Expert Report of Kathleen Blee (Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Bailey Dean of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh) and Peter Simi (Associate Professor of Sociology, Chapman University)

Sines v. Kessler, No. 17-cv-00072:

Submitted on July 20, 2020

HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL UNDER PROTECTIVE ORDER

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

ASSIGNMENT

SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS

REPORT

A. Background . 3

1. Methodology of Our Analysis

2. The Concept of Culture Frames This Report

B. The White Supremacist Movement Exhibits a Set of Core Characteristics

1. The WSM is Characterized by a Racist Ideology Based on White Supremacism, Anti-Semitism

and Hostility Toward Immigrants, Social Minorities, and Feminism

2. The WSM is Characterized by a Radical Division Between Insiders and Outsiders

3. The WSM is Highly Decentralized, Yet Coordinated

4. The WSM is Characterized by a High Degree of Internal Conflict

5. The WSM Utilizes New Communication Technologies

6. The WSM Utilizes Double-Speak

7. The WSM Focuses on Optics and Utilizes Front-Stage and Back-Stage Behavior

8. The WSM is Characterized by the Use of Violence

a. The WSM Promotes Three Key Ideas That Trigger Racial Violence

i. The White Race is Threatened

ii. Jews, Nonwhites, “Commies,” and Other Enemies Threaten the White Race

iii. The Destruction of the White Race is Imminent

b. The WSM Glorifies Violence

c. The WSM Normalizes Violence

i. Constant and Pervasive Violent Messaging

ii. Repertoires of Violence

a) Coordinated Violence

b) WSM-Supported Violence by Individuals

iii. Ritualistic Displays of White Power

9. The WSM Socializes Its Recruits to Utilize Racially-Motivated Violence

10. The WSM Utilizes Strategies of Deniability

11. Summary of the WSM

C. Defendants’ Actions Evince an Involvement in, and Deep Familiarity with, the WSM

D. Defendants Participated in and Praised the Use of WSM Tactics at Pre-UTR Events

E. Defendants Exhibited the Characteristics of the WSM When Planning and Organizing UTR

1. Defendants Disseminated White Supremacist and Anti-Semitic Ideologies In Planning and Organizing UTR

2. Defendants Expressed A Radical Division Between Insiders and Outsider When Planning and Organizing UTR

3. Defendants Utilized New Communication Technologies to Plan UTR

4. Defendants Utilized Double-Speak When Planning and Organizing UTR

5. Defendants Engaged in Front-Stage and Back-Stage Behavior Typical of the WSM

6. Defendants’ Plans for UTR Mirrored WSM Tactics in Calling for Violence

a. The Defendants Promoted the Key Ideas That Trigger Racial Violence in the WSM

b. Defendants Glorified Violence While Planning and Organizing UTR

c. The Defendants Used Constant and Pervasive Messaging of Violence

d. Defendants Recruited UTR Participants That Were Willing to Utilize Violence

e. The Violence Planned on Discord Played Out on August 11-12, 2017, By Both Defendants and Other Discord Participants

f. The Defendants Ratified Their Use of WSM-Style Violence After the Rally

7. Defendants Utilized Strategies of Deniability Common to the WSM

8. Conclusion

ASSIGNMENT

Kathleen M. Blee is Distinguished Professor of sociology and Bettye J. and Ralph E. Bailey Dean of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences and the College of General Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. She specializes in social movements, including racist/anti-Semitic and rightwing movements, racial violence, and microsociology. Her curriculum vitae is attached as Appendix A. Peter Simi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at Chapman University. He has studied extremist groups and violence for more than 20 years, conducting interviews and observation with a range of violent gangs and political extremists. His curriculum vitae is attached as Appendix B. Professor Blee and Professor Simi each received $30,000 in compensation for their time rendering this report.

We have been retained as expert witnesses for Plaintiffs, to apply our expertise in the characteristics of the historical white supremacist movement to our examination of the materials in this case and analyze whether the Defendants utilized the tools and tactics of the white supremacist movement in planning and implementing the events on August 11-12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia. Our findings in this matter were reached after our review of the documents available, and from utilizing the knowledge and expertise we have obtained based on our years of experience studying and publishing on the white supremacist movement. We considered the following facts and data in coming to the opinions for this report: (i) the sources identified in footnotes to this report; (ii) the sources identified in Appendix C; (iii) communications on Discord produced in this litigation, reviewed using the search terms identified in Appendix C; and (iv) other material produced in this litigation.

SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS

Based on our decades of research and publishing on white supremacism in the United States and our analysis of the organization and events associated with Unite the Right (UTR) in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017, we conclude that:

● The white supremacist movement (WSM) in the United States has consistently utilized, supported, and glorified violence as a strategy to promote its message and secure white supremacy.

● Defendants were active in and knowledgeable about the culture and networks of the WSM prior to UTR.

● UTR was organized to promote the agenda of the WSM.

● To organize UTR, Defendants used the cultural symbols, rituals, slogans, language, and references to historical figures that are the hallmarks of the WSM.

● Defendants shaped and made use of WSM culture and networks to recruit participants and to plan and execute UTR.

● The coordinated race-based violence facilitated and committed by Defendants at UTR is emblematic of WSM tactics.

REPORT

A. Background

This report is based on our decades of research and publishing on white supremacism in the United States, our review of the relevant scholarship on this topic, and our analysis of information and evidence about the Defendants associated with the August 11-12, 2017, UTR events in Charlottesville, Virginia.

1. Methodology of Our Analysis

The methodological steps in our analysis follow the research protocols that are standard in rigorous qualitative analyses in the social sciences, as codified in a report by the National Science Foundation1 for which one of the authors of this report (Blee) was a principal author.

First, we drew on our decades of individual and collaborative research on white supremacism in the United States from the 1920s to the present. Our published research includes multiple studies of white supremacist violence, culture, recruitment, leadership, radicalization processes, criminal involvement, and the processes whereby white supremacist members leave the movement.

Second, we drew on our knowledge from decades of studying the research of social scientists, information analysts, computer scientists, and other scholars and analysts on domestic extremism, white supremacism, and ideologically-focused violence.

Third, we reviewed relevant information distributed by white supremacist and allied groups, government and security agencies, and nonprofit organizations, as well as media reports and publicly available social media.

Fourth, we analyzed postings on Discord,2 an Internet-based platform that enables real-time voice, video, and text connections between users, before, during and after the August 2017 UTR events. See Appendix D (Glossary of Terms and Symbols). At the outset, we read every post made by the individual Defendants, all posts within the Channels identified as those of the Defendant organizations, and posts within Channels associated with UTR. We also analyzed individual posts in the larger context of discussions on the Discord platform and by comparing Defendant posts with posts by other Discord users. For our review of Discord postings, we used a social scientific research strategy designed to ensure that conclusions are based on what the data revealed rather than the researcher’s preconceptions. This strategy employed the strength of both logics of research design in modern social sciences, deduction and induction, to guide our searches on the Discord platform and our analysis of the posts that were generated in these searches.

Deductive strategies begin with existing knowledge, and seek to test, refine, or extend this knowledge. For example, prior studies of WSM culture have uncovered certain ways of talking, such as disguising the meaning of certain phrases to outsiders by structuring them as jokes, and the use of insider terms such as “1488” that have specific meanings within WSM culture. Previous research also has found that activities in the WSM are likely to be referenced in a specific vocabulary, such as “shoot,” “gun,” and “power.” We use our knowledge of this research to guide the selection of terms and phrases that we used to search the Discord platform. We also used a deductive strategy to analyze the posts generated by these searches of the Discord platform. Based on our research and our knowledge of the research of other scholars, we analyzed the meaning of terms, phrases, and symbols that are commonly used in the WSM. Thus, we initially interpreted a post of “1488” to refer jointly to the “14 words” of the white supremacist terrorist David Lane and the double 88 to mean “Heil Hitler” because “H” is the 8th letter of the alphabet. As discussed below, we conducted additional levels of contextual analyses of Discord postings which, at times, resulted in a modification of our initial interpretations.

Used alone, a deductive strategy will fail to search for information that was not found in prior studies. To ensure that we did not exclude information, and to ensure that we could elicit and assess posts from the Discord platform in a fair and neutral manner, we supplemented a deductive strategic approach with an inductive strategic approach. An inductive approach begins with the data rather than with prior interpretations, so the researcher can weigh evidence without having a preconception of its meaning. We used inductive strategies by conducting searches of the Discord platform without specifying a search term. We were able to do so by using the capabilities of Everlaw, the software platform on which the Discord materials were hosted, to do random searches by sampling a selected percentage of total results. These searches generated batches of posts across the Discord platform from a random set of persons on a random set of topics, thus allowing us to locate information that had not been selected in our deductive searches. We conducted inductive analyses by reading through entire discussion “Channels” on Discord, including both those related and those unrelated to UTR events. This allowed us to understand the broad discussions on these Channels and avoid placing undue importance on idiosyncratic posts.

