The Silicon Valley Whipping Boycopyright 2015 PandoMedia Inc.

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

When I first read Alexis Madrigal’s ball-busting assault on the environmental ill-effects of Sean Parker’s forest wedding, I was appalled. I wanted to tweet the link to the Atlantic story with the comment “disgusting” or “Fuck you, Sean Parker,” just like some of my friends did. I like forests! People who hurt them are really shitty. So Madrigal’s descriptions, based on a report by the California Coastal Commission, were enough to rankle.

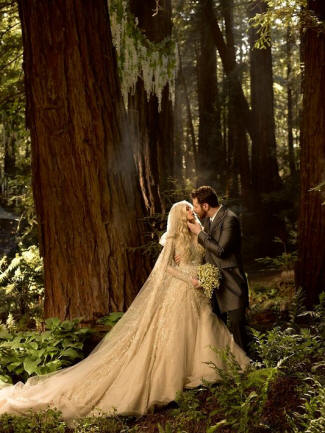

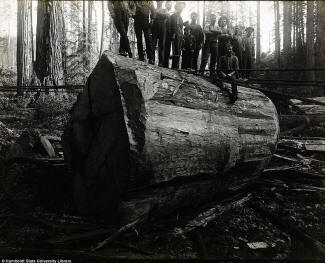

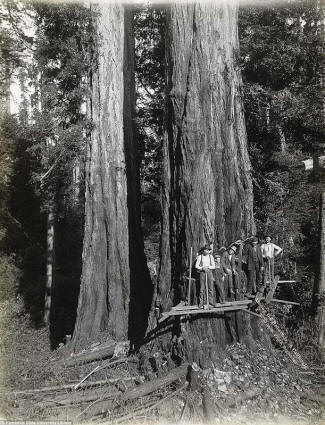

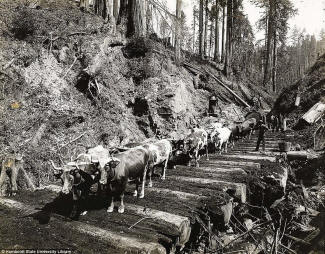

Parker, Madrigal charged, had cut a deal with a hotel to transform an ecologically sensitive area that used to be a campground into the backdrop for his gaudy wedding, replete with walls, water effects, and fake ruins – and all without a permit!

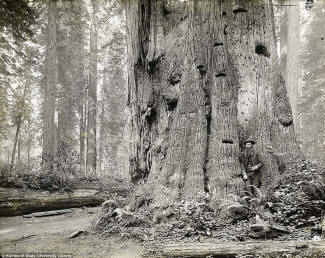

“Nothing says, ‘I love the Earth!’ quite like bringing bulldozers into an old-growth forest to create a fake ruined castle,” Madrigal wrote.

But then I thought, “I wonder how Sean Parker would have defended himself if he were given the opportunity.” Often, it turns out that stories such as these are more complicated than they first appear.

Of course, Parker wasn’t allowed a say. Instead, Madrigal, a reporter whose work I usually admire – the author of this wonderful history of a brick and this excellent elucidation of an under-acknowledged channel of information sharing – used his allegations against the Napster-founder-turned-early-Facebooker to support an argument that drew broader conclusions about the behavior of spoiled Silicon Valley frat-brats.

Calling Parker's wedding “grandstanding” that Valley pioneers Bob Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Bill Davidow would be ashamed of, Madrigal said:

But, of course, that's also part of the new Silicon Valley parable: dream big, privatize the previously public, pay no attention to the rules, build recklessly, enjoy shamelessly, invoke magic, and then pay everybody off.

So the problem went from being Sean Parker and his ostentatious ways to everything that was wrong with Silicon Valley. Parker’s apparent disregard for anything outside his selfish needs was, Madrigal suggested, consistent with a wider pattern of self-interested, spoiled brat behavior endemic to Valley culture.

