by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/17/21

[O]ne of Prinsep's helpers in Calcutta was a young engineer officer named Alexander Cunningham, who in the 1850s began a systematic search to rediscover the ancient Buddhist sacred sites, beginning with Sarnath, the scene of Buddha Sakyamuni's first sermon, known subsequently among Buddhists as the First Turning of the Wheel of the Dharma.

Cunningham's work was greatly assisted by the appearance of French translations from the Chinese of accounts of journeys into India made many centuries earlier by Chinese Buddhist monks. The first of these to become accessible in the West was written by the greatly revered scholar monk and collector of Buddhist texts who first became known in the West as Yiouen Tsang, Yuan Chwang or other variations of that name -- now standardised as Xuanzang. The Orientalist Stanislas Julien's French translation of Xuanzang's journey appeared in 1853 as Voyages du pelerin Hiouen-tsang. The book set out in great detail how the Chinese monk had reached India in 631 CE after a long and perilous journey across central Asia. He had then spent some fifteen years on the sub-continent, travelling from one Buddhist location to another before settling at the great Buddhist monastic university of Nalanda, where he spent two years studying the sutras. Xuanzang had kept a detailed record of where he went and what he saw and, crucially, how he got there, which on his return to China he set down in his Journey to the West in the Great Tang Dynasty.

With Julien's French translation in his hands Alexander Cunningham was able to locate and excavate a great many ancient cities and locations associated with the Buddha, most notably at Rajgir, the ancient Rajagriha of Gautama Sakyamuni's royal patrons King Bimbisara and his cruel son Ajatashatru. Here the first Buddhist monastery had been built and the First Buddhist Council held after the Buddha's Maharaparinirvana. After his retirement from the Indian Army in 1861 as a Major-General, Cunningham returned to India to become Director-General of the newly established Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). In 1863 the directions supplied by Xuanzang led Cunningham to Sahet-Mahet, north-west of the town of Balrampur, in the Gonda District of Oude and just over sixty miles due west of Birdpore. Contained within a massive brick wall three miles in circumference were the ruins of what was clearly an ancient city now covered in dense forest. After cutting a series of tracks through the jungle Cunningham excavated some of the larger mounds, which revealed themselves to be the remains of stupas built of fired brick, together with attendant monasteries. A magnificent standing Buddha was also uncovered, with a damaged inscription at the base which included the word 'Sravasti.' More stupas and viharas were unearthed just south of the city walls, which Cunningham concluded had to be the Jetavana Garden, the monastic centre that had served the Buddha and his disciples for so many years as their summer rains retreat.

Indian archaeology then suffered a second setback in 1865 when the ASI was disbanded for financial reasons, but five years later Cunningham returned to India as Sir Alexander Cunningham, KCIE, to resume his work as the revived ASI's director. In 1873 he made a second visit to the Sahet-Mahet site which only strengthened his opinion that this important site had to be Sravasti and its associated monastery of Jetavana, as seen and described by Xuanzang more than fourteen centuries earlier.

Cunningham's main efforts thereafter were concentrated elsewhere, initially in the Sanchi area near Bhopal in central India and latterly at Bodhgaya, the seat of Sakyamuni's enlightenment, where he has to take some responsibility for the botched reconstruction of the Mahabodi temple we see today. The work of tracking down the remaining lost sites of Buddhism was now delegated to Cunningham's assistants, one of whom was the eccentric Archibald Carleyle, who soon after his arrival in India chose to add another 'I' to his name and spell it 'Carlleyle.' His main claim to fame today is his pioneering work on India's prehistory, but in the cold weather months of 1874-75 and 1875-76 Carlleyle travelling through northern Bihar and what had now become the united provinces of the North-Western Provinces and Oude (NWP&O). His first tour took him to the lake of Buila Tal, fifteen miles north-west of Gorakhpur, first noted by Buchanan in 1814. Here his exploration of the site was greatly impeded by the hostility of the local people who were determined to destroy whatever he uncovered. 'This,' he reported, 'is the invariable policy of the brutish, ignorant, and evil-disposed natives of this part of the country, who have, moreover, already destroyed some ancient monuments since I have been here, simply because they knew I wanted to preserve them.'

Despite the local hostility Archie Carlleyle was able to convince himself that what he saw beside the lake at Buila Tal matched the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang's descriptions of Kapilavastu, the city in which the young prince Siddhartha had grown up. General Cunningham then visited the site himself. 'The result of my examination,' he concluded, 'was the most perfect conviction of the accuracy of Mr. Carlleyle's identification of Bhuila Tal with the site of Kapilavastu, the famous birthplace of Sakya Muni.'

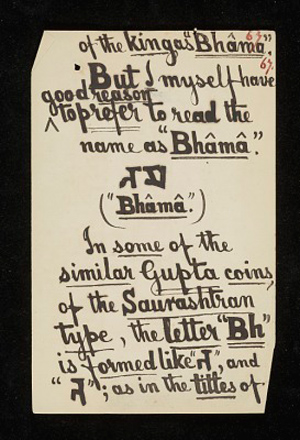

A year later Carlleyle did even better when he located the ruins of Kushinagara, the scene of Sakyamuni's Maharaparinirvana and cremation, which he placed near Kasia, thirty-three miles due east of Gorakhpur in a 'great long mound of ruins called the Matha Kunwar ka kot' -- in other words, the fort or abode of Matakumar, the chieftain or prince described to Buchanan in 1814 as 'a person of the military order.' Here Carlleyle had the enormous satisfaction of finding precisely what he was looking for: 'The famous colossal statue of the [Mahapari-] Nirvana of Buddha' -- famous, because this was what the Chinese traveller Xuanzang had seen and described in the course of his visit to Kushinagara some twelve centuries earlier. 'After digging to a depth of about 10 feet,' wrote Carlleyle in his report to Cunningham, 'I came upon what appeared to be the upper part of the legs of a colossal recumbent statue of stone ... I then hurried on the excavations, until I had uncovered the entire length of a colossal recumbent statue of Buddha, lying in a chamber.'

Archibald Carlleyle's rebuilt Buddha Maharaparinirvana statue at Kasia, the ancient Kushinagara, drawn by his draftsman Ram Narayan Bhaggat. (IOL, BL)

Much of the statue was damaged but further excavation uncovered most of the missing parts, which Carlleyle restored with the aid of Portland cement. In his enthusiasm for reconstruction, he went on to paint the statue as he thought it ought to be: 'I coloured the face, neck and hands, and feet a yellowish flesh colour, and I coloured the drapery white; and I also gave a black tint to the hair. Thus I really made the statue as good and as perfect as ever it was -- or perhaps even better than it ever was.' Carlleyle then rebuilt the temple that had held the statue, adding a vaulted roof to his own design, after which he affixed a large notice above the Maharapari nirvana statue, proclaiming himself its finder and restorer. He concluded his report to Cunningham by explaining that all this had been done at his own expense and that he was now out of pocket to the tune of 1,200 rupees. 'And finally to all I would say,' he ended, 'Let those who cavil come and see the complete work with their own eyes, and then I shall be satisfied!'

But this was not the full extent of Carlleyle's triumphs. From Kushinagara he led his survey party eastwards across the Gandak River into northern Bihar and to the district town of Bettiah, not far from which stood the two inscribed Asokan pillars first observed and reported upon by Brian Hodgson some forty years earlier: one at Lauriya Araraj, twenty miles south east of Bettiah; the other at Lauriya Nandangarh, fifteen miles north-west of Bettiah. Here Carlleyle encountered a party of Tharu tribesmen who told him that in their home country to the north there was 'a stone sticking in the ground which they called Bhim's Lat, and which they said resembled the top or capital of the pillar at Laoriya.' Guided by the Tharus, Carlleyle hurried northwards some twenty miles, 'although I had heard that the locality was most unhealthy, and a most dangerous place for my native servants.' Half a mile outside the little village of Rampurva he came upon 'the upper portion, to about 3 feet in length, of the capital of a pillar ... sticking out of the ground in a slanting position, and pointing towards the north.' With the Tharus' help he managed to expose the upper part of the pillar to a length of about forty feet. The ground was too waterlogged and the stone column itself too heavy to be moved so he had to content himself with an imperfect impression of the Asokan edict it carried, achieved by his men 'standing up to their waists in water.'

