by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/25/23

In the course of my studies on this subject, I noticed that Church fathers like Eusebius and Lactantius, Renaissance admirers of hermetic literature like Marsilio Ficino, Jesuits like Athanasius Kircher and the figurist Joachim Bouvet, and numerous other "ancient theologians" including Chevalier Ramsay (Chapter 5) were all confronting other religions and tried to link their own religion to an "ancient" (priscus), "original," and "pure" teaching of divine origin. Reputedly extremely ancient texts such as hermetic literature, Chaldaic oracles, and the Chinese Yijing (Book of Changes) played a crucial role in establishing this link to primordial wisdom. However, I found the same endeavor also in non-Abrahamic religions such as Buddhism where neither the creator God nor Adam, Noah, or the Bible plays a role.

A good example is the Forty-Two Sections Sutra, one of the most important texts in East Asian Buddhism, which also happens to be the first Buddhist sutra translated into a European language. Though the text originated roughly 1,000 years after the birth of Buddhism [65 CE] and in China, it came to be presented as the original teaching of the Buddha (his first sermon after enlightenment) and thus also formed a link to an "original teaching." The case studies of this book show that such misdated texts -- and the urge to establish a link between one's own creed and a most ancient teaching -- played an extraordinary role in the Western discovery of Asian religions.

Many texts mentioned in our pages are concerned with some "Ur-tradition" -- God's instructions to Adam, Buddha's instructions to his closest disciples, the "original" doctrine of the Vedas revealed by Brahma, and so on. These texts are covered with the fingerprints of various reformers and missionaries. On the Forty-Two Sections Sutra I found fingerprints of an eighth-century reformist Zen master; on the Yijing those of Jesuit figurists; on the Upanishads those of Shankara and the Sufi Prince Dara; on the Ezour-vedam those of Jean Calmette and Voltaire; and on the Shastah of Bramah those of Holwell. As much as their respective agendas differ, they possess a common denominator in the obsession with vestiges of an ancient true religion that happens to support their mission. As discussed in Chapter 5, "ancient theology" thus reveals itself not as a unique European phenomenon but rather as a local form of a universal mechanism operative in the birth of religious or quasi-religious movements. This mechanism is characterized by the use of supposedly very ancient texts and unique transmission lines designed to legitimize new or reformist views by linking such views to a founder figure's old, "original" teaching....

2. The Chinese Model (Seventeenth Century)

The man who most systematically applied Japanese insights to Chinese religions, Joao Rodrigues, did extensive research on Japanese and Chinese religions and was an exceptional linguist capable of handling primary sources in both languages. He is a hitherto mostly ignored key figure whose views exerted a profound and lasting influence on European perceptions of Asian religions. Unlike Matteo Ricci, whose 1615 report about China and its religions had gained a broad readership in Europe and opened many a European's eye, Rodrigues remained in the background. His groundbreaking research on the history of Chinese religions, chronology, and geography was used by others but rarely credited to him. However, in the form of Martino Martini's publications and of documents that proved decisive in the Chinese Rites controversy, Rodrigues's ideas reached a relatively broad readership. His reports were intensively studied in missionary circles, and his distinction between esoteric and exoteric forms of Chinese and Japanese religions became widely adopted.

The two major divergent views of the China and India missions -- Ricci's and de Nobili's "good" monotheist transmission model versus Rodrigues's "evil" idolatry model -- spilled over into other realms and also had important repercussions in Rome, where Athanasius Kircher in 1667 published under the title of China Illustrata a synthesis of an enormous amount of data from the Jesuit archives and personal communication with travelers and missionaries. He thought, like Rodrigues, that the Brahmans of India were representatives of Xaca's religion who had infected the entire East with their creed. A Chinese Buddhist text helped in fostering this mistaken view: the Forty-Two Sections Sutra. Its preface explained that Buddhism was introduced to China from India in the year 65 C.E. This text played an extraordinary role not only in the European discovery of Buddhism but also in that of China, Japan, and even America (see Chapter 4)....

Couplet's Buddha

The essence of Jesuit knowledge about the religion of Foe (Ch. Fo, Buddha) in the second half of the seventeenth century is contained in the 106-page introduction of the famous Confucius Sinarum philosophus of 1687. Dedicated to King Louis XIV of France, this book -- and in particular its introduction signed (though not wholly written) by the Jesuit Philippe Couplet (1623- 93) -- played a central role in the diffusion of knowledge about Far Eastern religions among Europe's educated class and created quite a stir. A review in the Journal des Sravans of 1688 shows that it was especially Couplet's vision of the history of Chinese religions that attracted interest. The anonymous reviewer (who according to David Mungello [1989:289] was Pierre-Sylvain Regis) calculated on the basis of the chronological tables in Couplet's book that the Chinese empire had begun shortly after the deluge -- provided that one use not the habitual Vulgata chronology but the longer one of the Septuaginta (Regis 1688:105). The reviewer summarized Couplet's argument about the history of Chinese religions as follows:Following this principle, Father Couplet holds that the first Chinese received the knowledge of the true God from Noah and named him Xanti [Ch. Shangdi, supreme ruler]. One must note that the first emperors of China lived as long as the [biblical] Patriarchs and that they therefore could easily transmit this knowledge to their descendants who preserved it for 2,761 years until the reign of Mim-ti [emperor Ming] ... who through a bizarre adventure strangely altered it. (pp. 105-6)

This "bizarre adventure" was the introduction of Buddhism in China as related by Matteo Ricci, who had, with almost Voltairian guile, transformed the Forty-Two Sections Sutra's story of Emperor Ming's embassy to India in search of Buddhism into a botched quest for Christianity.17 In its course, the Chinese ambassadors supposedly stopped "on an island close to the Red Sea where the religion of Foe (this great and famous idolater of the East Indies) reigned" and ended up bringing Foe's idolatry instead of Christianity to China (p. 106). The religion of Foe or Fo was thus seen as the major cause for the loss of true monotheism in China. The role of the Jesuit missionaries, by implication, is analogous to that of Chumontou in the Ezour-vedam: it was their task to show how the true original religion of the natives had become disfigured and to prepare the ground for its restoration and perfection under the sign of the cross....

