Case 1:16-cv-10853-JCB Document 1 Filed 05/10/16

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

SHIVA AYYADURAI, an individual,

Plaintiff,

v.

GAWKER MEDIA, LLC, a Delaware limited liability company; SAM BIDDLE, an individual, JOHN COOK, an individual, NICHOLAS GUIDO ANTHONY DENTON, an individual, and DOES 1-20,

Defendants.

CASE NO.

COMPLAINT

DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL

Plaintiff Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai, by and through his undersigned attorneys, sues Defendants Gawker Media, LLC, Sam Biddle, John Cook, Nicholas Guido Anthony Denton, and DOES 1-20 (collectively, “Defendants”), and respectfully makes the following allegations.

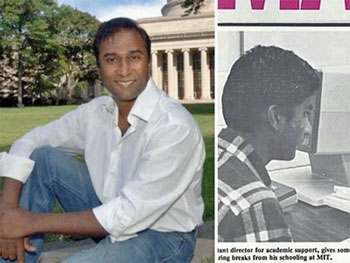

SUMMARY OF THE CASE1. Dr. Ayyadurai is a world-renowned scientist, inventor, lecturer, philanthropist and entrepreneur. In 1978, Dr. Ayyadurai invented email: the electronic mail system as we know it today. On November 15, 2011, TIME magazine published an article titled “The Man Who Invented Email,” which outlines the backstory of email and Dr. Ayyadurai’s invention. In June 2012, Wired magazine reported: “Email … the electronic version of the interoffice, interorganizational mail system, the email we all experience today, was invented in 1978 by [Dr. Ayyadurai] …. The facts are indisputable.” In July 2015, CBS reported on The Henry Ford Innovation Nation, hosted by Mo Rocca: “Next time your fingers hit the keyboard to write a quick email, you might want to say, thank you to Shiva Ayyadurai…. he is credited with inventing email …. in the late 1970s.”

2. Dr. Ayyadurai holds four degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): a B.S. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, an M.S. in Visual Studies, an M.S. in Mechanical Engineering, and a Ph.D. in Biological Engineering. Dr. Ayyadurai has been recognized internationally for his developments in early social media portals, email management technologies, and contributions to medicine and biology. He has been a speaker at numerous international forums, where he has discussed email, science and technology, among other topics. Dr. Ayyadurai also operates his own research and education center: the International Center for Integrative Systems in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

3. In 2012, Defendants published two false and highly defamatory articles about Dr. Ayyadurai on their website at Gizmodo.com to discredit Dr. Ayyadurai’s invention. The articles falsely trace the origin of email and call Dr. Ayyadurai a liar, a “fraud” and responsible for “a misinformation campaign.” In 2014, Defendants again published a defamatory article about Dr. Ayyadurai, this time on their Gawker.com website, calling Dr. Ayyadurai a “fraud,” a “renowned liar,” and a “big fake,” among other things. These statements are all demonstrably false.

4. Defendants’ false and defamatory statements have caused substantial damage to Dr. Ayyadurai’s personal and professional reputation and career. As a result of Defendants’ defamation, Dr. Ayyadurai has been publicly humiliated, lost business contracts and received a slew of criticism relating to Defendants’ false accusations and statements. Defendants’ wrongful acts, which have been repeated, have left Dr. Ayyadurai with no alternative but to file this lawsuit. Dr. Ayyadurai seeks an award of no less than $35 million in damages.

THE PARTIES5. Plaintiff is a resident and domiciliary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, County of Middlesex.

6. Upon information and belief, Gawker Media, LLC (“Gawker”) is a Delaware limited liability company with its principal place of business located in New York City, New York.

7. Upon information and belief, defendant Sam Biddle (“Biddle”) is an individual, domiciled in the State of New York. At all relevant times, Biddle was a senior staff writer at Gawker.

8. Upon information and belief, defendant John Cook (“Cook”) is an individual, domiciled in the State of New York. At relevant times, Cook was an editor and writer at Gawker.

9. Upon information and belief, defendant Nicholas Guido Anthony Denton aka “Nick Denton” (“Denton”) is an individual, domiciled in the State of New York. At all relevant times, Denton was Founder and CEO of Gawker.

