by John D. Ray

World Archaeology

Volume 17 No. 3

©R.K.P. 1986

In Pliny's account, Menes was credited with being the inventor of writing in Egypt.

-- Menes [Mneues] [Mannus] [Manu], by Wikipedia

Abstract

The cultural history of ancient Egypt is markedly different from that of contemporary Mesopotamia, and the adoption of the idea of writing by the Egyptians conforms to a general pattern, which shows the tendency of Egypt to adopt and perfect inventions made elsewhere in the Near East. Theories of a conquering 'dynastic race', which gave rise to Egyptian civilisation, are unnecessary. Hieroglyphs show many of the signs of deliberate invention, probably in association with the royal court, appearing suddenly, and developing rapidly. They are so well suited to the underlying language, one of the Afroasiatic group, that their creation seems to be deliberate. Uniconsonantal, or 'alphabetic', signs are a striking and unique feature of the system, which was essentially complete by 3000 B.C.

Egyptology and Assyriology can be seen as complementary sciences, celestial twins or ugly sisters, depending on the standpoint of the describer. Egyptology is the slightly older sister - if we take the date of the respective decipherments to represent the moments of their birth as disciplines - and both have a similar history of development, liberating themselves slowly from Biblical and classical studies, and gradually finding their own places. Egyptology is also the more romantic and popular of the two, and perhaps the more extrovert; Assyriology compensates for this in the range of material, especially texts, at its disposal, and the growing challenges that it presents to its admirers.

Comparisons between the two disciplines go hand-in-hand with attempts to characterise the two civilisations which gave rise to them, and the best-known example is probably the one which occupies most of Before Philosophy, otherwise known as The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man (Frankfort). Such comparisons are designed to stimulate as much as to illuminate, and it is in the same spirit that we can suggest another, superficial and light-hearted though it has to be: the political, and to some extent the cultural, history of Egypt has several points in common with that of modern France, whereas if we look for a parallel with that of Mesopotamia, we can see things which remind us of modern Germany. The situation of Egypt in the ancient world was relatively secure: her borders were easily defended, except for the vulnerable section in the north-east, and this relative isolation was reinforced by a favourable climate and the ability to support a comparatively large population. Within the country political unity, although by no means constantly achieved in Egyptian history, was fairly easy to maintain and tended to centre upon a royal court with far-reaching powers. Local regionalism existed, and could assume a strong form, but in general the monarchy was able to overcome this, either by force or by inducement. With the rise of this centralised state - the first in history - went a pattern of culture which was essentially imposed from above by the courtly circles; and the strong visual sense, and all-pervading sense of style, as in France, is one of the most noticeable and appealing aspects of ancient Egypt. Egypt, like France, was also an absorber of immigrants, who rapidly adopted Egyptian culture and rose to positions of prominence in the state by virtue of doing so. The price that has to be paid for these advantages is a certain cultural complacency and even a 'superiority complex', which can hamper original perceptions. Egypt's role wasthat of a perfecter of ideas, rather than an inventor; most of the innovations in the ancient Near East come from outside Egypt, but Egypt, once it adopts a new idea, produces a form of it which is often more effective than it was in its original home. Mesopotamia, on the other hand, does have more in common — to attempt a'generalisation - with the experience of Germany: open frontiers leading to frequent invasion and disruption, a less favourable environment for the growth of political unity, and a restiveness which leads to unity being imposed by a more militaristic culture (Assyria). The results are a creativity, caused in part by competition between its constituent areas, and a restless profundity in intellectual life which contrasts with the general performance in the visual arts, which is not on the whole the equivalent of Egypt's. This is no doubt an oversimplified view of the two civilisations, but it does hold true for quite a few areas of activity, and the emergence of writing is arguably one of them.

It is worth qualifying this picture slightly, by reminding ourselves of the limitations of archaeology, especially in the Nile valley. Here excavation, until quite recently, has concentrated on remains which are well-preserved and likely to produce objects of art or major texts - which in effect meant that the main emphasis in Egyptian archaeology was on tombs and similar monuments. Town sites have been relatively unrewarding and unattractive: close mud-brick work, combined with constant infiltration by sub-soil water, often in the midst of a modern urban area, could hardly compete with leisurely epigraphy amid the sands of the desert, especially if a sensational discovery was likely to be had. Egyptology, therefore, has less chance of producing economic and social information than Mesopotamian archaeology, where clay tablets are easily preserved in large numbers. The situation is now changing, but it will be quite some time, if ever, before we can be sure that our conclusions about Egyptian society, especially early Egyptian society, are true and not merely dictated by what the inhabitants of that society chose to take into the next world with them. This familiar fact still has to be borne in mind. It may also be true that our notions of what ancient Egypt was like are distorted by the accident that most of our evidence comes from the south; an Egyptologist, if he could be transported magically into the eastern Delta at most periods of Pharaonic rule, might well decide that he was in a country quite foreign to the land of his imagination.

