by Theosophy Wiki

Accessed: 3/20/21

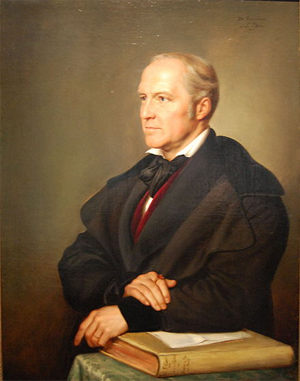

Nishikânta Chattopâdhyâya (1852-1910) was a well-known Hindu gentleman, Principal of the Hyderabad College and author of works on Oriental, Theosophical, philosophical, and other subjects. His name was erroneously thought to have been a pseudonym used by Master K.H. in Europe.

Personal life and education

Little is known of the life of Nishikânta Chattopâdhyâya. He was educated in Europe:

Mr. Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya has taken the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) at the University of Zurich. The Dean of the Faculty and his colleagues, in conferring on him summa cum laude, highest distinction of the University, expressed themselves as highly satisfied with the way in which he had passed the Examination.[1]

Confusion with Master K.H.

In The Mahatma Letters, Master K.H. mentions a conversation he had with a certain "G. H. Fechner." Trying to verify this statement, C. C. Massey wrote to Dr. Hugo Wernekke, at Weimar, Germany, inquiring "whether Professor Fechner ever had such a conversation with an Oriental whom we could thus identify with Koot Humi." He received the following answer from Professor Gustav T. Fechner:

What Mr. Massey enquires about is undoubtedly in the main correct; the name of the Hindu concerned, when he was in Leipzig, was however, Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya, not Koot Humi. In the middle of the seventies he lived for about one year in Leipzig and aroused a certain interest owing to his foreign nationality, without being otherwise conspicuous; he was introduced to several families and became a member of the Academic Philosophical Society, to which you also belonged, where on one occasion he gave a lecture on Buddhism. I have these notes from Mr. Wirth, the Librarian of the Society, who is good enough to read to me three times a week. I also heard him give a lecture in a private circle on the position of women among the Hindus. I remember very well that he visited me once, and though I cannot remember our conversation, his statement that I questioned him about the faith of the Hindus is very likely correct. Apart from this I have not had personal intercourse with him; but, after his complete disappearance from Leipzig, I have been interested to hear about him, and especially to know that he plays an important role in his native country, such as undoubtedly he could not play here.[2]

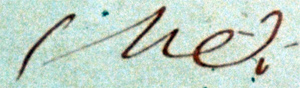

C. C. Massey assumed that "Nisi Kanta Chattapadhyaya" was a pseudonym used by Master K.H. However, this is not the case. Charles J. Ryan reports[3] that Katherine Tingley met Dr. N. K. Chattopadhyaya when she was in Bombay in 1896, and received an autograph copy of his book, "The Reminiscences of the German University Life,"[4] where he talks about his encounter with Prof. G. T. Fechner.

An Important Correction

by Charles J. Ryan

[Reprinted from The Canadian Theosophist, December 15, 1936, pp. 326-329.]

Editor, Canadian Theosophist: - May I draw attention to one or two points in regard to Mr. H. R. W. Cox’s excellent defence of H.P.B. against the most recent attack. The first deals with a statement in your August number.

On pages 173-4 Mr. Cox discusses the problem of the Hindu who met a certain scholar named Fechner, and quotes Mr. Basil Crump’s Evolution. The main points are these: In The Mahatma Letters, p. 44, the Master K.H. mentions a conversation he had "one day" with a certain "G. H. Fechner", but does not say when or where it took place. Mr. Crump, in Evolution, informs us that C. C. Massey, once a leading Theosophist, received information from Leipzig that a Professor Fechner, living there, remembered having met a Hindu at some unnamed period and having heard him lecture. The Hindu also visited Professor Fechner. The Professor said that the name of the Hindu was Nisi Kanta Chattapadhyaya, and that he was not particularly conspicuous. Mr. Massey seems to have thought that he had, in this way, received independent evidence of the presence of the Master K.H. at Leipzig in the earlier ‘seventies, for he explains the reason that Professor Fechner did not know the name Koot Hoomi by a very reasonable supposition, viz.:"In case it may be wondered why he [the Master K.H.] used a different name, it may be mentioned that when members of this Order have to travel in the outer world they always do so incognito."

Mr. Cox appears to agree with Massey, or he would not quote the above remark in his defence of H. P. Blavatsky against the Messrs. Hares’ charges.

Unfortunately Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya and the Master K.H. are two different persons, and the argument is therefore not valid, useful as it would be if confirmed. The former was a well-known Hindu gentleman, Principal of the Hyderabad College and author of sundry interesting works on Oriental, philosophical, and other subjects. He was evidently interested in Theosophy, for he presented Katherine Tingley, when she was in Bombay in 1896, with an autograph copy of one of his books, now in the Oriental Department of the Theosophical Library at Point Loma, California.

