by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/16/24

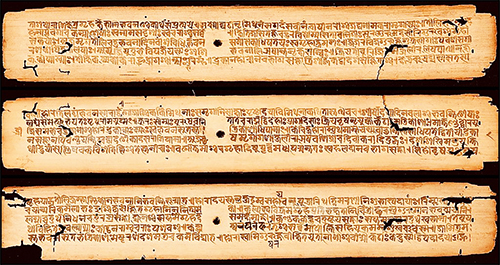

The Vendidad /ˈvendi'dæd/ or Videvdat or Videvdad is a collection of texts within the greater compendium of the Avesta. However, unlike the other texts of the Avesta, the Vendidad is an ecclesiastical code, not a liturgical manual.

Name

The name of the texts is a contraction of the Avestan language Vî-Daêvô-Dāta, "Given Against the Daevas (Demons)", and as the name suggests, the Vendidad is an enumeration of various manifestations of evil spirits, and ways to confound them. According to the divisions of the Avesta as described in the Denkard, a 9th-century text, the Vendidad includes all of the 19th nask, which is then the only nask that has survived in its entirety.

The Dēnkard or Dēnkart (Middle Persian: [x] "Acts of Religion") is a 10th-century compendium of Zoroastrian beliefs and customs during the time. The Denkard is to a great extent considered an "Encyclopedia of Mazdaism"[1] and is a valuable source of Zoroastrian literature especially during its Middle Persian iteration. The Denkard is not considered a sacred text by a majority of Zoroastrians, but is still considered worthy of study.

Name

The name traditionally given to the compendium reflects a phrase from the colophons, which speaks of the kart/kard, from Avestan karda meaning "acts" (also in the sense of "chapters"), and dēn, from Avestan daena, literally "insight" or "revelation", but more commonly translated as "religion." Accordingly, dēn-kart means "religious acts" or "acts of religion." The ambiguity of -kart or -kard in the title reflects the orthography of Pahlavi writing, in which the letter ⟨t⟩ may sometimes denote /d/.

Date and authorship

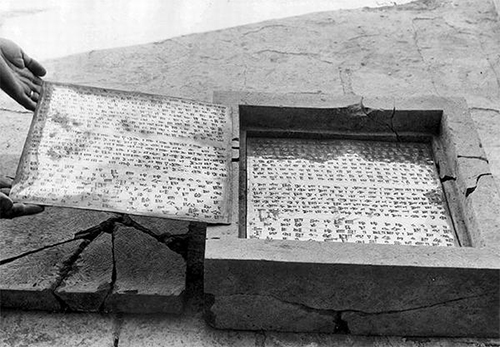

The individual chapters vary in age, style and authorship. Authorship of the first three books is attributed by the colophons to 9th-century priest Adurfarnbag-i Farrokhzadan, as identified in the last chapter of book 3. Of these three books, only a larger portion of the third has survived. The historian Jean de Menasce proposes that this survival was the result of transmission through other persons. The first three books were edited and in fact partially reconstructed, circa 1020, by a certain Ādurbād Ēmēdān of Baghdad, who is also the author of the remaining six books. The manuscript 'B' (ms. 'B 55', B for Bombay) that is the basis for most surviving copies and translations is dated 1659. Only fragments survive of any other copies.

The Denkard is roughly contemporary with the main texts of the Bundahishn.The Bundahishn (Middle Persian: Bun-dahišn(īh), "Primal Creation") is an encyclopedic collection of beliefs about Zoroastrian cosmology written in the Book Pahlavi script.[1] The original name of the work is not known. It is one of the most important extant witnesses to Zoroastrian literature in the Middle Persian language.

Although the Bundahishn draws on the Avesta and develops ideas alluded to in those texts, it is not itself scripture. The content reflects Zoroastrian scripture, which, in turn, reflects both ancient Zoroastrian and pre-Zoroastrian beliefs. In some cases, the text alludes to contingencies of post-7th century Islam in Iran, and in yet other cases, such as the idea that the Moon is farther than the stars.

Structure

The Bundahishn survives in two recensions: an Indian and an Iranian version. The shorter version was found in India and contains only 30 chapters, and is thus known as the Lesser Bundahishn, or Indian Bundahishn. A copy of this version was brought to Europe by Abraham Anquetil-Duperron in 1762. A longer version was brought to India from Iran by T.D. Anklesaria around 1870, and is thus known as the Greater Bundahishn or Iranian Bundahishn or just Bundahishn. The greater recension (the name of which is abbreviated GBd or just Bd) is about twice as long as the lesser (abbreviated IBd). It contains 36 chapters. The Bundahisn contains characteristics that fall under the rubric of different forms of classifications, including both as an encyclopedic text and as a text similar to midrash [expansive Jewish Biblical exegesis using a rabbinic mode of interpretation prominent in the Talmud.].

The traditionally given name seems to be an adoption of the sixth word from the first sentence of the younger of the two recensions. The older of the two recensions has a different first line, and the first translation of that version adopted the name Zand-Āgāhīh, meaning "Zand-knowing", from the first two words of its first sentence.

Most of the chapters of the compendium date to the 8th and 9th centuries, roughly contemporary with the oldest portions of the Denkard, which is another significant text of the "Pahlavi" (i.e. Zoroastrian Middle Persian) collection. The later chapters are several centuries younger than the oldest ones. The oldest existing copy dates to the mid-16th century.

The two recensions derive from different manuscript traditions, and in the portions available in both sources, vary (slightly) in content. The greater recension is also the older of the two, and was dated by West to around 1540. The lesser recension dates from about 1734.

Traditionally, chapter-verse pointers are in Arabic numerals for the lesser recension, and Roman numerals for the greater recension. The two series' are not synchronous since the lesser recension was analyzed (by Duperron in 1771) before the extent of the greater recension was known. The chapter order is also different.

