James Woods vs. John Doe: Reply in Support of Motion for An Order Compelling Non-Party Kenneth P. White to Answer Deposition Questions and Produce Documents; and an Order for Sanctions Against Non-Party Kenneth P. White in the Amount of $9,040.55

by James Woods

December 21, 2016

MICHAEL E. WEINSTEN (BAR NO. 155680)

LINDSAY MOLNAR, ESQ (BAR NO. 272156)

LAVELY & SINGER

PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION

2049 Century Park East, Suite 2400

Los Angeles, California 90067-2906

Telephone: (310) 556-3501

Facsimile: (310) 556-3615

Email: [email protected]

[email protected]

Attorneys for Plaintiff JAMES WOODS

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES

JAMES WOODS, an individual,

Plaintiff,

vs.

JOHN DOE a/k/a "Abe List" and DOES 2

through 10, inclusive,

Defendants.

Case No.: BC 589746

[Hon. Mel Recana, Dept. 45]

REPLY IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR: (1) AN ORDER COMPELLING NON-PARTY KENNETH P. WHITE TO ANSWER DEPOSITION QUESTIONS AND PRODUCE DOCUMENTS; AND (2) AN ORDER FOR SANCTIONS AGAINST NON-PARTY KENNETH P. WHITE IN THE AMOUNT OF $9,040.55

Date: January 3, 2017

Time: 8:35 a.m.

Dept: 45

Reservation ID: 161109172908

Complaint Filed: July 29, 2015

Trial Date: None

I. INTRODUCTION

At the outset, White's [1] Opposition to Woods' Motion not only lacks merit under California law, but actually demonstrates precisely why White must be ordered to disclose the information at issue concerning the identity of his client, AL. Most significantly, White actually admits in his Opposition that the reason he seeks to protect AL's identity is because "[r]evealing his identity would subject [AL] to civil liability by revealing that he was the one who posted the tweet that [Woods] sued over." See Opposition at 8: 1 7-19. In other words, White is taking the position that AL should be allowed to remain anonymous in order to avoid liability for Woods' claims in this action - claims that this Court has already acknowledged (in denying AL's anti-SLAPP motion) have a likelihood of success. Obviously, a party to a lawsuit cannot remain anonymous simply to avoid liability in that lawsuit. [2] If such was the case, then potential defamers would be encouraged and granted free license to make malicious and defamatory statements under the guise of anonymity, knowing that litigation against them would be an illusory and ineffective exercise. By taking such an outrageous and absurd position in support of withholding AL's identity, White has demonstrated the true impropriety of his intent here -- an impropriety that taints the credibility of White's entire Opposition.

The impropriety of White's intent is further evidenced by his deceptive attempt to mischaracterize the record in this case -- including with respect to alleged "harassment" by Woods. For example, while White boldly accuses Woods' counsel of a purported intent to publicly release his deposition video (Opposition at 6:6-10), he provides no evidence to support this accusation. To the contrary, White's own cited deposition excerpts merely reflect that Woods' counsel was not prepared to agree at his deposition to a confidentiality stipulation, but was open to discussing the issue further, including through the entry of a protective order. See Depo at 45:1-46:3. Similarly, despite White's incendiary contention that Woods' "aim" is to harass AL's relatives (Opposition at 2:16-20), he provides no evidence whatsoever to suggest that Woods ever expressed any animus towards those relatives. Moreover, while White spends significant portions of his Opposition attempting to portray Woods as the aggressor in this case, the simple fact remains that White's own client, AL, was the party who initiated this dispute by posting a series of malicious tweets about Woods on Twitter -- referring to Woods on as a "joke," a "clown-boy," "ridiculous," and "scum" -- culminating in AL's false and defamatory statement that Woods was a "cocaine addict." [3] White's deceptive tactics should not be countenanced by the Court.

It further bears noting that, despite premising his entire Opposition on the notion that AL is deceased, White has still failed to set forth any admissible evidence actually supporting this "fact." Without such evidence, how is Woods (or the Court, for that matter) to even know that AL has not lied about his own death - especially given AL's documented propensity for lying? Indeed, White himself admits in his declaration that "most of the information" in AL's twitter profile was completely ''fictional.'' See White Declaration, Para 5. Moreover, White previously admitted in his deposition that he never even saw AL's alleged death certificate. See Depo at 16:13-15 ("I have not reviewed a death certificate of Abe List."). In light of such admissions by White, it is all the more critical that Woods obtain proof of AL's identity.

As set forth in detail below, White has effectively conceded in his Opposition (including through his own cited cases) that neither the attorney client privilege nor the right of privacy allows him to withhold the critically relevant identifying information about AL that Woods seeks. Indeed, even if the attorney-client privilege did apply, it would have been waived long ago by AL when he authorized White to disclose a significant part of his communications concerning his identity. Moreover, to the extent that White claims Woods intends to harass AL's relatives, White has failed to provide any evidence supporting this claim (and the evidence that he does provide actually cuts against any notion of harassment).

Accordingly, in the absence of any cognizable counter-arguments by White, there is no reason why the Court should not compel White to answer the deposition questions set forth in Woods' Separate Statement, as well as produce the documents responsive to Woods' Subpoena. Moreover, based on the untenable and outlandish positions taken by White in his Opposition (which plainly show that White did not act with "substantial justification" in refusing to answer the discovery at issue), there is no reason why the Court should not award monetary sanctions against White and in favor of Woods in the sum of $9,040.55.

II. WHITE HAS EFFECTIVELY ADMITTED THAT AL'S IDENTIFYING INFORMATION IS NOT PROTECTED BY THE ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE.

In his Motion, Woods clearly demonstrated that the facts concerning AL's identity (such as AL's name, age, and the identity of his personal representative) are not and cannot be attorney-client privileged. Indeed, not only are these facts, not communications, but there is nothing confidential about them (given that AL's identity is known by many people outside the scope of any attorney-client relationship).

In his Opposition, White effectively admits that AL's identifying information does not fall within the purview of the attorney-client privilege. Most notably, while White primarily cites to and discusses the Willis v. Superior Court case, that case actually held that the names of the attorney's clients at issue were discoverable because (as is the case here) such information was "directly relevant to the issues in dispute." 112 Cal.App.3d 277,294 (1980). The parties in that case (both attorneys) were each claiming that they had stolen one another's clients, and thus the court found that the identification of those clients was a necessary component of proving the claims. Here, similarly, AL' s identity is critical and relevant to Woods' ability to investigate and gather information to prosecute his claims against AL. Indeed, in light of the fact that White has refused to provide any evidence corroborating his claim that AL is deceased, the disclosure of AL's identity is necessary in order for Woods to confirm whether AL actually died. Thus, the Willis case -- White's primary authority in on the issue of attorney-client privilege -- actually supports Woods' position.

Moreover, to the extent that White attempts to avail himself of the extremely limited exceptions to the general rule that client identities are not privileged, his argument is, quite frankly, absurd. In particular, the thrust of White's argument on this point is that he should be allowed to withhold AL's identity simply because "revealing [AL's] identity would subject [AL] to civil liability by revealing that he was the one who posted the tweet that Mr. Woods sued over." See Opposition at 8:17-19. In other words, White is taking the outlandish position that he cannot reveal AL's name because the reveal would allow Woods to hold AL liable for the conduct alleged in Woods' complaint. Of course, if this was the law, then potential defamers would be encouraged and granted free license to make malicious and defamatory statements under the guise of anonymity, knowing that litigation against them would be an illusory exercise. Such a result would obviously run counter to both law and common sense. Indeed, it bears noting that none of White's cited authorities support his supposed position -- nor is Woods aware of even a single case where a court allowed an attorney of a party in litigation to withhold the identity of his client on privilege grounds. Rather, a client's identity may only be withheld in the limited circumstances where the disclosure would subject the client to harm separate and apart from any liability for the claims at issue in a pending lawsuit. See, e.g., Baird v. Koerner, 279 F.2d 623, 630 (1960) (disclosing the names of an attorney's clients -- who were not parties to the litigation -- would subject those clients to liability for unpaid taxes).

Notably, while White cites to the Mitchell v. Superior Court case in order to argue that the "facts" concerning AL's identity are in and of themselves privileged on account of being relayed to White during an attorney-client conversation, Mitchell does not stand for such a misguided proposition. Rather, Mitchell merely held that certain facts provided by an attorney to his client were considered privileged because they comprised the very legal advice that was provided by the attorney. See Mitchell, 37 Cal. 3d 591, 589-601 (1984). Here, in stark contrast, the identifying information at issue would have been provided by AL to White (not vice versa as was the case in Mitchell), and therefore could not constitute legal advice in and of itself. In other words, Mitchell is completely inapposite here.