The examples Madrigal cited are convincing enough. He pointed to the famous New Yorker profile on singularity-obsessed Peter Thiel; a Washington Post story about Uber’s disregard for legal considerations; a Fast Company story about Bill Nguyen’s reckless company-building; and a Nick Bilton column about over-the-top Silicon Valley parties. It's true that Thiel is a big dreamer. [Disclosure: Thiel is an investor in PandoDaily via the Founders Fund.] And yep, Uber is a shady player. PandoDaily contributor Paul Carr methodically disemboweled Uber founder Travis Kalanick on those grounds. And yeah, it’s right to call out Bill Nguyen for “failing up.” I wrote about a guy like that just the other day. Stupid Valley parties are also fair game – and I would like to add serving sushi on iPads to the list of deplorable party antics.

But for the rather more provocative “privatize the previously public” charge? Well, a link to an article that’s critical about the buses that Google uses to shuttle its employees to work is hardly evidence of sweeping privatization. The buses, actually, are stuffed with people who are pretty solidly middle class, and one of the reasons they exist is so they can support the “always on” work culture that these companies encourage. If you’re going to criticize anything about the buses, the mania for constant work should be it. It’s also notable that Google doesn’t have such buses in New York City, which has infinitely better transportation infrastructure than does spread-out Silicon Valley.

Nor is Madrigal’s claim that the Valley “invokes magic” well backed-up. The link he provides to support that claim leads to a Google search for the phrase “Silicon Valley magic” that throws up a few results with headlines written by people who are distinctly not Silicon Valley entrepreneurs.

I was left with the sense that Madrigal’s list of charges against Silicon Valley was included for reasons of poetry more than proof. It sounded good and on the surface seemed true. Indeed, commenters jumped in to cheer him on. “What did you expect from one of the people that foisted facebook on the world?” said one of the most upvoted comments. “Ayn Rand would applaud,” said another. For believers of the “Silicon Valley is a hive of festering narcissism and destruction” meme, the illusion of depth in Madrigal’s argument was more than enough to confirm their prejudices.

I don’t mean to pick on Madrigal’s piece. It simply stood out not only because of the emotive topic and controversial antagonist but also because of the timing. It comes on the heels of a spate of recent articles that have been highly critical of Silicon Valley culture. Joel Kotkin, writing for the Daily Beast, dedicated nearly 3,000 words to “Silicon Valley’s Shady 1 Percenters.” George Packer, in a New Yorker piece I have already argued was a bit skewed, described Valleyites as intellectually undeveloped and focused mainly on solving the problems of rich 20-year-olds. In February, Rebecca Solnit took aim at the Google bus, saying it sometimes seems like a face of “Janus-headed capitalism.” The bus, she said, contains “the people too valuable even to use public transport or drive themselves.”

There are entire blogs – ones that apparently make money – dedicated to chiding Silicon Valley. And of course, there’s “The Social Network,” Aaron Sorkin’s pièce de résistance about Valley excess and hubris. While the film is three years old now, and a work of fiction, it still seems to be the main source on which the general public base their opinions of Sean Parker.

I can sympathize with the Silicon Valley bashing. I’ve made fun of its douchey insider speak, mocked its hero culture, and bemoaned its “thought leader” bloviating. And trust me, I have no particular reason to defend the “new oligarchs” of the Valley. I am a New Zealander who lives in Baltimore. I have no aspirations to be part of the Silicon Valley world; I'm happy as an outsider.

But picking on the Valley is fun because it’s so easy, and because there’s ample material to draw on. Yammer CEO David Sacks threw a ridiculously lavish birthday party for himself with Snoop Lion as a guest performer. David Morin has daytime and nighttime iPhones. Tumblr CEO David Karp ended his announcement of the company’s $1.1 billion acquisition at the hands of Yahoo with a juvenile “Fuck yeah.” (He’s a New Yorker, but what the hell.) These are easy targets in the snark-infested waters of Internet commentary. And it’s hard to feel sorry for people who can afford three holiday homes before they turn 24, especially when they are overwhelmingly privileged white males.

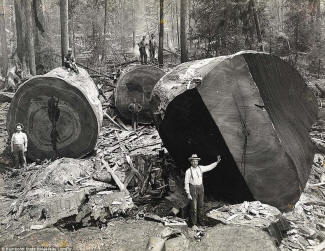

While it’s easy to mock the Valley, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the culture is intellectually shallow, that it has a tendency to privatize the previously public, or that it is basically just an extension of Sean Parker’s garish wedding in the Redwoods.

