by Deborah J. Nightingale, Ph.D.

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The Fourth Article in The History of Email Series

(An extract from False Claims About Email)

This article exposes five myths about the origin of email:

Myth #1: “Email was created on the ARPANET”

Myth #2: “Ray Tomlinson invented ‘email’ and sent the first ‘email’”

Myth #3: “The ‘@’ symbol equals the invention of ‘email’”

Myth #4: “RFCs demonstrate ‘email’ existed prior to 1978”

Myth #5: “CTSS, developed in 1960s, is ‘email’

These myths have been perpetuated through the misuses of the term “email” to refer to methods for the simple exchange of text messages as email. Methods for simply exchanging text messages date back to the Morse code telegraph of the 1800s, the genesis of short messaging such as SMS, Texting, Instant Messaging and Twitter, but certainly not email.

Prior to 1978, the term “email” did not even exist in the modern English language, as verified by the Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam Webster, two of the world’s most eminent dictionaries.

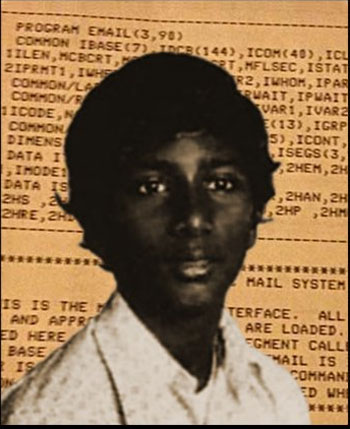

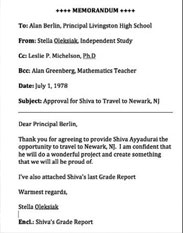

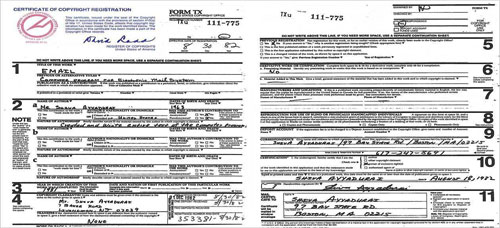

Email was precisely defined in 1978 when V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai, then 14-years-old, created the term “email” to name his computer program, which was the first full-scale electronic replication of the interoffice mail system consisting of the now-familiar components of email: Inbox, Outbox, Folders, Attachments, Memo, Address Book, Forwarding, Composing, etc., the system we all experience today in other email systems as Gmail, HotMail, Yahoo!

Sometime after Shiva’s invention of email in 1978, a group of industry insiders, public relations experts and “historians” loyal to Raytheon/BBN, a multi-billion dollar company which had predicated its entire brand on the claim it had “invented email”, began purposely misusing the term “email” to refer to its developments in text messaging, done prior to 1978 as “email”, in order to hijack credit for the invention from the 14-year-old boy.

A Fabricated “Controversy”

When Shiva was given international recognition, following the Smithsonian’s acquisition of his computer code, papers and artifacts, documenting his invention of email, these industry insiders then resorted to fabricating a “controversy” to confuse journalists and the public on email’s true origins.

As Noam Chomsky, MIT Institute Professor and one of the world’s most respected scholars of our time, observed, in Wired:

“Given the term email was not used prior to 1978, and there was no intention to emulate ‘… a full-scale, inter-organizational mail system,” as late as December 1977 [by the ARPANET], there is no ‘controversy’ here, except the one created by industry insiders, who have a vested interest.”

-- (Wired, Who Invented Email, Just Ask…Noam Chomsky, June 6, 2012)

What sparked this “controversy” was that the documentation unequivocally proved that Shiva, as a 14-year-old boy in 1978, was the first to create the electronic version of the interoffice mail system; the first to call it “email”, a term he coined that did not exist in the English language; and the first to receive formal and official recognition for the invention by the U.S. Government.

When a young Washington Post reporter shared these facts, in a feature article shortly following the Smithsonian acquisition, she and the editorial board of the Washington Post were attacked and barraged by this coterie of industry insiders including consultants, employees, alumni and an "Internet cabal", as referred by Boston Magazine, of SIGCIS “historians” with ties to Raytheon/BBN.

During this melee, Noam Chomsky responded, “What continue[s] to be deplorable are the childish tantrums of industry insiders who now believe that by creating confusion … they can distract attention from the facts.”