Content

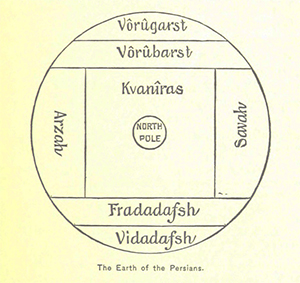

Regions depicted in chap. VIII (11) "On the nature of the lands": the Kvanîras (or Khvanîras) [North Pole], Savah, Arzah, Fradadafsh and Vîdadafsh, and Vôrûbarst and Vôrûgarst regions

The Bundahishn is the concise view of the Zoroastrianism's creation myth, and of the first battles of the forces of Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu for the hegemony of the world. According to the text, in the first 3,000 years of the cosmic year, Ahura Mazda created the Fravashis and conceived the idea of his would-be creation. He used the insensible and motionless Void as a weapon against Angra Mainyu, and at the end of that period, Angra Mainyu was forced to submission and fell into a stupor for the next 3,000 years. Taking advantage of Angra Mainyu's absence, Ahura Mazda created the Amesha Spentas (Bounteous Immortals), representing the primordial elements of the material world, and permeated his kingdom with Ard (Asha), "Truth" in order to prevent Angra Mainyu from destroying it. The Bundahishn finally recounts the creation of the primordial bovine, Ewagdad (Avestan Gavaevodata), and Keyumars (Avestan Keyumaretan), the primordial human.

Following MacKenzie,[3] the following chapter names in quotation marks reflect the original titles. Those without quotation marks are summaries of chapters that have no title. The chapter/section numbering scheme is based on that of B.T. Anklesaria[4] for the greater recension, and that of West[5] for the lesser recension. The chapter numbers for the greater recension are in the first column and in Roman numerals, and the chapter numbers for the lesser recension are in the second column, and are noted in Arabic numerals and in parentheses.

I. (1) The primal creation of Ohrmazd and the onslaught of the Evil Spirit.

I A. n/a "On the material creation of the creatures."

II. (2) "On the fashioning forth of the lights."

III. n/a "On the reason for the creation of the creatures, for doing battle."

IV. (3) "On the running of the Adversary against the creatures."

IV A. (4) The death of the Sole-created Bovine.

V. (5) "On the opposition of the two Spirits."

V A. n/a "On the horoscope of the world, how it happened."

V B. n/a The planets.

VI. n/a "On the doing battle of the creations of the world against the Evil Spirit."

VI A. (6) "The first battle the Spirit of the Sky did with the Evil Spirit."

VI B (7) "The second battle the Water did."

VI C. (8) "The third battle the Earth did."

VI D. (9) "The fourth battle the Plant did."

VI E. (10) "The fifth battle the Sole-created Ox did."

VI F. n/a "The sixth battle Keyumars did."

VI G. n/a "The seventh battle the Fire did."

VI H. n/a "The 8th battle the fixed stars did."

VI I. n/a "The 9th battle the spiritual gods did with the Evil Spirit."

VI J. n/a "The 10th battle the stars unaffected by the Mixing did."

VII. n/a "On the form of those creations."

VIII. (11) "On the nature of the lands."

IX. (12) "On the nature of the mountains."

X. (13) "On the nature of the seas."

XI. (20) "On the nature of the rivers."

XI A. (20) "On particular rivers."

XI B. (21) The seventeen kinds of "water" (of liquid).

XI C. (21) The dissatisfaction of the Arang, Marv, and Helmand rivers.

XII. (22) "On the nature of the lakes."

XIII. (14) "On the nature of the 5 kinds of animal."

XIV. (15) "On the nature of men."

XIV A. n/a "On the nature of women."

XIV B. (23) On negroes.

XV. (16) "On the nature of births of all kinds."

XV A. (16) Other kinds of reproduction.

XVI. (27) "On the nature of plants."

XVI A. (27) On flowers.

XVII. (24) "On the chieftains of men and animals and every single thing."

XVII A. n/a On the inequality of beings.

XVIII. (17) "On the nature of fire."

XIX. n/a "On the nature of sleep."

XIX A. n/a The independence of earth, water, and plants from effort and rest.

XX. n/a On sounds.

XXI. n/a "On the nature of wind, cloud, and rain."

XXII. n/a "On the nature of the noxious creatures."

XXIII. n/a "On the nature of the species of wolf."

XXIV. (18-19) "On various things, in what manner they were created and the opposition which befell them."

XXIV. A-C. (18) The Gōkarn tree, the Wās ī Paṇčāsadwarān (fish), the Tree of many seeds.

XXIV. D-U. (19) The three-legged ass, the ox Haδayãš, the bird Čamroš, the bird Karšift, the bird Ašōzušt, the utility of other beasts and birds, the white falcon, the Kāskēn bird, the vulture, dogs, the fox, the weasel, the rat, the hedgehog, the beaver, the eagle, the Caspian horse, the cock.

XXV. (25) "On the religious year."

XXVI. n/a "On the great activity of the spiritual gods."

XXVII. (28) "On the evil-doing of Ahreman and the demons."

XXVIII. n/a "On the body of men as the measure of the world (microcosm)."

XXIX. (29) "On the chieftainship of the continents."

XXX. n/a "On the Činwad bridge and the souls of the departed."

XXXI. n/a "On particular lands of Ērānšahr, the abode of the Kays."

XXXII. n/a "On the abodes which the Kays made with splendor, which are called wonders and marvels."

XXXIII. n/a "On the afflictions which befell Ērānšahr in each millennium."

XXXIV. (30) "On the resurrection of the dead and the Final Body."

XXXV. (31-32) "On the stock and the offspring of the Kays."

XXXV A. (33) "The family of the Mobads."