Prehistoric Egypt is best seen in the recent study by Hoffman (1980). Whatever the situation may have been in the Palaeolithic, Egypt of the fourth millennium does seem to exhibit many of the characteristics of later Egypt: a strong cultural unity (except that the Delta and Upper Egypt are still markedly different), artistic creations of a high standard, and, at least to judge from tomb structures and furnishing, an increasedly stratified society, with a leisured or wealthy class creating a demand for luxuries which involves a considerable section of the population. The tone, at least in Upper Egypt, seems to be aristocratic and agricultural, rather than mercantile. Towards the end of the period, however, in the phase known as Nagada II or Gerzean, change seems to occur at an accelerated pace. The main feature of this transformation, other than general changes in the styles and ranges of artefacts, is the adoption of foreign motifs, in particular Mesopotamian, or in some cases Proto-Elamite. These motifs - the cylinder-seal, artistic devices comprising animals with intertwined necks, fashions in clothing, and even architectural designs such as the 'palace facade' - are undeniable, even if the explanation is hard to find. Mere trade seems an inadequate reason, and some Egyptologists have fallen back on the concept of a full-scale invasion, either by way of Syria-Palestine, or by sea around the coasts of Arabia. Inadequate pathology was often used to bolster up this theory, and the 'dynastic race' was created as a convenient model. But if we bear in mind the cultural generalisations suggested above, and if we adopt more recent explanations of how primitive societies can 'take off into a more sophisticated level of culture, we can probably see that Egypt, on the eve of its emergence as a historical state, was adopting foreign influences in order to assist its own development. Mesopotamian and Elamite motifs were chosen, not because of political events, but because they were the only models which fitted her stage of development: and these models, once adapted, were almost entirely discarded as soon as Egypt had found its self-confidence and identity. The young civilisation needed a prop with which to learn to walk; then it could throw away the prop.

Writing was the most important of these adoptions, and the only one which was not to be thrown aside. At the moment it does look as if writing, or rather the idea of writing, was extraneous to Egypt. In Mesopotamia, we can see the gradual emergence of picturewriting as a form of accounting or similar record-keeping, at a date earlier by a couple of centuries than its appearance, Athena-like, from the head of the Egyptian hierarchy. This at least is the accepted wisdom, and it is likely to be right, although Arnett (1982) has produced an interesting alternative. Arnett has made a study of the motifs and decorative signs found quite frequently on predynastic pottery and other artefacts from Egypt, and concludes that a rudimentary writing-system was in use several centuries before the unification of Egypt into a historical state. This is certainly an original idea, although Petrie (1912) experimented with a parallel notion when trying to trace the origin of the alphabet to potters' marks found on predynastic vessels; but the weakness of this sort of argument is that it is merely an extrapolation from later usages. The later hieroglyph for 'foreign land', for example, does occur on predynastic pottery, but since it is merely a schematised drawing of desert hills, it is impossible to say that the sign means what it is used to mean later. It may, in its early stage, be merely an element of design, and some of the other 'hieroglyphs' detected by Arnett are very difficult to explain in the light of their historical values. The more likely conclusion seems to be at the moment that, throughout the predynastic period, characteristically Egyptian ways of portraying the natural world were slowly developed, and that it was from this 'reserve', or artistic repertoire, that the first hieroglyphs were chosen. The same would apply to symbols for gods, or shrines, or even spiritual concepts such as the ka, represented by arms stretched upwards, which are likely to have existed in Egyptian thinking long before the need to create a formal system of writing (Arnett, Plate 16). There is no reason to believe that the Egyptians took their individual hieroglyphs from any foreign source.

What then did the Egyptians adapt from Mesopotamia, when it came to creating a writing system? The simplest answer is probably the best: they took the idea of writing. There presumably came a point in the development of the Egyptian state when some agency responsible for economic and political matters decided on the need for recording its activities. This agency, given what we know about dynastic, and what we can reasonably extrapolate about predynastic, Egypt was almost certainly a royal court, or possibly the sole royal court if there was a 'Pharaoh' in Gerzean or late-Gerzean Egypt. The inscriptions surviving from the first dynasty, even when allowance is made for the one-sided archaeological record, are almost exclusively concerned with royal administration: major cult activities in which the king almost inevitably played a major part, events in palace ceremonial or in symbolic public works, such as cutting large canals, which would have been used to enhance the position of the sovereign and his entourage. The milieu, therefore, is reasonably clear, but the date and the mechanism of the creation of hieroglyphs are much harder to determine.