These tantrums were sensationalized by tabloids such as Gizmodo, the Blaze, TechDirt, and the Verge, which did little primary research, rather simply parroting and escalating the vitriol, defamation and character assassination of Shiva, while attacking and bullying journalists, including technology editors such as Doug Aamoth of TIME, who had earlier written a well-researched piece, The Man Who Invented Email, based on reviewing the actual documentation.

In the midst of the chaos and confusion, the Washington Post responded by appeasing the childish behavior of these insiders by a “Mea Culpa” and “corrections”. The Washington Post did a significant disservice to the public, by not having the courage to stand by the documented facts, and not doing the primary research on the myths and claims made by these industry insiders, which would have revealed the significant economic interests behind the vitriol and defamation to discredit Shiva’s work.

Setting the Record Straight

I am pleased to provide an extract of five key myths of the facts of email's origin, based on the misuses of the term "email".

Popular sites such as Wikipedia, unfortunately, continue to promulgate the myths of email’s history. Industry insiders dominate and monopolize such forums, and immediately remove even documented citations and facts, which expose and counter their false claims on email’s origin.

There is a simple way to understand the myths about email’s history by realizing a single and fundamental concept: Email is a System.

As an MIT professor, who led MIT’s Sociotechnical Systems Research Center for nearly half a decade, and served on the faculty in MIT’s Engineering Systems Division for over 17 years, my research has focused on systems and, specifically, developing new methodologies for architecting large-scale enterprise systems.

I spent nearly 40 years of my career helping some of the largest global companies in the world as well as military organizations understand the complexity of such large-scale systems in order to enhance their performance.

So, I know a bit about systems.

The classic definition of a system, by the eminent systems scientist Eberhardt Rechtin, is:

“A set of different elements so connected or related as to perform a unique function not performable by the elements alone.”

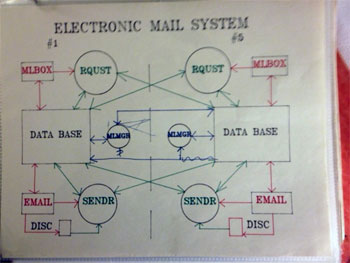

Email, by definition, as a system, is a set of different elements, so connected, as to be the direct electronic emulation of the interoffice mail system, as Robert Field has explained in The First Email System. The interoffice mail system consisted of the now-familiar components of email: Inbox, the Memo (“To:”, “From:”, “Date:”, “Subject:”, “Body:”, “Cc:”, “Bcc:”), Forwarding, Composing, Drafts, Edit, Reply, Delete, Priorities, Outbox, Folders, Archive, Attachments, Return Receipt, Carbon Copies (including Blind Carbon Copies), Sorting, Address Book, Groups, Bulk Distribution, etc.

The elements of email, which Shiva invented, functioned together to provide the foundations of complex interoffice, inter-departmental, inter-organizational communications. If you took away any one element or part of this system, such as the ability to attach other materials, Attachments, or the use of Folders or the ability to Forward or Prioritize, your ability to function and communicate with co-workers was greatly impaired in the office environment.

This is why email is a “system”, because you needed all elements to function cohesively together for office communications to take place.

When we understand that email is a system, we can realize that there is no “controversy” except the one fabricated by those insiders to confuse and convince us that email existed prior to 1978.

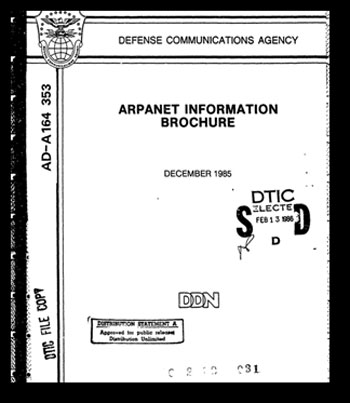

MYTH #1: “EMAIL” WAS CREATED ON THE ARPANET

This statement is a misuse of the term “email”, since the invention referenced in this statement is command-line protocols for the simple transfer of electronic text messages, not email – the electronic replication of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper mail system.

ARPANET researchers, as history shows, were never interested in creating email. The famous RAND Report written by David Crocker, a leading ARPANET researcher, in December of 1977, is unequivocal as to the lack of intention of ARPANET researchers to create email, the inter-organizational mail system.