The Rampurva edict turned out to be identical in lettering and content with the inscription carried on the Lauriya Nandangarh pillar, which led Carlleyle to propose that Emperor Asoka had erected these pillars to mark his royal pilgrimage:Four different pillars of Asoka are now known to be situated along the line of the old north road which led from Magadha to Nipal, or from the Ganges opposite Pataliputra or Patna, through Besarh or Vaisali, in a northern or rather north-north-westerly direction, keeping at a moderate distance to the east of the Gandak, to the Tarai and hills of Nipal ... The fourth pillar is the fallen and buried pillar discovered by me close to Rampurva. 21-1/2, to the north-north-half-north-east from the pillar at Laoryia Naondangarh ... Now it is evident that the inscriptions on these pillars were intended to be read by passing travellers and pilgrims passing along the old north road from the Ganges opposite Pataliputra to Nipal. I should therefore expect to find either another pillar. or else a rock-cut inscription, still further north somewhere in the Nipal Tarai.

The Rampurva Asokan pillar, first uncovered close to the Nepali border by Archie Carlleyle in 1876, but not fully excavated until 1904, when its missing lion capital (upper left) was located -- and when this photograph was taken by John Marshall. (IOL, BL)

With the publication of the ASI's annual report for 1876 it seemed that all the major Buddhist sites had been satisfactorily located. Much of Carlleyle's field-work thereafter was taken up with palaeontology in the wild hill country known as Bundelkhand but already his behaviour had become increasingly irrational and in May 1885 Sir Alexander Cunningham ordered his compulsory retirement at the age of fifty-four.

-- The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer: An Archaeological Scandal, by Charles Allen

[x]

Archibald Campbell Carlyle (1831–1897)[1] was an English archaeologist active in India.

The Archaeological Survey of India was revived as a distinct department of the government and Sir Alexander Cunningham was appointed as Director General, taking office in February 1871. Cunningham was given two assistants: J. D. Beglar and Carlleyle. They were later joined by H. B. W. Garrik. Carlleyle handled the Agra region for the Report of 1871–72, while Beglar was responsible for Delhi.

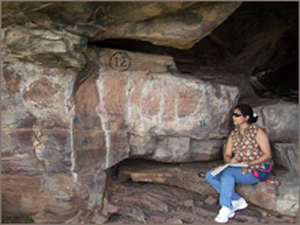

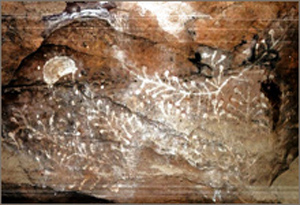

In 1867–68, Carlleyle discovered paintings on the walls and ceilings of rock shelters in Sohagighat, in the Mirzapur district. He was the first to claim a Stone Age antiquity for these. He also made many other important contributions to archaeology in India.[2][3] He is credited with finding of 20 copper and 4 silver punch-marked coins at Bahraich, near the ancient city of Benaras (modern Varanasi).[4]

References

1. Kennedy, Kenneth A. R. (2000). God-Apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia. University of Michigan Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-472-11013-1.

2. Kennedy, Kenneth A. R. (2000). God-Apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia. University of Michigan Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-472-11013-1.

3. Bhattacharyya, Narendra Nath (1993). Buddhism in the history of Indian ideas. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 27. ISBN 81-7304-017-6.

4. Imperial Gazetteer of India (1909) Published by Oxford University. V. 2, P. 152

External links

• Works by or about A. C. L. Carlleyle at Internet Archive

*********************************

The Rock Art of India [Excerpt]

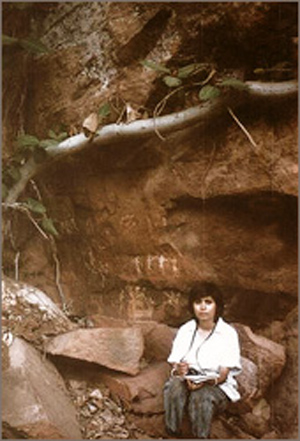

by Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak

Bradshaw Foundation

Accessed: 3/18/21

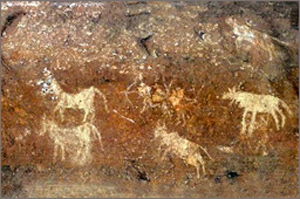

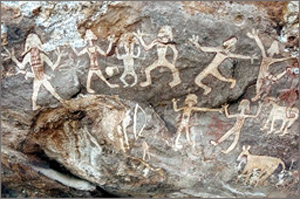

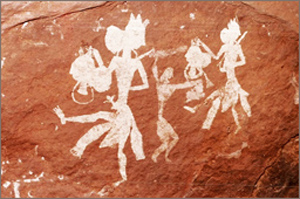

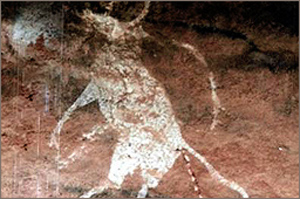

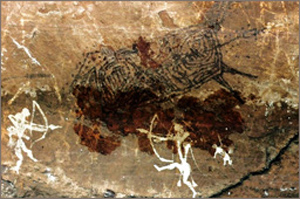

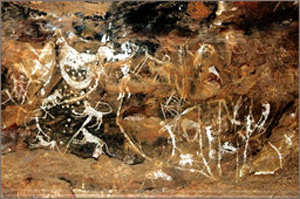

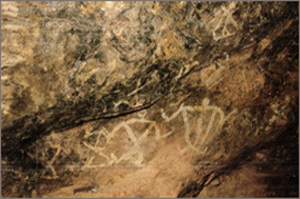

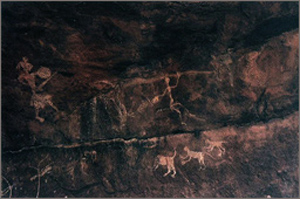

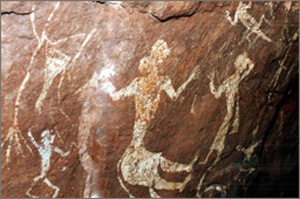

The earliest discovery of prehistoric rock art was made in India, twelve years before the discovery of Alta Mira in Spain. Archibald Carlleyle discovered rock paintings at Sohagihat in the Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh in 1867 and 1868. Unfortunately he did not publish. J Cockburn rightly commented that Carlleyle’s knowledge died with him (Smith, 1906: 187). Fortunately, Carlleyle had placed some of his notes with a friend, Reverend Regionald Gatty, and V A Smith published these later, which is the only record of his discovery of Rock paintings. In his note he wrote “Lying along with the small implements in undisturbed soil of the cave floors, pieces of a heavy red mineral-coloured matter called geru were frequently found, rubbed down on one or more facets, as if for making paint. Geru is evidently a partially decomposed hematite (Iron peroxide). “On the uneven sides or walls and roofs of many caves or rock shelters, there are rock paintings apparently of various ages. Though all evidently of great age, done in red colour called geru. Some of these rude paintings appeared to illustrate in a very stiff and archaic manner scenes in the life of the ancient stone chippers. Others represent animals or hunts of animals by men with bows and arrows, spears and hatchets. With regard to the probable age of these stone implements I may mention that I never found a single ground or polished implements not a single ground ring stone or hammer stone in the soil of the floors of any of the many caves or rock shelters I examined.” (Smith 1906: 187).