XXXVI. (34) "On the years of the heroes in the time of 12,000 years."

-- Bundahishn, by Wikipedia

Structure and content

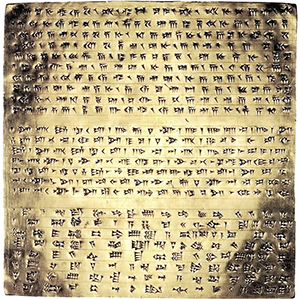

The Denkard originally contained nine books or volumes, called nasks, and the first two and part of the third have not survived. However, the Denkard itself contains summaries of nasks from other compilations, such as Chihrdad from the Avesta, which are otherwise lost....

Book 3

Book 3, with 420 chapters, represents almost half of the surviving texts. Jean de Menasce observes that there must have been several different authors at work, as the style and language of the collection is not uniform. The authors are however united in their polemic against the "bad religions", which they do not fail to identify by name (the prudent avoidance of any mention of Islam being an exception).

The majority of the chapters in book 3 are short, of two or three pages apiece. The topics covered in detail, though rare, frequently also identify issues for which the Zoroastrians of the period were severely criticized, such as marriage to next-of-kin (chapter 80). Although on first sight there appears to be no systematic organization of the texts in book 3, the chapter that deals with the principles of Zoroastrian cosmogony (Ch. 123) is the central theme around which the other chapters are topically arranged.

The last chapter of book 3 mentions two legends: one in which Alexander destroys a copy of the Avesta, and another in which the Greeks translate the Avesta into their own language.

Book 4

Book 4, the shortest (and most haphazardly organized) volume in the collection, deals primarily with the arts and sciences. Texts on those topics are interspersed by chapters explaining philosophical and theological concepts such as that of the Amesha Spentas, while other chapters deal with history and the religious contributions of Achaemenid and Sassanid monarchs.

Book 4 also contains an enumeration of works from Greece and India, and "reveals foreign influence from the 3rd century onward." The last chapter of Book 4 ends with a chapter explaining the necessity for practicing good thoughts, words and deeds, and the influences these have on one's afterlife.

Book 5

Book 5 deals specifically with queries from adherents of other faiths.

The first half of Book 5, titled the "Book of Daylamite", is addressed to a Muslim, Yaqub bin Khaled, who apparently requested information on Zoroastrianism. A large part of this section is summary of the history (from the Zoroastrian point of view) of the world up to the advent of Zoroaster and the impact of his revelations. The history is then followed by a summary of the tenets of the faith. According to Philippe Gignoux, the section "clearly nationalist and Persian in orientation, expressing the hope of a Mazdean restoration in the face of Islam and its Arab supporters."

The second half of Book 5 is a series of 33 responses to questions posed by a certain Bōxt-Mārā, a Christian. Thirteen responses address objections raised by Boxt-Mara on issues of ritual purity. The bulk of the remaining material deals with free will and the efficacy of good thoughts, words and deeds as a means to battle evil.

Book 6

Book 6 is a compilation of andarz (a literary genre, lit: "advice", "counsel"), anecdotes and aphorisms that embody a general truth or astute observation. Most of the compositions in book 6 are short didactic sentences that deal with morality and personal ethics.

Structurally, the book is divided into sections that are distinguished from one another by their introductory formulae. In the thematic divisions identified by Shaul Shaked, the first part is devoted to religious subjects, with a stress on devotion and piety. The second and third are related to ethical principles, with the third possibly revealing Aristotelian values. The fourth part may be roughly divided into sections with each addressing a particular human quality or activity. The fifth part includes a summary of twenty-five functions or conditions of human life, organized in five categories: destiny, action, custom, substance and inheritance. The fifth part also includes an enumeration of the names of authors that may have once been the last part of the book. In its extant form the book has a sixth part that, like the first part, addresses religious subjects.

Book 7

Book 7 deals [with] the "legend of Zoroaster", but which extends beyond the life of the prophet. The legend of Zoroaster as it appears in the Denkard differs slightly from similar legends (such as those presented in the contemporaneous Selections of Zadspram and the later Zardosht-nama) in that it presents the story of the prophet as an analogy of the Yasna ceremony.

The thematic and structural divisions are as follows:

1. The span of human history beginning with Kayomars, in Zoroastrian tradition identified as the first king and the first man, and ending with the Kayanid dynasty. This section of book 7 is essentially the same as that summarized in the first part of book 5, but additionally presents Zoroaster as the manifest representation of khwarrah (Avestan: kavaēm kharēno, "[divine] [royal] glory") that has accumulated during that time.

2. Zoroaster's parents and his conception.

3. Zoroaster's infancy and the vain attempts to kill him, through to Zoroaster's first communication with Ohrmuzd and the meeting with Good Thought, the Amesha Spenta Bahman (Avestan: Vohu Manah).

4. Zoroaster's revelation as received during his seven conversations with Ohrmuzd; the subsequent miracles against the daevas; the revival of the horse of Vishtasp (Avestan: Vistaspa) and the king's subsequent conversion; the vision of Zoroaster.

5. The life of Zoroaster from Vistasp's conversion up to Zoroaster's death, including his revelations on science and medicine.

6. The miracles that followed Zoroaster's death

7. The history of Persia until the Islamic conquest, with an emphasis on several historical or legendary figures.

8. Prophecies and predictions up to the end of the millennium of Zoroaster (that ends one thousand years after his birth), including the coming of the first savior and his son Ushetar.

9. The miracles of the thousand years of Ushetar until the coming of Ushetarmah.

10. The miracles of the thousand years of Ushetarmah until the coming of the Saoshyant.

11. The miracles of the fifty-seven years of the Saoshyant until the frashgird, the final renovation of the world.

Book 8

Book 8

Book 8 is a commentary on the various texts of the Avesta, or rather, on the Sassanid archetype of the Avesta. Book 8 is of particular interest to scholars of Zoroastrianism because portions of the canon have been lost and the Denkard at least makes it possible to determine which portions are missing and what those portions might have contained. The Denkard also includes an enumeration of the divisions of the Avesta, and which once served as the basis for a speculation that only one quarter of the texts had survived. In the 20th century it was determined that the Denkard's divisions also took Sassanid-era translations and commentaries into account; these were however not considered to be a part of the Avesta.