An obvious point for the date would be the beginning of the first dynasty. Here, according to Egyptian tradition, Menes of This in Upper Egypt conquered the Delta, unified the country, founded Memphis as his capital, and introduced many of the traits of classical Pharaonic culture; although, interestingly, he is not credited with the invention of hieroglyphs. A minimalist modern interpretation of what happened at the beginning of Egyptian history would be that there was no Menes, the search for him among the historical records is therefore meaningless, and that there was probably no unification either; all that happened was that the Egyptians invented writing and began to record their history systematically. The date for this can be obtained by a combination of astronomical data and dead reckoning from later king-lists such as the Turin canon: 3089 + x B.C., where x is the length of the obscure 'first intermediate period'. Considerable attempts have been made by historians to reduce this figure, but it is rather supported by some of the most recent Carbon-14 calibrations (see most cautiously Shaw 1984). A date of 3100 would not be far wrong, therefore, in which case there is a suitable time-lag behind the Mesopotamian introduction of writing.

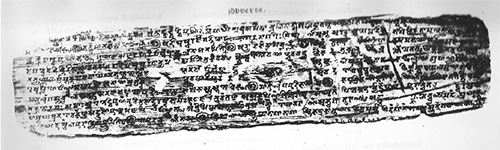

The problem, however, is complicated by the known existence of Egyptian kings before Menes. The Palermo Stone, essentially a fifth-dynasty composition (although almost certainly a much later copy), clearly shows, on a separate fragment, the existence of kings wearing the crown of united Egypt well before 'Menes' and the supposed unification. Names of nine kings of Lower Egypt are also preserved, and outlandish they are, at least by later standards; this may be explicable by their Lower Egyptian origin, or more likely some form of oral tradition has been at work, but the very existence of these names must make us cautious (Sethe 1903). More disturbing are the contemporary monuments of kings, principally from the royal cemetery at Abydos but also from elsewhere, with names such as the increasingly attested Ro or Iry, the obscure Ka or Sekhen, and the better-known Scorpion (reading uncertain), who seems to be almost a prototype of Menes in his achievements (Barta 1982). The embarrassment caused by the existence of these kings is reflected in the term 'Dynasty O' which is frequently applied to them. Names of these kings appear clearly on contemporary monuments such as jars, and even the Scorpion macehead, and this leaves us in no doubt that writing existed in Egypt before the first king of Dynasty I. Our date of 3100 must therefore be raised to 3150 or even slightly earlier, and it is always possible that archaeological discovery will upset this picture even more. 'Menes', therefore, was not the inventor of hieroglyphs.

Can we talk about an invention of writing in Egypt at all? Since, as argued above, the only element necessary to set off a chain reaction within protodynastic Egypt was the knowledge that ways to do the things the Egyptians wished to do existed elsewhere, the realisation that in Sumer pictures of material objects were being used in a punning way to express ideas, or other objects which were impossible to draw explicitly, was the only catalyst required; and this was in fact the only element which was borrowed. Kaplony (1966b, 1972a) speaks blithely of an 'inventor' of Egyptian hieroglyphs who did precisely this, and while this is probably an over-simplification, there are certainly indications within the hieroglyphic system that conscious planning has been applied to the script from the very beginning of its employment. It is distinctly possible, therefore, that one mind may have formulated the basic principles. The Egyptians themselves both confirm this, and beg the question, when they ascribe the creation of writing to the god Thoth (compare the anecdote in Plato, Phaedrus, 274c-275b, where the king of Egypt is presented with the new-fangled system by the god but accepts reluctantly, fearing that his subjects would cease to rely on their memories).

SOCRATES: But there is something yet to be said of propriety and impropriety of writing.

PHAEDRUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: Do you know how you can speak or act about rhetoric in a manner which will be acceptable to God?

PHAEDRUS: No, indeed. Do you?

SOCRATES: I have heard a tradition of the ancients, whether true or not they only know; although if we had found the truth ourselves, do you think that we should care much about the opinions of men?

PHAEDRUS: Your question needs no answer; but I wish that you would tell me what you say that you have heard.

SOCRATES: At the Egyptian city of Naucratis, there was a famous old god, whose name was Theuth; the bird which is called the Ibis is sacred to him, and he was the inventor of many arts, such as arithmetic and calculation and geometry and astronomy and draughts and dice, but his great discovery was the use of letters. Now in those days the god Thamus was the king of the whole country of Egypt; and he dwelt in that great city of Upper Egypt which the Hellenes call Egyptian Thebes, and the god himself is called by them Ammon. To him came Theuth and showed his inventions, desiring that the other Egyptians might be allowed to have the benefit of them; he enumerated them, and Thamus enquired about their several uses, and praised some of them and censured others, as he approved or disapproved of them. It would take a long time to repeat all that Thamus said to Theuth in praise or blame of the various arts. But when they came to letters, This, said Theuth, will make the Egyptians wiser and give them better memories; it is a specific both for the memory and for the wit. Thamus replied: O most ingenious Theuth, the parent or inventor of an art is not always the best judge of the utility or inutility of his own inventions to the users of them. And in this instance, you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.

