail: Critical Social Theory and the Contextuality of Meaning’, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 145-167.

Padlipsky, M.A. (2000). ‘And they argued all night…’ The ARPANET Source Book,

http://tinyurl.com/83739l7, retrieved April 7, 2012. pp. 504-509.

Patel, N. V. (2003). ‘e-Commerce technology’, E-business Fundamentals, Routledge, New York, pp. 43-63.

Pearl, J. A. (1993). ‘The E-Mail Quandary’, Management Review, Vol. 82 No. 7, pp. 48-51.

Pogran, K. (2012). ARPANET contributor,

http://www.multicians.org/mx-net.html, retrieved April 2012.

Postel, J. B., Sunshine, C. A., and Cohen, D. (1981). ‘The ARPA internet protocol’, Computer Networks, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 261-271.

Postel, J. B. (1982a). ‘SMTP-Simple Mail Transfer Protocol’, RFC 821.

Postel, J. B. (1982b). ‘Summary Of Computer Mail Services Meeting Held at BBN on 10 January 1979’, RFC 808.

http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc808.

Ramey, C. (1993). ‘Emm: An Electronic Mail Management System for UNIX’, Masters Thesis Project Report, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH pp. 1-49. Retrieved October, 2012, from

http://tiswww.case.edu/php/chet/info/emm.report.ps.

Robinson, J.G. (1983). Introduction. An Overview of Electronic Mail Systems. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.

Rocca, M. (2015): “Inventor of Email”, CBS Dream Team - Innovation Nation with Mo Rocca,

http://cbsdreamteam.com/the-henry-fords ... -of-email/.

Raytheon/BBN. (n.d.). Retrieved May 12, 2012, from

http://www.bbn.com‘SIGCIS Blog’ (2012). Retrieved from

http://www.sigcis.org on April 17, 2012.

Schroeder, Michael D., Andrew Birrell, and Roger Needham (1984). "Experience with Grapevine: The Growth of a Distributed System." ACM Transactions on Computer Systems 2.1, 3-23.

Shicker, P. "Service Definitions in a Computer Based Mail Environment” Computer Message Systems. Ottawa, Canada: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1981. 159-171.

Smith, C. (2011, August 30). ‘ “Email” Anniversary: V.A. Shiva's EMAIL Copyright Issued August 30, 1982’, Huffington Post.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History (2012, February 16). Artifacts of Invention of Email from V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai’s 1978 Invention. Submitted to Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. 10th Street & Constitution Ave. NW, in Washington, D.C. 20560.

Stanford Department of Computer Science & Xerox Corporation (1980 September). Welcome to ALTO Land. Stanford ALTO User’s Manual. Department of Computer Science, Stanford University.

Tesler, Larry (2012). Retrieved from

http://tinyurl.com/83nlq32 on April 7, 2012.

Thompson, G.A. (1981) What’s the Message. Computer Message Systems. pp. 1-6. Ottawa, Canada: North-Holland Publishing Company.Tomlinson (2012).

http://openmap.bbn.com/~tomlinso/ray/fi ... frame.html, retrieved April 7, 2012

Trudell, L. et al. (1984) Options for electronic mail. Distributed Electronic Mail Networks. p. 67. White Plains, NY: Knowledge Industry Publications.

Tsuei, H. T. (2003). U.S. Patent No. 6,654,779. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Van Vleck, T. (2001) “The History of Electronic Mail,”

http://web.archive.org/web/201107202154 ... ailhistory. html, (retrieved April 2012.)

Vallee, Jacques (1984). Computer Message Systems. New York: McGraw-Hill .

Vittal, John (1981). MSG: A Simple Message System. Cambridge, MA: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1981.

Wang Systems Newsletter 14 (1979 July).Whole ALTO World Newsletter (1977 December 31).

Westinghouse Science Talent Search (1981, January 21), ‘Software Design, Development and Implementation of High Reliability, Network-Wide, Electronic Mail System’, The 40th Annual Science Talent Search for the Westinghouse Science Scholarships and Awards: 1981 Honors Group, Science Service, Washington, DC.

Yates, J. (1989) ‘The Emergence of the Memo as a Managerial Genre’, Management Communication Quarterly, Vol. 2, pp. 485-510.

Yates, J. and Orlikowski, W. (1992) ‘Genres of Organizational Communication: A Structurational Approach to Studying Communication and Media’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 299-326.

_______________

Notes:

Deborah J. Nightingale

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

email:

[email protected]Sen Song

Tsinghua University, School of Medicine

Beijing, Haidian, China

Leslie P. Michelson, Robert Field

Rutgers University, High Performance Computing, Information Services & Technology

Newark, NJ 07103, USA