*********************************

Prehistoric India at Manchester Museum I: Archibald Campbell Carlyle

by Bryan Sitch, Deputy of Head of Collections

Manchester Museum

June 23, 2017

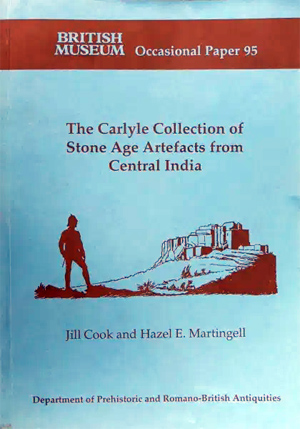

Cover design of British Museum occasional paper about the Carlyle collection (1994)

Manchester Museum is working on an HLF Courtyard extension project that opens in 2020, and collections curators are looking through their collections for anything that comes from the Indian subcontinent in preparation for the new South Asia Gallery. The new gallery will comprise eight ‘chapters’ ranging chronologically from prehistoric times to Partition, the diaspora and the founding of South Asian communities in the UK, especially Manchester. All of the disciplines represented in the Museum collections are contributing to this exciting project and doubtless other curators will report in due course about what they have in their collections. In the archaeology collection it’s been an exciting journey of discovery and revelation as I began to realise how significant some of the collectors and donors represented in Manchester Museum’s collection were in the history of Indian archaeology.

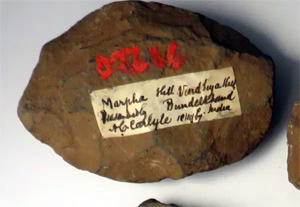

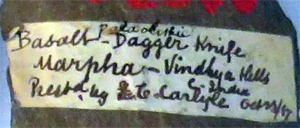

Palaeolithic stone tool from the Vindhya Hills, India with a A.C.Carlyle label (Manchester Museum)

Detail of a Carlyle label (Manchester Museum)

Perhaps the most important of the collectors who gave us material from the Indian sub continent was Archibald Campbell Carlyle (1831-1897). Carlyle (or Carlleyle) was First Assistant to the Archaeological Survey of India from 1871 until his retirement in 1885. Carlyle went to India to seek his fortune, initially as a tutor. At this time employment in the colonies offered security and career prospects. Carlyle worked in the Indian Museum in Calcutta, the Riddell Museum in Agra and then joined the Archaeological Survey of India. He was appointed by Alexander Cunningham (1814-1893), Director General of the Survey. The Archaeological Survey was part of the British imperial and colonial project in India, to survey, record, and catalogue the antiquities of the country in order to understand, administer and control them more effectively. As Dilip Chakrabarti puts it: Cunningham ‘…was trying to justify the systematic archaeological exploration of India on the grounds that politically it would help the British to rule India.’ (see Prof.Chakrabarti’s ‘The development of archaeology in the Indian subcontinent’, in World Archaeology 13.3, Feb.1982).

Upinder Singh’s book The Discovery of Ancient India Early Archaeologists and the Beginnings of Archaeology (Permanent Black, 2004) and a British Museum occasional paper on The Carlyle Collection of Stone Age Artefacts from Central India by Jill Cook and Hazel Martingell (1994) provide a lot of information about Carlyle from which the following summary is extracted.

Occasional paper about the Carlyle collection at the British Museum

At a time when Cunningham and the other assistants were understandably preoccupied by ancient Indian sculpture, temples and coins, Carlyle was one of the few people making an effort to recover and record prehistoric stone tools. Jill Cook and Hazel Martingell’s occasional paper paints a vivid picture of Carlyle as a field archaeologist sleeping rough in ruined temples and upsetting the polite conventions of Raj society, on one occasion threatening an enquirer sent by the Raja of Nagod with a gun. Carlyle seems to have been rather prickly about his status, which may explain the alternative spelling of his name as Carlleyle, to suggest he was from an aristocratic family. His ‘psyche-evaluation’ described him as ‘not ordinarily insane, but liable to outbursts of eccentric action and evil temper’ (Cook and Martingell:13).

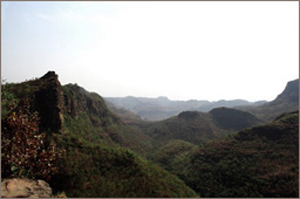

The work took Carlyle into the landscape for long periods at a time, travelling on horseback, accompanied by servants on foot and camels to carry the baggage and surveying equipment. He was in eastern Rajastan in 1871-3, the Vindhya Hills and then northwards into the plains with seasons in Gorkhpur, Saran and Ghazipur during the 1870s. He excavated a site at Joharganj in 1879. In the early 1880s he worked in the Vindhya Hills again when complaints were made about him. As Cook and Martingell put it: ‘In 1882, a European with one servant, living rough, without bed and bedding and without a change of clothes or proper food for six weeks had to be mad.’ There is more than a hint of the Indiana Jones about him.

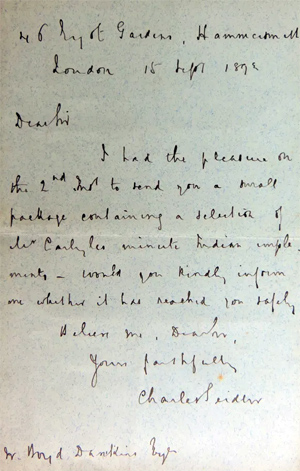

Charles Seidler’s letter in Manchester Museum

When Cunningham proposed that the Archaeological Survey be disbanded, Carlyle lost his job and came back to Britain in 1885. He was 54. Living in straitened circumstances in London, Carlyle disposed of his archaeological collection by sale or by donation to a number of museums and individuals. A dealer in antiquities, Charles Seidler, wrote letters to collectors including Sir John Evans, and Canon Greenwell, antiquarian societies, and the Manchester Museum. David Gelsthorpe, Curator of Palaeontology, found some archive correspondence from Seidler relating to the sale of prehistoric stone artefacts from Carlyle’s collection (see image above). The slips of paper that accompany the letter give details of the objects and where they found. Presumably, the various objects were wrapped in these slips of paper. This information was used to compile the entries in the Manchester Museum accession register (the ‘O’ register) and from these we learn that some of the flints came from a very important site called Morhana Pahar in Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh. Bridget Allchin identified this as one of a group of sites in the Vindhya Hills escarpment overlooking the Ganga Valley about five miles north of Hanmana village near Bhainsaur. Carlyle excavated the site but didn’t publish it in full (B.Allchin and R.Allchin -1982 –The Rise of Civilisation in India and Pakistan, p.82). He may have kept the information to himself, thinking he would go back some day to investigate it in detail but his ‘retirement’ prevented further work.

