by Elena Bonollo

From Defining Authorship, Debating Authenticity: Problems of Authority from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

Edited by Roberta Berardi, Martina Filosa, and Davide Massimo

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

1 An Authorial Perspective on the Corpora: Their Ascription to the Authority of Menander and the Contribution of 'Co-Authors'

The so-called [x] (or Menandri Sententiae)1 prove to be a very particular and apparently quite inconsistent case as far as the issues of authority and authenticity are concerned. In fact, the high value originally attributed to the figure of a precise author, Menander, to whom the whole corpus of these gnomic lines was attributed, contrasts sharply with the legitimation felt by ancient scholars and copyists to alter this corpus of maxims since the early stages of its transmission. In the following pages, I will hopefully clarify the cultural context of these operations and present some results of my comparative study between the monostichs gathered under the title of Menandri Sententiae and Menander's original lines. On these bases, I will attempt to classify the modalities of variation the [x] display and to understand the possible reasons behind them.

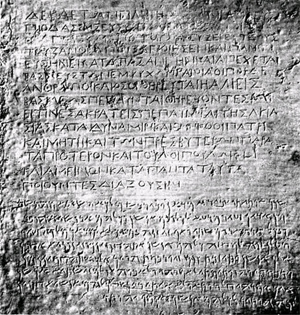

Certainly one of the most well-known and commonly used literary forms until the Byzantine age, the [x] have come to us in several different testimonies, papyri, ostraka, and manuscripts, including three redactions (one prepared by Maximus Planudes, another by Georgius Hermonimus, and a third one attributed to Gregory of Nazianzus) and translations in Coptic, Arabic, and paleo-Slavic.2 Before (and after) being gathered in collections, maxims were inserted in a range of genres, both poetry and prose, among which Menander's comedy was no exception. In order to explain briefly what is meant by sententiae (or [x]) and how Menander nestled them in his plays, a comparison to proverbs ([x]) might be of help.3 In fact, maxim and proverb share the same didactic, asserting tone in stating a fact, in recommending -- or warning against -- a certain behaviour, and both refer to that praised system of values operating in Menandrean plosts, in which the audience could recognize themselves. The differentiating element is the originality of the formulation: the proverb has an established fixed form which makes it an anonymous, universally acknowledged truth or a precept of popular wisdom, in quoting which our playwright is just one among many other authors.4 On the other hand, the sententia is a reflection newly shaped by the author and is connected with the textual context and dramatic situation in which he framed it. In some cases, the sententia has been later proverbialized.5

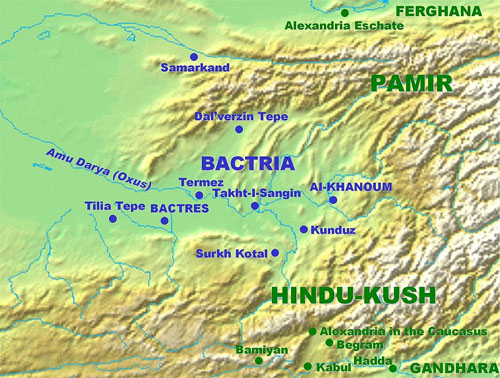

Considering then the numerous corpora in which the Menandri Sententiae were assembled and transmitted through 15 centuries, the question of the origin of such collections was raised. The previously established theory by W. Meyer and A. Korte postulated a proto-collection (Ur-Sammlung), thematically ordered and including iambic trimeters from various explicitly named authors. This compilation gradually dissolved -- according to this theory -- into the many incomplete redactions we find in our sources, which have also been continuously deteriorated by the progressive inclusion of new, inferior material.6 Such a hypothetical reconstruction has become a matter of hesitation and debate among later scholars,7 and if an original nucleus of Menandrean lines may well be assumed, it must be acknowledged that additions, contaminations, and the fluid circulation of parallel groups of maxims began very early. Equally early in the history of such collections of gnomic materials, the corpora of [x] started being transmitted under the name of the one poet whose accessible language, ethopoietic skills, and moral principles were generally appreciated and popular in Antiquity: Menander. The two constant features with which these collections of maxims known by his name have developed in the following centuries are the alphabetical order according to which the sententiae are disposed and the limits of one verse into which the thought needs to be expressed.

Menander, however, must be recognized as the authority rather than the author of the entire collections of [x] attributed to his hand. Only a tiny section of the currently edited 1029 [x] is held to have been truly quoted from his plays, while the inclusion and/or re-elaboration of the remaining ones, as well as the arrangement of this gnomological work, has to be ascribed to a number of different figures who may well be entitled to be called 'co-authors'.8 In fact, over the long period of time from the 1st century AD, to which the first papyri we have are dated, to the 16th century, the collections and the texts therein underwent all sorts of alterations: extensions by means of additions of new gnomic materials, omissions, and re-formulations.9

The reason for this intrinsic fluidity of the [x] tradition is to be found in ancient school practices, since pupils used to train on maxims at all stages of their education: they started by learning to write and read with the texts of morally edifying sententiae at the lessons of the [x], and then honed their rhetorical skills by adapting or paraphrasing the same maxims in advanced [x].10 Commonly manipulated in schools, the gnomai were liable to re-elaborations by both sides of a school classroom: teachers (who often were excerptores, i.e. 'compilers', of their own copies of the Menandri Sententiae) and their pupils, [x] are therefore a good example of Gebrauchsliteratur, being copied with a practical rather than conservative aim.11 In their treatises, entitled Progymnasmata ('exercises'), Hermogenes and Theon -- just to mention two among many others -- explain and praise these practices, documented by the many papyri and manuscripts circulating in Greek-speaking schools up to the end of the Byzantine period.12 Identical learning methods were adopted in Latin schools, as Quintilian and Seneca the Elder attest.13

GnomaiLife is not a highway strewn with flowers. -- English popular song

In English, the term ‘gnomic saying’ has a wide scope, including proverbs, riddles, mottoes, legal axioms and even the epimythia of fables.1 Gnome in Greek and sententia in Latin are used of both proverbs and moralizing quotations, but for clarity, I am restricting them to the second group.2 The boundary, as we have seen, is occasionally hazy, as poets give memorable form to common sentiments or attributable quotations become proverbial. As usual, when in doubt I follow the sources’ own view of whether a particular saying is popular and anonymous (i.e. proverbial) or has a known origin. The most famous example of a borderline case in this chapter is the Sayings of the Seven Sages. These, which should probably, properly, be regarded as anonymous and proverbial, overlap both with the Delphic maxims and with some proverbs, but they were so generally attributed to the Sages in antiquity that it seems perverse not to count them as gnomai.3

