Excerpt from Memorandum Opinion Re Powell, Giuliani and My Pillow's Motions to DismissUSDC for the District of Columbia

US Dominion, Inc., et al., Plaintiffs, v. Sidney Powell, et al., Defendants,

Civil Action No. 1:21-cv-00040 (CJN)

8/11/21

IV. Analysis

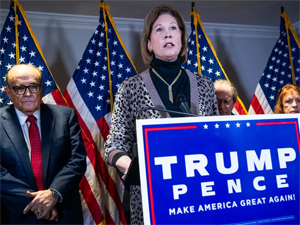

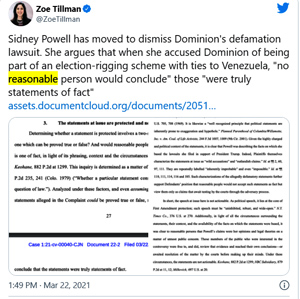

A. Statements of Fact or Opinion Powell alone argues that her statements cannot be defamatory because no reasonable person could conclude that they were statements of fact. According to Powell, her statements were either "opinions" that cannot be proven true or false or "legal theories . . . made in the context of pending and impending litigation." Powell’s Mot. at 43–44.

For a statement to be actionable as defamatory, it must at least express or imply a verifiably false fact about the plaintiff. Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 497 U.S. 1, 19–20 (1990). And while statements of opinion regarding matters of public concern cannot be defamatory if they do not contain or imply a provably false fact,

they are actionable if they imply a provably false fact or rely upon stated facts that are provably false. Id. at 20. "In deciding whether a reasonable factfinder could conclude that a statement expressed or implied a verifiably false fact about [the plaintiff], the court must consider the statement in context." Weyrich v. New Republic, Inc., 235 F.3d 617, 624 (D.C. Cir. 2001).6

Powell contends that no reasonable person could conclude that her statements were statements of fact because they "concern the 2020 presidential election, which was both bitter and controversial," Powell’s Mot. at 38, and were made "as an attorney-advocate for [Powell’s] preferred candidate and in support of her legal and political positions," id. at 39. As an initial matter,

there is no blanket immunity for statements that are "political" in nature: as the Court of Appeals has put it, the fact that statements were made in a "political ‘context’ does not indiscriminately immunize every statement contained therein." Weyrich, 235 F.3d at 626. It is true that courts recognize the value in some level of "imaginative expression" or "rhetorical hyperbole" in our public debate. Milkovich, 497 U.S. at 2.7 But

it is simply not the law that provably false statements cannot be actionable if made in the context of an election.8

Powell similarly argues that her statements were protected commentary about other lawsuits. But

Powell cannot shield herself from liability for her widely disseminated out-of-court statements by casting them as protected statements about in-court litigation; an attorney’s out-of-court statements to the public can be actionable, even if those statements concern contemplated or ongoing litigation. Messina v. Krakower, 439 F.3d 755, 761–62 (D.C. Cir. 2006) (recognizing no privilege when statement is "published to persons not having an interest [in] or connection to the litigation") (quoting Finkelstein, Thompson & Loughran v. Hemispherx Biopharma, Inc., 774 A.2d 332, 342 (D.C. 2001)); see also Williams v. Burns, 540 F. Supp. 1243, 1247 (D. Colo. 1982) (contemplating actionable defamation claim for attorney’s statements while representing client during business transaction).

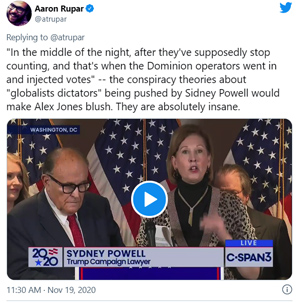

The question, then, is whether a reasonable juror could conclude that Powell’s statements expressed or implied a verifiably false fact about Dominion. Milkovich, 497 U.S. at 19–20. This is not a close call. To take one example, Powell has stated publicly that she has "evidence from [the] mouth of the guy who founded [Dominion] admit[ting that] he can change a million votes, no problem at all." Powell Compl. ¶ 181(j). She told audiences that she would "tweet out the video." Id. These statements are either true or not; either Powell has a video depicting the founder of Dominion saying he can "change a million votes," or she does not.