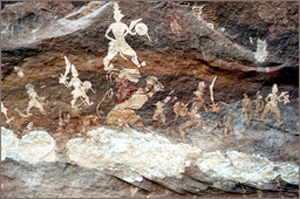

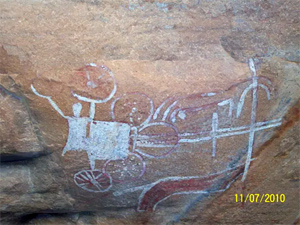

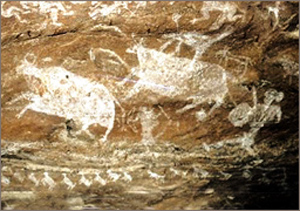

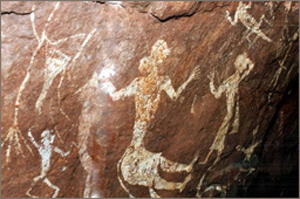

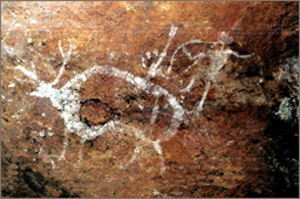

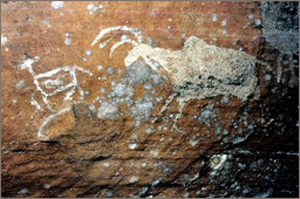

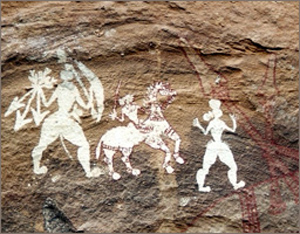

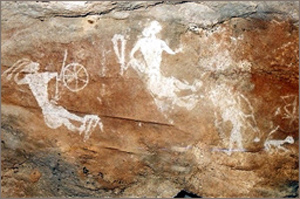

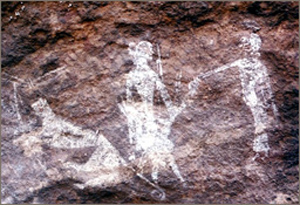

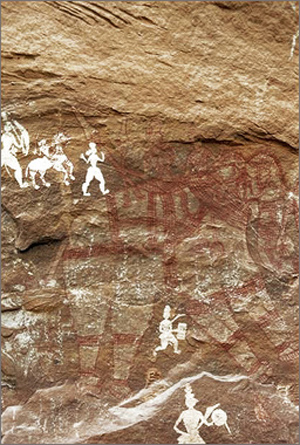

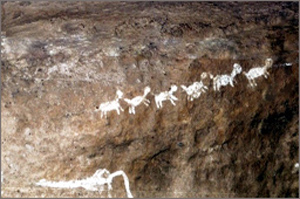

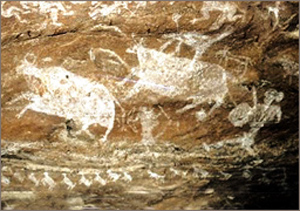

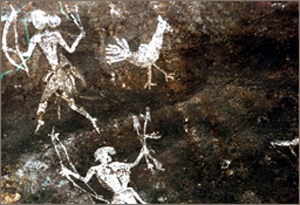

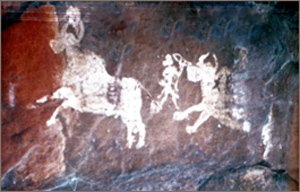

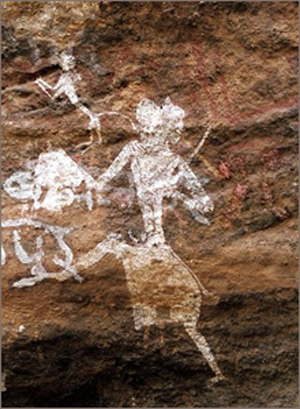

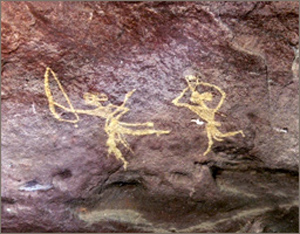

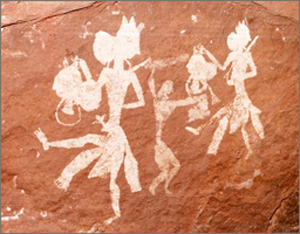

Chariot rider ambushed by bowmen at Morhana Pahar. It appears that Carlleyle painted over the original red pigment with white paint in order to capture the details photographically. Photo: courtesy of Prof Ajay Pratap, Head of Dept of History, Banaras Hindu University

The cave or rock shelter site at Morhana Pahar yielded thousands of worked flints and there were cave paintings or mural art. Some of the images must have been painted later in prehistory because they show men driving chariots being ambushed by men on foot using bows. Carlyle’s notes described them as showing ‘in a very stiff and archaic manner scenes in the life of the ancient stone chippers, others represent animals or hunts of animals by men with bows and arrows, spears and hatchets…’ They seem to depict people living a hunter-gather lifestyle confronting chariot-drivers of the Indian Iron Age, so there must have been considerable overlap of what might be considered chronologically distinct material cultures. Chenchu hunter-gatherers in India were photographed during the 1930s, showing how resilient this way of life is (see Allchin and Allchin p.85). Carlyle seems to have been the first to propose that the cave art was undertaken by people in prehistory. When he was working it was commonly supposed that cave paintings couldn’t have survived for such a long time, and it was only the discovery of Altamira later in the 19th century that opened people’s eyes to the existence of prehistoric cave art. It is a shame that so far we have not been able to find a photograph of Archibald Campbell Carlyle. Over to you gentle reader….

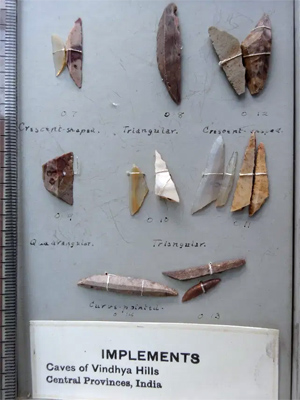

Carlyle Collection microliths from Morhana Pahar in the Vindhya Hills, in northern central India

The flints from Morhana Pahar are known as microliths and include lunates or crescent shaped artefacts, rhomboids, trapezes, trapezoids triangles, bladelets, drill points and so on. Some of them were mounted in wooden shafts to create barbed weapons. Some were found still ‘glued’ in position in their wooden armatures using bitumen at the prehistoric site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan. The tools are very small and some archaeologists assumed that the people who made them must have been themselves of small stature or pygmies, hence the name for the tools: pygmy flints. They are very similar to the stone tools found on the Pennines around Manchester and during the early 2oth century an associate of William Boyd Dawkins at Manchester Museum, Revd Gatty, argued that northern Britain had been settled by so-called pygmy people from northern India! The flints date from the Mesolithic period, c.9,000-4,000 BC.

Other material includes more microliths from Gharwa Pahari, Baghe Khor and Likhneya Pahar, Palaeolithic implements and Neolithic axeheads from Marfa in Bundelkhand, and other stone artefacts, including a Madras type hatchet from the Gaur River.

As a footnote to this discussion I might also add that the list of museums holding Carlyle material in Cook and Martingell’s occasional paper in 1994 does not include Manchester Museum. So far 82 artefacts that Carlyle collected have been catalogued, one of the largest of the collections after the British Museum and National Museums of Scotland (Edinburgh).

I leave the last words to Carlyle:

‘The question now, therefore, is not -‘where are stone implements to be found?’ but rather – where are they not to be found?’ For so far as my own experience goes, they appear findable almost everywhere in India.’

Dilip Chakrabarti (1999) India an Archaeological History Palaeolithic Beginnings Early Historic Foundations (O.U.P.), p.95

*********************************

Letter to Mr. Rivett-Carnac [Colonel John Henry Rivett-Carnac 1838-1923]

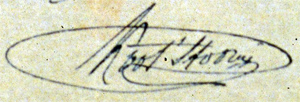

by Archibald Campbell Carlleyle

Camp, near Chapra

April 23, 1879

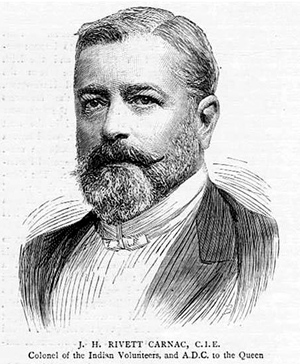

J. H. Rivett Carnac, C.I.E., Colonel of the Indian Volunteers and A.D.C. to the Queen

British employee of the Indian Colonial Service. Researched rock art in India and donated a large collection of stone tools from north-west India in 1883. From 1858-94 he worked in the Bengal Civil Service, as a secretary to R.C. Temple (q.v.). Married to Annie Marian Durant (Mrs Rivett-Carnac q.v.) in 1868.

Bibliography

https://whowaswho-indology.info/5226/rivett-carnac-h/RIVETT-CARNAC, John Henry (Harry). London 16.9.1838 — Vevey, Switzerland 11.5.1923. British Colonial Officer and Scholar of Indian Prehistory. Colonel. Son of Admiral John Edward R.-C. and Maria Jane Davis, in a family with long tradition of Indian service. In 1858–94 worked in Bengal Civil Service (i.a. as secretary to R. C. Temple), also raised and commanded the Ghazipur volunteer regiment. C.I.E. 1878. Retired and settled in Switzerland. Married 1868 with Annie Marian Durant, no children. Publications: Report on the Cotton Department: For the Year 1868-1869. 1869; . – articles on prehistoric antiquities in JASB and PrASB. – Many Memories of Life in India, at Home and Abroad. 1910. Sources: Buckland, Dictionary; H.M. Durand, JRAS 1923, 491f. (eloquent, but almost no information); https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Rivett-Carnac-25 (quoting The Spectator) with photo

-- Persons of Indian Studies, by Prof. Dr. Klaus Karttunen.

