Chapter Two: The Oral Tradition, From "Education in Ancient India"

by Hartmut Scharfe

2002

© Copyright 2002 by Koninklije Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

On one of the main tributaries of the Ganges, a smaller river known as the Yamuna, sits the city of Delhi. Delhi is one of the oldest cities in the world. It has been continually inhabited for more than 8,000 years. The soil on the banks of the Yamuna is rich, and so, the people here have always flourished. It's in this region of northwestern India, during the period following the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization, that the earliest examples of written texts were laid down in the ancient northern language of Sanskrit. These texts began to be written around three and a half thousand years ago, and they are known as the Vedas. Unfortunately for us, many of these early texts were written on fragile, perishable substances, many of them on paper made of the bark of the Himalayan birch tree, using inks made of ash. Some of these texts, remarkably, have survived from as far back as the third or fourth centuries, but in most cases they have been lost. The oldest of these Sanskrit texts, known as the Rigveda, was probably transmitted orally from at least the second millennium BC, or more than four thousand years ago. In it is contained a poetic vision of how written language developed in this region.When in giving names, they first set forth the beginning of language. Their most excellent and spotless secret was laid bare through love. When the wise ones formed language with their mind, purifying it like grain with a winnowing fan, then friends knew friendships, an auspicious mark placed on their language.

The publication of these texts had an enormous impact. For about a thousand years after 300 BC, the language of Sanskrit, once spoken only in the north of India, would spread to eclipse all others, becoming the common language of art, science, religion, and poetry, much as Latin once was in Europe. It was in this period that the Vedic religion formed based on the script of the Vedas, and from this, after a number of adaptations and evolutions, would emerge the religion we know today as Hinduism.

-- Vijayanagara: The Last Emperors of South India, by Paul Cooper, Fall of Civilizations

CHAPTER TWO: THE ORAL TRADITION

The outstanding feature of the oldest Indian education and Indian culture in general, especially in the centuries B.C., is its orality. The Vedic texts make no reference to writing, and there is no reliable indication that writing was known in India except perhaps in the northwestern provinces when these were under Achaemenid rule, since the time of Darius or even Cyrus. Those who write down the Veda go to hell, as the Mahabharata tells us,1

1 Mahabharata XIII 24.70 vedanam lekhakas caiva te vai niraya-gaminah.

and Kumarila [700 A.D.] confirms: "That knowledge of the truth is worthless which has been acquired from the Veda, if the Veda has not been rightly comprehended or if it has been learnt from writing."2

2 Tantra-varttika 13 (p.86); p.123.20 in K.V. Abhyankar's ed., Pune 1970. Al-Biruni (Alberuni's India, trans. E.C. Sachau, London 1910, vol.1 p. 125) reported in the eleventh century: "They do not allow the Veda to be committed to writing."

Kumarila Bhatta (fl. roughly 700) was a Hindu philosopher and a scholar of Mimamsa school of philosophy from early medieval India. He is famous for many of his various theses on Mimamsa, such as Mimamsaslokavarttika. Bhaṭṭa was a staunch believer in the supreme validity of Vedic injunction, a champion of Purva-Mimamsaand a confirmed ritualist. The Varttika is mainly written as a subcommentary of Sabara's commentary on Jaimini's Purva Mimamsa Sutras. His philosophy is classified by some scholars as existential realism...

The birthplace of Kumarila Bhatta is uncertain. According to the 16th-century Buddhist scholar Taranatha, Kumarila was a native of South India. However, Anandagiri's Shankara-Vijaya states that Kumarila came from "the North" (udagdeśāt), and debated the Buddhists and the Jains in the South.

Another theory is that he came from eastern India, specifically Kamarupa (present-day Assam). Sesa's Sarvasiddhanta-rahasya uses the eastern title Bhattacharya for him. His writings indicate that he was familiar with the production of silk, which was common in present-day Assam. Yet another theory is that he comes from Mithila, which has similar culture to Assam, and produced another scholar on the subject Mandana Misra....

According to legend, Kumarila went to study Buddhism at Nalanda (the largest 4th-century university in the world), with the aim of refuting Buddhist doctrine in favour of Vedic religion. He was expelled from the university when he protested against his teacher (Dharmakirti) ridiculing the Vedic rituals. Legend has it that even though he was thrown off of the university's tower, he survived with an eye injury by claiming "if the Vedas are the ultimate then I will be spared from Death". Modern Mimamsa scholars and followers of Vedanta believe that this was because he imposed a condition on the infallibility of the Vedas thus encouraging the Hindu belief that one should not even doubt the infallibility of the Vedas.

The Madhaviya Sankara Digvijayam, a 14th-century hagiographic work on the life of Sankara, claims that Sankara challenged Bhatta to a debate on his deathbed. Kumarila Bhatta could not debate Sankara as he was punishing himself to have disrespected his Buddhist teacher by defeating him in a debate using the Vedas by self-immolation at the banks of Ganga at Prayagraj and instead directed him to argue with his student Mandana Misra in Mahiṣmati.

-- Kumarila Bhatta, by Wikipedia

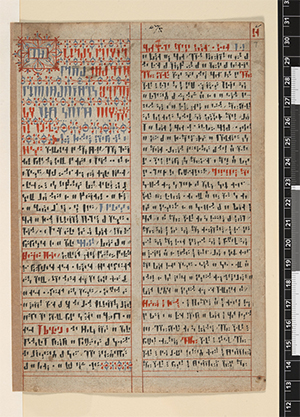

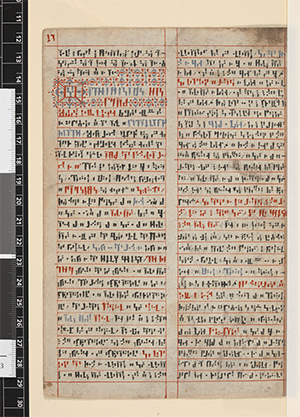

Sayana [d. 1387] wrote in the introduction to his Rgveda commentary that "the text of the Veda is to be learned by the method of learning it from the lips of the teacher and not from a manuscript."3

3 Rig-Veda Samhita, ed. F.Max Muller, 2nd ed. London 1890 (repr. Varanasi 1966), p. 14 line 15 adhyayana-vidhis ca likhita-pathadi vyavrtydhyayana-samskrtatvam svadhyayasya gamayati.

Sayana (also called Sayanacarya; died 1387) was a Sanskrit Mimamsa scholar from the Vijayanagara Empire of South India, near modern day Bellary. An influential commentator on the Vedas, he flourished under King Bukka Raya I and his successor Harihara II. More than a hundred works are attributed to him, among which are commentaries on nearly all parts of the Vedas. He also wrote on a number of subjects like medicine, morality, music and grammar...