Despite overlapping vocabulary and some borderline cases, Greek and Latin speakers could and did distinguish between quotations and anonymous proverbs, and the overlap of identical material between anthologies of proverbs and gnomic sayings is tiny (a fraction of a percentage point).4 The definition of a gnome was of particular interest to rhetoricians. Hermogenes of Tarsus offers this in his second-century Progymnasmata:1Gnome is a summary statement, in universal terms, dissuading or exhorting in regard to something, or making clear what a particular thing is. Dissuading, as in the following (Il. 2.24): ‘A man who is a counsellor should not sleep throughout the night’; exhorting, as in the following (Theognis 175): ‘One fleeing poverty, Cyrnis, must throw himself/Into the yawning sea and down steep crags.’ Or it does neither of these things but explains the nature of something; for example (Demosthenes 1.23): ‘Undeserved success is for the unintelligent the beginning of thinking badly.’5

Theon, writing his Progymnasmata a century earlier, does not give gnomai a section to themselves, but treats them alongside chreiai, distinguishing the two as follows:A chreia is a brief saying or action indicating shrewdness, attributed to some specified person or analogy of a person, and gnome and apomnemoneuma (reminiscence) are connected with it. Every brief gnome attributed to a person creates a chreia. A reminiscence is an action or a saying useful for life. The gnome, however, differs from the chreia in four ways; the chreia is always attributed to a person, the gnome not always; the chreia sometimes states a universal, sometimes a particular, the gnome only a universal; furthermore, sometimes the chreia is a pleasantry not useful for life, the gnome is always about something; fourth, the chreia is an action or a saying, the gnome only a saying.6

Function is as important as form for these authors when discussing the gnome (and for that matter the chreia, reminiscence and fable), and the function of a gnome is explicitly ethical: it is useful; it tells you something about the nature of the world, or about what to do or not to do. This view is expressed as a commonplace in other authors. Dio Chrysostom, speaking on how to prepare oneself for public speaking, urges his listeners to read Euripides and Menander; among the virtues of Euripides is that he scatters his plays with gnomai which are useful for all occasions.7 For Plutarch, no-one is more instructive than Menander, while Quintilian, whose analysis of the sententia runs to thirty-five paragraphs, a formidable range of sub-types and an exhaustive discussion of when it is and is not appropriate to use them, calls sententiae lumina, lights which illuminate the nature of things or persons.8 Gnomai or sententiae are meant to be taken seriously, heard, read, marked, learned and inwardly digested, and then put to use.9

From the first and second centuries, well over a thousand gnomic sayings survive in anthologies, in manuscript or on papyrus, while hundreds more are embedded in almost every kind of literature. From Menander, the single most popular source of gnomai in either language, no fewer than 866 lines in Greek (to say nothing of Latin versions) have been collected, many of which are attested several times; many of these are collected in anthologies but most are embedded in other works of literature.10 Such embedded gnomai are often produced with something of a fanfare, complete with their source. So, for instance, Seneca the Younger, discoursing on anger, says, ‘What of the fact that fear always rebounds on its authors and that no-one who is feared is safe himself? That line of Laberius may occur to you at this point, the one which (spoken in the theatre in the middle of a civil war) captured the whole populace as if the voice of public feeling itself had spoken: “The one whom many fear must fear many.”’11 On other occasions, a gnome is introduced but the audience is left to supply the author. So Paul of Tarsus, in The Acts of the Apostles, woos the Athenians with their shared knowledge of Aratus: ‘From one man, [God] made every race of men to inhabit the whole face of the earth, and he set out when and where they would live, so that they would seek God and perhaps grope for him and find him -– though he is not far from any of us. For “in him we live and move and exist”; as some of your poets have said, “for we are also his offspring”.’12 Paul, in his own writings, is capable of an even subtler use of the gnome, as when he slips a fragment of Menander’s Thaıs into his advice to the Christians of Corinth, ‘Do not stray: “Bad company destroys good morals.”’13

Most quotations in literary works are not moralistic, and of those that are, most are grammatically incomplete -– a few words or a clause from a well-known passage -– or they are simply alluded to or invoked in passing, with an image or a familiar turn of phrase. These I have excluded from the analysis, on the grounds (parallel to those on which I excluded some proverbial phrases from Chapter Two) that a gnome proper is a grammatically complete sentence as well as a complete thought. Quotations of more than two lines (which are much rarer) I have included if they express a single, coherent moralizing idea, like the paradigmatic monostichs and distichs.9 This five-line quotation from Euripides in Aulus Gellius’ Attic Nights, for instance, qualifies: ‘What more do mortals need than these two things, the fruits of Demeter and the cool water of the spring, which are to hand and exist to feed us? All this does not satisfy us, but we hunt for other ways of eating in luxury.’14

Within anthologies, gnomai are easier to identify but often harder to date. Two important Latin collections, which have survived in manuscript and have some claim to have existed in the first or second century, are a case in point. The Dicta Catonis form a collection of sayings, some very brief and apparently modelled on the Sayings of the Seven Sages, some monostichs or distichs in hexameter verse, which was widely copied in late antiquity under the name of Cato the Elder. Some of these sayings were known in the first and second centuries,15 and a collection was in existence by the fourth. How far back we can trace them is harder to tell. Cato, consul and censor in the second century and a byword for moral probity since at least the first century BCE, was an obvious figure to whom to attach gnomai. (Plutarch, in his Life, attributes many more to him, some of which are translations of Menander monostichs; Seneca too quotes a ‘saying of Cato’ which does not appear in the distichs.16 ) There is no indication, however, that he wrote verse on a scale to produce this many gnomic quotations (though he left a number of prose works). There is, moreover, a suspicious absence of quotations from the Dicta in authors of the first and second centuries. Worse still, whatever the collection’s original form, it is clear that the versions which have come down to us are heavily Christianized. For all these reasons, I doubt we can convincingly identify any part of the Dicta Catonis as a collection in circulation in the first and second centuries, so I have not included it here.17