In any event, even assuming that the facts concerning AL' s identifying information were initially privileged, that privilege was waived by AL when he authorized White to disclose "personal information about him" to Woods, including the material facts that: (1) "most of the information in the profile of his Twitter account [was] fictional," (2) he "was not married," (3) he "did not own a house in Los Angeles," (4) he "was not employed at the time the lawsuit was filed," (5) he "did not work in finance or math and was not a partner in private equity," and (6) he "did not have assets to satisfy Mr. Woods even if Mr. Woods won [this case]" See Opposition at 13:23-14:13; White Declaration, para. 5. AL's personal representative similarly waived the attorney-client privilege by authorizing White to disclose the material facts that: (1) "the estate would no longer defend the case," (2) "the estate lacked assets sufficient to satisfy any significant judgment," and (3) "that several of Mr. Woods' beliefs about [AL] (for instance, the belief he was married) were untrue and based on a fictional Twitter profile." White Declaration, para. 7. As a matter of law (and fairness), AL (and/or his personal representative) simply cannot turn the attorney-client privilege on and off to suit his particular needs. Rather, California law is clear that a party cannot disclose only those privileged facts beneficial to its case (in this instance, the facts that would support AL's purported inability to satisfy a judgment) and refuse to disclose, on the grounds of privilege, related facts detrimental to his position (in this instance, those facts that would allow Woods to obtain and collect a judgment against AL). See Merritt v. Superior Court, 9 Cal. App. 3d 721, 731 (1970) (when the privilege holder's "conduct touches a certain point of disclosure, fairness requires that his privilege shall cease whether he intended that result or not. He cannot be allowed, after disclosing as much as he pleases, to withhold the remainder.") (citing to Wigmore on Evidence, McNaughton Revision, Volume VIII, section 2327); Kerns Construction Co. v. Superior Court, 266 Cal. App. 2d 405,414 (1968) (same). Fundamental to this analysis is the notion that a party should not be able to simply pick and choose which privilege communications it will disclose and which it will not. "He may elect to withhold or to disclose, but after a certain point his election must remain final." Merritt, supra, 9 Cal.App.3d at 731; see also Handgards, Inc. v. Johnson & Johnson, 413 F. Supp. 926, 929 (N.D. Cal. 1976) ("An important consideration in assessing the issue of waiver is fairness. Thus, a party may not insist on the protection of the attorney-client privilege for damaging communications while disclosing other selected communications because they are self-serving. Voluntary disclosure of part of a privileged communication is a waiver as to the remainder of the privileged communication about the same subject."); Weil v. Investment Indicators, 647 F. 2d 18, 24 (9th Cir. 1981) ("[I]t has been widely held that voluntary disclosure of the content of a privileged attorney communication constitutes waiver of the privilege as to all other such communications on the same subject."). In this case, by voluntarily allowing White to disclose a "significant part" of the communications concerning his identity, AL waived the privilege with respect to those communications. Cal. Evid. Code § 912 (a).

Finally, to the extent that White attempts to fault Woods for purportedly failing to ""exhaust[] other methods of discovering [AL's] identity," this argument is self-defeating in light of White's own admission that he opposed Woods' attempt to subpoena Twitter. See Opposition at 3:13-15, 8:27-28. Indeed, one of the very reasons that Twitter has refused to comply with the Subpoena is because of White's objection thereto. [4] As a matter of fairness, White cannot on the one hand oppose Woods' attempt to discover AL' s identity from third parties, and then on the other hand fault Woods for failing to obtain such third party discovery.

In sum, because White has failed to set forth any law or facts indicating that AL' s identifying information is within the scope of the attorney-client privilege, and because that privilege would have been waived in any event by AL, White has conceded Woods' point that the attorney-client privilege does prevent disclosure of the fundamental facts concerning AL' s identification.

III. WHITE HAS FURTHER CONCEDED THAT AL'S IDENTIFYING INFORMATION IS NOT PRIVATE INFORMATION.

As set forth in Woods' Motion, because the right of privacy does not survive death, and because White contends that AL is deceased, then (by White's own admission) AL no longer has any right to privacy. See Lugosi v. Universal Pictures, 25 Ca1.3d 813, 820, 833 (1979); Hendrickson v. California Newspapers, Inc., 48 Cal.App.3d 59, 62 (1975); Flynn v. Higham, 149 Cal.App.3d 677 (1983). Moreover, because of the public interest in an open court system, including the public's right to know the identity of parties to a lawsuit, AL never even had the right to proceed anonymously in the first place. See Doe v. Kamehameha Schools etc., 596 F.3d 1036, 1042-43 (9th Cir. 2010); United States v. Doe, 655 F .2d 920, 922 (9th Cir. 1980). Thus, to the extent White objected to the disclosure of information concerning AL's identity on privacy grounds, such objections have no merit.

White does not effectively dispute this notion in his Opposition. To the contrary, he actually admits that the Court (in denying AL's anti-SLAPP motion) already "rejected" his privacy argument as it pertains to AL. Opposition at 11: 15-17.

Moreover, while White attempts to dispute that AL's right to privacy died with him, his only cited authorities are wholly inapposite and have no bearing whatsoever on the facts at bar. Opposition at 11-12. Indeed, White's reliance on McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Comm'n, 514 U.S. 334 (1995) is actually deceptive, as the use of the term "anonymous" in that case had nothing to do with the plaintiffs identity as a litigant. To the contrary, the plaintiffs name, Margaret McIntyre, was disclosed from the inception of the case, and there was no argument that she was entitled to keep her identity as a litigant private. The only issue was whether she had the right, in the context of purely political speech, to distribute unsigned (i. e. "anonymous") political leaflets at school district meetings.

White's other cited authorities are similarly unsupportive of his position. For example, the court in Powell v. U.S. Dep't of Justice, 584 F. Supp. 1508, 1528 (N.D. Cal. 1984) actually found that the names of the deceased individuals should be disclosed. And the cases of National Archives & Records Administration v. Favish, 541 U.S. 157, 171 (2004) and Catsouras v. Dep't of California Highway Patrol, 181 Cal. App. 4th 856, 870 (2010) dealt with the completely distinguishable issue of whether family members have the right to prevent the disclosure of graphic photographs of their relative's death. Nevertheless, the court in Catsouras acknowledged that the right to privacy dies with an individual (but made a special exception in the limited and fact specific context of death photographs). Of course, Woods is not seeking to publish photos of AL's dead body.

Simply stated, and as evidenced by White's own admission and cited authorities, White cannot in good faith claim that the identity of AL is protected by the right of privacy. Thus, White has conceded Woods' point on this issue.

IV. WHITE HAS FAILED TO SHOW ANY COGNIZABLE HARASSMENT BY WOODS THAT WOULD MERIT THE WITHOLDING OF AL'S CRITICAL IDENTIFYING INFORMATION.

Regarding the issue of alleged harassment by Woods, White's entire argument effectively boils down to the misguided notion that simply because Woods rejected White's purported offer to "disclose AL' s identity in settlement discussions if Mr. Woods would agree to keep it confidential," and simply because Woods has made some strongly-worded tweets about AL, Woods must necessarily be seeking to harass AL and/or AL's relatives. See Opposition at 10:18-24. Like White's other arguments, this argument lacks merit and is actually nonsensical in the context of this case.

First and foremost, with respect to White's purported settlement offer, any offer to disclose AL's identity on a purely confidential basis and in exchange for a mutual release of claims (which is all that White offered to do) would be completely illusory in the context of this action. More specifically, the very reason that Woods needs AL's identifying information is so he can effectively prosecute his claims against AL. Thus, the mere receipt by Woods of AL's identifying information, without the ability to actually use that information to pursue this case, would be completely pointless. [5] As such, Woods cannot be faulted for declining to accept this offer, and his refusal is in no way indicative of an intent to harass.

Moreover, to the extent that White is pointing to certain of Woods' strongly-worded tweets as evidence of Woods' intent to harass, this argument actually cuts against White insofar as AL is the party whose vitriolic and harassing tweets gave rise to this action in the first place. As set forth in Woods' Complaint, AL previously engaged his thousands of Twitter followers with a campaign of harassing and angry tweets directed towards Woods, calling Woods such derogatory names as "prick," "joke," "ridiculous," "scum" and "clown-boy." See Complaint, para. 8. Indeed, evidence of AL' s malicious and harassing tweets was already placed before the Court in support of Woods' successful opposition to AL's anti-SLAPP motion. Accordingly, if Woods responded to AL's harassment by using strong language, such conduct was purely defensive and justified by AL' s defamation. Stated otherwise, Woods' tweets do not evidence any "harassment" that would allow White to withhold AL' s identity.