In his headline on the takedown piece, Madrigal says the wedding is “the Perfect Parable for Silicon Valley Excess.” That may sound good, but what if it’s not the perfect parable at all? What if Parker’s possibly destructive and totally excessive wedding was actually an exception? What if it just happened to be one of a small handful of examples that supported a pre-existing assumption that Silicon Valley is rotten with rich assholes who think only of themselves?

And what if turned out that the wedding wasn’t really that destructive? Wouldn’t that compromise the entire “parable of excess” thesis?

Parker is the perfect target. He’s a mega-rich bad boy, known for his benders and possible involvement in a drug scandal. He’s the guy who said the unutterably dorky line: “You know what’s cooler than a million dollars? One billion dollars.” Or at least, Justin Timberlake said that while playing Parker in “The Social Network,” but, you know, that’s him, right?

So I can understand why people would stand so ready to accuse Parker of ruining a Redwood forest just so he can have a pretty wedding. It’s fine to criticize him for how much money he spent on the wedding – reportedly the equivalent of a small company’s market cap – and for forming an LLC just for the event. But the man still deserves a fair defense. We would be doing ourselves an injustice if we let our half-informed views on Parker justify getting only one side of the story.

Well, on Thursday Parker was allowed to stage his defense. In a long letter that Madrigal published on The Atlantic’s website, Parker argued, convincingly, that his people left the site in better condition than what they found it in. Rather than being undisturbed forest, the site was covered in black asphalt, he claimed. He had also enlisted the help of the Save the Redwoods League, an organization to which he had previously contributed, to identify the site, which the adjacent hotel was contractually obliged to keep open on a for-profit basis. There was no “ruined castle.” The only stonework was hollow, filled with bird wire, and used for walkways and low walls.

Parker did admit, however, that “we made some mistakes” – which is open to interpretation – and he came off as a bit of a dick at the end of the letter when he tried to argue that the wedding wasn’t really that extravagant because it cost only $4.5 million rather than the rumored $9 million.

It must be said, then, that while Parker seems like the sort of guy we might not like to be friends with, he also doesn’t quite seem to be a forest-destroying cretin. So maybe his wedding isn’t a parable for Valley excess after all.

I have gone on at such tiresome length about this particular case, because it strikes me that the “lesson” being drawn from this Parker episode is similar to the lessons we are supposed to draw from other exceptional examples of Silicon Valley excess: the Sacks party, the Uber hubris, the outlandish parties. Rather than being seen as relatively isolated incidents that embarrass the wider community, they’re seen as emblematic of what must be some out-of-control partyland populated with assholes.

Okay, to some extent that’s true. I mean, sushi off iPads? Come on. But it’s just as true that Silicon Valley is filled with socially awkward programmers who rarely see daylight. It’s just as true that a lot of Valley entrepreneurs quietly work their asses off trying to build businesses that might one day create a lot of new jobs. It’s just as true that many people who live in the Valley also look at Parker’s over-the-top wedding and cringe.

What this particular example exposes is that there exists a very strong impulse to jump to conclusions about Silicon Valley that are colored by pre-existing biases. I would be tempted to argue, in fact, that Madrigal's article is the perfect parable for a wider phenomenon of people using half-baked facts and speculation as the basis for drawing inferences that support ossified views about subjects that are probably a great deal more complicated than they otherwise would have us believe.

The shame is that such populist attacks undermine the very valid criticisms of Silicon Valley – that shameful gender mix, for example, or its political naivety – that ought to be addressed but are also vulnerable to being dismissed as “Silicon Valley haterism.” I’m not trying to say that excess doesn’t exist in the Valley, and I’m not arguing for the Valley elite. I’m merely arguing for nuance.

These debates deserve a higher standard of rigor. It’s too easy to let it all devolve into a simplistic “us against Sean Parker” argumentative framework. It’s too easy to point at Travis Kalanick and shout, “Shady 1 Percenter!” and apply that one man’s actions to the rest of an entire region. It’s too easy to listen to only one side of the story.

Sometimes, after all, what at first looks like a ruined castle is just an empty prop.