We are on firmer ground with the collection of Publilius Syrus. Publilius came to Rome in the mid-first century BCE as a slave.18 At some point he was freed and made his reputation writing Latin mimes which, like Greek and Latin comedy, periodically made use of a highly gnomic style. There is good evidence that he was known, quoted and admired in the first and second centuries CE. Seneca the Elder comments on his gift for apt expression; Petronius imitates him, and Gellius quotes a number of his sententiae.19 In the fourth century, Jerome learned his maxims.20 Like the Dicta Catonis, Publilius’ sayings were adapted for Christian audiences, prose material was added and the collection circulated in the Middle Ages in diverse forms. Over 700 sententiae, however, have been identified as original, and it seems plausible that they were in circulation in the first and second centuries CE.21

Gnomic anthologies in Greek present slightly different problems. Here we do have a large number of fragmentary texts, on papyrus, clearly written under the early Roman Empire, some in professional literary hands, while others are scholarly compilations or school texts. In this case, however, I have allowed myself to stray beyond my usual chronological bounds and include material which may date to as late as the fourth century. This is partly because it is not always easy to date papyri to one century, especially in literary hands, and many of the texts I shall be using are dated to, for instance, the second or third century, occasionally even the second, third or fourth. It is also partly because the accidents of survival and excavation mean that notoriously few papyri of any kind survive from the first century CE, and many of the best-preserved gnomic anthologies are possibly or certainly later than the second. Many date from even later than the fourth, and a few from earlier, but one can defend the inclusion of material from the first to the fourth centuries in a way in which one might not want to defend earlier or later material.

If we consider the whole range of literature surviving on papyrus during the Graeco-Roman period, we notice that across Egypt, a much wider range of literature seems to have been read under the Ptolemies than under the Romans. By the second century CE (outside one or two pockets of intense scholarly activity), a relatively narrow range of authors and texts survive in any numbers.22 Reading habits then seem to have been relatively stable until the fourth century, when the number and range of Greek and Latin secular literature begin to fall again (while Christian, especially biblical, material rises sharply). To include gnomic anthologies from the Ptolemaic period, therefore, in this analysis would be to include material which might well have gone out of circulation by the early Empire. To include collections from later than the fourth century would be to give too much statistical weight to their contents and potentially to distort the earlier picture. (One sixth- or seventh-century anthology, for instance, includes many gnomai about death (reflecting perhaps a Christian influence), which makes it rather different from earlier collections.23 To include it in the analysis would make death look a much more important topic in the early Empire than other collections suggest.) We can fortify first- and second-century material with texts from the third and fourth centuries, however, without serious danger of distorting the picture they create.

From the first to the fourth centuries, some ninety-five more or less readable texts of gnomic anthologies survive, together with a handful too fragmentary to yield more than odd words. Between them, they contain around 300 decipherable gnomic sayings. Most are not attributed in the papyri as we have them (though we rarely have the beginning or end of a text, where attributions most often occur). Around half, however, can be firmly attributed to an author and usually a work. The largest number come from Menander (or other new comic poets, whose gnomai tended to be dubbed ‘Menandrean’). The most popular prose works are ps.-Isocrates’ Ad Demonicum, Ad Nicoclem or Nicocles. Five texts can be firmly attributed to Euripides. Three survive from Plutarch’s Sympotic Problems and one each from (or attributed to) Hesiod, Philemon, Hermarchus, Moschion, Antiphon, Potamon, Aristotle, Aristippus, Diphilus, Pythagoras, Favorinus, Antisthenes, Chares, Chaeremon and Diogenes the Cynic – as eclectic a range of authors as was read anywhere in Egypt at the time. Between them, they are widely distributed across the province, showing that gnomic material was, geographically at least, more widely spread than any literature other than Homer in the Roman period.

It is common now -– when fragments of gnomologies survive only on papyrus, in the monumental, but more admired than studied compilation of Stobaeus, in the little-read late-antique manuscripts collected by Boissonade,24 in what are classified as minor Latin poets or in Arabic and modern European translations -– to underestimate their importance in the Hellenistic and especially the Roman world. To judge by the number of surviving papyrus fragments, however, the number of mediaeval manuscripts of some collections and the frequency with which certain gnomai were quoted by other authors, gnomai and gnomic collections were among the most widely familiar literary material in the Roman world – quite likely, after Homer (and possibly, in the west, Virgil), the most familiar material.25 Gnomai were among the first texts people read and copied when learning to read and write, so everyone with even the most basic level of literacy read some. Professional scribes made fair copies of them for wealthy patrons, and scholars copied them in informal hands. Where they were read, no doubt they were also quoted and so spread through parts, at least, of the non-literate population.26 Gnomai were familiar to anyone who read or had contact with someone who read. They helped to form the mindset of Greek and Latin speakers across the Empire, oiled the wheels of their thinking and coloured and vitalized their speech.

-- Chapter 4: Gnomai, from "Popular Morality in the Early Roman Empire," by Teresa Morgan

The process of alteration was continued by Mediaeval copyists. Having lost any connection with Menander, an author they did not know anything about, they could easily draw materials from various sources as well as from their own memory (following the mental associations the maxims suggested to them) and readjust them to fit into their collections of one-line sententiae. Similar operations of aggregation and adaptation resulting in collections of maxims might have characterized the ancient, pre-Mediaeval phase of the Menandri Sententiae tradition as well. In fact, the use of [x] in schools coexisted, as papyri attest,14 with their inclusion in proper books and, although this kind of compilations aimed at the conservation and the transmission of the Sententiae, it does not necessarily follow that the maxims could escape their inherent instability.15