We conducted 1,461 searches of posts made between May 12, 2016 to December 12, 2018, to develop an accurate understanding of trends in post content and frequency over time.3 We used random searches as well as keyword searches across the entire Discord platform produced in the lawsuit to understand how Defendants and their affiliates operated on that platform and how they and others discussed the UTR events on that platform. These searches produced tens of thousands of posts in both text and image form. As noted above, we conducted searches both comprehensively (e.g., all posts to certain specific servers on the platform and all posts by Defendants) and selectively (e.g., targeted searches by keyword) to provide information that could challenge our pre-existing ideas as well as information that might confirm our opinions.

Many Defendants and their affiliates relied on a feature in Discord in which messages can be exchanged privately between two or more individuals without being visible to others on the Discord platform – direct messaging (DM), sometimes termed private messaging. We searched broadly in the direct messaging files of Discord and read every private message between Defendants for whom we had Discord handles.

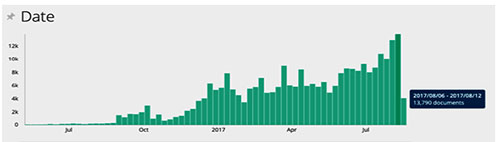

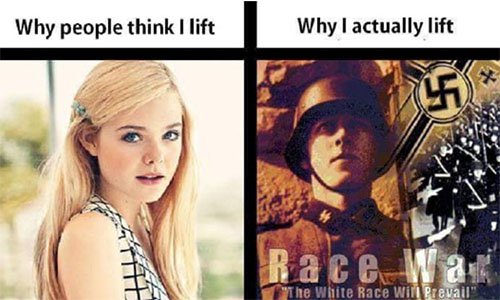

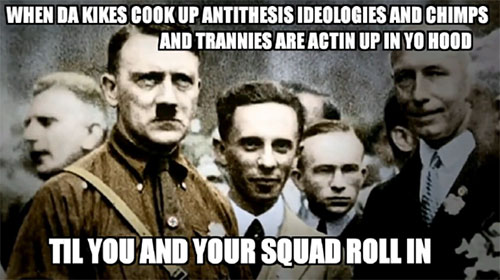

In addition to written posts, Discord had over 280,000 images posted between May 12, 2016, and August 14, 2017. We conducted a 1% random sample of all images, which produced 2,829 unique images. We also examined 1,411 images posted by Defendants. Defendants posted images at more than three times the rate of the average user data to which we had access (Defendant average = 202 images; all user average = 62 images). The largest number of images (13,790) were posted between August 6, 2017 and August 12, 2017, the period leading up to and including the 2017 UTR.

In total, we gathered and analyzed approximately 575,000 posts and direct messages from Discord. We made note of, and incorporated into this report, messages that appeared supportive of and counter to our overall findings.

Fifth, we examined documents made available to us by the Plaintiffs’ attorneys, including depositions of Defendants and third-party witnesses, and materials produced by Defendants and third-party witnesses. We analyzed these to assess their meaning and significance in the context of other information we have reviewed and our knowledge of and expertise on the WSM.4

Sixth, we took several additional measures to address the qualitative research protocol that researchers need to consider evidence that is potentially disconfirming (i.e., that does not support one’s initial hypotheses or presuppositions). We did so in part by using the standard social science technique of excluding irrelevant evidence to avoid distorting our results. Thus, when we searched the Discord platform for posts that, for example, encouraged Discord participants to be “careful” in their posting (which might be an indication of hiding violent messages), we individually assessed the relevance of each post generated by the search and excluded those in which the term “careful” had a different or ambiguous meaning. In addition, as noted above, we deliberately sought to locate information that potentially disconfirmed our initial suppositions by employing both inductive and deductive approaches in our analysis. And we elicited and considered potentially disconfirming information by considering all information in context. This was done by comparing posts by Defendants and their co-conspirators with posts by other users of Discord and by reading through entire Channels of Discord. We also added context by using both first-level (prima facie, or surface) analysis and second-level (contextual) analysis.

First-level analysis was used when the message of a written post or image was clear, as for example, the World War II-era German Nazi image with the caption “Get In Loser We’re Invading Charlottesville!” that was posted by Robert “Azzmador” Ray. Second-level analysis was done when the meaning of a posted message or image was less clear. In these cases, we examined individual posts within the sequence of posts that preceded and followed it on Discord. This generated sequences in which we could discern whether a post was responding to an earlier post, making a statement, or initiating a new series of posts. Such sequences allowed us to more precisely ascertain the meaning of individual posts. By examining Discord data across a fifteen-month period, we were able to discern trends in the sequences of posts and to avoid any distortions in meaning that might arise if we had focused exclusively on the period immediately prior to the 2017 UTR events. Thus, we are confident that our conclusions are based on the information we reviewed rather than our preconceptions.