Diderot's Oriental Blend

As explained at the beginning of this chapter, Diderot's encyclopedia article on the "Bramines" (1751:2.393-94) portrays them as "priests of the god Fo" who "principally revere three things, the god Fo, his law, and the books containing their constitutions." His description of these priests combines characteristics of Fo's esoteric teaching (as reported by Japan and China missionaries) with facets of Indian religions, for example, the doctrines of emanation, cosmic illusion (maya), and ascetic quietism as described by Bernier. According to Diderot, the Brahmin priests of Fo "assert that the world is nothing but an illusion, a dream, a magic spell, and that the bodies, in order to be truly existent, have to cease existing in themselves, and to merge into nothingness, which due to its simplicity amounts to the perfection of all beings" (trans. Halbfass 1990:59-60). Thrown into the blender were also some lumps from missionary reports about Zen as well as the Forty-Two Sections Sutra (see next chapter), for example, the notion that "saintliness consists in willing nothing, thinking nothing, feeling nothing, and removing one's mind so far from any idea, even that of virtue, that the perfect quietude of the soul stays unaltered" (Diderot 1751:2.393).11 Diderot's Brahmins pretend, as in Kircher, to have sprung from the head of the god Brahma, to possess "ancient books that they call sacred," and to have preserved the ancient language of these texts (p. 393). Diderot also associates these "Brahmin priests of Fo" with some of the doctrines that form the staple of descriptions of Indian religion since Henry Lord (1630) and Abraham Roger (1651).Under Diderot's label of philosophie asiatique, the readers of the Encyclopedie thus found a blend of "Asian" teachings and practices that were all associated with Brahmins who propagated the religion of Fo....

The Forty-Two Sections Sutra

De Guignes had a kind of Bible for all things Chinese. Whether he was writing about Chinese history or religion, on virtually every page he either refers to or quotes from the Wenxian tongkao (Comprehensive examination of literature) compiled by MA Duanlin (1245-1322). Published after twenty years of work in 1321, this masterpiece of Chinese historiography soon became indispensable because it provided thematically arranged extracts from a very wide range of other Chinese works. Students preparing for China's civil service examinations sometimes memorized Ma's chapter introductions, and missionaries and early Western Sinologists appreciated the giant work because it furnished so much (and so judiciously selected) textual material from original sources.One can say that this excellent work is by itself equivalent to an entire library and that even if Chinese literature would only consist of this work it would be worth the trouble to learn Chinese just to read this. It is not only about China that one would learn much but also a large part of Asia, and regarding everything that is most important and noteworthy about its religions, legislation, rural economics and politics, commerce, agriculture, natural history, history, physical geography, and ethnography. One only has to choose the subject which one wants to study and then to translate what Ma Duanlin has to say about it. All the facts are reported and classified, all sources indicated, and all authorities cited and discussed. (Abel-Remusat 1829:2.170)

This was the work that men like de Visdelou and de Guignes always seemed to have at hand; and some China missionaries only appeared to be so well read because they failed to mention that Ma Duanlin was the source of their quotations from so many Chinese works (p. 171). It was in the Wenxian tongkao that de Guignes found much of the material for his History of the Huns, and the influence of this collection was so great that Abel-Remusat stated in 1829 that Ma Duanlin alone was at the origin "of the large part of positive knowledge that one has so far acquired in Europe about Chinese antiquity" (p. 171-72). While this may be a bit exaggerated in view of the translations of Chinese classics and histories of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there is no doubt that for de Guignes this collection was of supreme importance. For example, fascicles 226 and 227 of Ma Duanlin's work, which deal with Buddhism and its literature, are the source of much of the solid information (as opposed to speculation) that de Guignes conveyed about this topic to his pan-European readership.

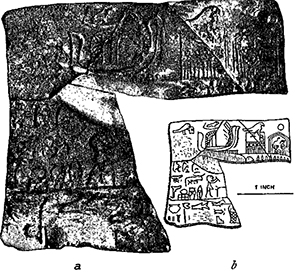

In the introduction to his Buddhism sections, Ma Duanlin recounts the traditional story about the dream of Emperor Ming of the Han dynasty (re. 58-75 CE.) and the introduction of Buddhism to China. The emperor saw a spirit flying in his palace courtyard, was told that this had to do with an Indian sage called Buddha, and sent an embassy to India. Accompanied by two Indian monks, this embassy brought the Forty-Two Sections Sutra and a statue of the Buddha on a white horse back to China in 65 CE. The famous White Horse Monastery (Baimasi) was built near the capital Chang'an (today's Xian) in order to store this precious text and China's first Buddha statue.

This is the story de Guignes was familiar with. But the more modern Sinologists led by Maspero (1910) learned about it, the more this Story turned out to be a classic foundation myth. Today we know that there is no evidence that such an embassy ever took place; that the oldest extant Story of Emperor Ming's dream had a man as leader of the ambassadors who had lived two hundred years earlier; that Buddhism was introduced to China before the first century of the common era; that the first references to a White Horse Monastery date from the third century CE.;16 and of course, as is the rule with such myths, that striking details -- such as the first Buddha image and the two Indian monks accompanying the white horse -- enter the game suspiciously late (here in the fifth century).