The procedure of progressive additions of new material in particular requires specific explanations. In fact, a hypothetical original nucleus of Menander's authentic gnomai was extended with lines coming from two different directions. The first might be generically indicated as Greek poetry and includes other Menandrean quotations, as well as extracts from other authors, especially playwrights and, above all, Euripides, whose lines in the Menandri Sententiae are almost as numerous as Menander's. Materials from these authors could be either drawn directly from their texts or gleaned from other gnomological anthologies. On the other hand, as the aforementioned Greek and Latin testimonies attest, behind some additions there is the creative paraphrase by teachers and students themselves, who contributed to accumulate those similar lines, slightly varied in words and word order, that Meyer called Parallelverse.16 For example, Planudes' redaction of the Menandri Sententiae and the Arabic and paleo-Slavic translations of this corpus show that Menander's fr. 829 was included in the collection holding the same text which Stobaeus17 also quoted: [x] (sent. 314).18 Codex B (Par. gr. 396) of the Sententiae, however, presents a similar but not identical text, resulting in a variation on the same theme of the first [x] (sent. *314a).19 Instead of observing how sweet it is to have a father who does not show anger but wisdom, the maxim states that having wisdom rather than anger is a good thing for everybody. Through minimal linguistic changes (as in [x] in place of [x]), the author of this second [x] varied the given line by generalising its content.

2 From Menander's Comedies to the Collections of Monostichs: variae lectiones as Consequences of Re-Adaptation

In such stratified collections, it is still possible to identify some gnomai which genuinely come from (and in some cases even actually are) Menandrean lines. The assumption that a [x] belongs to a play of Menander is in most cases due to the attribution to Menander of that same or similar text in the works of other authors, i.e. Plutarch, or gnomological literature like the Anthologion by Stobaeus and the Antholognomicon by Orion (these last two date to the 5th century, but they result from a gnomic tradition we can trace back to the 3rd century). These sententiae, which most likely originated from authentic lines of the poet, are the ones I examined for the purpose of my inquiry into the authorial impact of the interferences of readers and users on this material. Bearing in mind the range of alterations which the Menandri Sententiae were exposed to, we may well expect a conflictual relationship between the often-readjusted lines transmitted in the [x] tradition and those quoted by other, generally (though not always) more reliable, gnomic sources. Works like Stobaeus' Florilegium, in fact, may not be alphabetically organized (rather, thematically) nor do they only include monostichs, but the quotations are here often accompanied by the names of their authors and sometimes also by the titles of the works from which the passages were taken.20 Given this situation, the editor of Menander (and that of Euripides as well) would look for the original, unaltered text of the poet and would therefore most of the time accept and print lectiones transmitted by the other sources rather than the Menandri Sententiae. This is an undoubtedly rightful philological selection. The same perspective, however, was adopted by the editors of the Menandri Sententiae, who looked to their variants from the original as mistakes to be emended and expunged many parallel lines, believing themselves to be bringing back the ideal of the Ur-Sammlung made of intact lines of comedy and tragedy.

Sent. 622 provides an effective demonstration of the criteria according to which the [x] were edited by Meineke (1823), Jakel (1964) and even Liapis (2002). Stobaeus's manuscripts and the Menandri Sententiae's manuscripts are here the two sources for Menander's fr. 813 [x] ('where women are, there all evils are') and transmit two different lectiones; [x] and [x], respectively.21 In the last edition of the fragment by Kassel and Austin quoted here, as well in the former ones, the lectio rightly accepted in the fragment has been Stobaeus' metrically correct [x]. The same adverb, however, was also printed instead of [x] in the text of every edition of the Menandri Sententiae until 2008, as a consequence of scholars' attempt to make the [x] identical to the original texts from which they had been taken. In these editions, Stobaeus's textual tradition and the scholars' ars emendandi replace de facto the Sententiae's codices in establishing their own text. Such an operation totally refutes the 'co-authorial' role of teachers and copyists and obscures the century-old tradition of the sententiae in the lines of the plays by the original author.

In a gradual dissociation from this interpretative and editorial standpoint, in recent years huge scholarly progress has produced helpful results and materials for research into the Menandri Sententiae. Three main achievements are worth being emphasized:

• the in-depth inquiry into the educational purposes and modes of use of the Menandri Sententiae in school practices;

• the edition and re-edition of a great number of papyri and ostraka containing the [x] (principally the recent, co-written volume for the Corpus of Greek and Latin Philosophical Papyri [CPF 2015]);

• C. Pernigotti's masterful edition of the Menandri Sententiae which came out in 2008. The improvement of this edition consists of Pernigotti's new methodological approach, which aims to present the [x] as they were read, copied, and used in the Menandri Sententiae tradition. This means that he does not emend the [x] containing either indifferent or meaningful textual variants from the original, authorial lines, he does not correct the metrically wrong sententiae, and he includes the maxims created as variations of other [x]. The impact on the Sententiae of the many hands through which the collections passed needs to be recognized and made clear by printing in the very text of the maxims (instead of just in the apparatus) the final results of the intervention of those anonymous scholars and copyists whom we have called 'co-authors'.22 In fact, going back to the previous example of sent. 622. in his edition Pernigotti recovers and re-establishes in the text the lectio of the manuscripts of the Sententiae, [x].

Being now allowed to work on the sententiae standing on this philologically solid ground, the inquiry about the development of these texts may be taken a little further. After having identified the 'authors' involved and having illustrated part of the reasons for their intervention (use in schools and textual instability intrinsic to the genre), I will now attempt to analyze how the sententiae were altered.23 To reach reliable conclusions, I made a complete comparison between the texts transmitted in the collections of Menandri Sententiae and the similar ones which presumably are Menandrean (that is, lines of the poet's better preserved plays as well as lines Kassel and Austin published as authentic fragments of Menander's comedies).24 The results consist of a typological classification of the variations, which is structured in three main categories. Each category contains related typologies of variants, which will be synthetically exposed and exemplified with some fragment-sententia pairs.25

2.1 Typologies of Variants

The first category includes linguistic alterations. They represent the less evident divergences since they cannot always be plainly ascribed to a conscious intentionality of the copyists, but are still clear signals of an adaptation process. These alterations may consist of synonymic replacements, and their connection with the long tradition of the Sententiae is particularly evident when manuscripts bear a different text from papyri and Stobaeus alike. In fact, in the majority of cases papyri display the same lectio which Stobaeus transmits and which most likely was in the original Menandrean text, too. Therefore, the papyrus tradition of the [x] proves to be closer to the original nucleus of maxims excerpted from the poet's works, while the manuscript tradition of the Menandri Sententiae bears signs of use and contains variants.26