Finally, White has provided no evidence whatsoever to suggest that Woods intends to harass AL' s relatives, or that Woods intends to use the information at issue for any other purpose than to prosecute his claims in this lawsuit. Thus, his arguments in this respect are completely unsubstantiated.

V. CONCLUSION

For all the reasons set forth above and in Woods' Motion and Separate Statement, Woods respectfully requests that the Court issue an Order directing White to appear and answer the questions set forth in Woods' Separate Statement and to produce all documents specified in the Subpoena at 10:00 a.m. on January 5, 2017. Woods also respectfully requests that the Court award monetary sanctions against White and in favor of Woods in the sum of $9,040.55.

Dated: December 21, 2016

LAVELY & SINGER

PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION

MICHAEL E. WEINSTEN

LINDSAY MOLNAR

By: MICHAEL E. WEINSTEN

Attorneys for Plaintiff JAMES WOODS

PROOF OF SERVICE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA, COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES

I am employed in the County of Los Angeles, State of California. I am over the age of 18 and not a party to the within action. My business address is 2049 Century Park East, Suite 2400, Los Angeles, California 90067-2906.

On the date indicated below, I served the foregoing document described as:

REPLY IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR: (1) AN ORDER COMPELLING NONPARTY KENNETH P. WHITE TO ANSWER DEPOSITION QUESTIONS AND PRODUCE DOCUMENTS; AND (2) AN ORDER FOR SANCTIONS AGAINST NONPARTY KENNETH P. WHITE IN THE AMOUNT OF $9,040.55

on the interested parties in this action by placing [ ] the original document OR [X] a true and correct copy thereof enclosed in sealed envelopes addressed as follows:

Kenneth P. White, Esq.

Brown White & Osborn LLP

11 333 S. Hope Street, 40th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90071-1406

12 Email: [email protected]

Tel: (213) 613-9446

Attorneys for John Doe (@abelisted)

[X] BY MAIL: I am "readily familiar" with the firm's practice of collection and processing correspondence for mailing. Under that practice it would be deposited with U.S. postal service on that same day with postage thereon fully prepaid at Los Angeles, California in the ordinary course of business. I am aware that on motion of the party served, service is presumed invalid if postal cancellation date or postage meter date is more than one day after date of deposit for mailing in affidavit.

[] BY PERSONAL SERVICE:

[] I caused such envelope to be delivered by a messenger employed by Express Network.

[ ] I delivered said envelope(s) to the offices of the addressee(s), via hand delivery.

[ ] BY ELECTRONIC SERVICE: I transmitted the foregoing document by electronic mail to the email addresses) stated on the service list per agreement in accordance with Code of Civil Procedures section 1010.6.

I declare under penalty of perjury under the laws of the State of California that the above is true and correct.

Executed December 21, 2016, at Los Angeles, California.

N. Echesabal

_______________

Notes:

1 Unless otherwise indicated, capitalized terms used herein have the same definitions as in Woods Motion.

2 Indeed, Woods is not aware of a single case where a court has allowed an attorney of a party to a lawsuit to withhold the identity of his client on privilege grounds, nor has White cited any such case in his Opposition.

3 White's tactic from the inception of this case has been to make false personal attacks against Woods which have nothing to do with the issues at hand, but which are obviously calculated to draw the Court's ire. By way of example, White previously made the false claim that his client's defamatory tweet was in response to a "homophobic" tweet by Woods, when in fact there was nothing at all in Woods' tweet that was disparaging to the GLBTQ community.

4 Based on White's own admission that "most of the information" in AL's twitter profile was completely "fictional," it is not even clear whether Twitter would have AL's actual identifying information. See White Declaration, para. 5.

5 For example, even assuming arguendo that Woods accepted White's offer, and White then disclosed AL's name, how would Woods know that White was telling the truth? Because Woods would have had to release his claims, he would be prevented from taking any discovery to verify whether White's information was in fact accurate. Such an outcome would be completely backwards and absurd.

Attorney Ordered to Identify Dead Client Who Taunted James W

18 posts

• Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Re: Attorney Ordered to Identify Dead Client Who Taunted Jam

Letter From Ryan T. Mrazik (Twitter Counsel) to Michael E. Weinsten (James Woods Counsel)

by Ryan T. Mrazik

August 21, 2015

PERKINSCOIE

1201 Third Avenue

Suite 4900

Seattle, WA 98101-3099

1.206.359.8000

1.206.359.9000

perkinscoie.com

Ryan T. Mrazik

[email protected]

D. (206) 359-8098

F. (206) 359-9098

August 21, 2015

VIA EMAIL AND OVERNIGHT MAIL

Michael E. Weinsten

Evan N. Spiegel

Lavely & Singer, P.C.

2049 Century Park East, Suite 2400

Los Angeles, California 90067-2906

Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Re: Subpoena to Nonparty Twitter, Inc., James Woods v. John Doe a/k/a "Abe List", et al., Case #BC589746 (Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles)

Dear Messrs. Weinsten and Spiegel:

We represent nonparty Twitter, Inc. ("Twitter") and write in response to your subpoena of August 4, 2015, seeking user identifying information and records, including the IP address, for a Twitter user account. For the reasons stated below, Twitter objects to your request. Please contact me directly to meet and confer if you disagree with any of our objections.

First, Twitter objects because you have provided no documentation showing that the Court considered and imposed the First Amendment safeguards required before a litigant may be permitted to unmask the identity of an anonymous speaker. As courts have recognized, a trial court must strike a balance "between the well-established First Amendment right to speak anonymously, and the right of the plaintiff to protects its proprietary interests and reputation through the assertion of recognizable claims based on the actionable conduct of the anonymous, fictitiously-named defendants." Dendrite Int'l, Inc. v. Doe No. 3,775 A.2d 756, 760 (N.J. Super. A.D. 2001). Accordingly, before a service provider such as Twitter may be compelled to unmask an anonymous speaker, (1) a reasonable attempt to notify the user of the request and the lawsuit must be made, and (2) the plaintiff must make a prima facie showing of the elements of defamation. See Krinsky v. Doe, 72 Cal. Rptr. 3d 231, 239, 244-46 (Cal. Ct. App. 2008). Moreover, under California law, the party seeking discovery must demonstrate "a compelling need for discovery" that "outweigh[s] the privacy right when these two competing interests are carefully balanced." Digital Music News LLC v. Superior court of Los Angeles, 226 Cal. App. 4th 216, 229 (2014) (citing Lantz v. Superior court, 28 Cal. App. 4th 1839, 1853-54 (1994).

It does not appear that you will be able to meet these standards. The speech at issue appears to be opinion and hyperbole rather than a statement of fact. Further, the target of the speech is a public figure who purposefully injects himself into public controversies, and there has been no showing of actual malice. Attempts to unmask anonymous online speakers in the absence of a prima facie defamation claim are improper and would chill the First Amendment rights of speakers who use Twitter's platform to express their thoughts and ideas instantly and publicly, without barriers.

Twitter next objects because the subpoena appears to constitute unauthorized early discovery under California law. CAL. CODE CIV. P. Section 2025.210(b). A defendant has not been served or appeared and it does not appear from the docket that the Court otherwise authorized early discovery. Please provide us with the rule or order that authorized issuance of the subpoena.

Further, all discovery requests must be calculated to lead to discovery of relevant and admissible evidence. CAL CODE CIV. P. Section 2017.010. Twitter therefore objects, for example, to your request for "[a]ny user records" and "all handle ... and associated user names ... used or otherwise associated at any time with the AbeListed Twitter Acct and/or its user(s)" as overly broad because it is unlimited in scope, and/or not related to an alleged injury or claim for recovery. See, e.g., Tompkins v. Detroit Metro. Airport, 278 F.R.D. 387, 388-89 (E.D. Mich. 2012) (denying request for content of online account and emphasizing that a litigant "does not have a generalized right to rummage at will through information that [another party] has limited from public view").

Twitter also objects to the subpoena because it is vague, overbroad, and unduly burdensome. For example, Twitter objects to the subpoena's requests for "[a]ny user records" or records "associated" with an account from "any time prior to the date of this request."

