From damage to discovery via virtual unwrapping: Reading the scroll from En-Gediby William Brent Seales, Clifford Seth Parker, Michael Segal, Emanuel Tov, Pnina Shor, and Yosef Porath

Science Advances

Vol 2, Issue 9

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1601247

21 Sep 2016

AbstractComputer imaging techniques are commonly used to preserve and share readable manuscripts, but capturing writing locked away in ancient, deteriorated documents poses an entirely different challenge. This software pipeline—referred to as “virtual unwrapping”—allows textual artifacts to be read completely and noninvasively. The systematic digital analysis of the extremely fragile En-Gedi scroll (the oldest Pentateuchal scroll in Hebrew outside of the Dead Sea Scrolls) reveals the writing hidden on its untouchable, disintegrating sheets. Our approach for recovering substantial ink-based text from a damaged object results in readable columns at such high quality that serious critical textual analysis can occur. Hence, this work creates a new pathway for subsequent textual discoveries buried within the confines of damaged materials.

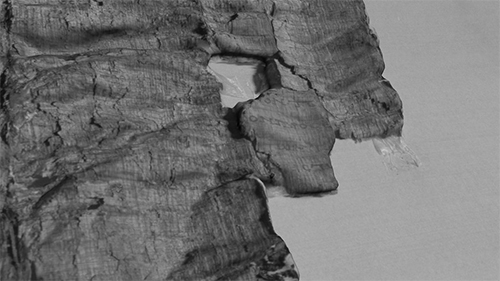

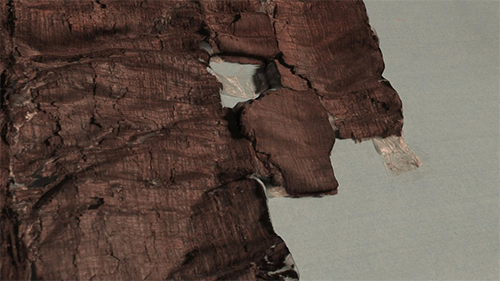

INTRODUCTIONIn 1970, archeologists made a dramatic discovery at En-Gedi, the site of a large, ancient Jewish community dating from the late eighth century BCE until its destruction by fire circa 600 CE. Excavations uncovered the synagogue’s Holy Ark, inside of which were multiple charred lumps of what appeared to be animal skin (parchment) scroll fragments (1, 2). The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) faithfully preserved the scroll fragments, although in the 40 years following the discovery, no one produced a means to overcome the irreversible damage they had suffered in situ. Each fragment’s main structure, completely burned and crushed, had turned into chunks of charcoal that continued to disintegrate every time they were touched. Without a viable restoration and conservation protocol, physical intervention was unthinkable. Like many badly damaged materials in archives around the world, the En-Gedi scroll was shelved, leaving its potentially valuable contents hidden and effectively locked away by its own damaged condition (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The charred scroll from En-Gedi. Image courtesy of the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, IAA. Photo: S. Halevi.

Fig. 1 The charred scroll from En-Gedi. Image courtesy of the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, IAA. Photo: S. Halevi.The implementation and application of our computational framework allows the identification and scholarly textual analysis of the ink-based writing within such unopened, profoundly damaged objects. Our systematic approach essentially unlocks the En-Gedi scroll and, for the first time, enables a total visual exploration of its interior layers, leading directly to the discovery of its text. By virtually unwrapping the scroll, we have revealed it to be the earliest copy of a Pentateuchal book ever found in a Holy Ark. Furthermore, this work establishes a restoration pathway for damaged textual material by showing that text extraction is possible while avoiding the need for injurious physical handling. The restored En-Gedi scroll represents a significant leap forward in the field of manuscript recovery, conservation, and analysis.

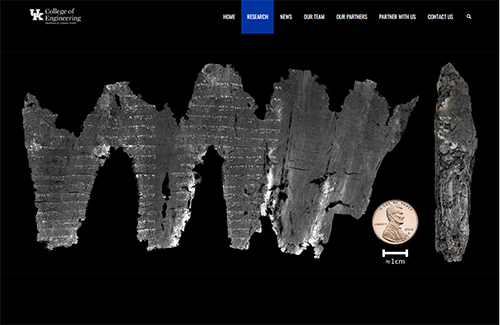

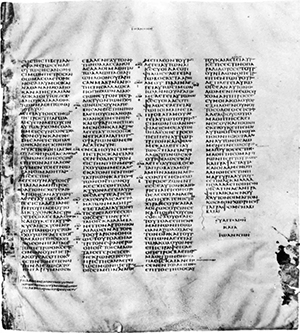

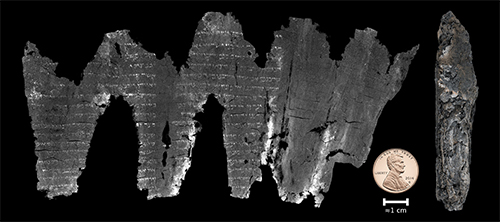

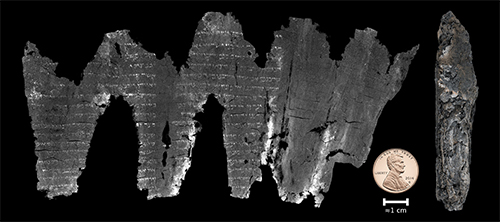

Virtual unwrappingOur generalized computational framework for virtual unwrapping applies to a wide range of damaged, text-based materials. Virtual unwrapping is the composite result of segmentation, flattening, and texturing: a sequence of transformations beginning with the voxels of a three-dimensional (3D) unstructured volumetric scan of a damaged manuscript and ending with a set of 2D images that reveal the writing embedded in the scan (3–6). The required transformations are initially unknown and must be solved by choosing a model and applying a series of constraints about the known and observable structure of the object. Figure 2 shows the final result for the scroll from En-Gedi. This resultant image, which we term the “master view,” is a visualization of the entire surface extracted from within the En-Gedi scroll.

Fig. 2 Completed virtual unwrapping for the En-Gedi scroll.

Fig. 2 Completed virtual unwrapping for the En-Gedi scroll.The first stage, segmentation, is the identification of a geometric model of structures of interest within the scan volume. This process digitally recreates the “pages” that hold potential writing. We use a triangulated surface mesh for this model, which can readily support many operations that are algorithmically convenient: ray intersection, shape dynamics, texturing, and rendering. A surface mesh can vary in resolution as needed and forms a piecewise approximation of arbitrary surfaces on which there may be writing. The volumetric scan defines a world coordinate frame for the mesh model; thus, segmentation is the process of aligning a mesh with structures of interest within the volume.