He was the pupil of Vishnu Sarvajna and of Shankarananda. Both Madhavacharya and Sayanacharya were said to have studied under Vidyatirtha of Sringeri, and held offices in the Vijayanagara Empire. Sayanacharya was a minister, and subsequently prime minister in Bukka Raya's court, and wrote much of his commentary, with his brother and other Brahmins during his ministership...

His major work is his commentary on the Vedas, Vedartha Prakasha, literally "the meaning of the Vedas made manifest," written at the request of King Bukka of the Vijayanagara empire "to invest the young kingdom with the prestige it needed." He was probably aided by other scholars, using the interpretations of several authors. The core portion of the commentary was likely written by Sayanacharya himself, but it also includes contributions of his brother Madhavacharya, and additions by his students and later authors who wrote under Sayanacharya's name. "Sayana" (or also Sayanamadhava) by convention refers to the collective authorship of the commentary as a whole without separating such layers.

Galewicz states that Sayana, a Mimamsa scholar, "thinks of the Veda as something to be trained and mastered to be put into practical ritual use," noticing that "it is not the meaning of the mantras that is most essential [...] but rather the perfect mastering of their sound form." According to Galewicz, Sayana saw the purpose (artha) of the Veda as the "artha of carrying out sacrifice," giving precedence to the Yajurveda. For Sayana, whether the mantras had meaning depended on the context of their practical usage. This conception of the Veda, as a repertoire to be mastered and performed, takes precedence over the internal meaning or "autonomous message of the hymns."...

According to Dalal, "his work influenced all later scholars, including many European commentators and translators." Sayana's commentary preserved traditional Indian understandings and explanations of the Rigveda, though it also contains mistakes and contradictions. While some 19th century Indologists were quite dismissive of Sayana's commentary, others were more appreciative. His commentary was used as a reference-guide by Ralph T. H. Griffith (1826-1906), John Muir (1810-1882), Horace Hayman Wilson (1786-1860) and other 19th century European Indologists. According to Wilson, Sayana's interpretation was sometimes questionable, but had "a knowledge of his text far beyond the pretension of any European scholar," reflecting the possession "of all the interpretations which had been perpetuated by traditional teaching from the earliest times." Macdonnell (1854-1930) was critical of Sayana's commentary, noting that many difficult words weren't properly understood by Sayana. While Rudolf Roth (1821-1895) aimed at reading the Vedas as "lyrics" without the "theological" background of the interpretations of Yaska and Sayana, Max Müller (1823-1900) published a translation of the Rigvedic Samhitas together with Sayana's commentary....

Modern scholarship is ambivalent. According to Jan Gonda, the translations of the Rigveda published by Griffith and Wilson were "defective," suffering from their reliance on Sayana. Ram Gopal notes that Sayana's commentary contains irreconcilable contradictions and "half-baked" tentative interpretations which are not further investigated, but also states that Sayana's commentary is the "most exhaustive and comprehensive" of all available commentaries, embodying "the gist of a substantial portion of the Vedic interpretations of his predecessors." Swami Dayananda, the founder of Arya Samaj, did not give much significance to his vedic commentaries.

-- Sayana, by Wikipedia

Several reasons are given for this restriction, among them the fear that the sacred knowledge could fall into the hands of members of the lower castes, or that the student may not be fit for the sacred and supposedly powerful knowledge; the need to recite the Vedic mantras4

4 AsGS III 2,2 informs us of the correct way to recite the Veda for oneself: outside the village, on a clean spot, facing east, "looking at the point where heaven and earth touch each other, or shutting his eyes, in whatever way he may deem himself apt" (dyava-prthivyoh sandhim iksamanah sammilya va yatha va yuktam atmanam manyeta).

with correct accents and intonations, if disaster is to be avoided, reinforced the need for oral instruction.5

5 A.S. Altekar, Education in Ancient India, 6th ed., Benares 1965, p.46.

The original and most powerful—if unspoken—reason probably is the belief that the instruction in Vedic lore had always been conducted in this way, a holdover from the time when script was completely unknown in India. Some later authors6

6 D.D. Kosambi. Ancient India, New York 1966, p. 78: from the fourteenth century on. But the practice must be older, or else the condemnation in Mbh XIII 24.70 (see p. 8 fn. 1; how old this stanza is would be hard to tell) makes little sense. A manuscript of a minor Vedic text, the Naksatra-kalpa (found also in the Atharvaveda-parisista), discovered in Central Asia was dated by its editor A.F. Hoernle (JAS Bengal 62 [1893], pp.11-40) in the fifth century A.D.; H. Falk, Die Schrift im alien Indien, Tubingen 1993, p. 284. Al Biruni reported in the early eleventh century that "recently" Vasukra from Kashmir had written down and explained the Veda: Alberuni's India, vol. I p. 126. L. Renou, Classical India, vol. 3: Vedic India, p. 2 refers to an eleventh century manuscript.

permit the writing down of Vedic texts, but only as a teaching aid, for reviewing previous oral instruction.