Finally, Twitter objects because your subpoena demands deposition testimony more than 75 miles from San Francisco or beyond the jurisdiction of the issuing court. See CAL CODE CIV. P. Section 2025.250(c)("[T]he deposition of [a non-party] shall be taken within 75 miles of the organization's principal executive or business office in California."); see also id. Section 2029.400 (Foreign subpoenas under the Interstate and International Depositions and Discovery Act must be personally served under the rules governing service of subpoenas in California actions.).

Twitter has provided notice to the email address associated with the Twitter account identified in your subpoena. Twitter understand that the user intends to challenge the subpoena and that Mr. Kenneth White of Brown, White & Osborn, LLP, will be contacting you soon. Twitter will take no further action until the user's objections are resolved by the Court. Even then, however, Twitter's objections would need to be addressed before Twitter produces any responsive records.

Please feel free to contact me if you would like to further discuss these objections. Twitter otherwise preserves and does not waive any other available objections or rights.

Very truly yours,

Ryan T. Mrazik

by Ryan T. Mrazik

August 21, 2015

PERKINSCOIE

1201 Third Avenue

Suite 4900

Seattle, WA 98101-3099

1.206.359.8000

1.206.359.9000

perkinscoie.com

Ryan T. Mrazik

[email protected]

D. (206) 359-8098

F. (206) 359-9098

August 21, 2015

VIA EMAIL AND OVERNIGHT MAIL

Michael E. Weinsten

Evan N. Spiegel

Lavely & Singer, P.C.

2049 Century Park East, Suite 2400

Los Angeles, California 90067-2906

Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Re: Subpoena to Nonparty Twitter, Inc., James Woods v. John Doe a/k/a "Abe List", et al., Case #BC589746 (Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles)

Dear Messrs. Weinsten and Spiegel:

We represent nonparty Twitter, Inc. ("Twitter") and write in response to your subpoena of August 4, 2015, seeking user identifying information and records, including the IP address, for a Twitter user account. For the reasons stated below, Twitter objects to your request. Please contact me directly to meet and confer if you disagree with any of our objections.

First, Twitter objects because you have provided no documentation showing that the Court considered and imposed the First Amendment safeguards required before a litigant may be permitted to unmask the identity of an anonymous speaker. As courts have recognized, a trial court must strike a balance "between the well-established First Amendment right to speak anonymously, and the right of the plaintiff to protects its proprietary interests and reputation through the assertion of recognizable claims based on the actionable conduct of the anonymous, fictitiously-named defendants." Dendrite Int'l, Inc. v. Doe No. 3,775 A.2d 756, 760 (N.J. Super. A.D. 2001). Accordingly, before a service provider such as Twitter may be compelled to unmask an anonymous speaker, (1) a reasonable attempt to notify the user of the request and the lawsuit must be made, and (2) the plaintiff must make a prima facie showing of the elements of defamation. See Krinsky v. Doe, 72 Cal. Rptr. 3d 231, 239, 244-46 (Cal. Ct. App. 2008). Moreover, under California law, the party seeking discovery must demonstrate "a compelling need for discovery" that "outweigh[s] the privacy right when these two competing interests are carefully balanced." Digital Music News LLC v. Superior court of Los Angeles, 226 Cal. App. 4th 216, 229 (2014) (citing Lantz v. Superior court, 28 Cal. App. 4th 1839, 1853-54 (1994).

It does not appear that you will be able to meet these standards. The speech at issue appears to be opinion and hyperbole rather than a statement of fact. Further, the target of the speech is a public figure who purposefully injects himself into public controversies, and there has been no showing of actual malice. Attempts to unmask anonymous online speakers in the absence of a prima facie defamation claim are improper and would chill the First Amendment rights of speakers who use Twitter's platform to express their thoughts and ideas instantly and publicly, without barriers.

Twitter next objects because the subpoena appears to constitute unauthorized early discovery under California law. CAL. CODE CIV. P. Section 2025.210(b). A defendant has not been served or appeared and it does not appear from the docket that the Court otherwise authorized early discovery. Please provide us with the rule or order that authorized issuance of the subpoena.

Further, all discovery requests must be calculated to lead to discovery of relevant and admissible evidence. CAL CODE CIV. P. Section 2017.010. Twitter therefore objects, for example, to your request for "[a]ny user records" and "all handle ... and associated user names ... used or otherwise associated at any time with the AbeListed Twitter Acct and/or its user(s)" as overly broad because it is unlimited in scope, and/or not related to an alleged injury or claim for recovery. See, e.g., Tompkins v. Detroit Metro. Airport, 278 F.R.D. 387, 388-89 (E.D. Mich. 2012) (denying request for content of online account and emphasizing that a litigant "does not have a generalized right to rummage at will through information that [another party] has limited from public view").

Twitter also objects to the subpoena because it is vague, overbroad, and unduly burdensome. For example, Twitter objects to the subpoena's requests for "[a]ny user records" or records "associated" with an account from "any time prior to the date of this request."

Finally, Twitter objects because your subpoena demands deposition testimony more than 75 miles from San Francisco or beyond the jurisdiction of the issuing court. See CAL CODE CIV. P. Section 2025.250(c)("[T]he deposition of [a non-party] shall be taken within 75 miles of the organization's principal executive or business office in California."); see also id. Section 2029.400 (Foreign subpoenas under the Interstate and International Depositions and Discovery Act must be personally served under the rules governing service of subpoenas in California actions.).

Twitter has provided notice to the email address associated with the Twitter account identified in your subpoena. Twitter understand that the user intends to challenge the subpoena and that Mr. Kenneth White of Brown, White & Osborn, LLP, will be contacting you soon. Twitter will take no further action until the user's objections are resolved by the Court. Even then, however, Twitter's objections would need to be addressed before Twitter produces any responsive records.

Please feel free to contact me if you would like to further discuss these objections. Twitter otherwise preserves and does not waive any other available objections or rights.

Very truly yours,

Ryan T. Mrazik

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 37658

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Attorney Ordered to Identify Dead Client Who Taunted Jam

Deposition Subpoena for Production of Business Records (To Twitter)

by James Woods

November 9, 2016

DEPOSITION SUBPOENA FOR PRODUCTION OF BUSINESS RECORDS

To: Custodian of Records for Twitter, Inc.

1355 Market Street, Suite 900, San Francisco, CA 94103

JAMES WOODS v. JOHN DOE a/k/a "Abe List", et al.

Los Angeles Superior Court, Case No. BC589746

ATTACHMENT 3

DEPOSITION SUBPOENA FOR PRODUCTION OF BUSINESS RECORDS on Custodian of Records for TWITTER, INC.

I. Relevant Background and Reason for Information Request From Twitter:

On July 29, 2015, Plaintiff James Woods ("Woods") filed the above-entitled lawsuit which arose from the publication of a malicious and fabricated statement by an individual who hides behind the Twitter name "Abe List" and handle/user "@abelisted" ("AbeListed"). On July 15, 2015, AbeListed falsely accused actor James Woods of being a "cocaine addict" on the social media site Twitter, a message sent to thousands of AbeListed's followers and hundreds of thousands of Mr. Woods' followers. Woods is not now, nor has he ever been, a cocaine addict, and AbeListed had no reason to believe otherwise. AbeListed's reckless and malicious behavior, through the worldwide reach of the Internet, has now jeapardized Woods' good name and reputation on an international scale. The documents sought pursuant to this Subpoena are relevant and material to the trial of this case because Woods needs the documents in order to identify and prosecute his defamation and invasion of privacy claims against AbeListed.

II. The records to be produced pursuant to the Subpoena and this Attachment 3 are with reference to the following Twitter account and user profile ID:

1. twitter.com/abelisted

2. @abelisted

3. mobile.twitter.com/abelisted

Collectively referred to herein as the "AbeListed Twitter Acct."

III. The records to be produced pursuant to Subpoena and this Attachment "3" are as follows:

1. Account user information for the AbeListed Twitter Acct, including any documents or writings (the term "writings" in this request, and each subsequent request using the term, means as defined by California Evidence Code Section 250) evidencing the name, address, telephone number, e-mail address(es), IP address(es) and/or any other available contact and/or identifying information for the holder(s) of the AbeListed Twitter Acct, and/or associated with the AbeListed Twitter Acct, both concurrently and at any time prior to the date of this request.

2. Any user records, data and writings (or a copy of the information contained therein) which evidence and identify each IP address (including date and time of use of said IP address) associated with and/or used at any time by any person in relation to creating or modifying or posting to the AbeListed Twitter Acct.

