by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/14/21

CHAPTER XV. THE SAME CONTINUED. THE HISTORY OF SAGAMONI BORCAN [SAKYA-MUNI] AND THE BEGINNING OF IDOLATRY.

Furthermore you must know that in the Island of Seilan [Ceylon] there is an exceeding high mountain; it rises right up so steep and precipitous that no one could ascend it, were it not that they have taken and fixed to it several great and massive iron chains, so disposed that by help of these men are able to mount to the top. And I tell you they say that on this mountain is the sepulchre of Adam our first parent; at least that is what the Saracens [Arab Muslims] say. But the Idolaters say that it is the sepulchre of SAGAMONI BORCAN, before whose time there were no idols. They hold him to have been the best of men, a great saint in fact, according to their fashion, and the first in whose name idols were made.[NOTE 1]

He was the son, as their story goes, of a great and wealthy king. And he was of such an holy temper that he would never listen to any worldly talk, nor would he consent to be king. And when the father saw that his son would not be king, nor yet take any part in affairs, he took it sorely to heart. And first he tried to tempt him with great promises, offering to crown him king, and to surrender all authority into his hands. The son, however, would none of his offers; so the father was in great trouble, and all the more that he had no other son but him, to whom he might bequeath the kingdom at his own death. So, after taking thought on the matter, the King caused a great palace to be built, and placed his son therein, and caused him to be waited on there by a number of maidens, the most beautiful that could anywhere be found. And he ordered them to divert themselves with the prince, night and day, and to sing and dance before him, so as to draw his heart towards worldly enjoyments. But 'twas all of no avail, for none of those maidens could ever tempt the king's son to any wantonness, and he only abode the firmer in his chastity, leading a most holy life, after their manner thereof. And I assure you he was so staid a youth that he had never gone out of the palace, and thus he had never seen a dead man, nor any one who was not hale and sound; for the father never allowed any man that was aged or infirm to come into his presence. It came to pass however one day that the young gentleman took a ride, and by the roadside he beheld a dead man. The sight dismayed him greatly, as he never had seen such a sight before. Incontinently he demanded of those who were with him what thing that was? and then they told him it was a dead man. "How, then," quoth the king's son, "do all men die?" "Yea, forsooth," said they. Whereupon the young gentleman said never a word, but rode on right pensively. And after he had ridden a good way he fell in with a very aged man who could no longer walk, and had not a tooth in his head, having lost all because of his great age. And when the king's son beheld this old man he asked what that might mean, and wherefore the man could not walk? Those who were with him replied that it was through old age the man could walk no longer, and had lost all his teeth. And so when the king's son had thus learned about the dead man and about the aged man, he turned back to his palace and said to himself that he would abide no longer in this evil world, but would go in search of Him Who dieth not, and Who had created him.[NOTE 2]

So what did he one night but take his departure from the palace privily, and betake himself to certain lofty and pathless mountains. And there he did abide, leading a life of great hardship and sanctity, and keeping great abstinence, just as if he had been a Christian. Indeed, an he had but been so, he would have been a great saint of Our Lord Jesus Christ, so good and pure was the life he led.[NOTE 3] And when he died they found his body and brought it to his father. And when the father saw dead before him that son whom he loved better than himself, he was near going distraught with sorrow. And he caused an image in the similitude of his son to be wrought in gold and precious stones, and caused all his people to adore it. And they all declared him to be a god; and so they still say. [NOTE 4]

They tell moreover that he hath died fourscore and four times. The first time he died as a man, and came to life again as an ox; and then he died as an ox and came to life again as a horse, and so on until he had died fourscore and four times; and every time he became some kind of animal. But when he died the eighty-fourth time they say he became a god. And they do hold him for the greatest of all their gods. And they tell that the aforesaid image of him was the first idol that the Idolaters ever had; and from that have originated all the other idols. And this befel in the Island of Seilan [Ceylon] in India.