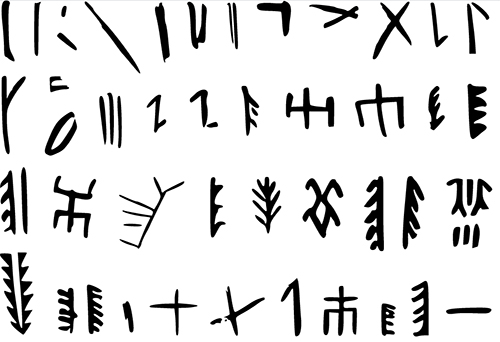

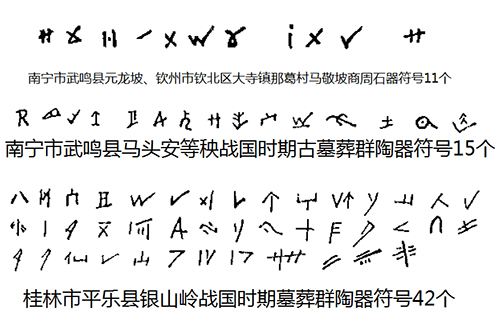

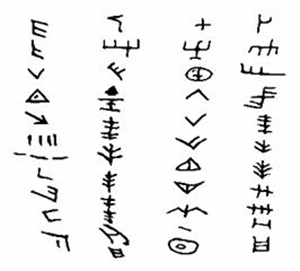

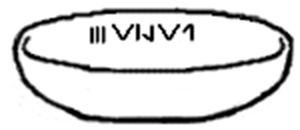

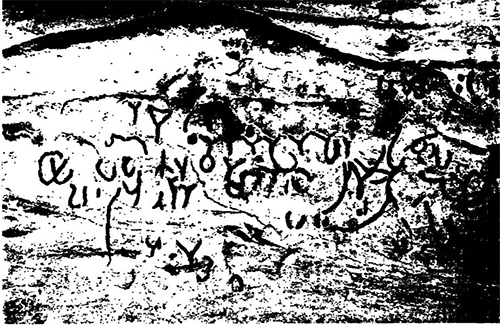

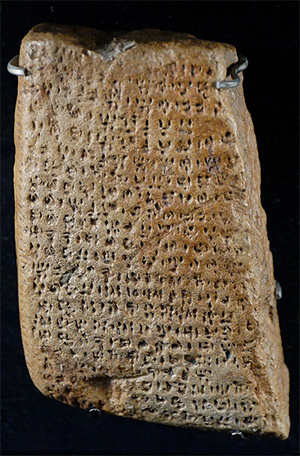

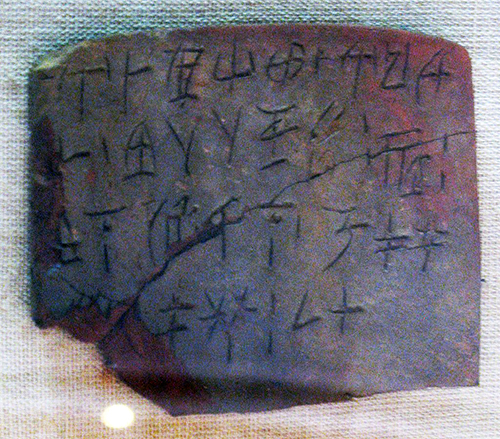

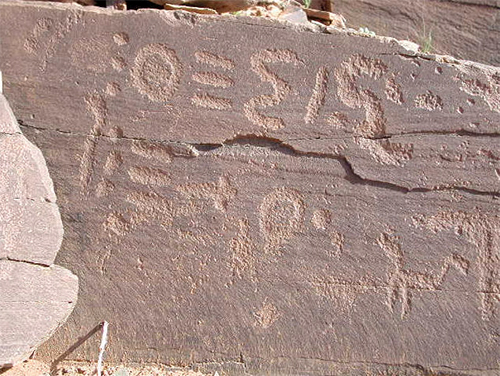

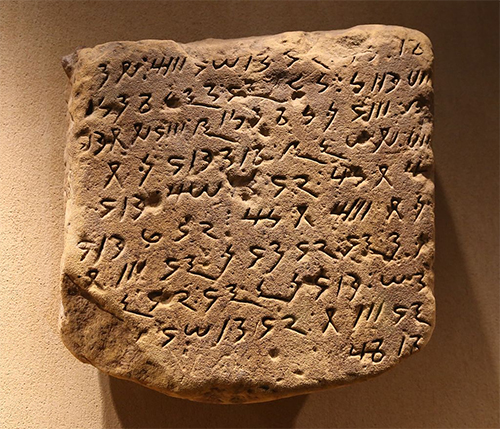

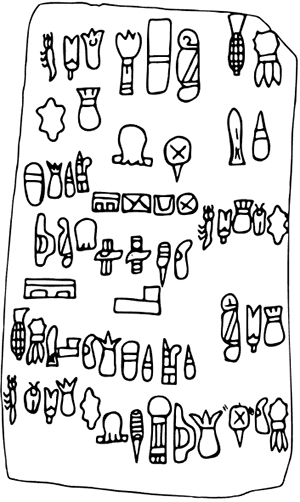

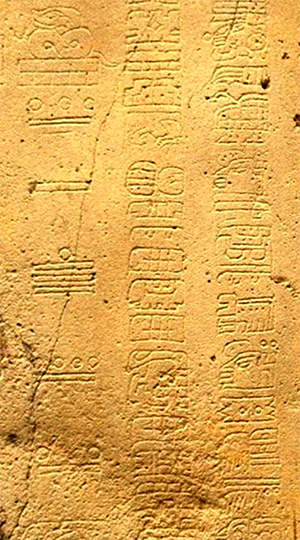

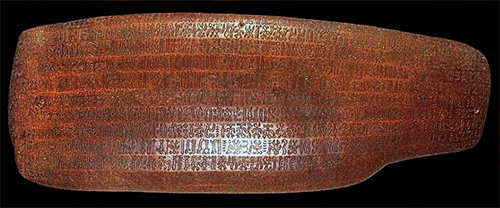

The antiquity of writing in India is a controversial topic. A script has been discovered in the excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization that flourished in the Indus valley and adjacent areas in the third millennium B.C. The number of different signs suggest a syllabic script, but all attempts at decipherment have been unsuccessful so far. Attempts by some Indian scholars to connect this undeciphered script with the Indian scripts in vogue from the third century B.C. onward are total failures.7

7 B.B. Lai, in Vivekananda Memorial Volume. India's Contribution to the World Thought and Culture, edd. Lokesh Chandra et al., Madras 1970, pp. 189-202; Kamil V. Zvelebil, Dravidian Linguistics: An Introduction, Pondicherry 1990, pp. 84-98; Gregory L. Possehl, Indus Age. The Writing System, Philadelphia 1996, reviews all recent attempts of decipherment.

Aberrations are also attempts to conclude from Rgvedic expressions like aksara8

8 J. van Buitenen, JAOS 79 (1959), pp. 176-187 argues that the meaning "syllable" is the primary meaning of the word, the others secondary, possibly by etymological reanalysis.

"immovable, imperishable, syllable, and (very much later) syllabic letter" that script was known to the authors of the Rgvedic hymns.9

9 Radha Kumud Mookerji, Ancient Indian Education, 3rd ed. Delhi 1960, pp. 227f.

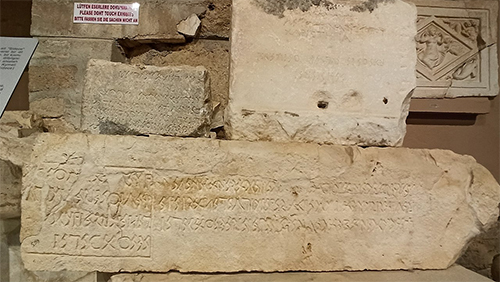

For a century the prevailing view, among Western scholars at least, was based on the studies of Albrecht Weber and Georg Buhler, who noticed the strong similarity of several letters of Asokan [Ashokan] Brahmi with letters in Phoenician and old Aramaic inscriptions, notably on the stone of Mesa dated in the eighth century B.C.10

10 Albrecht Weber. ZDMG 31 (1877), pp. 598-612 and Georg Buhler, On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet, 2nd ed. Strassburg 1898, pp. 55f. and Plate 1.