Even minor cases of language alterations, mostly made automatically and with no intention of modifying the meaning of the maxim, are small linguistic updates which facilitate the fruition of the [x] in the later centuries of circulation of the collections. Among them, we can mention [x] instead of [x].27

Other, more substantial forms of linguistic simplification, aiming for a more immediate comprehension of the moral content of the maxim, concern morphological agreement and word order. As for the first one, the change from the neuter adjective in the original line to the adjective agreeing in gender with the noun is very common in the sententiae. For example, in the case of fr. 808 [x],28 Menander's neuter [x], which gives the meaning 'what an unreliable thing is women's nature', was replaced in sent. 860 (codd. K V [of the b family], codd. Plan.) by the feminine [x], agreeing with [x], obtaining the more direct 'how unreliable is women's nature'.29 A similar call for more clarity may cause a re-disposition of the elements in the sentence, an operation which implies a clear intentionality from the writer. For example, starting from Men. fr. 720 [x]30 the morphological agreement between the initial adjective [x] and the final substantive[x] was made more easily recognizable in sent. 206 by transferring [x] to the second position, right next to its adjective, avoiding the hyperbaton and obtaining: [x]; as a result, the maxim is not a regular iambic trimeter.

Turning now to more significant categories of variations, the second typology pertains to the formal and stylistic features of a [x]. As the definition [x], valid for every Menandrean maxim, states, an essential characteristic of the Sententiae is their being complete in terms of both content and grammar in one iambic trimeter. As a consequence of this intrinsic condition, teachers and pupils, or Mediaeval compilers, who added new material to the collections by adapting or creating new maxims, were forced to re-cast into a freestanding monostich the two or more lines (or an incomplete one) from which they were deriving the [x]. An example of this adjustment applied to Menander's text is sent. *929 [x], which was derived from the second line of Arrephoros (or Auletris) fr. 70 [x].31 In the text of the poet, transmitted by ps.- Justin,32 the complete sentence is: [x] ('the intellect is god speaking'). When it was made a sententia, however, it is conceivable that an excerptor, consciously or not, extended that sentence by including in it the first word of the line, [x]: it belongs to the previous phrase in the Arrephoros, but was incorporated in the next one, obtaining a complete line. Thus, a new [x] was formed. To suit the new context, [x] was changed into [x], agreeing with the subject [x]. Moreover, in the same or in a subsequent alteration of the [x], the final nominative [x] was replaced by a dative, bringing about a change in meaning, since the resulting maxim can be translated as 'the sacred intellect is that which speaks to God'.33

A second stylistic trait of many exhortative gnomai is the protreptic [an utterance designed to instruct and persuade] tone conveyed by the imperative [giving an authoritative command] mode. Sent. 685 shows that it was even possible to create a [x] by introducing an imperative verb in a Menandrean line, Dysk. 797 in this case, quoted in Stobaeus' Antholgion: [x]. In fact, the narrative [x] of the poet's line was replaced by the prohibitive [x] when it was added to the Sententiae collection.34

Finally, we turn to the third category of variations, those modifying the content of the original verse. Such alterations are often the inevitable effects of the loss of the dramatic context in which the line is pronounced by a character in a play. In fact, once a line is taken out of its scene, it may appear senseless, its meaning might become unintelligible or it may contain references to characters and dialogic situations which must be removed to give the sentence that generalized addressee it needs to be introduced among the [x]. A simple example of these alterations is Epit. 704 [x] ('the only virtue is staying always away from that mad man'),35 which was included in the corpus of the [x]36 once it was deprived of the mention of [x]. In the play, with this definition Smikrines was referring to Charisius while admonishing his daughter Pamphila to leave him, the husband she loves. [x] is the text transmitted by Orion and it certainly suits the dramatic situation of the father-daughter dialogue, but it was changed into the neuter [x] when the line entered the Menandri Sententiae corpus as a generalized, self-standing statement 'the only virtue is staying always away from strangeness' (sent. 464).37 Another example of decontextualization is a famous and debated one from the Dis exapaton: fr. 3 Blanchard (= 4 Sandbach, 4 Arnott, 3 Austin) [x] ('he whom the gods love dies young').38 The line corresponds to the Latin ironic joke told by the slave Chrysalus to his old master in Plautus' Bacchides 816-7. The Plautine passage of ll. 816-21 deserves to be quoted in its full length:

quem di diligunt

adulescens moritur, dum valet, sentit, sapit.

Hunc si ullus deus amaret, plus annis decem,

plus iam viginti mortuum esse oportuit:

†terrae odium† ambulat, iam nil sapit

nec sentit, tantist quantist fungus putidus.

[Google translate: whom the gods love he dies young, while he is strong, feels, and wise. If any god would love him, ten years more He must have been dead for twenty years. †The hatred of the earth† walks, he no longer knows anything and he does not feel, how much the fungus is putrid.

In these lines, the sarcastic tone used by Chrysalus in his provocation to the master becomes clear: the old Nicobulus would have died twenty years ago 'if any god had favoured him', so that he would not have become of as much value as a rotten mushroom, incapable of judgment and sense. Adopting the optic of re-use and re-interpretation to which the Menandri Sententiae were subject, scholars generally suggest interpreting the original Menandrean line according to the derisory spirit of Plautus' slave, believing it likely that, in the comic context of Menander's play, the sentence was not meant to be a disenchanted reflection on human existence, as the maxim will later be read, but a satirical remark aimed at making fun of the foolish old man.39 Once the line was de-contextualized and read as a self-standing monostich (sent. 583 [x]), its philosophic message was stripped of any irony due to its comic frame and wholly resumed the seriousness of the sense with which observations like this one had already appeared in Homer and Herodotus.60

Moreover, even leaving aside the question of the original meaning of the line in the Dis exapaton, sent. 583 displays another possible mode of content change, which is the last point of the typological analysis proposed here; Christianization, by which I mean the adjustment of a maxim in such a way that it becomes compatible with Christian morality. In this case, the Dis exapaton line was made acceptable by replacing the plural [x] of the original line with the unique Christian [x] of the [x]; in fact, the plural [x] is attested in the ancient authors (Plut., Clem. Al., Stob., schol. Hom., Eust.) and is the lectio accepted in Menander's fragment, while the singular, Christian [x] is the variant of the Sententiae manuscripts (cod. A. codd. Plan., codd. Slavic translation [286]).41 The consequent change from the plural [x] to the singular [x] makes the line metrically defective.