Book 9

Book 9 is a commentary on the Gathic prayers of Yasna 27 and Yasna 54. Together, these make up Zoroastrianism's four most sacred invocations: the ahuna vairya (Y 27.13), the Ashem Vohu (Y 27.14), the yenghe hatam (Y 27.15) and the airyaman ishya (Y 54.1).

-- Denkard, by Wikipedia

Content

The Vendidad's different parts vary widely in character and in age. Although some portions are relatively recent in origin, the subject matter of the greater part is very old. In 1877, Karl Friedrich Geldner identified the texts as being linguistically distinct from both the Old Avestan language texts as well as from the Yashts of the younger Avesta. Today, there is controversy over historical development of the Vendidad. The Vendidad is classified by some as an artificial, young Avestan text. Its language resembles Old Avestan. The Vendidad is thought to be a Magi (Magi-influenced) composition.[1] It has also been suggested that the Vendidad belongs to a particular school, but "no linguistic or textual argument allows us to attain any degree of certainty in these matters."[2]

Some consider the Vendidad a link to ancient early oral traditions, later written as a book of laws for the Zoroastrian community. [3] The writing of the Vendidad began - perhaps substantially - before the formation of the Median and Persian Empires, before the 8th century B.C.E.. [???!!!]

In addition, as with the Yashts, the date of composition of the final version does not exclude the possibility that some parts of the Vendidad may consist of very old material. Even in this modern age, Zoroastrians are continually rewriting old spiritual material. [???][4]

In addition, as with the Yashts, the date of composition of the final version does not exclude the possibility that some parts of the Vendidad may consist of very old material. Even in this modern age, we are continually rewriting old material.

-- Zoroastrian Heritage, by K. E. Eduljee

The first chapter is dualistic creation myth, followed by the description of a destructive winter. The second chapter recounts the legend of Yima (Jamshid). Chapter 19 relates the temptation of Zoroaster, who, when urged by Angra Mainyu to turn from the good religion, turns instead towards Ahura Mazda. The remaining chapters cover diverse rules and regulations, through the adherence of which evil spirits may be confounded. Broken down by subject, these fargards deal with the following topics (chapters where a topic is covered are in brackets):

• hygiene (in particular care of the dead) [3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 16, 17, 19] and cleansing [9,10];

• disease, its origin, and spells against it [7, 10, 11, 13, 20, 21, 22];

• mourning for the dead [12], the Towers of Silence [6], and the remuneration of deeds after death [19];

• the sanctity of, and invocations to, Atar (fire) [8], Zam (earth) [3,6], Apas (water) [6, 8, 21] and the light of the stars [21];

• the dignity of wealth and charity [4], of marriage [4, 15] and of physical effort [4]

• statutes on unacceptable social behaviour [15] such as breach of contract [4] and assault [4];

• on the worthiness of priests [18];

• praise and care of the bull [21], the dog [13, 15], the otter [14], the Sraosha bird [18], and the Haoma tree [6].

There is a degree of moral relativism apparent in the Vendidad, and the diverse rules and regulations are not always expressed as being mystical, absolute, universal or mandatory. The Vendidad is mainly about social laws, mores, customs and culture. In some instances, the description of prescribed behaviour is accompanied by a description of the penances that have to be made to atone for violations thereof. Such penances include:

• payment in cash or kind to the aggrieved;

• corporal punishment such as whipping;

• repeated recitations of certain parts of the liturgy such as the Ahuna Vairya invocation.

Value of the Vendidad among Zoroastrians

Most of the Zoroastrians continue to use the Vendidad as a valued and fundamental cultural and ethical moral guide, viewing their teachings as essential to Zoroastrian tradition and see it as part of Zoroastrianism original perspectives about the truth of spiritual existence. They argue that it has origins on early oral tradition, being only later written.[5][6][7]

The emergent reformist Zoroastrian movement reject the later writings in the Avesta as being corruptions of Zarathustra's original teachings and thus do not consider the Vendidad as an original Zoroastrian scripture. They argue that it was written nearly 700 years after the death of Zarathustra and interpret the writing as different from the other parts of the Avesta.[8]

An article by Hannah M. G. Shapero sums up the reformist perspective:[9]

"How do Zoroastrians view the Vendidad today? And how many of the laws of the Vendidad are still followed? This depends, as so many other Zoroastrian beliefs and practices do, on whether you are a "reformist" or a "traditionalist." The reformists, following the Gathas as their prime guide, judge the Vendidad harshly as being a deviation from the non-prescriptive, abstract teachings of the Gathas. For them, few if any of the laws or practices in the Vendidad are either in the spirit or the letter of the Gathas, and so they are not to be followed. The reformists prefer to regard the Vendidad as a document which has no religious value but is only of historic or anthropological interest. Many Zoroastrians, in Iran, India, and the world diaspora, inspired by reformists, have chosen to dispense with the Vendidad prescriptions entirely or only to follow those which they believe are not against the original spirit of the Gathas."

Liturgical use

Although the Vendidad is not a liturgical manual, a section of it may be recited as part of a greater Yasna service. Although such extended Yasnas appears to have been frequently performed in the mid-18th century (as noted in Anquetil-Duperron's observations), it is very rarely performed at the present day. In such an extended service, Visparad 12 and Vendidad 1-4 are inserted between Yasna 27 and 28. The Vendidad ceremony is always performed between nightfall and dawn, though a normal Yasna is performed between dawn and noon.