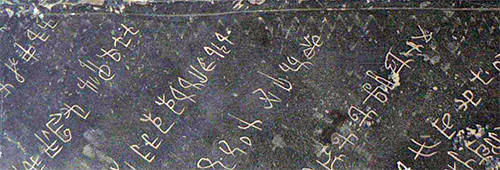

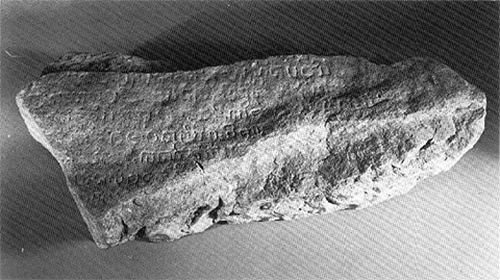

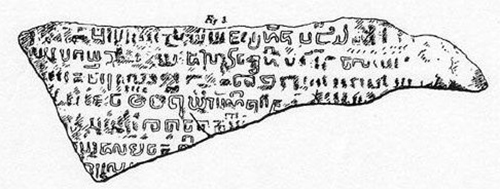

Buhler assumed therefore that the Brahmi script was borrowed from the old Aramaic script sometime in the eighth century (or at least based on it), probably for commercial purposes; it was only emperor Asoka [Ashoka] who used it for his monumental stone inscriptions and thus left us the earliest proof of Indian writing.11

The most important single error made by almost everyone in Buddhist studies is methodological and theoretical in nature. In all scholarly fields, it is absolutely imperative that theories be based on the data, but in Buddhist studies, as in other fields like it, even dated, "provenanced" archaeological and historical source material that controverts the traditional view of Early Buddhism has been rejected because it does not agree with that traditional view, and even worse, because it does not agree with the traditional view of the entire world of early India, including beliefs about Brahmanism and other sects that are thought to have existed at that time, again based not on hard data but on the same late traditional accounts. Some of these beliefs remain largely or completely unchallenged, notably:

• the belief that Sramanas existed before the Buddha, so he became a Sramana like many other Sramanas

• the belief that there were Sramanas besides Early Buddhists, including Jains and Ajivikas, whose sects were as old or older than Buddhism, and the Buddha even knew some of their founders personally

• that, despite the name Sramana, and despite the work of Marshall, Bareau, and Schopen, the Early Buddhists were "monks" and lived in "monasteries" with a monastic rule, the Vinaya

• that, despite the scholarship of Bronkhorst, the Upanishads and other Brahmanist texts are very ancient, so old that they precede Buddhism, so the Buddha was influenced by their ideas

• that the dated Greek eyewitness reports on religious-philosophical practitioners in late fourth century BC India do not tally with the traditional Indian accounts written a half millennium or more later, so the Greek reports must be wrong and must be ignored

• perhaps most grievously, the belief that all stone inscriptions in the early Brahmi script of the Mauryan period were erected by "Asoka", the traditional grandson of the Mauryan Dynasty's historical[???] founder, Candragupta, and whatever any of those inscriptions say is therefore evidence about what went on during (or before) the time he is thought to have lived

• we "know" what problematic terms (such as Sanskrit duhkha -- Pali dukkha) mean, despite the fact that their meaning is actually contested by scholars, the modern and traditional dictionaries do not agree on their etymologies or what they "really" mean, and the texts do not agree either2 [Some of these problems are discussed in Chapter Three. See Appendix C for further details.]

These and other stubborn unexamined beliefs have adversely affected the work of even the most insightful scholars of Buddhism. Yet no contemporaneous or near-contemporaneous hard evidence of any kind affirms such beliefs. Moreover, it is bad enough that such ideas have caused so much damage for so long within Indology, but the resulting misinformation has inflicted damage in other fields as well, including ancient Greek and Chinese philosophy, where the traditional construct has been used as the basis, once again, for rejecting the hard data, forcing scholars in those fields to attempt to explain away what seems to be obvious Indian Buddhist influence. This then helps maintain the traditional fiction of three totally unrelated peoples and traditions as "cultural islands" that had absolutely no contact of any kind with each other until much later times, as used to be unquestioned belief as recently as Karl Jaspers's famous book on the Axial Age, and continues, by and large, among those who follow in his footsteps....

This brings up the problem of the Buddha's birthplace. Not only are his dates only very generally definable, his specific homeland is unknown as well. Despite widespread popular belief in the story that he came from Lumbini in what is now Nepal, all of the evidence is very late and highly suspect from beginning to end. Bareau has carefully analyzed the Lumbini birth story and shown it to be a late fabrication....[Bareau (1987) (Andre Bareau, 1987. Lumbini et al naissance du futur Buddha. Bulletin de l'Ecole Francaise d'Extreme-Orient 76: 69-81. (Google translate: Lumbini et al birth of the future Buddha. Bulletin of the French School of the Far East 76: 69-81.)). The lone piece of evidence impelling scholars to accept the Lumbini story has been the Lumbini Inscription, which most scholars believe was erected by Asoka. However, the inscription itself actually reveals that it is not by Asoka, and all indications are that it is a late forgery, possibly even a modern one. See Appendix C.]...

Together it is clear that the pillars were erected first, uninscribed, and that the inscriptions were added later.

The so-called Seventh Pillar Edict on the Delhi-Topra pillar actually mentions the existence of blank pillars. The existence of uninscribed pillars has inexplicably been taken by Hultzsch, and evidently by subsequent scholars, to mean that the Buddhist Inscriptions -- which are overtly Normative Buddhist -- are earlier than the Major Inscriptions. The elaborate theory of Norman (2012) claims, among other things, that the Pillar Edicts were inscribed while horizontal, before erection; he does not mention the uninscribed pillars, nor the fact that such uninscribed pillars are actually mentioned explicitly in the "Seventh Pillar Edict" as still existing when that inscription was added to the Delhi-Topra column, nor that some still exist today. He also claims that the texts of all of the inscriptions were written out on perishable material in the capital, Pataliputra and sent out to the provinces with "cover letters" that were supposedly "not meant to be published",[This is an ad hoc proposal based on speculation; the differences are surely there in many cases because the texts were recast by the inscribers, while some of them are clear forgeries.]

despite the fact that Megasthenes visited Pataliputra in 305-304 BC and remarked that the Indians in that country did not know writing, and despite the fact that no "Asokan Inscription" has ever been found there; the written texts were then translated into local dialects, or for the Pillar Edicts, copied verbatim....