10. Upon information and belief, Defendants, and each of them, were and are the agents, licensees, employees, partners, joint-venturers, co-conspirators, owners, principals, and employers of the remaining Defendants and each of them are, and at all times mentioned herein were, acting within the course and scope of that agency, license, partnership, employment, conspiracy, ownership, or joint venture. Upon further information and belief, the acts and conduct herein alleged of each of the Defendants were known to, authorized by, and/or ratified by the other Defendants, and each of them.

JURISDICTION AND VENUE11. This Court has personal jurisdiction over Defendants because they have minimum contacts with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

12. The Court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a) because there is complete diversity of the parties to this action and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

13. Venue is proper in this district pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1391(b), in that a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred here.

FACTS RELEVANT TO ALL CAUSES OF ACTION

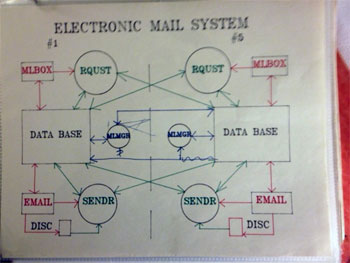

DR. AYYADURAI’S INVENTION OF EMAIL14. In or about 1978, Dr. Ayyadurai created email: a computer program that created an electronic version of a paper-based interoffice mail system, which allowed mail to be sent electronically. Like the email we use today, Dr. Ayyadurai’s invention offered many features for users, such as, to send electronic mail messages to an “inbox,” save sent messages in an “outbox,” add “attachments,” and allow users to create an “address book” that included email addresses of multiple individuals.[

15. Dr. Ayyadurai invented email while working as a Research Fellow at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. His role there was to design an electronic system to mirror the features of the interoffice (or inter-organizational) paper mail system, which consisted of the Inbox, Outbox, Drafts, Folders, Memo, Attachments, Carbon Copies, Blind Carbon Copies) (i.e., “To:,” “From:,” “Date:,” “Subject:,” “Body:,” “Cc:,” “Bcc:”), Return Receipt, Address Book, Groups, Forward, Compose, Edit, Reply, Delete, Archive, Sort, Bulk Distribution, etc. These features are now the familiar parts of every modern email system.

16. The invention of email was made by Dr. Ayyadurai as an attempt to manage the complexity of interoffice communications, and also to reduce the use of paper documents. Dr. Ayyadurai designed email so it was accessible to ordinary people with little or no computer experience, at a time when mainly highly-trained technical people could use a computer.

17. Dr. Ayyadurai wrote nearly 50,000 lines of computer code to implement the features of the interoffice mail system into his computer program.

18. Dr. Ayyadurai named his computer program “email”. He was the first person to create this term, because he was inventing the “electronic” (or “e”) version of the interoffice paper-based “mail” system. His naming of “email” also arose out of the limited parameters of the programming language and operating system, which limited program names to all capital letters and a five-character limit. Thus, his selection of the letters “E” “M” “A” “I” and “L.”

19. At the time of Dr. Ayyadurai’s invention of email, software inventions could not be protected through software patents. It was not until 1994 that the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled that computer programs were patentable as the equivalent of a “digital machine.” However, the Computer Software Act of 1980 allowed software inventions to be protected to a certain extent, by copyright. Therefore, in or about 1981, Dr. Ayyadurai registered his invention with the U.S. Copyright Office. On August 30, 1982, Dr. Ayyadurai was legally recognized by the United States government as the inventor of email through the issuance of the first Copyright registration for “Email,” “Computer Program for Electronic Mail System.” With that U.S. Copyright of the system, the word “email” entered the English language.120. In summary, Dr. Ayyadurai was the first to convert the paper-based interoffice mail system (inbox, outbox, folders, attachments, etc.) to its electronic version; the first to call it “email”; and received the first U.S. Copyright for email that legally recognized Dr. Ayyadurai as the inventor of email.