PHAEDRUS: Yes, Socrates, you can easily invent tales of Egypt, or of any other country.

SOCRATES: There was a tradition in the temple of Dodona that oaks first gave prophetic utterances. The men of old, unlike in their simplicity to young philosophy, deemed that if they heard the truth even from 'oak or rock,' it was enough for them; whereas you seem to consider not whether a thing is or is not true, but who the speaker is and from what country the tale comes.

PHAEDRUS: I acknowledge the justice of your rebuke; and I think that the Theban is right in his view about letters.

SOCRATES: He would be a very simple person, and quite a stranger to the oracles of Thamus or Ammon, who should leave in writing or receive in writing any art under the idea that the written word would be intelligible or certain; or who deemed that writing was at all better than knowledge and recollection of the same matters?

PHAEDRUS: That is most true.

SOCRATES: I cannot help feeling, Phaedrus, that writing is unfortunately like painting; for the creations of the painter have the attitude of life, and yet if you ask them a question they preserve a solemn silence. And the same may be said of speeches. You would imagine that they had intelligence, but if you want to know anything and put a question to one of them, the speaker always gives one unvarying answer. And when they have been once written down they are tumbled about anywhere among those who may or may not understand them, and know not to whom they should reply, to whom not: and, if they are maltreated or abused, they have no parent to protect them; and they cannot protect or defend themselves.

PHAEDRUS: That again is most true.

SOCRATES: Is there not another kind of word or speech far better than this, and having far greater power—a son of the same family, but lawfully begotten?

PHAEDRUS: Whom do you mean, and what is his origin?

SOCRATES: I mean an intelligent word graven in the soul of the learner, which can defend itself, and knows when to speak and when to be silent.

PHAEDRUS: You mean the living word of knowledge which has a soul, and of which the written word is properly no more than an image?

SOCRATES: Yes, of course that is what I mean. And now may I be allowed to ask you a question: Would a husbandman, who is a man of sense, take the seeds, which he values and which he wishes to bear fruit, and in sober seriousness plant them during the heat of summer, in some garden of Adonis, that he may rejoice when he sees them in eight days appearing in beauty? at least he would do so, if at all, only for the sake of amusement and pastime. But when he is in earnest he sows in fitting soil, and practises husbandry, and is satisfied if in eight months the seeds which he has sown arrive at perfection?

PHAEDRUS: Yes, Socrates, that will be his way when he is in earnest; he will do the other, as you say, only in play.

SOCRATES: And can we suppose that he who knows the just and good and honourable has less understanding, than the husbandman, about his own seeds?

PHAEDRUS: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: Then he will not seriously incline to 'write' his thoughts 'in water' with pen and ink, sowing words which can neither speak for themselves nor teach the truth adequately to others?

PHAEDRUS: No, that is not likely.

SOCRATES: No, that is not likely—in the garden of letters he will sow and plant, but only for the sake of recreation and amusement; he will write them down as memorials to be treasured against the forgetfulness of old age, by himself, or by any other old man who is treading the same path. He will rejoice in beholding their tender growth; and while others are refreshing their souls with banqueting and the like, this will be the pastime in which his days are spent.

PHAEDRUS: A pastime, Socrates, as noble as the other is ignoble, the pastime of a man who can be amused by serious talk, and can discourse merrily about justice and the like.

SOCRATES: True, Phaedrus. But nobler far is the serious pursuit of the dialectician, who, finding a congenial soul, by the help of science sows and plants therein words which are able to help themselves and him who planted them, and are not unfruitful, but have in them a seed which others brought up in different soils render immortal, making the possessors of it happy to the utmost extent of human happiness.

PHAEDRUS: Far nobler, certainly.

SOCRATES: And now, Phaedrus, having agreed upon the premises we may decide about the conclusion.

PHAEDRUS: About what conclusion?

SOCRATES: About Lysias, whom we censured, and his art of writing, and his discourses, and the rhetorical skill or want of skill which was shown in them—these are the questions which we sought to determine, and they brought us to this point. And I think that we are now pretty well informed about the nature of art and its opposite.

PHAEDRUS: Yes, I think with you; but I wish that you would repeat what was said.