While this tale of the introduction of Buddhism to China is today regarded as a legend without any historical basis, the Forty-Two Sections Sutra itself has a reasonable claim to antiquity. It is an exaggeration to say that "most scholars believe that the original Scripture of Forty-Two Sections, whatever its origins, was indeed in circulation during the earliest period of Buddhism in China" (Sharf 2002:418). One can only state with confidence that some of its maxims and sayings are documented from the second century onward and that some of the vocabulary of the text indicates (or wants to indicate) an origin in the first centuries CE. The scholarly consensus in Japan holds that the text as we know it stems not from the first or second century but is a Chinese compilation dating from the fifth century CE. that combined passages and sayings from a number of different Buddhist texts (Okabe 1967).

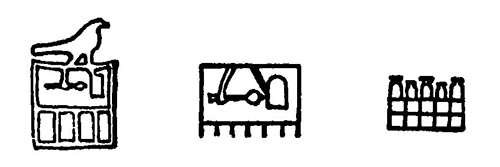

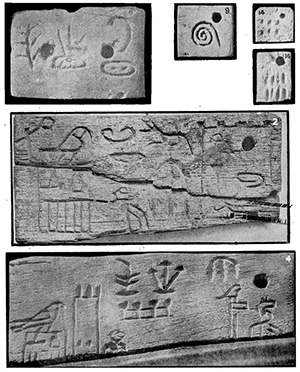

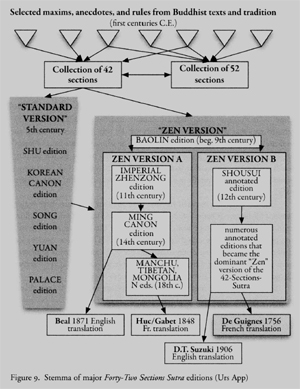

Twentieth-century research has also revealed that there are three major versions of this text (Okabe 1967). The first, included in the Korean Buddhist canon, appears to more or less closely reproduce the original fifth-century compilation and is here called "standard version." The version used by de Guignes, by contrast, first emerged around 800 CE. and contains some sections that are strikingly different from the standard version. Figure 9 shows the genealogy of editions of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra.

Figure 9. Stemma of major Forty-Two Sections Sutra editions (Urs App)

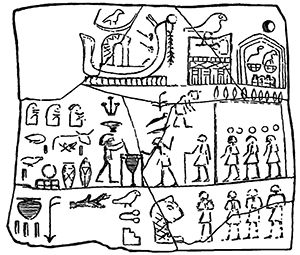

Since exactly these modified sections (Yanagida 1955) are of central importance for de Guignes's interpretation of "Indian religion," a bit more information is needed here. The book entitled Baolin zhuan ("Treasure Forest Biographies") of 801 -- which was the first text to include the modified Forty-Two Sections Sutra -- is known as a scripture of the Chan or Zen tradition of Chinese Buddhism. Rather than a separate "sect" in the ordinary sense, this was a typical reform movement involving Buddhist monks of a variety of different affiliations who had a particular interest in meditation17 and wanted to link their reform to the founder's "original teaching." For this purpose, lineages of transmission were created out of whole cloth, and soon enough the founder Buddha was linked to his eighth-century Chinese "successors" by a direct line of Indian patriarchs at whose end stood Bodhidharma, the legendary figure who fulfills the role of transmitter and bridge between India and China. Needless to say, all this was a pious invention to legitimize and anchor the reform movement in the founder's "original" teaching that supposedly was transmitted "mind to mind" by an unbroken succession of enlightened teachers reaching back to the Buddha. According to this very creative Story line, the Buddha once showed a flower to his assembly and only one member, his disciple Mahakashyapa, smiled. He thus became the first Indian "Zen" patriarch who had received the Buddha's formless transmission. Such transmission lineages had much evolved since their modest beginnings in genealogies of Buddhist masters of Kashmir and in Tiantai Buddhist lore. In the eighth century, Zen sympathizers tested a number of variants until, in the year 801, a model emerged that carried the day (Yampolsky 1967:47-50). This was the model of the Baolin zhuan featuring twenty-seven Indian patriarchs and the twenty-eighth patriarch Bodhidharma, the legendary founder of Zen whom Engelbert Kaempfer had depicted crossing the sea to China on a reed (see Figure 10 below).

The partially extant first chapter of this "Treasure Forest" text presented the biography of the founder, Shakyamuni Buddha, and this chapter contained the modified text of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra. The setting is, of course, significant: the sutra is uttered just after the Buddha's enlightenment and thus constitutes the founder's crucial first teaching. This alone was quite a daring innovation that turned a collection of maxims, anecdotes, and rules into a founder's oration. But the ninth-century editor of the Baolin zhuan went one significant step further. Not content faithfully to quote the conventional text of the sutra, he changed various sections and added passages that clearly reflected his own reformist "Zen" agenda. This method of putting words into the founder's mouth was and is, of course, popular in many religions; but in this case it was a particularly effective ploy. Not only did the Buddha now utter things that furthered the editor's sectarian agenda-and turned the text into a "sutra" -- but he said these things in his very first speech after enlightenment! And this speech formed a text that was not just any text but the reputedly first and oldest text of Buddhism and for good measure also the first one to make its way to China and to be translated into Chinese! What better pedigree and vehicle for reformist teachings could one wish for?