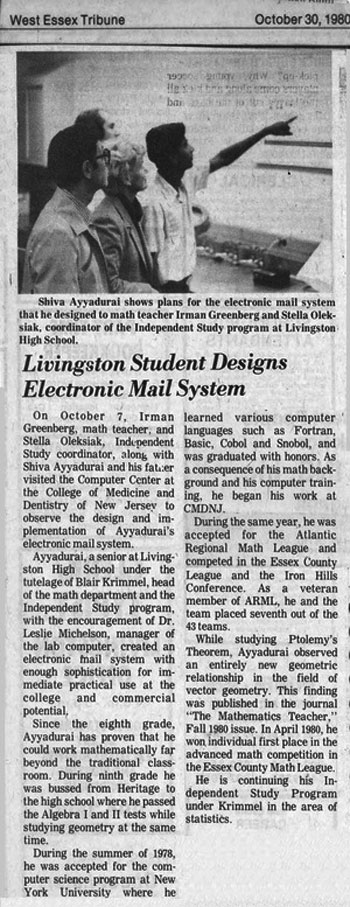

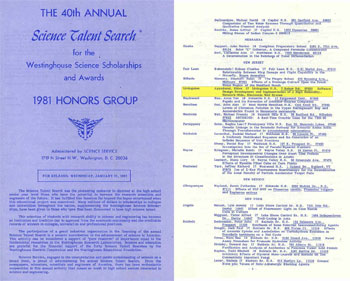

21. On or about November 15, 2011, TIME magazine published an article titled “The Man Who Invented Email,” which outlines the history of email and Dr. Ayyadurai’s invention. The article states that “email – as we currently know it – was born” when Dr. Ayyadurai created it replicating an interoffice mail system at the University of Medicine and Dentistry in Newark, New Jersey. The article states that “the original system was set up for doctors to communicate electronically using the [physical] template they were already used to” and the interface “hasn’t changed all that much” in becoming the email system we know and use today. The TIME article also states that in “1981, Shiva took honors at the Westinghouse Science Awards for his ‘High Reliability, Network-Wide, Electronic Mail System’” and that in 1982 he “won a White House competition for developing a system to automatically analyze and sort email messages.”

22. In June 2012, Wired magazine reported that: “Email … the electronic version of the interoffice, inter-organizational mail system, the email we all experience today, was invented in 1978 by [Dr. Ayyadurai] …. The facts are indisputable.”

23. In July 2015, CBS reported on The Henry Ford Innovation Nation, hosted by Mo Rocca: “Next time your fingers hit the keyboard to write a quick email, you might want to say, thank you to Shiva Ayyadurai.... he is credited with inventing email…. in the late 1970s.”

GAWKER DEFENDANTS’ FALSE AND DEFAMATORY STATEMENTS ABOUT DR. AYYADURAI24. On or about February 22, 2012, Defendants published on their website, Gizmodo.com, an article authored by Mario Aguilar with the headline: “The Inventor of Email Did Not Invent Email?” (the “February 2012 Article”), a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit A. The February 2012 Article falsely states: “Ayyadurai is a fraud.”

25. On or about March 5, 2012, Defendants published on Gizmodo.com a lengthy story authored by Sam Biddle with the headline: “Corruption, Lies, and Death Threats: The Crazy Story of the Man Who Pretended to Invent Email” (the “March 2012 Article”), a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit B. The March 2012 Article contains multiple false statements of fact about Dr. Ayyadurai which Defendants knew to be false at the time the March 2012 Article was written and published.

26. The false statements of fact in the March 2012 Article include, among others:

a) Dr. Ayyadurai engaged in “tricks, falsehoods, and a misinformation campaign.”

b) Dr. Ayyadurai is engaged in “revisionism” with respect to his claims of invention of email.

27. On or about September 8, 2014, Defendants published on Gawker.com (another website owned and operated by Gawker) a story authored by Sam Biddle with the headline: “If Fran Drescher Read Gizmodo She Would Not Have Married This Fraud” (the “2014 Article”), a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit C. The story, from the outset in the title, falsely states that Dr. Ayyadurai is a “fraud,” and also states that he is a “renowned liar who pretends he invented email” and a “fake.”

28. The forgoing false statements of fact were made by Defendants with the knowledge that they were false and likely to harm Dr. Ayyadurai’s personal and professional reputation and business. The false and libelous statements in the February 2012 Article and the March 2012 Article (together, the “2012 Articles”), along with those in the 2014 Article, had the foreseeable effect of severely harming Dr. Ayyadurai’s personal and professional reputation and business.

