Soma, food of the immortals according to the Bower Manuscript (Kashmir, 6th century A.D.)

by Marco Leonti, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Cagliari, Via Ospedale 72, 09124 Cagliari (CA), Italy

Laura Casu, Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Cagliari, Via Ospedale 72, 09124 Cagliari (CA), Italy

Journal of Ethnopharmacology

Available online 5 June 2014

© 2014 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Corresponding author. Tel.: þ39 0706758712; fax: þ39 0706758553.

E-mail addresses: [email protected], [email protected] (M. Leonti).

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

“By this time the soma had begun to work. Eyes shone, cheeks were flushed, the inner light of universal benevolence broke out on every face in happy, friendly smiles”

-- Brave New World, Aldous Huxley, 1932

Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance: Food is medicine and vice versa. In Hindu and Ayurvedic medicine, and among human cultures of the Indian subcontinent in general, the perception of the food-medicine continuum is especially well established. The preparation of the exhilarating, gold-coloured Soma, Amrita or Ambrosia, the elixir and food of the ‘immortals’ -- the Hindu pantheon -- by the ancient Indo-Aryans, is described in the Rigveda in poetic hymns. Different theories regarding the botanical identity of Soma circulate, but no pharmacologically and historically convincing theory exists to date. We intend to contribute to the botanical, chemical and pharmacological characterisation of Soma through an analysis of two historical Amrita recipes recorded in the Bower Manuscript. The recipes are referred therein as panaceas (clarified butter) and also as a medicine to treat nervous diseases (oil), while no exhilarating properties are mentioned. Notwithstanding this, we hypothesise, that these recipes are related to the ca. 1800 years older Rigvedic Soma. We suppose that the psychoactive Soma ingredient(s) are among the components, possibly in smaller proportions, of the Amrita recipes preserved in the Bower Manuscript.