As for the minor monuments henceforth referred to as the "Buddhist Inscriptions", including the Minor Rock Edicts and Minor Pillar Edicts, a casual inspection of the inscriptional evidence and the scholarship on them might indicate that they were inscribed by Chandragupta's grandson Asoka, since the author of the First Minor Rock Edict is explicitly named "Devanampriya Asoka" in two copies of the text.

Unfortunately, we do not have rich, reliable historical sources for the Mauryas. We have only extremely tenuous information about them -- most of it about "Asoka" -- from very late Buddhist "histories", which are in large part fantasy-filled hagiographies having nothing to do with actual human events in the real world. Moreover, as Max Deeg has argued, not only did the inscriptions remain in public view for centuries, but their script and language remained legible to any literate person through the Kushan period (at least to ca. AD 250). This strongly suggests that the inscriptions influenced the legendary "histories" of Buddhism that began to develop at about that time.

That would explain why the story of Devanampriya Priyadarsi's conquest of Kalinga, his subsequent remorse, and his turning to the Dharma is all repeated in the Buddhist "histories", though they attribute the events to "Asoka", who is said to be the grandson of Chandragupta....

Despite the deep learning and care many scholars have taken with the texts, some very striking irregularities in some of the inscriptions appear not to have been noticed. Hultzsch, author of the classic monumental edition of the inscriptions, rightly notes that the Seventh Pillar Edict on the Delhi-Topra column is "unique" because unlike all the other Pillar Edicts, which (like the Major Rock Edicts) exist in synoptic copies, it is only found in a single exemplar. Salomon correctly remarks that it is "the longest of all the Asokan edicts. For the most part, it summarizes and restates the contents of the other pillar edicts, and to some extent those of the major rock edicts as well."...

Yet even a cursory inspection of the Lumbini and Nigali: Sagar Pillar Inscriptions -- both of which were discovered by Fuhrer, who was purportedly working on them when he was exposed -- shows that the Lumbini Inscription repeats exactly much of the phraseology of the Nigali: Sagar Pillar's text, but unlike the genuine "synoptic" Major Inscriptions, the phrases are not identical or closely parallel. That fact, plus the idea that an already divinized Buddha having been many times "reborn" could go back as far as the third century BC, or that anyone in the vicinity of Lumbini could have been given a Sanskrit epithet in the same period, centuries before Sanskrit is first attested in Indian inscriptions, ought to have at least aroused suspicion. Instead, scholars insist on the authenticity of all of the inscriptions, and also insist that they must all be ascribed to the ruler known from traditional -- very late, fantasy-filled, pious, hagiographical -- "histories", as well as from the Maski and Nittur Inscriptions, as "Asoka"....[The name Devanampriya Asoka occurs only in the late Buddhist Inscriptions known as the Minor Rock Edicts, specifically the Maski Inscription and the recently discovered Nittur Inscription. According to Sircar (1975), the Gujarra Inscription should be included with them, but it is extremely problematic, and seems to be a crude forgery, as discussed below. The rubbing of the Maski Inscription provided by Hultzsch (1925: 174) is very poor. Hultzsch reads Asok[a]sa 'of Asoka' without comment or explanation of the bracketed "[a]", but in the rubbing the part that includes his Asok[a] is actually written very clearly [[x] [d]eva-na[m]piyasa Asokesa, with the name in an eastern dialect form.]

the Maski and Nittur Inscriptions confirm that the texts of the Major Inscriptions (which explicitly and repeatedly say they are by Devanampriya Priyadarsi) on the one hand, and the Buddhist Inscriptions on the other, must have been promulgated by different rulers, and Devanampriya Asoka is of course responsible only for the Buddhist Inscriptions. It is time for Indologists to seriously consider the recent scholarship which suggests that some of the inscriptions are spurious....[See now Phelps (2010). Some have objected that the Lumbini pillar itself -- the stone and its preparation -- is unquestionably identical to the physical pillars used in the acknowledged Major Inscriptions. This is certainly the case. However, it is well known that there are a number of blank (uninscribed) pillars identical to pillars used in the Major Inscriptions, and the scholars who first saw the inscription on the Lumbini pillar remarked that it was remarkably clear, as if it had just been inscribed (Phelps 2010). Cf. the suspicious remarks of Schopen about the Lumbini Inscription (2004: 76-77). The inscription is also stunningly short. Even if the pillar was not recently inscribed by Fuhrer, the text itself reveals that it belongs not to the authentic Major Inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarsi, but to a much later period, no doubt exactly the period in which the legends about the Buddha's supposed birth in Lumbini were being created, as shown by Bareau (1987), who thus unknowingly -- but brilliantly -- demonstrates the lateness of the Lumbini Inscription. If he had even suspected that the Lumbini Inscription is spurious, his article would have made its case even more effectively than it does, and without the necessity of trying to explain what is patently an impossible historical background, as he actually shows very clearly. However, this topic requires much further specialized study.]

The only solution to this problem is to study the inscriptions without contaminating the data with material deriving from supposed Buddhist "historical" works such as those cited by Hultzsch....

If we were to believe Hultzsch and many other scholars, the Dipavamsa, a late Buddhist hagiographical "history", is a reliable historical work that can be trusted, so the author of the Major Inscriptions, who describes his remorse over his bloody war with the Kalingas, must be identified with Asoka. That would mean that the other set, the Later Inscriptions, which are sharply distinct in every respect, must be unidentified as to their author or authors, although unlike the Major Inscriptions they share the feature that they explicitly mention, and in most cases openly promote, Normative Buddhism. Moreover, one of the "Minor Rock Edicts" -- preserved in two apparently genuine inscriptional copies -- is clearly, explicitly said to be by Devanampriya Asoka 'His Majesty Asoka'. Accordingly, "Asoka" is the author of at least some of the later Buddhist Inscriptions, while other Buddhist inscriptions (most notably the Lumbini and Calcutta-Bairat Inscriptions) were evidently composed and erected even later. But in any case, the positive identification of Asoka as the author of the Maski and Nittur "Minor Rock Edict" inscriptions, which are radically different from any of the highly distinctive Major Inscriptions, makes it absolutely certain that "Devanampriya Asoka" cannot after all be the author of the Major Inscriptions, which explicitly and repeatedly say they are by Devanampriya Priyadarsi 'His Majesty Priyadarsi'. Considering the fact that we have absolutely no reliable historical information on "Asoka", and the fact noted by Deeg that the Major Inscriptions stood in open view for centuries after their erection and must have influenced the later writers of the Buddhist "histories" in question, it is most likely that "Asoka" was not in fact a Mauryan ruler. We do not really know when or where he ruled, if he existed at all; we do not actually know that Dasaratha was the grandson of a Mauryan ruler named Asoka; and so on....