To take another example, Powell has stated that she could "hardly wait to put forth all the evidence . . . on Dominion, starting with the fact it was created to produce altered voting results in Venezuela for Hugo Chávez." Id. ¶ 181(e). Again, this statement is either true or it is not; either Dominion was created to produce altered voting results in Venezuela for Hugo Chávez or (as Dominion alleges) it was not.9

Take a few more examples. Powell has stated publicly that Dominion "flipped," "weighted," and "injected" votes during the 2020 election, see supra at p. 7; Powell Compl. ¶¶ 181(v), 181(ii), 181(u); either Dominion did so or (as Dominion alleges) it did not. Powell has claimed that state officials received kickbacks in exchange for using Dominion machines, id. ¶ 181(g); either state officials received such kickbacks or (as Dominion alleges) they did not. All of these statements, and many others alleged in Dominion’s Complaint, "expressed or implied a verifiably false fact" about Dominion. See Weyrich, 235 F.3d at 624. Powell argues that these statements are merely her own interpretation of "underlying facts [that] have been disclosed." Powell’s Mot. at 32. Statements may not be actionable if the "defendant provides the facts underlying the challenged statements, [and] it is ‘clear that the challenged statements represent [her] own interpretation of those facts, . . . leav[ing] the reader free to draw his own conclusions.’" Bauman v. Butowsky, 377 F. Supp. 3d 1, 11 n.7 (D.D.C. 2019) (quoting Adelson v. Harris, 973 F. Supp. 2d 467, 490 (S.D.N.Y. 2013), aff’d, 876 F.3d 413 (2d Cir. 2017)). But with respect to many of Powell’s allegedly defamatory statements,

Dominion alleges (and for the purposes of the Motion to Dismiss, the Court must accept as true) that she lied about having (or at the very least has not disclosed) her purported "underlying facts." For example, Powell has stated that she has "evidence from [the] mouth of the guy who founded [Dominion] admit[ting that] he can change a million votes, no problem at all." Powell Compl. ¶ 181(j). She has not, however, disclosed that video. She has also claimed that Dominion paid "kickbacks and benefits" to the families of Georgia public officials. Id. ¶ 181(n). But the only evidence to which Powell points in support of this claim is an undated (and allegedly doctored) Georgia state certificate stating that Dominion’s systems had "been thoroughly examined and tested and found to be in compliance with" Georgia law. Id. ¶ 39. That certificate provides no evidence of illicit payments to public officials’ families; it is certainly not, as Powell has argued, evidence . . . from various whistleblowers that are aware of substantial sums of money being given to family members of state officials who bought this software. . . . $100 million packages for new voting machines suddenly, in multiple states, and benefits ranging from financial benefits for family members to sort of what I would call election insurance, because they know that they can win the election if they are using that software.

Id. ¶ 181(g). More generally,

Dominion alleges that for many of Powell’s statements, the evidence to which she points is either false or provides no factual basis for what she said—and at this stage in the litigation, the Court must assume the truth of these allegations. See Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 664 (2009).

In sum,

Dominion has adequately alleged that Powell made a number of statements that are actionable because a reasonable juror could conclude that they were either statements of fact or statements of opinion that implied or relied upon facts that are provably false. See Milkovich, 497 U.S. at 20.10

B. Actual Malice Powell and Lindell both argue that Dominion has failed to allege that they made their defamatory statements "with ‘actual malice,’ that is, with ‘knowledge that [they were] false or with reckless disregard of whether [they were] false or not.’" Liberty Lobby, Inc. v. Dow Jones & Co., 838 F.2d 1287, 1292 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (quoting N.Y. Times Co. v. Sullivan, 370 U.S. 254, 280 (1964)).11