Because of its length and complexity, the Vendidad is read, rather than recalled from memory as is otherwise necessary for the Yasna texts. The recitation of the Vendidad requires a priest of higher rank (one with a moti khub) than is normally necessary for the recitation of the Yasna.

The Vendidad should not be confused with the Vendidad Sadé. The latter is the name for a set of manuscripts of the Yasna texts into which the Vendidad and Visperad have been interleaved. These manuscripts were used for liturgical purposes outside the yasna ceremony proper, not accompanied by any ritual activity. The expression sadé, "clean", was used to indicate that these texts were not accompanied by commentaries in Middle Persian.

See also

• Avesta

• Avestan geography

Notes

1. Zaehner, Richard Charles (1961). The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism. New York: Putnam. p. 160ff.

Portions of the book are available online.

2. Kellens, Jean (1989). "Avesta". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 35–44. p. 35

3. Ervad Marzban J. Hathiram. The significance and philosophy of the Vendidad Retrieved 14 January 2023

4. "Avestan, Iranian & Zoroastrian Languages". heritageinstitute.com.

5. "Importance of Vendidad in the Zarathushti Religion: By Ervad Behramshah Hormusji Bharda".

6. Ervad Marzban Hathiram Significance and Philosophy of the Vendidad Retrieved 14 January 2023

7. "Ranghaya, Sixteenth Vendidad Nation & Western Aryan Lands". http://www.heritageinstitute.com.

8. "AVESTA - The Scriptures of Zoroastrianism - Access New Age". March 18, 2021.

9. The Vendidad. The Law Against Demons Retrieved 14 January 2023

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Avesta/Vidēvdād

• Müller, Max, ed. (1880). "The Vendidad". The Zend-Avesta, Part I (SBE, vol. 4). Translated by Darmesteter, James. Oxford: OUP.

*******************

Vendidad: The Law Against Demons

by Hannah M.G. Shapero

7/5/95

The Vendidad is the latest book of the Avesta, the scriptures of Zoroastrianism. The word Vendidad is an evolution from "Vi- daevo-dato," which means "the law against demons." Through time this became "Videvdat," and then "Vendidad."

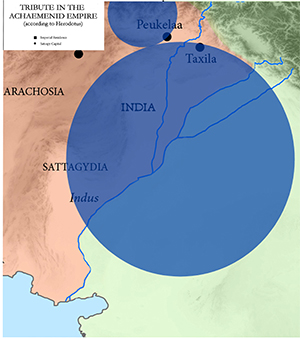

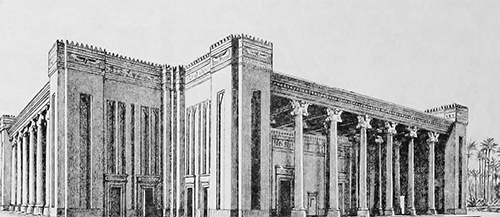

The Vendidad was written down between about 200 AD and 400 AD, either in the later years of the Parthian Empire or during the Sassanian Empire, the last Persian empire before the Islamic conquest. Even though its writing is late compared to the rest of the Avesta, the material it contains is much more ancient; some of it may date back to pre-Zarathushtrian times, and much of it comes from the age of the Magi, during the Achaemenid Persian Empire, 600-300 BC.

Most of the original Zoroastrian scriptures have been lost over the years due to destructive invaders such as Alexander, the Islamic Arabs, and the Mongols. The Avesta as it now stands consists of what was salvaged from these scriptures, saved in the memories of priests who kept the sacred words in oral tradition. The Vendidad is a late compilation of such material, probably set down in writing by many different authors and edited into one book.

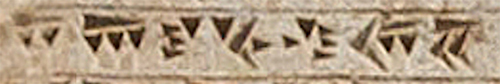

Unlike the poetry of the Gathas and the various hymns in the Avesta, the Vendidad is in prose, although it is a highly rhetorical prose. Its language is Avestan, the ancient Iranian language of the Gathas and other prayers, but it is a much later variant of Avestan. Some scholars have speculated that the Avesta of the Vendidad seems to be a priestly usage of a language that is no longer living, hence there are many grammatical "mistakes" and structural changes from the language of the earlier hymns composed when Avestan was still a living language.

Most of the book is set forth in a structure of questions proposed by Zarathushtra to Ahura Mazda, the Wise God, and Mazda's answers. The rhetorical pattern of questions and answers is typical of orally preserved literature, as it is an aid to memory. This does not necessarily mean that any of the material in the Vendidad comes directly from the Prophet or from Ahura Mazda, nor that the Prophet wrote the Vendidad. The priests who preserved the teachings composed their text in Zarathushtra's name, a very old strategy for giving a newer text ancient authority. The question of whether any of the material in the Vendidad is really from Zarathushtra is impossible to answer, as the scriptures that might have given an answer to this question have been lost. But the Gathas of Zarathushtra, the only part of the Avesta truly attributed to the Prophet, contain many of the "seeds" of the stories, lore, and ideas found in the Vendidad, and there is quite a lot of continuity in spirit, if not in letter, between these two documents composed almost two millennia apart [???].

To the natural difficulties which obstruct the progress of sound science in the East, we add great difficulties of our own making. Bounties and premiums, such as ought not to be given even for the propagation of truth, we lavish on false texts and false philosophy.

[url]-- Minute by the Hon'ble T. B. Macaulay, by Thomas Babington Macaulay, February 2, 1835[/url]

But there is a great difference between the psychological outlooks of the two documents. Though Zarathushtra is very much aware of the reality of divine beings both good and evil, he deals mostly with abstract concepts in his Gathas. He may personify the great Attributes of God, the Amesha Spentas, but even they are abstract: Righteousness, Devotion, Dominion. His evil concepts are equally abstract: Greed, Violence, Wrath, and especially Deceit, which in the Avestan language is called druj.