Who, then, really was Devanampriya Asoka? The evidence suggests at least two possibilities. One is that he was imagined by the Kushan period Normative Buddhists on the basis of their understanding of the monumental Major Inscriptions erected by the Mauryas -- evidently by Amitrochates ~ Bindusara. "Asoka" was then projected back to the glorious Mauryan period as an ideal for good Kushan rulers to follow... At any rate, the inscriptions of this Devanampriya Asoka, the apparent author of some of the Late Inscriptions, simply do not have anything in common with the Major Inscriptions of the Mauryas decreed by Devanampriya Priyadarsi....

According to the traditional analysis, the single most important putative "Asoka" inscription for the history of Buddhism is the unique "Third Minor Rock Edict" found at Bairat, now known as the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription, in which "the king of Magadha, Piyadasa" addresses the "Samgha" (community of Buddhist monks) directly, and gives the names of a number of Buddhist sutras, saying, "I desire, Sirs, that many groups of monks and (many) nuns may repeatedly listen to these expositions of the Dharma, and may reflect (on them)." The problems with the inscription are many. It begins with the otherwise unattested phrase "The Magadha King Piyadasa", not Devanampriya Priyadarsi (or a Prakrit version of that name). The omission of the title Devanampriya is nothing short of shocking. Moreover, it is the only inscription to even mention Magadha. It is also undated, unlike the genuine Major Inscriptions, all of which are dated. In the text, the authorial voice declares "reverence and faith in the Buddha, the Dharma, (and) the Samgha".

This is the only occasion in all of the Mauryan inscriptions where the Triratna 'Three Jewels', the "refuge" formula well known from later devotional Buddhism, is mentioned. Most astonishingly, throughout the text the author repeatedly addresses the Buddhist monks humbly as bhamte, translated by Hultzsch as "reverend sirs". The text also contains a higher percentage of words that are found solely within it (i.e., not also found in some other inscription) than does any other inscription. From beginning to end, the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription is simply incompatible with the undoubtedly genuine Major Inscriptions. It is also evidently incompatible with the other Buddhist inscriptions possibly attributable to a later ruler named Devanampriya Asoka.

However, because the inscription is also the only putative Asokan inscription that mentions Buddhist texts, and even names seven of them explicitly, scholars are loath to remove it from the corpus. It therefore calls for a little more comment.

First, even if the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription really is "old", it is certainly much younger than the genuine inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarsi. If it dates to approximately the same epoch as the recently discovered Gandhari documents -- the Saka-Kushan period, from about the late first century BC to the mid-third century AD -- the same period when the Pali Canon, according to tradition, was collected, it should then not be surprising to find that the names of the texts mentioned in the inscription seem to accord with the contents of the latter collections of Normative Buddhist works, even though few, if any, of the texts (of which only the titles are given) can be identified with any certainty.The climate of Theravada countries is not conducive to the survival of manuscripts. Apart from brief quotations in inscriptions and a two-page fragment from the eighth or ninth century found in Nepal, the oldest known manuscripts are from late in the fifteenth century, and there is not very much from before the eighteenth.

-- Tripitaka, by New world Encyclopedia

Second, as noted above, specialists have pointed out that the script and Prakrit language of the Mauryan inscriptions continued to be used practically unchanged down through the Kushan period, and though the style of the script changed somewhat in the following period, it was still legible for any literate person at least as late as the beginning of the Gupta period (fourth century AD),[At that time the script underwent substantial changes that soon made older forms of it unreadable.]

so the inscriptions undoubtedly influenced the developing legends about the great Buddhist king, Asoka.

Thus at least some of the events described in the Major Inscriptions, such as Devanampriya Priyadarsi's conquest of Kalinga, subsequent remorse, and turning to the Dharma, were perfect candidates for ascription to Asoka in the legends. In the absence of any historical source of any kind on Asoka dating to a period close to the events -- none of the datable Major Inscriptions mention Asoka -- it is impossible to rule out this possibility. The late Buddhist inscriptions, such as the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription, may well have been written under the same influence.

Third, because the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription only mentions the titles of texts that have been identified -- rather uncertainly in most cases -- with the titles of texts in the Pali Canon, the actual texts referred to may have been quite different, or even totally different, from the presently attested ones. Because the earliest, or highest, possible date for the Pali Canon is in fact the Saka-Kushan period, the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription and the texts it names cannot be much earlier....

Among the texts considered to be identified are the Vinaya-samukasa and the Muni-gatha.

The Vinaya-samukasa has been identified with the Vinaya-samukase 'Innate Principles of the Vinaya', a short text in the Mahavagga of the Pali Canon....

Although the Buddha's own speech in this text is structured as a tetralemma, which was fashionable in the fourth and third centuries BC, it must also be noted that the tetralemma is a dominant feature of the earliest Madhyamika texts, those by Nagarjuna, who is traditionally dated to approximately the second century AD. But the problems with the inscription are much deeper than this. The Vinaya per se cannot be dated back to the time of the Buddha (as the text intends), nor to the time of Asoka; it cannot be dated even to the Saka-Kushan period. All fully attested Vinaya texts are actually dated, either explicitly or implicitly, to the Gupta period, specifically to the fifth century AD: "In most cases, we can place the vinayas we have securely in time: the Sarvastivada-vinaya that we know was translated into Chinese at the beginning of the fifth century (404-405 C.E.). So were the Vinayas of the Dharmaguptakas (408), the Mahisasakas (423-424), and the Mahasamghikas (416). The Mulasarvastivada-vinaya was translated into both Chinese and Tibetan still later, and the actual contents of the Pali Vinaya are only knowable from Buddhaghosa's fifth century commentaries."

As Schopen has shown in many magisterial works, the Vinayas are layered texts, so they undoubtedly contain material earlier than the fifth century, but even the earliest layers of the Vinaya texts cannot be earlier than Normative Buddhism, which is datable to the Saka-Kushan period. It thus would require rather more than the usual amount of credulity to project the ancestors of the cited texts back another half millennium or more to the time of the Buddha...

As for other well-known but evidently spurious "Asokan" inscriptions, note that the "Minor Pillar Inscription" at Lumbini not only mentions "Buddha" (as does, otherwise uniquely, the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription), it explicitly calls him Sakyamuni 'the Sage of the Scythians (Sakas)', who it says was born in Lumbini.

The use of the Sanskrit form of his epithet, Sakyamuni, rather than the Prakrit form, Sakamuni, is astounding and otherwise unattested until the late Gandhari documents; that fact alone rules out ascription to such an early period. But it is doubly astounding because this Sanskritism occurs in a text otherwise written completely in Mauryan Prakrit and Brahmi script. What is a Sanskrit form doing there? Sanskrit is not attested in any inscriptions or manuscripts until the Common Era or at most a few decades before it.