3 Conclusions

By considering these examples of [x] in terms of their relationship to the original Menandrean lines, I hope to have shown how deeply entrenched in the [x] tradition was the coexistence of the authoritative dignity recognized to Menander, to whom the collections were entitled, and the copyists' readiness to alter his texts. The considerations expressed aimed to improve our understanding of the genesis of the Menandri Sententiae and to increase the awareness of their function and significance for the ancient users who 'co-authored' them. In fact, variants must be regarded as the result of re-elaborations, whether minimal or considerable, and their frequency implies the opportuneness of registering them as an intrinsic feature of the Menandri Sententiae, which ought not to be emendated. These variae lectiones make the original line of the poet and the sententia two distinct texts, following distinct traditions and used in different occasions and for different goals. A maxim and the Menandrean line from which it was derived must not, therefore, be reduced to one text, and the [x] needs to be maintained as an autonomous version. The fragments of the poet's comedies certainly need to be re-established in the form we judge to be closer to their originals by choosing the 'more Menandrean' lectiones, while the texts of the Sententiae need to keep reflecting, in their manifold variants, the contributions of the 'co-authors'. This principle has recently become the cornerstone of every research on the Menandri Sententiae.

In such a scenario -- I would like to add -- the study of the most recurrent typologies of variants is of valuable help both in recognizing the lectio which probably was in the original line of Menander and in understanding the reasons behind the modifications we find in the sententia. Hence, I hope that the classification and the Menandrean examples discussed here may be used as a guideline to examine other cases (concentrating on other authors as well) and as a reminder of the necessity to always bear in mind the users' continuous efforts to make the maxims suitable to their current needs. From the point of view of alterations in accord with readers' changing needs, in fact, not only did the conformity forged by copyists guarantee that a [x] was copied and transmitted throughout the Middle Ages, but it also allowed a sententia to maintain its effectiveness as a widely shared maxim in tune with the values of the time it reflected. All the minor and significant variations I have examined enabled this fortunate work to run through so many centuries; by altering the gnomai, the 'co-authors' made them a perpetual mirror of their changed purposes, language, and values, conserving in the title little more than a memory of the consolidated authority of the 4th century BC comedy writer Menander.

_______________

Notes:

1 The [x] will be quoted according to the numeration of Jakel's reference edition of 1964, followed by Pernigotti in his updated and augmented edition of 2008. Asterisks added before the numbers of the maxims distinguish the sententiae added by Pernigotti to Jakel's corpus; the various typologies of these additions (including doubles, [x] attested in newly discovered papyri and manuscripts, sententiae extracted from the translations) are described by Pernigotti (2008) 31-33. All Menander's fragments will be referred to in conformity with Kassel and Austin's edition.

2 On such a varied tradition, cf. Pernigotti (2000); Pernigotti (2003a) 121-2: Pernigotti (2005) 420-7; Martinelli (2007) 678: Pernigotti (2008) 39-87, 101-9, 153-7; Pernigotti (2015) 111-4.

3 On this issue cf. especially the studies of Schirru (2004), from which I took the examples presented in the following note, and Schirru (2010) 215-6; concerning the relationship between the gnomic tradition and the paroemiographic [the making of collections of proverbs] tradition, cf. also Tosi (2014) and, on the practice of excerpere, Konstan (2011). Finally, cf. Schirru (2010) 223-6 for the formal features of Menander's gnomic lines.

4 See, e.g., Men. Epit. 251-3 [x]: the saying 'night brings counsel' mentioned here is already implied in Phocylides (fr. 8 D. [x]) and in Herodotus (7.12.1 [x]), even two centuries before Menander (later, the proverb was also included in paroemiographers' collections. cf. Zenob. 3.97 = Diogen. 5.95 = Apost. 7.47 = Arsen. 23.89 [x]).

5 The [x] of Georg. fr. 3.5 Blanchard (= 2.5 Sandbach, 2.5 Arnott, 1.5 Austin) [x] seems to provide an example of such fortune as its being quoted in Stobaeus, Et. M. 685 38 s.v. [x] and various scholia (schol. Hom. Od. 4. schol. Soph. OT 1191, schol. Eur. Or. 343) suggests.

6 See Meyer (1881) 402-3; Korte (1931) 716-7.

7 See in particular Ullmann (1961) 2; Pernigotti (2000) 226-8; Liapis (2002) 72: Liapis (2007) 261-2.

8 The expression was first employed by Liapis (2007) 292, who acknowledged that a reader of the [x] had 'the function of a 'co-author', or rather of a 'performer', who reformulates the text even as he reproduces it'.

9 For a general presentation of these collections of monostichs. cf. the works of Marino Sanchez-Elvira/Garcia Romero (1999) 356-60: Pernigotti (2000); Pernigotti (2003b) 187; Pernigotti (2003c) 48-49; Liapis (2007) 262-3; Pernigotti (2008) 11-16; Pernigotti (2010) 231-3; Pernigotti (2011): Nervegna (2014) 205-9: Pernigotti (2015); Martina (2016) 346-7; Piccione (2017) 6.

10 Cf. Easterling (1995) 155; Cribiore (1996) 44-45: Morgan (1998) 122-3 (see also 124-44 containing a presentation of the maxims recurrent themes and motives); Cribiore (2001) 178-9, 199-200: Liapis (2007) 287-91; Nocchi (2012); Nervegna (2014) 202-5.

11 This aspect is highlighted also by Piccione (2004) 403; Easterling (1995) 159.

12 Cf. the list of school exercises on papyri and ostraka completed by Cribiore (1997) 59 and the examples described by Funghi (2003b) 5-13.