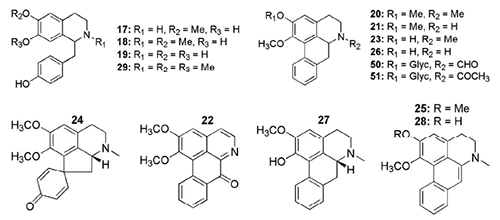

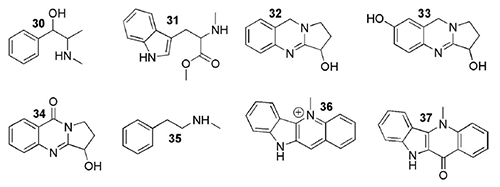

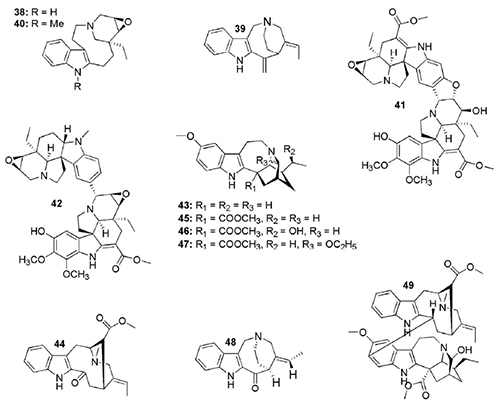

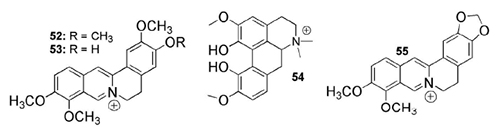

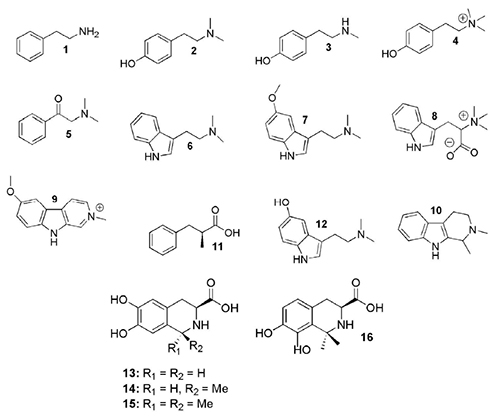

Materials and methods: The Bower Manuscript is amedical treatise recorded in the 6th century A.D. in Sanskrit on birch bark leaves, probably by Buddhist monks, and unearthed towards the end of the 19th century in Chinese Turkestan. We analysed two Amrita recipes from the Bower Manuscript, which was translated by Rudolf Hoernle into English during the early 20th century. A database search with the updated Latin binomials of the herbal ingredients was used to gather quantitative phytochemical and pharmacological information. Results: Together, both Amrita recipes contain around 100 herbal ingredients. Psychoactive alkaloid containing species still important in Ayurvedic, Chinese and Thai medicine and mentioned in the recipe for ‘Amrita-Prâsa clarified butter’ and ‘Amrita Oil’ are: Tinospora cordifolia (Amrita, Guduchi), three Sida spp., Mucuna pruriens, Nelumbo nucifera, Desmodium gangeticum, and Tabernaemontana divaricata. These species contain several notorious and potential psychoactive and psychedelic alkaloids, namely: tryptamines, 2-phenylethylamine, ephedrine, aporphines, ibogaine, and L-DOPA. Furthermore, protoberberine alkaloids, tetrahydro- - carbolines, and tetrahydroisoquinolines with monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAO-I) activity but also neurotoxic properties are reported.

Conclusions: We propose that Soma was a combination of a protoberberine alkaloids containing Tinospora cordifolia juice with MAO-I properties mixed together with a tryptamine rich Desmodium gangeticum extract or a blending of Tinospora cordifolia with an ephedrine and phenylethylamine-rich Sida spp. extract. Tinospora cordifolia combined with Desmodium gangeticum might provide a psychedelic experience with visual effects, while a combination of Tinospora cordifolia with Sida spp. might lead to more euphoric and amphetaminelike experiences.

1. Introduction

The attempt of botanically identifying Soma, or the ingredients of soma-rasa, the ritual and intoxicating drink of the ancient Indo-Aryans, produced a wealth of theories and literature (e.g. Wasson, 1968; Falk, 1989; Flattery and Schwartz, 1989; McKenna, 1992; McDonald, 2004). Praised in the Rigveda as ‘Soma’ and in the Avesta as ‘Haoma’, both terms have their origin in the Indo-Iranian ‘sau’ meaning to “crush or grind by pressing with a pestle in a mortar” (Flattery and Schwartz, 1989, p.: 117). The Rigveda is the oldest text transmitted from the Vedic period, which lasted from approximately 1900 B.C. to around 1200 B.C. (Witzel, 1997). In the Vedas, Soma was simultaneously conceived of as a god, a plant, and as the earthly equivalent to Amrita (‘non-death’–‘a-mrta’), the celestial food of the immortals (see McDonald (2004)). The central geographic area of the Rigveda is the Punjab (Eastern Pakistan and North-western India), which coincides with what is generally regarded as the homeland of the Indo-Aryans (Witzel, 1987; McDonald, 2004).