-- Colonel J H Rivett-Carnac, by The British Museum

John Henry Rivett-Carnac C.I.E. (1838 - 1923)

Colonel John Henry (Harry) "Lord Harry" Rivett-Carnac C.I.E.

Born: 16 Sep 1838 in Marylebone, London, England

Son of John Edward Rivett-Carnac and Maria Jane (Davis) Rivett-Carnac

Brother of James Davis Rivett-Carnac, Henrietta Rivett-Carnac, Anna Maria Rivett-Carnac, Elisa Mary (Rivett-Carnac) Tilghman-Huskisson, Edward Stirling Rivett-Carnac and Arthur Boileau Rivett-Carnac

Husband of Annie Marian (Durant) Rivett-Carnac — married 1868 [location unknown]

Died: 15 May 1923 in Vevey Switzerland

Biography

John Henry “Harry” was born in 1838, the second son of Admiral John and Maria Jane's four son's and seven children. In 1868 he married Annie Marian Durant but they did not have any children. He spent most of his very full and successful life in India, where he was Secretary to Sir Richard Temple, Private Secretary to Viceroy Lord Lytton, as well as holding many other distinguished posts in India. In 1894 he was appointed A.D.C. to Queen Victoria and later King Edward Vll. He retired to Switzerland, where he died in Vevey in 1923. He was a prolific writer with 52 works in 100 publications in 2 languages and with 307 library holdings. His work ranged through Bibliography, Folklore, History, Criticism and Interpretation. His best known work was "Many Memories of Life in India, at Home, and Abroad" (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1910.

The following article appeared in The Spectator in May 1923. "The death of Colonel John Henry Rivett-Carnac at Vevey (on the north bank of Lake Lausanne Switzerland) on Friday, May 11th, is a matter of especial regret to readers of the Spectator, who will remember the many letters from him that we have published. In accordance with the family tradition of the Rivetts he spent most of his life in India, where he had a very distinguished career, in both civil and military capacities. In addition to his public life in the Indian Civil Service, he had many private hobbies of a more purely intellectual nature, in any of which he would have obtained eminence had it held his somewhat over-versatile attention for longer than a few years at a time. One of the practical results of his interest in archaeology is the possession of several valuable coins by the British Museum, a gift from him. The latter part of his life, practically since his retirement, he spent in Switzerland, where he did valuable work during the War for British prisoners. His death has deprived us of one of those all too rare combinations of personal charm and practical ability." He also wrote the book - still available on Amazon - "Many Memories of life in India, at home and abroad." In 1878 he was made a Companion of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire (C.I.E.) and was Aide de Camp to both her Majesty Queen Victoria and His Majesty King Edward VII. The Times of May 14 1923 had this obituary. We regret to announce that Colonel John Henry Rivett-Carnac C.I.E V.D., distinguished member of a family famous for its service in India died on Friday at Vevey, Switzerland, aged 84. ....... He was the second son of Admiral John Rivett-Carnac, by his wife Maria, daughter of Captain Samuel Davis, who in 1799, the narrow winding staircase to the roof of Nandesur House, Benares, kept at bay, until relieving troops arrived, Wazir Ally, the deposed Nawab of Oudh, after he had massacred Mr Cherry the Resident, and most of the European inhabitants. On his fathers side Rivett-Carnac belonged to the old Suffolk family of Ryvet, or Rivett. Both his paternal grandfather , who assumed the additional surname of Carnac, and his uncle were Governors of Bombay. .. He was thus born into the innermost circle of old Haileybury Civilians, belonging to one and being closely related to another of the four families mentioned by Kipling in “The Day’s Work”, the Plowdens, the Trevors, the Beadons and the Rivett-Carnac’s.......... He was appointed to the Bengal Service..... Early training would have taught him the method and discipline he somewhat lacked to supplement his great abilities as an administrator ....... but he had influential connections ......... Appointed to the Cotton Commission ... he did very good service, writing a valuable report on cotton cultivation and trade ....." During the great famine in Behar when appointed to "purchase grain for the famine-stricken. Rivett-Carnac’s methods were lavish” and it was remarked by Lord Mayo that “if told to do a thing he could be trusted to get it done, but seldom reckoned on the expense either to himself or anyone else.”....... “He was appointed to the Benares Opium Agency - a post generally reserved for senior men. He soon revolutionised and improved the machinery.....” an impulsive man, he was apt to tire of an enterprise, and spells of strenuous official work would sometimes be succeeded by a period of lethargy. ...... he prized no distinction so much as that of Aide-de-Camp to queen Victoria and afterwards King Edward - an honour never before attained by an Indian civilian. ..... A born raconteur, as his delightful volume of “Many Memories of life in India” abundantly shows, he had an extraordinarily wide circle of friends in all classes of society. ....He married at the end of 1868, and is survived by his wife Marion, daughter of General Sir Henry Durand .... He lived some time in Suffolk, where he was Lord of the Manor Stanstead Hall, but later purchased and for years exercised generous hospitality at the Chateau de Rougement, Vaud, once a celebrated Cluny Benedictine priory, and later the Castle of the Berne Governors. But it was too great an altitude for his health and his last years were spent at the Hotel des Trois Couronnes, at vevey, where he died. My grandfather ‘Pop' was always rather scathing of “Lord Harry” despite his many achievements - and my father ‘Jack’ had this to say about him in his “Story”. “My Great Uncle Harry must have been quite an able individual and even for Victorian times was a most unmitigated snob. He was, according to some tales, always excusing himself as he had to go to see 'some Duke or Lord so and so'. One story told against 'Lord Harry’ as he was fondly known, was that around the 1890’s a certain confidence trickster was had up in London for fraud. It appeared that this gentleman, who called himself Rivett-Carnac had, among other things, chosen from a well know jeweller, various diamond rings and bracelets, which he had asked to be sent up to his hotel so that his wife could chose one for a birthday present. The jeweller most impressed, duly obliged, only to find that the rings, bracelets AND Mr Rivett-Carnac had disappeared without trace. Apparently the newspapers took up the the story with headlines “A Rivett-Carnac goes wrong. Member of a well-known Anglo-Indian family steals jewels etc.” Naturally Lord Harry was furious and wrote to the papers denying that the accused was a Rivett-Carnac, and eventually attended the court at which the accused was found guilty. This proved too much for ‘Lord Harry’ who stood up in court, and after emphatically denying that the man was a Rivett-Carnac ended by challenging him to say what right he had to use this distinguished name. Quite unperturbed, the accused rose and said, “My Lord, I am the illegitimate son of Sir Harry!

Great Uncle Harry did however make up a really good - if not thoroughly accurate record of the Family Tree, the authenticity of which he managed to get both Burkes and Debretts to accept.” My grandfather goes on to say that "It seems sad to have to accept Douglas’s more mundane, but certainly more accurate family Hat, than Great Uncle Harry’s sparkling Crown, even though most of the jewels have proved to be common glass.” Here, I would like to add that Douglas (who had our branch of the family decended from Blacksmiths rather than the Aristocracy of Lord Harry’s account) later added an apology in a Supplementary Note, which says in brief ”Proof that it listed the Derby family among relatives of the Brandeston Revetts has recently come to light” therefore “Elizabeth Rivett had every reason to believe herself entitled to adopt the Suffolk Rivett/Revett on behalf of her son Thomas” his negation of which had led him to the Blacksmith theory! After further research it can be reliably established that our branch of the family did indeed descend from the noble Derby Branch of the Rivett’s rather than the Blacksmith branch. The following is a summary of his life John F. Riddick, Who Was Who in British India (Westport, Connecticut, London: Greenwood Press, 1998), p. 308; RIVETT-CARNAC, John Henry Indian Civil Service; b 16 Sept. 1838 in London; s of Adm. John Rivett-Carnac and Maria Davis; m 1868, Marian Durand. Educ: Germany; Haileybury. 1859 joined ICS and assigned to Bengal; 1862 was Sec. to Sir Richard Temple [q.v.], Chief Comr. of Central Provinces; 1866-68 made Cotton Comr.. CP; 1872 assigned as Comr. of Cotton and Commerce. Govt, of India: made Special Comr. during Bengal Famine of 1874; 1875 was Opium Agent at Benares; 1877 selected Privt. Sec. to Viceroy Lord Lytton [q.v.J; 1885 named ADC to C-in-C. India, Sir Donald Stewart [q.v.); 1885 and 1887 led an Indian Rifle Team at Wimbledon: 1885 raised and commanded Ghazipur Lt. Horse and Rifles; 1894 named ADC to the Queen. Publications: Many Memories of Life in India, at Home and Abroad. 1910; and several Journal articles addressing mainly archaeological subjects. Honors: CEE. VD. FSA. d 11 May 1923.