3. Any user records, data and writings (or a copy of the information contained therein) which evidence and identify the IP address (including date and time of use of said IP address) used by the user who posted the Tweet/Comment "@RealJamesWoods @banshapiro cocaine addict James Woods still sniffing and spouting," dated July 15, 2015 7:40 AM, at URL http://twitter.com/abelisted/status/621328418861248512

4. A list of all handle (i.e., @names) and associated user names, in addition to the AbeListed handle, used or otherwise associated at any time with the AbeListed Twitter Acct and/or its user(s).

by James Woods

November 9, 2016

DEPOSITION SUBPOENA FOR PRODUCTION OF BUSINESS RECORDS

To: Custodian of Records for Twitter, Inc.

1355 Market Street, Suite 900, San Francisco, CA 94103

JAMES WOODS v. JOHN DOE a/k/a "Abe List", et al.

Los Angeles Superior Court, Case No. BC589746

ATTACHMENT 3

DEPOSITION SUBPOENA FOR PRODUCTION OF BUSINESS RECORDS on Custodian of Records for TWITTER, INC.

I. Relevant Background and Reason for Information Request From Twitter:

On July 29, 2015, Plaintiff James Woods ("Woods") filed the above-entitled lawsuit which arose from the publication of a malicious and fabricated statement by an individual who hides behind the Twitter name "Abe List" and handle/user "@abelisted" ("AbeListed"). On July 15, 2015, AbeListed falsely accused actor James Woods of being a "cocaine addict" on the social media site Twitter, a message sent to thousands of AbeListed's followers and hundreds of thousands of Mr. Woods' followers. Woods is not now, nor has he ever been, a cocaine addict, and AbeListed had no reason to believe otherwise. AbeListed's reckless and malicious behavior, through the worldwide reach of the Internet, has now jeapardized Woods' good name and reputation on an international scale. The documents sought pursuant to this Subpoena are relevant and material to the trial of this case because Woods needs the documents in order to identify and prosecute his defamation and invasion of privacy claims against AbeListed.

II. The records to be produced pursuant to the Subpoena and this Attachment 3 are with reference to the following Twitter account and user profile ID:

1. twitter.com/abelisted

2. @abelisted

3. mobile.twitter.com/abelisted

Collectively referred to herein as the "AbeListed Twitter Acct."

III. The records to be produced pursuant to Subpoena and this Attachment "3" are as follows:

1. Account user information for the AbeListed Twitter Acct, including any documents or writings (the term "writings" in this request, and each subsequent request using the term, means as defined by California Evidence Code Section 250) evidencing the name, address, telephone number, e-mail address(es), IP address(es) and/or any other available contact and/or identifying information for the holder(s) of the AbeListed Twitter Acct, and/or associated with the AbeListed Twitter Acct, both concurrently and at any time prior to the date of this request.

2. Any user records, data and writings (or a copy of the information contained therein) which evidence and identify each IP address (including date and time of use of said IP address) associated with and/or used at any time by any person in relation to creating or modifying or posting to the AbeListed Twitter Acct.

3. Any user records, data and writings (or a copy of the information contained therein) which evidence and identify the IP address (including date and time of use of said IP address) used by the user who posted the Tweet/Comment "@RealJamesWoods @banshapiro cocaine addict James Woods still sniffing and spouting," dated July 15, 2015 7:40 AM, at URL http://twitter.com/abelisted/status/621328418861248512

4. A list of all handle (i.e., @names) and associated user names, in addition to the AbeListed handle, used or otherwise associated at any time with the AbeListed Twitter Acct and/or its user(s).

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 37658

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Attorney Ordered to Identify Dead Client Who Taunted Jam

How James Woods Became Obama’s Biggest Twitter Troll. Actor James Woods has had a long career in Hollywood. But now he’s becoming almost as well known as the president’s biggest heckler on Twitter—and conservatives love him for it.

by Asawin Suebsaeng

December 31, 2014

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

That was James Woods in 2013. The 67-year-old actor had worked in Hollywood for decades, starring in such acclaimed films as Once Upon a Time in America and Oliver Stone’s Salvador, playing Rudy Giuliani, voicing a shady government agent in the Grand Theft Auto video game series, and even guest-starring on The Simpsons as a Kwik-E-Mart proprietor. But now his politics were offending the progressive sensibilities of the American film industry.

“Scratch a liberal, find a fascist every time,” Woods tweeted in April. These days the Oscar-nominated actor uses his Twitter account to broadcast his right-wing views to his 190,000 followers—and he’s arguably become President Obama’s biggest, most famous troll on Twitter.

“He’s the nicest guy you’ll ever meet, but his politics are, apparently, batshit crazy,” says Ben Dreyfuss, engagement editor at Mother Jones whose family—including movie star Richard—is friends with Woods.

The actor does have a tendency to latch on to popular conservative memes and conspiracy theories, among them the IRS, Benghazi, and Obamacare. And at least for the time being, he’s sticking to social media as his platform for bashing liberals.

“He is not doing any interviews on this subject,” Woods’s publicist told The Daily Beast. “He prefers to express himself through Twitter and leave it at that.”

Woods’s comments can sometimes be inflammatory. He used the slur “towel-heads” after the 9/11 attacks. He has said he believes Al Sharpton is a “race pimp” and a pig. He has called Obama a “true abomination.” And that was well before this Christmas, when he appeared to joke about Obama being a Muslim.

Woods’s diehard conservatism has led some to draw parallels between his Twitter persona and his character in the 2013 movie White House Down, an extremist hawk who spends most of his time on screen hating on a liberal black president.

Woods is significantly more aggressive and prolific in his ranting than Hollywood conservatives like Jerry Bruckheimer, Bruce Willis (who isn’t much of a Republican team player, anyway), and Sylvester Stallone (who also happens to be the most anti-gun celebrity in Hollywood). Woods’s tweets alone have made him a darling in certain conservative media circles.

“James Woods has a reputation in the business of not mincing words,” Breitbart posted in September 2013. “Woods has been a prolific, highly articulate, and politically incorrect conservative voice,” The Daily Caller raved the next month. A “fierce fighter for the truth regarding the tragedy in Benghazi,” proclaimed Twitchy, the Twitter curation site founded by Michelle Malkin that regularly highlights Woods’s tweets, in May.

“James Woods refuses to toe the Hollyweird line,” Twitchy managing editor Lori Ziganto told The Daily Beast in an email. “Woods uses Twitter to speak actual truth to power; conservatives rightly can’t get enough of this rare Hollywood bravery. Woods understands the power of Twitter.”

As for those who find his views extreme, they might very well read one of his quotes from a 2003 interview with Salon and imagine the actor commenting on his future self:

“I’ve never talked to an extreme liberal or conservative who could be disabused of his or her notions about their positions,” he said. “They are intractable in their thinking, they are unreasoning and unreasonable, and it’s just a waste of breath to talk to them.”

Ten years later, Woods would tweet: “I vowed if I were ever on Twitter, I would NEVER talk politics. That worked out pretty good…”

It’s probably too late to turn back now.

by Asawin Suebsaeng

December 31, 2014

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

“I don’t expect to work [in Hollywood] again.”

That was James Woods in 2013. The 67-year-old actor had worked in Hollywood for decades, starring in such acclaimed films as Once Upon a Time in America and Oliver Stone’s Salvador, playing Rudy Giuliani, voicing a shady government agent in the Grand Theft Auto video game series, and even guest-starring on The Simpsons as a Kwik-E-Mart proprietor. But now his politics were offending the progressive sensibilities of the American film industry.

“Scratch a liberal, find a fascist every time,” Woods tweeted in April. These days the Oscar-nominated actor uses his Twitter account to broadcast his right-wing views to his 190,000 followers—and he’s arguably become President Obama’s biggest, most famous troll on Twitter.

“He’s the nicest guy you’ll ever meet, but his politics are, apparently, batshit crazy,” says Ben Dreyfuss, engagement editor at Mother Jones whose family—including movie star Richard—is friends with Woods.

The actor does have a tendency to latch on to popular conservative memes and conspiracy theories, among them the IRS, Benghazi, and Obamacare. And at least for the time being, he’s sticking to social media as his platform for bashing liberals.

“He is not doing any interviews on this subject,” Woods’s publicist told The Daily Beast. “He prefers to express himself through Twitter and leave it at that.”

Woods’s comments can sometimes be inflammatory. He used the slur “towel-heads” after the 9/11 attacks. He has said he believes Al Sharpton is a “race pimp” and a pig. He has called Obama a “true abomination.” And that was well before this Christmas, when he appeared to joke about Obama being a Muslim.

Woods’s diehard conservatism has led some to draw parallels between his Twitter persona and his character in the 2013 movie White House Down, an extremist hawk who spends most of his time on screen hating on a liberal black president.