2. The Concept of Culture Frames This Report

Culture is a central concept in the social sciences, and the organizing principle of this report. Social scientists define culture as the shared beliefs, values, language, understandings, practices and norms of behavior that create a sense of collective meaning and identity. Culture is generally studied by examining communications and the dynamics of interactions among individuals and groups.5

Culture operates on two levels: interpretive and behavioral. On the interpretive level, cultures transmit beliefs, norms, identities, and understandings over time and across generations through songs, stories, language, and symbols. Those immersed in a common culture tend to develop shared interpretations that inform their beliefs, values, and understandings. On the behavioral level, cultures establish a collective sense of approval for certain types of behavior. This type of approval is referred to as prescriptive, expressed in norms or guidelines that encourage specific behaviors while proscriptive norms discourage other behaviors. Thus, those immersed in a common culture tend to develop shared practices and a common understanding of collective norms of behavior. For this report, we describe interpretive and behavioral outcomes of culture separately, although in actuality these operate in intersecting and mutually reinforcing ways. Adopting the interpretive values and beliefs of a culture shapes how people behave. At the same time, aligning one’s behavior to others in a group intensifies one’s commitment to collective interpretations.

By creating shared interpretations and behaviors, cultures integrate. On the interpretative level, cultural practices of food, music, religion, and stories such as those found in Greek food festivals, Italian feast day processions, and St. Patrick’s Day events not only celebrate the ethnic roots of Americans but also create shared meanings about what it means to be Greek-American, Italian-American, or Irish- American. On the behavioral level, cultural norms press toward behaviors that distinguish a group - for example, as respectable fans of a sports team, or practitioners of a particular religion - and that create a sense of solidarity and collective identity. Behaviors like wearing modest clothing, tailgating at a team’s game, and displaying religious items bind individuals together. Cultures also create a sense of belonging. Expected behaviors, values and norms are expressed in “cultural scripts” whose meaning is accessible only to insiders.6 For example, collective cultural rituals - group practices that evoke strong emotions and often a sense of transcending ordinary existence,7 such as conversion ceremonies - regulate or pattern the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of their participants in subsequent situations.8 Its integrative nature allows a culture to evolve over time as persons connected to a particular culture repeatedly influence other individuals’ ideas and decisions.

By creating shared interpretations and behaviors, cultures also divide. Cultures create boundaries between those in the group and those on the outside of the group. Such distinctions are often quite benign, as in the cultural identities that might emerge in groups of professional cooks or residents of Iowa who share a sense of themselves as a group different from, but not hostile to, those outside the group. However, some cultural distinctions are decidedly antagonistic, as when cultural identities denote insiders as superior or safe and outsiders as inferior or dangerous. Such antagonist distinctions can fuel violence and even genocide, as happened in Nazi Germany and, more recently, in the civil war in Rwanda. Cultural rituals, such as those of commemoration of historical victories or atrocities, can transmit intergroup hostility across generations and prolong or incite new conflicts, as witnessed in violent episodes of the late 20th century such as those in Northern Ireland, India, the former Yugoslavia, and Turkey.9

Although cultural norms of interpretation and behavior regulate voluntary action, they are not deterministic. People are not simply passively shaped by their culture, as evidenced by the fact that two people exposed to the exact same cultural norm may respond differently. At the same time, a strong collective consensus supportive of certain beliefs or action clearly increases the likelihood that these will occur. Culture thus produces tendencies for how individuals will think and act but does not guarantee that every individual will do so in an identical manner.

Two social science concepts explain the seeming-paradox that culture exerts a powerful force on individual interpretation and behavior at the same time that individuals within a culture respond differently. One is the concept of subculture. Although people in a nation have a general common culture as, for example, the American cultural value of individualism, there are multiple subcultures within the nation. Beliefs, norms, identities, practices, and understandings differ in the U.S. across its multiple subcultures, from very broad subcultures such as Southern, urban, evangelical, or Asian- American, to very specialized subcultures such as rugby fans, mothers of triplets, or country music singers.10 The second is the concept of the cultural tool kit.11 Although people are highly influenced by cultural and subcultural norms and expectations, how any single individual will respond is analogous to how a carpenter chooses a tool to use for a specific job. That is, people selectively draw on the cultural and subcultural tools that are available to them to make decisions about how they will think and act, as well as to justify their interpretations and behavior. Depending on their location in multiple subcultures, people carry different cultural tool kits, for example, language and traditions, that they can use in any particular situation.