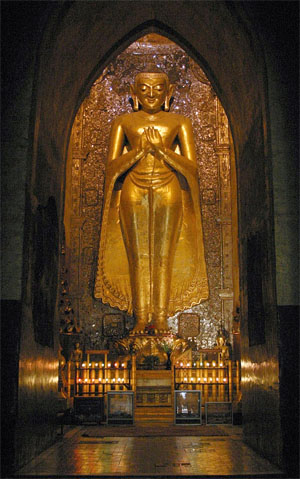

The Idolaters come thither on pilgrimage from very long distances and with great devotion, just as Christians go to the shrine of Messer Saint James in Gallicia. And they maintain that the monument on the mountain is that of the king's son, according to the story I have been telling you; and that the teeth, and the hair, and the dish that are there were those of the same king's son, whose name was Sagamoni Borcan, or Sagamoni the Saint. But the Saracens also come thither on pilgrimage in great numbers, and they say that it is the sepulchre of Adam our first father, and that the teeth, and the hair, and the dish were those of Adam.[NOTE 5]

Whose they were in truth, God knoweth; howbeit, according to the Holy Scripture of our Church, the sepulchre of Adam is not in that part of the world.

Now it befel that the Great Kaan heard how on that mountain there was the sepulchre of our first father Adam, and that some of his hair and of his teeth, and the dish from which he used to eat, were still preserved there. So he thought he would get hold of them somehow or another, and despatched a great embassy for the purpose, in the year of Christ, 1284. The ambassadors, with a great company, travelled on by sea and by land until they arrived at the island of Seilan [Ceylon], and presented themselves before the king. And they were so urgent with him that they succeeded in getting two of the grinder teeth, which were passing great and thick; and they also got some of the hair, and the dish from which that personage used to eat, which is of a very beautiful green porphyry. And when the Great Kaan's ambassadors had attained the object for which they had come they were greatly rejoiced, and returned to their lord. And when they drew near to the great city of Cambaluc, where the Great Kaan was staying, they sent him word that they had brought back that for which he had sent them. On learning this the Great Kaan was passing glad, and ordered all the ecclesiastics and others to go forth to meet these reliques, which he was led to believe were those of Adam.

And why should I make a long story of it? In sooth, the whole population of Cambaluc went forth to meet those reliques, and the ecclesiastics took them over and carried them to the Great Kaan, who received them with great joy and reverence.[NOTE 6] And they find it written in their Scriptures that the virtue of that dish is such that if food for one man be put therein it shall become enough for five men: and the Great Kaan averred that he had proved the thing and found that it was really true.[NOTE 7]

So now you have heard how the Great Kaan came by those reliques; and a mighty great treasure it did cost him! The reliques being, according to the Idolaters, those of that king's son.

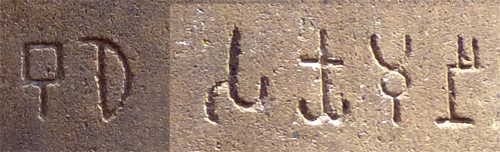

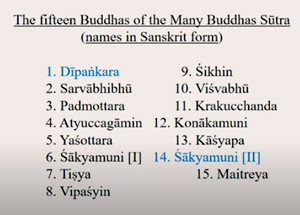

NOTE 1.—Sagamoni Borcan is, as [William] Marsden points out, SAKYA-MUNI, or Gautama-Buddha, with the affix BURKHAN, or "Divinity," which is used by the Mongols as the synonym of Buddha.

NOTE 2.—The general correctness with which Marco has here related the legendary history of Sakya's devotion to an ascetic life, as the preliminary to his becoming the Buddha or Divinely Perfect Being, shows what a strong impression the tale had made upon him. He is, of course, wrong in placing the scene of the history in Ceylon, though probably it was so told him, as the vulgar in all Buddhist countries do seem to localise the legends in regions known to them.

Sakya Sinha, Sakya Muni, or Gautama, originally called Siddhárta, was the son of Súddhodhana, the Kshatriya prince of Kapilavastu, a small state north of the Ganges, near the borders of Oudh. His high destiny had been foretold, as well as the objects that would move him to adopt the ascetic life. To keep these from his knowledge, his father caused three palaces to be built, within the limits of which the prince should pass the three seasons of the year, whilst guards were posted to bar the approach of the dreaded objects. But these precautions were defeated by inevitable destiny and the power of the Devas.

When the prince was sixteen he was married to the beautiful Yasodhara, daughter of the King of Koli, and 40,000 other princesses also became the inmates of his harem.

"Whilst living in the midst of the full enjoyment of every kind of pleasure, Siddhárta one day commanded his principal charioteer to prepare his festive chariot; and in obedience to his commands four lily-white horses were yoked. The prince leaped into the chariot, and proceeded towards a garden at a little distance from the palace, attended by a great retinue. On his way he saw a decrepit old man, with broken teeth, grey locks, and a form bending towards the ground, his trembling steps supported by a staff (a Deva had taken this form)…. The prince enquired what strange figure it was that he saw; and he was informed that it was an old man. He then asked if the man was born so, and the charioteer answered that he was not, as he was once young like themselves. 'Are there,' said the prince, 'many such beings in the world?' 'Your highness,' said the charioteer, 'there are many.' The prince again enquired, 'Shall I become thus old and decrepit?' and he was told that it was a state at which all beings must arrive."