SOCRATES: Until a man knows the truth of the several particulars of which he is writing or speaking, and is able to define them as they are, and having defined them again to divide them until they can be no longer divided, and until in like manner he is able to discern the nature of the soul, and discover the different modes of discourse which are adapted to different natures, and to arrange and dispose them in such a way that the simple form of speech may be addressed to the simpler nature, and the complex and composite to the more complex nature—until he has accomplished all this, he will be unable to handle arguments according to rules of art, as far as their nature allows them to be subjected to art, either for the purpose of teaching or persuading;—such is the view which is implied in the whole preceding argument.

PHAEDRUS: Yes, that was our view, certainly.

SOCRATES: Secondly, as to the censure which was passed on the speaking or writing of discourses, and how they might be rightly or wrongly censured—did not our previous argument show—?

PHAEDRUS: Show what?

SOCRATES: That whether Lysias or any other writer that ever was or will be, whether private man or statesman, proposes laws and so becomes the author of a political treatise, fancying that there is any great certainty and clearness in his performance, the fact of his so writing is only a disgrace to him, whatever men may say. For not to know the nature of justice and injustice, and good and evil, and not to be able to distinguish the dream from the reality, cannot in truth be otherwise than disgraceful to him, even though he have the applause of the whole world.

PHAEDRUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: But he who thinks that in the written word there is necessarily much which is not serious, and that neither poetry nor prose, spoken or written, is of any great value, if, like the compositions of the rhapsodes, they are only recited in order to be believed, and not with any view to criticism or instruction; and who thinks that even the best of writings are but a reminiscence of what we know, and that only in principles of justice and goodness and nobility taught and communicated orally for the sake of instruction and graven in the soul, which is the true way of writing, is there clearness and perfection and seriousness, and that such principles are a man's own and his legitimate offspring;—being, in the first place, the word which he finds in his own bosom; secondly, the brethren and descendants and relations of his idea which have been duly implanted by him in the souls of others;—and who cares for them and no others—this is the right sort of man; and you and I, Phaedrus, would pray that we may become like him.

PHAEDRUS: That is most assuredly my desire and prayer.

SOCRATES: And now the play is played out; and of rhetoric enough. Go and tell Lysias that to the fountain and school of the Nymphs we went down, and were bidden by them to convey a message to him and to other composers of speeches—to Homer and other writers of poems, whether set to music or not; and to Solon and others who have composed writings in the form of political discourses which they would term laws—to all of them we are to say that if their compositions are based on knowledge of the truth, and they can defend or prove them, when they are put to the test, by spoken arguments, which leave their writings poor in comparison of them, then they are to be called, not only poets, orators, legislators, but are worthy of a higher name, befitting the serious pursuit of their life.

-- Phaedrus, by Plato, translated by Benjamin Jowett

When considering the question of invention, it is also worth looking at one of the distinctions frequently made between the Mesopotamian writing-system and the Egyptian. It is sometimes argued that, because of the largely mercantile character of Sumerian civilisation and the fact that writing in southern Mesopotamia seems to be linked to accounting techniques and economic purposes, writing in Sumer was primarily a form of 'book-keeping', a convenient tool. On the other hand, runs the argument, Egyptian writing was essentially a royal accomplishment, used to commemorate the achievements of the palace and the status of courtiers and the king's relatives; as such it was ceremonial, designed only to record features which were already well-enough known to the ruling elite. Hieroglyphs, on this view of things, would merely be boasting made permanent. There is really no reason, apart from a spurious neatness, for such a clear-cut distinction. Writing is writing, and once the basic principles are established -- which could take little more than a few months -- the uses to which it may be put are already complex, while the flexibility of the Egyptian writing system, and the way that it fits the language for which it was intended, is such that it could be applied immediately to any useful purpose; the difference, after all, between writing 'the royal tutor Mehy' and 'the royal tutor, two sacks of corn' is not very daunting. A similar point has also been made by Kaplony (1966b, 67 n. 36).

A compromise might be suggested here. Since the Egyptians ascribed the invention of their writing system, not to a king, but to a god, and since they consistently maintained this view later, it may be that Egyptian writing was essentially a temple creation, perhaps even, to pursue the idea, an invention by the priests of Thoth at Ashmunein (Hermopolis in middle Egypt), or one of his other cult-centres. This is tempting, since priests are likely to have had both the leisure and the training for abstract speculation, but it leads us into a difficulty. Temples, at most periods of Egyptian history, were essentially government departments, and the 'Church and State' theory of Egyptian society receives very little support from the surviving documents. Temple officials in the archaic period, and therefore probably in the century or so preceding, seem to have been essentially royal appointees, even princes or royal relatives, and the involvement of the royal court is once again seen to be almost inevitable.