The first article or chapter in this book is called "The Reminiscences of the German University Life," and it is a report of a lecture by Dr. N. K. Chattopadhyaya on April 30, 1892 at Secunderabad. In this chapter he says:"I once met Prof. Gustav Fechner, the author of a book called "Psycho-Physik" in which he has enunciated certain laws whose importance . . . . is as great as Newton’s Law of Gravitation . . . . I had the privilege of escorting the old sage home and on the way he asked quite a number of questions about the Yogis and the Fakirs of India . . . Seeing more of him by and by I came to discover that he was quite a mystic, and had actually written a book called the "Zend-Avesta" a masterly exposition of Vedantic pantheism in the light of modern science."

The "Sage" was, of course, the famous Gustav Theodor Fechner.

Turning to The Mahatma Letters, we find that the Master’s conversation "one day" was held with a certain G. H. Fechner, and, as mentioned above, it was not connected with Leipzig. Question: was the Master K.H. referring to some unknown Fechner whose initials were G. H. and not G. T. and who has not been identified? That seems highly improbable. Is it more likely that the H. is a mere slip of the pen or even a typographical error, and that the Master really referred to the eminent philosopher, with whom he had a short conversation, probably so short that it had been quite forgotten by G. T. Fechner, who only recollected N. K. Chattopadhyaya.

However this may be, Professor Gustav T. Fechner’s message to C. C. Massey cannot be used as if it related to the Master K.H., because the Professor definitely states that his Hindu was Chattopadhyaya, and the latter positively confirms the fact. We have learned from other sources that the Master spent some time in Germany, but I am not aware that Leipzig is mentioned in Theosophical literature in that connection. In the Sinnett letters, H. P. Blavatsky says:". . . Wurzburg. It is near Heidelberg and Nurenberg, and all the centres one of the Masters lived in, and it is He who advised my Master to send me there. . ." (p. 105)

My second point relates to what the Hare Brothers call the "notable admission" by H. P. Blavatsky in connection with alleged Mahatma letters sent by her to importunate claimants for advice on their personal, worldly affairs - not connected with Theosophy....

Charles J. Ryan.

General Offices, Theosophical Society,

Point Loma, California.

Writings

• The Yatras, or the Popular Dramas of Bengal. Ca. 1882. 16 editions published between 1882 and 1976 in English.

• Buddhism and Christianity, with an Appendix on Nirvana. London, 1882. 24 pages. Translated from the German in Indische Essays. The German edition Buddhismus und Christenthum. Mit einem Anhang über das Nirvâna was also published in 1882.

• Indische Essays. Zurich, 1883. Five editions published in 1883 in German and other languages.

• Three Lectures: the Reminiscences of the German University Life ; The True Theosophist ; and the Mricchakatikam, or, The Toy Cart. [Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar]: [Verlag nicht ermittelbar], gedr. 1895. 89 pages. Two editions published in 1895 in English.

• "Reminiscences of German University Life": a lecture delivered on the 30th April, 1892. 1901 in English.

• "The True Theosophist, or, Moral and Spiritual Culture: a Lecture". 1892 in English.

• "Mricchakatika or, The toy-cart of King Sūdraka; a study". Mysore: Graduates' Trading Association Press, 1902. English.

• The Mystic Story of Peter Schlemihl. Written with Adelbert von Chamisso. Mysore: Graduates' Trading Association Press, 1902.

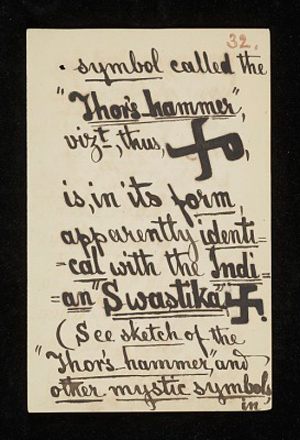

• Lecture on Zoroastrianism. 1894. Madras: The Theosophist Office, 1906. English.

• Why Have I Accepted Islam. Two editions published in 1971 in English. Also published in Chicago, IL: Kazi Publications, [between 1980 and 1997].

• Social and Religious Reformation in India : a lecture delivered in the Rungacharlu Memorial Hall, Mysore, on November 27th, 1901. [Mysore], 1901. English.

• The Study of History: a lecture. 1902 in English.

• Notices and Reviews of Dr. Nishikanta Chattopádhyáya's Lectures. 1897 in English. [With a preface signed: Akhil Chandra Mukerjee.]

• Muhammed, "the Prophet of Islam": a lecture delivered on the 25th of November 1904, at the residence of Mirza Faiaz Ali Khan, Chudderghat, Hyderabad, Deccan. 1900. Sultanpura, Hyderabad: Villa Academy, 1971. English. 36 pages.

• Christ in the Koran. Allahabad: Indian Press, 1907. English.

• Two Essays on the Life and Philosophy of Ibn-Rushd or Averroes. Allahabad : M. Ghulam Muhammad, 1909.

Ibn Rushd (Arabic: ابن رشد; full name in Arabic: أبو الوليد محمد ابن احمد ابن رشد, romanized: Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad Ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rušd; 14 April 1126 – 11 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes (English: /əˈvɛroʊiːz/), was a Muslim Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, Being described as "founding father of secular thought in Western Europe", his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the western world as The Commentator and Father of rationalism. Ibn Rushd also served as a chief judge and a court physician for the Almohad Caliphate.