A defendant acts in reckless disregard of the truth if she "in fact entertained serious doubts as to the truth of [its] publication" or acted "‘with a high degree of awareness of . . .probable falsity.’" St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727, 731 (1968) (quoting Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74 (1964)). The "‘serious doubt’ standard requires a showing of subjective doubts by the defendant." Tavoulareas v. Piro, 817 F.2d 762, 789 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (en banc); see also St. Amant, 390 U.S. at 731 (explaining that "reckless conduct is not measured by whether a reasonably prudent man would have published, or would have investigated before publishing" the statement); Jankovic v. Int’l Crisis Grp., 822 F.3d 576, 589 (D.C. Cir. 2016) ("[I]t is not enough to show that defendant should have known better; instead, the

plaintiff must offer evidence that the defendant in fact harbored subjective doubt."). Subjective doubt can be proven through "the cumulation of circumstantial evidence [and] direct evidence," id. at 589 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted),

demonstrating that the defendant was "subjectively aware that it was highly probable that [its] story was ‘(1) fabricated; (2) so inherently improbable that only a reckless person would have put [it] in circulation; or (3) based wholly on an unverified anonymous telephone call or some other source that [it] had obvious reasons to doubt.’" Lohrenz v. Donnelly, 350 F.3d 1272, 1283 (D.C. Cir. 2003) (quoting Tavoulareas, 817 F.2d at 790)).

a. Powell Dominion argues that it has cleared this high bar. As to Powell,

Dominion contends it has alleged not only that Powell’s claims are so inherently improbable that only a reckless person could have believed them, but also that she deliberately ignored the truth in favor of relying on facially unreliable sources, intentionally lied about and fabricated evidence to support a preconceived narrative about election fraud, and did so to raise her own public profile and make a profit. Powell’s primary argument is that she could not have "entertained serious doubts as to the truth" or acted with a "high degree of awareness" of the "probable falsity" of her claims because she relied on sworn declarations and other evidence that supported her statements. Powell’s Mot. at 46–48; see St. Amant, 390 U.S. at 731. But

there is no rule that a defendant cannot act in reckless disregard of the truth when relying on sworn affidavits—especially sworn affidavits that the defendant had a role in creating. And Dominion alleges that Powell’s "evidence" was either falsified by Powell herself, misrepresented and cherry-picked, or so obviously unreliable that Powell had to have known it was false or had acted with reckless disregard for the truth. See, e.g., Powell Compl. ¶¶ 91–92, 7.

Powell again faces an obvious hurdle in the fact that she has never produced (nor mentioned in any sworn affidavit) the video of Dominion’s founder that she claims to possess, see supra at p.6;

a reasonable juror could conclude that Powell has not produced the video because she doesn’t have it. Dominion also alleges that Powell doctored a certificate from the Georgia Secretary of State to make it appear as though Georgia officials purchased Dominion machines and software on a rushed timeline. Powell Compl. ¶ 91. (The certificate, which is publicly available on the Georgia Secretary of State’s website, includes the Georgia Secretary of State’s date, seal, and signature—but Powell claimed that the Dominion certification was "undated" and filed a copy of the certificate that was missing the date, seal, and signature during the course of her election litigation in Georgia. Id.)

Dominion also alleges that Powell had a hand in drafting the declarations she touts as evidence of her claims. For example, Dominion alleges that the "military intelligence expert" who was the source for one declaration has admitted that he never actually worked in military intelligence, that the declaration Powell’s law firm drafted for him was "misleading," and that he was "trying to backtrack" on it. Id. ¶ 5. Dominion further alleges that after that source’s recantation, Powell claimed that the declaration was actually from a different anonymous source (instead of investigating whether there was a reason to doubt the truth of the original source’s claims). Id. As for the other anonymous declarations proffered by Powell, Dominion alleges that they bear distinct signs of having been drafted by Powell herself. Indeed, certain sections in two of the declarations are almost completely identical. Id. ¶ 90.

More generally, Dominion alleges that the declarations provide no facts to support Powell’s claims that Dominion flipped, stole, weighted, or injected any votes into a U.S. election. For example, one declaration says that "vote counting was abruptly stopped in five states using Dominion software"; that at that time "Donald Trump was significantly ahead in the votes"; and that "[w]hen the vote reporting resumed the very next morning there was a very pronounced change in voting in favor of the opposing candidate, Joe Biden." Pearson v. Kemp, No. 1:20-cv-04809 (N.D. Ga. Nov. 25, 2020) [ECF No. 1-2 at ¶ 26].