Leaving aside this rather inconclusive line, it is also possible, and more promising, to see the influence of an inventor, or group of inventors, in the way in which the Egyptian writing system is applied so successfully to the Egyptian language. This language, at least in its latest phase, that of Coptic, is comparatively well known, and our knowledge of Coptic, combined with intuitive argument and comparisons with related languages, is the basis for our understanding of the earlier phases, especially Late Egyptian, the vernacular from at least 1500 B.C. and a written form of the language from slightly later. Middle Egyptian, the 'classical' form of the language, has many of the characteristics of an artificial, or at least highly literary idiom, and may never have been spoken in the form in which we have it. Our grasp of this phase is correspondingly less, but even this is markedly greater than our knowledge of archaic Egyptian, such as appears in the Pyramid Texts, the earliest connected body of writing in Egyptian, even though surviving only in copies from the fifth and sixth dynasties (see now Allen 1984). But even in this rather unsatisfactory state of affairs, we do know enough to be able to characterise the Egyptian language and try to place it in its context (see in general Kees 1973, Sethe 1935).

Ancient Egyptian is one of the language-family, widespread in North Africa and the Near East, which is traditionally known as Hamito-Semitic, but now increasingly referred to as Afro-asiatic (Hodge 1971). Within this rather diffuse collection, the best known, and the easiest to define, are the Semitic languages. These are a coherent group which range over the Near East and Ethiopia, and include modern Hebrew and Arabic as well as ancient Babylonian (Akkadian) and the almost extinct Aramaic. The relations between these languages are close, as close, mutatis mutandis, as those between the various Romance languages of Europe, and they are characterised by roots, normally composed of three radical consonants, in which the changes of meaning corresponding to our verbs, nouns or participles are normally expressed by varying the vowels according to fixed rules (there are hardly any 'irregularities' in the sense that most European languages exhibit). There are some prefixes, and a series of terminations corresponding to number, gender, and case endings (frequently obsolescent). The existence of some features common to both the Semitic and the Indo-European families of languages is worth some thought: case-endings, the existence of a dual number alongside singular and plural, certain resemblances in numerals and prepositions, aspects in the verb, and above all grammatical gender, which is absent from the remainder of the world's languages. However, if these two groups are related, it must be at a stage so far distant in time that it is now impossible to chart. The other languages of the Afro-asiatic family are confined to Africa, and are sometimes termed 'Hamitic1, although the differences between these are so much greater than is the case with the Semitic languages that the whole group is really questionable. Egyptian, however, does have some links with several Berber languages, but these are distinctly elusive. The links with the Semitic languages, on the other hand, are clear enough, and have even led some authorities to believe that Egyptian is a Semitic language, with some unusual sound-changes. This is rather far-fetched as it stands. Egyptian has a unique series of palatalised consonants on the one hand, and while it does have one tense, the Stative or misleadingly named 'Old Perfective', its verbal system is largely based on nominal roots, which Callender (1975) has interestingly seen as the various case-endings of a verbal noun with appropriate suffixes. It is a pity that no trace of case-endings survives in Egyptian from any period, since Callender's theory is extremely tempting, and rather informative. But the exact status of Egyptian within the Afro-asiatic family is almost impossible to define. An earlier theory, that Egyptian was a mixed language, rather like modern English, with the Semitic-speaking 'dynastic race' filling the role of the Normans, is grammatically extremely unlikely and historically unnecessary. It may be that Egyptian was merely one of a whole series of languages, or dialects, spoken in the areas of the Sahara and 'Arabian' deserts, which disappeared, or coalesced, with the increasing desiccation of these regions after the last pluvial phase. These may have survived as Beduin languages or dialects well into the historical period, but nothing at all is known of them. Nevertheless, their disappearance was responsible for the apparent isolation of Egyptian which is otherwise so puzzling. (Among the unidentified scripts which have been found in Egypt, one from 'Ain Amur between Kharga and Dakhla is certainly interesting (Fakhry 1940, 764 and PI. 96b. It resembles Egyptian demotic, but is not readable as such. A similar oddity appears on the Colossus of Memnon (Bernand 1960, 213 and PI. 54), but these scripts are too late to be of much help for the present purpose.)