Woods is significantly more aggressive and prolific in his ranting than Hollywood conservatives like Jerry Bruckheimer, Bruce Willis (who isn’t much of a Republican team player, anyway), and Sylvester Stallone (who also happens to be the most anti-gun celebrity in Hollywood). Woods’s tweets alone have made him a darling in certain conservative media circles.

“James Woods has a reputation in the business of not mincing words,” Breitbart posted in September 2013. “Woods has been a prolific, highly articulate, and politically incorrect conservative voice,” The Daily Caller raved the next month. A “fierce fighter for the truth regarding the tragedy in Benghazi,” proclaimed Twitchy, the Twitter curation site founded by Michelle Malkin that regularly highlights Woods’s tweets, in May.

“James Woods refuses to toe the Hollyweird line,” Twitchy managing editor Lori Ziganto told The Daily Beast in an email. “Woods uses Twitter to speak actual truth to power; conservatives rightly can’t get enough of this rare Hollywood bravery. Woods understands the power of Twitter.”

As for those who find his views extreme, they might very well read one of his quotes from a 2003 interview with Salon and imagine the actor commenting on his future self:

“I’ve never talked to an extreme liberal or conservative who could be disabused of his or her notions about their positions,” he said. “They are intractable in their thinking, they are unreasoning and unreasonable, and it’s just a waste of breath to talk to them.”

Ten years later, Woods would tweet: “I vowed if I were ever on Twitter, I would NEVER talk politics. That worked out pretty good…”

It’s probably too late to turn back now.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 37658

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Attorney Ordered to Identify Dead Client Who Taunted Jam

Popehat v. James Woods SLAPP-down Match; Coming Soon To A Court Near You

from the can-i-get-front-row-seats? dept

by Mike Masnick

Techdirt

August 28, 2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

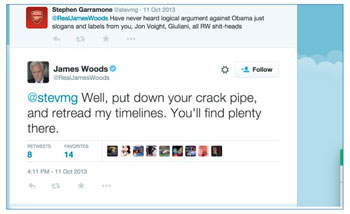

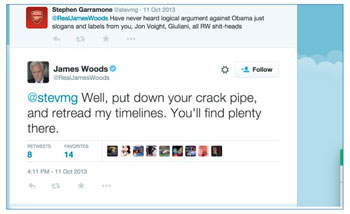

A month ago, we wrote about actor James Woods bizarrely suing a trollish Twitter user who had been mocking Woods on the site. The whole lawsuit seemed ridiculous. The specific tweet that sent Woods over the edge was this anonymous user (who went by the name "Abe List") saying "cocaine addict James Woods still sniffing and spouting." Soon after our post on the subject, Ken "Popehat" White posted an even better takedown entitled James Woods Punches the Muppet. That post has now been updated with a brief note that White has now been retained to defend the anonymous Twitter user. And, if that gets you excited for what to expect in the legal filings, well, you don't have wait. As first reported by Eriq Gardner at the Hollywood Reporter, White has filed the John Doe's opposition to Woods' attempt to unmask the guy. And it's worth reading.

Problem number one with Woods' suit is laid out right at the beginning of the filing, which is that Woods himself has a habit of accusing others of using illegal drugs as well, just as Abe List did:

The filing shows other tweets from Woods that have similar words that Woods complained about Abe List using, such as "clown" and "scum." As the filing notes, it appears Woods thinks that he can use those insults towards others, but if anyone uses them towards him, it's somehow defamatory.

The filing, quite reasonably, notes that these kinds of hyperbolic claims cannot be seen as defamatory, and since there's no legitimate claim here, there is no reason to do expedited discovery or to unmask Abe List, who is entitled to have his identity protected under the First Amendment.

Oh, and, not surprisingly, White will be filing an anti-SLAPP motion shortly, which may mean that Woods is going to have to pay for this mess that he caused.

The filing also notes that while Woods sent a subpoena to Twitter to try to seek Abe List's identity, the company turned it down as deficient. The full two page letter is in the filing below as Exhibit B, but a quick snippet on the First Amendment concerns:

Meanwhile, Woods has already filed a response in which he is still seeking to uncover the name of Abe List, and which repeats more ridiculous claims about the whole thing, starting off with the simply false claim that the original "cocaine addict" tweet was likely seen by "hundreds of thousands" of Woods' followers. That's wrong. They would only see if they followed both Woods and the Abe List account, which very few did.

The filing, somewhat hilariously, claims that calling someone "a joke," "ridiculous," "scum" and "clown-boy" are not protected by the First Amendment. Which makes me wonder what law school Woods' lawyers went to. Because that's just wrong:

Um... but Woods himself did exactly that (see above). It's standard hyperbolic speech, which is clearly not defamatory especially when mocking a public figure like Woods who has a history of using the same sort of hyperbolic insults on Twitter. Even more ridiculously, Woods' lawyers claim that by saying that the statement was a joke, that's Abe List admitting that he knew it was a false statement. I can't see that argument flying. I can see it backfiring big time once the anti-SLAPP motion is made.

So, what about those similar tweets made by Woods himself? His lawyers tell the court to ignore those piddly things.

Except, uh, again, Woods suggested someone smoked crack, just like Abe List joked that Woods was a cocaine addict. And, again, Woods and his lawyers are just wrong that all of Woods' followers would have seen Abe Lists' tweets. They're just factually wrong.

You never know how courts will rule in any particular case, no matter how ridiculous, but I have a hard time seeing how Woods gets out of this without having to pay two sets of lawyers -- his own and Ken White -- for filing a clearly bogus defamation case designed to shut up (and identify) an anonymous Twitter critic. No matter what, James Woods may not be a cocaine addict, but he has made it clear that he can dish it out but can't take it back when people make fun of him. What a clown.

from the can-i-get-front-row-seats? dept

by Mike Masnick

Techdirt

August 28, 2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A month ago, we wrote about actor James Woods bizarrely suing a trollish Twitter user who had been mocking Woods on the site. The whole lawsuit seemed ridiculous. The specific tweet that sent Woods over the edge was this anonymous user (who went by the name "Abe List") saying "cocaine addict James Woods still sniffing and spouting." Soon after our post on the subject, Ken "Popehat" White posted an even better takedown entitled James Woods Punches the Muppet. That post has now been updated with a brief note that White has now been retained to defend the anonymous Twitter user. And, if that gets you excited for what to expect in the legal filings, well, you don't have wait. As first reported by Eriq Gardner at the Hollywood Reporter, White has filed the John Doe's opposition to Woods' attempt to unmask the guy. And it's worth reading.

Problem number one with Woods' suit is laid out right at the beginning of the filing, which is that Woods himself has a habit of accusing others of using illegal drugs as well, just as Abe List did:

The filing shows other tweets from Woods that have similar words that Woods complained about Abe List using, such as "clown" and "scum." As the filing notes, it appears Woods thinks that he can use those insults towards others, but if anyone uses them towards him, it's somehow defamatory.

Plaintiff, an internationally known actor, is active on Twitter, a social media platform. There he is known for engaging in rough-and-tumble political debate. Plaintiff routinely employs insults like “clown” and “scum,” and even accuses others of drug use as a rhetorical trope....

But Plaintiff apparently believes that while he can say that sort of thing to others, others cannot say it to him. He has sued Mr. Doe for a derisive tweet referring to him as “cocaine addict James Woods still sniffing and spouting” in the course of political back-and forth.... He also complains, at length, that Mr. Doe has called him things like a “clown” and “scum.” Naturally, Plaintiff has himself called others “clown” or “scum” on Twitter.

The filing, quite reasonably, notes that these kinds of hyperbolic claims cannot be seen as defamatory, and since there's no legitimate claim here, there is no reason to do expedited discovery or to unmask Abe List, who is entitled to have his identity protected under the First Amendment.

Oh, and, not surprisingly, White will be filing an anti-SLAPP motion shortly, which may mean that Woods is going to have to pay for this mess that he caused.

