Greek Readers' Digests (Again)? Some Lysianic [x] on P. Oxy. 31.2537

Linda Rocchi

From Defining Authorship, Debating Authenticity: Problems of Authority from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

Edited by Roberta Berardi, Martina Filosa, and Davide Massimo

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

1 Introduction

Over the last two centuries, Egypt has been the scene of a great number of excavations which have enormously increased our knowledge of Greek literature and culture, and Attic oratory makes no exception. What immediately leaps out, however, is that this remarkable season was quite grudging of findings of works of the logographer Lysias, especially considering the number of papyri devoted to the work of the other two 'giants' of Classical Athenian oratory, Isocrates and Demosthenes.1

The copious number of speeches written by the most prolific among the ancient orators seems to have amounted to the astonishing figure of at least 233 orations.2 Nevertheless, during the history of its transmission, this collection suffered severe reductions, to the effect that only 35 of these speeches have survived to the present day.3

The extant Lysianic papyri, despite being only 10, have proven to be a unique source of information on what the corpus of Lysias might have been before it was cut down to what it is today:4 as Obbink (2005) 104 pinpointed, while the Demosthenic and Isocratic papyri preserve, for the vast majority, known speeches of these authors, among the papyri containing the work of Lysias known orations 'are significantly outnumbered by papyri of Lysian speeches that did not survive antiquity'.

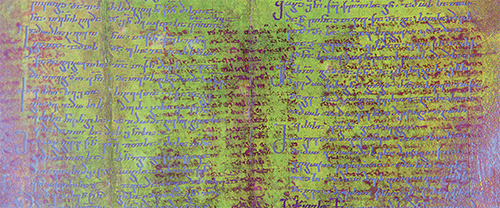

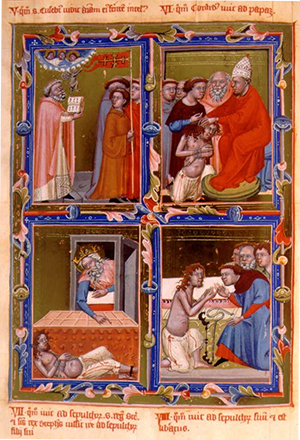

The place of honour among papyri dealing with unknown speeches, at least in terms of numbers, is certainly held by P. Oxy. 31.2537:5 this leaf of papyrus codex, dated palaeographically to the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd century AD, contains the [x] of at least 18 Lysianic speeches which were previously unknown to us -- or known just from the title and small quotations in lexicographers -- plus the summaries of four other speeches6 preserved in Pal. gr. 88 as well, for a remarkable total of 22 items.

The aim of the present article, which is part of the work done on the original papyrus over a six-month period at the University of Reading, will be that of analyzing some relevant passages in order to make some inferences on the original purpose and readership of this document. We will seek, firstly, to understand how these summaries were composed, with the purpose of narrowing down the kind of information in which the compiler -- and thus his public -- appeared to be more interested. Secondly, through a comparison of the differences and similarities between this set of summary and other ancient works labelled as such, this study will attempt to put P. Oxy. 31.2537 in its right position within the broader category of the [x] as a (sub)literary genre.7

In the hope of having achieved a satisfactory result, it might be worth highlighting the only certain and fundamental point in this discussion: whatever the exact original purpose of this peculiar list of summaries was, neither the permanent loss of the rest of the codex, nor the dramatically damaged state of the only surviving leaf of this manuscript had been able to obliterate the fact that, from 5th-century Athens to the Graeco-Roman Egypt, the interest in the text of Lysias, the brilliant metic logographer [In anc. Gr. lit., a prose-writer; especially, a historian; a chronicler; one who writes history in a condensed manner with short simple sentences.] that more than any other orator had been capable of portraying the everyday life of his adoptive country, was alive and well. And, judging from the substantial amount of speeches summarized in this papyrus which did not make it to the Mediaeval tradition, even more prosperous and flourishing than it was ever going to be in the centuries to come.

2 The Papyrus

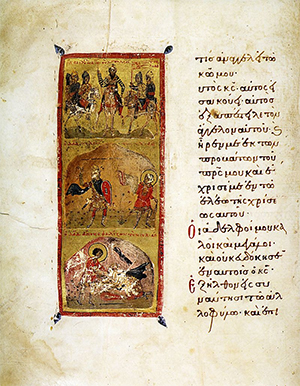

Before briefly exploring the contents of this papyrus, it appears necessary to say a few words on the material state of this document. The codex from which P. Oxy. 31.2537 derives was compiled by a clearly experienced hand in what Turner/Parsons ([1987] 22) define 'formal mixed'.8 This means that whoever commissioned the manuscript was able to pay a professional scribe to produce it. The papyrus is written both on the recto [the side of a leaf (as of a manuscript) that is to be read first; a right-hand page] and on the verso [the side of a leaf (as of a manuscript) that is to be read second; a left-hand page], as is normally expected for a codex, and is 24.5 cm in height and 9.5 cm in breadth, 'with margins of c. 0.5 cm at the top and c. 2 cm at the bottom' (Rea [1966] 23).