29. In or about 2009, Dr. Ayyadurai entered into a contract with MIT as a lecturer. His position automatically renewed annually. In or about 2012, Dr. Ayyadurai’s lectureship was rescinded for the 2012-2013 school year. This was the first time his contract did not renew after he had lectured at MIT for three years.

30. In or about 2012, Dr. Ayyadurai was asked by MIT professors not to speak about email at an MIT Communications Forum in March 2012, which Dr. Ayyadurai had organized.

31. In or around the time, Dr. Ayyadurai was running one of the most popular elective courses at MIT called Systems Visualization; was in the midst of garnering contracts for his research center; and was the Director of a new initiative at MIT. After Defendants posted the 2012 Articles, MIT disavowed its relationship with the MIT EMAIL LAB; cancelled Dr. Ayyadurai’s class and revoked its support for his new initiative; and funders disappeared and reneged on their contracts, citing the negative press and its impact on their brand through their affiliation with Dr. Ayyadurai.

32. On or about February 16, 2012, The Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. had acquired documentation, including computer code and copyright information from Dr. Ayyadurai to profile his work in inventing email. The display was set to launch later in 2012, but was cancelled without explanation after Defendants’ publication of the 2012 Articles.

33. Dr. Ayyadurai lost numerous other opportunities in and after 2014, following Defendants’ publication of the 2014 Article.

34. Defendants knew that, by publishing the 2012 Articles and the 2014 Article, other media publications would publish similar stories, and repeat Defendants’ statements in the 2012 Articles and the 2014 Article. Numerous publications did in fact publish similar stories, citing to Defendants’ (false) statements in the 2012 Articles and the 2014 Article which called into question Dr. Ayyadurai’s invention and his overall character. These other publications included, among others: an October 17, 2013 article in Business Insider titled “Fran Drescher Is Dating The Guy Who Says He Invented Email”, and a March 5, 2012 article in The Verge titled “Exposing the self-proclaimed ‘inventor of email’”.

35. Prior to the publication of the 2012 Articles, Dr. Ayyadurai was an avid speaker at events around the world. With Defendants’ publication of the 2012 Articles and the 2014 Article, Dr. Ayyadurai has been deliberately attacked as an inventor and a scientist, and has lost numerous paid speaking engagements and lectureships. The articles also have negatively and significantly affected his ability to purse new opportunities and acquire investment for his new inventions—an important source of his livelihood as an inventor and entrepreneur. GAWKER’S WRONGFUL CONDUCT GENERALLY36. Plaintiff contends that actual malice is not required to be shown to prove the claims herein. However, in the event that actual malice were to be determined to be a requirement, the allegations in this Complaint, including the allegations below, demonstrate actual malice. Moreover, discovery has not yet commenced and Plaintiff expects to obtain through discovery additional evidence that would support actual malice.

37. Gawker is a company that routinely engages in wrongful conduct, and specifically, writes and publishes false and defamatory statements about people, invades people’s privacy and other rights, and publishes content that is irresponsible and that no other legitimate publication will publish.38. Gawker has been sued multiple times for defamation, including currently in an action in New York State Court, by the Daily Mail newspaper, and in an action in California by an individual named Charles Johnson, for writing and publishing false and unsubstantiated rumors that Mr. Johnson had been involved in misconduct and criminal activity.

39. Gawker also has been sued repeatedly for invading the privacy of others. Gawker recently lost a case filed by Terry Bollea, professionally known as “Hulk Hogan,” for publishing an illegal, secretly recorded video showing the wrestler naked and having consensual sexual relations in a private bedroom. In March 2016, a Florida jury awarded Hulk Hogan $115 million in compensatory damages plus $15 million, $10 million and $100,000, respectively, in punitive damages against Gawker, Denton and former editor, A.J. Daulerio.

40. Gawker also was sued by, and paid a substantial settlement to, actress Rebecca Gayheart and her husband, actor Eric Dane, for publishing a stolen private video of them partially nude in a hot tub.

41. Gawker has also been sued for copyright infringement, including by Dr. Phil’s production company after Gawker planned to “steal,” and eventually aired, portions of an interview before it aired on Dr. Phil’s television show.