In December of 1977, Mr. Crocker wrote:

"At this time, no attempt is being made to emulate a full-scale, inter-organizational mail system [p.4]…. The fact that the system is intended for use in various organizational contexts and by users of differing expertise makes it almost impossible to build a system which responds to all users' needs. [p.7]”

— Crocker, David. Framework and Function of the "MS" Personal Message System. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, December 1977.

Since the system is to be used for communication which is exemplified in older and heavily-exercised technology, it is assumed that users have an extensive conceptual model of the communication domain. It is further assumed that a system which performs in ways which deviate from that model will be viewed as "idiosyncratic" and impeding the efforts of the user. Problems occurring during this sort of interaction can be expected to be as irritating as having a pen which leaks or a typewriter with keys that jam. Therefore, a major design goal for MS is to provide an integrated set of necessary and sufficient functions which conform to the target user's cognitive model of a regular office-memo system. At this stage, no attempt is being made to emulate a full-scale inter-organization mail system....

The level of the MS project effort has also had a major effect upon the system's design. To construct a fully-detailed and monolithic message processing environment requires a much larger effort than has been possible with MS. In addition, the fact that the system is intended for use in various organizational contexts and by users of differing expertise makes it almost impossible to build a system which responds to users' needs. Consequently, important segments of a full message environment have received little or no attention and decisions have been made with the expectation that other Unix capabilities will be used to augment MS. For example, MS has fairly primitive data-base management (i.e., filing and cataloging) facilities and message folders have been implemented in a way which allows them to be modified by programs, such as text editors, which access them directly, rather than through the message system.

-- Framework and Functions of the "MS" Personal Message System: A Report prepared for Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, by David H. Crocker

The ARPANET researchers were focused on creating methods for the simple exchange of text messages, in the lineage of the telegraph, and not on creating an electronic version of the interoffice, inter-organizational mail system.

During the Civil War, the military, for example, relied on the telegraph as a core and strategic medium of communication for sending short text messages. The telegraph inspired continuing work by military research organizations. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), for example, funded the ARPANET to develop methods for transport of simple text messages across computers during the 1960s and 1970s.

The purpose of the telegraph, unlike the interoffice mail system, was to transport text messages electronically across wires, using cryptic codes.

Telegraph operators sending and receiving text messages.

The interoffice system, unlike the telegraph, was a system used for transporting interoffice paper mail across offices, departments, organizations and buildings, using people, cars, trucks and pneumatic tubes that were prevalent across many offices.

Pneumatic tubes, a critical component of the interoffice mail system.

Just as the telegraph was not the interoffice mail system, the ARAPNET work was not email, but at best was a precursor to what we know today as Texting or Text Messaging. Therefore, statements that claim email was invented by the ARPANET are simply false and conflate the ARPANET work.

In fact, prior to 1978, the ARPANET referred to their work as “Text Messaging” or “Messaging” never as “email”. After the invention of email by Shiva in 1978, ARPANET alumni began to refer to their work as “email”.

This important distinction between the telegraph and the interoffice mail system helps us to understand the myth of the statement that “Email was created on the ARPANET”.

The military had little interest in sending interoffice memoranda on the battlefield in the 1970s - this is not what ARPANET was built for.

MYTH #2: RAY TOMLINSON INVENTED "EMAIL" AND SENT THE FIRST "EMAIL" MESSAGE

This statement is a misuse of the term “email” since Ray Tomlinson did not invent email - the electronic replication of of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper mail system. The invention referenced in such statements and attributed to Mr. Tomlinson is the simple exchange of text messages between computers.

In fact, what Mr. Tomlinson did was to simply modify a pre-existing program called SNDMSG, which he himself did not write. The minor modifications he made enabled the exchange of simple text messages across computers. The resulting SNDMSG however, was unusable by ordinary people, and required a set of highly technical computer codes that the sender had to type to transfer a message from one computer to another. Such cryptic codes were far too technical, and could not be used by a secretary or office worker.

As historical references demonstrate, SNDMSG, far from being email, was at best, a very rudimentary form of text messaging. As John Vittal, an early leading pioneer in electronic messaging researcher, observed:

“The very simple systems (SNDMSG, RD, and READMAIL) did not integrate the reading and creation functions, had different user interfaces, and did not provide sufficient functionality for simple message processing.”—Vittal, John. MSG: A Simple Message System. Cambridge, MA: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1981.