Significantly, the inscription also notes that the village of Lumbini is exempted from tax and has to pay less in kind as well, yet not one of the other Mauryan inscriptions includes such "benefice" information.

It is incredible that an avowedly Buddhist Inscription bestows imperial largesse on a village (though the village of Lumbini has been shown not to have existed yet in Mauryan times) rather than on a Buddhist institution.

Perhaps most telling of all, the inscription is uniquely written in ordinary third person (not royal third person) and is in the past tense. That means the text is narrated by some unknown person and does not even pretend to have been proclaimed by its putative sponsor Devanampriya Priyadarsi, the king who authored the synoptic Major Inscriptions (nor of course by Devanampriya Asoka, who may have authored the synoptic Buddhist Inscriptions). It says that it records events that supposedly happened at some time in the past, but those events have been shown to be fictitious.

The inscription is strikingly unlike the unquestionably authentic Major Inscriptions in general, and based on its contents is much later in date than it evidently pretends to be. It is a spurious inscription.

Finally, the Delhi-Topra pillar includes a good version of the six synoptic Pillar Edicts, which are genuine Major Inscriptions, but it is followed by what is known as the "Seventh Pillar Edict". This is a section that occurs only on this particular monument -- not on any of the six other synoptic Pillar Edict monuments. It is "the longest of all the Asokan edicts. For the most part, it summarizes and restates the contents of the other pillar edicts, and to some extent those of the major rock edicts as well."

In fact, as Salomon suggests, it is a hodgepodge of the authentic inscriptions. It seems not to have been observed that such a melange could not have been compiled without someone going from stone to stone to collect passages from different inscriptions, and this presumably must have involved transmission in writing, unlike with the Major Rock Edict inscriptions, which were clearly dictated orally to scribes from each region of India, who then wrote down the texts in their own local dialects -- and in some cases, their own local script or language; knowledge of writing would seem to be required for that, but not actual written texts.

For the Delhi-Topra pillar addition, someone made copies of the texts and produced the unique "Seventh Pillar Edict".[The bilingual Aramaic and Prakrit (both in Aramaic script) fragment from Kandahar known as Kandahar II or Kandahar III, which is written in an extremely odd fashion (Falk 2006: 246), has been identified as representing a portion of the "Seventh Pillar Edict" (Norman 2012: 43), but strong doubts remain about the reading of the text (Falk 2006: 246). It is also by no means exactly like the "Seventh Pillar Edict", not to speak of the peculiar presentation of text and translation. In fact, it looks like a student exercise. It is very similar to the content of the Taxila Inscription and the two Laghman Inscriptions, both of which are also highly problematic, q.v. Falk's (2006: 253) conclusion: "There is no clear evidence for an Asokan influence on this text [the Taxila Inscription]. Like the two Laghman 'edicts' this text as well could be of a rather profane nature, mentioning Asoka as king just in passing." However, Falk (2006: 241) also says of Kandahar II/III that "Asoka must have ordered to bring his words to the public unchanged regarding their sound and content. Presenting this text in two languages using one script for both is a remarkable thought, aimed at avoiding flaws in the translation." This is an unlikely speculation. Finally, the "Seventh Pillar Edict" shares some of the peculiarities of the other minor inscriptions from Afghanistan. (I.e., they are to be distinguished from the genuine fragments of a Greek translation of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Rock Edicts, found at Kandahar, q.v. Halkias 2014.) C. f. Ito (1996), a study of the Greek and Aramaic bilingual inscription from Kandahar. These texts all await detailed, serious study.]

Why would anyone go to so much trouble? The answer is to be found in the salient new information found in the text itself. It mentions a category of mahamatra officers unmentioned anywhere else, saying that they are in charge of the different sects: it names the Samgha 'Buddhists' and the Brahmanas 'Brahmanists', but also (uniquely) the Ajivikas and Nirgranthas (Jains), and "various other sects" who are unnamed.

Most incredibly, the Buddhists are called the "Samgha" in this section alone, but it is a Normative Buddhist term; the Early Buddhist term is Sramana, attested in the genuine Major Inscriptions. Throughout the rest of the "Seventh Pillar Edict" Buddhists are called Sramanas, as expected in texts copied from genuine Mauryan inscriptions....

Yet it is not only the contents of the text that are a problem. It has been accepted as an authentic Mauryan inscription, but no one has even noted that there is anything formally different about it from the other six edicts on the same pillar. At least a few words must therefore be said about this problem.

The "Seventh Pillar Edict" is palaeographically distinct from the text it has been appended to. It is obvious at first glance. The physical differences between the text of the "Seventh Pillar Edict", as compared even to the immediately preceding text of the Sixth Pillar Edict on the East Face, virtually leap out at one. The style of the script, the size and spacing of the letters, the poor control over consistency of style from one letter to the next, and the many hastily written, even scribbled, letters are all remarkable. These characteristics seem not to have been mentioned by the many scholars who have worked on the Mauryan inscriptions.

The text begins as an addition to the synoptic Sixth Pillar Edict, which occupies only part of the East Face "panel". After filling out the available space for text on the East Face, the new text incredibly continues around the pillar, that is, ignoring the four different "faces" already established by the earlier, genuine edicts. This circum-pillar format is unique among all the genuine Mauryan pillar inscriptions.

Another remarkable difference with respect to the genuine Major Inscriptions on pillars is that the latter are concerned almost exclusively with Devanampriya Priyadarsi's Dharma, but do not mention either the Sramanas ''Buddhists' or the Brahmanas 'Brahmanists' by name. This is strikingly unlike the Major Inscriptions on rocks, which mention them repeatedly in many of the edicts. In other words, though the Pillar Edicts are all dated later than the Rock Edicts, for some reason (perhaps their brevity), Devanampriya Priyadarsi does not mention the Sramanas or the Brahmanas in them. The "Seventh Pillar Edict" is thus unique in that it does mention the Buddhists (Sramanas) and Brahmanists (Brahmanas) by name, but the reoccurrence of the names in what claims to be the last of Devanampriya Priyadarsi's edicts suggests that the text is not just spurious, it is probably a deliberate forgery. This conclusion is further supported by the above-noted unique passage in the inscription in which the Buddhists are referred to as the "Samgha". This term occurs in the later Buddhist Inscriptions too; but it is problematic because it is otherwise unknown before well into the Saka-Kushan period.[This is one of the many reasons for dating all of the Buddhist Inscriptions to the Saka-Kushan period at the earliest.]