The Zen movement as a whole was crowned with brilliant success, as Ma Duanlin's list of Buddhist literature in fascicle 227 of his work shows: more than one-third of the eighty-three listed texts are products of the Zen tradition (for example, the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, Blue Cliff Record, and Records of Linji). The "Zen-ified" text of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra, too, was a smashing success. It became by far the most popular version of this sutra, was printed and reprinted with various commentaries, and in the Song period was even included as the first of the "three classics" (Ch. sanjing) of Buddhism.18 A copy of it found its way into the Royal Library in Paris, and this is the text de Guignes set out to translate in the early 1750S.19 It is worthy of note that it was exactly the most "Zen-ified" version of this text that served to introduce Europe to Buddhist sutras, that is, sermons purportedly uttered by the Buddha.20

The difference between the three major versions of the Forty- Two Sections Sutra is of great interest as it exhibits the motives of their respective editors. For example, the end of section nine of the standard version reads as follows:Feeding one billion saints is not as good as feeding one solitary buddha (pratyekabudda). Feeding ten billion solitary buddhas is not as good as liberating one's parents in this life by means of the teaching of the three honored ones. To teach one hundred billion parents is not as good as feeding one buddha, studying with the desire to attain buddhahood, and aspiring to liberate all beings. But the merit of feeding a good man is [still] very great. It is better for a common man to be filial to his parents than for him to serve the spirits of Heaven and Earth, for one's parents are the supreme spirits. (Sharf 2002:424)

Whether one regards the portions of the text that are here emphasized by bold type as interpolations or not, their emphasis on filial piety clearly exhibits the Chinese character of this text and fits into the political climate of fifth-century China. The Imperial Zhenzong edition (Zen version A), which adopted a number of the "Zen" changes from the Baolin zhuan, leaves out part of the first phrase but also praises filial piety:Feeding one billion saints is not as good as feeding one solitary buddha (pratyekabudda). Feeding ten billion solitary buddhas is not as good as feeding one buddha, studying with the desire to attain buddhahood, and aspiring to liberate all beings. But the merit of feeding a good man is [still] very great. It is better for a common man to be filial to his parents than for him to serve the spirits of Heaven and Earth, for one's parents are closest.

For a religion whose clergy must "leave home" (ch. chujia) and effectively abandon parents and relatives in order to join the family of the monastic sangha, this call for filial piety may seem a little odd; but this kind of passage certainly helped fend off Confucian criticism about Buddhism's lack of filial piety. Compared to the standard edition, the "imperial" edition (Zen version A) effectively sidelined the issue and made it clear that "feeding one buddha, studying with the desire to attain buddhahood, and aspiring to liberate all beings" is the highest goal. The Shousui text (Zen version B), by contrast, mentions not one word about filial piety and advocates a rather different ideal:Feeding one billion saints is not as good as feeding one solitary buddha (pratyekabudda). Feeding ten billion solitary buddhas is not as good as feeding one of the buddhas of the three time periods. And feeding one hundred billion buddhas of the three time periods is not as good as feeding someone who is without thought and without attachment, and has nothing to attain or prove.

This goal reflects the agenda of the Zen sympathizer who edited the Forty-Two Sections Sutra around the turn of the ninth century and decided to put this novel teaching straight into the mouth of the newly enlightened Buddha. De Guignes, who used a "Zen version B" text, translated the part emphasized by bold type quite differently from my rendering above:One billion O-lo-han are inferior to someone who is in the degree of Pie-tchi-fo, and ten billion Pietchi-fo inferior to someone who has reached the degree of San-chi-tchu-fo. Finally, one hundred billion Sanchi- tchu-fo are not comparable to one who no more thinks, who does nothing, and who is in a complete insensibility of all things. (de Guignes 1759:1.2.229)

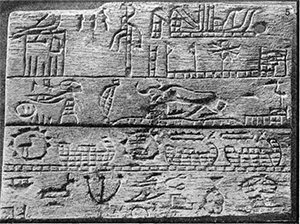

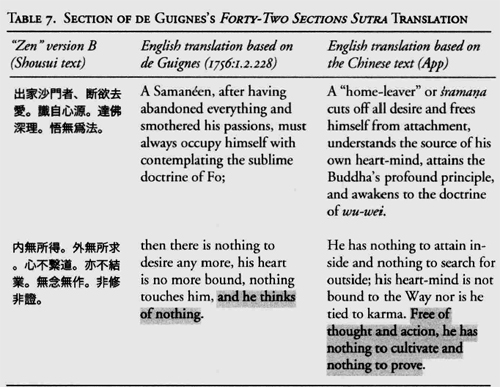

This last passage played a crucial role in de Guignes's definition of the Samaneens and their ideal. He interpreted the different stages of perfection as stages of rebirth and purification. This conception lies at the heart of his view that the ideal Samaneens, who in the Zen version B text are credited with exactly such absence of discriminating thought and attachment, represent the ultimate stage of transmigration before union with the Supreme Being. Theirs is the "religion of annihilation" (la religion de l'aneantissemen) de Guignes found at the very beginning of the Sutra text where the Buddha says, "He who abandons his father, his mother, and all his relatives in order to occupy himself with the knowledge of himself and to embrace the religion of annihilation is called Samaneen" (de Guignes 1759:1B.227) The corresponding standard text defines the Samaneens as follows: "The Buddha said: Those who leave their families and their homes to practice the way are called sramanas." The Zen text version A and also version B used by de Guignes, by contrast, have: "The Buddha said: A home-leaver or sramana cuts off all desire and frees himself from attachment, understands the source of his own mind, attains the Buddha's profound principle, and awakens to the doctrine of wu-wei." This "doctrine of wu-wei" (literally, "nonaction") was interpreted by de Guignes as "religion of annihilation."21 It was thus exactly the eight-character-phrase [x] ("know the mind / reach the source / understand the doctrine of wu-wei") that the Zen editor had slipped into the opening passage that inspired de Guignes to define the religion of the Samaneens as a "religion of annihilation." He found this ideal confirmed in other passages of his Forty-Two Sections Sutra. The second section, which is also exclusive to the Zen versions, is shown in Table 7.