42. Gawker also published a video of a clearly intoxicated young woman engaged in sexual activity on the men’s bathroom floor of an Indiana sports bar (the footage was taken by another patron with his mobile phone). According to published reports, Gawker callously refused to remove the footage from its site for some time, despite repeated pleas from the woman and despite the fact that it was not clear if the sex was consensual or if the video was footage of a rape in progress.

43. Gawker paid a source for a photograph of what the source claimed was NFL quarterback Brett Favre’s penis. Gawker published the uncensored photo and reported that it showed Mr. Favre’s penis.

44. Gawker published photos of Duchess Kate Middleton’s bare breasts, captured by a paparazzi’s telephoto lens while she was sunbathing in a secluded, private location.

45. Gawker published complete, uncensored, and unedited videos of seven innocent individuals being beheaded by ISIS soldiers. The videos were distributed by ISIS for the purpose of terrorizing the Western world. On information and belief, Gawker was the only established media company to publish these videos in full and uncensored, showing the victims being beheaded. Gawker was criticized severely by the press and terrorism experts for furthering the terror campaign of ISIS, and showing a total lack of regard for the families of these victims.

46. Gawker hacked a promotional campaign sponsored by Coca-Cola, in which the company utilized the hashtag “#MakeItHappy.” The campaign was originally designed to allow people to type statements into a decoder, and the decoder converted the statements into positive, happy statements. Gawker’s hack caused the campaign to publish highly offensive statements from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Gawker was resoundingly criticized throughout the media for its actions.

47. Gawker attempted to publicly “out”

a private male individual, who is a media executive at a rival publishing company, by publishing a story alleging that the executive had attempted to solicit a male porn star and prostitute. Gawker’s actions in publishing these allegations, including identifying the executive by name and the company he worked for, publishing the accusations of the gay porn star, and protecting the identity of the porn star “source,” were severely criticized throughout the media industry. As a result, multiple major advertisers began to pull their advertising from Gawker; Gawker then removed the story; and a few days later two senior executives at Gawker promptly resigned their positions. Following these events, several more executives and employees resigned or were terminated.

48. In the past year, seven of the nine most senior executives at Gawker and Gawker.com resigned: Chief Operating Officer Scott Kidder, Chief Strategy Officer Erin Pettigrew, Chief Technology Officer Tom Plunkett, Editorial Chief Tommy Craggs, President of Advertising Andrew Gorenstein, SVP of Global Sales and Partnerships Michael Kuntz and Editor-in-Chief of Gawker.com Max Reid. Of the original Executive Board from one year ago, only CEO/Founder Denton and General Counsel Heather Dietrick remain at the company. (Gawker had no CFO during this time.)

49. In November 2015, former Gawker staff writer, Dayna Evans, published an article titled: “On Gawker’s Problem With Women” (“the Evans Article”) in which Evans exposes gender inequalities within the company as well as an endemic of reporting failures and failures of journalistic ethics. The Evans Article states that the company’s reporting tactics “can lead to dismissiveness and insensitivity, harm and marginalization, often unforgettable and unforgivable damage.” The Evans Article further states that writers and editors at the company “are in fact REWARDED and admired for their recklessness and immaturity, a recklessness and immaturity, that, as you know, has gotten the company in heaps of trouble over the past couple of years.” The Evans Article goes on to state that the above assertions are true, “especially so at a place like Gawker, where bylines are associated with traffic and traffic is associated with success.”

SAM BIDDLE’S WRONGFUL CONDUCT GENERALLY50. In or about 2010, Gawker and Denton hired Biddle as a writer for Gawker’s technology focused website, Gizmodo.com. Biddle was subsequently promoted to editor at Gawker.com.

51. Biddle’s professed goal is to destroy people’s reputations and lives on the Internet, under the banner of journalism. In 2010, Biddle wrote: “Is it petty to not share in the happiness of someone else’s success? Is it petty to wish—to beg, even, knuckles blistering, eyes bloodshot, beseeching each god—for their horrific downfall.” Biddle reinforced this philosophy in April 2014 when he stated that he would “like to have a 20-to-1 ratio of ruining people’s days versus making them” and that he writes the types of articles he does because “I like attention.”52.

In 2013, Biddle published at Gawker a tweet sent out by a private media executive which contained a joke made in bad taste. Biddle’s sharing of the tweet caused the executive to lose her job and be subject to widespread scorn and ridicule. Biddle admitted that his publication of the tweet caused “an incredibly disproportionate personal disaster” for the executive.