He was born in Córdoba in 1126 to a family of prominent judges—his grandfather was the chief judge of the city. In 1169 he was introduced to the caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf, who was impressed with his knowledge, became his patron and commissioned many of Averroes' commentaries. Averroes later served multiple terms as a judge in Seville and Córdoba. In 1182, he was appointed as court physician and the chief judge of Córdoba. After Abu Yusuf's death in 1184, he remained in royal favor until he fell into disgrace in 1195. He was targeted on various charges—likely for political reasons—and was exiled to nearby Lucena. He returned to royal favor shortly before his death on 11 December 1198.

Averroes was a strong proponent of Aristotelianism; he attempted to restore what he considered the original teachings of Aristotle and opposed the Neoplatonist tendencies of earlier Muslim thinkers, such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna. He also defended the pursuit of philosophy against criticism by Ashari theologians such as Al-Ghazali. Averroes argued that philosophy was permissible in Islam and even compulsory among certain elites. He also argued scriptural text should be interpreted allegorically if it appeared to contradict conclusions reached by reason and philosophy. In Islamic jurisprudence, he wrote the Bidāyat al-Mujtahid on the differences between Islamic schools of law and the principles that caused their differences. In medicine, he proposed a new theory of stroke, described the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease for the first time, and might have been the first to identify the retina as the part of the eye responsible for sensing light. His medical book Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb, translated into Latin and known as the Colliget, became a textbook in Europe for centuries.

His legacy in the Islamic world was modest for geographical and intellectual reasons. In the west, Averroes was known for his extensive commentaries on Aristotle, many of which were translated into Latin and Hebrew. The translations of his work reawakened western European interest in Aristotle and Greek thinkers, an area of study that had been widely abandoned after the fall of the Roman Empire. His thoughts generated controversies in Latin Christendom and triggered a philosophical movement called Averroism based on his writings. His unity of the intellect thesis, proposing that all humans share the same intellect, became one of the most well-known and controversial Averroist doctrines in the west. His works were condemned by the Catholic Church in 1270 and 1277. Although weakened by condemnations and sustained critique from Thomas Aquinas, Latin Averroism continued to attract followers up to the sixteenth century.

-- Averroes, by Wikipedia

Additional resources

• "The Identity of Koot Hoomi of Kashmir" blog entry from the American Minervan. Accessed Jun 14, 2019.

Notes

1. National Indian Association, Journal of the National Indian Association (1883), 128.

2. Echoes of the Past: Master Koot Hoomi by Mary K. Neff

3. An Important Correction by Charles J. Ryan

4. Three Lectures : the Reminiscences of the German University Life ; The True Theosophist ; and the Mricchakatikam, or, The Toy Cart by Nishikânta Chattopâdhyâya

*************************

Chapter II: The Origin of the Yatra [Excerpt from The Bengali Drama: It's Origin and Development]

by P Guha-Thakurta

1930

If we carefully examine all the older and more primitive forms of dramatic art, even in peoples very far removed from each other geographically and ethnologically, we notice that “drama” in its first stage arises almost invariably from mimetic song and dancing as integral parts of some religious or secular rites. It is quite obvious that the Yatras, as we find them to-day, did not owe their origin mainly to the desire for amusements of a secular nature nor were they entirely the outcome of religious ritual. The name “yatra” literally means a “procession.” A “yatra” originally may have been such a procession as was customary with worshippers and devotees at the time of the regular festivals of their own god or cult. Some kind of musical performance and sympathetic dancing must have formed a part of the procession. Even when the “yatra” no longer remained rigidly connected with religious ceremonies at a regular place of worship, it was still called by its original name, “procession.” Professor Sylvain Levi observed: “Associes aux processions (Yatras) du culte ces spectacles en prirent le nom, et ils le garderent encore après s’etre detaches des ceremonies religieuses pour mener une existence independente.”1 [Google translate: Associated with the processions (Yatras) of the cult these spectacles took the name from it, and they kept it even after having detached themselves from the religious ceremonies to lead an independent existence.] Though one may trace a close connection between primitive drama and music and religious ritual in all countries, it should not be forgotten that the Yatras of Bengal differ in many important characteristics from all other varieties of dramatic representation, whether ancient or modern, and whether in the east or west. The difference lies not so much in the actual types of plays represented by the Yatras as in the specific circumstances under which the performances used to take place and still take place. We will go into this question in greater detail in subsequent chapters.2 The main difficulty in the way of arriving at definite conclusions in regard to the actual sources of the Yatra is the total absence of a chronological history of the older Yatras and their writers. The existing specimens belong to a much later period from 1800 downwards. If we were in possession of a really authentic list of all the Yatras, whether still in existence or not, we could have surmised something about their true nature and also the earlier methods of their production. It is quite probable that at a very early stage the Yatrawalas used to extemporize the music and words of the plays to suit a specific religious festival or social entertainment and that they made no serious attempt at literary composition or publication. We have also no means of discovering whether the religious festivals with which the Yatras were so closely associated in the beginning, are in any way similar to those held in ancient India in honour of the various gods and goddesses. In fact, we know only very little about the so-called “dramatic” festivals of ancient times. The account of alleged “dramatic spectacles” exhibited before the two disciples of Buddha, given in the early Buddhist literature and mentioned by Csoma Korosi,3 does not throw any real light upon the problem of historical sequence. In the third century B.C. Megasthenes speaks of the cult of Siva “as being very predominant among the inhabitants of the mountains who wreathed, anointed, carrying bells and cymbals, followed their kings during the festivals of this god.”4 The same writer describes how the Indo-Aryans belonging to the mountains “worshipped Dionysus or Siva while those of the plain Heracles or Vishnu, and indeed quite especially in his incarnation as Krishna.”5 Another historian tells us: “In the Mahabharata which, however, in its existing redaction, is conceived in the interest of Vishnuism, the cultus which we find most widely spread is that of Civa. He is the Dionysus of Megasthenes, who relates that he was worshipped especially upon the mountains, the rival cultus of Heracles or Krishna being thenceforth dominant in the plains of the Ganges.”6 Dr. Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyay has attempted to prove that all these religious festivals to which references are found in ancient Indian history partook of the nature of the Bengali Yatras and were as well their real precursors.7 This is, of course, extremely conjectural. There is no doubt that religious festivals in the form of dramatic pantomimes used to be performed in ancient India in connection with various popular gods and heroes, but certainly there is no historical evidence to prove a continuous evolution of these festivals or these spectacular performances. Lassen seems to have taken the right view in regard to this whole question: “There cannot be anything contrary to the supposition that similar festivals with similar representations were also celebrated at a much earlier period, although it must be reserved to further researches to show how early this was and of what nature these festivals really were.”8