Most commentators who approached the botanical identification of ‘the’ soma plant were tempted by the scarce hints at plant morphology occurring in the 9th book (‘Mandala’, Sanskrit: ) of the Rigveda (see for example: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/ The_Rig_Veda/Mandala_9). The contradictory and multi-interpretable metaphors and botanical allusions throughout the 114 hymns dedicated to Soma in the 9th Mandala, however, render an unambiguous botanical identification very difficult. In fact, the different commentators do not even agree whether Soma was an herb, a creeper, a tree or even a fungus. Hymn 96, verse 2 alludes to a climber or vine: “Men decked with gold adorn his golden tendril…”. Hence, different commentators agreed that Soma was a vine or a climber. Srivastava (1954, p.: 26) writes that in the Rigveda soma “is described as a milky climbing plant, the juice of which was immensely liked by the celestial gods…” and that soma-rasa (the Soma juice) was prepared by pounding the entire creepers collected in the morning (p.: 28). Although Shrivastava gives no references he states that several authors suggested different botanical identification including Sarcostemma acidum (Roxb.) Voigt (Apocynaceae). Also Lewin (1973, p.: 216) mentions, amongst other species, two latex-bearing Apocynaceae as possible ingredients for Soma: Periploca aphylla Decne. (unresolved, Apocynaceae) and Sarcostemma brevistigma Wight & Arn. (= Sarcostemma acidum (Roxb.) Voigt, Apocynaceae). Milk plays indeed an important role in the preparation of Soma but there are no clues that the soma plant itself had a milky juice or latex. Rather it appears that a golden or yellow (also red-brownish) watery plant juice produced with the help of pressing stones, was either first blended with milk and then cleansed by means of a fleece or sheep's wool or that the juice was first cleansed and then blended with milk and subsequently mixed with a sort of oil:

Rigveda, Mandala 9, hymn 101, verse 11: “Effused by means of pressing-stones…” h. 101, v. 12: “These Soma juices, skilled in song, purified, blent with milk and curd, when moving and when firmly laid in oil, resemble lovely suns”. H. 69, v. 9: “…effused, they pass the cleansing fleece, while, gold-hued, they cast their covering off to pour the rain down.” H. 72, v. 1: “They cleanse the gold-hued: like a red steed is he yoked, and Soma in the jar is mingled with the milk.” H. 103, v. 2: “Blended with milk and curds he flows on through the long wool of the sheep.” H. 107, v. 26: “Urged onward by the pressers, clad in watery robes, Indu is speeding to the vat.” H. 8, v. 6: “When purified within the jars, Soma, bright red and golden-hued, hath clothed him with a robe of milk.” H. 109, v. 21: “…they cleanse thee for the gods, gold-coloured, wearing water as thy robe.” H. 107, v. 10: “Effused by stones, o Soma, and urged through the long wool of the sheep, thou, entering the saucers as a man the fort, gold-hued hast settled in the wood.” H. 31, v. 5: “For thee, brown-hued! the kine have poured imperishable oil and milk.” H. 98, v. 7: “Him with the fleece they purify, brown, golden-hued, beloved of all, who with exhilarating juice goes forth to all the deities”. H. 78, v. 4: “He whom the gods have made a gladdening draught to drink, the drop most sweet to taste, weal-bringing, red of hue.” H. 107, v. 4: Cleansing thee, Soma, in thy stream, thou flowest in a watery robe: Giver of wealth, thou sittest in the place of law, o god, a fountain made of gold.” (See: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Rig_Veda/Mandala_9).

Flattery and Schwartz report that Sarcostemma acidum is one of the plants used today by Brahmans as a substitute for the ancient Soma and also Padhy and Dash (2004) have gathered anecdotal evidence that in some parts of India a sort of soma ritual is still being practiced employing Sarcostemma acidum, which, however, does not have the capacity to alter one's state of mind. This results in the paradoxical situation that, while in present day soma rituals the recited liturgies allude to the intoxicating effects of the potion, the plants used in contemporary settings lack any intoxicating properties (Flattery and Schwartz, 1989, p.: 4). In fact, the hymns in the 9th Mandala of the Rigveda speak of “granter of bliss” (h. 1, v. 3), “runs forth to the luminous realm of heaven” (h. 37, v. 3), “rapturous joy” (h. 45, v. 3), “bring us all felicities” (h. 62, v. 1), “bringing wisdom and delight” (h. 63, v. 24), “light that flashes brilliantly” (h. 64, v. 28) “gladdening draught to drink” (h. 78, v. 4), or “exhilarating juice” (h. 98, v. 7). Flattery and Schwartz (1989) defend the opinion that the botanical identity of ‘Haoma’ in the Iranian traditions as well as that of ‘Soma’ of the Hindu traditions is the Syrian rue (Peganum harmala L., Nitrariaceae) containing harmala alkaloids with monoamine oxidase inhibitory (MAO-I) activity. Falk (1989) on the other hand argues that “there is no need to look for a plant other than Ephedra for the original Soma” since ephedrine (30) containing Ephedra spp. are referred to as ‘hum’, ‘hom’, ‘som’ or ‘soma’ in different languages and because the Parsi in Iran still use Ephedra sp. in their Haoma ritual. Hints from the artistic and mythic wealth of India and southeast Asia led McDonald (2004) to hypothesise that the botanical identity of Soma is to be found in the ‘eastern’ or ‘sacred’ lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Nelumbonaceae). The sacred lotus is not only a highly symbolic plant associated with Hindu and Buddhist gods (McDonald, 2004) but also an important food and medicinal plant (Mukherjee et al., 2009).