B. The White Supremacist Movement Exhibits a Set of Core Characteristics

The modern WSM in the United States is often described in terms of its four historical branches: the Ku Klux Klans (KKK or the Klan), Christian Identity sects, neo-Nazis, and white power skinheads. These branches have somewhat differing ideological emphases that reflect their roots in the historical KKK and U.S. neo-Nazism, but all embrace and have defended violence as a tactic to achieve a society in which the white race is completely dominant. The KKK is the oldest, and historically the most influential, branch of the WSM with origins that date to the multiple terroristic gangs formed after the Civil War that inflicted violence on former slaves and their white allies in the post-Civil War South. The Klan is not a singular organization; in every era of its existence, multiple Klan groups vied for power and members. More recent Christian Identity (CI) sects trace their roots to nineteenth century British Israelism. CI radically reinterprets the Bible to assert that whites are the true “children of Israel” and thus God’s chosen people; that nonwhites are not fully human but were created outside the line of descent from Adam and are hence “mud people”; and that Jews are the literal descendants of Satan. A third branch, U.S. neo-Nazis, emerged from the American Nazi Party after World War II and emphasizes the racial purity ideology of Adolf Hitler. White power skinheads, the fourth branch, emerged in the U.S. during the 1980s as an outgrowth of British youth subcultures in the post-World War II era.12

There is considerable overlap and connections among the four branches of the WSM, so distinctions among them are often blurred and individuals may have simultaneous affiliations with different groups. Any single group may use symbols or rituals from across the different branches as, for instance, a KKK chapter or a neo-Nazi group that exploits both Christian symbols favored by the KKK and Nordic mythological symbols associated with Nazi beliefs. From the 1980s, there has been increasing overlap among the four branches of the WSM with the rise of umbrella groups, such as the Aryan Nations (AN) that sought to unify Klan members, white power skinheads, and others around Nazi ideologies, and intensely violent white supremacist paramilitary groups such as Atomwaffen.13 Periodic efforts to unify the WSM through umbrella groups have rarely been successful for long, so the WSM is coordinated primarily through a common culture that sustains a shared set of interpretations and norms of behavior.

1. The WSM is Characterized by a Racist Ideology Based on White Supremacism, Anti- Semitism and Hostility Toward Immigrants, Social Minorities, and Feminism

White supremacist14 culture shapes the ideological understandings of its members by circulating white supremacist ideas in the form of statements, memes, pictures, songs, humor, chants, documents, website links, historical references and other messaging modes through its communication venues and networks. Spreading across the WSM are its core racist beliefs - such as denying that the Holocaust of European Jews happened and asserting that individuals of African descent are culturally and/or genetically inferior to whites. WSM culture also provides a platform to spread and amplify racist commentaries on current issues such as crime or school integration and for discussion of strategies to achieve the WSM goal of a future in which nonwhites and others designated as enemies of the white race have been exterminated, expelled, separated from or fully subordinated to the white race.

WSM culture does not simply indoctrinate its participants with racist ideas and agendas. It builds on - and intensifies - the boundaries that all cultures create between insiders and outsiders. It shapes a sense of participants as cultural insiders who share a common knowledge and way of interpreting the world. Consistent with how group cultures work more broadly, WSM culture provides insiders with clues on how to interpret its messages and ways of speaking. Consistent with how group cultures work more broadly, these messages are only interpretable to insiders. The circulation and explanation of a multitude of a constantly evolving set of referents - words, themes, memes, images, symbols, and codes - signal and reinforce shared meanings among movement insiders.

Some referents that circulate through WSM culture are explicit, with a meaning that is clear to both movement insiders and the wider public. Swastikas, for example, are commonly used to refer to state-run genocide in Hitler’s Nazi Germany. Many referents are less explicit, to ensure that the shared meanings of WSM culture are available to insiders but not understood in the same way by outsiders. An example is the use of “14” to reference the “14 words” of David Lane, a member of a white supremacist terrorist group, The Order, that was responsible for the 1984 murder of Denver talk show host Alan Berg and a $3.6 million robbery of an armored car. Lane’s “14 Words” (“We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White children”) have penetrated widely throughout the WSM culture, initially through the circulation of Lane’s writings and now by circulation through social media and other WSM communication venues.