TABLE 7. SECTION OF DE GUiGNES'S FORTY-TWO SECTIONS SUTRA TRANSLATION

"Zen" version B (Shousui text) / English translation based on de Guignes (1756:I.2.228) / English translation based on the Chinese text (App)

[x] / A Samaneen, after having abandoned everything and smothered his passions, must always occupy himself with contemplating the sublime doctrine of Fo; / A "home-leaver" or sramana cuts off all desire and frees himself from attachment, understands the source of his own heart-mind, attains the Buddha's profound principle, and awakens to the doctrine of wu-wei.

[x] / then there is nothing to desire any more, his heart is no more bound, nothing touches him, and he thinks of nothing. / He has nothing to attain inside and nothing to search for outside; his heart-mind is not bound to the Way nor is he tied to karma. Free of thought and action, he has nothing to cultivate and nothing to prove.

De Guignes's translation in places reads more like a paraphrase; some phrases are left untranslated, and there is a very understandable ignorance of technical terminology. For example, de Guignes translates the text's "nor is he tied to karma" as "nothing touches him." The lack of specialized dictionaries and a tenuous grasp of classical Chinese grammar must have made translation not just a tedious but also a hazardous enterprise. So much more astonishing is the degree of confidence that de Guignes seemed to have in his skill as a translator and interpreter of Chinese texts.

The God of the Samaneens

An anonymous British reviewer once described de Guignes as a man who is "almost always wading through the clouds of philology, to snuff up conjectures."22 He must have been thinking of de Guignes's theories about the Egyptian origin of the Chinese people or his conviction, built on a flimsy legend in Ma Duanlin's work, that Chinese Buddhist missionaries had discovered America in the fifth century C.E. (de Guignes 1761). But de Guignes's tendency to take some ambiguous drop of information and to wring earth-shattering torrents of conclusions from it is already in evidence in his very first translation from the Forty-Two Sections Sutra. His interpretation of the first word of the sutra's preface, as it happens, was just such a "cloud of philology," and the house of cards de Guignes built on this one-legged stool was of a truly astonishing scale. This was de Guignes's first attempt to come to terms with the content and history of the creed that he called "Indian religion" and to introduce the central and oldest text by this religion's founder, so it is no surprise that many readers and other authors were inspired.23 De Guignes's mistranslation and misinterpretation of the first word of this preface thus not only set his own interpretation of Buddhism on the wrong footing but misled a generation of readers unable to read Chinese who naturally relied on de Guignes's "expertise."

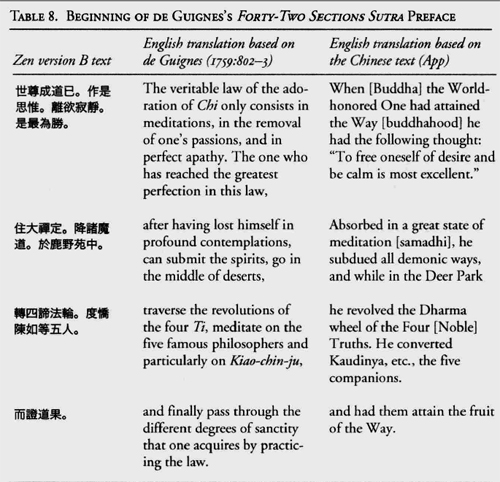

Zen version B's short preface appears to have been authored by the editor of the Baolin zhuan around the turn of the ninth century. Since that editor wanted to portray the Forty-Two Sections Sutra -- which he had so cleverly used as a host for his reformist "Zen" agenda -- as the first sermon of the Buddha after his enlightenment, his "Zen Version B" text, of course, situated the action at the Deer Park in Saranath where the Buddha first taught (turned the dharma wheel of the Four Noble Truths); see Table 8.

TABLE 8. BEGINNING OF DE GUIGNES'S FORTY-TWO SECTIONS SUTRA PREFACE

Zen version B text / English tramslation based on de Guignes (1759:802-3) / English translation based on the Chinese text (App)

[x] / The veritable law of the adoration of Chi only consists in meditations, in the removal of one's passions, and in perfect apathy. The one who has reached the greatest perfection in this law, / When [Buddha] the World-honored One had attained the Way [buddhahood] he had the following thought: "To free oneself of desire and be calm is most excellent."

[x] / after having lost himself in profound contemplations, can submit the spirits, go in the middle of deserts, / Absorbed in a great state of meditation [samadhi], he subdued all demonic ways, and while in the Deer Park

[x] / traverse the revolutions of the four Ti, meditate on the five famous philosophers and particularly on Kiao-chin-ju, / he revolved the Dharma wheel of the Four [Noble] Truths. He converted Kaudinya, etc., the five companions.

[x] / and finally pass through the different degrees of sanctity that one acquires by practicing the law. / and had them attain the fruit of the Way.