In the Vendidad, the abstractions have all been personified, or "concretized." There is a whole universe of good and evil entities between human beings and the transcendent God Ahura Mazda. It is the world of "cosmic" dualism, where both the earthly and heavenly worlds are gathered into conflicting camps of Good and Evil. The Attributes of God are now beings resembling archangels, and all the evil concepts have been personified as demons. This is especially true for the demon of Deceit, Druj. In the Vendidad, Druj is a hideous demon of pollution associated with corpses. The world of the Vendidad is a world filled with spirits and demons, which can be affected by ritual actions. We will visit this world when we come to the ritual and purification laws of the Vendidad.

The Vendidad contains different types of material, which can be classified as mythological tales, "wisdom-literature," legal texts for both civil and religious situations, formulaic prayers for exorcism and ritual usages, and what might be called a "technical manual" for priests conducting Zoroastrian rituals of invocation and purification. The text is divided into 22 "Fargards," or sections, each with sub-sections and numbered paragraphs.

The Vendidad opens with mythological tales, or sacred stories. Fargard I gives a catalog of sacred geography, in which various regions of ancient Iran are paired with the particular demon that attacks them; not only is this actual geography but a kind of map of the spirit world as well. Fargard II tells the story of King Yima, the pre-historic king of Iran. He was warned that a deadly Ice Age would come upon the earth, and was instructed by Ahura Mazda to build a Utopian community called a var, isolated from the rest of the world. Yima brought there perfect breeding samples of each species of plant and animal along with a perfect community of people. Here, protected from the dreadful ice, the best of Earth was preserved. This myth is so much like the myth of Noah's Ark that many scholars think it was influenced by the Semitic sacred story.

The Vendidad also ends with sacred stories: in Fargards 19,20, and 21 we read of the temptation of Zarathushtra by many demons, the story of Thrita, the first healer, who was given knowledge of surgery, herbal remedies, and sacred healing prayers by the Amesha Spenta Kshathra, and finally, more sacred geography about the passage of the heavenly bodies and the heavenly waters through the sky.

The wisdom-literature of the Vendidad is interspersed throughout the book. It contains sage instructions about what is best in life, what is worst in life, and what the pious Zarathushtrian should do. The Vendidad recommends agriculture and husbandry as the best work in life, and family life and good eating as the best way to live. It also extols the virtue of holy study, and vehemently rejects teachers of heretical or foreign creeds. This endorsement of family, fertility, and feasting, and the rejection of heresy, is thought to be a reaction to the world-denying preaching of rival religions such as Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Christianity, all of which value fasting and celibacy. Such religious challenges date from the Sassanian era (250-650 AD) and give a clue as to when those Vendidad passages might have been written.

Other sections of the Vendidad, such as Fargards 10 and 11, contain instructions for the reciting of sacred formulas, or manthras. In the religious culture of the Vendidad, as in current Zoroastrianism, prayers are recited in Avestan. Not many people, then or now, understand Avestan; by the time of the Vendidad, it was a forgotten language, remembered by rote, understood only through cloudy translations. But the idea of Avestan words, especially the Gathas, as holy texts, remained central to prayer. The prayers had power as holy words even when the person praying did not know the content of the prayer.

In our modern culture, heavily influenced by Protestant Christianity, we may find it hard to conceive of a religious practice in which an untranslated prayer formula has its own intrinsic power to reach God. A prayer, for us, is only effective if it is in a familiar language, and understood and believed by the praying person. The modern reformers of Zoroastrianism share this attitude, and have long voiced their distaste for a prayer practice that relies on rote ritual utterances. Yet this is the conception of manthra prayer in the Vendidad's ancient tradition. This was not the case in the much earlier Gathas, where the language and content of Avestan prayers was still very much alive and familiar to Zarathushtra's early followers. A verse from the Gathas, in the Vendidad, has the power to exorcise demons or heal sickness, irrespective of its content being understood. It is a kind of holy spell, a talismanic utterance. The Vendidad contains lists of the proper Avestan verses to say, and when they should be said. This is part of the "technical manual" aspect of the book.

The greatest part of the Vendidad is taken up with legal texts. Most of the civil law of the Avesta was in the books that are lost, but a fragment of civil law is preserved in Fargard 4. This section deals with the various types of contracts, oaths, and property agreements, and the punishments for breaking these contracts. It also enumerates the different degrees of assault, from verbal threats to murder, and states the punishment for each act of violence; the penalties depend on how grave the assault is and how many times it has been committed.

Fargards 13 and 14 deal with the treatment and breeding of dogs. This is somewhere between civil and religious law. Dogs are regarded as the holiest of animals, almost equal to people. This is a natural attitude among people whose livelihood depends on herds of cattle and sheep, where herding dogs are essential helpers. Dogs also have spiritual powers, as described in Fargard 8. The presence and gaze of a dog is said to drive away evil spirits, and a dog is brought to a corpse and to the places the corpse has been, to puritfy them. The dog is a protector in both the physical and the spiritual world.

The legal texts concerning dogs cite many different situations in which dogs might be injured, and the punishment for the injury. Other cases concern breeding mother dogs, raising puppies, and protection against rabid dogs. Other animals are also covered in the Vendidad text, though their identity is no longer clear to modern readers. The "water dog" (possibly an otter) is especially sacred, and the man who kills one of these creatures must undergo punishment so severe and burdensome that many scholars think it could never have literally been carried out.

The rest of the legal texts of the Vendidad are what could be considered the Zoroastrian code of canon law. These are religious rules which apply to priests, rituals, and most especially maintenance of ritual purity.