The second stage, texturing, is the formation of intensity values on the geometric model based on its position within the scan volume. This is where we see letters and words for the first time on the recreated page. The triangulated surface mesh offers a direct approach to the texturing problem that is similar to solid texturing (7, 8): Each point on the surface of the mesh is given an intensity value based on its location in the 3D volume. Many approaches exist for assigning intensities from the volume to the triangles of the segmented mesh, some of which help to overcome noise in the volumetric imaging and incorrect localization in segmentation.

The third stage, flattening, is necessary because the geometric model may be difficult to visualize as an image. Specifically, if text is being extracted, it will be challenging to read on a 3D surface shaped like the cylindrical wraps of scrolled material. This stage solves for a transformation that maps the geometric model (and associated intensities from the texturing step) to a plane, which is then directly viewable as a 2D image for the purpose of visualization.

In practice, this framework is best applied in a piecewise fashion to accurately localize a scroll’s highly irregular geometry. Also, the methodology required to map each of these steps from the original volume to flattened images involves a series of algorithmic decisions and approximations. Because textual identification is the primary goal of our virtual unwrapping framework, we tolerate mathematical and geometric error along the way to ensure that we extract the best possible images of text. Hence, the final merging and visualization step is significant not only for composing small sections into a single master view but also for checking the correctness and relative alignments of individual regions. Therefore, it is crucial to preserve the complete transformation pipeline that maps voxels in the scan volume to final pixels in the unwrapped master view so that any claim of extracted text can be independently verified.

The volumetric scanThe unwrapping process begins by acquiring a noninvasive digitization that gives some representation of the internal structure and contents of an object in situ (9–11). There are a number of choices for noninvasive, penetrative, and volumetric scanning, and our framework places no limits on the modality of the scan. As enhancements in volumetric scanning methodology [for example, phase-contrast microtomography (6, 12)] occur, we can take advantage of the ensuing potential for improved images. Whatever the scanning method, it must be appropriate to the scale and to the material and physical properties of the object.

Because of the particularities of the En-Gedi scroll, we used x-ray–based micro–computed tomography (micro-CT). The En-Gedi scroll’s damage creates a scanning challenge: How does one determine the correct scan protocol before knowing how ink will appear or even if the sample contains ink at all? It is the scan and subsequent pipeline that reveal the writing. After several calibration scans, a protocol was selected that produced a visible range of intensity variation on the rolled material. The spatial resolution was adjusted with respect to the sample size to capture enough detail through the thickness of each material layer to reveal ink if present and detectable. The chemical composition of the ink within the En-Gedi scroll remains unknown because there are no exposed areas suitable for analysis. However, the ink response within the micro-CT scan is denser than other materials, implying that it likely contains metal, such as iron or lead.

Any analysis necessitates physical handling of the friable material, and so, even noninvasive methods must be approached with great care. Although low-power x-rays themselves pose no significant danger to inanimate materials, the required transport and handling of the scroll make physical conservation and preservation an ever-present concern. However, once acquired, the volumetric scan data become the basis for all further computations, and the physical object can be returned to the safety of its protective archive.

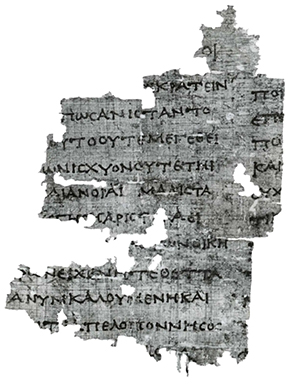

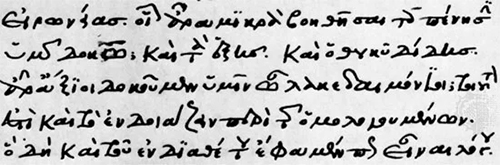

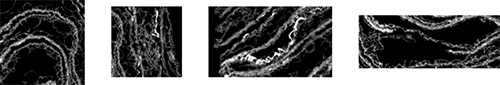

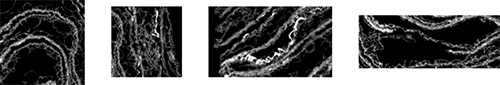

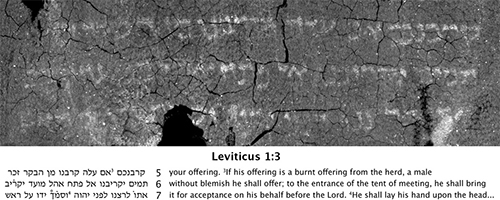

SegmentationSegmentation, which is the construction of a geometric model localizing the shape and position of the substrate surface within the scan on which text is presumed to appear, is challenging for several reasons. First, the surface as presented in the scanned volume is not developable, that is, isometric to a plane (13–15). Although an isometry could be useful as a constraint in some cases, the skin forming the layers of the En-Gedi scroll has not simply been folded or rolled. Damage to the scroll has deformed the shape of the skin material, which is apparent in the 3D scanned volume, making such a constraint unworkable. Second, the density response of animal skin in the volume is noisy and difficult to localize with methods such as marching cubes (16). Third, layers of the skin that are close together create ambiguities that are difficult to resolve from purely local, shape-based operators. Figure 3 shows four distinct instances where segmentation proves challenging because of the damage and unpredictable variation in the appearance of the surface material in the scan volume.

Fig. 3 Segmentation challenges in the En-Gedi scroll, based on examples in the slice view.

Fig. 3 Segmentation challenges in the En-Gedi scroll, based on examples in the slice view.