The declaration provides no factual support for the proposition that Dominion had flipped votes from Trump to Biden, and it certainly says nothing about Dominion having been created in Venezuela. Powell Compl. ¶ 181(e). A second declaration provides even less support; while it mentions Smartmatic, it says nothing about Dominion or a U.S. election. See generally Pearson v. Kemp, No. 1:20-cv-04809 (N.D. Ga. Nov. 25, 2020) [ECF No. 1-3 at ¶ 11].

Dominion further alleges that Powell’s "expert" reports are inherently unreliable and, as a former federal prosecutor, Powell had good reason to doubt their veracity. Powell Compl. ¶ 104.

In particular, it alleges that one expert was involved in a recent fraud case where the judge "ordered [the ‘expert’] to pay more than $25,000 after finding that she violated consumer protection laws by misspending money she raised and soliciting donations while misrepresenting her experience and education," id. ¶ 105, and that another was found to have provided "materially false information" in support of his claims of vote manipulation after referencing locations in Minnesota when alleging voter fraud in Michigan, id. ¶ 106. (That expert has also publicly claimed that George Soros, President George H.W. Bush’s father, the Muslim Brotherhood, and "leftists" helped form the "Deep State" in Nazi Germany in the 1930s—which would have been a remarkable feat for Soros, who was born in 1930. Id.) Dominion also alleges that a third expert has been rejected by another federal court for his "sheer unreliability," id. ¶ 107, and a fourth has declared, under penalty of perjury, that there was a pattern of improbable vote reporting in a Michigan county that does not exist, id. ¶ 108. According to Dominion, an experienced litigator like Powell either knew (or should have known) about these grave problems with her experts’ reliability, and thus she must have "entertained serious doubts as to the truth" of her statements or at a minimum acted "with a high degree of awareness of [their] probable falsity." Id. ¶¶ 104–09; see St. Amant, 390 U.S. at 731.

Dominion also alleges that Powell cherry-picked and took out of context statements regarding general concerns about election security made by Professor Andrew W. Appel. Powell Compl. ¶ 89. According to Dominion, Professor Appel’s research regarding election security is reputable, but concerns "a decades-old machine not designed by Dominion [and] not used in the 2020 election in any of the swing states . . . challenged by Powell." Id. (emphasis added). Indeed, Dominion alleges that Professor Appel stated that he "ha[s] never claimed that technical vulnerabilities have actually been exploited to alter the outcome of any US [sic] election" and that "no credible evidence has been put forth that supports a conclusion that the 2020 outcome in any state has been altered through technical compromise." Id. (emphasis omitted). A reasonable juror could conclude that Powell’s reliance on Professor Appel’s research when he has stated that there is "no credible evidence" of fraud is evidence of at least reckless disregard. See Zimmerman v. Al Jazeera Am., LLC, 246 F. Supp. 3d 257, 283–84 (D.D.C. 2017).

Dominion argues that its allegations regarding falsified documents, inherently unreliable sources, misrepresentations about other evidence, and Powell’s shifting positions reflect actual malice. It also argues that Powell had reasons for this conduct: to raise funds, to raise her public profile, and to curry favor with President Trump. Powell Compl. ¶¶ 75, 80, 185. Powell argues that Dominion has no facts to support these claims. But Dominion alleges that Powell repeatedly solicited donations to her law firm and DTR while making her claims, id. ¶ 58;12 that President Trump pardoned her client, Michael Flynn, on the same day she filed her first lawsuit challenging the results of the 2020 election, id. ¶ 80; and that in November 2020, "someone purchased the web domain sidneypowellforpresident.com," id. ¶ 71.