2. The WSM is Characterized by a Radical Division Between Insiders and Outsiders

Lacking a central command structure, the WSM is organized through a deliberately created common culture that sustains a shared ideology of beliefs and goals grounded in an extreme differentiation between in-groups (whites/white supremacists) and out-groups (nonwhites/enemies) and an emphasis on violence. WSM culture is carried through multiple communication venues and networks that have varied over time and across locales. In the modern WSM, these include a vast array of white supremacist and related Internet websites and discussion forums, social media platforms, and podcasts, as well as in-person connections at white supremacist events, groups, and gatherings.

The culture of the WSM is fundamentally racist, a term used in social science to mean the general doctrine that one’s own race is superior and often accompanied by intergroup hatred and discrimination. The specific racism of WSM culture is a mix of ideologies based on white superiority, nonwhite inferiority, anti-black racism, hatred of Jews (anti-Semitism),15 animus toward immigrants and nonwhite foreigners, and hostility to sexual/gender minorities and feminism.16

WSM culture is both consistent and dynamic. Its fundamental ideologies of racism and central focus on violence have remained consistent over time. But particular aspects of WSM racist ideologies continually evolve as those connected to the culture repeatedly influence each other’s ideas through personal contacts and shared immersion in communication platforms. For example, anti-Semitism in the sectors of the WSM has evolved over time from more general stereotypes of Jews as greedy to, with the influence of Christian Identity, a sense of Jews as evil spawns of Satan.

3. The WSM is Highly Decentralized, Yet Coordinated

The WSM - now as in the past - is highly decentralized. The WSM is constituted by overlapping networks, groups, and associated individuals without an overarching organization, authority, board of directors or central command structure although some individual groups, such as KKKs or the National Socialist Movement, have leadership hierarchies. But its overall decentralization does not imply a lack of coordination. Even as the WSM is not a unified organization governed by a single centralized authority, certain individuals have particular influence within and across networks and groups. In this fashion, the WSM has intentionally adopted an organizational style in which much of its leadership emerges across individuals in different situations rather than, as in conventional organizations, being generally exercised in a top-down fashion across a hierarchy of formal positions. The deliberate creation of a WSM leadership structure that does not require official titles and in which different individuals emerge as leaders depending on circumstances makes it challenging for law enforcement to identify those who are directing violent actions by movement participants. But the movement’s lack of an overall centralized command structure does not mean that the WSM is disorganized or incapable of having influence. Decentralized movements that lack clear-cut command structures can have a powerful influence on individual-level interpretation and behavior by exerting pressure through a common cultural framework.17 Indeed, studies of social networks show that decentralized networks can shape collective action by nurturing a pool of believers oriented toward shared objectives and a common means of accomplishing these objectives.18 The organizational structure of the WSM is decentralized, but the movement’s culture is integrated with substantial agreement on core ideas and goals which allows the WSM to reinforce norms of violence and more general codes of conduct among its participants.

4. The WSM is Characterized by a High Degree of Internal Conflict

Despite broad agreement in the WSM about ideas and goals, the movement has historically been characterized by a high degree of internal friction and conflict. Internal conflicts within social movements are common, but they are especially prominent in the WSM. WSM leaders are typically self-proclaimed, often prompting internal struggles over who can rightfully claim the mantle of leadership. The decentralized organization of the WSM also provokes dissension among factions of the movement, even those with similar goals and ideologies, who may disavow each other or engage in intense struggle, and violence, against members of another group or network. Despite such cleavages, the common culture of the WSM binds leaders and members together in an understanding that all sectors will fight together in what white supremacists have long asserted is a coming race war, a vast near-apocalyptic clash between whites and nonwhites. These internal conflicts thus operate like the adage about family conflicts, that brothers may not see “eye to eye” but will still “fight side by side” when “push comes to shove.”19 In contrast, the WSM is highly suspicious of outsiders, fueled by its history of episodes of covert surveillance and infiltration by informants and undercover agents and of members who inform law enforcement about movement activities.20

5. The WSM Utilizes New Communication Technologies

The WSM was among the first social movements to take full advantage of the possibilities of the Internet as a communication and networking tool.21 New technologies of social media and Internet platforms allowed white supremacists a level of anonymity that facilitated their ability to recruit and communicate among members and interested individuals while evading detection.22 A new generation of some white supremacists and their groups have even used these communicative technologies to rebrand white supremacism as an acceptable form of politics by creating radically different strategic messaging to audiences of movement insiders, potential recruits, and the general public.