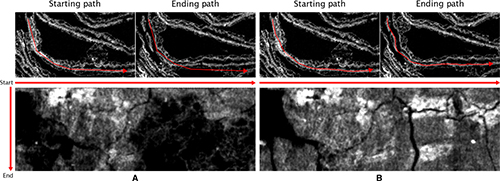

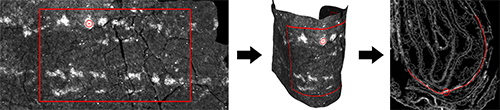

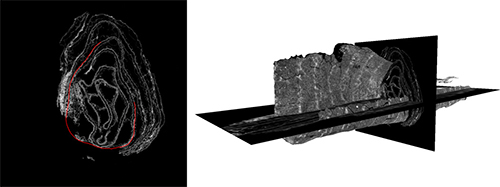

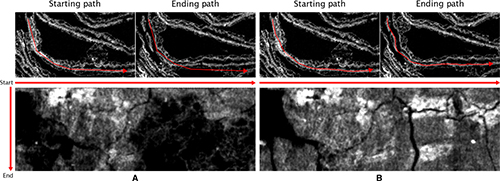

Double/split layering and challenging cell structure (left), ambiguous layers with unknown material (middle left), high-density “bubbling” on the secondary layer (middle right), and gap in the primary layer (right).Our segmentation algorithm applied to the En-Gedi scroll builds a triangulated surface mesh that localizes a coherent section of the animal skin within a defined subvolume through a novel region-growing technique (Fig. 4). The basis for the algorithm is a local estimate of the differential geometry of the animal skin surface using a second-order symmetric tensor and associated feature saliency measures (17). An initial set of seed points propagates through the volume as a connected chain, directed by the local symmetric tensor and constrained by a set of spring forces. The movement of this particle chain through the volume traces out a surface over time. Figure 5 shows how crucially dependent the final result is on an accurate localization of the skin. When the segmented geometry drifts from the skin surface (Fig. 5A), the surface features disappear. When the skin is accurately localized (Fig. 5B), the surface detail, including cracks and ink evidence, becomes visible.

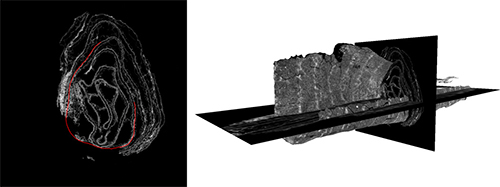

Fig. 4 A portion of the segmented surface and how it intersects the volume.

Fig. 4 A portion of the segmented surface and how it intersects the volume. Fig. 5 The importance of accurate surface localization on the final generated texture. (A) Texture generated when the surface is only partially localized. (B) Texture generated when surface is accurately localized.

Fig. 5 The importance of accurate surface localization on the final generated texture. (A) Texture generated when the surface is only partially localized. (B) Texture generated when surface is accurately localized.The user can tune the various parameters of this algorithm locally or globally based on the data set and at any time during the segmentation process. This allows for the continued propagation of the chain without the loss of previously segmented surface information. The segmentation algorithm terminates either at the user’s request or when a specified number of slices have been traversed by all of the particles in the chain.

The global structure of the entire surface is a piecewise composition of many smaller surface sections. Although it is certainly possible to generate a global structure through a single segmentation step, approaching the problem in a piecewise manner allows more accurate localization of individual sections, some of which are very challenging to extract. Although the segmented surface is not constrained to a planar isometry at the segmentation step, the model implicitly favors an approximation of an isometry. Furthermore, the model imposes a point-ordering constraint that prevents sharp discontinuities and self-intersections. The segmented surface, which has been regularized, smoothed, and resampled, becomes the basis for the texturing phase to visualize the surface with the intensities it inherits from its position in the volume.

TexturingOnce the layers of the scroll have been identified and modeled, the next step is to render readable textures on those layers. Texturing is the assignment of an intensity, “or brightness,” value derived from the volume to each point on a segmented surface. The interpretation of intensity values in the original volumetric scan is maintained through the texturing phase. In the case of micro-CT, intensities are related to density: Brighter values are regions of denser material, and darker values are less dense (18). A coating of ink made from iron gall, for example, would appear bright, indicating a higher density in micro-CT. Our texturing method is similar to the computer graphics approach of “solid texturing,” a procedure that evaluates a function defined over R3 for each point to be textured on the embedded surface (7, 8). In our case, the function over R3 is simply a lookup to reference the value (possibly interpolated) at that precise location in the volume scan.

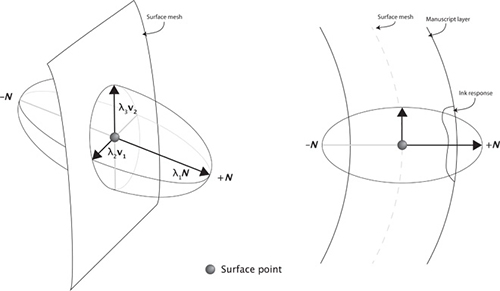

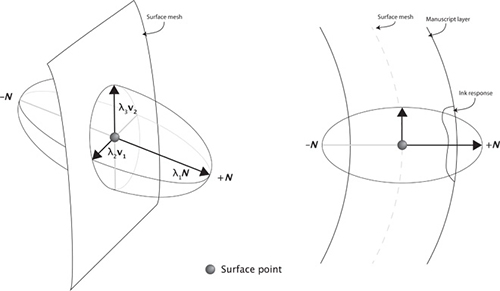

In an ideal case, where both the scanned volume and localized surface mesh are perfect, a direct mapping of each surface point to its 3D volume position would generate the best possible texture. In practice, however, errors in surface segmentation combined with artifacts in the scan create the need for a filtering approach that can overcome these sources of noise. Therefore, we implement a neighborhood-based directional filtering method, which gives parametric control over the texturing. The texture intensity is calculated from a filter applied to the set of voxels within each surface point’s local neighborhood. The parameters (Fig. 6) include use of the point’s surface normal direction (directional or omnidirectional), the shape and extent of the local texturing neighborhood, and the type of filter applied to the neighborhood. The directional parameter is particularly important when attempting to recover text from dual-sided materials, such as books. In such cases, a single segmented surface can be used to generate both the recto and verso sides of the page. Figure 7 shows how this texturing method improves ink response in the resulting texture when the segmentation does not perfectly intersect the ink position on the substrate in the volumetric scan.

Fig. 6 The geometric parameters for directional texturing.

Fig. 6 The geometric parameters for directional texturing. Fig. 7 The effect of directional texturing to improve ink response. (Left) Intersection of the mesh with the volume. (Right) Directional texturing with a neighborhood radius of 7 voxels.Flattening

Fig. 7 The effect of directional texturing to improve ink response. (Left) Intersection of the mesh with the volume. (Right) Directional texturing with a neighborhood radius of 7 voxels.FlatteningRegion-growing in an unstructured volume generates surfaces that are nonplanar. In a scan of rolled-up material, most surface fragments contain high-curvature areas. These surfaces must be flattened to easily view the textures that have been applied to them. The process of flattening is the computation of a 3D to 2D parameterization for a given mesh (6, 19, 20). One straightforward assumption is that a localized surface cannot self-intersect and represents a coherent piece of substrate that was at one time approximately isometric to a plane. If the writing occurred on a planar surface before it was rolled up, and if the rolling itself induced no elastic deformations in the surface, then damage is the only thing that may have interrupted the isometric nature of the rolling.

We approach parameterization through a physics-based material model (4, 21, 22). In this model, the mesh is represented as a mass-spring system, where each vertex of the mesh is given a mass and the connections between vertices are treated as springs with associated stiffness coefficients. The mesh is relaxed to a plane through a balanced selection of appropriate forces and parameters. This process mimics the material properties of isometric deformation, which is analogous to the physical act of unwrapping.

A major advantage of a simulation-based approach is the wide range of configurations that are possible under the framework. Parameters and forces can be applied per vertex or per spring. This precise control allows for modeling of not only the geometric properties of a surface but also the physical properties of that surface. For example, materials with higher physical elasticity can be represented as such within the same simulation.

Although this work relies on computing parameterizations solely through this simulation-based method, a hybrid approach that begins with existing parameterization methods [for example, least-squares conformal mapping (LSCM) (23) and angle-based flattening (ABF) (24)] followed by a physics-based model is also workable. The purely geometric approaches of LSCM and ABF produce excellent parameterizations but have no natural way to capture additional constraints arising from the mesh as a physical object. By tracking the physical state of the mesh during parameterization via LSCM or ABF, a secondary correction step using the simulation method could then be applied to account for the mesh’s physical properties.

Merging and visualizationThe piecewise nature of the pipeline requires a final merge step. There can be many individually segmented mesh sections that must be reconciled into a composite master view. The shape, location in the volume, and textured appearance of the sections aid in the merge. We take two approaches to the merging step: texture and mesh merging.

Texture merging is the alignment of texture images from small segmentations to generate a composite master view. This process provides valuable user feedback when performed simultaneously with the segmentation process. Texture merging builds a master view that gives quick feedback on the overall progress and quality of segmentation. However, because each section of geometry is flattened independently, the merge produces distortions that are acceptable as an efficiently computed draft view, but must be improved to become a definitive result for the scholarly study of text.

Mesh merging refers to a more precise recalculation of the merge step by using the piecewise meshes to generate a final, high-quality master view. After all segmentation work is complete, individual mesh segmentations are merged in 3D to create a single surface that represents the complete geometry of the segmented scroll. The mesh from this new merged segmentation is then flattened and textured to produce a final master view image. Because mesh merging is computationally expensive compared to texture merging, it is not ideal for the progressive feedback required during segmentation of a scan volume. However, as the performance of algorithms improves and larger segmented surfaces become practical, it is likely that mesh merging will become viable as a user cue during the segmentation process.

Maintaining a provenance chain is an important component of our pipeline. The full set of transformations used to generate a final master view image can be referenced so that every pixel in a final virtually unwrapped master view can be mapped back to the voxel or set of voxels within the volume that contributed to its intensity value. This is important for both the quantitative analysis of the resulting image and the verification of any extracted text. Figure 8 demonstrates the ability to select a region and point of interest in the texture image and invert the transformation chain to recover original 3D positions within the volume.

Fig. 8 Demonstration of stored provenance chain. The generated geometric transformations can map a region and point of interest in the master view (left) back to their 3D positions within the volume (right).RESULTS

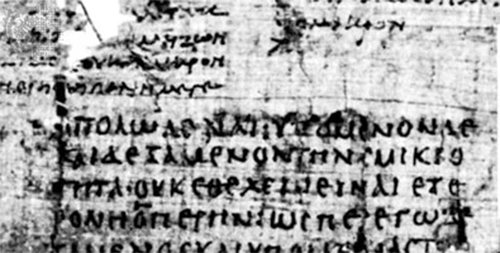

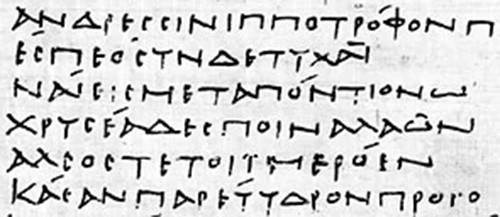

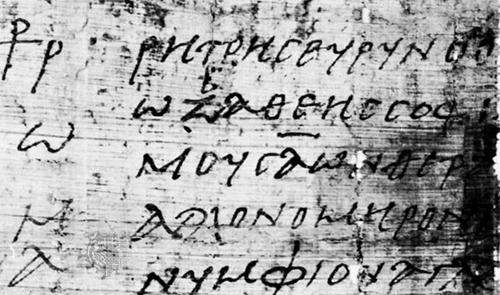

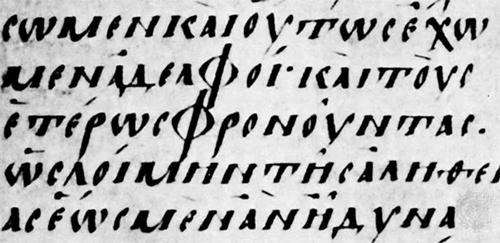

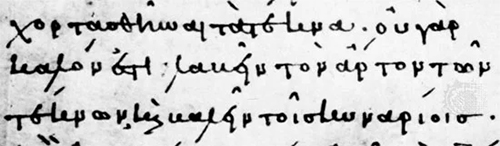

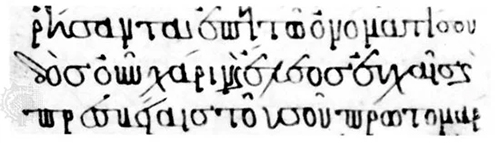

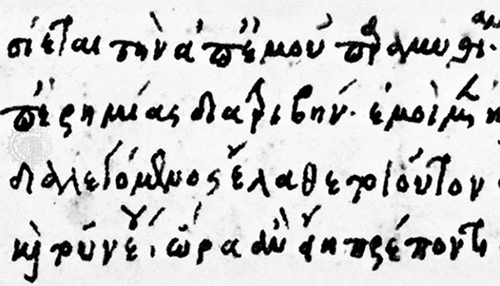

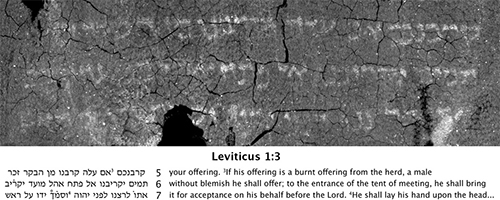

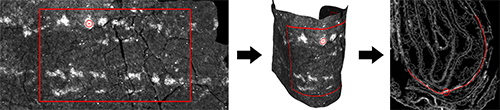

Fig. 8 Demonstration of stored provenance chain. The generated geometric transformations can map a region and point of interest in the master view (left) back to their 3D positions within the volume (right).RESULTSUsing this pipeline, we have restored and revealed the text on five complete wraps of the animal skin of the En-Gedi scroll, an object that likely will never be physically opened for inspection (Fig. 1). The resulting master image (Fig. 2) enables a complete textual critique, and although such analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, the consensus of our interdisciplinary team is that the virtually unwrapped result equals the best photographic images available in the 21st century. From the master view, one can clearly see the remains of two distinct columns of Hebrew writing that contain legible and countable lines, letters, and words (Fig. 9).

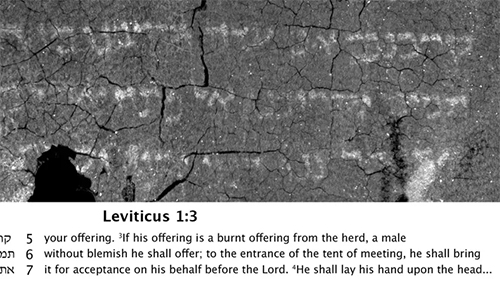

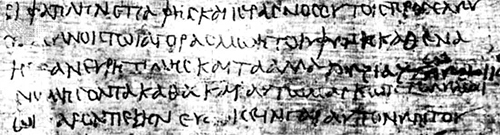

Fig. 9 Partial transcription and translation of recovered text. (Column 1) Lines 5 to 7 from the En-Gedi scroll.

Fig. 9 Partial transcription and translation of recovered text. (Column 1) Lines 5 to 7 from the En-Gedi scroll.These images reveal the En-Gedi scroll to be the book of Leviticus, which makes it the earliest copy of a Pentateuchal book ever found in a Holy Ark and a significant discovery in biblical archeology (Fig. 10). Without our computational pipeline and the textual analysis it enables, the En-Gedi text would be totally lost for scholarship, and its value would be left unknown.

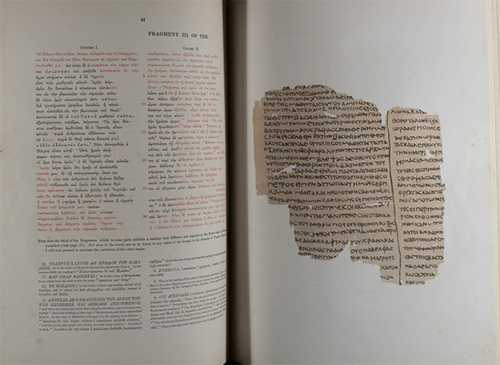

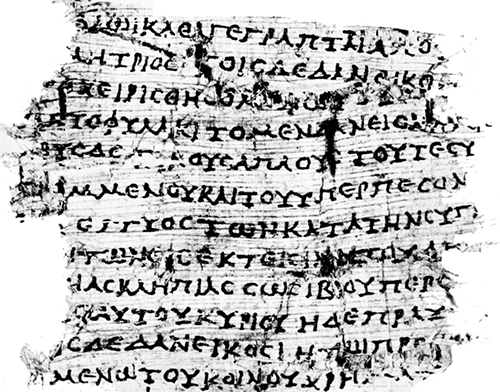

Fig. 10 Timeline placing the En-Gedi scroll within the context of other biblical discoveries.

Fig. 10 Timeline placing the En-Gedi scroll within the context of other biblical discoveries.What is clearly preserved in the master image is part of one sheet of a scripture scroll that contains 35 lines, of which 18 have been preserved and another 17 have been reconstructed. The lines contain 33 to 34 letters and spaces between letters; spaces between the words are indicated but are sometimes minimal. The two columns extracted from the scroll also exhibit an intercolumnar blank space, as well as a large blank space before the first column that is larger than the column of text. This large blank space leaves no doubt that what is preserved is the beginning of a scroll, in this case a Pentateuchal text: the book of Leviticus.

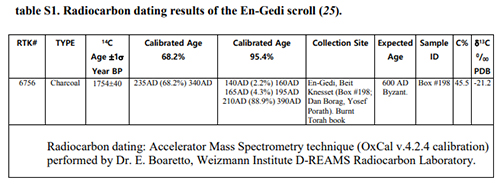

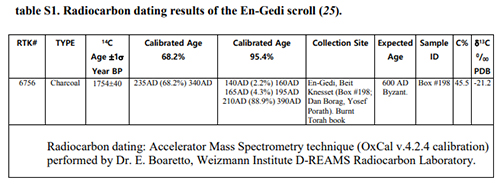

Armed with the extraction of this readable text and its historical context discerned from carbon dating and other related archeological evidence (1, 2), scholars can accurately place the En-Gedi writings in the canonical timeline of biblical text. Radiocarbon results date the scroll to the third or fourth century CE (table S1). Alternatively, a first or second century CE date was suggested on the basis of paleographical considerations by Yardeni (25). Dating the En-Gedi scroll to the third or fourth century CE falls near the end of the period of the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls (third century BCE to second century CE) and several centuries before the medieval biblical fragments found in the Cairo Genizah, which date from the ninth century CE onward (Fig. 10). Hence, the En-Gedi scroll provides an important extension to the evidence of the Dead Sea Scrolls and offers a glimpse into the earliest stages of almost 800 years of near silence in the history of the biblical text.

As may be expected from our knowledge of the development of the Hebrew text, the En-Gedi Hebrew text is not vocalized, there are no indications of verses, and the script resembles other documents from the late Dead Sea Scrolls. The text deciphered thus far is completely identical with the consonantal framework of the medieval text of the Hebrew Bible, traditionally named the Masoretic Text, and which is the text presented in most printed editions of the Hebrew Bible. On the other hand, one to two centuries earlier, the so-called proto-Masoretic text, as reflected in the Judean Desert texts from the first centuries of the Common era, still witnesses some textual fluidity. In addition, the En-Gedi scan revealed columns similar in length to those evidenced among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

DISCUSSIONBesides illuminating the history of the biblical text, our work on the scroll advances the development of textual imaging. Although previous research has successfully identified text within ancient artifacts, the En-Gedi manuscript represents the first severely damaged, ink-based scroll to be unrolled and identified noninvasively. The recent work of Barfod et al. (26) produced text from within a damaged amulet; however, the text was etched into the amulet’s thin metal surface, which served as a morphological base for the contrast of text. Although challenging, morphological structures provide an additional guide for segmentation that is unlikely to be present with ink-based writing. In the case of the En-Gedi scroll, for instance, the ink sits on the substrate and does not create an additional morphology that can aid the segmentation and rendering process. The amulet work also performed segmentation by constraining the surface to be ruled, and thus developable, to simplify the flattening problem. In addition, segmented strips were assembled showing letterforms, but a complete and merged surface segmentation was not computed, a result of using commercial software rather than implementing a custom software framework.