53. Also in 2013, Biddle wrote a post at Gawker that took the comments of a venture capitalist out of context and made implicit accusations of racism.

54. In March 2014, Biddle sanctioned an article by a junior writer which compared a dating website to WWII Comfort Women. The article received severe criticism throughout the national media.

55. In October 2014, during National Bullying Prevention Month, Biddle sent out distasteful tweets through his Twitter account that supported bullying, stating: “Nerds should be constantly shamed and degraded into submission” and that society should “Bring Back Bullying.” The tweets and fallout that ensued caused several companies to withdraw advertising from Gawker. Gawker executives admitted that Biddle’s tweets, and the lost advertisers that followed, cost Gawker at least $1 million in advertising revenue.

56. In late 2015, Biddle wrote an article about his use and abuse of narcotics, including his substantial consumption of benzodiazepines, anti-depressants and SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Biddle’s drug abuse was well-known at Gawker, including by Denton and Cook, and they nevertheless continued to employ Biddle, promote him, reward him, and assign him to write articles about people.GAWKER’S PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICES57. Defendants have shown little interest in reporting the truth to the public, or investigating the facts underlying a story, or for that matter telling the truth to its readers. Defendants routinely make up lies about the subjects of their stories—Dr. Ayyadurai being one of many—with little or no regard to the substantial consequences that their false statements have on the subjects of their stories. The impact is serious and real. Defendants destroy personal and professional reputations and careers as a matter of routine.

58. In or about June 2009, Denton was interviewed by The Washington Post, and told the reporter: “We don't seek to do good. We may inadvertently do good. We may inadvertently commit journalism. [Spoken as if it were a crime.] That is not the institutional intention.” (emphasis added).59. Gawker’s philosophy and practice is to publish false scandal, for the purpose of profit, knowing that false scandal drives readership, which in turn drives revenue, and without regard to the innocent subjects of their stories whose careers are destroyed in the process.

60. This is the situation here: Defendants’ false statements in the articles at issue had the effect of so severely discrediting Dr. Ayyadurai—based on the false statement that he is a “fraud”—that Dr. Ayyadurai’s career was severely damaged. As a direct result of Defendants’ publication of the false and defamatory statements about Dr. Ayyadurai, on information and belief, Dr. Ayyadurai has lost teaching positions at MIT, lost several paid speaking engagements at the time and in the future, lost an accolade and display dedicated to his invention at the Smithsonian Institute, lost contracts and renewals, lost opportunities for investment in his emerging companies, suffered substantial personal and professional reputational harm, and suffered substantial harm to his career, business and income.

61. According to Gawker.com and Gizmodo.com, more than 195,100 people have read the 2014 Article that Defendants wrote and published; more than 87,900 people have read the February 2012 Article that Defendants wrote and published; more than 215,100 people have read the March 2012 Article that Defendants wrote and published; and presumably all of those readers have spoken to others about the stories. Moreover, the 2014 Article embeds the March 2012 Article directly in the center of the 2014 Article, summarizes it, and includes a hyperlink to the March 2012 Article, with a prominent display of the title of the March 2012 article along with a photo of Dr. Ayyadurai, and urges readers to read it. The March 2012 Article embeds the February 2012 Article directly in its center and includes a hyperlink to the February 2012 Article. Further, when the 2012 Articles were embedded into the 2014 Article, they were directed to a different audience and readership: readers of Gawker.com, versus readers of Gizmodo.com. Therefore, in September 2014, Defendants republished the 2012 Articles, originally published on Gizmodo.com, by directing them to a new audience of Gawker.com readers and multiplying the damage done to Dr. Ayyadurai.

62. As a result of Defendants’ wrongful actions, anyone who searches Dr. Ayyadurai at Google or other search engine will see Defendants’ false and libelous stories about him in the first page of search results across the world. As a result, anyone who would otherwise have hired or partnered with Dr. Ayyadurai likely will decline, and have declined, to do so, believing Defendants’ false and libelous statements about him to be true. These statements also resulted in a wave of efforts by others to discredit Dr. Ayyadurai and erase him from the history of electronic communications such as Walter Isaacson’s book on Internet pioneers, The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution; attacks on Wikipedia that remove reference to his contributions, and discrediting his other ongoing scientific contributions unrelated to email technology. Defendants’ actions foreseeably caused such results.63. Defendants are guilty of intentional misconduct. Defendants had actual knowledge of the wrongfulness of the conduct described herein and the high probability that injury or damage to Plaintiff would result and, despite that knowledge, intentionally pursued that course of conduct, resulting in substantial injury and damage to Dr. Ayyadurai.