The use of computer technologies to create and sustain the WSM began as early as 1984 with the development of two electronic bulletin boards: the Liberty Bell, created by former Hitler Youth member George Dietz, and, shortly after, the Aryan Nations Liberty Net, led by decorated Vietnam War veteran Louis Beam who eventually became even more well known for his essay promoting a looser structure for the WSM and lone actor terrorism. The first message on the Aryan Nations Liberty Net underscores how Louis Beam and others in the WSM envisioned computer technology aiding their cause:

“Finally, we are all going to be linked together at one point in time… Imagine, if you will, all the great minds of the patriotic Christian movement linked together and joined into one computer. Imagine any patriot in the country being able to call up and access these minds… You are online with the Aryan Nations brain trust. It is here to serve the folk.”23

Liberty Bell and Liberty Net were followed less than a year later by white supremacist leader Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance (WAR) announcement of the development of their “WAR Computer Terminal” which ran on a Commodore-64. A decade after that, in 1995, Don Black’s Stormfront became the first major white supremacist website and communication tool; by the late 1990’s, thousands of white supremacist websites could be found across the World Wide Web. While the types of technology available have certainly changed, the proclivity among white supremacists to use this technology to enhance their effectiveness is nothing new.24

6. The WSM Utilizes Double-Speak

In addition to coded words and symbols, the WSM circulates and relies upon an insider mode of communicating that we term “double-speak” - language intended to deceive and to convey multiple meanings. Double-speak is a method of conveying white supremacist beliefs and intentions to those within the WSM culture while sending an innocuous meaning to outsiders. It is a communication style that relies on deception and often the use of euphemistic words designed to sidestep a more candid mention of a harsh or distasteful reality. It relies on the audience’s ability to interpret the meaning of a message in multiple ways, drawing on both their cognitive abilities and the understandings that are specific to the culture and subcultures in which they are embedded.25

Double-speak is a strategy intended to simultaneously reveal and conceal meaning embedded in words and to create plausible deniability for ideas or actions that would attract legal or social sanctions. An example is the circulation of images that refer to pre-Christian Nordic religions, such as Thor’s hammer, that are intended to signal an innocuous reference to ancient spiritual traditions to outsiders. Cultural insiders, however, will recognize such images as associated with sectors of white supremacism that adopt traditions of ancient Aryan spirituality.26 Another example is Pepe, an anthropomorphic green frog meme. Within modern WSM culture, there is considerable evidence from messages exchanged on white supremacist communication forums that the image of Pepe is exploited repeatedly to signify the ideas of racism and anti-Semitism; outside of white supremacism, Pepe lacks those connotations.

https://www.adl.org/education/references/hate-symbols/pepe-the-frog

It was in Answer to Job that the theology first articulated in Liber Novus -- the themes of the progressive incarnation of the God, the necessity for "Christification," and the replacement of the one-sided Christian God image with one that encompassed evil within it -- found its definitive expression and elaboration. In Jung's fantasies during World War I, a new God had been born in his soul, the God who is the son of the frogs, the son of the earth: Abraxas.Abraxas is the God who is difficult to grasp. His power is greatest, because man does not see it. From the sun he draws the summum bonum; from the devil the infinum malum; but from Abraxas LIFE, altogether indefinite, the mother of good and evil.

Jung saw this figure as representing the uniting of the Christian God with Satan, and hence as depicting a transformation of the Western God-image:

I understood that the new God would be in the relative. If the God is absolute beauty and goodness, how should he encompass the fullness of life, which is beautiful and hateful, good and evil, laughable and serious, human and inhuman? How can man live in the womb of the God if the Godhead himself attends only to one-half of him?

Answer to Job is faithful to the force of Jung's theophany, now presented in the form of psychotheological and historical argument. On November 25, 1953, Jung wrote to Richard Hull that "the clouds of dust it has raised at times nearly suffocated me!" [8] To this day, the controversies around this work have not been stilled.

-- Answer to Job, by C.G. Jung

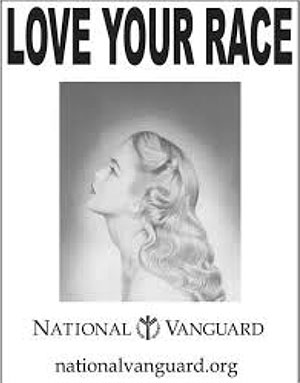

The “Love Your Race” campaign initiated in the early 2000’s by the neo-Nazi group, the National Alliance, is another example of double-speak. To its affiliates and members - as well as to potential recruits and enemies - “Love Your Race” was meant to be understood as a call for whites to stand up for their race against supposed threats by nonwhites. To outsiders, it was meant to signal simply love of one’s race, a common WSM defense against charges of racism.27