The prince returns home and informs his father of his intention to become an ascetic, seeing how undesirable is life tending to such decay. His father conjures him to put away such thoughts, and to enjoy himself with his princesses, and he strengthens the guards about the palaces. Four months later like circumstances recur, and the prince sees a leper, and after the same interval a dead body in corruption. Lastly, he sees a religious recluse, radiant with peace and tranquillity, and resolves to delay no longer. He leaves his palace at night, after a look at his wife Yasodhara and the boy just born to him, and betakes himself to the forests of Magadha, where he passes seven years in extreme asceticism. At the end of that time he attains the Buddhahood. (See Hardy's Manual p. 151 seqq.) The latter part of the story told by Marco, about the body of the prince being brought to his father, etc., is erroneous. Sakya was 80 years of age when he died under the sál trees in Kusinára...

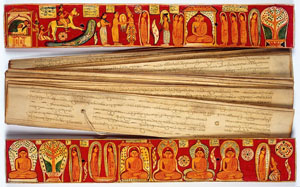

NOTE 6.—The Pâtra, or alms-pot, was the most valued legacy of Buddha. It had served the three previous Buddhas of this world-period, and was destined to serve the future one, Maitreya. The Great Asoka sent it to Ceylon. Thence it was carried off by a Tamul chief in the 1st century, A.D., but brought back we know not how, and is still shown in the Malagawa Vihara at Kandy. As usual in such cases, there were rival reliques, for Fa-hian found the alms-pot preserved at Pesháwar. Hiuen Tsang says in his time it was no longer there, but in Persia. And indeed the Pâtra from Pesháwar, according to a remarkable note by Sir Henry Rawlinson, is still preserved at Kandahár, under the name of Kashkul (or the Begging-pot), and retains among the Mussulman Dervishes the sanctity and miraculous repute which it bore among the Buddhist Bhikshus. Sir Henry conjectures that the deportation of this vessel, the palladium of the true Gandhára (Pesháwar), was accompanied by a popular emigration, and thus accounts for the transfer of that name also to the chief city of Arachosia. (Koeppen, I. 526; Fah-hian, p. 36; H. Tsang, II. 106; J.R.A.S. XI. 127.)

Sir E. Tennent, through Mr. Wylie (to whom this book owes so much), obtained the following curious Chinese extract referring to Ceylon (written 1350): "In front of the image of Buddha there is a sacred bowl, which is neither made of jade nor copper, nor iron; it is of a purple colour, and glossy, and when struck it sounds like glass. At the commencement of the Yuen Dynasty (i.e. under Kúblái) three separate envoys were sent to obtain it." Sanang Setzen also corroborates Marco's statement: "Thus did the Khaghan (Kúblái) cause the sun of religion to rise over the dark land of the Mongols; he also procured from India images and reliques of Buddha; among others the Pâtra of Buddha, which was presented to him by the four kings (of the cardinal points), and also the chandana chu" (a miraculous sandal-wood image). (Tennent, I. 622; Schmidt, p. 119.)

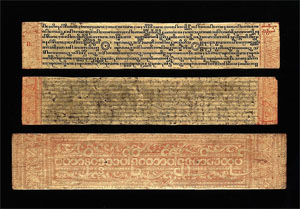

The text also says that several teeth of Buddha were preserved in Ceylon, and that the Kaan's embassy obtained two molars. Doubtless the envoys were imposed on; no solitary case in the amazing history of that relique, for the Dalada, or tooth relique, seems in all historic times to have been unique. This, "the left canine tooth" of the Buddha, is related to have been preserved for 800 years at Dantapura ("Odontopolis"), in Kalinga, generally supposed to be the modern Púri or Jagannáth. Here the Brahmans once captured it and carried it off to Palibothra, where they tried in vain to destroy it. Its miraculous resistance converted the king, who sent it back to Kalinga. About A.D. 311 the daughter of King Guhasiva fled with it to Ceylon. In the beginning of the 14th century it was captured by the Tamuls and carried to the Pandya country on the continent, but recovered some years later by King Parakrama III., who went in person to treat for it. In 1560 the Portuguese got possession of it and took it to Goa. The King of Pegu, who then reigned, probably the most powerful and wealthy monarch who has ever ruled in Further India, made unlimited offers in exchange for the tooth; but the archbishop prevented the viceroy from yielding to these temptations, and it was solemnly pounded to atoms by the prelate, then cast into a charcoal fire, and finally its ashes thrown into the river of Goa.