Sources

[http://thepeerage.com/p55952.htm#i559520 The Peerage.com (M, #559520) Article in The Spectator Obituary in The Times of May 14 1923. Information contained in his personal "Notes on the family of Rivett-Carnac" for private circulation in 1909. John F. Riddick, Who Was Who in British India (Westport, Connecticut, London: Greenwood Press, 1998), p. 308 World Cat Identities

-- John Henry Rivett-Carnac C.I.E. (1838 - 1923), by WikiTree

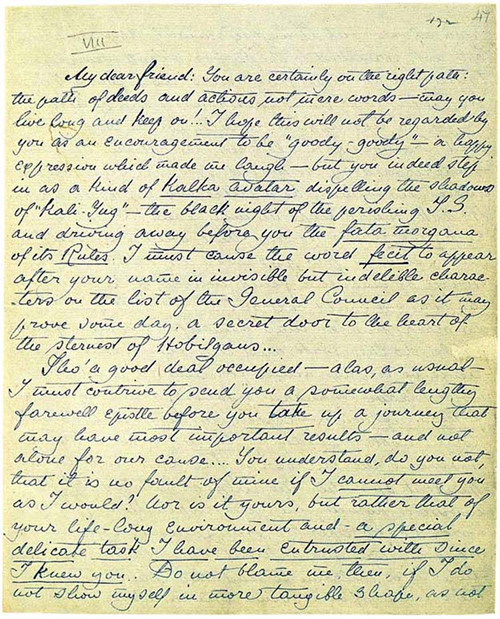

Camp, near Chapra

April 23rd 1879

My dear Mr. Rivett-Carnac,

In continuation of my last letter, dated the 20th April (& finished on the 22nd), I now proceed to notice some of the other subjects, which some of the books and papers, &c., which you sent me, bear reference to.

With regard to the Queries of Professor Schaffhausen, Nos I., II., and III, as anent Crania: There have been elongated skulls found in India, and also small crania. There are no doubt good specimens of such, for reference, in the Indian Museum, at Calcutta; and the Museum would no doubt be the best place to apply to for information on this subject.

I should say that small skulls, were of more common occurrence than elongated skulls in India. But I have never yet heard of any artificial means being used in India, either to depress, or to elongate, or otherwise to modify, the cranium!

Your quotation from the information of an officer who had been in the Punjab, is the first rumour that I ever heard of, of such a practice being followed in India. But I should think it was very doubtful! Perhaps among such a totally savage people as the Andamanese, and just barely possibly among the farthest distant and least known of the barbarous north-eastern mountaineers, on the boundary between India and China, such a practice might prevail. But, if so, we have never heard of it, -- we have no reason to suppose it, -- and we have no information to go upon. And it would be strange if we were found to be ignorant of characteristic usages among the tribes of India, while we profess to be sufficiently well informed of those of the aborigines of America! We feel pretty certain about the existence of American Indian "Flatheads"; but we are ignorant of the existence of any East-Indian tribe who could merit the application of a similar term!

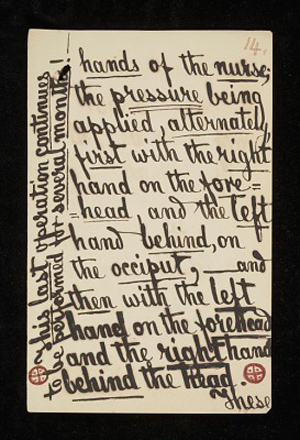

I had written thus far, when I happened to be reminded of a peculiar custom which is practiced by nearly all of the natives of India, generally; though, I believe, not exclusively by any one tribe in particular (as far as I know). I refer to the common practice, prevalent among native Indian mothers and nurses, of modifying the shape of the head of native infants, by pressure, for the sake of beauty! From the very hour in which a native infant is born, up to the eighth, tenth or twelfth day after birth, the native nurses keep the infant's head tightly bandaged round, horizontally, (that is, from the back, or occiput, to the forehead, round by the sides). And the natives say that this is intended to make the head round-shaped; or to prevent it from being long-shaped! After the bandages have been taken off; the head of the child is then, next oiled, three times every day, and pressed between the hands of the nurse; the pressure being applied, alternately, first with the right hand on the forehead and the left hand behind, on the occiput, -- and then with the left hand on the forehead and the right hand behind the head.

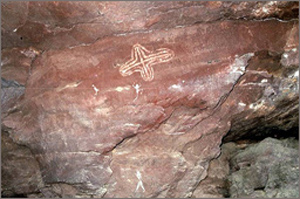

Symbol of a circle with a cross drawn through the middle, and a dot placed in the middle of each quadrant. Drawn in red ink.

This last operation continues to be performed for several months!

These various operations are not always fully and strictly carried out to the letter, in every household alike; for some natives are less particular or less observant of them, or pay less attention to them, than others, who adhere to the custom more rigidly. But the "custom", however, does not seem to be confined to any one particular caste, or class, or tribe, at all; but it appears, rather to be general!

On the whole, the entire process just described, including both the bandaging and the manipulation of the head, appears to me to be simply a very mild mode of slightly modifying the shape of the cranium, in order to suit some ideal type, of form or beauty!

The suspicion next arises, that owing to this (however slight) artificial modification of form, in human crania, in India, the consequence or result thereof may be, that most of the crania of natives of India are of an artificial or unnatural shape; or that very few crania of a natural shape can be found in India! And that consequently no criterion, whatever, can be formed, from crania, of the original, natural, or normal form or contour of the heads or skulls of the people of India, who might therefore be called "diametrio-entechno-cephalic", or "entechno-diametriocephalic" (artificially-modified-headed).

Vipassi and Patali Tree, Bharhut Stupa at the Indian Museum, Kolkata Photograph from the Indian Museum in West Bengal taken by Anandajoti.

But then, in that case, also our theoretical Indian craniological scheme or system, must be all at fault, and so vitiated as to be nearly utterly useless; because any proposed diagnosis must rest either upon doubtful characteristics, which may be of more or less artificial or semi-artificial origin, or at least, variable characteristics which can not be relied on!

Very curiously and sometimes even abnormally shaped human skulls, may occasionally be picked up along the banks of the river Ganges, that great watery cemetery of the Hindus! --

I will now give you a description of two ancient skulls which I found in Rajputana.

On the south-western borders of the Bhartpur state, on a high rocky hill, near a place called Jontpur in a sort of aboriginal grave or tomb in a crevice of the rock, I found a remarkably shaped, elongated, dolichocephalic, skull, which had apparently belonged to a young person, a boy, or a girl! --

Again, in an excavation which I made in the side of a mound, at "Nagar", near Uniyara, in Rajputana, I found a very thick, strong skull, of an adult of a very remarkable shape. This skull was of great antiquity, buried beneath the ruins of a very ancient city. This skull was not remarkable for its length, at all; but it was remarkable for the shape of its very receeding frontal bone, and for the fact that the central suture was almost entirely obliterated, by solidification!