64. Defendants’ conduct was so reckless or wanting in care that it constituted a conscious disregard or indifference to Dr. Ayyadurai’s rights.

65. Defendants’ actions described herein also have had the foreseeable effect of causing severe emotional distress to Dr. Ayyadurai, and did cause him to suffer severe emotional distress.

66. In 2014, Defendants continued their wrongful actions of 2012 when they published the defamatory 2014 Article about Dr. Ayyadurai, and linked Gawker.com readers to the March 2012 Article, which again linked to the February 2012 Article.

67. Dr. Ayyadurai requests herein all available legal and equitable remedies, to the maximum extent permissible by law, including without limitation compensatory damages in an amount not less than Thirty-Five Million Dollars ($35,000,000), and punitive damages.

FIRST CAUSE OF ACTION

Libel

(Against All Defendants Except Denton)68. Plaintiff hereby repeats and realleges each and every allegation set forth in paragraphs 1 through 67 of this Complaint as if fully set forth herein.

69. As described herein, the February 2012 Article arises to the level of defamation per se, in that it falsely states that “[Dr.] Ayyadurai is a fraud.”

70. As described herein, the March 2012 Article falsely alleges that:

a) Dr. Ayyadurai engaged in “semantic tricks, falsehoods, and a misinformation campaign.”

b) Dr. Ayyadurai is engaged in “revisionism” in his claim of invention of email.

71. As described herein, the 2014 Article arises to the level of defamation per se, by stating that Dr. Ayyadurai is a “fraud,” thus falsely accusing Dr. Ayyadurai of a crime and causing prejudice to his personal and professional reputation and business.

72. The 2014 Article also falsely states:

a) Dr. Ayyadurai is a “renowned liar” with respect to his statements that he invented email,

b) Dr. Ayyadurai is a “big fake,” and

c) Dr. Ayyadurai is engaged in “cyber-lies.”

73. These false statements wrongly accuse Dr. Ayyadurai of having made statements and acted in a manner that would subject him to hatred, distrust, contempt, aversion, ridicule and disgrace in the minds of a substantial number in the community, and were calculated to harm his social and business relationships, and did harm his social and business relationships.

74. The statements made intentionally, purposefully and with actual malice by Defendants were false and no applicable privilege or authorization protecting the statements can attach to them.

75. Plaintiff has been seriously damaged as a direct and proximate cause of the falsity of the statements made by Defendants in an amount to be determined at trial. The false statements attribute conduct, characteristics and conditions incompatible with the proper exercise of Plaintiff’s business and duties as an inventor, scientist and entrepreneur. Because the statements were widely disseminated on the Internet, they were also likely and intended to hold the Plaintiff up to ridicule and to damage his social and business relationships.

76. The above-quoted published statements constitute egregious conduct constituting moral turpitude. As such, in addition to compensatory damages and/or presumed damages, Plaintiff demands punitive damages relating to Defendants’ making of the above-quoted defamatory statements, in an amount to be determined at trial.SECOND CAUSE OF ACTION

Intentional Interference with Prospective Economic Advantage

(Against All Defendants Except Denton)77. Plaintiff hereby repeats and realleges each and every allegation set forth in paragraphs 1 through 76 of this Complaint as if fully set forth herein.

78. Defendants knew that Plaintiff, being an MIT professor/lecturer, scientist, inventor, business owner and entrepreneur, had business relationships that were ongoing during the time of Defendants’ publications, and had a reasonable expectation of entering into valid business relationships with additional individuals and entities, including with companies and universities, which would have been completed had it not been for Defendants’ wrongful acts.

79. Defendants acted solely out of malice and/or used dishonest, unfair or improper means to interfere with Plaintiff’s actual and prospective business relationships, before they defamed him.