We argue that focusing on the identification of a single “soma species” or single soma recipe contributed much to the inconsistencies present in the different identification attempts and the apparent contradictions between the proposed theories and botanical species. In this contribution we attempt to circumscribe the plant species that come into consideration for the preparation of Soma and try to identify Soma's botanical identity. Systematic and multidisciplinary botanical and medico-therapeutic analyses of ancient medical scripts and herbal books can help to provide more verified insights into the history and evolution of plant use (Leonti, 2011). We assume that over the course of time the Soma recipe evolved and that more than only one soma recipe existed and that Soma was a more or less complex herbal drug formulation including different species, some more symbolic, some less indispensable for the mind-altering effect, than others. Our attempt of botanically identifying soma is based on the analysis of two herbal formulations reported in the so-called “Bower Manuscript” referred therein as (I) “Amrita-Prâsa clarified butter” (Hoernle, 2011, p.: 90–91) and (II) “Amrita Oil” (Hoernle, 2011, p.: 106–107).

2. The Bower Manuscript

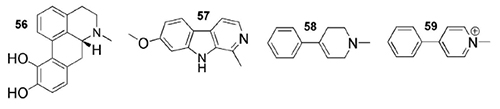

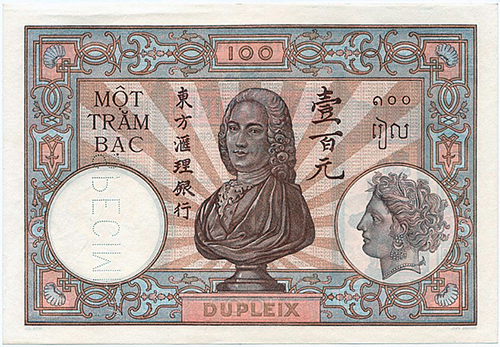

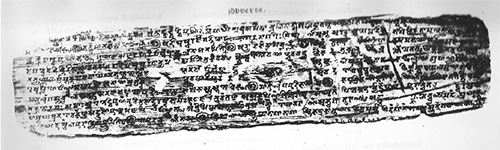

Fig. 1. Pôthi of the Bower Manuscript, taken from Hoernle (2011, Plate VII).

The Bower Manuscript (BM) was dug out from a man-made, mound-like construction called ‘stûpa’ close to the underground city of Ming-oï-Qumturâ, 16 miles west from Kuchar (Hoernle, 2011, p.: iv). Kuchar is an oasis settlement with a Buddhist history situated on the Silk Road in Eastern Turkestan (China) north of Takla Makan. The manuscript is named after Lieutenant Hamilton Bower, who acquired the script in Kuchar in 1890 (Hoernle, 2011). The BM is written in, as Rudolf Hoernle [1841–1918] calls it, ungrammatical Sanskrit, a mixture of literary and popular Sanskrit. The script used throughout the manuscript is known as the ‘Gupta’ script coinciding with the era of the Gupta Empire [300–550 A.D.] of northern India (p.: xxvi). Remarkably, the BM is the hitherto oldest known original medical treatise from the Indian subcontinent (Hoernle, 2011, foreword and p.: lxviii). Written by four different authors (p.: xxxvii) on birch bark leaves (cut from periderm of Betula utilis D. Don (Betulaceae)), the BM is actually a collection of seven separate manuscripts originally presented in the form of a ‘pôthi’ (Fig. 1; p.: xvii) a collection of loose leaves in-between two wooden boards held together “by a string which passes through a hole drilled through the whole pile” (p.: xvii). Pôthis seem to be South Indian in origin, since the palm-leaf of Corypha umbraculifera L. (Arecaceae) was the original writing support of pôthis and thereby also determined their overall shape (p.: xviii). Himalayan birch, (Betula utilis) is native only to Kashmir and Udyâna in the North of India (p.: xx). The writing style and the fact that the authors used birch bark for their records led Hoernle to conclude that the scribes of parts I–III and parts V–VII, most probably Buddhist monks, migrated from an unknown location in India via Kashmir or Urdyâna to Kuchar, where they finally manufactured the manuscripts.

Through a comparative analysis of particularities in the script-style of the BM, Sander (1987) argues that especially parts I–III contain elements typical for ancient Kashmiri scripts and that the BM is in reality a product of Kashmir itself. Sander (1987) provides also evidence suggesting that the BM was written between the beginning and the middle of the sixth century A.D. shifting the date of origin proposed by Hoernle around 150 years towards the present and towards the end of the Gupta Empire. According to Hoernle (p.: xxxvi), the author of part II, which contains the two recipes that are the object of this analysis, probably came from the northern fringe of the northern part of the Indian ‘Gupta script’ area (Hoernle, p.: xxxvi).

3. Methods

The plant species contained in both formulations, the “Amrita-Prâsa clarified butter” (I) and the “Amrita oil” (II), botanically identified by Hoernle (2011) through an analysis of their Sanskrit names and provided with Latin binomials were cross-checked with theplantlist.org (http://www.theplantlist.org/) for synonyms and their accepted contemporary Latin binomials. The updated Latin binomials appear framed in square brackets in recipes I (4.1.) and II (4.2.).

A literature search focusing on psychoactive secondary metabolites and associated pharmacologic effects was performed with the updated Latin binomials and the help of search engines such as Scopus and Pubmed. Special attention was given to quantitative phytochemical analyses.

4. Recipes

4.1. (I) The Amrita-Prâsa clarified butter (Hoernle, 2011, pp.: 90–91).

The numbers in brackets refer to the ślôka [sûtras], see also Srivastava (1954, p.: 153), while the superscript numbers are identical to Hoernle's text and refer to notes therein.