De Guignes's translation of this preface makes one doubt his grasp of classical Chinese and confirms that he would hardly have been in a position to produce the translations in his History of the Huns without the constant help of de Visdelou's manuscripts. But translating such texts in mid-eighteenth-century Paris was an extremely difficult undertaking. Some reading of Buddhist texts would have quickly showed that "the world-honored one" is a very common epithet of the Buddha. But there were few such texts at hand, and the Chinese character dictionaries of the Royal Library (Leung 2002:196-97) as a rule did not list compounds. Still, the "subject-verb-past particle" structure should have suggested something like "XX having attained the Way ... " rather than de Guignes's wayward "the veritable law of the adoration of Chi only consists in ... " For de Guignes everything turned around this "adoration of Chi." In his view this "veritable law" consisted in "meditations, removal of one's passions, and in perfect apathy." Furthermore, de Guignes thought that this preface outlined a process through which those who practice this law "pass through the different degrees of sanctity" before reaching the greatest perfection, and used this as textual support for his conception of the Samaneens as the ultimate stage of the transmigration process. But ultimately de Guignes's interpretation hinged on the meaning of the first two characters that he translated as "adoration of Chi." The first character chi (which today is romanized as shi) usually means "century" or "world." But here it forms part of the compound shizun, which in Chinese Buddhist texts is one of the most common appellations of the Buddha. It literally means "the world-honored one" and is as common in Buddhist texts as in Christian texts the phrase "our savior" that, as everyone knows, refers to Jesus. Probably due to lack of exposure to Buddhist texts, de Guignes did not realize this and explained the meaning of the first character chi or shi as follows:Chi, in the Chinese language, means century and corresponds to the Arabic word Alam, which the translator of the Anbertkend employed in the same sense; it is thus the adoration of the century that is prescribed in both works. What Masoudi reports of the Hazarouan-el-alam, a duration of 36,000 years (or according to others 60,000 years) was adopted by the Brahmins and is the same as this Chi of the Chinese. This Hazarouan possessed the power over things and governed them all. In the Indian system, the Chi or Hazarouan corresponds perfectly to this Eon of the Valentinians who pretend that the perfect Eon resides in eternity in the highest heaven that can neither be seen nor named. They called it the first principle, the first father. (de Guignes 1759:803)

In support of this view, de Guignes here referred to the famous two-volume Critical History of Mani and Manichaeism (1734/1739) by Isaac de BEAUSOBRE (1659-1738). Citing St. Irenaeus, Beausobre had characterized this Eon of the Valentinians as "invisible, incomprehensible, eternal, and alone existing through itself" and as "God the Father" who is also called "First Father, First Principle, and Profundity" (Beausobre 1984:578). Following Beausobre, de Guignes stated that these Christian heretics "admitted a perfect Eon, the Eon of Eons," and concluded without further ado that exactly this Eon of Eons "is the Chi of the Samaneens" (de Guignes 1759:804). For de Guignes and his readers this appeared to be solid textual evidence in support of a monotheistic interpretation of esoteric Buddhism, an interpretation that some had already encountered in Brucker (1742-44:48.821-22) or Freret (1753; see Chapter 7).

De Guignes's 1753 paper on the Samaneens thus ended with a monotheistic bang. Three years later, in the History of the Huns, he spelled out some of the implications. After having once more laid out his view of the exoteric and esoteric followers of Fo and described the Samaneen as a person who "is free of all these passions, exempt of all impurity, and dies only to rejoin the unique divinity of which his soul was a detached part" (de Guignes 1756:1.2.225), de Guignes explains the Samaneen vision of God in a manner that echoes Brucker:This supreme Being is the principle of all things, he is from all eternity, invisible incomprehensible, almighty, sovereignly wise, good, just, merciful, and self-originated. He cannot be represented by any image; one cannot worship him because he is beyond any adoration, but one can depict his attributes and worship them. This is the beginning of the idolatric cult of the peoples of India. The Samaneen who is ever occupied with meditation on this great God, only seeks to annihilate himself in order to rejoin and lose himself in the bosom of the Divinity who has pulled all things out of nothing and is itself different from matter. This is the meaning that they give to emptiness and nothingness. (de Guignes 1756:1.2.226)

For de Guignes this sovereign Being, this "great God," is the one who in the "doctrine of the Samaneens or Philosophers has the Chinese name of Chi" (p. 226). This fact forms the core of de Guignes's conception of the real (monotheist) religion of Buddha. He even read a creator God into the last section of his 1756 translation of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra. That section contains a passage that compares the Buddha's "method of skilful means" (Ch. fangbianmen) to a magician's trick ([x]). Like a magician in his own right, de Guignes pulled nothing less than the creatio ex nihilo out of this simple phrase. He translated it by "the creation of the universe that has been pulled from nothingness [I regard as] just the simple transformation of one thing into another" (p. 233).

After his translation of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra, de Guignes summarized his view of it as follows:I thought I had to report here the major part of this work that forms the basis of the entire religion of the Samaneens. Those who glance at it will only find a Christianity of the kind that the Christian heresiarchs of the first century taught after having mixed ideas from Pythagoras on metempsychosis with some other principles drawn from India. This book could be one of those false gospels that were current at the time. With the exception of a few particular ideas, all the precepts that Fo conveys seem to be drawn from the gospel. (pp. 233-34)

De Guignes's misunderstanding and mistranslation not only confirmed his fixed idea of the monotheism of the Samaneens but also led to an entirely original assessment of the history of their religion. Without making any attempt to help his confused readers, de Guignes suggested that the purportedly oldest book of this religion was an apocryphal Christian gospel of gnostic tendency from the early first century C.E. In a paper read in the fall of 1753 he also argued -- possibly inspired by de Visdelou's annotated translation of the Nestorian stele that repeatedly made the same point -- that the Chinese had mixed up Nestorian Christians with Buddhists.24 Not content with this narrow argument based on the text of the stele, he grew convinced that the Chinese mixup of Christianity with Foism happened on such a scale that they even "gave Jesus Christ the name of Fo!' (de Guignes 1764:810). In a sense, his theory about the Forty-Two Sections Sutra was a counterpart to the story line advanced by Ruggieri (Rule 1986:10) and Ricci that proposed that Emperor Ming's dream about a saint from the West had been about Jesus Christ and that the imperial embassy had mistakenly brought back the idolatry of Fo instead of the truth of Christianity. According to de Guignes, however, the Chinese ambassadors had imported a heretical kind of Christianity and fallen victim to the delusion that it was the religion of Fo.