The shape of the frontal bone was abnormal. The bones of the eyebrows projected very much and formed a raised overhanging ridge. From the brows, the frontal bone at once sloped backwards, or receeded at once, with a very great slope, so that really there was no forehead left at all! There were somewhat acute projections towards the after part of the sides of the skull, above the ear orifices, or just about where the phrenologists pretend that the organ of "caution" is situated. There was also a rather acute projection posteriorly, on the occiput. The lower jaw was gone; but the bone of the upper jaw projected very much outwards, so that the profile must have been very prognathous!

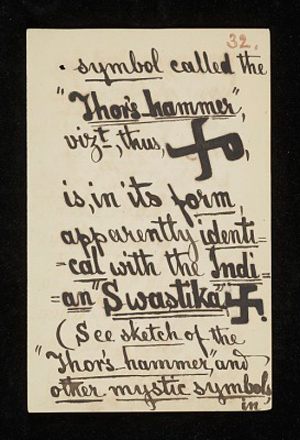

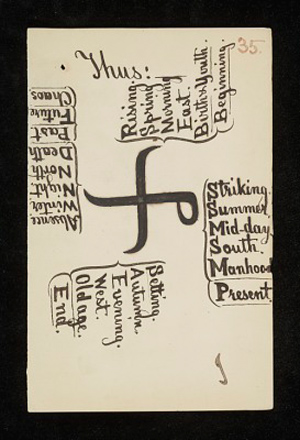

With regard to Query No "V.", about the "Thor's hammer", the Scandinavian mystical symbol called the "Thor's Hammer", vizt, thus,

is, in its form, apparently identical with the Indian Swastika

(See sketch of the "Thor's hammer" and other mystic symbols, in Baring Gould's "Iceland, its Scenes and Sagas"!)

The mystical symbol of the "Thor's hammer" really bore reference to three things (or three natural phenomena), or had a triple signification; vizt:

1. The Sun's power and course;

2. The revolution of the four seasons; and of time

3. The four quarters of the compass.

1.a. Rising, striking, setting, absence.

2.a. Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter.

2.b. Morning, mid-day, evening, night.

3.a. East, South, West, North

Thus:

Top -- Rising. Spring, Morning, East. Birth & Youth. Beginning.

Right -- Striking. Summer. Mid-day. South. Manhood, Present.

Bottom -- Setting. Autumn. Evening. West. Old Age. End.

Left -- Absence. Winter. Night. North. Death. Past. Future. Chaos.

I myself have never seen "hammers" or "axes" worshipped in India!

Round a Linga, or Mahadeo, when it happened to be situated in the open air, I have very frequently seen many naturally smoothed or rounded, stones, and oval stones, and pebbles, collected, in a crowd; and I have sometimes seen so many, that the big "Mahadeo" appeared to be standing in the midst of a forest of little ones of all shapes and sizes! But I have never yet seen any genuine "celt", or axe, in that position!

A kind of "green stone' is used as a medicine, in India. I saw it, or rather had authentic knowledge of its being so used, in Agra (as a tonic?)!

There are, however, three kinds of stones used in India, as medicine; namely:

1. A green stone, called "Dahâna Feringh", which is scraped, and the powder thus obtained, is mixed with water, and drunk, for diseases of the kidneys! This stone is probably true "Nephrite".

II. A green stone, with occasionally red and yellow marks in it (a kind of Blood-stone?), which the natives call "Pitoniya". This stone is merely dipped or washed in water; and then the water in which the stone has been dipped, is drunk as a remedy for heat or eruption of the skin; and for pimples, "prickly heat", & irritation of the skin.

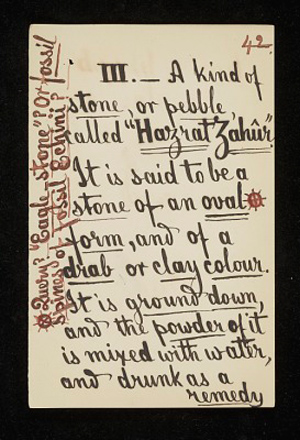

Query? "Eagle-stone"? Or fossil spines of Fossil Echini?

III. A kind of stone, or pebble, called "Hazrat Zahûr" It is said to be a stone of an oval form, and of a drab or clay colour. It is ground down and the powder of it is mixed with water, and drunk as a remedy for heat, inflammation, stricture or stoppage, in certain organs; especially for "strangury".--

I am not sure about your the correctness of your definition of "green-stone". Common "green-stone," the common "Green-stone" of geologists, is simply a kind of Trap rock; and it is not "Nephrite" !

So also "Serpentine" is quite a different mineral from the "Greenstone Trap" rock of geologists.

"Jade" I understand to be much harder stone than "Serpentine". The usual colour of "Jade", is a pretty uniform dark green. Jade "celts" have been found. -- I believe one of the names by which "Jade" is known in India, is "Zabarjad"; but this name is also applied to other minerals and precious stones such as "Beryl", and Green "Jasper", yea, -- (and also greenish "Chalcedony"!?) --

What is the meaning or signification, and what is the etymology of the word "Jade"? Does it mean a hard stone, which "jades" the person who tries to work it? Or is not the name perhaps rather derived from the Arabic word "jad", meaning good fortune, felicity, prosperity, -- and thus meaning "the lucky stone"; -- or from the Arabic word "jud", meaning munificence or beneficence, -- and thus meaning -- "the beneficial stone"? And hence, it's Perso-arabic name of "Zabar-jad", or "Zabar-jud"? (For the name is spelt both ways.) Literally meaning, -- the stone of "powerful beneficial efficacy"! --

I have now to make a few remarks about your silver coin of the Saurashtran type, and supposed by Rajendra Lall Mitra to be of "Toramana".

On account of the face, or profile, of the king's head, being turned to the left, as in another coin of Toramana, cited by Thomas (see Prinsep's Essays, Vol. 1 page 340), it would seem likely that your coin would be of Toramana, also! But as the legend, or inscription appears in the figure of the coin, as engraved in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, for December 1878, I can not read the name as "Toramana" and I regret to say that at present, I totally disagree with Rajendra Lall's reading.

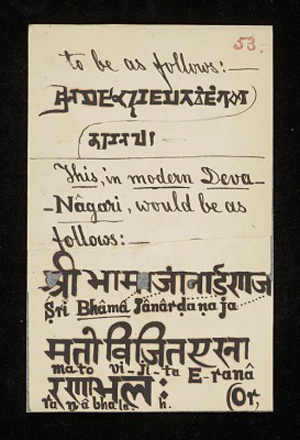

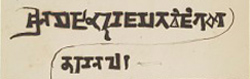

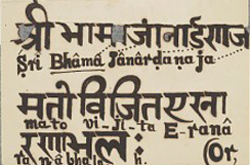

In the engraving, the letters appear to be as follows:

This, in modern Deva-Nagari, would be as follows:

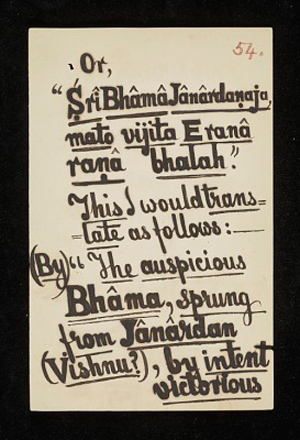

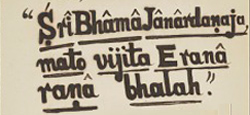

Or,

This I would translate as follows:

(By) "The auspicious Bhama, sprung from Janardan (Vishnu?), by intent victorious over Eran, in righteous battle." --

The term, "mato-vyita" if liberally translated, might mean, -- "who, by his own will", or "according to his premeditated intention, was victorious." --

But "victorious" over what, or where?

The answer is "Eranâ", -- "at", or "over", Eran"! --

And how? The answer is -- "by a just, or righteous war:" "Ranâ bhalah."