“The Amrita-Prâsa Clarified Butter,55 in 11 ślôka and 1 pâda. (Verses 108-119a.). I will now describe the ambrosia-like elixir, which increases the strength of men, the so-called Amrita-prâśa (or Food of the Immortals), a most noble kind of clarified butter. (109) Take one prastha each of the juice of emblic myrobalan [Phyllanthus emblica L., (Phyllanthaceae)], Kshîravidârî (Ipomoea digitata) [Ipomoea cheirophylla O'Donell, (Convolvulaceae)] and sugar cane [Saccharum officinarum L., (Poaceae)], and similarly of the milk of a heifer (110) one prastha, and add one well-measured prastha of fresh clarified butter. Throw in, also, pastes33made of one half pala each of the following drugs: (111) Rishabhaka56 [unknown and substituted], Riddhi56 [unknown and substituted], liquorice [Glycyrrhiza glabra L., (Fabaceae)], Vidârigandhâ (Desmodium gangeticum) [Desmodium gangeticum (L.) DC., (Fabaceae)], nPayasyâ (Gynandropsis pentaphylla) [Cleome gynandra L., (Cleomaceae)], Sahadêvâ (Sida rhomboidea) [Sida rhombifolia L., (Malvaceae)], Anantâ (Hemidesmus indicus) [Hemidesmus indicus (L.) R. Br. ex Schult., (Apocynaceae)], Madhûlikâ (Bassia latifolia) [Madhuca longifolia (J. König ex L.) J.F. Macbr., (Sapotaceae)] and Viśvadêvâ (Sida spinosa) [Sida spinosa L., (Malvaceae)], (112) both Mêdâ56 [unknown and substituted], Rishyaprôktâ (Sida cordifolia) [Sida cordifolia L., (Malvaceae)], Śatâvarî (Asparagus racemosus) [Asparagus racemosus Willd., (Asparagaceae)], Mudgaparnî (Phaseolus trilobus) [Vigna trilobata (L.) Verdc., (Fabaceae)] and Mâshaparnî (Teramnus labialis) [Teramnus labialis (L. f.) Spreng., (Fabaceae)], Śrâvanî (Sphaeranthus indicus) [Sphaeranthus indicus L., (Asteraceae)], cowhage [Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC., (Fabaceae)] and Vîrâ (Uraria lagopodioides) [Uraria lagopodoides (L.) DC., (Fabaceae)]. (113) Further add one kudava each of raisins [Vitis sp., (Vitaceae)], dates [Phoenix dactylifera L., (Arecaceae)], jujubes [Ziziphus jujuba Mill., (Rhamnaceae)], and half as much each of walnuts [Juglans regia L., (Juglandaceae)], Tinduka (Diospyors Embryopteris) [Diospyros atrata (Thwaites) Alston or Diospyros albiflora Alston, (Ebenaceae)] and Nikôchka (Alangium decapetalum) [Alangium salviifolium (L.f.) Wangerin, (Cornaceae)].

(114) Having boiled and strained the whole, let it stand in a clean vessel, and when it has cooled, add one prastha of well-clarified honey, (115) and sixteen pala of choice white sugar. Then take one half pala of black pepper [Piper nigrum L., (Piperaceae)] and one pala of small cardamoms [Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton, (Zingiberaceae)] (116) powder them finely, and, having sprinkled them over the whole, stir it with a ladle. Of this preparation a dose suited to the patient's power of digestion may be administered, (117) and when it is digested, rice-milk, together with the broth of the flesh of land-animals, may be given. This Amrita-prâśa is an excellent preparation for increasing the strength and colour of men; (118) it may be given in cases of weakness induced by consumption or ulcers, also to the old, the feeble and the young, also to those who are suffering from fainting, asthma, and hiccough. (119a) This preparation of clarified butter, being a composition of Âtrêya's, is famed under the name Amrita (or ‘ambrosia’).”

HASCHICH FUDGE

(which anyone could whip up on a rainy day)

This is the food of Paradise -- of Baudelaire's Artificial Paradises: it might provide an entertaining refreshment for a Ladies' Bridge Club or a chapter meeting of the DAR. In Morocco it is thought to be good for warding off the common cold in damp winter weather and is, indeed, more effective if taken with large quantities of hot mint tea. Euphoria and brilliant storms of laughter; ecstatic reveries and extensions of one's personality on several simultaneous planes are to be complacently expected. Almost anything Saint Theresa did, you can do better if you can bear to be ravished by 'un evanouissement reveilli.' [Google translate: a wakened fainting.]

Take 1 teaspoon black peppercorns, 1 whole nutmeg, 4 average sticks of cinnamon, 1 teaspoon coriander. These should all be pulverised in a mortar. About a handful each of stoned dates, dried figs, shelled almonds and peanuts: chop these and mix them together. A bunch of canibus sativa can be pulverised. This along with the spices should be dusted over the mixed fruit and nuts, kneaded together. About a cup of sugar dissolved in a big pat of butter. Rolled into a cake and cut into pieces or made into balls about the size of a walnut, it should be eaten with care. Two pieces are quite sufficient.

Obtaining the canibus may present certain difficulties, but the variety known as canibus sativa grows as a common weed, often unrecognised, everywhere in Europe, Asia and parts of Africa; besides being cultivated as a crop for the manufacture of rope. In the Americas, while often discouraged, its cousin, called canibus indica, has been observed even in city window boxes. It should be picked and dried as soon as it has gone to seed and while the plant is still green.