The King of Pegu was, however, informed by a crafty minister of the King of Ceylon that only a sham tooth had been destroyed by the Portuguese, and that the real relique was still safe. This he obtained by extraordinary presents, and the account of its reception at Pegu, as quoted by Tennent from De Couto, is a curious parallel to Marco's narrative of the Great Kaan's reception of the Ceylon reliques at Cambaluc. The extraordinary object still so solemnly preserved at Kandy is another forgery, set up about the same time. So the immediate result of the viceroy's virtue was that two reliques were worshipped instead of one!

The possession of the tooth has always been a great object of desire to Buddhist sovereigns. In the 11th century King Anarauhta, of Burmah, sent a mission to Ceylon to endeavour to procure it, but he could obtain only a "miraculous emanation" of the relique. A tower to contain the sacred tooth was (1855), however, one of the buildings in the palace court of Amarapura. A few years ago the King of Burma repeated the mission of his remote predecessor, but obtained only a model, and this has been deposited within the walls of the palace at Mandalé, the new capital. (Turnour in J.A.S.B. VI. 856 seqq.; Koeppen, I. 521; Tennent, I. 388, II. 198 seqq.; MS. Note by Sir A. Phayre; Mission to Ava, 136.)

Of the four eye-teeth of Sakya, one, it is related, passed to the heaven of Indra; the second to the capital of Gandhára; the third to Kalinga; the fourth to the snake-gods. The Gandhára tooth was perhaps, like the alms-bowl, carried off by a Sassanid invasion, and may be identical with that tooth of Fo, which the Chinese annals state to have been brought to China in A.D. 530 by a Persian embassy. A tooth of Buddha is now shown in a monastery at Fu-chau; but whether this be either the Sassanian present, or that got from Ceylon by Kúblái, is unknown. Other teeth of Buddha were shown in Hiuen Tsang's time at Balkh, at Nagarahára (or Jalálábád), in Kashmir, and at Kanauj. (Koeppen, u.s.; Fortune, II. 108; H. Tsang, II. 31, 80, 263.)

[Illustration: Teeth of Budda. 1. At Kandy, after Tennent. 2. At Fu-Chau from Fortune.]

NOTE 7.—Fa-hian writes of the alms-pot at Pesháwar, that poor people could fill it with a few flowers, whilst a rich man should not be able to do so with 100, nay, with 1000 or 10,000 bushels of rice; a parable doubtless originally carrying a lesson, like Our Lord's remark on the widow's mite, but which hardened eventually into some foolish story like that in the text.

The modern Mussulman story at Kandahar is that the alms-pot will contain any quantity of liquor without overflowing.

This Pâtra is the Holy Grail of Buddhism. Mystical powers of nourishment are ascribed also to the Grail in the European legends. German scholars have traced in the romances of the Grail remarkable indications of Oriental origin. It is not impossible that the alms-pot of Buddha was the prime source of them. Read the prophetic history of the Pâtra as Fa-hian heard it in India (p. 161); its mysterious wanderings over Asia till it is taken up into the heaven Tushita where Maitreya the Future Buddha dwells. When it has disappeared from earth the Law gradually perishes, and violence and wickedness more and more prevail:...—"What is it?

The phantom of a cup that comes and goes?

* * * * * If a man

Could touch or see it, he was heal'd at once,

By faith, of all his ills. But then the times

Grew to such evil that the holy cup

Was caught away to Heaven, and disappear'd."

—Tennyson's Holy Grail

In a paper on Burkhan printed in the Journal of the American Oriental Society, XXXVI., 1917, pp. 390-395, Dr. Berthold Laufer has come to the following conclusion: "Burkhan in Mongol by no means conveys exclusively the limited notion of Buddha, but, first of all, signifies 'deity, god, gods,' and secondly 'representation or image of a god.' This general significance neither inheres in the term Buddha nor in Chinese Fo; neither do the latter signify 'image of Buddha'; only Mongol burkhan has this force, because originally it conveyed the meaning of a shamanistic image. From what has been observed on the use of the word burkhan in the shamanistic or pre-Buddhistic religions of the Tungusians, Mongols and Turks, it is manifest that the word well existed there before the arrival of Buddhism, fixed in its form and meaning, and was but subsequently transferred to the name of Buddha."