We in the West are unfamiliar with ritual purity, unless we are Orthodox Jews. This concept has been interpreted in many ways. Anthropologists like Mary Douglas, in her book PURITY AND DANGER, interpret purity as the maintenance of categories, roles, and boundaries in society. Other, more "materialistic" scholars view rules of purity and pollution as the hygienic and medical lore of a pre-technological society. The rules make sense in the light of modern hygiene, and are given religious sanctions to induce people to follow them. Many of the rules of purity and pollution in the Vendidad actually are proper hygiene by our modern standards, but other rules only make sense when interpreted by the pre-scientific thinking of their day.

Many reformist Zoroastrians question whether Zarathushtra ever intended purity laws to be part of his religion. There is only one ambiguous passage in the Gathas which could refer to purity, but there are certainly no prescriptions of purity practices in the Gatha hymns such as are found in the Vendidad. Scholars note that many of the purity laws of the Vendidad are identical or very close to purity laws followed by upper-caste Hindus, which suggests that they go back to the pre-historic time when Iranians and Indians were one people. But even if Zarathushtra's ancient Iranians did inherit some purity practices from their common past, the multiplication and complication of laws found in theVendidad are almost certainly later developments, probably due to the influence of the Magian priesthood of western Iran, who achieved power during the Achaemenid Empire (600-300 BC). They followed a strict priestly code of purity, which had not only Indo-Iranian elements but Semitic and Mesopotamian influence. This priestly code was later extended to the entire population, and thus a pervasive and complex purity practice, which may not have been in the original teachings of the Prophet, entered orthodox Zoroastrian life.

What does purity and pollution mean to Zoroastrians? One of the best references for this is a book by Jamsheed Choksy, a Parsi scholar who was able to attend purification rituals which are closed to non-Zoroastrians. In his book, PURITY AND POLLUTION IN ZOROASTRIANISM, he explains ritual purity in its religious, rather than social or hygienic context. In the great cosmic conflict between Good and Evil, the pure belong to God's side, and the polluted succumb to Ahriman, the Hostile Spirit. In Zoroastrianism, as Choksy states, there is continuity, not separation, between the physical and the spiritual. What is done for the physical world reflects into the spiritual world:

"The theological linking of the spiritual and material aspects of the universe in the Gathas forms the basis of every action. All thoughts, words, and deeds, can serve to further the cosmic triumph of Ahura Mazda over Angra Mainyu (Ahriman), righteousness over evil....Therefore, the purification rituals not only cleanse a believer's physical body but also are said to purify the soul, thereby assisting in the vanquishing of evil."

In the Vendidad, pollution can come from many sources. It may come from evil animals, known as khrafstras, which are part of Ahriman's creation: snakes, flies, ants, or destructive wolves. It may come from sickness, or from excrement, or from cast-off body waste such as cut hair or nails. Pollution also comes from women during their menstrual periods, a notion which is very common among pre-modern peoples all over the earth. The Vendidad contains detailed instructions (in Fargard 16) on how women should be isolated during their menses. But most of all, pollution comes from dead bodies: the corpses of humans and dogs, and this takes up the greatest amount of technical text in the document.

The pollution of a corpse is personified in the demonic Druj Nasu, the hideous, insect-like spirit of dead flesh. The Vendidad contains very detailed and elaborate instructions on how to protect against and purify human beings from polluting contact with corpses. The text also describes the dakhmas, the famous Towers of Silence where the bodies of dead Zoroastrians are placed to be consumed by vultures and other scavenger animals. Every possible contact with corpses is covered in almost obsessive detail: what to do if someone dies in wintertime and snow and ice prevent access to the Tower, what to do if you find the body of a drowned person in river or lake water, how much pollution happens if a man dies in public surrounded by people, and how to purify land, clothing, wood, vessels, or even houses which have been in contact with corpses. The text also describes the purification process for a woman who has had a miscarriage or a stillbirth; since she has carried a corpse within her, she is especially polluted.

Most of the purification rituals in the Vendidad consist of multiple baths or rubdowns with bull's urine, earth, and water, accompanied by the recital of the proper prayers. The most powerful ritual is the barashnom, a rite that lasts nine days and nights, in which the person to be purified is isolated in a special enclosure and bathed nine times with the sequence of bull's urine, dry earth, and water, as he moves through a series of sacred patterns and spaces laid out on the ground. This ritual can take away the pollution of close contact with corpses, but is reserved for serious occasions due to its length and complexity.

The laws of the Vendidad, both civil and religious, prescribe punishments as well as purifying rituals. Each infraction has a punishment specified for it, whether it is a matter of intentional violent crime or failure to observe the proper ritual laws. Most of the time, these punishments are corporal: they consist of a specified number of lashes with the aspahe-astra or horsewhip, and an equal number of lashes with an instrument called the sraosho-karana which scholars have not been able to identify. In one or two passages, amounts of gold or silver are mentioned as fines, but in general the Vendidad's punishments are all corporal. This is quite different from other ancient law-books, such as the Jewish laws of Leviticus and Numbers, or the Code of Hammurabi, where punishments are not only corporal but also enumerated in monetary fines or amounts of gold and silver. The punishments of the Vendidad often are so severe that it seems that no one could endure them and live; many offenses incur twice two hundred lashes, and some even merit twice a thousand. Such punishments have caused later readers to wonder whether they were ever actually carried out. The Zoroastrian commentaries on the Vendidad from later centuries, written in Pahlavi or Middle Persian, state that these punishments were commuted to fines, and even give the monetary equivalents of each penalty.

The administrators of both law and punishment were the mobeds, the Zoroastrian priests of the Sassanian empire. They wielded the whip or accepted the fine. This has given rise to the widespread notion that corrupt priests multiplied the numbers of the punishments, seeking to gain more wealth from commuted fines. No doubt some of this is true, and as the Sassanian Empire grew old, the riches and oppression of the state-religion increased. But the Vendidad was also taken seriously, as it still is among traditional Zoroastrians, as a God-given law of holiness which transcends the misdeeds of individual administrators.

It is interesting that during the same time as the Vendidad was being given its final edition, similar work was going on among Christians and Jews. The edition and writing of the Vendidad (though not the actual material contained in it, which may be much older) took place during the era of the great Christian controversies about the nature of Christ and human beings, about God's grace and human sinfulness. The Vendidad may actually be contemporary with Church Fathers such as Augustine of Hippo or John Chrysostom in Constantinople. These were the sages of the Western superpower, the Christian Roman Empire. And the other superpower was the Sassanian Empire of Persia, where its sages were also debating heresies and working out the details of sin and atonement in the Vendidad.

The laws of the Jewish Torah show, in many passages, close resemblance to the laws of the Vendidad, especially in regard to ritual purity. The Jewish texts were re-edited during and after the Exile, when the Jews came into contact with Persia and Zoroastrian ways. It is very possible that Jewish laws either influenced, or were influenced by, the Magian laws of the Vendidad. By the time the Vendidad came to be written down, almost a millennium later, there was still a major Jewish presence in the Persian Empire. The era of the Vendidad's writing is also the era of the compilation of the Babylonian Talmud, a great compendium of Jewish wisdom which is still studied today. The rabbis of the Jewish diaspora in Persia were engaging in similar elaborations and casuistry in their own religious and legal traditions, using as their core text a document which may have already had some Zoroastrian influence from long ago.

How do Zoroastrians view the Vendidad today? And how many of the laws of the Vendidad are still followed? This depends, as so many other Zoroastrian beliefs and practices do, on whether you are a "reformist" or a "traditionalist." The reformists, following the Gathas as their prime guide, judge the Vendidad harshly as being a deviation from the non-prescriptive, abstract teachings of the Gathas. For them, few if any of the laws or practices in the Vendidad are either in the spirit or the letter of the Gathas, and so they are not to be followed. The reformists prefer to regard the Vendidad as a document which has no religious value but is only of historic or anthropological interest. Many Zoroastrians, in Iran, India, and the world diaspora, inspired by reformists, have chosen to dispense with the Vendidad prescriptions entirely or only to follow those which they believe are not against the original spirit of the Gathas.

Traditionalists, however, believe that the Vendidad is indeed divinely inspired, written in the divine language of the Avesta, and that its prescriptions are God's law, the "Law of Mazda." The question then is how to follow ancient laws and practices which were designed for a pre-technological, agrarian society, rather than the modern urban world in which most Zoroastrians live. There are still isolated rural communities of Zoroastrians where many of the Vendidad practices are still done, including daily purity rituals, menstrual seclusion of women, exposure of the dead, and the barashnom for both priests and laypeople. Such a community was documented by Mary Boyce in her book A PERSIAN STRONGHOLD OF ZOROASTRIANISM. But these rural believers are now a minority in the Zoroastrian world. There are Parsis who, though living in the crowded quarters of Bombay, still maintain Vendidad practices; menstrual seclusion takes place in a reserved room in a house or apartment, rather than in a separate building, and Towers of Silence are maintained in the suburbs of the city, where high-rise luxury apartments now crowd a place where originally the Tower stood in wilderness. Many of the practices of necessity have been changed to fit modern circumstances. The most arduous of them are undergone only by priests, such as the barashnom which gives a priest the level of ritual purity necessary to work in a high-grade fire temple. But the system of penalties is gone forever.

Some extremist Zoroastrians view the Vendidad as literally the divine word of God, in which nothing can be changed or modernized. They regard all the laws of the Vendidad as still binding on Zoroastrians. In this view, all Zoroastrians have sinned and come short of their true duties to the law of Mazda, especially those in the West who have no access to Vendidad-prescribed things such as bull's urine, isolation buildings for sickness and menstruation, and Towers of Silence. Zoroastrians, according to the extremists, must live in a constant state of regret because they cannot fulfil the divine laws of the Vendidad. Yet few, if any Zoroastrians, no matter how extreme their views, would like to see a return to a literal re-enactment of the Vendidad, where whip- cracking priests administered four hundred lashes to those who violated the rules of ritual purity.

The Vendidad has a peculiar place in Zoroastrian liturgical practice. Recitation of the complete text is the center of a long ritual which is done as a funerary practice soon after a death, or at other times as a propitiation for sins and exorcism of demons. This ceremony is known simply as a "Vendidad," and is still performed in India and Iran. It takes place at night, when the demons are believed to be at their strongest. The priest recites the whole text, a long task which can take most of the night, reading from his book by the light of flickering lamp-flames. The origin of this practice is obscure, but its meaning is not. The whole Vendidad has now become an extended _manthra_ or formulaic utterance, which is believed to have the power to drive away demonic influences which are particularly dangerous just after a death. The priest is literally laying down the Law for them, for it is the "Anti-Demonic Law."

This practice has had another effect, whether this was intentional or not. Because the Vendidad was used in liturgical practice, it was preserved when other legal texts were lost. The Vendidad is in fact one of the best preserved books of the Avesta. It was this use of the law-book as talismanic utterance which kept it alive through the dark night of history.

7/5/95

Hannah M.G. Shapero

Ushtavaiti

The Ushtavaiti Gatha, which embodies happiness, celebrates the Zoroastrian precept of friendship with God. In Ushtavaiti Gatha, Yasna 46.2 Zarathustra says: “Rafedhrem chagvaao hyat fryo fryaai daidit, Aakhso vangheush ashaa ishtim manangho.” Meaning (as translated by Prof. Stanley Insler): “Take notice of it, Lord, offering the support which a friend should grant to a friend. Let me see the power of good thinking allied with truth!”

Here Zarathushtra does not see God as the Master or the Lord or as Father or someone to fear, but sees Him as a beloved friend to talk to in times of distress and to love Him and seek His support to perfect an imperfect world with friendship based on good thinking allied with Truth.

-- Message Of The Holy Gathas, by Noshir H. Dadrawala