The contention that the Yatra developed entirely or mainly in connection with the cult or worship of Krsna is open to objection on some very simple and obvious grounds. Firstly, the historical facts and literary data which generally give rise to this theory are quite insufficient and one-sided. For instance, Dr. Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyay attempts to prove it9 by a very exclusive treatment of a handful of Krsna-Yatras of only one well-known Yatrawala, Krsna Kamal Gosvami, published between 1860-71. Secondly, the repeated and persistent mention of Jaydeb’s Gita Gobinda, as if it were a Bengali Yatra, has led the champions of the Krsnaite origin of the Yatra into obvious mistakes. Gita Gobinda is not a Bengali drama; it is written in Sanskrit. Although it presents some traits of resemblance with some of the Krsna-Yatras, it can hardly be regarded as a representative of the Bengali Yatra proper. It is quite true that Bengal has for a long time been the stronghold of Vaisnava thoughts and ideas and that the religious and aesthetic movements started by Chaitanya [1486-1534] and his companions, have influenced Bengali life and literature to an enormous extent. But it should not be forgotten that religion of many forms and cults is inseparably connected with the life of the Hindus. The historian Barth bears witness to “the religious ardour with which the militant parties of the different sects maintain the exclusive title of their god to supremacy and adoration.”10 We know that in Bengal as well as in other parts of India, the cult of Siva flourished side by side with the cult of Krsna, and in fact, in point of historical time, the Siva cult is believed to have preceded the Krsna-cult.11 In the pre-Muhammadan period of Bengali history, Saivism grew up as a strong religious power, combated Buddhism, and succeeded in reviving and reinstating Hinduism in Bengal. It was not until much later, during the time of the Pauranic Renaissance in Bengal that Saivism declined and was overshadowed by the new Sakta-cult.12 An old Bengali journal named “Soma Prakas” is mentioned13 as having contained a statement to the effect that the Yatras that were in existence long before the coming of Chaitanya depended, almost without exception, on Sakta subjects and at that time the Krsna-Yatra was not even heard of. The Sakta cult, which in Bengal for the most part consists in the worship of the “Divine Mother” in the form of the goddess Kali or Durga or any of her other incarnations such as Chandi or Manasa, found its most characteristic expression in the popular Chandi-Yatras and Bhasan-Yatras. Most likely the Chandi-Yatra grew out of a very old type of musical performance called Chandir Gan (The Song of Chandi). The best specimens of the Chandi-Yatra in Bengal are those by Guru Prasad Ballabh of Farasdanga. The Bhasan-Yatra is usually connected with the annual festival of Manasa Devi in the villages of lower Bengal. The festival is both social and religious. Boat races and ‘mela’s (village fairs are held during the day and at night the worshippers keep vigil, and chant poems before the temple of the goddess. The songs are taken from the popular stories connected with Behula and Phullara and also from the events in the life of Chamd Saodagar (Chamd, the merchant) who, having fallen under the wrath of Manasa for defying her, wanders in many lands and is ultimately driven by strange circumstances to worship her. Bhasan-Yatras produced by Lausen Baral were among the best of their kind.14 The cult of Siva was also represented by those popular plays which dealt with the domestic scenes on Mount Kailas, the mythical abode of Siva. Mr. Binay Kumar Sarkar15 gives us an interesting account of an ancient Hindu institution, partly religious and partly dramatic, known as the Gambhara festival, which is entirely connected with the cult and worship of Siva. It used to be held in honour of Siva regularly every year in different parts of Bengal, Assam and Orissa. Mr. Sarkar things that “to a certain extent, the literature of the Gambhira-cycles may be compared with the Mystery and Miracle plays in old English and No-plays of Japan.”16 Mr. Sarkar traces the origin of the Gambhira institution from the very earliest times through the Vedas, epics, Buddhistic literature and the records of Hiuen Tsang, indicates the total extent of the geographical area through which it actually spread, deals with the dramatic devices and methods by which it was presented to the people, and points out its influence upon Bengali culture and folk-arts. Mr. Sarkar says, “The educative influence of such agencies as popular festivals is very well illustrated by their effects upon the literature, arts, industries, morals, and public spirit of the people who took part in this socio-religious ceremony in connection with the worship of Siva.”17 Besides the Saiva and Sakta Yatras, there actually existed in Bengal many other different varieties of Yatra such as the Rama-Yatra and Vidya-Sundar Yatra which were also very widely popular in their own time. Jay Chandra, Prem Chamd and Ananda were well-known Adhikaris or Yatrawalas, who became renowned in Bengal by their productions of the Rama Yatra. Gopal Uriya (1819-59) was the foremost among the producers of the Vidya-Sundar-Yatra. The songs and dances of Hira, a flower-girl, constituted the chief feature of all Vidya-Sundar-Yatras.18 The existence of Yatras other than Krsna-Yatras before the latter appeared in Bengal cannot, therefore, be doubted. Even Krsna Kamal Gosvami, to whose Yatras Dr. Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyay specifically refers, remarks19 that numerous plays based on the epics were existent in his own time, and the reason why he himself thought of writing some Krsna-Yatras was that he found the others either too learned for ordinary people or too much vitiated by obscenity. Krsna Kamal (1810-88) is perhaps the most renowned of all the reformers of the Yatra. The Krsna-Yatra in Bengal owes its increasing popularity and refinement almost entirely to Krsna Kamal. His first Yatra, called Svapna Bilas (Dream Pleasure) was composed about 1835. It was performed immediately by several Yatra-parties in Dacca. It was published some years later and had an amazing circulation. In a preface to his second production named Bichitra Bilas (The Amour Wonderful), Krsna Kamal wrote about Svapna Bilas: “The public probably liked the work; otherwise why should there be a sale of 20,000 copies in such a short time?” Rai Unmadini (The Frenzied Radha) which came after Bichitra Bilas, is perhaps his best and most finished Yatra. His other minor Yatras are Bharat Milan (The Meeting with Bharat), Nimai Sanyas (The Renunciation of Nimai), and Gostha (A Pastoral Idyll). Except Bharat Milan, in which the episode of the meeting of Bharat and Rama when Bharat implores Rama to come back to Ayodhya, is taken from the Mahabharata, all the Yatras of Krsna Kamal deal with incidents in the life of Krsna in Brndaban. His Krsna-Yatras were, as a rule, characterized by a strong emotional lyricism and the moral earnestness of a true Vaisnav. The Krsna-Yatra was developed and popularized by a host of other writers and producers, both before and after Krsna Kamal. The name of Sisuram Adhikari will always be remembered as one of the ablest and most successful producers of the Krsna-Yatra. He was a contemporary of Ram Prasad (1718-75) and Bharat Chandra (1722-60). An account of him appears in Rajendra Lal Mitra’s Bibidhartha Samgraha.20 The improvements Sisuram introduced into the Yatra were later carried on by his well-known disciple Sridam-Subal. Sridam-Subal also found a very worthy successor in Paramananda Das. At the time of Paramananda and his contemporary Prem Chamd of Vidya-Sundar-Yatra fame, the Krsna-Yatra reached its high-water mark. Paramananda introduced a new feature into the songs well known as “tukko” (which means the turning of the last part of a song written in payar style into a kirtan ending), which became very popular. After Paramananda’s death, his mantle fell on Gobinda Adhikari (1798-1870). Besides being a good producer, Gobinda was an original composer of songs, most of which were written in alliterative verse. Gobinda discarded his master’s “tukko” style of singing which was, however, revived later by his own disciple Badan. After the death of Badan, the Yatra began to decline in Bengal. The tradition was, however, carried on by inferior men like Brajanath and Nilkantha but they were unable to save the Yatra from its inevitable fate. It is quite evident that the later improved tone and healthier development of the Yatra came as a direct result of the Vaisnava revival under Chaitanya and his followers. Its gradual growth and expansion went hand in hand with the dissemination of the cult of Krsna. In fact, there actually came in the history of popular dramatic representations in Bengal a time when the Krsna-Yatra over-shadowed all others and became the most convenient instrument in the hands of the Vaisnavas to propagate their ideas amongst the masses.