The filing also notes that while Woods sent a subpoena to Twitter to try to seek Abe List's identity, the company turned it down as deficient. The full two page letter is in the filing below as Exhibit B, but a quick snippet on the First Amendment concerns:

First, Twitter objects because you have provided no documentation showing that the Court considered and imposed the First Amendment safeguards required before a litigant may be permitted to unmask the identity of an anonymous speaker. As courts have recognized, a trial court must strike a balance "between the well-established First Amendment right to speak anonymously, and the right of the plaintiff to protects its proprietary interests and reputation through the assertion of recognizable claims based on the actionable conduct of the anonymous, fictitiously-named defendants." Dendrite Int'l, Inc. v. Doe No. 3,775 A.2d 756, 760 (N.J. Super. A.D. 2001). Accordingly, before a service provider such as Twitter may be compelled to unmask an anonymous speaker, (1) a reasonable attempt to notify the user of the request and the lawsuit must be made, and (2) the plaintiff must make a prima facie showing of the elements of defamation. See Krinsky v. Doe, 72 Cal. Rptr. 3d 231, 239, 244-46 (Cal. Ct. App. 2008). Moreover, under California law, the party seeking discovery must demonstrate "a compelling need for discovery" that "outweigh[s] the privacy right when these two competing interests are carefully balanced." Digital Music News LLC v. Superior court of Los Angeles, 226 Cal. App. 4th 216, 229 (2014) (citing Lantz v. Superior court, 28 Cal. App. 4th 1839, 1853-54 (1994).

It does not appear that you will be able to meet these standards. The speech at issue appears to be opinion and hyperbole rather than a statement of fact. Further, the target of the speech is a public figure who purposefully injects himself into public controversies, and there has been no showing of actual malice. Attempts to unmask anonymous online speakers in the absence of a prima facie defamation claim are improper and would chill the First Amendment rights of speakers who use Twitter's platform to express their thoughts and ideas instantly and publicly, without barriers.

Meanwhile, Woods has already filed a response in which he is still seeking to uncover the name of Abe List, and which repeats more ridiculous claims about the whole thing, starting off with the simply false claim that the original "cocaine addict" tweet was likely seen by "hundreds of thousands" of Woods' followers. That's wrong. They would only see if they followed both Woods and the Abe List account, which very few did.

The filing, somewhat hilariously, claims that calling someone "a joke," "ridiculous," "scum" and "clown-boy" are not protected by the First Amendment. Which makes me wonder what law school Woods' lawyers went to. Because that's just wrong:

AL's outrageous claim appears to be the culmination of a malicious on-line campaign by AL to discredit and damage Woods' reputation, a campaign which began as early as December 2014. In the past, AL has referred to Woods with such derogatory terms as a "joke," "ridiculous," "scum" and "clown-boy." ... Although AL's rantings against Woods began with childish name calling, it has escalated beyond the protections of free speech, i.e., the First Amendment does not permit anyone to falsely represent to the public that another person is addicted to an illegal narcotic.

Um... but Woods himself did exactly that (see above). It's standard hyperbolic speech, which is clearly not defamatory especially when mocking a public figure like Woods who has a history of using the same sort of hyperbolic insults on Twitter. Even more ridiculously, Woods' lawyers claim that by saying that the statement was a joke, that's Abe List admitting that he knew it was a false statement. I can't see that argument flying. I can see it backfiring big time once the anti-SLAPP motion is made.

So, what about those similar tweets made by Woods himself? His lawyers tell the court to ignore those piddly things.

... to the extent AL or TG attempt to argue that the Court should consider other statements on their Twitter accounts, or any previous tweets by Mr. Woods, the argument is a red herring. First, there is no reason any of Mr. Woods' followers, all of whom were exposed to the defamatory statements, would even bother to investigate the speakers and/or their Twitter sites to determine if they were reliable sources. As to Mr. Woods, we are not aware of any false statements of fact made by Mr. Woods and his sometimes sharp commentary on political matters is irrelevant to the allegations here.

Except, uh, again, Woods suggested someone smoked crack, just like Abe List joked that Woods was a cocaine addict. And, again, Woods and his lawyers are just wrong that all of Woods' followers would have seen Abe Lists' tweets. They're just factually wrong.

You never know how courts will rule in any particular case, no matter how ridiculous, but I have a hard time seeing how Woods gets out of this without having to pay two sets of lawyers -- his own and Ken White -- for filing a clearly bogus defamation case designed to shut up (and identify) an anonymous Twitter critic. No matter what, James Woods may not be a cocaine addict, but he has made it clear that he can dish it out but can't take it back when people make fun of him. What a clown.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 37658

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Attorney Ordered to Identify Dead Client Who Taunted Jam

Part 1 of 2

James Woods vs. John Doe: Notice of Motion and Motion for an Order Compelling Non-Party Kenneth P. White to Answer Deposition Questions and Produce Documents; and An Order for Sanctions Against Non-Party Kenneth P. White in the amount of $9,040.55

by James Woods

MICHAEL E. WEINSTEN (BAR NO. 155680)

LINDSAY MOLNAR, ESQ (BAR NO. 272156)

LAVELY & SINGER

PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION

2049 Century Park East, Suite 2400

Los Angeles, California 90067-2906

Telephone: (310) 556-3501

Facsimile: (310) 556-3615

Email: [email protected]

[email protected]

Attorneys for Plaintiff JAMES WOODS

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES

JAMES WOODS, an individual,

Plaintiff,

vs.

JOHN DOE a/k/a "Abe List" and DOES 2 through 10, inclusive,

Defendants.

Case No.: BC 589746

[Hon. Mel Recana, Dept. 45]

NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR: (1) AN ORDER COMPELLING NON-PARTY KENNETH P. WHITE TO ANSWER DEPOSITION QUESTIONS AND PRODUCE DOCUMENTS; AND (2) AN ORDER FOR SANCTIONS AGAINST NON-PARTY KENNETH P. WHITE IN THE AMOUNT OF $9,040.55

[Declaration of Michael E. Weinsten and Separate Statement filed concurrently herewith]

Date: December 22, 2016

Time: 8:35 a.m.

Dept: 45

Reservation ID: 161109172908

Complaint Filed: July 29, 2015

Trial Date: None

TO ALL PARTIES AND THEIR ATTORNEYS OF RECORD HEREIN:

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on December 22, 2016, at 8:35 a.m., or as soon thereafter as the matter may be heard in Department 45 of the Los Angeles Superior Court, located at 111 North Hill Street, Los Angeles, California 90012, Plaintiff James Woods ("Plaintiff") will, and hereby does, move the Court for an order compelling Non-Party Kenneth P. White ("White") to (1) provide substantive responses without objection to the questions asked during his deposition and (2) produce documents responsive to Plaintiff s deposition subpoena.

Plaintiff brings this motion to compel White's deposition testimony pursuant to California Code of Civil Procedure § 2025.480(a). Plaintiff brings this motion after White refused, during his November 14, 2016 deposition, to answer any questions related to the actual identity of his client in this action - Defendant John Doe a/k/a "Abe List" - by improperly asserting the attorney-client privilege and other unfounded objections.

Plaintiff will also move the Court for an order compelling White to produce documents that he was required to produce pursuant to Plaintiff s deposition subpoena.

Plaintiff will also move the Court for an order that White pay to Plaintiff the sum of no less than $9,040.55 as the reasonable costs and attorney fees incurred by Plaintiff in connection with bringing the instant Motion and taking White's November 14, 2016 deposition.

This Motion is made and based upon this Notice, the accompanying Memorandum of Points and Authorities, the Separate Statement, the Declaration of Michael E. Weinsten and any exhibits attached thereto, the court's file herein, and any oral argument and other documentary evidence as may be Presented at the hearing.

Dated: November 30, 2016

LAVELY & SINGER

PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION

MICHAEL E. WEINSTEN

LINDSAY MOLNAR

By: MICHAEL E. WEINSTEN

Attorneys for Plaintiff JAMES WOODS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

• I. INTRODUCTION

• II. STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FACTS

o A. AL's Unsuccessful Anti-SLAPP Motion

o B. White's Unsubstantiated Claim That AL Died During The Appeal of the Court's Anti-SLAPP Ruling

o C. White's Unfounded and Bad-Faith Refusal to Answer Basic Deposition Questions and Produce Documents Concerning the Identity of His Purportedly Deceased Client

• III. LEGAL ARGUMENT

o A. A Motion To Compel Is Proper Where A Deponent Refuses To Answer Questions During The Examination Or Produce Documents At Deposition

o B. The Court Should Compel White To Answer Deposition Questions Relating to the Identity of AL Since This Information is Neither Private Nor Privileged And Is Critical To Woods' Ability To Effectively Prosecute His Claims Against AL

o i. Because AL's Privacy Rights Died With Him, White CannotWithhold AL' s Identity On Privacy Grounds

o ii. AL's Identity and Information Related To His Identity Is Not Protected By The Attorney-Client Privilege

o iii. Information Related to the Identity of AL Is Highly Relevant And Critical For Woods' To Prosecute His Claims Against AL

o C. White's Claim That Woods Is Not Entitled to Information Related to the Identity of AL Due to Fear of "Harassment" or "Intimidation" Is Unfounded