The image of the vulnerable white woman frequently appeared on “Love Your Race” campaign materials.28

The WSM strategy of double-speak goes beyond the use of expressions or symbols with multiple meanings. It operates on a broader level to create deception about the ideological and strategic direction of WSM groups and networks. An example is the recent WSM effort at rebranding that draws on its culture of double-speak in which thinly-veiled messages are meant to be read differently by separate audiences. Rebranding emerged in the current generation of white supremacists who built from the historical branches of the U.S. WSM to create their own organizations and networks that infused the ideologies of earlier white supremacism with new emphases. Although presenting themselves to outsiders as a new political movement, in our opinion, they are simply a contemporary version of a longstanding history of white supremacism in this country. Thus, we assess their organizational names, such as Identity Evropa (IE, now known as the American Identity Movement) and Patriot Front, as an organizational version of double-speak in which organizations are intentionally and strategically branded to appear to outsiders as fundamentally different from traditional white supremacist organizations to reduce stigma and appeal to mainstream populations. This strategy is evident in groups like IE that have sought to recruit college students with images of members in business suits and in the National Socialist Movement (NSM)’s decision to ban the public display of swastikas.29 Other white supremacist groups have also adopted this strategy by using relatively innocuous labels such as “patriot,” “ethno-nationalist,” and “alt-right” to blur the difference between white supremacism and mainstream conservative beliefs or ethnic pride to outsiders.30 To insiders, these groups display more traditional white supremacism.

In our opinion, the WSM strategy of rebranding has been a cosmetic overhaul - a double-speak - not an actual new approach to racial politics or a lessening in the extent of their racial extremism. Rebranding attempted to conceal from outsiders the WSM’s continuing promotion - largely in cultural arenas and events restricted to insiders - of the racial and religious hatred associated with earlier white supremacist groups. It tried to hide these groups’ continuing association with persons, symbols, and rituals of neo-Nazism and the KKK.31 And it helped to conceal the WSM’s advocacy of violence.

7. The WSM Focuses on Optics and Utilizes Front-Stage and Back-Stage Behavior

The WSM has historically emphasized the distinction between what behavior and messages should be displayed in public and what should be displayed in private. The social theorist Erving Goffman describes this as the distinction between “front-stage” and “back-stage” behavior: people present themselves differently when they are seeking to make an impression on others than they do in private.32

In our opinion, maintaining the separation between the front-stage and the back-stage is an essential feature of how the WSM works. White supremacist groups and platforms consistently operate to keep internal discussions and operations secret, restricted to back-stage places and to insiders and heavily guarded from outsiders. At the same time, they cultivate particular images to project to the public by monitoring the actions and messages that appear in front stage places that include outsiders. In recent years, discussions within the WSM have described its strategy of projecting a nonviolent and mainstream public image as “optics.” Robert Bowers, who contributed anti-Semitic posts on Gab, a social media platform frequented by white supremacists, added a final post before he allegedly entered a Pittsburgh synagogue to massacre 11 worshippers: “Screw your optics, I’m going in.”33

The WSM has implemented an optics strategy that pushes adherents to infiltrate mainstream society by selectively limiting overt displays of their allegiance to white supremacism. This strategy is parallel to the organizational rebranding strategy described above but, consistent with how group cultures work, is promoted and adopted by individuals. Starting in the 1990s, white supremacists were taught to live double lives: cover their racist tattoos, grow out their hair to avoid being identified as racist “skinheads,” hide extremist insignia, and outwardly project an image of non-extremism, especially to evade detection by law enforcement.34 WSM leaders promoted this approach as a means for white supremacists to secure positions of influence across a broad spectrum of society. In particular, the FBI has watched white supremacists quietly maintain an active presence in police departments and other law enforcement and military agencies. Infiltrating these institutions is strategic for the WSM because they provide tactical and weapons training that is useful in the violent furtherance of white supremacy. Other white supremacists nurture their hatred in seemingly benign, everyday settings such as family homes and Bible study groups where they create “free spaces” through music concerts, parties, outdoor events, and residential communities,35 and through the use of on-line and social media platforms in which they can share and develop their ideas among like-minded persons.36 For instance, in 2004, the neo-Nazi music label Panzerfaust (German Bazooka) attempted to distribute 100,000 CDs with hate-based music to teenagers, an effort they dubbed “Project Schoolyard USA.”37

[white power symbol] gotta take the whole city to church” 230

[white power symbol] gotta take the whole city to church” 230