Whatever the exact position of Egyptian as a language, the writing system which came into being with such relative speed was ideally suited to it. The characteristics of the hieroglyphic system have been well described by Sethe (1935) and, more recently, Fischer. In Sumerian, pictures were applied to other concepts, less easy to portray literally, which sounded identical, or perhaps similar (the language as preserved to us shows a remarkable number of homophones). Sumerian is not a Semitic language, and indeed has no known cognates, but Egyptian shared the triconsonantal root system of the Afro-asiatic family. One such root, for example, whose consonants are h-t-r, has been well studied by Ste Fare Garnot. Words involving these three consonants are known from later Egyptian, with meanings such as 'twin', 'tax, imposition', 'necessity' and 'horse'; this is puzzling, and the words may be put down as mere coincidences, until the underlying meaning ('yoke') is realised. Similarly another root, n-f-r, means both 'good' and 'final', which are extended meanings from the same idea, much as 'perfect' comes from Latin perfectus 'finished'. In general, there is a clear tendency for all words from a single root to be written with one pictorial sign, or ideogram, apparently chosen from the range of words available from this root. The vowels are apparently ignored for this purpose. Whether the roots were systematically recognised by the Egyptians or not is debatable, but a tendency to group such words together in the mind must have been almost inevitable. This classification in terms of roots, conscious or unconscious, is probably the real meaning of the so-called 'vowellessness' of the Egyptian script. This is completely different from the Sumerian pattern, where true puns are the basis of the signs chosen, and it seems to involve a much greater abstraction, surprising perhaps at such an early date. The absence of vowels is more striking when applied to a language where changes of vowels indicate major shifts in meaning. It is true that the later Semitic alphabets, such as Hebrew and Arabic, also omit vowels, but these alphabets are probably essentially derived - via the so-called proto-Sinaitic script - from the Egyptian writing system anyway, and the principle may have been kept because it made for a convenient semi-shorthand. One explanation sometimes put forward for the Egyptians' ignoring of vowels is particularly unconvincing: dialects may have existed which used differing vowel patterns, as in later Coptic, but it is difficult to imagine that the vowels were ignored in order to avoid confusion or embarrassment. It is simpler to believe that the very structure of the root-system in Egyptian imposed vowellessness when a picture-system was evolved; in most cases there might be only one possible object portrayable for the whole 'family' of words. Vowels were simply irrelevant, rather than ignored. It is probable that cuneiform would also have been vowelless if Semitic-speaking Mesopotamians had invented it.

In addition to triradical ideograms, there are also a fair number of biradical signs, which appear alongside the triradicals. Some so-called biliterals are probably triliterals in disguise; for example, the words, hmt 'wife' and hmt 'maidservant', which look identical in our transliteration, are written with different ideograms. The reason for this is probably not desire for clarity, as Fischer (1977, 1190) supposes, but the fact that Coptic shows that the word for 'wife', hiome, was formed from a triradical root, hym. (For the reconstruction of such forms see among others Fecht, 1960.)

This system is obviously a clear step towards writing, but it still lacks precision; how is a picture being used in any particular context? The definition is supplied by the other feature of the Egyptian script, the existence of uniconsonantal signs. This is something not found in Mesopotamian writing, and again has the hallmark of being a deliberate invention. A naive view might be to decide that uniconsonantal signs are a later stage of the script's development, derived either from worn-down biliterals or from increasing abstraction and sophistication. But uniconsonantals are present from the beginning, and are used either to 'anchor' the ideograms to specific values and meanings, or to add grammatical or other elements which by definition cannot be present in the ideograms themselves. The origin of these uniconsonantals, or 'alphabetic' signs, is far from clear. The obvious explanation is acrophony - the 'A is for apple' principle, a system which seems to lie behind the proto-Sinaitic script. This is far from convincing, however. More likely is Kaplony's explanation (1966, 1973a) that uniconsonantal signs were derived from, and on occasions could even stand for, words in which the key consonant was the most characteristic, and where the other consonants were weak (semi-vowels or the feminine ending -t, which was regarded as extraneous and which may have ceased to be pronounced at an extremely early date). Thus the hieroglyph 'high ground' (kyt, pronounced something like *kdyat) became k, that for 'cobra' (possibly \v3dyt or *wadjdyai) became dj, and so on. Unfortunately not all uniconsonantal signs can be pinned down in this way, but the idea is certainly suggestive.

The uniconsonantal signs are not merely a remarkable abstraction, but they are also convenient in the extreme. With them the complexity of a pictographic script is cut down to manageable proportions (while 2500 signs exist in the corpus, the beginner can make considerable progress if he knows 250). Since the signs are pictorial, they are much easier to memorise than Mesopotamian signs, which rapidly developed into abstract patterns. The reason why hieroglyphs did not become the standard script of the Near East, rather than the more difficult cuneiform, must be cultural rather than a question of convenience. The 'alphabetic' signs are genuinely such; the attempt by Gelb (1963) to see in them a sort of 'vowelless syllabary' runs contrary to most of what we know about their use.