Samko et al. (27) describe a fully automated approach to segmentation and text extraction of undamaged, scrolled materials. Their results, from known legible manuscripts that can be physically unrolled for visual verification, serve as important test cases to validate their automated segmentation approach. However, the profound damage exhibited in the materials, such as the scroll from En-Gedi, creates its own new challenges—segmentation, texturing, and flattening algorithms—that only our novel framework directly addresses.

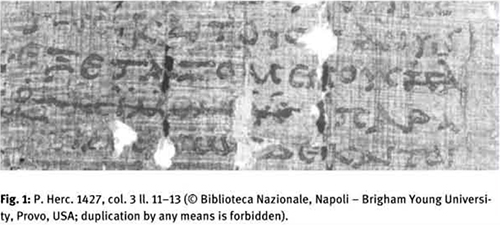

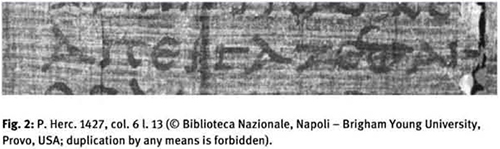

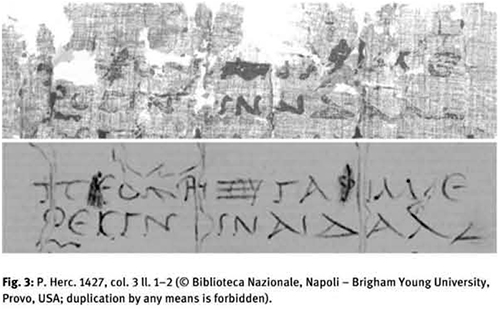

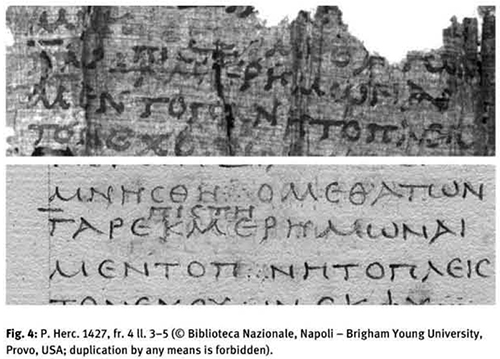

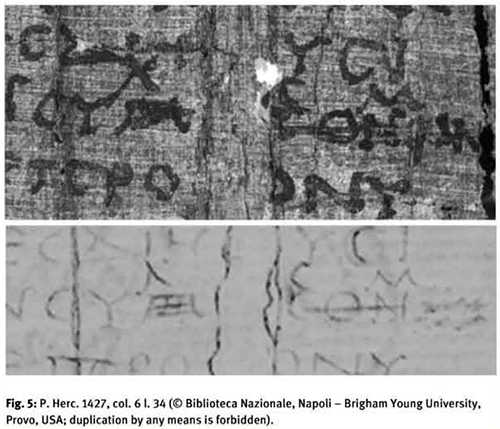

The work of Mocella et al. (12) claims that phase-contrast tomography generates contrast at ink boundaries in scans of material from Herculaneum. The hope for phase contrast comes from a progression of volumetric imaging methods (5, 6) and serves as a possible solution to the first step in our pipeline: creating a noninvasive, volumetric scan with some method that shows contrast at ink. Although verifying that ink sits on a page is not enough to allow scholarly study of discovered text, this is an important prelude to subsequent virtual unwrapping. Our complete approach makes such discovery possible.

An overarching concern as this framework becomes widely useful has to do not with technical improvements of the components, which will naturally occur as scientists and engineers innovate over the space of scanning, segmentation, and unwrapping, but rather with the certified provenance of every final texture claim that is produced from a scan volume. An analysis framework must offer the ability for independent researchers to confidently affirm results and verify scholarly claims. Letters, words, and, ultimately, whole texts that are extracted noninvasively from the inaccessible inner windings of an artifact must be subject to independent scrutiny if they are to serve as the basis for the highest level of scholarship. For such scrutiny to occur, accurate and recorded geometry, aligned in the coordinate frame of the original volumetric scan, must be retained for confirmation.

The computational framework we have described provides this ability for a third party to confirm that letterforms in a final output texture are the result of a pipeline of transformations on the original data and not solely an interpretation from an expert who may believe letterforms are visible. Such innate third-party confirmation capability reduces confusion around the resulting textual analyses and engenders confidence in the effectiveness of virtual unwrapping techniques.

The traditional approach of removing a folio from its binding—or unrolling a scroll—and pressing it flat to capture an accurate facsimile obviously will not work on fragile manuscripts that have been burned and crushed into lumps of disintegrating charcoal. The virtual unwrapping that we performed on the En-Gedi scroll proves the effectiveness of our software pipeline as a noninvasive alternative: a technological engine for text discovery in the face of profound damage. The implemented software components, which are necessary stages in the overall process, will continue to improve with every new object and discovery. However, the separable stages themselves, from volumetric scanning to the unwrapping and merging transformations, will become the guiding framework for practitioners seeking to open damaged textual materials. The geometric data passing through the individual stages are amenable to a standard interface through which the software components can interchangeably communicate. Hence, each component is a separable piece that can be individually upgraded as alternative and improved methods are developed. For example, the accurate segmentation of layers within a volume is a crucial part of the pipeline. Segmentation algorithms can be improved by tuning them to the material type (for example, animal skin, papyrus, and bark), the expected layer shape (for example, flat and rolled pages), and the nature of damage (for example, carbonized, burned, and fragmented). The flattening step is another place where improvements will better support user interaction, methods to quantify and visualize errors from flattening, and a comparative analysis between different mapping schemes.