-- The Travels of Marco Polo, by Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa

Henri Cordier

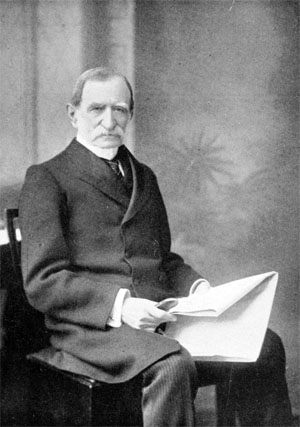

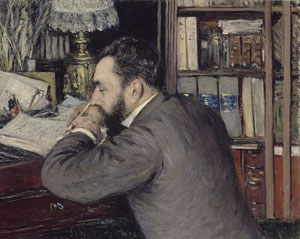

Portrait of Henri Cordier at work, by Gustave Caillebotte (1883)

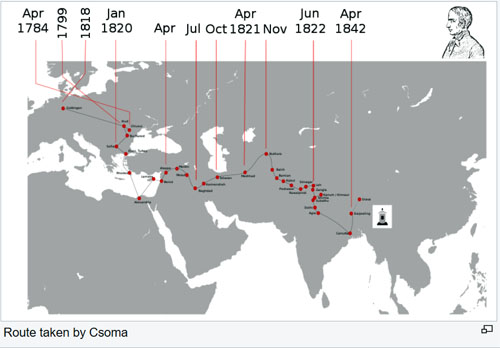

Born: 8 August 1849, New Orleans, Louisiana, United States

Died: 16 March 1925 (aged 75), Paris, France

Known for East Asian studies

Henri Cordier (8 August 1849 – 16 March 1925) was a French linguist, historian, ethnographer, author, editor and Orientalist. He was President of the Société de Géographie (French, "Geographical Society") in Paris.[1] Cordier was a prominent figure in the development of East Asian and Central Asian scholarship in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century. Though he had little actual knowledge of the Chinese language, Cordier had a particularly strong impact on the development of Chinese scholarship, and was a mentor of the noted French sinologist Édouard Chavannes.

Early life

Cordier was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in the United States. He arrived in France in 1852; and his family moved to Paris in 1855. He was educated at the Collège Chaptal and in England.[2]

In 1869 at age 20, he sailed for Shanghai, where he worked at an English bank. During the next two years, he published several articles in local newspapers. In 1872, he was made librarian of the North China branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. In this period, about twenty articles were published in Shanghai Evening Courier, North China Daily News, and Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.[2]

Career

In 1876, he was named secretary of a Chinese government program for Chinese students studying in Europe.[2]

In Paris, Cordier was a professor at l'École spéciale des Langues orientales, which is known today as the Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (L’Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales, INALCO).[3] He joined the faculty in 1881; and he was a professor from 1881-1925.[2] He contributed a number of articles to the Catholic Encyclopedia.[4]

Cordier was also a professeur at l'École Libre des Sciences Politiques, which is today known as the National Foundation of Political Studies (Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques) and the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris).[3]

Contributions to Sinology

Although he had only a slight knowledge of the language, Cordier made major contributions to Sinology.

"Cordier," as the Bibliotheca Sinica "is sometimes affectionately referred to," is "the standard enumerative bibliography" of 70,000 works on China up to 1921. Even though the author did not know Chinese, he was thorough and highly familiar with European publications. Endymion Wilkinson also praises Cordier for including the full titles, often the tables of contents, and reviews of most books.[5]

Cordier was a founding editor of T'oung Pao, which was the first international journal of Chinese Studies. Along with Gustaaf Schlegel, he helped to establish the prominent sinological journal T'oung Pao in 1890.[3]

Honors

• Royal Asiatic Society, honorary member, 1893.[2]

• Royal Geographical Society, corresponding member, 1908.[2]

• Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, member, 1908.[2]

• Société Asiatique, vice-president, 1918-1925.[2]

• Société de Géographie, President, 1924-1925.[1]

Selected works

Cordier's published writings encompass 1,033 works in 1,810 publications in 13 languages and 7,984 library holdings.[6]

• Bibliotheca sinica. Dictionnaire bibliographique des ouvrages relatifs à l'Empire chinois, Vol. 1; Vol. 2. (1878-1895)

• Bibliographie des œuvres de Beaumarchais (1883)