From the above brief survey of the different varieties of the Bengali Yantras, it appears quite clearly that the theme of a Yatra was by no means necessarily taken from the life and adventures of Krsna, but was quite as often adapted from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, Pauranic legends, folk-tales, and mythology. Professor Sylvain Levi, while speaking of the very wide range of topics dealt with in the Yatras, observed: “Les auteurs ne sont pas interdit toutefois de sortir du cycle Krishnaite; ils ont emprunte sans scruple leurs sujets au Mahabharata et au Ramayana … le civaisme meme a prete parfois ses divinites et ses legends: temoin les amours de Civa et Parvati.”21 [Google translate: The authors are not however forbidden to leave the Krishnaite cycle; they unscrupulously borrowed their subjects from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana… the civaisme itself sometimes lent its divinities and its legends: witness the loves of Civa and Parvati.] Sir J.H. Marshall22 gives us a very interesting descriptive list of the various existing types of dramatic representations in India. It shows a large quantity of different themes which are adopted for the various performances and the many religious cults and institutions with which these are associated. There is no doubt that in Bengal, as elsewhere, the different social and religious institutions largely contributed to the development of literature and fine arts. As a matter of fact, at no point of their literary or religious history did the people of Bengal completely neglect or forget to celebrate in song, drama, poetry or ritual their innumerable gods and goddesses.23 A country like Bengal which is so old may quite reasonably claim to have a history or at least a legendary past of its own, the most important events of which will naturally have been utilized in a suitable manner for purposes of popular entertainment and instruction. It may be concluded, therefore, that the popular plays like the Yatra did not necessarily confine themselves to the worship and cult of Krsna or draw their inspiration only from the literature or history that gathered round this god, but drew freely from the Puranas and mythology, folk-legends and epic stories and, in fact, from every possible indigenous source.