The successful application of our virtual unwrapping pipeline to the En-Gedi scroll represents a confluence of physics, computer science, and the humanities. The technical underpinnings and implemented tools offer a collaborative opportunity between scientists, engineers, and textual scholars, who must remain crucially involved in the process of refining the quality of extracted text. Although more automation in the pipeline is possible, we have now achieved our overarching goal, which is the creation of a new restoration pathway—a way to overcome damage—to reach and retrieve text from the brink of oblivion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Master view resultsThe master view image of the En-Gedi scroll was generated using the specific algorithms and processes outlined below. Because we use the volumetric scan as the coordinate frame for all transformations in our pipeline, the resolution of the master view approximately matches that of the scan. The spatial resolution of the volume (18 μm/voxel, isometric) produces an image resolution of approximately 1410 pixels per inch (25,400 μm/inch), which can be considered archival quality. From this, we estimate the surface area of the unwrapped portion to be approximately 94 cm2 (14.57 in2). The average size of letterforms varies between 1.5 and 2 mm, and the pixels of the master view maintain the original dynamic range of 16 bits.

Volumetric scanTwo volumetric scans were performed using a Bruker SkyScan 1176 in vivo Micro-CT machine. It uses a PANalytical microfocus tube and a Princeton Instruments camera. With a maximum spatial resolution of 9 μm per voxel, it more than exceeded the resolution requirements for the En-Gedi scroll. A spatial resolution of 18 μm was used for all En-Gedi scans. Additionally, because this is an in vivo machine, the scroll could simply be placed within the scan chamber and did not need to be mounted for scanning. This limited the risk of physical damage to the object.

An initial, single field-of-view scan was done on the scroll to verify the scan parameters and to confirm that the resolution requirements had been met. This scan was performed at 50 kV, 500 μA, and 350-ms exposure time, with added filtration (0.2 Al) to improve image quality by absorbing lower-energy x-rays that tend to produce scattering. The reconstructions showed very clear separation of layers within the scroll, which indicated a good opportunity for segmentation. The scan protocol was then modified to increase contrast, where the team suspected that there may be visible ink. To acquire data from as much of the scroll as possible, the second and final scan was an offset scan using four connected scans. Final exposure parameters of 45 kV, 555 μA, and 230 ms were selected for this scan. The data were reconstructed using Bruker SkyScan’s NRecon engine, and the reconstructed slices were saved as 16-bit TIFF images for further analysis.

SegmentationThe basis for the algorithm is a local estimate of the differential geometry of the animal skin surface using a second-order symmetric tensor and associated feature saliency measures (17). The tensor-based saliency measures are available at each point in the volume. The 3D structure tensor for point p is calculated as

Jo(p)=gσ*∇u(p)∇u(p)T (1)

where ∇u(p) is the 3D gradient at point p, gσ is a 3D Gaussian kernel, and denotes convolution. The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of this tensor provide an estimate of the surface normal at p

n(p)=e1,ifλ1≫λ2≈λ3 (2)

The algorithm begins with an ordered chain of seed points localized to a single slice by a user. From the starting point, each particle in the chain undergoes a force calculation that propagates the chain forward through the volume. This region-growing algorithm estimates a new positional offset for each particle in the chain based on the contribution of three forces: gravity (a bias in the direction of the long axis of the scroll), neighbor separation, and the saliency measure of the structure tensor. First, n(p) is biased along the long axis of the scroll by finding the vector rejection of an axis-aligned unit vector Z onto n(p)

G=Z−Z⋅n(p)n(p)⋅n(p)n(p) (3)

To keep particles moving together, an additional restoring spring force S is computed using a spring stiffness coefficient k and the elongation factors Xl and Xr between the particle and both its left and right neighbors in the chain

S=−kXl+−kXr (4)

In the final formulation, a scaling factor α is applied to G, and the final positional offset for the particle is the normalized summation of all terms

ΔP=∥αG+S∥ (5)

The intuition behind this framework is the following: The structure tensor estimates a surface normal, which gives a hint at how a layer is moving locally through points (Eqs. 1 and 2). The layer should extend in a direction that is approximated locally by its tangent plane: the surface normal. The gravity vector nudges points along the major axis around which the surface is rolled, which is a big hint about the general direction to pursue to extend a surface. Moving outward, away from the major axis and across layers, generally defeats the goal of following the same layer. The spring forces help to maintain a constant spacing between points, restraining them from moving independently. These forces must all be balanced relative to one another, which is done by trial and error.

We applied the computed offset iteratively to each particle, resulting in a surface mesh sampled at a specific resolution relative to the time step of the particle system. The user can tune the various parameters of this algorithm based on the data set and at any time during the segmentation process. We also provided a feedback interface whereby a human user can reliably identify a failed segmentation and correct for mistakes in the segmentation process.

For each small segmentation, we used spring force constants of 0.5 and an α scaling factor of 0.3. Segmentation chain points had an initial separation of 1 voxel. This generally produced about six triangles per 100 μm in the segmented surface models. When particles crossed surface boundaries because the structure tensor did not provide a valid estimate of the local surface normal, the chain was manually corrected by the user.

TexturingTwo shapes were tested for the shape of the texturing neighborhood: a spheroid and a line. The line shape includes only those voxels that directly intersect along the surface normal. When the surface normal is accurate and smoothly varying, the line neighborhood allows parametric control for the texture calculation to incorporate voxels that are near but not on (or within) the surface. The line neighborhood leads to faster processing times and less blurring on the surface, although the spheroid neighborhood supports more generalized experimentation—the line neighborhood is a degenerate spheroid. We settled on bidirectional neighborhoods (voxels in both the positive and negative direction) using a line neighborhood with a primary axis length of 7 voxels. We filtered the neighborhood using a Max filter because the average ink response (density) in the volume was much brighter than the ink response of the animal skin.

FlatteningOur flattening implementation makes use of Bullet Physics Library’s soft body simulation, which uses position-based dynamics to solve the soft body system. Points along one of the long edges of the segmentation were pinned in place while a gravity force along the x axis was applied to the rest of the body. This roughly “unfurled” the wrapping and aligned the mesh with the xz plane. A gravity force along the y axis was then applied to the entire body, which pushed the mesh against a collision plane parallel to the xz plane. This action flattened the curvature of the mesh against the plane. A final expansion and relaxation step was applied to smooth out wrinkles in the internal mesh.