• IV. WHITE'S FAILURE TO PROVIDE ANY JUSTIFICATION FOR HIS FAILURE TO ANSWER DEPOSITION QUESTIONS AND OR PRODUCE DOCUMENTS RESPONSIVE TO THE SUBPOENA WARRANTS AN AWARD OF MONETARY SANCTIONS AGAINST HIM

• V. CONCLUSION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

• 4 AF Holdings LLC v. Doe, No. 2: 12-CV-1066 GEB GGH, 2012 WL 6042635 (E.D. Cal. 2012)

• Baird v. Koerner, 279 F.2d 623 (9th Cir. 1960)

• Beverly Hills Nat. Bank & Trust Co. v. Superior Court In and For Los Angeles County, 195 Cal. App. 2d 861 (1961)

• Brunner v. Superior Court 0/ Orange Cty., 9 51 Cal.2d 616 (1959)

• Doe v. Kamehameha Schools etc., 596 F.3d 1036 (9th Cir. 2010)

• Flynn v. Higham, 149 Cal.App.3d 677 (1983)

• Hays v. Wood, 25 Cal.3d 772 (1979)

• Hendrickson v. California Newspapers, Inc., 48 Cal.App.3d 59 (1975)

• Kramer v. Superior Court of Los Angeles County, 17 237 Cal. App. 2d 753 (1965)

• Krinsky v. Doe 6, 159 Cal.App. 4th 1154 (2008)

• Lugosi v. Universal Pictures, 20 25 Cal.3d 813 (1979)

• Moran v. Superior Court in and/or Sacramento County, 38 Cal. App. 2d 328 (1940)

• Pers. v. Farmers Ins. Grp. of Companies, 52 Cal. App. 4th 813

• Rosso, Johnson, Rosso & Ebersold v. Superior Court, 25 191 Cal.App.3d 1514 (1987)

• 26 Tien v. Superior Court, 139 Cal.App.4th 528 (2006)

• United States v. Doe, 28 655 F.2d 920 (9th Cir. 1980)

Statutes

• Code of Civil Procedure § 1987.2(a)

• Code of Civil Procedure § 2023.030(a)

• Code of Civil Procedure § 2025.010

• Code of Civil Procedure § 2025.480(j)

• Evidence Code § 952

• Evidence Code § 954

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

I. INTRODUCTION

This case arises from the publication of a malicious and fabricated accusation leveled against actor James Woods ("Woods") by an individual who hid behind the Twitter name "Abe List" (hereafter "AL"). In July 2015, AL falsely accused Woods of being a "cocaine addict" on the widely popular social media site Twitter and, after Twitter refused to remove the libelous statement, Woods was forced to file suit for defamation and invasion of privacy by false light to protect his good name and reputation.

Rather than face Woods' claims on the merits, AL's modus operandi from the very beginning of this lawsuit has been to utilize various procedural roadblocks to conceal his identity from Woods and delay the prosecution of Woods' claims. For example, shortly after Woods filed the Complaint, AL filed a frivolous (and ultimately nnsuccessful) anti-SLAPP motion, which was clearly intended solely to prevent his identity from being disclosed. When Woods then sought to conduct discovery in connection his opposition of the anti-SLAPP motion, AL vehemently opposed the motion, claiming that Woods first had to prove his entire prima facie case against AL before discovering AL's identity.

After this Court denied AL's anti-SLAPP and rightly held that Woods had "met his burden of showing a probability of prevailing" on his claims, AL filed afrivolous appeal of this COUli's order, once again trying to block the disclosure of his identity and further delaying the prosecution of Woods' claims. Then, when it was finally time for AL to file his reply brief - after Woods had already incurred the time and expense of filing a 50-page Respondents' brief - AL's counsel, Kenneth P. White ("White"), filed a declaration with the appellate court (1) stating that his client had passed away, (2) indicating that AL's estate would be substituting into the matter, and (3) requesting an extension of time for the filing of AL's reply brief However, no substitution was ever made. Instead, weeks later, White suddenly filed a dismissal of the appeal - which resulted in this case being remanded back to the trial court.

Critically, although White claims that AL is deceased, he has refused to provide any evidence whatsoever substantiating this claim. Moreover, when Woods' counsel reasonably requested that White at least provide the identity of his now-purportedly-deceased client - a fact which would be necessary in order to confirm whether AL is actually deceased - White refused.

As a result of White's staunch refusal to provide evidence of AL's purported client's death, or even AL's name, Woods was forced to take White's deposition on November 14,2016. During this deposition, White still refused to disclose AL' s identity (or produce the relevant documents requested in the deposition subpoena), asserting the unfounded objections that such information is private, subject to the attorney-client privilege, not relevant to the claims in this lawsuit, and harassing. [1]

Obviously, White's objections are meritless and in bad faith. First and foremost, AL's right to privacy died along with him and, in any event, White cannot assert this right on his deceased client's behalf. See Lugosi v. Universal Pictures, 25 Cal.3d 813,820,833 (1979) (dissenting Justices agreeing with majority that: "It is not disputed that the right of privacy is a personal one, which is not assignable and ceases with an individual's death.") (emphasis added). Second, AL's identity and information related to his identity are not subject to the attorney-client privilege - as these are merely facts, not communications. See Hays v. Wood, 25 Cal.3d 772,785 (1979) (rejecting attorney's claim that the identity of his clients are privileged). Indeed, Woods is unaware of even a single case where the attorney-client privilege was upheld to preclude an anonymous litigant from disclosing his name. Third, there is no question that AL's identity is relevant to Woods' ability to effectively prosecute his claims, conduct discovery and obtain a judgment against a known person - even more so in light of the fact that the Court has already found Woods has a "probability of prevailing" on his claims, Indeed, if White is unwilling to substantiate his claim that AL is deceased, Woods is entitled to investigate whether this claim is true. [2] Lastly, information related to AL's identity is clearly not being requested for purposes of "harassment" or "intimidation," nor has White has offered any factual or legal support for such an absurd objection (nor does any such support exist).

In light of the above, Woods' motion should be granted and White should be compelled to answer the deposition questions set forth in the concurrently-filed Separate Statement, as well as produce documents responsive to the Subpoena.

II. STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FACTS

A. AL's Unsuccessful Anti-SLAPP Motion

On July 29, 2015, Woods filed the instant lawsuit against AL for defamation and invasion of privacy by false light.

On September 2, 2015, AL filed an anti-SLAPP motion claiming that the defamatory tweet at issue was protected by the First Amendment and that Woods could not prevail on his claims because the tweet was not a statement of fact, but, instead, mere "rhetorical hyperbole" and "insult."

On February 8, 2016, the Court denied AL's anti-SLAPP motion, finding that Woods had "met his burden of showing a probability of prevailing" on his claims for defamation and invasion of privacy.

On February 11,2016, AL filed a Notice of Appeal of the Court's February 8, 2016 order denying his anti-SLAPP.

B. White's Unsubstantiated Claim That AL Died During The Appeal of the Court's Anti-SLAPP Ruling.

On August 26, 2016, while AL's appeal was pending, Woods' counsel received an email from White stating that there had been a "development in the Woods v. Doe matter," and requesting a time to speak. Declaration of Michael E. Weinsten ("Weinsten Decl."), ~2, Ex. A. During a telephone that same day, White informed Woods' counsel that AL had purportedly died. Weinsten Decl., ~2. White, however, would not respond to any of Woods' counsel's questions regarding the identity of AL, or how or when AL allegedly died. Id White also refused to provide any actual documentary evidence that AL is deceased. Id. Shortly thereafter, on October 21,2016, AL (or AL's estate), dismissed the pending appeal.

C. White's Unfounded and Bad-Faith Refusal to Answer Basic Deposition Questions and Produce Documents Concerning the Identity of His Purportedly Deceased Client

On November 3, 2016, Woods issued and served a Deposition Subpoena for Personal Appearance and Production of Documents and Things (the "Subpoena") on White. Weinsten Decl., Para. 3, Ex. B.

In addition to testimony, the Subpoena sought the production of the following categories of documents:

• DOCUMENTS sufficient to IDENTIFY John Doe a/k/a "Abe List", your client and the defendant in the lawsuit captioned James Woods v. John Doe a/k/a "Abe List", which is pending in Los Angeles Superior Court, Case No. BC589746.

• DOCUMENTS sufficient to IDENTIFY the personal representative of the estate of John Doe a/k/a "Abe List."

Weinsten Decl., Para. 3, Ex. B.