The Bengali Yatra may be regarded then as a kind of community drama originating in the religious worship of the various gods and goddesses of antiquity and serving as a convenient medium through which the religious and social ideas and feelings appropriate to the different festivals and holidays, found a natural expression. Divine worship as a whole suggested the possibilities of dramatic representation, for which the epics and folk-literature gave characters, and the ancient mythology and Puranas furnished stories. In fact, no other type of popular drama has sprung so directly out of the peculiar conditions of Bengali life, nor has any other form of play developed in such definite and close connection with the distinctive aesthetic ideas and religious beliefs of the Bengali people. The merits and defects of the Yatra can be fully understood only if we bear in mind the essential characteristics of Bengali culture and the particular temperament and sentiments to which it has always appealed. To the entire rural Bengali community, the Yatras have been as familiar as their daily routine of life, acquainted as they are with all the traditional stories with which these plays deal. They recognize their heroes of history and legend as soon as they appear in a play and they accept from generation to generation, without the slightest demur, all the old tales of romance and mythology exactly in the way these are presented and interpreted to them through the Yatras.24 The Yatras most clearly demonstrate what a firm hold the Puranas, epics and mythology of the past have retained on the minds of the Bengali people. We are not, therefore, surprised in the least that the dramatic devices and methods of the Yatra should have remained pretty much the same for ages, and that the successive playwrights and Yatrawalas should have utilized the same stories over and over again.

_______________

Notes:

1. Le Theatre Indien, p. 394.

2. See Chaps. IV and V, pp. 20-30.

3. Asiatic Researches, xx, 50. See also Weber, Indische Literraturgeschichte, p. 217. Also Lassen, Indische Alterhumskunde, vol. ii, p. 502.

4. Indische Alterthumskunde, vol. ii, pp. 690 and 698.

5. Indische Alterthumskunde, vol. iii, p. 453; see also vol. i, pp. 795 and 925. Cf. Megasthenes, Indica, p. 135, ed. by Schwanbeck. Lassen's interpretation of the passage from Megasthenes has been contested by A. Weber (Indische Studien, ii, p. 409)

6. A. Barth, The Religions of India, trans. by J. Wood (1882), p. 163.

7. The Yatras or The Popular Dramas of Bengal, pp. 45 ff.

8. Indische Alterthumskunde, chap. ii. p. 505.

9. See The Yatras or The Popular Dramas of Bengal, pp. 2 ff.

10. The Religions of India, p. 183.

11. See D.C. Sen, History of Bengali Language and Literature, pp. 63-73 and 235-50.

12. Ibid., pp. 252-362.

13. See Amarendra Nath Ray's article entitled "Yatra Katha" in the first number of Rup o Ranga, 1321 B.S. (A.D. 1914-15).

14. For a fuller account of the cult of Manasa Devi, the folk literature connected with her, and the places where festivals are still regularly held in her honour, see D.C. Sen, History of Bengali Language and Literature, pp. 256 ff.

15. The Folk-Element in Hindu Culture, pp. 14 ff.

16. Ibid., p. 20.

17. Ibid., pp. 14-15.

18. A very interesting account of the Vidya-Sundar Yatras in Bengal appeared in Sanjib Chandra Chatterji's Yatra-Samalochana (A critical review of the Yatra), Calcutta, 1907.