MergingIn total, around 140 small segmentations were generated during the segmentation process. These segmentations were then mesh-merged to produce seven larger segmentations, a little over one for each wrap of the scroll. Each large segmentation was then flattened and textured individually. The final set of seven texture images was then texture-merged to produce the final master view imagery for this paper. All merging steps for this work were performed by hand. Texture merges were performed in Adobe Photoshop, and mesh merging was performed in MeshLab. An enhancement curve was uniformly applied to the merged master view image to enhance visual contrast between the text and substrate.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank D. Merkel (Merkel Technologies Ltd.) who donated the volumetric scan to the IAA. Special thanks to the excavators of the En-Gedi site D. Barag and E. Netzer (Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem). Radiocarbon determination was made at the DANGOOR Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometer (D-REAMS) at the Weizmann Institute. We thank G. Bearman (imaging technology consultant, IAA.) for support and encouragement. W.B.S. acknowledges the invaluable professional contributions of C. Chapman in the editorial preparation of this manuscript. Funding: W.B.S. acknowledges funding from the NSF (awards IIS-0535003 and IIS-1422039). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF. W.B.S. acknowledges funding from Google and support from S. Crossan (Founding Director of the Google Cultural Institute). Author contributions: W.B.S. conceived and designed the virtual unwrapping research program. C.S.P. directed the software implementation team and assembled the final master view. P.S. acquired the volumetric scan of the scroll and its radiocarbon dating and provided initial textual analysis. M.S. and E.T. edited the visible text and interpreted its significance in the context of biblical scholarship. Y.P. excavated the En-Gedi scroll on May 5, 1970. The manuscript was prepared and submitted by W.B.S. with contributions from all authors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. All scan data and results from this paper are archived at the Department of Computer Science, University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY) and are available at

http://vis.uky.edu/virtual-unwrapping/engedi2016/.

Supplementary Material

Summary table S1. Radiocarbon dating results of the En-Gedi scroll (25).ResourcesFile (1601247_sm.pdf)REFERENCES AND NOTES

table S1. Radiocarbon dating results of the En-Gedi scroll (25).ResourcesFile (1601247_sm.pdf)REFERENCES AND NOTES1 D. Barag, En-Gedi: The synagogue, in New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, E. Stern, Ed. (Macmillan, 1993), pp. 405–409.

2 G. Hadas, Excavations at the Village of ‘En Gedi: 1993–1995. Atiqot 49, 136–137 (2005).

3 W. B. Seales, Y. Lin, Digital restoration: Principles and approaches, paper presented at the Proceedings of DELOS/NSF Workshop on Multimedia in Digital Libraries, Crete, Greece, 2003.

4 Y. Lin, W. B. Seales, Opaque document imaging: Building images of inaccessible texts, in Tenth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV’05) (IEEE, 2005).

5 W. B. Seales, J. Griffioen, D. Jacobs, Virtual conservation: Experience with micro-CT and manuscripts, in EIKONOPOIIA. Digital Imaging of Ancient Textual Heritage, V. Vahtikari, M. Hakkarainen, A. Nurminen, Eds. (Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, 2010), pp. 81–88.

6 W. B. Seales, D. Delattre, Virtual unrolling of carbonized Herculaneum scrolls: Research status (2007–2012). Cronache Ercolanesi 43, 191–208 (2013).

7 D. R. Peachey, Solid texturing of complex surfaces, in ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics (Association for Computing Machinery, 1985), pp. 279–286.

8 G. Turk, Texture synthesis on surfaces, in Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques (Association for Computing Machinery, 2001), pp. 347–354.

9 W. B. Seales, S. Crossan, Asset digitization: Moving beyond facsimile, in SIGGRAPH Asia 2012 Technical Briefs (Association for Computing Machinery, 2012), p. 32.

10 R. Baumann, D. C. Porter, W. B. Seales, The use of micro-CT in the study of archaeological artifacts, in 9th International Conference on NDT of Art, Jerusalem, Israel, 25 to 30 May 2008.

11 W. B. Seales, J. Griffioen, R. Baumann, M. Field, Analysis of Herculaneum papyri with x-ray computed tomography, in International Conference on Nondestructive Investigations and Microanalysis for the Diagnostics and Conservation of Cultural and Environmental Heritage, Florence, Italy, 2011.

12 V. Mocella, E. Brun, C. Ferrero, D. Delattre, Revealing letters in rolled Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast imaging. Nat. Commun. 6, 5895 (2015).

13 H.-Y. Chen, I.-K. Lee, S. Leopoldseder, H. Pottmann, T. Randrup, J. Wallner, On surface approximation using developable surfaces. Graph. Model Image Process. 61, 110–124 (1999).

14 G. Irving, C. Schroeder, R. Fedkiw, Volume conserving finite element simulations of deformable models. ACM Trans. Graph. 26, 13 (2007).

15 M. B. Amar, Y. Pomeau, Crumpled paper. Proc. R. Soc. London A 453, 729–755 (1997).

16 W. E. Lorensen, H. E. Cline, Marching cubes: A high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. ACM SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 21, 163–169 (1987).

17 G. Medioni, C.-K. Tang, M.-S. Lee, Tensor voting: Theory and applications, in Proceedings of RFIA, Paris, France, 2000.

18 G. T. Herman, Fundamentals of Computerized Tomography: Image Reconstruction From Projections (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, 2009).

19 M. S. Brown, W. B. Seales, Image restoration of arbitrarily warped documents. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 26, 1295–1306 (2004).

20 M. S. Brown, M. Sun, R. Yang, L. Yun, W. B. Seales, Restoring 2D content from distorted documents. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 29, 1904–1916 (2007).

21 W. B. Seales, Y. Lin, Digital restoration using volumetric scanning, in Proceedings of the 2004 Joint ACM/IEEE Conference on Digital Libraries (IEEE, 2004).

22 Y. Lin, Physically-Based Digital Restoration Using Volumetric Scanning (University of Kentucky, Lexington, 2007).

23 B. Lévy, S. Petitjean, N. Ray, J. Maillot, Least squares conformal maps for automatic texture atlas generation. ACM Trans. Graph. 21, 362–371 (2002).

24 A. Sheffer, B. Lévy, M. Mogilnitsky, A. Bogomyakov, ABF++: Fast and robust angle based flattening. ACM Trans. Graph. 24, 311–330 (2005).

25 A. Yardeni in M. Segal, E. Tov, W. B. Seales, C. S. Parker, P. Shor, Y. Porat, “An Early Leviticus Scroll from En Gedi: Preliminary Publication,” Textus 26, 2016.

26 G. H. Barfod, J. M. Larsen, A. Lichtenberger, R. Raja, Revealing text in a complexly rolled silver scroll from Jerash with computed tomography and advanced imaging software. Sci. Rep. 5, 17765 (2015).

27 O. Samko, Y.-K. Lai, D. Marshall, P. L. Rosin. Virtual unrolling and information recovery from scanned scrolled historical documents. Pattern Recognit. 47, 248–259 (2014).