Archaic hieroglyphs -- for we are now in the first two dynasties -- show almost all the characteristics of the later system (see the convenient tabulation by de Cenival 1982, 61-2); the test of this is that they can, after a certain culture-shock, be read by a student of classical Egyptian. As the system develops, determinatives (signs which are not read, but indicate the class of object to which the word belongs) are introduced more frequently, although they too are present in the system from its inception. This is equally a feature of Mesopotamian writing (although some cuneiform determinatives begin the word, all Egyptian ones end it, and act as a rudimentary form of word-divider). The system of ideograms, displaced ideograms (determinatives), and phonetic signs may sound cumbersome, but it can be mastered fairly quickly and successfully. Certainly when Egyptian is found written in an alphabetic script, as in Hellenistic and Roman texts where the Greek alphabet is applied to the language, the result, perversely enough, is extremely difficult to follow, and the advantages of the native script become clear. This in itself, rather than cliches about Oriental conservatism, helps to explain why the Egyptians never took their alphabetic scheme to what to us would seem to be the obvious conclusion - writing with an alphabet.(The difficulties which even an alphabetic script can entail are shown well by Levine (1964), who republishes an Aramaic ostracon in which every important word has been re-translated; the text then becomes an account of "a dream instead of a discussion about vegetables. This could not happen in hieroglyphs.)

The corpus of archaic inscriptions from Egypt, on cylinder seals, jar-labels, funerary monuments and sherds, has been published by Kaplony (1963 and 1966a). Cursive tendencies are already apparent in ink inscriptions on stone vases, even from the so-called 'Dynasty O'. In the tomb of Hemaka, a high functionary of the reign of king Den (c. 3000 B.C.) there was found a flattened roll of papyrus (Emery 1938, 41; Cerny 1952, 11). Unfortunately it was blank; but papyrus did not remain unused for long, and the civilisation of ancient Egypt was already set on its rare and beautiful course.

16.vii. 1985

University of Cambridge

_______________

References

Allen, J. P. 1984. The inflection of the verb in the Pyramid Texts. Malibu.

Arnett, W. S. 1982. The predynastic origin of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Washington (University Press of America).

Barta, W. 1982. Zur Namenform und zeitlichen Anordnung des Königs "Ro". Göttinger Miszellen 53: 11-13.

Bernand, A. and E. 1960. Les incriptions grecques et latines du colosse de Memnon. Cairo. Callender, J. B. 1975. Middle Egyptian. Malibu.

Cerny, J. 1952. Paper and books in Ancient Egypt. London: University College.

de Cenival, J.-L. 1982. La naissance de l'écriture. In Naissance de l'écriture, Catalogue, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais 7 mai - 9 août 1982, pp. 61-2. Paris.

Emery, W. B. 1938. The Tomb of Hemaka. Cairo.

Fakhry, A. 1940. A Roman temple between Kharga and Dakhla. Annales du Service 40: 763-8.

Fecht, G. 1960. Wortakzent und Silbenstruktur. Glückstadt, Hamburg and New York.

Fischer, H. G. 1977. Hieroglyphen. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie II, pp. 1189-99. Wiesbaden.

Frankfort, H. et al. 1946. The intellectual adventure of Ancient Man. Chicago.

Gelb, I. J. 1963. A study of writing. Revised edn. Chicago.

Hodge, C. T. 1971. Afroasiatic: a survey. The Hague and Paris.

Hoffman, M. A. 1980. Egypt before the Pharaohs. London (Routledge & Kegan Paul).

Kaplony, P. 1963. Die Inschriften der ägyptischen Frühzeit. 3 vols. Wiesbaden.

Kaplony, P. 1966a. Kleine Beiträge zu den Inschriften der ägyptischen Frühzeit. Wiesbaden.

Kaplony, P. 1966b. Strukturprobleme der Hieroglyphenschrift. Chronique d'Egypte 41: 60-99.

Kaplony, P. 1972a. Die Prinzipen der Hieroglyphenschrift. In Textes et langages de l'Egypte pharaonique I, pp. 3-4. Cairo.

Kaplony, P. 1972b. Die ältesten Texte. In op. cit. II, pp. 3-13.

Kees, H. et al. 1973. Ägyptische Schrift und Sprache. Leiden.

Levine, B. A. 1964. Notes on an Aramaic dream text from Egypt. Journal of the American Oriental Society 64: 18-22.

Petrie, W. M. F. 1912. The formation of the alphabet. London (Quaritch).

Ste Fare Garnot, J. 1959. Sur le rôle du vocalisme en ancien égyptien et en copte. Bull, de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientate du Caire 58: 39-47.

Sethe; K. 1903. Beiträge zur ältesten Geschichte Ägyptens. Leipzig.

Sethe, K. 1935. Das hieroglyphische Schriftsystem. Glückstadt and Hamburg.

Shaw, I. M. E. 1984. The Egyptian archaic period: a reappraisal of the C-14 dates (1). Göttinger Miszellen 78: 79-85.