The recto is comparatively in better conditions than the verso, but the original number of lines -- 48 on the recto and 45 on the verso -- is preserved on both sides. The break which runs down the margin appears too clear to suggest that there was more than one column per page (cf. Rea (1966] 23), and although the possibility cannot be completely discarded, it should be noted that a format with two columns on each page 'is used somewhat rarely in papyrus codices' (Turner [1977] 35), and is on the contrary more commonly employed in parchment ones. Moreover, if the smudged spot of ink on the top margin of the verso is to be interpreted as a trace of a page number (cf. Rea [1966] 23), it is worth bearing in mind that the top centre of the page was a preferred position for this kind of information (cf. Turner/Parsons (1987] 16): if there had been another column, the page number would have probably been between the two columns, and it would have been now completely devoured by the wide lacuna on the top margin of the page.

3 The Contents

These 22 Lysianic summaries are divided into seven sections according to the legal procedure,9 and are grouped together regardless of the supposed authenticity of the speech: the first section, which realistically started in the now lost previous page and was probably concerned with trials [x], 'for violence', contained at least two speeches, while the second section deals with four speeches of the [x] type, 'for slander', none of which is indisputably attributed to Lysias. The third subdivision, devoted to five speeches [x]. 'for ejection', occupies the bottom section of the recto and the top one of the verso, and is followed by two speeches whose typology is unknown, but which possibly represent cases of [x], 'exchange of properties'. The two following sections encompass, respectively, five speeches [x], 'for deposit', and three ~[x], 'for usurpation of civic rights', while the last one contained seven speeches of unknown type, of which only one is partially readable at the end of the verso.

Despite its fragmentary state, then, it is clear that P. Oxy. 31.2537 presents many features of interest. As was briefly mentioned above, this papyrus contains the summaries of many speeches that, although evidently still circulating in 2nd century Egypt, were previously unknown to us, or only partially known by the title or brief quotations in ancient lexica. What is particularly interesting, however, is that among the material presented in this papyrus -- both known and unknown speeches -- there are several orations whose authorship is uncertain.

4 Some Instructive Examples

One subdivision in particular can help to illustrate the compiler's modus operandi in arranging the material, and to gather information on his summarizing style: the section containing speeches on slander (II. 6-29 recto). This section encompasses four speeches: two speeches [x], summarized together (II. 6-15), the speech [x] (II. 16-22), and the speech [x] (II. 23-29). These four speeches appear together also in Pal. gr. 88, but in the reverse order.10

Let us first consider the summary of the two speeches [x] (Lys. 10-11), As was only briefly touched upon earlier, this [x] is, strictly speaking, a Doppel-[x], dealing both with Lys. 10 and Lys. 11 as two distinct Lysianic speeches.11 Scholars generally agree in considering Lys. 11 the epitome of Lys. 10: 12 Harpocration himself seems to be aware of the existence of the longer version of the speech only,13 and he does not even regard it without suspicion as an authentic Lysianic work.14 It might also be noted, in passing, that the fact that both the speeches are included in this set of summaries indicates the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd century AD as the terminus ante quem [GT: term before he] for the undue inclusion of Lys. 11 in the corpus.15

The speech [x] (Lys. 9) is quoted once by Harpocration with the indication [x]16 and, although it is the second item in a series of orations under a heading that specifically reads as [x], it shines through the whole speech that this trial does not deal with a [x] at all.17

Similarly, the inclusion of the speech [x] 18 (Lys. 8) among the [x] is, as with Lys. 9, primarily a matter of vague thematic affinity.19 The oration is defined by Todd (2007) 541 'the oddest of the speeches in the corpus of Lysias, and possibly of any Attic Orator', not least because it does not appear to be a forensic speech at all, it is not likely to have been written by Lysias, and there are even solid reasons to doubt that it was written during Lysias' lifetime. Accordingly, then, the oration is never mentioned by Harpocration.

Valerius Harpocration, was a Greek grammarian of Alexandria, probably working in the 2nd century AD. He is possibly the Harpocration mentioned by Julius Capitolinus (Life of Verus, 2) as the Greek tutor of Lucius Verus (2nd century AD); some authorities place him much later, on the ground that he borrowed from Athenaeus.

Harpocration's Lexicon of the Ten Orators, which has come down to us in an incomplete form, contains, in more or less alphabetical order, notes on well-known events and persons mentioned by the orators, and explanations of legal and commercial expressions. As nearly all the lexicons [dictionaries] to the Greek orators have been lost, Harpocration's work is especially valuable. Amongst his authorities were the writers of Atthides (histories of Attica), the grammarian Didymus Chalcenterus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and the lexicographer Dionysius, son of Tryphon. The book also contains contributions to the history of Attic oratory and Greek literature generally.

The Collection of Florid Expressions, a sort of anthology or chrestomathy [a collection of selected literary passages (usually from a single author); a selection of literary passages from a foreign language assembled for studying the language; or a text in various languages, used especially as an aid in learning a subject.] attributed to him by the Suda, is lost, but elements of it survive in later lexica. A series of articles in the margin of a Cambridge manuscript of the Lexicon forms the basis of the Lexicon rhetoricum Cantabrigiense by Peter Paul Dobree.

-- Harpocration, by Wikipedia

Another speech, [x] (II. 8-11 verso), the fifth and last speech in the section devoted to [x], is also regarded as dubious by Harpocration.20 Moreover, if the supplement [x], tentatively put forward by Rea (1966) 37 and highly consistent with the traces on the papyrus, is accepted in I. 43 verso, there would be here yet another oration of unknown legal typology on whose paternity Harpocration ([x] 25 K.) was unsure.

As for the other speeches, either they are so fragmentary that it is not possible to link them to any (partially) known speech, or, when the title is readable, the speech does not seem to be mentioned by Harpocration at all. At this point it should be sufficiently clear that the papyrus features many speeches on which Harpocration was, at best, suspicious. The presence of these speeches, and of several new ones, raises questions not only on the substance of this manuscript when it was still intact, but also -- and perhaps more interestingly -- on the real nature of this papyrus and the purpose for which it was originally compiled.

The first impression is that the compiler is clearly not making a selection: the presence of new and dubious speeches suggests that he was not aware of -- or simply not interested in -- matters of authenticity. It seems, on the contrary, that he was compiling a list, some sort of annotated catalogue of all the speeches by Lysias which were available at his time.

The impression is reinforced by the presence, on II. 24-28 verso, of a [x]. The existence of a Lysianic speech homonymous [having the same name.] to Isocr. 17 is assured by Photius (a 2030 Th.), who quotes, in this respect, the verb [x], which does not appear anywhere in the Isocratic text.21 Whether there existed two different speeches -- one by Lysias and one by Isocrates22 -- written for the two parties in the same lawsuit, or not, is perhaps open to question, although enough evidence that this had actually been the case has been put forward quite conclusively by Trevett (1990). What matters most for the present purpose is that, since -- as will be further explored -- there does not seem to be any kind of critical approach from the part of the epitomizer [One who abridges or summarizes; a writer of an epitome.], it appears safe to assume that he had a [x], clearly labelled as the work of Lysias, available, and included it, as it seems, without questions. Furthermore, the impression that the compiler was indeed making a list appears to be encouraged also by the format of the document: the papyrus is organized in seven different sections, and each one is labelled under a heading, clearly stating the legal charge and the number of speeches summarized in each group.23 Evidently, therefore, this feature adds up to the others and inevitably makes this catalogue look even more like a list.

There is, however, another criterion that should be taken into account in analyzing the original purpose of this manuscript: the style. As a matter of fact, the way in which this papyrus is written and organized, and the decisions the compiler made on the kind of information that should have been included and the one that should have been left out, sharply distinguish this papyrus from any other work containing summaries of speeches. There are, indeed, quite a few other ancient documents, characterized as [x], related to rhetorical works, which ought to be analyzed to evaluate differences and similarities between them, and to consider whether P. Oxy. 31.2537 fully fits in this category or not. In her 1998 book, Van Rossum-Steenbeek analyzed a selection of ancient summaries, comparable under many aspects to the ones in P. Oxy. 31.2537, and came to the conclusion that the [x] she surveyed were meant to be read along with, and not instead of, the original texts. However, the possibility that the list of summaries contained in P. Oxy. 31.2537 was actually meant to function as a Greek Readers' Digest, thus sparing the ancient reader the struggle of reading the torrential work Lysias in its full-length version, cannot be completely discarded.

Strictly speaking, the first known [x] to a Lysianic speech is to be found in Dionysius of Halicarnassus' critical work on the orator,24 where the argument to the speech is given prior to the actual text of the oration 'to make it clear whether [Lysias] employed a proper and pertinent opening'.25 Perhaps even more significant for the present study -- due to the fact that they are, as P. Oxy. 31.2537, original ancient documents -- are the [x] to Dem. 21 in P. Lond. lit. 179 (1st-2nd century AD), which Gibson (2002) 201 aptly defines as 'a rhetorical prologue and commentary' which shows 'predominantly rhetorical interests",26 and the two[x] to Isocr. 1 and 2 placed before their respective speeches in P. Kell. 3 gr. 95 (4th century AD), probably the work of a schoolteacher,27 which "offer simplistic summaries of the speeches that would serve nicely as brief introductions to the speeches for early readers' (McNamee [2001] 907-8). Other later [x] are the ones put together by Libanius in the 4th century AD, whose 'scholarly and pedagogical agenda' (Gibson [1999]172) is clear, given the fact that the rhetorician himself describes his work as a preparatory reading, i.e. an introduction to Demosthenes' speeches; the [x] to Isocrates found in the extant Mediaeval manuscripts and ascribed to Zosimus (5th-6th century AD), whose context is plainly scholastic and introductory; and the ones in the Mediaeval tradition of Demosthenes28 and Isaeus, clear products of rhetorical schools, as the insistence on Hermagoras' stasis theory goes to show.29

Stasis-theory seeks to classify rhetorical problems (declamation forensic and deliberative situations) according to the underlying dispute that each involves.1 Such a classification is of interest to the practising rhetor, since it may help him identify an appropriate argumentative strategy; for example, patterns of argument appropriate to a question of fact (did the defendant do what is alleged?) may be irrelevant in an evaluative dispute (was the defendant justified in doing that?).

Ancient rhetoricians did not always agree on how to classify a given problem. Consider the case of the adulterous eunuch. A husband may kill an adulterer in the act; a man finds a eunuch in bed with his wife and kills him; he is charged with homicide. According to Hermogenes, the stasis is definition: the facts are agreed, and the dispute is about how to categorise those facts.2 Whatever the eunuch was up to, it was clearly not a fully-fledged instance of adultery; it (and indeed he) lacked something arguably essential to that crime. Is this 'incomplete' adultery nevertheless to be classed as adultery? If so, then the killing is covered by the law on adultery; if not, the killing is unlawful. But the case could also be interpreted as counterplea (antilepsis).3 Counterplea is a form of the stasis of quality, in which the defence maintains that the act for which it is charged is lawful in itself. For example: a rhetor's encomium on death is followed by a rash of suicides; he is charged with crimes against the public interest (demosia adikemata), and defends himself by arguing that he broke no law in practising his profession.4 On this analysis of the adulterous eunuch, the husband's appeal to the law of adultery is seen as determining the stasis as counterplea without further ado.

Disagreement over the classification of a rhetorical problem raises the question of how stasis is in general to be ascertained. According to Hermogenes, one must inspect the krinomenon: if that is unclear, the stasis is conjecture (36.8-9); if it is clear but incomplete, the stasis is definition (37.1-2); if it is complete, the stasis is quality (37.14-15), which in turn has manifold subdivisions. However, Hermogenes does not tell us what the krinomenon is or how one identifies it. The krinomenon also figures in the alternative analysis of the adulterous eunuch, where it is linked to two other concepts, aition and sunekhon, which make no appearance in Hermogenes. We know that the triad aition-sunekhon-krinomenon goes back to Hermagoras (fr. 18 Matthes); but the significance of the terms in his system is uncertain,5 and (as we shall see) in subsequent sources they are used in strikingly inconsistent ways. This paper attempts to trace the history of these and related terms, and conceptions of the fundamentals of stasis-theory from Hermagoras on.

_______________

Notes:

1 For an overview of stasis-theory see D. Russell, Greek Declamation (Cambridge, 1983), 40-73; G. Kennedy, Greek Rhetoric under Christian Emperors (Princeton, 1983), 73-86; L. Calboli Montefusco, La dottrina degli status nella retorica greca e romana (Hildesheim, 1986); and my commentary on Hermogenes [x] (Oxford, forthcoming).

2 See Hermogenes 60.19-61.3 Rabe. This case is found also in Sen. Contr. 1.2.23. A simpler variant in which the eunuch is prosecuted for adultery (RG 5.158.12-15, 7.217.21-4; Syrianus II 114.1 Rabe) is evidently definition.

3 See RG 5.158.8-159.6 Walz.

4 See RG 8.407.14-16; the same case with a philosopher is found in Fortunatianus, RLM 92.26-9 Halm.

5 See D. Matthes, 'Hermagoras von Temnos', Lustrum 3 (1958), 58-214, esp. 166-78 (with references to earlier literature). More recently: K. Barwick, 'Augustinus Schrift De Rhetorica und Hermagoras von Temnos', Philologus 105 (1961), 97-110; id., 'Zur Erklarung und Geschichte der Staseislehre des Hermagoras von Temnos', Philologus 108 (1964), 80-101; id. 'Probleme in den Rhet. LL Ciceros und der Rhetorik des sogenannten Auctor ad Herennium', Philologus 109 (1965), 57-74; J. Adamietz, M. F. Quintiliani Institutionis Oratoriae Liber III (Studia et Testimonia Antiqua 2, Munich, 1966), 206-21; L. Calboli Montefusco, 'La dottrina del KPINOMENON', Athenaeum 50 (1972), 276-93.

-- The Substructure of Stasis-Theory from Hermagoras to Hermogenes, by Malcolm Heath, The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 1 (1994), pp. 114-129, 1994

What all these texts -- slightly different in length,30 predominant interest, and target readership -- have in common is, without exception, their subsidiary nature in relation to the original text and a didactic tone which are, in more than one occasion, undoubtedly patent [patents: archaic: accessible, exposed]: two shared features that, despite the homogeneity shining through these sources, do not seem to be constitutive parts of P. Oxy. 31.2537 as well. In this document, in fact, there is nothing to suggest that a subsequent reading of the actual speeches was encouraged by this set of [x]: it does not seem to serve as an introduction which aims at a better understanding of the Lysianic text, and no pedagogical or explanatory purpose can be envisaged. As a matter of fact, they appear to be a product concluded in itself, created to give a thorough, clear, and succinct overview of Lysias' (presumed) production, with no other aim but completeness.

Once again, the section devoted to speeches on slander (II. 6-29 recto) can help to illustrate this point.

The summary of Lys. 8 (II. 23-29) is the least useful to the purpose of the present study, and this is mainly due to the poor conditions of the papyrus in this section. This is particularly unfortunate, since the compiler's approach to such difficult a text would have given us further hints on his working principles. Nevertheless, a few useful clues still manage to emerge. First, the scribe or his source evidently recognized the [x] as a key aspect of this controversy: Rea's (1966) 27 suggestion [x] at I. 24 seems, indeed, the only possible reading of the traces. Second, as was already noted by the editor princeps Rea (1966) 30, 'it is clear that the hypothesis states the situation in the most general terms and makes no attempt to explain the very tangled transactions which made the speaker resign from his club': no personal names -- which, contrariwise, abound in the second part of the speech -- seem to be stated, and there is no mention of the pledging of the horse, which was a quite decisive aspect in the speaker's gradual epiphany of his associates' dishonesty. As is seems, then, the compiler is trying to keep it simple and straight to the main issue: the speaker was slandered by his companions [x who apparently said that he was associating with them against their will ([x] at I. 26).31

The [x] of Lys. 9 (II. 16-22), the speech on behalf of the soldier, which is, to some extent, vague and necessarily poor in details, deserves nevertheless our attention by virtue of some intriguing and yet overlooked aspects. First of all, together with the [x] of the speeches [x] (II. 6-15), these seven lines form part of the best-preserved portion of the papyrus. Secondarily -- and more importantly -- this [x] is entirely concerned with the narration of the events, that indeed seems to have been, in light of what is possible to infer from the extant text, the chief concern throughout the whole papyrus. This favourable concurrence of events adds to the fact that the [x] at issue deals with an extant speech, making it possible to outline, on the one hand, the relationship between the summary and its respective speech, and on the other hand, the compiler's synthesizing techniques. Gathering this kind of information on a fragmentary text is extremely useful precisely because, although the results are thoroughly verifiable only in uncommon occasions such as the present one, the general recognizable guidelines can reasonably be extended to the rest of the text as well.32

What clearly emerges from the analysis of this summary is that, although precise verbal coincidences33 suggest that the compiler was working with a text of the speech which was, if not identical, at least closely related to the one that represented the origin of the existing Mediaeval tradition, there was at least one attempt to provide the reader with a slightly reworked version, whose main purpose was probably to make explicit aspects of the plot which were implicit in the narrative of the original speech.34 Evidence of this way of proceeding can be easily tracked down in the very first line of the [x], where the compiler makes clear that the speaker had just got back from a previous military expedition: this detail, central to the understanding of the soldier's rash reaction towards the magistrates, is never specifically stated in the speech, but it is, without much effort, deducible from the narrative. This seems to suggest that the compiler, albeit not interested in matters of authorship and authenticity, at least wanted to get the story straight.

It could be argued, at this point, that the scribe might have tried to make patent some details of the narrative as a way of helping the reader during the examination of the actual speech. But the details he underlines, as was said, are easily evincible [to display clearly: reveal]: he never adds new information. Although, admittedly, the compiler's remarks could help the reader reach a better understanding of the text of the orations, this appears to be more of a side effect than the chief purpose: the scribe's primary concern is not much to clarify the text, but rather to relate plainly the contents of the speeches in what appears to be a literary product conceived as a means of knowing what is in the speech without actually reading it.

Another possible clue which might corroborate this impression -- that of a compiler who sometimes deduces details from the speeches and inserts them in his own narrative to make it flow more smoothly and concisely -- could be glimpsed through a confusion on personal names in I. 17, the first of this summary, where the speaker, Polyaenus, is identified as Callicrates. This confusion, for once, could be not entirely the compiler's fault, but rather arise from an abstruse remark in Lys. 9.5, where the speaker informs the jury that the magistrates apparently threatened to imprison him, [x], 'saying that "Polyaenus has been in town for no less time then Callicrates"'.35 As it is, the sentence admittedly makes little sense and is undeniably easy to misunderstand: what the speaker is clumsily trying to say is that the magistrates found his complaints meaningless, because Callicrates, presumably a fellow-conscript, had been residing in the city after his last campaign for the same -- or even a shorter -- period of time as the speaker, Polyaenus.36 Evidently the compiler, while trying to extrapolate from the text the defendant's name in order to set it out in front of the wondering reader, jumped to the wrong conclusion.37

The summary of Lys. 10-11 (II. 6-15) -- which is the longest in the preserved section of this codex38 -- represents one of the most interesting sections of P. Oxy. 31.2537. The compiler, after a brief statement on the only relevant event,39 devoted the longer section of this [x] to highlighting the only notable discrepancy between the two speeches at issue. Half of this summary (II. 10-15) is indeed solely committed to the mention of the difference between father's and son's ages in the two speeches: in the first one, at the moment of his father's death the speaker was 13 years old and the father 67,40 whereas in the second one, the speaker was 12 and the father 70.41 None of Lysias' client's refutation of Theomnestus' argument and none of his rather detailed remarks on legal terminology (cf. §§16-19) -- which probably played a central role in his rebuttal -- has made it to the [x] of this speech. Nonetheless, this dearth of information does not feel particularly striking if the nature of the text provided by this papyrus is taken into account: even a brisk reading goes to show that this document is not primarily concerned with any kind of 'rhetorical analysis' (Rea [1966] 25), but rather it aims to underline the main elements of the plot, in order to help the reader understand the gist of the trial.

In light of what has been said, it might appear surprising that, in this instance, there appears to be an attempt to depart from the nitty-gritty of the situation and give some sort of comment on a detail in the text of the speeches. It should be noted, however, that this remark is connected to a discrepancy relevant not much in itself, as a textual feature separate from the recounted facts, but rather in its implications for the content of the speeches, namely the chronological frame enclosing the events. Moreover, the fact that the ages do not match in the two speeches (II. 12- 13 [x]) represents indeed the only difference between them, at least when considering the plot: this detail, then, could have been used as a sort of identifying mark to tell the speeches apart -- or even as a kind of 'trivia' information.

5 Further Evidence: The Speeches For Euthynus against Nicias (II. 18-24 verso)

The idea of a compiler chiefly interested in the narrative plot of the speeches, strongly suggested by the style of the summaries thus far examined, seems to be supported also by a very interesting parallel: that between the double [x] of the speeches [x] (II. 18-24 verso) and the summary of Isocr. 21, the speech [x], found in Stephanus Skylitzes' 12th-century commentary on Aristotle's Rhetoric.42

As was probably the case with the [x],43 Lysias and Isocrates had acted as logographers44 for the two opposing parties in the same lawsuit -- Lysias for the defence and Isocrates for the prosecution. It is quite obvious, then, that the background story is the same for both speeches, as is confirmed also by the fact that Rea (1966) 36 was able to supplement the first three lines of the Lysianic [x] on the basis of Isocr. 21. This summary, as usual, does not strive to collect details useful for a rhetorical analysis of the text, but rather to relate plainly and straightforwardly the salient elements of this litigation. Interestingly, it seems possible that the last part of the [x] was devoted, as in the double [x] in II. 6-15 recto, to the mention of the most notable -- at least to the compiler's mind -- differences between the two speeches summarized here. Indeed, in I. 22 there seems to be a reference to the fact that in one of the speeches the orator, possibly Euthynus,45 spoke ill of Isocrates46 ([x]):47 once again, a nice 'fun fact' about the speech at issue. Leaving aside the implications of this remark on Isocrates, which would deserve a specific discussion of its own,48 it is important to notice, here, that the summarizing techniques employed by the compiler of P. Oxy. 31.2537 seem to share some revealing similarities with the summary of Isocr. 21 put together by Stephanus.

While commenting on a passage in Arist. Rh. 1392 b 14-15, a section embedded within a discussion on possible and impossible used in arguments from probability,49 Stephanus offers a brief summary of Isocrates' Against Euthynus50 to explain Aristotle's use of a quotation from this speech.51 Stephanus' summary, like the ones featured in our papyrus, is quite clearly mainly focused on the actual events from which the trial arose. Now, since Stephanus is commenting on Aristotle, and not on Isocrates, his summary of the speech probably did not aim to encourage or make easier a further reading of the Isocratic speech: its purpose was just that of giving to the reader an idea of the contents of the speech, without actually having to read it, to understand what Aristotle was talking about.

The fact that the information, the wording, and the structure of Stephanus' summary are quite similar to the ones presented by the summary of the Lysianic speech encompassed in these lines could represent further evidence for the fact that the list of [x] compiled here might be a sort of annotated catalogue, whose purpose was the same as Stephanus' summary: make the reader aware of the contents while saving him the struggle of reading the original work, just like the modern Readers' Digest.

6 Conclusions

When it was still intact, P. Oxy. 31.2537 must have been a truly remarkable document. As a matter of fact, when one considers that only one leaf of that codex, retrieved by chance from a rubbish heap in Egypt, has handed down to posterity the plot of 22 speeches by Lysias,18 of which were previously unknown, it seems quite likely that almost all the other pages had been equally rich in new information on the work of the logographer.52

But 'quantity' does not necessarily mean 'quality', and the fact that the compiler of P. Oxy. 31.2537 does not seem concerned with '[x]-related' problems has been repeatedly pinpointed during the examination of this material: at least four [x], and potentially even more, were not furnished with Harpocration's seal of approval, and were nonetheless featured in this collection.

Rea (1966) 24-25 rightly pointed out that there is a possibility for Harpocration to have been in Oxyrhynchus during the rule of Marcus Aurelius. It is also likely that, along with his host, Valerius Pollio, and his host's son, Valerius Diodorus, the lexicographer had been part of a coterie of intellectuals with a strong interest in Attic oratory53 which revolved around the middle-Egyptian region. The presence of this 'centre for oratorical studies' right in 2nd-century Oxyrhynchus could lead the reader into thinking that there could have been a link between that group of scholars and the set of [x] collected in P. Oxy. 31.2537. This, however, does not seem to be the case. As Turner (1952) 92 clarifies, in fact, 'for their work such persons would not be content with less than the best available texts of Classical authors', and the summaries presented in this papyrus not only do not seem to fit in this description themselves, but also appear to be derived from a collection of Lysianic speeches which had nothing to do with the erudite discussions on authenticity that were realistically going on in Valerius Pollio's house.

Valeri Pollio (in Latin Valerius Pollio) was a Greek philosopher of the School of Alexandria.

He lived in the time of the emperor Hadrian and was the father of the philosopher Diodorus of Alexandria. It appears mentioned in the Suides as Πωλίων.

-- Valeri Pollio, by Wikipedia

Moreover, along with the fact that the compiler of these [x] seems completely oblivious of questions of authorship, he also appears to neglect any kind of rhetorical analysis of the speech at issue. This lack of interest is particularly intriguing precisely because, on the contrary, a rhetorical examination of the key aspects of the speeches manifests itself as a prominent feature of other known summaries of rhetorical material: for instance, Libanius' [x] to the speeches of Demosthenes, put together for 'the elderly and ill-fated proconsul of Constantinople, Lucius Caelius Montius' (Gibson (1999] 173) around 352 AD, and the summaries found in the Mediaeval manuscripts of the works of Isocrates, Isaeus, and Demosthenes all appear to be introductory works, clear products of the rhetorical school, and influenced deeply by the rhetorical stasis theory outlined by Hermagoras (mid-2nd century BC). It could be argued that perhaps the [x] as a genre developed over time, and that the summaries contained in P. Oxy. 31.2537, being older than the ones just mentioned, were also, in a way, more rudimentary. Nevertheless, to undermine this assumption it is sufficient to examine P. Lond. lit. 179, a papyrus dated to the end of the 1st or the beginning of the 2nd century AD which contains the summary of the Dem. 21 and shows interests similar to the one presented by the later [x] mentioned above. P. Kell. 3 gr. 95 (4th century AD) is, under many aspects, similar to P. Oxy. 31.2537, and seems to have been produced in a school context, a fact that could suggest a similar context for our papyrus as well. Nevertheless, despite its similarities with P. Oxy. 31.2537 -- namely, the codex-format and the brevity of the summaries -- P. Kell. 3 gr. 95 is remarkably different precisely in those characteristics which make it more likely to be a school text aimed at encouraging a subsequent reading of the speeches it summarizes: the [x] are followed by the original speeches, and the speeches themselves are accompanied by some simple marginal comments.54 Moreover, P. Kell. 3 gr. 95 seems to share with the other documents containing [x] a subsidiary nature in relation to the original text and a patent pedagogical intention: two features that, as was highlighted above, do not seem to be sought for by the compiler of P. Oxy. 31.2537. 55

The only elements that appear to interest him, in fact, are the ones connected to the plot, the relation of the events relevant to the trial: once again, the section on [x] has been particularly helpful in understanding this point, mainly because the conclusions drawn on the summarizing method of the compiler had been positively verified on the original version of the text -- or at least a version that was really close to the text as it was transmitted thanks to Pal. gr. 88 56 -- and consequently applied more in general to the remaining [x].

The impression that the compiler was particularly keen on relating, plainly and simply, only the facts relevant to the trial seems supported by the fact that even in the (very few) instances in which some sort of departure from the heart of the matter can be detected, the information provided could be explained as a sort of curiosity, a 'fun fact' that manifests itself as the most notable aspect of the situation. Interestingly, these remarks appear precisely in the two couples of 'double-[x]' featured in this collection: on the one hand, the discrepancy in the ages of father and son in the two speeches [x] (II. 11-16 recto), which represents, in practice, the only real difference between the two (at least with regard to the plot); on the other hand, in the speech [x] (II. 18- 23 verso), the curious remark that someone apparently spoke ill of Isocrates the speechwriter (II. 22-23 verso). These details, then, could easily be explained as a service to the reader to distinguish between two speeches which dealt with the exact same situation.

However, once the structure of these summaries has been examined and a subsidiary or introductory nature in relation to the full-length versions of the speeches is ruled out, a central question, that of the original purpose and destination of this collection of summaries, is still left unanswered. If the aim that Van Rossum-Steenbeek (1998) 161 identified for the selection of [x] she analyzed was, consistently, that of accompanying, clarifying, and commenting on the texts they were related to, but P. Oxy. 31.2537 does not fit in this category, in which category does it fit instead?

The short and honest answer to this question is, of course, that it is impossible to know for sure. What is possible, however, is to try nonetheless and sift through some tentative suggestions. One of the most striking aspects that comes to mind, while considering P. Oxy. 31.2537, is undoubtedly its relative similarity with the inventories of books on papyri analyzed by Puglia (2013) which, in fact, 'sono quasi sempre modesti e semplici' [GT: 'I am almost always modest and simple'], and reveal 'scopi per lo piu pratici e non filologici' [GT: 'scope for the most practical and non-philological'] (p. 4), just like the [x] collected on P. Oxy. 31.2537. Moreover, although many of them appear to have been produced for private use, thus presenting a slapdash format which has nothing to do with the neat arranging of the material on P. Oxy. 31.2537, there are nevertheless some notable exceptions such as, for instance, P. Ross. Georg. 1.22, which is written more roughly but, as our document, appears to be featured on a piece of papyrus that was not re-used, but was meant exactly for the purpose of compiling these inventories.57 The idea of an inventorial destination for P. Oxy. 31.2537 could indeed be fitting, also because the compiler, as was said, does not appear to be making a selection, but rather a list of all the putative works of Lysias at his disposal, since he includes a great deal of items regardless of their authenticity (cf. above). As Canfora (1995) 166 emphasizes, for the speeches of the Attic Orators 'non c'era stata [ ... ] la determinazione [ ... ] di un testo "ufficiale"' [GT: 'Not there had been [...] the determination [...] of an "official" text '], and the fact that in 2nd-century Egypt there could have been corpora of Lysianic speeches resembling what Dover (1968) 2 denominates 'Corpus G', i.e. the collection of works on which Pol. gr. 88 was drawn -- or indeed the elusive 'Corpus A', the (alleged) opera omnia of the metic logographer58 -- is indeed quite likely, and it does not seem improbable that, at some point, there might have arisen a need or a desire to catalogue that astonishing amount of material. This was probably being circulated in single collections of speeches arranged thematically around the same legal issues, a mode of circulation that would be mirrored in the subdivisions in which this papyrus is organized.59 Nevertheless, if this is really the case, it would seem improbable that such a huge number of speeches of Lysias could be contained in one single private library. Judging from this, and from the relative elegance of the format of P. Oxy. 31.2537, this leaf of papyrus codex could perhaps be seen as part of the catalogue of a public library, such as P. Oxy. 27.2456, 27.2462, 33.2659, and 35.2739. 60 We should note, however, that these catalogues were generally written on rolls, and were mostly arranged in alphabetical order.61 Moreover, none of them presents [x] attached to the titles mentioned.

Other interpretations are equally possible. If P. Oxy. 31.2537 were indeed some sort of annotated catalogue, as the same structure of the headings could suggest, there might not be the need to think of the inventory of a library, public or private, but rather of the catalogue of a bookseller, whose business interests highly advised against a clear-cut distinction between [x] and not-so-[x] works of a given author. In this case, the short summary of the speech, with -- when convenient -- an indication of the 'fun facts' about it, would have served as a sort of 'teaser trailer' of the oration, compiled in order to intrigue the potential reader -- and lead him to buy a copy of the work at issue. The very neat handwriting and arrangement of the material, however, which are in sharp contrast with other documents that have been identified as catalogues of booksellers,62 seems to discourage this hypothesis.

Lastly, another possibility has to be taken into account. As it has been tried to pinpoint, the main purpose of these brief summaries seems to have been that of providing the reader with 'condensed versions of texts', and no ancillary relationship with the original speech can be detected. If the most accurate definition of a Readers' Digest is that of 'a digested collection of information consisting of [ ... ] material derived from or based on earlier writings, which is meant to be read for its own sake' (Van Rossum-Steenbeek [1998]161), it might not be desperately unconceivable that these [x], unlike the ones analyzed by Van Rossum-Steenbeek, could, all things considered, fall quite nicely under that definition. The very format of this document -- the codex, much more manoeuvrable and 'user-friendly' than the roll -- seems to characterize the ideal reader for P. Oxy. 31.2537 as someone who does not wish to read this work continuously, but rather to browse quickly through its contents and locate easily the item they are looking for. If this latter hypothesis is true, then the readership P. Oxy. 31.2537 was directed to (or commissioned by) was perhaps represented by that fancy (but perhaps not always erudite) upper class of the Oxyrhynchus region, which sometimes could have been, as often happens today, too busy -- or perhaps too lazy -- to read the entire monstrous bulk of the works of Lysias, but still had the desire to make a good impression and strike their equally rich, and possibly much more learned, friends as profound connoisseurs of the speeches of the famous logographer. Provided, ca va sans dire [GT: it goes without saying], that no-one decided to ask too much.

7 Appendix: Texts

col. 1 recto, II. 6-29

[x]

col. 2 verso II. 18-28

[x]

col. 2 verso II. 42-45

[x]