Moreover, Mr. Tomlinson, to his own admission said that what he created was a “no-brainer” and a minor contribution.

“I was making improvements to the local inter-user mail program called SNDMSG. The missing piece was that the experimental CPYNET protocol had no provision for appending to a file; it could just send and receive files. Adding the missing piece was a no-brainer—just a minor addition to the protocol.”—Tomlinson, Ray, retrieved April 7, 2012.

http://openmap.bbn.com/~tomlinso/ray/fi ... frame.html

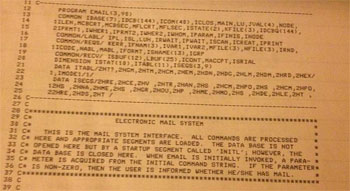

SNDMSG was less than a rudimentary form of text messging, and a far cry from email, the system created by Shiva which consisted of 50,000 lines of code that was the full-scale emulation of the entire interoffice mail system, by definition.

MYTH #3: THE “@” SYMBOL EQUALS THE INVENTION OF "EMAIL"

This is a misuse of the term “email” since it implies that the “@” symbol is equivalent to inventing email - the electronic replication of the interoffice, inter-organizational paper mail system.

The “@” symbol is used in an email address to separate the user name from the domain name. The invention referenced in the above statement is the use of the “@” symbol to distinguish two computers when sending a text message. The “@” symbol is not a necessary component to distinguish two computers, in some cases “-at” was used, as verified by Tom Van Vleck:

“Because the ‘@’ was a line kill character in Multics, sending mail from Multics to other hosts used the control argument -at instead.”—Van Vleck, Tom. History of Electronic Mail, http://www.multicians.org/thvv/mail-history.html, April 7, 2012.

In the first email system developed by Shiva, the symbol “.” was used to distinguish different computers. Equating the “@” symbol with the invention of email was a major branding and public relations effort of Raytheon/BBN. The “@” symbol is not email.

As M.A. Padlipsky, the eminent electronic messaging pioneer, an MIT graduate, a member of the ARPANET team, and a close contemporary of Mr. Tomlinson, observed of Raytheon/BNN’s long history of self-promotional activities:

“[T]he BBN guys - who always seemed to get to write the histories and hence always seemed to have claimed to have invented everything, anyway, perhaps because BBN was the only "for-profit" to furnish key members of the original Network Working Group.”—Padlipsky, M.A., ARPANET contributor and author of more than 20 RFC specifications), “And they argued all night….”,

http://archive.is/dx2TK

To conclude, the creation of the “@” symbol to distinguish computers, does not in any way equate to the invention of email.

MYTH #4: RFCS DEMONSTRATE "EMAIL" EXISTED PRIOR TO 1978

Requests for Comments (RFCs) were simply written documentations, not an email computer program, nor an email system. RFCs were literally meeting notes that recorded the meetings of electronic messaging researchers in the 1970s. As such, this is a flagrant misuse of the term “email”.

For example, sensationalist statements, such as the one by issued by Gizmodo in 2012 stating:

“[E]mail underpinnings were further cemented in 1977's RFC 733, a foundational document of what became the internet itself.”

are, at best misinformed, and completely lack understanding that email was the electronic interoffice mail system. Furthermore, email does not need the Internet to operate. Email systems initially ran on Wide Area Networks (WANs) and Local Area Networks (LANs), independent of the Internet and ARPANET. In fact, even today, one doesn’t need the Internet to run email.

Moreover, RFC 733 was a document to define an attempted standard that was never even fully accepted. The very term “RFC” means “Request for Comments”. It was a document created from meeting notes, and proposed ideas for message format and transmission, but said little about feature sets of individual electronic messaging or mail systems.

As the opening of RFC 733, it states:

“This specification is intended strictly as a definition of what is to be passed between hosts on the ARPANET. It is not intended to dictate either features which systems on the Network are expected to support, or user interfaces to message creating or reading programs.”— http://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc733.txt

Therefore, RFCs do not demonstrate that email existed prior to 1978. What RFCs demonstrate are that meetings and discussions were taking place on defining methods to exchange text messages, not the creation of email.

MYTH #5: CTSS, DEVELOPED IN 1960's, IS "EMAIL"

This is a misuse of the term “email” since the reference to CTSS MAIL (Computer Time Sharing System), the method referenced and attributed to MIT, was an early text messaging system, not a version of email --- the system of interlocked parts intended to emulate the interoffice mail system.