But what about the origin of the religion of Fo around 1000 B.C.E. that de Guignes had found documented in so many Chinese and Arabic sources? Did he now believe that its exoteric and esoteric teachings were all from the common era? Where did Pythagoras learn about metempsychosis? What were those "other principles" from (presumably pre-Christian-era) India that were supposedly mixed in? Do the Vedas belong to this religion or are they older? In the 1750s de Guignes left these and many other questions unanswered; and when he revisited the theme two decades later, the Christian heresiarchs and the view of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra as an apocryphal gospel had vanished like a magician's doves and rabbits.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

The Sutra of Forty-two Chapters (also called the Sutra of Forty-two Sections, Chinese: 四十二章經) is often regarded as the first Indian Buddhist sutra translated into Chinese. However, this collection of aphorisms may have appeared some time after the first attested translations, and may even have been compiled in Central Asia or China.[1] According to tradition, it was translated by two Yuezhi monks, Kasyapa Matanga (迦葉摩騰) and Dharmaratna (竺法蘭), in 67 CE. Because of its association with the entrance of Buddhism to China, it is accorded a very significant status in East Asia.[2]

Story of translation

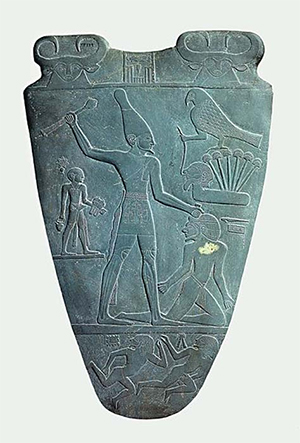

In the Annals of the Later Han and the Mouzi lihuo lun, Emperor Ming of Han (r. 58-75 C.E.) was said to have dreamed of a spirit, who had a "gold body" and a head which emitted "rays of light".[3] His advisers identified the spirit as Buddha, who was supposed to have the power of flight.[4] The emperor then ordered a delegation (led by Zhang Qian [5]) to go west looking for the Buddha's teachings. The envoys returned, bringing with them the two Indian monks Kasyapa Matanga and Dharmaratna, and brought them back to China along with the sutra. When they reached the Chinese capital of Luoyang, the emperor had the White Horse Temple built for them.[6]

They are said to have translated six texts, the Sutra of Dharmic-Sea Repertory (法海藏經), Sutra of the Buddha's Deeds in His Reincarnations (佛本行經), Sutra of Terminating Knots in the Ten Holy Terras (十地斷結經), Sutra of the Buddha's Reincarnated Manifestations (佛本生經), Compilation of the Divergent Versions of the Two Hundred and Sixty Precepts (二百六十戒合異), and the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters. Only the last one has survived.[7]

Scholars, however, question the date and authenticity of the story. First, there is evidence that Buddhism was introduced into China prior to the date of 67 given for Emperor Ming's vision. Nor can the sutra be reliably dated to the first century. In 166 C.E., in a memorial to Emperor Huan, the official Xiang Kai referred to this scripture multiple times. For example, Xiang Kai claims that, "The Buddha did not pass three nights under the [same] mulberry tree; he did not wish to remain there long," which is a reference to Section 2 of the scripture. Furthermore, he also refers to Section 24 of the scripture, when Xiang Kai tells the story of a deity presenting a beautiful maiden to the Buddha, to which the Buddha replies that "This is nothing but a leather sack filled with blood."[8] Nonetheless, while these sections seem to mirror the extant edition of the text, it is possible that the edition we now have differs substantially from the version of the text circulating in the second century.

Structure and comparison with other works

The Sutra of Forty-two Chapters consists of a brief prologue and 42 short chapters (mostly under 100 Chinese characters), composed largely of quotations from the Buddha. Most chapters begin "The Buddha said..." (佛言...), but several provide the context of a situation or a question asked of the Buddha. The scripture itself is not considered a formal sutra, and early scriptures refer to the work as "Forty-two Sections from Buddhist Scriptures" or "The Forty-two Sections of Emperor Xiao Ming."[9]

It is unclear whether the scripture existed in Sanskrit in this form, or was a compilation of a series of passages extracted from other canonical works in the manner of the Analects of Confucius. This latter hypothesis also explains the similarity of the repeated "The Buddha said..." and "The Master said," familiar from Confucian texts, and may have been the most natural inclination of the Buddhist translators in the Confucian environment, and more likely to be accepted than a lengthy treatise.[10] Among those who consider it based on a corresponding Sanskrit work, it is considered to be older than other Mahayana Sutras, because of its simplicity of style and naturalness of method.[11] Scholars have also been able to find the aphorisms present in this scripture in various other Buddhist works such as Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta, Anguttara Nikayas, and Mahavagga. Furthermore, scholars are also uncertain if the work was first compiled in India, Central Asia, or China.[12]

In fiction

Main article: The Deer and the Cauldron

In Jin Yong's novel The Deer and the Cauldron, the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters is the key to the Manchu's treasures. The Shunzhi Emperor, who is unwilling to let out the secret, spread rumours about it being the source of life of the invading Manchus. The protagonist, Wei Xiaobao, manages to get hold of all the eight books at the end of the novel.