19. See The Collected Works of Krsna Kamal Gosvami, 2nd ed., pp. 179-80.

20. Mentioned by Mr. Amarendra Nath Ray. See Rup o Ranga, first number, 1331 B.S. (A.D. 1924-25), p. 19.

21. Le Theatre Indien, p. 394.

22. See Dr. William Ridgeway's Dramas and Dramatic Dances of non-European Races, pp. 172-210.

23. "The Hindu tendency to deify the energies, nature-forces, or personal attributes or emotions has constructed all the gods and goddesses of India, practically speaking, as so many embodiments of the various phases of the country itself and of the culture it has developed through the ages. And the invention of deities has not yet ceased." -- Mr. B.K. Sarkar, Folk-Element in Hindu Culture, p. 260.

24. It may be mentioned in this connection that Aristotle approved of the choice of legendary themes for the Attic drama because of the inherent Greek faith in the mythology of the country and its intimate connection with the traditional history of the people. -- See Politics, C9.

**************************

Retrospect of the Year 1876-7, Excerpt from The Brahmo Year-Book for 1877: Brief Records of Work and Life in the Theistic Churches of India

edited by Sophia Dobson Collet

"Mercury" Steam Printing Works, High Street, Bedford

1877

Lastly, it should be mentioned that among the Indian youths who come to England for study, several Brahmos have won honourable distinction. Mr. Krishna Govinda Gupta, C.S., and Mr. Ananda Mohan Bose, M.A. Cantab., now a rising barrister of Calcutta, returned home in 1874; and during the past year, Mr. Prasanna Kumar Ray, having taken the degree of Dr. of Science (in Mental Philosophy) at the Universities of London and of Edinburgh, returned to India, and was shortly afterwards appointed Assistant-Professor at Patna College, and in the department of physical science. A Dacca friend informs me that Dr. Ray "is the President of a scientific society established at Patna, and periodical lectures on scientific subjects are delivered by himself and other Bengali gentlemen under its auspices." He also conducts divine service in the local Brahmo Somaj. -- Another young Brahmo, Babu Nisi Kanta Chattopadhaya, after studying some time at Edinburgh, and for two or three years at Leipzig, has lately been appointed Professor of Oriental Languages at the University of St. Petersburgh, an appointment probably resulting from the reputation which he has gained from various lectures on Oriental subjects which he delivered in Germany last winter. These lectures are now appearing in the Leipzig Duetsche Wochenschrift, and the two which have reached me are both able and interesting. The first, on "Buddhism and Christianity," [Buddhism and Christianity: The Chronology of the Hindus. Lectures in German by Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya. Published in the Deutsche Wochenschrift (German Weekly Journal), Nos. 1, 2, 11, 12, and 13. July and September, 1877. Leipzig: Carl Hildebrand. Thalstrasse 31.] has given much offence in some religious circles in Germany, from its freely expressed views on certain points. Doubtless the author's conception of Christianity is inadequate, and rests upon an insufficient knowledge of Christian life and history; but he warmly appreciates the moral idealism of Christ, and he writes to me thus of his general position towards Christianity: -- "It is not at all true that it is antagonistic, as is fancied by many here. In my lectures I have proceeded as objectively as possible, and I have consciously neither exalted Buddhism nor depreciated Christianity. Those who know me, know that I love the spirit of Christ, the life in Jesus, as much as ever."

It only remains to add that these four Brahmo students are all natives of East Bengal, and commenced their career at the Dacca College.

************************

Personal Intelligence, from Journal of the National Indian Association in Aid of Social Progress and Female Education in India

Dominus Illuminatio Mea [Lord is my light]

Sir M. Monier-Williams, KCIE

1883

Dominus Illuminatio Mea [Lord is my light]

Mr. Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya has taken the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the University of Zurich. The Dean of the Faculty and his colleagues, in conferring on him summa cum laude, the highest distinction of the University, expressed themselves as highly satisfied with the way in which he had passed the Examination.

****************************

1879, Excerpt from Masters and Men: The Human Story in the Mahatma Letters (a fictionalized account)

by Virginia Hanson

The Theosophical Publishing House

Madras, India

c 1980 The Theosophical Publishing House

Most of the Letters are over the signature of the Mahatma Koot Hoomi, usually signed simply "K.H." A Kashmiri Brahmin by birth, at the time of the correspondence he was a Buddhist. Koot Hoomi is a mystical name which he instructed H.P.B. to use in connection with his correspondence with Mr. Sinnett. It is possible that his real name was Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya, as that seems to have been the name by which he was known when he was attending at least one European University. He was fluent in both English and French and was sometimes affectionally spoken of by the Mahatma Morya as "my Frenchified K.H."

At one time, under special circumstances, the Mahatma Morya took over the correspondence temporarily. He too used only his initial as a signature. "He was a Rajput by birth," said H.P.B., "One of the warrior race of the Indian desert, the finest and handsomest nation in the world." He was "a giant, six feet eight, and splendidly built; a superb type of manly beauty." The Mahatma K.H. referred to him humorously as "my bulky brother." He was not proficient in English and spoke of himself as using words and phrases "lying idle in my friend's brain" -- meaning, of course, the brain of the Mahatma K.H.