This invention, MAIL, allowed a CTSS user to transmit a file, written in a third-party editor, and encoded in binary-coded decimal format (BCD), to other CTSS users. The delivered message would be appended to the front of a file in the recipient’s directory that represented the aggregate of all received messages. This flat-file message storage placed strict constraints on the capacity of MAIL, and required users to traverse and review all messages one-by-one; search and sort mechanisms were not available.

The design choices in MAIL—lack of search and sort facilities, need for an external editor, dependence on CTSS-specific user IDs, and flat-file message storage—put strict constraints on the use and capacity of the command. It was well-suited to the low-volume transmission of informal (i.e. unformatted) messages, like text messaging of today.

The creator of MAIL, Tom Van Vleck, admitted this fact. Van Vleck stated:

“The proposed uses [of MAIL] were communication from ‘the system’ to users, informing them that files had been backed up, communication to the authors of commands with criticisms, and communication from command authors to the CTSS manual editor.” -http://www.multicians.org/thvv/mail-history.html, retrieved April 18th, 2012

Those who promoted MAIL as "email," when the term "email" did not even exist in 1965, were attempting to redefine "email" as a command-driven program that transferred BCD-encoded text files, written in an external editor, among timesharing system users, to be reviewed serially in a flat-file.

One would be hard-pressed to draw a historical straight line from MAIL to today’s email systems. MAIL was not "email", but a text messaging command line system, at best. Historically, one can give credit to MAIL as a predecessor of today’s electronic bulletin board systems or modern blog postings.

CONCLUSION

Email is a system of interconnected parts that was designed with a clear aim to emulate another system: the interoffice paper-based mail system, a system of interlocking parts Inbox, Memo, Outbox, Folders, Address Book, etc. the elements of the email system used today by billions of people worldwide.

From our review of the five myths about email, one can understand developments such as the ARPANET efforts, early programs for sending and receiving messages, the “@” sign, technical specifications known as RFCs, and MAIL, which were claimed to be “email”, were not email - the system of interlocked parts for emulating the interoffice mail system.

Those developments, while significant to the advancement of the Internet, aimed to solve various problems, but were not intended to substitute for the interoffice paper mail system --- email.

Acknowledgements

For those interested in the unabridged version of this article, kindly refer to the False Claims section on http://www.inventorofemail.com which Dr. Sen Song and I organized and edited in 2012. Our compiling, editing and organizing the claims would not have been possible without the Herculean efforts of Devon Sparks and Lorraine Monetti, who discovered and annotated the documents, referenced therein.

About Deborah J. Nightingale

Deborah J. NightingaleDeborah J. Nightingale, Ph.D. is a world-renowned expert in enterprise systems transformation and architecting. For nearly 17 years, Dr. Nightingale served as a Professor of Practice of Engineering Systems, and Aerospace and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). For the past nearly half a decade, she led the MIT Sociotechnical Systems Research Center. Today, she works with some of world’s leading organizations, bringing her strategic systems thinking approaches to transform their enterprises to achieve desired capabilities such as sustainability, flexibility or enhanced innovation and entrepreneurship.

Prior to joining MIT, Dr. Nightingale headed up Strategic Planning and Global Business Development for AlliedSignal Engines. While at AlliedSignal she also held a number of executive leadership positions in operations, engineering, and program management, participating in enterprise-wide operations from concept development to customer support. Prior to joining AlliedSignal, she worked at Wright-Patterson AFB where she served as program manager for computer simulation modeling research, design, and development in support of advanced man-machine design concepts.

Dr. Nightingale has a Ph.D. from The Ohio State University in Industrial and Systems Engineering. In addition, she holds MS and BS degrees in Computer and Information Science from The Ohio State University and University of Dayton, respectively. She is a member of the National Academy of Engineering, Past-President and Fellow of the Institute of Industrial Engineers, and co-Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Enterprise Transformation. She is the author of numerous articles and books, including Beyond the Lean Revolution: Achieving Successful and Sustainable Enterprise Transformation and Architecting the Future Enterprise (Spring 2015, MIT Press). Dr. Nightingale is a frequent keynote speaker and serves on a number of boards and national committees, where she interacts extensively with industry, government and academic leaders.