In modern Buddhism

The Sutra in Forty-two Chapters is well known in East Asian Buddhism today. It has also played a role in the spread of Buddhism to the West. Shaku Soen (1859-1919), the first Japanese Zen master to teach in the West, gave a series of lectures based on this sutra in a tour of America in 1905-6. John Blofeld, included a translation of this scripture in a series begun in 1947.[13]

Notes

1. Sharf 1996, p.360

2. Kuan, 12.

3. Sharf 1996, p.360

4. Sharf 1996, p.360

5. Sharf 1996, p.360

6. Sharf 1996, p.361

7. Kuan, 19-24.

8. Sharf 1996, p.361

9. Sharf 1996, p.361-362

10. Soyen Shaku. "The Sutra of Forty Chapters". Zen for Americans. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

11. Beal, S. (1862). "The Sutra of Forty-two Sections". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 19, 337-349. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

12. Sharf 1996, p.362

13. Sharf 1996, p.362.

References

• Sharf, Robert H. "The Scripture in Forty-two Sections" Religions of China In Practice Ed. Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Princeton: Princeton University Press,1996. 360-364. Print.

• Cheng Kuan, tr. and annotater. The Sutra of Forty-two Chapters Divulged by the Buddha: An Annotated Edition. Taipei and Howell, MI: Vairocana Publishing Co., 2005.

• Urs App:

o "Schopenhauers Begegnung mit dem Buddhismus." [Schopenhauer and Buddhism, by Peter Abelsen] (PDF, 1.56 Mb, 28 p.) Schopenhauer-Jahrbuch 79 (1998), pp. 35-58.

o Arthur Schopenhauer and China. Sino-Platonic Papers Nr. 200 (April 2010) (PDF, 8.7 Mb, 164 p.) (This book contains a chart with the textual history of The Sutra of Forty-two Chapters, discusses its first translation into a European language by de Guignes, traces Western translations such as those by de Guignes, Huc, D. T. Suzuki, and Schiefner to specific text versions, and discusses the sutra's early influence on Schopenhauer).

Text of the Sutra

Translations

English

• Shaku, Soyen: Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro, trans. (1906). The Sutra of Forty-two Chapters, in: Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot, Zen For Americans, Chicago, The Open Court Publishing Company, pp. 3-24

• Matanga, Kasyapa, Ch'an, Chu, Blofeld, John (1977). The Sutra of Forty-Two Sections, Singapur: Nanyang Buddhist Culture Service. OCLC

• The Buddhist Text Translation Society (1974). The Sutra in Forty-two Sections Spoken by the Buddha. Lectures by the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua given at Gold Mountain Monastery, San Francisco, California, in 1974. (Translation with commentaries)

• Beal, Samuel, trans. (1862). The Sutra of the Forty-two Sections, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 19, 337-348.

• Chung Tai Translation Committee (2009), The Sutra of Forty-Two Chapters, Sunnyvale, CA

• Sharf, Robert H. (1996). "The Scripture in Forty-two Sections". In: Religions of China In Practice Ed. Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 360-364

• Heng-ching Shih (transl.), The Sutra of Forty-two Sections, in: Apocryphal Scriptures, Berkeley, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 2005, pp 31-42. ISBN 1-886439-29-X

• Matsuyama, Matsutaro, trans. (1892): The Sutra of forty-two sections and other two short Sutras, transl. from the Chinese originals, Kyoto: The Buddhist Propagation Society

German

• Karl Bernhard Seidenstücker (1928). Die 42 Analekta des Buddha; in: Zeitschrift für Buddhismus, Jg. 1 (1913/14), pp. 11–22; München: revised edition: Schloß-Verlag. (based on D.T. Suzuki's translation)

Latin

• Alexander Ricius, Orsa Quadraginta duorum capitum

was mani or Mannus, the progenitor of humanity, which once more forms a special section in the

was mani or Mannus, the progenitor of humanity, which once more forms a special section in the  for Mannus or Mene, the spiritual Moon (Psychomena).

for Mannus or Mene, the spiritual Moon (Psychomena). is Tyr, Zio, also Zeizzo or Erich, the one-armed sword-god, the "generator." His hieroglyph also consists of the sign of Ur

is Tyr, Zio, also Zeizzo or Erich, the one-armed sword-god, the "generator." His hieroglyph also consists of the sign of Ur  and the Tyr-rune

and the Tyr-rune  , which symbolizes the solar ray, the solar arrow as impregnator (phallus). His sword, his one-arm, his phallus erectus, clearly designates him as the provider of increase, the multiplier or generator under whose guardianship marriages stood, but war as well, since war increased property through the taking of booty and drove out vermin. The fourth, Mercury

, which symbolizes the solar ray, the solar arrow as impregnator (phallus). His sword, his one-arm, his phallus erectus, clearly designates him as the provider of increase, the multiplier or generator under whose guardianship marriages stood, but war as well, since war increased property through the taking of booty and drove out vermin. The fourth, Mercury  , is Wuotan, whose rune (othil

, is Wuotan, whose rune (othil  ) is in this instance reversed

) is in this instance reversed  and connected to the sign of increase

and connected to the sign of increase  to form

to form  , indicating the increaser, bringer of luck, the wish-god.

, indicating the increaser, bringer of luck, the wish-god.  , and means primeval generation, or "the one who generates things out of the Ur"

, and means primeval generation, or "the one who generates things out of the Ur"