• La France en Chine au XVIIIe siècle: documents inédits/publiés sur les manuscrits conservés au dépôt des affaires étrangères, avec une introduction et des notes (1883)

• Mémoire sur la Chine adressé à Napoléon Ier: mélanges, Vol. 1; Vol. 2; by F. Renouard de Ste-Croix, edited by Henri Cordier. (1895-1905)

• Les Origines de deux établissements français dans l'Extrême-Orient: Chang-Haï, Ning-Po, documents inédits, publiés, avec une introduction et des notes (1896)

• La Révolution en Chine: les origines (1900)

• Conférence sur les relations de la Chine avec l'Europe. (1901)

• L'Imprimerie sino-européenne en Chine: bibliographie des ouvrages publiés en Chine par les Européens au XVIIe et au XVIIIe siècle. (1901)

• Dictionnaire bibliographique des ouvrages relatifs à l'Empire chinois: bibliotheca sinica, Vol. 1; Vol. 2; Vol. 3; Vol. 4. (1904-1907)

• The Book of Ser Marco Polo : vol.1 The Book of Ser Marco Polo : vol.2 with Henry Yule (1903)

• Ser Marco Polo : vol.1 (1910)

• L'Expédition de Chine de 1860, histoire diplomatique, notes et documents (1906)

• Bibliotheca Indosinica. Dictionnaire bibliographique des ouvrages relatifs à la péninsule indochinoise (1912)

• Bibliotheca Japonica. Dictionnaire bibliographique des ouvrages relatifs à l'empire Japonais rangés par ordre chronologique jusqu'à 1870 (1912)

• Mémoires Concernant l'Asie Orientale : vol.1 Mémoires Concernant l'Asie Orientale : vol.2 Mémoires Concernant l'Asie Orientale : vol.3 (1913)

• Le Voyage à la Chine au XVIIIe siècle. Extrait du journal de M. Bouvet, commandant le vaisseau de la Compagnie des Indes le Villevault (1765-1766) (1913)

• Cathay and the Way Thither: being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China (1913)

• Bibliographie stendhalienne (1914)

• La Suppression de la compagnie de Jésus et la mission de Péking (1918)

• The travels of Marco Polo (1920), with Henry Yule

• Histoire générale de la Chine et de ses relations avec les pays étrangers: depuis les temps les plus anciens jusqu'à la chute de la dynastie Mandchoue, Vol. I, Depuis les temps les plus anciens jusqu'à la chute de la dynastie T'ang (907); Vol. 2, Depuis les cinq dynasties (907) jusqu'à la chute des Mongols (1368); Vol. 3, Depuis l'avènement des Mings (1368) jusqu'à la mort de Kia K'ing (1820); Vol. 4, Depuis l'avènement de Tao Kouang (1821) jusqu'à l'époque actuelle. (1920-1921)

• La Chine. (1921)

• La Chine en France au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1910)

• Chine : vol.1

Notes

1. La Société de Géographie Archived 2007-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, List of Presidents Archived 2010-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

2. Aurousseau, L. (1925). Nécrologie, Henri Cordier," Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, Vol. 25, Issue 25, pp. 279-286.

3. T'oung Pao, Vol. I, first issue cover page, 1890.

4. "Cordier, Henri", The Catholic Encyclopedia and Its Makers, New York, the Encyclopedia Press, 1917, p. 34 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

5. Endymion Wilkinson. Chinese History: A New Manual. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, 2013 ISBN 9780674067158) p. 986

6. WorldCat Identities Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine: Cordier, Henri 1849-1925

References

• Cordier, Henri. (1892). Half a Decade of Chinese studies (1886-1891). Leyden: E.J. Brill. OCLC 2174926

• Pelliot, Paul (1925). "Henri Cordier (1849-1925)". T'oung Pao (in French). 24 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1163/156853226X00011. JSTOR 4526773.

• Ross, E. Denison (1925). "M. Henri Cordier". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (3): 571–2. JSTOR 25220805.

• Yetts, W. Perceval (1925). "Obituary – Professor Henri Cordier". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 3 (4): 855–6. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00000781. JSTOR 607118.

• Ting Chang, “Crowdsourcing avant la lettre: Henri Cordier and French Sinology, ca. 1875–1925”, L'Esprit créateur, Volume 56, Number 3, Fall 2016, Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 47-60.

External links

• T’oung Pao Brill's official website

• Works by Henri Cordier at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Henri Cordier at Internet Archive

• Downloadable issues of T'oung pao