13 See, e.g., Quint. Inst. 1.9.2-3, which conveys an idea of the importance of a skillful paraphrase of Alsop's fables and of the composition of sententiae as didactic aids; another passage, Inst. 10.5.4-5, testifies in what high regard the exercise of creative variation was held ('et ipsis sententiis adiicere licet oratorium robur et omissa supplere, effusa substringere. Neque ego paraphrasim esse interpretationem tantum volo, sed circa eosdem sensus certamen atque aemulationem' [Google translate: and to the sentences themselves it is permissible to add strength to the oratory and to supplement what has been omitted, to underline what has been poured out. Nor do I mean to be a paraphrase only an interpretation, but a struggle and a rivalry about the same senses.]).

14 Examples are P. Oxy. 42.3006 (= MS 25, see also below) and P. Mil. Vogl. 1241v (= MS 20), both from the 3rd century AD.

15 On books as vehicles of transmission of the [x] cf. in particular Pernigotti (2005) 422-3.

16 Meyer (1881) 410-7; cf. also Kock (1886) 109-13; Martinelli (2003) 23; Liapis (2007) 280-5.

17 Stob. 4.26.10.

18 For the sake of accuracy, it should be noted that Stobaeus' text slightly differs from that of the other testimonies containing the sententia: at the beginning, the Anthologian has [x] in place of [x]; the latter is the lectio that Kassel and Austin print in Menander's fragment. The facilior [x] is also attested in the Slavic tradition (cf. Morani [1996] 51).

19 [x] in place of [x] creates a metrical difficulty, because if the iota was treated as long, correptio Attica would not be observed.

Typically, in Homeric meter, a syllable is scanned long or "closed" when a vowel is followed by two or more consonants. However, in Attic Greek, a short vowel followed by a plosive and a liquid consonant or nasal stop remains a short or "open" syllable. This is called Attic correption, sometime known by its Latin name correptio Attica.

-- Correption, by Wikipedia

It is only since Pernigotti's edition (2008) that this sententia has been acknowledged as having an independent existence from the maxim transmitted by Stobaeus. As will be pointed out later, we owe to this scholar most of today's much more philologically valid and genre-consistent criteria for the constitutio textus of the [x]. Even some manuscripts containing the Slavic version of the maxim have the simplified infinitive form of the verb (cf. Morani [1996] 50-51).

20 To form a thorough picture of the contained excerpta, structure, sources, and aims of Stobaeus' Anthologion as well as of his treatment of Menander's lines see Hense (l916): Gorler (1963) 103-18, 147-9: Criscuolo (1968) 256-7: Piccione (1994); Mansfeld/Runia (1997) 204-9, 213; Piccione (1999); Piccione/Runia (2001); Piccione (2003) 241-53; Piccione (2004) 407-9; Hose (2005); Piccione (2010) 619-34; Searby (2011); Hurst (2014) 184-5 (= Hurst [2015] 47-48). It might be relevant to add that in most cases, Stobaeus did not draw his quotations from the original sources, but from pre-existent agglomerates of gnomological materials. The mutual relation between the sources of the Menandri Sententiae and Stobaeus' represents a complicated question and we usually cannot ascertain a reliable picture of filiations and relative chronologies (cf. Pernigotti [2003b] 197-202. Moreover, it should be taken into account that the anthologist does not hesitate to rearrange the materials he includes in his collection, either adjusting the grammar of a decontextualized extract, or adapting a text (by re-elaboration of its content as well as by expunction of one or more passages) to the thematic section in which he quotes it. It is therefore necessary, for the purpose of a reliable analysis, to be well aware of the difficulties entailed by the comparison between the frequently altered tradition of the Menandri Sententiae and the not always impeccable quotations of the other gnomological sources like Stobaeus' Anthologion.

21 The varia lectio [x] (without movable v) might result from a mechanical error occurred in the copying process. Regardless of its genesis, this variant spoils the iambic trimeter.

22 Pernigotti repeatedly and very persuasively gives explanations and reasons for his new approach; see in particular Pernigotti (2008) 17-18. 24-25: Pernigotti (2010) 231-3.

23 On these lines, I follow in the wake of Liapis' paper, significantly entitled How to make a monostichos, Strategies of Variation in the Sententiae Menandri (2007). In it, Liapis takes into consideration a selection of maxims derived from various authors and examines the changes they underwent to be included in the Menandri Sententiae's collections. Also, Gorler's study remains important for its programmatic intent to distinguish different degrees of similarity between the [x] and the lines given by other testimonies (see especially Gorler [1963] 122-8, 134-9). For methodologic procedures and examples of the comparison between texts transmitted by different traditions, cf. also Meyer (1881) 410-6: Kock (1886) 103-8; Grilli, (1969) 189-91; Martinelli (2003) 23-24; Martinelli (2007) 679-87; Pernigotti (2003b). As already stated, with the particular aim of investigating the issues of authorship and authority, my field of research will be limited to the sententiae presumably derived from truly Menandrean lines.

24 The list of the Menandri Sententiae I compared to Menandrean lines is in Pernigotti (2008) 574-5. In addition, sent. 222-Epit. 252; sent. 334 - fr. 794.1; sent. 877 - fr. 867 are also of interest (for the latter, see below).

25 The examples I will mention have not been discussed by the scholars listed above.

26 Two easy examples of the divergence between these traditions are fr. 790-sent. 600 and fr. 859- sent. 30. In the first case, the fragment printed in Kassel and Austin's edition is [x] and reflects the text given by Stobaeus (4.20a.20) as well as by P. Schub. 29, a papyrus from the 2nd century AD which is not a direct testimony of the alphabetically ordered Menandri Sententiae, but contains a florilegium of maxims from different authors, providing an example of the variety of gnomic anthologies in circulation at its time. All the manuscripts of the [x], including those with the redactions, present the varia lectio [x]: as for the Arabic (I 245) and Slavic (299) versions, the closeness in meaning of the two adjectives makes it difficult to infer which of them was in the Greek texts they were translated from (cf. Morani [1996] 89). The variant [x] could be an attempt to simplify the metre, since it removes the resolution; correptio Attica, however, is not observed (cf. Martinelli [2003] 24). The second example of fragment and sententiae shows the same separation between the tradition of Mediaeval manuscripts of the Sententiae and that of papyri and Stobaeus. While the codices of the [x] transmit the metrically flawed text [x] is the correct lectio accepted at the beginning of Menander's fragment, relying on Stobaeus's tradition and, even more convincingly, on the text given by P. Oxy. 42.3006 (= MS 25, col. II I. 13); this papyrus, dated to the 3rd century AD, displays a series of maxims starting with a- and represents the most relevant and direct evidence we have of a proper book of Menandri Sententiae. On the other hand, for an opposite case, where Stobaeus gives a varia lectio of the presumably Menandrean text, see above Stob. 4.26.10 with the variant [x].