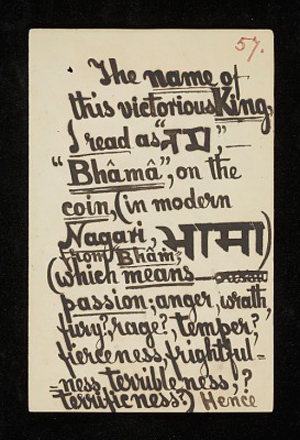

The name of this victorious King, I read as

-- "Bhama", on the coin, (in modern Nagari, from "Bham",

(which means - passion; anger, wrath, fury?, rage?, temper?, fierceness, frightfulness, terribleness,? terrificness?)

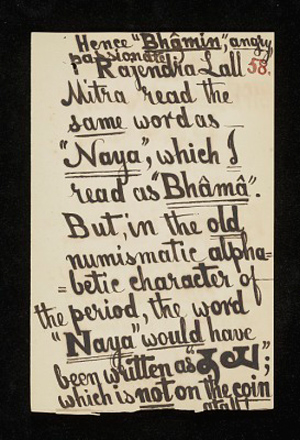

Hence "Bhamin", angry passionate:

Rajendra Lall Mitra read the same word as "Naya", which I read as "Bhama". But, in the old numismatic alphabetic character of the period, the word "Naya" would have been written as

which is not on the coin at all! --

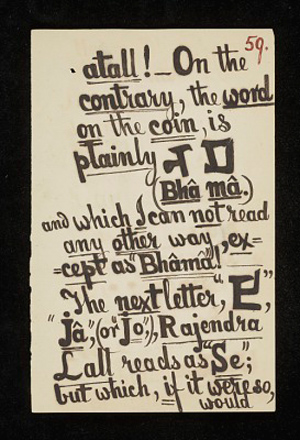

On the contrary, the word on the coin, is plainly

(Bhâ mâ) and which I can not read any other way, except as "Bhâmâ"! The next letter,

"Jâ" (or "Jo,"), Rajendra Lall reads as "Se";

but which, if it were so, would be written as

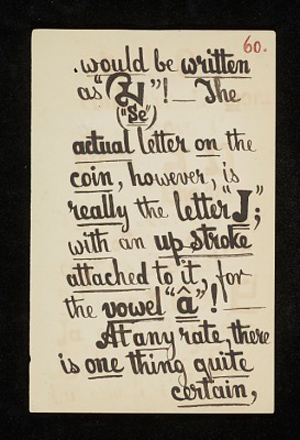

("Se")! The actual letter on the coin, however, is really the letter "J"; with an up-stroke attached to it, for a vowel "a"!

At any rate, there is one thing quite certain, and that is -- that the name of "Toramâna" does not appear upon the coin, at all; and that therefore it is not a coin of "Toramâna"!

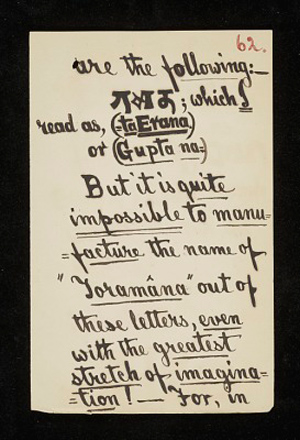

The letters on the coin, which Rajendra Lall took to form the name of "Toramâna," are the following:

which I read as, (taErana) or (Gupta na).

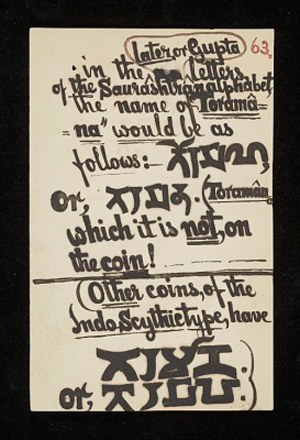

But it is quite impossible to manufacture the name of "Toramâna" out of these letters, even with the greatest stretch of imagination! For, in the later, or Gupta letters, of the Saurâshtrân alphabet, the name of "Toramâna" would be as follows:

or,

(Toramâna which it is not, on the coin!

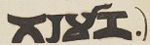

(Other coins, of the Indo Scythictype, have

or,

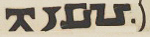

Other coins, of the Indo-Sassanian type, have simply the first part of the name, as: --

(Tora) and

Sri To ra.

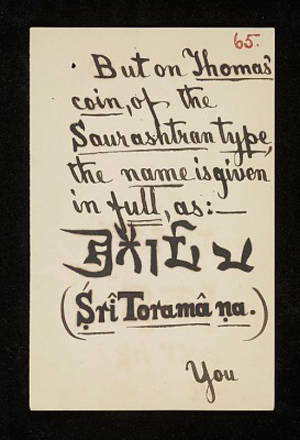

But on Thomas' coin, of the Saurashtran type, the name is given in full as:

(Srî Toramâ na.)

You will now, therefore, perceive that there is no such name on your coin!

As I before intimated, in my previous tentative reading of the inscription on your coin, I am inclined to read the name of the King as "Bhâma".

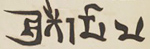

But I myself have good reason to prefer to read the name as "Bhâmâ".

("Bhâmâ".)

In some of the similar Gupta coins, of the Saurashtran type, the letter "Bh" is formed like

and

as in the titles of Kumâra Gupta on his silver coins; where Prinsep read "Bhânuvîra", and Wilson read Bhattâraka", and Thomas reads "Bhagavata"; while I read -- "Bhânudhara", on one coin and "Bhatârana", on another! (Thus do doctors differ!)

Now, if the name of the king, on your coin be "Bhâmâ"; then the next question is -- whether there was any king of that name among the later Guptas?

I think it will be found that there was! And I would place a "Bhâma Gupta", after "Buddha Gupta", and before "Vishu Gupta", say about A.D. 260 to 270, and nearly contemporary with Toramâna! (whose date is probably about A.D. 261? or 262? or 264?)

This puts me in mind that, in the month of January 1877, I received a letter from General Cunningham, in which he informed me that "two silver coins of Bhânu Gupta" had "come to light"; and that he had "an inscription of him, dated in S. 191". (of the Gupta era; = A.D. 270) I.e. S. 79 - 191 = 270

Now General Cunningham's writing of the name of the king is not distinct and I can not make out whether it is "Bhâme" (for "Bhâma") or "Bhânu"; but the date of the reign of this king, is "A.D. 270", or about contemporary with Toramâna.

I therefore think it is possible that your coin may belong to the very same king who is mentioned by General Cunningham! --

It must, however, be borne in mind that my version of the reading of the "legend" on your coin, and my interpretation of it, are merely tentative or provisional; and that my reading is founded solely and entirely upon the form, or shape, of the letters, as they appear in the figure or engraving of the coin, in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, for December 1878. My opinion is formed simply on the mechanical conformation of the letters in the legend, as shown in that drawing of the coin. But it is, of course, just possible that the drawing, or the engraving may not be true to the original or may be faulty in some of its details, (that is, if the drawing was done by a native!); and that thus, consequently, it may have given me a false or erroneous impression of the forms of the letters on the coin! But, if that be the case, it will be utterly useless and exceedingly unsafe for me to presume to express any opinion about your coin, without having ever seen, handled, or examined the piece itself! -- But if the coin be in your own possession now, perhaps I may have the privilege of examining it, when I reach Ghazipur! --

I have read through Mr Cust's book, with much interest; and I will give you my humble opinion o of its merits, with a few remarks on particular points, in my next letter.

But it is really frightfully hot now, in tents, and I suffer very much from the heat, and find it very difficult to get through much writing, or any such work. The heat addles ones brains! And "cool judgment" can hardly be expected from brains which have been stewed and roasted and grilled and scorched into a state of exhausted listlessness.

Your paper on "Cup Marks" &c. is most interesting, and excites curiosity while it certainly raises some new trains of thought in ones mind. But more of this anon!

I am very much obliged to both Mrs Rivett-Carnac and your good self, for all your kind wishes. I think I shall probably do my best to reach Ghazipur!

With best and kindest regards to Mrs. Rivett-Carnac,

Believe me,

Yours

Very sincerely

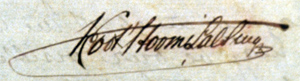

Archi C. Carlleyle

x]

x]