In 1870, the same year that Keshub visited England, two other Indians took ship from England to America. They were a Bombay textile magnate called Moolji Thackersey (Seth Damodar Thackersey Mulji, died 1880) and Mr. Tulsidas. Josephine Ransom, an early historian of the Theosophical Society, writes that they were “on a mission to the West to see what could be done to introduce Eastern spiritual and philosophic ideas.” Traveling on the same boat was Henry Olcott, fresh from his experiences in London’s spiritualist circles. Olcott was sufficiently impressed by this shipboard meeting to keep a framed photograph of the two Indians on the wall of the apartment he was sharing with Blavatsky in 1877. It was one evening in that year that a visitor who had traveled in India (sometimes identified as James Peebles) remarked on the photograph. Olcott writes in his memoirs of the consequences of this extraordinary series of coincidences:I took it down, showed it to him, and asked if he knew either of the two. He did know Moolji Thackersey and had quite recently met him in Bombay. I got the address, and by the next mail wrote to Moolji about our Society, our love for India and what caused it. In due course he replied in quite enthusiastic terms, accepted the offered diploma of membership, and told me about a great Hindu pandit and reformer, who had begun a powerful movement for the resuscitation of pure Vedic religion.

This reformer was Swami Dayananda Saraswati (1824-1882). In 1870 he was still an eccentric traveling preacher with no aspirations to international influence: something that grew on him precisely after meeting the Brahmo Samajists. He met Devandranath [Debendranath] Tagore in 1870; in 1873 Keshub Chunder Sen gave him the advice (which he took) to stop wearing only a loincloth and speaking only Sanskrit. Indefatigably stumping round the subcontinent, Dayananda founded his “powerful movement,” the Arya Samaj, in 1875. This chronology suggests that in 1870 Thackersey was probably coming to America as a representative of the Brahmo Samaj, but that by the time Olcott got in touch with him again, he had transferred his allegiance to the Arya Samaj.

The Arya Samaj was more radical than any wing of the Brahmo Samaj, on which it was partially modeled. Dayananda was a monotheist who believed in the Vedas as the sole revealed scripture and the basis for a universal religion. The various gods addressed in the Vedic hymns (Agni, Indra, etc.), he explained as aspects of the One, and he was prepared to demonstrate how these ancient texts contained all possible knowledge of man, nature, and the means of salvation and happiness. Of the quarrels between the various religions, he wrote: “My purpose and aim is to help in putting an end to this mutual wrangling, to preach universal truth, to bring all men under one religion so that they may, by ceasing to hate each other and firmly loving each other, life in peace and work for their common welfare.” He had no respect whatever for Brahmanism: for their scriptures, rituals, polytheism, caste system, and discrimination against women. Unfortunately for his opponents, he was immensely learned and articulate, could out-argue most pundits, and had, in the last resort (which often seems to have occurred) the advantage of being 6’9” tall and broad to match.

From Dayananda’s point of view, the Brahmo Samajists had erred both in their failure to recognize the supremacy of the Vedas, and in their too-ready embrace of the errors of other religions. They were moreover too addicted to Brahmanic customs and privileges. Here is a contemporary summary of his social principles:He says that no inhabitant of India should be called a Hindu, that an ignorant Brahmin should be made a Shudra, and a Shudra, who is learned, well-behaved and religious should be made a Brahmin. Both men and women should be taught Language, Grammar, Dharmashastras, Vedas, Science and Philosophy. Women should receive special education in Chemistry, Music and Medical Science; they should know what foods promote health, strength and vigour. He condemns child marriage as the root of the most of the evils. A girl should be educated and married at the age of twenty. If a widow wants to remarry, she should be allowed to do so. According to his opinion, there is no particular difference between the householder and the sannyasi.

It is not surprising that the Theosophists in New York took kindly to the Arya Samaj, at first through correspondence with Thackersey, then through the Bombay branch head, Hurrychund Chintamon, and lastly through Dayananda himself. The two societies were united for a time, though the Theosophists were disillusioned as soon as they discovered the strength of Dayananda's Vedic fundamentalism and his hostility to all other religions. On Dayananda's unexpected death, Blavatsky wrote a generous obituary in The Theosophist for December 1883. She appreciated him for defending what he saw as the best of his native heritage against the priestcraft of Brahmins and Christians alike, and for his leadership in an enlightened social policy of which she could only have approved.

As the Arya Samaj continued to flourish after Dayananda's death, it became a rallying point for that movement of Hindu nationalism that wanted neither to turn back the clock to Brahmanic theocracy, nor to embrace Western materialism along with the benefits of science and technology. What Rammohun Roy had set in motion, the Arya Samaj carried forward into the era of the Indian National Congress and the independence movement of the twentieth century. Dayananda himself died -- some said poisoned -- at the time when his mission was beginning to have real success among the North Indian rulers, but he had done enough to be celebrated as a father-figure by leaders of Indian independence such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, and Aurobindo Ghose.

-- The Theosophical Enlightenment, by Joscelyn Godwin