27 In ancient Greek, the forms [x] definitely prevailed from the 1st century AD onwards. As for the previous centuries, [x] became more common in Attic and Koine Greek than the more ancient forms with [x] from the 4th century BC, as Attic inscriptions, Ptolemaic papyri, and codices of authors such as Xenophon, Isocrates, Demosthenes, Plato, and Aristoteles attest. Although a complete consistency should not be postulated, scholars believe that Menander and the other comic poets of his period normally wrote [x] (cf. Arnott [2002] 200 and the studies he refers to). Concerning the oscillation between the forms with [x] and those with [x] in the Menandri Sententiae tradition, one may compare, e.g. the lectio [x] (Stob. 4.44.57 (codd. A Mac]) printed in Men. Epit. fr. 6 Blanchard (= 9 Sandbach, 9 Arnott) to the variant [x] (cod. D. codd. Plan., Plut. De tranq. an. 475c; De exil. 599c. Luc. Jup. Trag. 53, Jo. Chrys. In Matt. homil. 80.771, Orion. Anth. 7.9, Stob. (cod. M], Macar. 6.62 (= Diogen. 7.38]) printed in the text of sent. 594; cf. also Men. Kol. 42 Blanchard (= 43 Sandbach, B42 Arnott, 43 Pernerstorfer; P. Oxy. 3.409 + 33.2655 [2nd cent. AD], Stob. 3.10.21.1 [cod. A]; [x]) - sent. *965 (O. Petr. Mus. 44 [= MS 27.44] r, 4 [end 5th cent. AD], Stob. [cett. codd.]: [x]; Men. fr. 752 (Stob. 3.33.2 (codd. S M]: [x]) - sent. 597 (codd. B C1 D H [of the a family] U. codd. Plan., Stob. [cod. Mac]: [x]).

28 = Stob. 4.22g.142.

29 The same replacement, in a sententia, of the neuter adjective with the form agreeing with the noun happened in sent. 42 (with [x]), originated from Men. fr. 701 (with [x]).

30 = Stob. 3.9.8.

31 The maxim is not attested in Greek, but can be inferred from the Arabic (I 174) and Slavic (164) translations (cf. Ullmann [1961] 38 ad sent. 174; Morani [1996] 59); in the Slavic version, [x] is not mentioned (sanctus enim est qui loquitur cum deo).

32 De monarch. 5 (p. 99 Marcovich).

33 On the other hand, an example of abbreviation of a Menandrean passage in order to create a monostich is identified by Liapis (2007) 269-70 in sent. 877 [x], which resulted from a substantial abridgment of the four lines of fr. 867.

34 Cf. also sent. 483 [x], in which the copyists of two codices of the Menandri Sententiae belonging to the b family (K V) changed the first person indicative [x] for the imperative [x]. The original Menandrean fr. 704 has the slightly different, metrically correct text given by Stobaeus (3.2.5): [x]. In the corrupted gnomic tradition, the two-syllable conjunction [x] was replaced by [x] (family a) or sv (family b), neither of which suits the metre.

35 = Orion Anth. 7.7.

36 In codd. A K and in the Arabic translation (I 203).

37 Two similar cases of Menandrean lines which were generalized and de-contextualized when made [x] are the well-known sent. 698 [x] (it is mentioned in a significant number of papyri: MS 5, 17; 18, 16; 28.46v, 1-2; 34, 8), derived from Kith. fr. 11 Blanchard (= 10 Arnott) [x], and sent. 53 [x], derived from Men. Epikleros fr. 129.1 [x]. The variations have been already discussed by Liapis (2007) 266-7, 271-2. On the first couple of lines he observes that 'the vocative [x] being [ ... ] too tied up to the context of the play, has been replaced with [x], also causing a slight change in the meaning (cf. also Pernigotti in CPF 2015 129-30). Concerning the second couple of lines, he underlines how the original Menandrean sentence 'may appear meaningless if taken in isolation, which is presumably what led to the substitution of [x] (Liapis also suggests some possible reasons for the uncommon definition of sleeplessness as 'the best of all things').

38 The fragment was quite popular in Antiquity: besides being included in the collections of [x], it is also quoted as a famous maxim by ps.-Plut. Cons. ad Apoll. 119e, Clem. Al. Strom. 6.2.17.6, Stob. 4.52b.27, schol. Hom. Od. 15.246 and Eust. ad loc. (1781.1).

39 Cf. Arnott (1979) 169-71: 'Far from being a sentimental sigh about the Schuberts of this world, it was part of a caustic comment by the slave Syros (Chrysalus) to Nicobulus [ ... ] about the old man's stupidity on the occasion of the first swindle'. Menander's line is also read by Handley (1968) 6: Gomme/Sandbach (1971) 125: Ferrari (2001) 950-1; Blanchard (2016) 54 n. 1 in light of the ironic meaning it has in Plautus' Bacchides. However, it must be admitted that this interpretation cannot be stated with certainty since we lack the context of the Menandrean play (for a discordant opinion about a univocal interpretation for the Greek and Latin lines cf. Gorler [1963] 11-12 and Liapis [2002] 415, who point out that the supposed dependence of the meaning of Plautus' line on that of Menander's has no solid basis).

40 Cf. Hom. Od. 15.245-7 (to which the scholion containing Menander's line refers) and Hdt. 1.31-32. See also Martina (2016) 381.

41 It may be interesting to note that the original line might be attested in a 5th century AD ostrakon as well. In fact, according to the reading of the recent editors, the plural [x] would suit the ink traces of O. Petr. Mus. 41 (= MS 28.41) v l. 11, as what follows [x] seems compatible with the omicron of oi, and not with the yap of the Sententiae manuscript tradition (cf. Funghi in Funghi et al. (2012) 59; Funghi/Martinelli in CPF 2015 219).