While it is true that "evidence of ill will ‘is insufficient by itself to support a finding of actual malice,’" Tah, 991 F.3d at 243 (quoting Tavoulareas, 817 F.2d at 795 (en banc) (emphasis added)); see also Harte-Hanks Commc’ns, Inc. v. Connaughton, 491 U.S. 657, 665 (1989) ("[A defendant’s] motive . . . cannot provide a sufficient basis for finding actual malice."), Dominion has proffered much more. For the reasons discussed,

Dominion has adequately alleged that Powell made her claims knowing that they were false, or at least with serious doubts as to their truthfulness. b. Lindell As for Lindell, Dominion contends that his claims were so inherently improbable that only a reckless man would have made them, that he intentionally disregarded evidence of their falsity, that he relied on obviously unreliable sources, and that he made his claims in accordance with a preconceived narrative that he constructed for financial gain. Like Powell, Lindell argues that Dominion has failed to allege actual malice because he has "evidence" to support his claims (and because he has never expressed doubt as to their truthfulness). Lindell’s Mot. at 29–41. But the majority of the evidence to which Lindell points is outside of the Complaint, and the Court cannot rely on this information at this time. See Menoken v. Dhillon, 975 F.3d 1, 8 (D.C. Cir. 2020) ("In considering claims dismissed pursuant to Rule 12 (b)(6), we accept a plaintiff’s factual allegations as true and draw all reasonable inferences in a plaintiff’s favor. . . . [T]he district court erred by relying on two documents outside the complaint."); Zimmerman, 246 F. Supp. 3d at 285 (rejecting defendants’ attempt to rebut the complaint’s allegations of fact and denying defendants’ motion to dismiss defamation claim).

Dominion alleges that Lindell has stated, among other things, that Dominion committed the "biggest crime ever committed in election history against our country and the world" and stole the 2020 election by using an algorithm to flip and weight votes in its machines; that Trump received so many votes that that algorithm broke on election night; that Dominion’s voting machines were "built to cheat" and "steal elections"; that a fake spreadsheet with fake IP and MAC addresses was "a cyber footprint from inside the machines" proving that they were hacked; and that Dominion’s plot was kept under wraps because the government had not really investigated claims of election fraud (due to then-Attorney General Bill Barr becoming "corrupt" and having been "compromised"). Lindell Compl. ¶¶ 103, 114, 165(e), 165(p), 165(x), 170. As a preliminary matter,

a reasonable juror could conclude that the existence of a vast international conspiracy that is ignored by the government but proven by a spreadsheet on an internet blog is so inherently improbable that only a reckless man would believe it. See St. Amant, 390 U.S. at 732.

But Dominion also alleges other facts that make those claims even more obviously improbable (or at least indicate that a reasonable juror could conclude that those claims are inherently improbable), including (1) public statements by election security specialists, Attorney General Barr, numerous government agencies, and elected officials; (2) independent audits; and (3) paper ballot recounts that disproved those claims. Lindell Compl. ¶¶ 2, 3, 33–34, 40, 71, 72, 92, 167.

Dominion also alleges that Lindell was made aware of that countervailing evidence in Dominion’s retraction letters, id. ¶¶ 63, 69, but—instead of reconsidering his claims in light of the mountain of evidence against them—doubled down and "dare[d] Dominion to sue [him]," id. ¶ 160. To be sure, a demand letter that is ignored, without more, does not demonstrate actual malice. Chandler v. Berlin, No. 18-CV-02136 (APM), 2020 WL 5593905, at *4 (D.D.C. Sept. 18, 2020); Parisi v. Sinclair, 774 F. Supp. 2d 310, 320 (D.D.C. 2011). But here, the Complaint rests on much more than Lindell’s refusal to retract; it also alleges that

Lindell recklessly disregarded the truth by relying on obviously problematic sources to support a preconceived narrative he had crafted for his own profit. Moreover,

Dominion alleges that the evidence on which Lindell did rely contains glaring discrepancies rendering it wholly unreliable. Lindell, like Powell, relied on the "forensic expert" who had provided "materially false information" in support of his claims of vote manipulation and who had claimed that George Soros, President George H.W. Bush’s father, the Muslim Brotherhood, and "leftists" all had a role in forming the Nazi "Deep State" in the 1930s. Lindell Compl. ¶ 71. As for the spreadsheet Lindell tweeted as "evidence" that "President Trump got around 79m votes to 68m for Biden," id. ¶¶ 75–76, Dominion alleges that the spreadsheet is obviously fake. In particular, the Complaint alleges that, although the spreadsheet purports to list IP addresses for election hackers and their targets, id., the listed "[t]arget" IP addresses are actually the addresses for the website of a county in a swing state (not for a voting machine or device), id. ¶ 81. And according to Dominion, the MAC addresses in the spreadsheet (which should identify the specific devices involved in the purported hacks) are not even MAC addresses that exist. Id. ¶¶ 83–89.

As for Lindell’s purported profit motive, Dominion alleges that Lindell knew that appealing to Trump supporters would be "good for business," id. ¶ 22, and that his true motive is apparent in the repeated tying together of his election fraud claims and promotion of MyPillow products. Like Powell, Lindell correctly notes that allegations of a defendant’s ill will or profit motive, without more, do not satisfy the actual malice standard. See Harte-Hanks, 491 U.S. at 666–67. But again, Dominion has alleged more:

in addition to alleging that Lindell’s claims are inherently improbable, that his sources are unreliable, and that he has failed to acknowledge the validity of countervailing evidence, Dominion has alleged numerous instances in which Lindell told audiences to purchase MyPillow products after making his claims of election fraud and providing MyPillow promotional codes related to those theories. In totality, it has adequately alleged that Lindell made his claims knowing that they were false or with reckless disregard for the truth.13

C. Deceptive Trade Practices Claims With respect to Dominion’s deceptive trade practices claims, Powell and Lindell argue that Dominion fails to state a claim under the relevant statutes, though for different reasons.

Powell argues that she cannot be liable for deceptive trade practices under Georgia law because Dominion has not alleged that she was "engaged in trade and commerce of goods." Powell’s Mot. at 52. She points to a single case in which the court granted summary judgment to the defendant on a deceptive trade practices claim when the defendant was engaged "neither in the business of selling or distributing the substances at issue, nor in the business of selling or distributing products similar to those sold and distributed by Plaintiffs." Int’l Brominated Solvents Ass’n v. Am. Conf. of Governmental Indus. Hygienists, Inc., 625 F. Supp. 2d 1310, 1318 (M.D. Ga. 2008). But the court reached that conclusion only after distinguishing other cases in which the defendant had a "financial interest" in the promulgation of its statements, id.; when such an interest exists, there is no requirement that the defendant be engaged in the trade and commerce of goods at issue, see Davita Inc. v. Nephrology Assocs., P.C., 253 F. Supp. 2d 1370, 1380 (S.D. Ga. 2003) (permitting a deceptive trade practices claim to proceed when plaintiffs pleaded that defendant made false and misleading comments, statements disparaged plaintiffs’ services and business, and maliciousness was ascertainable from complaint). Dominion, in contrast, has pleaded that Powell had a financial interest in the promulgation of her statements. See supra at 23.

Lindell, in turn, argues that Dominion’s deceptive trade practices claim is merely an attempt to avoid the requirements of the First Amendment. But Dominion has satisfied those requirements, see supra at pp. 15 n.7, 24–26, and the Minnesota deceptive trade practices statute expressly contemplates that conduct might be actionable as both a common law tort and under the statute by providing relief "in addition to remedies otherwise available against the same conduct under the common law," Minn. Stat. § 325D.45(3). And Lindell’s argument that only injunctive relief is available under the Minnesota statute, Lindell’s Mot. at 38, ignores that Dominion does seek injunctive relief, Lindell Compl., Prayer for Relief.

_______________

Notes:6 Powell argues that Colorado law applies to Dominion’s defamation claim. Powell’s Mot. at 22. But because Colorado also uses the Milkovich standard to determine whether a statement is actionable, see NBC Subsidiary (KCNC-TV), Inc. v. Living Will Ctr., 879 P.2d 6, 9–13 (Colo. 1994), the Court need not reach the choice-of-law question.

7 Such "imaginative expression" or "rhetorical hyperbole" is permitted under the theory that "the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market." Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting); Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 460–61 (2011). But that free trade of ideas depends on a common understanding of the facts, which is undermined by provably untrue statements.