The one really significant thing the text does is to add the claim that Devanampriya Priyadarsi supported not only the Buddhists and the Brahmanists but also the Ajivikas and Jains. However, all of the Jain holy texts are uncontestedly very late (long after the Mauryan period). The very mention of the sect in the same breath as the others is alone sufficient to cast severe doubt on the text's authenticity.

The "Seventh Pillar Edict" claims that it was inscribed when Devanampriya Priyadarsi had been enthroned for twenty-seven years; that is, only one year after the preceding text (the sixth of the synoptic Pillar Edicts), which says it was inscribed when Devanampriya Priyadarsi had been enthroned for twenty-six years. The "Seventh Pillar Edict" text consists of passages taken from many of the Major Inscriptions, both Rock and Pillar Edicts, in which the points mentioned are typically dated to one or another year after the ruler's coronation, but in the "Seventh Pillar Edict" the events are effectively dated to the same year. Most puzzling of all, why would the king add such an evidently important edict to only a single one of the otherwise completely synoptic pillar inscriptions?

Perhaps even more damning is the fact that in the text itself the very same passages are often repeated verbatim, sometimes (as near the beginning) immediately after they have just been stated, like mechanical dittoisms. Repetition is a known feature of Indian literary texts, but the way it occurs in the "Seventh Pillar Edict" is not attested in the authentic Major Inscriptions. Moreover, as Olivelle has noted, the text repeats the standard opening formula or "introductory refrain" many times; that is, "King Priyadarsin, Beloved of the Gods, says" is repeated verbatim nine times, with an additional shorter tenth repetition. "In all of the other edicts this refrain occurs only once and at the beginning. Such repetitions of the refrain which state that these are the words of the king are found in Persian inscriptions. However, this is quite unusual for Asoka."

In fact, this arrangement betrays the actual author's misunderstanding of the division of the authentic Major Inscriptions into "Edicts", and his or her consequent false imitation of them using repetitions of the Edict -- initial formula throughout the text in an attempt to duplicate the appearance of the authentic full, multi-"Edict" inscriptions on rocks and pillars.

In short, based on its arrangement, palaeography, style, and contents, the "Seventh Pillar Edict" cannot be accepted as a genuine inscription of Devanampriya Priyadarsi. The text was added to the pillar much later than it claims and is an obvious forgery from a later historical period. These factors require that the "Seventh Pillar Edict" be removed from the corpus of authentic inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarsi.

The Calcutta-Bairat Inscription, the Lumbini Inscription, and the "Seventh Pillar Edict" of the Delhi-Topra pillar thus do not belong with either the authentic Major Inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarsi or the possibly authentic inscriptions of Devanampriya Asoka.[The next task is for scholars to study the spurious inscriptions to see when exactly each was inscribed, and in some cases why, so as to be able to attribute the information in them to approximately correct historical periods.]

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith

11 There is also a coin from Eran containing four letters and often dated at 350 B.C.; but the date is not at all certain.

The fatal flaw12

12 Another flaw is the fact that there is a credible likeness only between a few of the Aramaic and Brahmi letters, and that Buhler resorts for the remainder to rather fanciful distortions. But most of those who cannot accept that the Vedic tradition was oral continue to rely on his theories -- or on the even more fanciful derivation of the Brahmi script from the script of the Indus Valley Civilization.

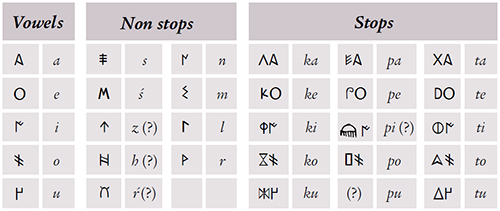

of this theory is the exact phonemic character of the Brahmi script which assigns one and only one letter to each phoneme of the Sanskrit language (or Middle Indic, in the case of Asoka [Ashoka]). This would be a dramatic improvement over the Aramaic script that leaves vowels usually unmarked and has no devices to mark the Indian aspirate stops, whereas the Brahmi script matches the phonemic analysis which had been perfected in the Vedic schools in their effort to preserve the exact pronunciation of the Vedic hymns -- but these Vedic schools had no use for a script! Why would then, as the theory goes, Indian merchants modify the Aramaic script so as to conform to the phonetic theory of the Veda reciters?

In a daring approach, J. Bronkhorst13

13 J. Bronkhorst, IIJ24 (1982), pp. 181-189.

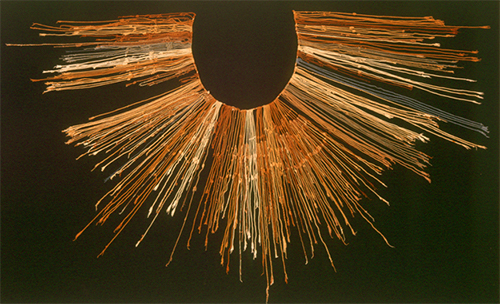

has recently argued that the padapatha of the Rgveda (a form of recitation in which each stanza is broken up into its individual words) was perhaps a clumsy attempt (in the eighth or seventh century B.C.) to write the Rgveda text down. But he has to assume that Indians soon afterwards changed their mind about such use of writing, while they added several more distorted forms of recitation: e.g., the kramapatha14

14 G.V. Devasthali, ABORI 58/59, Diamond Jubilee Volume (1978), pp. 573-582.

that "steps" as it were haltingly through a stanza -- all mnemotechnic devices to insure the integrity of the original text. It appears also that the Brahmi script was created for a language that had lost the old vocalic r and l sounds, since the post-Asokan [Ashokan] letters for these sounds are derivatives of the letter a with attached hooks; the same may be true for the letters for ai and au that are derived from the letters for e and o with additional strokes.15

If the Brahmi alphabet had been created for writing Vedic texts (for whom these additional letters are needed), we would have to assume a break in tradition, causing the loss of the original letters for r, l, ai, and au and a later reinventing of these letters.16

16 The incidence of these vowels in initial position is not high, and thus the first attestations in Sanskrit inscriptions and manuscripts are rather late: G. Buhler, Indische Palaeographie, Strassburg 1896, Tafeln 4-6 and On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet, Strassburg 1898, pp. 34f.; R. Salomon, Indian Epigraphy, pp. 30, 34.

Sanskrit is not attested in any inscriptions or manuscripts until the Common Era or at most a few decades before it.66 [66 Bronkhorst (2011: 46, 50), who cites Salomon (1998:86) on the existence of four inscriptions ascribed by some, including Salomon, to the first century BC; otherwise the earliest inscriptions in Sanskrit are from Mathura in the first and second centuries AD (Salomon 1998: 87).]

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith