A Juridical Fabrication of Early British India: The Mahanirvana-Tantra

by J. Duncan M. Derrett

D C L. (Oxon.), LL.D., Ph.D. (Lond.). of Gray’s Inn, Barrister; Professor of Oriental Laws in the University of London

Essays in Classical and Modern Hindu Law

Volume 2: Consequences of the Intellectual Exchange With the Foreign Powers

1977

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A Juridical Fabrication of Early British India: The Mahanirvana-Tantra

This is a story of a well-intentioned fraud which may interest students of the interaction of cultures. The Mahanirvana-tantra (referred to below as MNT) is very well known as a religious treatise, especially revered in Bengal. It is described as “one of the original and most revered tantras"1), and readers will be astonished to learn that, if it is a fabrication of any kind, it is a juridical fabrication. Naturally it is much more than this. It is a work on a vast scale in which an old religious tendency is refurbished and re-presented comprehensively, with reformist motives. The large number of editions, both in the original Sanskrit and in Bengali and English translations, which has appeared is an additional proof of its popularity. It would be impossible to contend that the purchasers of these books had any interest in the legal as opposed to the religious elements. But the whole is made up of its parts, and it would be incorrect to appraise the MNT without scrutinising its highly deceptive legal portions.

In an important article Lallanji Gopal [The Śukraniti: a Nineteenth-Century Text, by Lallanji Gopal] showed that there was every likelihood that the Sukraniti, which was until then supposed to be an ancient Hindu treatise on statecraft, was in fact a fabrication of the first half of the nineteenth century2). It is unlikely, if not impossible, that his contention will be refuted: the only important refinement we can look for is a more precise location of the work in place and time. In an earlier article3) [Sanskrit Legal Treatises Compiled at the Instance of the British, by J. Duncan M. Derrett, 1961] the present writer discussed a number of works which were certainly, and others which were possibly, written in response to British suggestion or request. The light which this throws upon the cultural interactions of the two civilisations is somewhat novel. The picture could not be completed without a discussion of the MNT, and the writer regrets that he did not suspect its correct historical location at that time. To his chagrin he finds that he discussed the MNT in connection with the topic of pre-emption, realising that the work stood apart from the dharmasastra tradition represented in earlier treatises of an orthodox description, but failing to grasp why this was so4).

This discussion must go further than the previous article in two respects. The MNT [Mahanirvana-Tantra] belongs to the border-land between the pre-British and the settled British system of judicial administration, and therefore throws a lot of light on the hopes and fears of the native population at that time and the capacity of the indigenous civilisation to react to them. In a further respect the MNT exemplifies a traditional quality of the Hindu mind, which must be probed. A psychological point of general interest arises. Credulity and make-believe have a special place in Indian intellectual, or para-intellectual life. It is by no means certain that an alteration in the content of fairy-tales told to Hindu children will remove the tendency towards these manifestations for the future. However that may be, it will be found that we cannot discuss our present ‘fabrication’ without approaching this Indian phenomenon more than once. History often repeats itself, and a similar folly in the recent past may throw light on a certain intellectual inadequacy in an unexpected quarter, a century before.

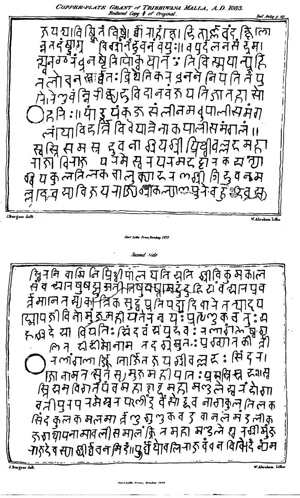

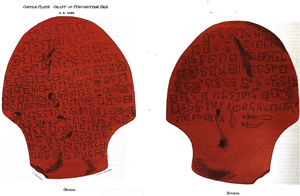

The Mahanirvana-tantra text

The work exists in very few manuscripts. Every one of them is on paper in modern Bengali script5). Manuscripts with the bare text of the verses are the majority (if the word majority has any meaning where the total is so small) and it is not clear whether the text with the commentary of Hariharananda Bharati (or Hariharananda Tirthasvami) is preserved in more than two manuscripts. This speaks at once for the work’s being modern, or rather, very modern. No trace of it is found in any work dealing with tantric religion prior to the eighteenth century6). Students of tantras either ignore this work7), or declare that its peculiarities do not quite fit it for the Bengali climate of thought8), in which it must obviously be placed historically and geographically.

It has been printed with and without commentary and in Bengali translation many times9): and several rumoured editions have not been traced. The popularity of the work is shared by its two English translations. That by Manmatha Nath Datta10) has been stigmatised as insufficient by the author (or supposed author)11) of the second, Arthur Avalon12). Avalon's edition of the text with the commentary has been printed at least twice, and his translation has gone into so many editions that Ganesh & Co. (Madras) who publish Avalon's many works on tantrism, evidently have a stable market. The popularity may in some measure be accounted for by the subtle appeal that the work has to the twin strands of modern Hindu thought, the mystic and antiquarian on the one hand and the yearning for cosmopolitan values on the other.

The tantra is regarded as a religious work, and purports to have been composed by the god Siva. It is in terms addressed to the goddess Parvati. There is no trace of the author’s identity (naturally), for that would have interfered with the illusion: so that the work is anonymous. At one time it was believed13) that the MNT was written by Raja Rammohun Roy or by Hariharananda Bharati himself. The first is highly improbable, as we shall see, and the second is unlikely, since in one place at least he seems not to have understood his text14). But, as we shall also see, it is very probable that the author’s work’s emergence was owed to Hariharananda.

Our special task is to examine the tantra with especial reference to the legal portions, for without these we cannot determine the mental climate in which the author wrote, and so we cannot establish its approximate date or conjecture how it came to be written. Having drawn conclusions from this material we can determine inferentially the relations towards this book on the part of Hariharananda, of Rammohun Roy, of the Brahma Samaj (which accorded the MNT considerable importance), and lastly of Arthur Avalon. This also is necessary, as it is not sufficient to establish how and where and when the book came to be written, but we must understand how it came to light, why it came into the prominence it did, and why, in the legal sphere, it did not come into greater prominence.

The Mahanirvana-tantra and Caste

It is generally known that Hinduism traditionally concerned itself with varna and asrama, that is to say with the hierarchical classification (or, commonly, ‘caste’) in which the individual was born, and the 'stage of life’ which he occupied at different periods of his life. In regard to both he was taught traditionally the merit or otherwise of observances, occupations, actions and abstentions, both those of a strictly religious nature and those with an ethical or moral significance. Contact with persons of other castes, the relationships which are allowed with them, the relations between the castes themselves in religious and purely secular contexts: all these were within the purview of the dharma-sastra (hereinafter called the Sastra), the traditional Hindu ‘science of righteousness'. This last is evidenced in an abundance of native literature, not to speak of discussions by non-Indians. It is generally possible to tell what the Sastra teaches on almost every problem that can arise in life.

The widest variety of opinions and psychological needs, felt over two millennia at the least, has provided in the sastra itself at various levels so wide a latitude for personal behaviour, always within the framework of caste, that until European influence began to be felt widely the weight of sastric sanction was not felt to be more of a hindrance than a privilege. The rise of European power produced reactions. It is a fact that Indians have a special, and perhaps unique faculty for adjusting themselves to foreign ways without themselves ceasing to be characteristically Indian. Acculturations are known the world over, but the ease with which Indians — for all their distinctive and pervasive civilization — from at least as early as the time of Alexander the Great, picked up foreign languages and became masters of foreign ideas about which they were curious, whilst still remaining nothing other than Indians, is not rivalled anywhere. The choice between assimilation or fossilization (as elsewhere) has not apparently presented itself. The characteristic Indian response to a new idea is not that it is wrong, but that Indian teachers must have said the same, or virtually the same, already. Outrageously novel notions are received in this constructively tolerant spirit, provided they arrive from a prestige-bearing quarter. The assumption is that Hindu learning and experience is exhaustive, and a new idea is merely one which was fallen temporarily out of view. It will then be re-expressed in Indian terms, perhaps distorted in the process, but none the less effectively absorbed. The acceptance of the Common Law with so many of its technicalities into India is only a single, though a very striking, example of this process. One might have expected that in order to be an expert practitioner in this very foreign and esoteric science one must forsake and repudiate traditional Hindu learning: but on the contrary many of the most successful practitioners at the Indian Bars have been brought up in the traditional way and have been great Sanskrit scholars in their own right. The late K. V. Venkatasubramania Iyer was not only the best Hindu law scholar of his day but taught the Madras High Court constitutional law, the newest and most foreign of legal manifestations India has known. And he was merely on outstanding recent example of an intellectual type. These general reflections have an intimate bearing on the MNT, which, whilst being extremely popular and highly revered, contains ideas unique in Hinduism.

Caste seems to be the pivot of this paradox. Hindus have long been aware of the absence of varna [social classes] outside India, and must have sought to justify caste to themselves. Many of the elaborate native expositions of the varna-theory may well owe their existence to this self-consciousness. When first Muslims and then Europeans ruled Bengal and gave promotion and lucrative appointments to Hindus of whom they approved, it could not be for long doubtful whether Hindu social and political theory would come under critical examination from Hindus aiming at desirable employment. Both Islam and Christianity being proselytising religions, many Hindus were brought to face the alleged merits of monotheism and a caste-less (or apparently caste-less) society: even if they had not been invited to do so by missionaries, their natural curiosity would have inspired them to investigate the reasons, if any, for the non-Hindu dharmas. The natural reaction would be to make a choice; either a non-Hindu dharma must be rejected because the alleged justification did not in fact support the practice, or because it could not be accommodated with prevailing Hindu concepts which already occupied the field; or, on the other hand, the justification being non-repugnant to Hinduism, the foreign dharma could be added to the spectrum of Hindu behaviours. A great help in this process was the natural, innate, ambivalence towards caste, especially in some areas of India where caste seems never to have had a firm hold, where Buddhism lingered long, and where in some senses and for some purposes people were anxious to pretend that it did not exist. An exaggerated respect for Brahmins (sometimes addressed as devata, ‘deity’, not always in fun?), and a desire to creep out from under the caste system, might well reside in the same head. Likewise tantric religion, which consists fundamentally of magical practices undertaken under the impression that worship of, for example, the goddess Kali, in esoteric ways would bring supernatural benefits to the worshipper, sought to supply to Brahmins and non-Brahmins alike a religious experience in which horror and awe might be combined, and in which the appetite for the marvellous and the secret, hitherto confined to Brahmins trained in the laborious methods known only to the orthodox, could be spread amongst persons whose only link was a common ritual. A boost was given to tantric performances and literature by the dominance of the Muslims, who possessed common rituals as, apart from tantrism, Hinduism did not; and the coming of Christianity to Bengal will have had an even greater effect. The common rituals of the sects of Christianity were much more elaborate and had, especially in the case of Roman Catholics, a strongly mystical and awesome element.

On this we may dwell for a moment. The drinking of spirits and wines was until the arrival of Europeans the privilege of the very lowest classes of Hindus, with the special exception of the numerically insignificant princely caste. In Bengal the unorthodox ways of the Punjab and Sind will have had no effect. The Brahmin ethic which still remained the dominant ethic of Bengali Hindu society, eschewed liquor. Islam purported to reject wine. Christians believed that drinking wine and eating flesh in the shape of bread, properly consecrated, was a great communion with the Divine. Persons of all sorts, once admitted to the church, could and should partake of this communion. From a Hindu point of view the horrid aspects of this act might be its chief virtues, provided one saw them in a tantric light. The things hated by orthodox Hinduism turned up in 'left-handed' worship by sects meeting in secret: eating meat, drinking liquor, committing incest. Tantrism had made these psychological aberrations almost respectable14a).

To the three otherwise reprobated acts commencing with the syllable ma known to older tantrism the MNT added two more, and we have the panca-makara, the five (otherwise questionable) entities commencing with ma, in which the tantric adept was entitled and expected to indulge during the ritual15). Some of the curiosities of the MNT are most easily explained if one assumes an attempt by the author to admit into relatively old tantric usages, such as are found in the Kularnava-tantra, notions derived from a comparative study of Christian, especially Roman Catholic, doctrine. The priest, the consecration of elements, the partaking of elements after initiation16), and in particular the notion of a wedding which is a religious communion as well as or indeed rather than a carnal copulation17), all appear in this tantra. The effect is, like so much Hindu teaching of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, not excluding the Hindu contribution (at times heavy) to the Theosophical Society's work, to draw what appears to be the foundation out from under the feet of the rival religion, leaving it with no exclusive merits which might claim converts from Hinduism. The present writer is impressed by the indebtedness of the MNT to Catholic Christianity, especially when we read that a kula-sannyasi or avadhuta (the kaula or tantric priest: avadhuta means literally ‘one who has shaken off, repudiated’, ‘a philosopher') can make Yavanas (i.e. even Muslims) pure (XIV. 177): in other words the merits of what corresponds to baptism belong to tantric Hinduism in no less an amplitude than to Christianity — for if a Muslim can be initiated a fortiori a Christian can be; that a kaula teacher must initiate a Candala (out-caste) or a Yavana who approaches him with a prayer for admission to the sect (XIV. 187); and that men of all the different dharmas in the world (thus explicitly including Christians) can be kaulas (ibid., 189); and when we note the mystic communion which all these people of different races and castes can enjoy together in common eating (III. 76—82) — a thing otherwise abhorrent to orthodox Hinduism. The great merits of Islam and Christianity, viz the absence of caste and the presence of communion, are no longer their peculiar gifts: Hinduism possesses them in full measure within the rather doubtful sphere of tantrism.

Nor is the matter left there. Caste and sect are often similar notions and sometimes popularly synonymous. The identity of the caste is often detected from the deity or deities worshipped in common. If one intends to abolish caste, whether out of desire to imitate or excel non-Hindus or from political motives, one automatically emphasises a monotheistic approach: the deities are in reality all one. The MNT does exactly this. The worship to be undertaken by the kaula, the member of this sect which is to be open to people of all religions, is that of Brahma, a deity who seldom plays in traditional Hinduism the role of a devata for the purposes of puja. It is quite justifiable to assert that the tantra is devoted to the worship of the Supreme Being and that the polytheistic traces, which remain numerous throughout the work, as well as the heaps of ‘mumbo-jumbo' which one expects to find in any tantric work, are superfluities which can be ignored if one wishes. The work is evidence that one very learned Sanskrit scholar believed that monotheism and a casteless society belonged to Hinduism and that the god Siva could be believed to have taught the details to the goddess Parvati17a). These details imitate the range of the dharma-sastra, with initiation, worship, class occupations, and installation of deities, the special rituals of the kaulas' chakra (or congregation under the direction of the avadhuta), and, last but not least, law.

The legal element in the tantra is very curious. First of all it is ample and more extensive in scope than genuine sastric works allow; next it is spread throughout the work in a manner hostile to any suggestion that the legal provisions are interpolations18. Further, the author expected the religious sanction attributed to the work as a whole to operate in a sastric fashion upon the conscience of the king. The occupations of the varnas are by no means missing from this treatise, because the social value of caste is not forfeited while the religious merit of castelessness is being introduced. As a result the king is expected to do his duty of protecting the people exactly as under the orthodox scheme. The author thus depicts the god Siva instructing kings to administer law according to his directions: and it is the religious sanction which is operative. The ‘king' whom the author has in mind cannot for long remain in doubt [King William the Third?]. The author must have been a Bengali — there is no evidence suggesting that he was a non-Bengali: the work did not exist while Hindus exercised royal powers over more than relatively small fragments of Bengal. The author must have wanted, therefore, to provide guidance for Muslim or European administrators. Which? This we must try to establish.

The Mahanirvana-tantra’s legal provisions

The legal portions of the tantra can be classified into three categories: (1) those more or less compatible with the sastra, though couched in language which an adept in the sastra might not have chosen (these it is neither convenient nor necessary to discuss); (2) those that are foreign to the sastra; finally (3) those which are not merely foreign but also evidently compatible with English law or legal ideas, whether in tone, origin, or even language.

It will be convenient to deal first with those which are foreign to the Sastra. This is easily detected, since the rules of the sastra may be found out in MM. Dr. P. V. Kane’s History of DharmaSastra, which, though in English, is copiously supplied with references to the original Sanskrit. Another useful work is MM. Dr. Sir Ganganatha Jha’s Hindu Law in its Sources. Foreignness to the sastra may take various forms. First, the rule as expressed may have no counterpart in any sastric text; next, though some counterpart may be found, the approach and language reveal an independent outlook, a different origin for the idea expressed. The last, and perhaps most important distinction is where the rule appears to be sastric in style and approach, but has a significant variation, as if to operate as an amendment of the sastra. It will not be convenient to subdivide the material exactly in accordance with these differences, partly because the categories overlap, and partly because those who wish to compare the original sources would find it advantageous to check the miscellaneous examples in the order in which they occur in the work.

A. Rules foreign to the sastra

The two great spheres of differences between the MNT and the sastra are marriage and inheritance. It will be noticed at once that these are the two main spheres of Anglo-Hindu law as first defined by the celebrated regulation of 1772 19). That regulation indicated that the law of the sastra should be applied to Hindus, but it did not indicate precisely what texts were to be consulted — nor indeed could such a provision have been made with any hope of success, even if many of the East India Company's officials time had comprehended what was meant. The MNT’s attention to these two topics could be read as an attempt to make up for the diffuseness and lack of clarity in the genuine sastric material.

IV. SOURCES OF LAW

In 1772 Hastings (acting on a proposition put up by the Committee of Circuit at Cossimbazar, 15 Aug. 1772)46 secured that indigenous systems should be applied, and that the judges of law should be specialists in those systems. The responsibility for the judgment should be shared between the official and the native jurist, both signing the final document. At this stage the first misconception obtrudes itself. The relationship between custom and the dharmasastra was taken for granted. Instead of using the native referees as sources of customary law, as Hastings might have done, and in a special case was later done,47 he directed that reference should be made only as to what the dharmasastra provided. The words of the provision, which later acquired the force of legislation, are not obscure: "In all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste and other religious usages or institutions, the laws of the Koran with respect to Mohamedans and those of the Shaster with respect to the Gentoos shall invariably be adhered to." The passage became law in the strict sense as s. 27 of the Regulation of 11 April 1780 and the word "succession" appeared in 1781, when, acting upon the advice of Sir Elija Impey, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, the Governor-General in Council enacted the Administration of Justice Regulation, of which it is s. 93.48 Impey's scheme introduced a further element which must have been suggested by the scope of the original "plan". Following the practice of early Charters of the East India Company, and acknowledging the need to supply a fundamental law which would guide judges where regulations and personal laws failed, secs. 60 and 93 of the Regulation of 5th July 1781 referred the judges to Justice, Equity and Good Conscience, about which more will be said below.49

It is evident, however, that Hastings' original selection of topics, not materially affected by Impey's supplementation, cannot possibly have been intended to exclude from the Company's courts the two indigenous systems of law so far as they concerned evidence, for example, or commercial topics, contract in general, or civil wrongs. The evidence against this from the views and activities of students of Hindu law of the period circa 1795-1830 is overwhelming. Taking a pragmatic view of the matter lawyers in the last century have inclined to suppose that that was in fact the intention as well as the effect of the legislation.50 It has even been assumed that India possessed no law on these topics -- strange ignorance has perpetuated baffling misconceptions. What Hastings really intended appears to have been this: -- in the listed matters51 the dharma-sastra must be the standard, and the sastris, or as they were honorifically called, "Pandits", must be consulted. In those spheres, he had been told (it seems), "unseen" considerations were paramount and the sastra was a universal criterion. In the non-listed matters the sastra need not be consulted, and the award of an arbitrator or the customary rule might be enforced without explicit reliance upon the classical jurisprudence. Proof of custom, where not agreed between the parties, would be taken according to the prevailing law of evidence, which must have been the Hindu law, for the judges knew nothing of the English law on the subject. This is the basis for Impey's larger addition: the practice, as English judges became more confident, was for them to assess the equitableness of the rules applied outside the listed subjects, and where they were satisfied that the customary rule was inappropriate or insufficient, the matter was not referred to the sastri (who was relieved of responsibility in such cases), but dealt with out of hand.52

When the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court came to be reviewed, regard was had to the actual practice of Hindus resident within the territory in question. Concerned not so much with the source of the laws to be administered as with the topics upon which it would be administered, the Regulating Act of 1781 provided that "inheritance and succession to land rent and goods and all matters of contract and dealing between party and party" should be determined in the case of Hindus by their own laws and where only one party was a Hindu "by the laws and usages of the defendant".53 Marriage, caste and other religious institutions had not in fact been commonly dealt with in the Supreme Court, but contract, inheritance, especially testamentary succession, had been normally within the business of the Mayor's Court and later the Supreme Court,54 and succession to land was thought to be exclusively within the competence of the local court.

Both in the mufassil courts, and their chief appellate court, the Sadr Diwani 'Adalat at Calcutta, and in the Supreme Court the Hindu law occupied a large place. The law was to be found out from the Pandits, and not by reference, for example, to a jury or any equivalent.

Meanwhile the ruler's responsibilities with regard to caste matters were by no means abandoned. The Company retained the right to superintend the administration of temples,55 and the management of places of pilgrimage.55 But in course of time a definite disinclination to interfere in matters of Hindu religion emerged, and even a distaste for cases involving claims to dignities and honours of a religious character and claims relating to ceremonies in idol worship "for the benefit merely of the few who profit by them".57 There was a definite withdrawal from responsibility. Castes were left to manage their own affairs; their decisions were, if otherwise unobjectionable, treated as valid, but they were not supported by state power. The rulers dissociated themselves from any mechanism tending either to maintain or to modify the existing caste structure.58 Jurisdiction to supervise castes was very early forbidden in Bombay Presidency; elsewhere the "law" laid down in caste tribunals was never enquired into unless some civil and proprietary right was alleged to have been violated. Any caste decision which was within the caste rules and arrived at without violating any rule of natural justice was immune from review.59 Belief that the caste was some sort of private association within the state upon an analogy with an English club was responsible for this considerable deviation from the pre-British position.60

-- The Administration of Hindu Law by the British, by J. Duncan M. Derrett, University of London; former Tagore Professor of Law, University of Calcutta

We may commence with VIII. 150-1 (numbered 151-2 in the translation of A. Avalon.

sarve varnah sva-sva-varnair brahmodvaham tatha 'sanam

kurviran bhairavi-cakrat tattva-cakrad rte sive.

ubhayatra mahesani saivodvaha prakirttitah

tatha 'dane ca pane ca varna-bhedo na vidyate.

This Avalon translates as follows: “Except when in the Bhairavichakra or Tattva-chakra 19a), persons of all castes should marry in their caste according to the Brahma form, and should eat with their own caste people. O Great Queen!, in these two circles, however, marriage in the Shaiva form is ordained, and as regards eating and drinking no caste distinction exists.” It is important to recognise at the outset that the MNT, admitting that sexual intercourse is a feature of tantric ritual, speaks of udvaha, “marriage”, and gives us to understand that a woman (presumably an unmarried woman or a widow) with whom intercourse is had, subsequent to the ceremony to be described, is wife to the man who enjoys her, whether or not he already has or had a caste wife. The Saiva marriage, which was an abortive attempt to reform the Hindu law of marriage from within, in partial imitation of Muslim and Christian freedom to contract marriages outside the religion, is thus seen as a development of the existing tantric ritual or orgy in which intercourse without any question of marriage played some role. The next relevant text is too long to set out here at length, seeing that it occupies IX. 267 to 284 in Avalon’s text, that is to say IX. 266-283 of Jivananda’s text. Avalon’s translation is to be found at his pp. 302-304. The verses follow a description of a Brahma marriage which has an orthodox or sastric air about it, and form the climax of book IX. But they are in some kind of contrast to the Brahma marriage, and since the rules follow the former and are at the climax the reader is left with the impression that this innovation (totally unknown to the sastra) is more important to the author than the material which introduces it. The content of the passage may be summarised thus: having said that another Brahma marriage should not be undertaken without the permission of the first Brahma wife (266), the author adds rather abruptly, “if the children of the Brahma wife or any of her family (vamsa) be living the children of the Saiva wife shall not inherit” (267). They are however entitled to food and clothing and the heir is bound to maintain the Saiva wife. There are two Saiva marriages: one is terminated with the chakra (the relationship ends — one hopes — when the congregation disperses), while the other is lifelong (this was the principal innovation, evidently) (269). The marriage is arrived at by mutual consent (parasparecchaya) and is performed by the male (called here viva). But he must first obtain the consent of the assembled congregation (anumanyatam) (271). He then asks the woman to accept him as husband (pati-bhavena vrnu) (273). The presiding priest utters a mantra invoking the protection of the tantric deities (276) and the congregation say Amen (svasti). The priest sprinkles the couple with wine or sacred water. They bow to him and then “carefully carry out whatever they have promised” (278). The author says that in Saiva marriage there are no restrictions of caste or age, but the woman must have no husband and not be within the prohibited degrees (this is evidently intended to lay a foundation for a respectable marriage) (279). But if this Saiva wife has a menstrual period thereafter, the husband, if he desired a son, may abandon her (tyajet). The offspring of a Saiva marriage is of the same caste as the mother should she be of the lower caste, but if the order of castes is reversed he has the status of samanya ('equal', 'commoner '). Such sons would have no status in the funeral rites under the sastra; but since the kaulas, or tantric adepts, have allowed the marriage, naturally from their point of view the issue are legitimate: therefore at a time when a legitimate son would according to the sastra perform orthodox rituals, the Saiva son must feast the kaulas only (and not Brahmins, qua Brahmins) (282).

The general tone of the MNT on sexual matters is puritanical. The author evidently hopes to elevate his Saiva marriage into a respectable institution, a means of liberalising Hindu society, providing tantrism itself becomes more respectable as well as more widely patronised, and this latter could certainly be hastened if tantrism were to be cleansed of merely libidinous elements. It is important to note that at 283-4 the author attaches religious sanction both to the desire for intercourse and to the saiva-dharma, an expression which means both the laws promulgated (here) by the god Siva, and the system of Saiva (i.e. Siva’s) marriage just set out. The tendency is confirmed by a verse in the section dealing with sexual misbehaviour (XI. 46):

parinitas tu ya naryo brahmair va saiva-vartmabhih

ta eva dara vijneya anyyah sarvah para-striyah.

Avalon translates (p. 346): "A man should consider as wife only that woman who has been married to him according to the Brahma or Shaiva form. All other women are the wives of others.” It is a sin to look lustfully on the wife of another (47).

A further statement that the children of a Saiva marriage are not to inherit in the presence of either issue of a Brahma marriage or close relatives (sapindas) of the deceased’s father or mother is followed by the rule that the Saiva wife and children are entitled to maintenance. To confirm the married status of this woman he continues with a rule (XII. 60) that she cannot look to her father or other relations for her maintenance: her Saiva husband must support her, provided she behaves herself. “Therefore, the father who marries his well-born daughter according to Shaiva rites by reason of anger or covetousness will be despised of men (61)” (Avalon p, 368). But the issue of the Saiva marriage inherit before all remote relations and strangers (62). Thus the novel institution is settled into the law not merely of marriage but, quite practically, those of maintenance and inheritance as well. The warning not to give away a daughter in the Saiva form without due reason (for the Brahma form will entitle the girl to ornaments and other prestige-bearing expenditure, whereas the Saiva form avoids all the conspicuous consumption dear to the Hindu) is supported by a further rule (at XII. 125) that an only daughter should not be given away in this form, and it is possible to read the verse in such a way as to include a prohibition of a man who has one wife giving away that wife in a Saiva marriage ceremony (Avalon, p. 376).

The inheritance provisions of the MNT have two characteristics that mark them out from all sastric works. First the detail is very elaborate. It is far more explicit than would be required in a native law book. The explicit provisions of the Vivadarnava-setu [Anglo-Hindu law] (1773 to 1775) are a rough parallel, and this is very significant20). Secondly, the language is markedly un-sastric. Words occur which are unknown to the sastra, and which are evidently translations into Sanskrit of technical English expressions. The passages in question are XII. 19, 21, 25, 26-28, 30-40, 42-63. A summary will serve our purpose. A son's son is entitled to the property rather than a wife or a father (this would be correct in Sastric law) ‘by reason of his being a descendant’ (adhastaj janma-gauravat, literally, because of the importance of downward, or lower, birth). This extraordinary expression (Avalon, p. 364) betrays not so much the hand of the novice as that of one who intends to communicate Hindu ideas in a foreign diction (though the medium is Sanskrit). Avalon’s note to this verse (XII. 19) shows no sign of his having grasped how strange the expression is in view of the fact that Hindu law is well equipped with discussions of inheritance and never contemplates this way of putting it. He says “property primarily descends", unaware that the metaphor of descent, so well embedded in English legal language, is by no means universal. There is a privilege for males (21) and that is why a grandson will exclude daughters, though they are very near. There is a definition of stridhanam (woman’s peculiar property)21), and we are told that all of this passes to the svami (svami need not mean husband here) and “then” (presumably in his absence) the nearest will take her estate adha urdhva-kramad, “according to the order of down and up”, or rather, “by reason of the going down or up”, i.e., literally, “according to descent and ascent”(!). This is a very comical attempt to translate an English portmanteau phrase. If an English student of Sanskrit had been trying to turn an English legal idea into that language he might have produced a similar result. The inheritance of the widow depends on her good behaviour (27) in the care of her husband’s family. Even suspicion of misbehaviour will prevent her inheriting (28): this is emphatically contrary to Sastric law and naturally to Anglo-Hindu jurisprudence22). There is a very extraordinary expression at verse 30. It is an endeavour to explain what in subsequent periods of Anglo-Hindu law was worked out in detail, but was naturally obscure on the footing of the texts of the Bengal school (usually called the Dayabhaga school) of Hindu law Avalon translates (p. 365): ‘'If the woman who inherits her husband’s property dies leaving daughters, then the property is taken to have gone back to the husband and from him to the daughter.” Correctly he should have written “a daughter” for “daughters”, but the slip is trivial. The property goes to the daughter, says the text literally, punah svami-padam gatva, i.e. “having reverted to the husband (owner)”. Is it assumed that the husband is already dead, but the property was originally his? If the widow took it subject to what is now called the “limited estate”23), one of the incidents thereof was that on the widow’s death (or surrender) the next heir of the last male holder (svami) took it as if he had died when the widow died. Verse 31 explains further: “So, property which has gone to the widow of a son during the lifetime of a maiden (daughter), on her (the widow’s) death it must revert to the ‘owner’ (here svami means the last male holder’s father) and from (her) father-in-law it will go to his daughter.” This is incorrect Dayabhaga law put in very unconventional language. Nowadays we should express the thing by saying that if P died leaving a son S and a son’s wife SW and a daughter D, and then S died leaving SW and D, and then SW died, the estate which had formerly belonged to P would not pass to the personal heirs of SW but would pass to the nearest heir of S as if S had died when SW died and the nearest heir of S must be sought through P, his father: but we should not choose D as the reversionary heir, because D is not the nearest heir of S, as the sister is never an heir at Dayabhaga law24). Thus the author of the MNT, seeking to combine the native notion of the limited estate with a foreign notion of nearness of blood and the search for the descendant of the previous owner (see below), puts what is in fact an innovation into language at least comprehensible to a foreigner. In verse 32 we read “Likewise, property which has passed to a mother in the lifetime of the father’s father (namely the mother’s father-in-law) must, on her death, go to her father-in-law by reason of her son, by reason of her husband. In other words the last male holder's (her dead son’s) line’s nearest representative, namely her husband s father, must take the property. This would be correct at Dayabhaga law. The rules which follow bear out both points, namely the effect of the limited estate and the claim of the reversioner, and the concept of “descent”, etc. At v. 35 we are told “In the absence of descendants (adhastananam virahat), when the estate cannot descend (literally, go down’), then it must ascend (literally, go up’) only by means of him through whom a descendant was readied”. Avalon’s translation seems incorrect. The property, it seems, goes by the way it came, and the illustrations bear this out. Many intricate questions of inheritance are now handled, and there is a general conformity with the Dayabhaga law. The way in which the rules are set out has nothing in common with conventional Dayabhaga exposition25). But striking divergences from that law are found. Half-brothers and full brothers inherit together: v. 39.26) Daughter's sons cannot inherit in the lifetime of daughters (which is correct), but daughters inherit after sons (40-41). Stridhanam (cf. v. 25) inherited from others than the husband reverts to the source from whence it came (42): this seems new26a). There is an odd phrase at 43: preta-labdha-dhana, “property obtained from a dead man (i.e. deceased’)”. Verse 46 has much interest:

pitrvyat sannikarse ’tra tulyau bhratr-pitamahau

dhanam pitr-padam gatva prayatur bhrataram bhajet.

It is perfectly true that, as he says, “in point of propinquity both brother and father’s father are to be preferred to the fathers’s brother”. From the western standpoint the number of degrees is the same in the case of the brother and the grandfather, whereas in the case of the uncle three steps have to be taken. He continues, “the property, having reverted to the father should resort to the deceased’s brother”. The word for ‘deceased’ is a neologism [a newly coined word or expression], prayatr, a literal translation surely of ‘predecessor’, much better than the preta noticed above. This conception of property passing through relations (whether living or dead) fits English concepts of descent of real property27), but is quite foreign to Hindu law as generally understood.

More foreign still is verse 52, according to which the well-behaved son's daughter whose parents are dead and who has no brother may share her father’s father's property along with her father’s brothers, i.e. females have a right of representation. This is unknown to Hindu law, but follows the English, or at any rate a western, pattern28). To our author the son’s daughter seems a more worthy heir than even the deceased’s own daughter (v. 53): this is most irregular from a traditional Hindu standpoint. On the whole the scheme of inheritance is a peculiar one, being neither what the Dayabhaga law required nor what English law suggested, but a curious amalgam of the two expressed constantly in terms of ascent and descent, such as would occur only to one who had viewed Hindu customs through western eyes. To him two principles stand out throughout the scheme: that males should have priority over females, that property should descend rather than ascend, and that where descent is not possible the property ascends and descends through senior relations (cf. 57). This has an undeniable and peculiar affinity with the old English law of descent of real property, and seems comical in a Hindu setting.

Passing from the important topics of marriage and inheritance we may continue with rules foreign to the sastra. It may be convenient to proceed in the order of the book. At VIII. 125 we are given a rule about the distribution of prize amongst soldiers. Shares are to be given according to merit. Included in prize may be items conceded under the peace-treaty. This has no counterpart in the sastra29). At VIII. 141 we are told that the interest on barley, wheat or paddy is 25 per cent per annum, whereas in the case of metals the interest is 12-1/2 per cent. The last is novel. There is no means of knowing whether any actual usage in Bengal corresponded to it30). A rule rather like the allegation of 'superior orders’ appears at XL 80: “The man who kills another in obedience to an imperative order is not guilty of killing, for it is the master’s killing. This is the command of Siva.” This appears at Avalon’s translation, p. 350, but I have very slightly amended his version. There is nothing in the sastra to correspond to this, nor, it would seem, to XI. 91: After punishing them severely the king should banish (niryapayet, an unexpected word) from his country those mortals who give false evidence or who, as arbitrators, are partial (paksapatinah)". On the number of witnesses, a strange rule also appears, at v. 92: six, four or three are enough, but so is the evidence of two witnesses of well-known righteousness31). The means whereby evidence may be taken from blind and deaf-and-dumb witnesses, at v. 94, is supplementary to the sastra. The punishment of forgers (double that of false witnesses) is also new: v. 96 32). A completely un-sastric rule about eating appears at XI. 132: there is nothing wrong in eating on the bade of an elephant, on a large block of stone, on a very heavy piece of wood etc. A further foreign passage is that dealing with maintenance at XI. 58-63. Very comprehensive rules are given about guardianship of a child without parents or paternal grandfather. At 62-3 the rules about maintaining relatives are wrongly translated by both Avalon (p. 348) and Datta. The correct translation appears to be, “O Ambika! The king, considering the wealth of a man, should force him to give clothing and food to his father, mother, father’s father, father’s mother, likewise a woman (i.e. concubine), to an illegitimate son and to a sonless maternal grandfather and to a maternal grandmother, if they are poor.” The list is of great interest, as it differs from the sastric provisions33), but the expression for illegitimate son (ayo-gya-sunu) is highly curious: the notion “illegitimate” can be translated “what is not proper according to law”, and this might well be rendered ayogya. Needless to say, the concept “illegitimate” as such (in contrast to ‘bastard’)34) is unknown to the native Hindu law.

The list can be brought to a rapid close with a series of striking rules, all unknown to the sastra as they stand. XII. 83—5, 87 deals with the man who disappears, XII. 94 deals acutely with the administration of charities35), and XII. 97-101 has a treatment of the thorny problem of earnings, exempt from partition. The disqualifications from inheritance at XII. 102-4 go, in part, beyond what the sastra provides36). So does XII. 105-6 which deals with title to property which has been found. The king takes a tenth of unowned property and the finder takes nine tenths37). The curious word prapta, which would translate the English word ‘finder’, should be noticed in passing. There is a new rule on cultivation (XII. 113), on the building and use of tanks (115-117). XII. 118-123 contain miscellaneous rules. The pledge of an undivided interest is forbidden. When animals are pledged and the pledgee works them with the owner’s consent, the pledgee (dharta, literally ‘supporter’ or ‘undertaker’) must feed the animals. The present writer has a suspicion that dhartr is used in the sense of ‘person liable’. ‘Liable’ (verpflichtet), a term so well known in English law, is difficult to explain, let alone translate. The context is purely Hindu38), but the word is unexpected. XII. 121 is foreign in that it requires definiteness in all loans, whether in point of duration or rate of interest: a definiteness that must often have been wanting in such contracts between Hindus. Verse 123 is highly curious:

krama-vyatyaya-mulyena dravyanam vikraye sati

nrpas tad anyatha kartum ksamo bhavati Parvati.

“O Parvati! The king is entitled to set aside (render of no effect) a transaction when there has been a sale of objects, the price being contrary to (or in breach of) the order laid down.” This suggests (pace Avalon, whose guess is recorded in his footnote to p. 376) that a scale of prices must have been fixed for certain commodities, and krama must here mean ‘scale’. The notion of setting aside a sale, not the notion of fixed prices, is novel to Hindu law of the pre-British period. The curious phrase ksamo bhavati, ‘is able to’ is quaint in view of the normal sastric diction, which commands or authorises the king to do innumerable acts in the potential mood of the main verb. But if ksamo bhavati translates ‘has jurisdiction to’, it is quite comprehensible. Finally, at XII 126-7 we have some very general particulars about agents (who do not figure prominently in sastric law), including a Sanskrit word for “principal”, niyantr, which we have never seen before in this sense. It is in fact quite apt for the purpose.