8 MyPillow appears to similarly argue that the First Amendment grants some kind of blanket protection to statements about "public debate in a public forum." MyPillow’s Mot. at 10. Again, there is no such immunity. See Weyrich, 235 F.3d at 626. Instead, the First Amendment safeguards our "profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open," Tah v. Global Witness Publ’g, Inc., 991 F.3d 231, 240 (D.C. Cir. 2021) (quoting N.Y. Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 270 (1964)) (internal quotation marks omitted), by limiting viable defamation claims to provably false statements made with actual malice.

9 The Venezuela theory presumably finds its roots in the Venezuelan origins of Smartmatic, a different company that Giuliani alleges owns Dominion, id. ¶ 101, but that Dominion alleges is its competitor with no connection—either through ownership or software—with Dominion, id. ¶ 183.

10 DTR argues that it did not make any statements about Dominion. Powell’s Mot. at 51. But Dominion alleges that Powell made her statements (at least in part) as an agent of her law firm and an agent of DTR, and so (at this point in the proceedings) Powell’s statements can be imputed to DTR. Dominion’s Mem. in Opp’n to Powell’s Mot. to Dismiss ("Powell Opp’n"), ECF No. 39 at 50–51. In particular, Dominion alleges that Powell acted as an agent of DTR when she solicited donations for it during her defamatory television appearances, Powell Compl. ¶¶ 26, 126, and for her law firm when publishing online the declarations it filed in its election lawsuits, id. ¶ 151. Aside from the agency theory, Dominion also alleges that DTR independently published Powell’s statements on its website. See, e.g., id. ¶¶ 52, 58.

11 For the purposes of the Motions, Dominion does not dispute that it must plead actual malice but argues that it has alleged ample facts to demonstrate that the Defendants acted with the requisite intent. Powell Opp’n at 23–37; Dominion’s Mem. in Opp’n to Lindell’s Mot. to Dismiss ("Lindell Opp’n"), ECF No. 47 at 13–34.

12 Dominion alleges that Powell leveraged DTR to collect donations under false pretense. In particular, Dominion alleges that Powell has described DTR as a "non-profit working to help [her] defend all [of her election lawsuits] and to defend [her as an individual]," Powell Compl.¶ 156 (emphasis omitted), and represented that it is a 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organization, id. ¶¶ 17–19, but that it appears as neither on the IRS website, id. ¶ 20. And it argues that Powell used DTR donations for personal gain, as indicated by the lack of separation between DTR, Powell, and her law firm: DTR’s and the law firm’s websites are connected through at least ten hyperlinks and encouraged users to donate money by checks payable to the law firm’s "Defending the Republic Election Integrity Fund," id. ¶¶ 175–76, or directly to DTR (but mailed to the law firm’s address), id. ¶ 177. According to Dominion, the DTR website began collecting donations before DTR even existed as a corporate entity. Id. ¶ 17.

13

MyPillow argues that Lindell’s statements cannot be imputed to it. MyPillow’s Mot. at 29. But a corporation may be liable for an executive’s conduct when the executive was acting within the scope of his employment and in furtherance of the company’s business, see Palin v. N.Y. Times Co., 940 F.3d 804, 815 (2d Cir. 2019) (determining that a complaint stated a claim for defamation against The New York Times where it alleged facts giving rise to a plausible inference that the paper’s agents recklessly disregarded the truth); Mangan v. Corp. Synergies Grp., Inc., 834 F. Supp. 2d 199, 202–04 (D.N.J. 2011) (deciding that a complaint stated a claim for defamation against a corporation where CEO made allegedly defamatory statements). Here, Dominion alleges that

Lindell repeatedly made his statements while being identified as the CEO of MyPillow, Lindell Compl. ¶¶ 51, 70, 96, and at MyPillow-sponsored rallies at which he furthered those claims, id. ¶¶ 35, 165, and that MyPillow accepted promotional codes distributed during Lindell’s appearances that alluded to those claims (e.g., "FightforTrump"), id. ¶ 67.