80. Defendants, through the misconduct alleged herein, intended to harm Plaintiff by intentionally and unjustifiably interfering with his actual and prospective business relationships.

81. Defendants have seriously damaged Plaintiff’s actual and prospective business relationships as a direct and proximate cause of these acts.

82. The above-described conduct is egregious and constitutes moral turpitude. As such, in addition to compensatory damages and/or presumed damages, Plaintiff demands punitive damages in an amount to be determined at trial.

THIRD CAUSE OF ACTION

Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

(Against All Defendants Except Denton)83. Plaintiff hereby repeats and realleges each and every allegation set forth in paragraphs 1 through 82 of this Complaint as if fully set forth herein.

84. Defendants intentionally wrote the 2012 Articles and posted them to the Gizmodo.com website, and again intentionally wrote and published the 2014 Article to the Gawker.com website to humiliate, defame and embarrass Dr. Ayyadurai.

85. Defendants’ posting of the articles was extreme and outrageous in that the contents falsely accuse him of being a fraud and lying about his professional accomplishments and career.

86. Dr. Ayyadurai has suffered severe emotional distress as a result of the content written in the articles and the ramifications the false content has had on his personal life and professional reputation have been immense.

87. The above-described conduct is egregious and constitutes moral turpitude. As such, in addition to compensatory damages and/or presumed damages, Plaintiff demands punitive damages in an amount to be determined at trial.

FOURTH CAUSE OF ACTION

Negligent Hiring and Retention

(Against Denton and Cook)88. Plaintiff hereby repeats and realleges each and every allegation set forth in paragraphs 1 through 87 of this Complaint as if fully set forth herein.

89. At all times relevant to the allegations herein, Biddle was engaged in the abuse of multiple drugs including benzodiazepines, anti-depressants and SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), while employed at Gawker and particularly during the time that he wrote the 2014 Article.

90. At all relevant times, Denton and Cook knew or should have known of Biddle’s open and continuing abuse of such drugs, and the impact that it was having on his mental health, and the caustic and reckless articles that Biddle was writing about people as a result.

91. At all relevant times, Denton and Cook also knew or should have known that Biddle sought to libel and destroy the lives of the subjects of his reporting. In connection with Biddle’s reporting, Gawker and its executives, including Denton and Cook, received outcry and criticism about Biddle and his articles, while Biddle was employed with them.

92. Denton and Cook failed to take reasonable care in the hiring and/or retention of Biddle.

93. Denton and Cook placed Biddle in a position to cause foreseeable harm to others (including Dr. Ayyadurai) by placing Biddle and retaining him in the position of Senior Writer.

94. The above-described conduct is egregious and constitutes moral turpitude. As such, in addition to compensatory damages and/or presumed damages, Plaintiff demands punitive damages in an amount to be determined at trial.

DEMAND FOR JURY TRIALPlaintiff demands a trial by jury.

PRAYER FOR RELIEFWHEREFORE, Plaintiff Shiva Ayyadurai respectfully requests:

1. An award of damages to Plaintiff in an amount to be determined at trial, but in all events not less than Thirty-Five Million Dollars ($35,000,000);

2. An award of punitive damages to Plaintiff in an amount to be determined at trial;

3. An order requiring Defendants to make a public retraction of the false statements;

4. An order granting preliminary and permanent injunctive relief to prevent defendants from making further defamatory statements about Plaintiff; and

5. An award of such other and further relief as the Court may deem just and proper.

Dated: May 10, 2016

Respectfully submitted,

CORNELL DOLAN, P.C.

By: /s/ Timothy Cornell

Timothy Cornell, BBO # 654412

One International Place, Suite 1400

Boston, MA 02110

Tel: (617) 535-7763

Fax: (617) 535-7721

[email protected] HARDER MIRELL & ABRAMS LLP

By: /s/ Charles J. Harder

Charles J. Harder, Esq.

(Pro Hac Vice application to be filed)

132 S. Rodeo Drive, Suite 301

Beverly Hills, California 90212

Tel. (424) 203-1600

Email:

[email protected]Counsel for Plaintiff

_______________

Notes:1 “Email” as defined by Merriam-Webster Dictionary. The Online Etymology Dictionary lists “email” as entering the language in 1982, when Dr. Ayyadurai’s Copyright was registered.

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=e-mail