-- Haschich Fudge, from "The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book," by Alice B. Toklas

I love you Alice B. Toklas

And so does Gertrude Stein

I love you Alice B. Toklas

I'm going to change your name to mine

Red velvet trees and lions grinning lions

Candy witches eating lychee leaves spinning rainbowing light

Green lily golden gardens Marvin gardens

coriander baby elephants singing silent night

Sweet cinnamon and nutmeg shake the powder tell your teeth what [inaudible]

Clean cannabis sativa, sweet sativa chocolate melting so

I love you Alice B. Toklas

And so does Gertrude Stein

I love you Alice B. Toklas

I'm going to change your name to mine

I love you Alice B. Toklas

And so does Gertrude Stein

I love you Alice B. Toklas

[Nancy] I decided to split -- Made you some groovy brownies. Love, Nancy.

[Joyce] Look. Look, I found some brownies.

[Father] They look fresh baked.

[Mother] Do you have saccharine, Harold?

[Joyce] Oh, I have some in my purse.

[Mother] Oh, you're a darling. Thank you.

Well, looks like a nice brownie, Harold.

From Rubins?

[Harold] I don't remember.

A small bakery on Fairfax.

[Mother] Better than Rubins.

[Father] Better than Rubins? That's a brownie.

[Joyce] This is delicious.

[Harold] They're very good.

They're ...

They're groovy.

[Father] I wish Herbie was here with us now. He loves sweets.

[Joyce] Herbie is a very sweet boy. Do you know what I think?

I think that this is just a stage that he's going through, that's all.

[Mother] To a funeral he wears his Indian suit.

[Harold] Oh, these are really good.

[Joyce] Thank you.

[Father] One more.

[Mother] Ben.

[Father] My last one.

[Mother] All right.

[Mother] Ben.

Benjie.

What was his name?

What was his name, your cousin from Milwaukee?

You know what he did?

[Harold] What did he do?

[Mother] He came out of the bathroom.

[Joyce] What did he do when he came out of the bathroom?

[Mother] Don't say bathroom and I won't laugh.

I said it!

[Joyce] Take me.

Take me.

[Mother] Remember? Remember?

[Joyce] Oh, Harold, take me.

Harold.

[Father] I wanna play miniature golf.

***

[Joyce] Where's Harold?

***

[Anita] You know, I just can't. I've tried. I can't take the pills.

I blow up like a house.

It's really such a drag. These pills are so groovy.

But a diaphragm, forget it. It's just the worse.

Listen, thanks for coming in.

[Nancy] Harold!

[Harold] Hey. Hi.

[Nancy] Harold, this is Anita.

[Anita] Oh, my God, you look just like a guy I used to go with.

[Harold] Yeah?

[Anita] You're a little better-looking.

[Harold] Oh, thanks.

[Anita] Nice.

[Harold] Um.

[Nancy] What?

[Harold] I came to thank you for the brownies.

[Nancy] You're welcome.

[Harold] I came to see you.

[Nancy] Groovy.

[Harold] Yeah. Groovy.

You're very pretty.

[Nancy] And so are you.

[Harold] Yeah?

You should've told me what was in those brownies.

[Nancy] Thank Alice B. Toklas. It's her recipe.

[Harold] Yeah?

[Nancy] She wrote a freaky cookbook.

[Harold] And she turned my parents into junkies.

[Nancy] She did?

[Harold] Oh, yeah.

They were --

[Nancy] Excuse me. I'll be right back.

Can I help you, sir?

[Man in Dress Shop] Yes.

I'd like to see something in a minidress. Something lightweight.

[Nancy] These just came in. What size does she wear?

[Man in Dress Shop] It's for me.

[Nancy] Well, I don't know if we happen to have your size.

[Man in Dress Shop] I'm a perfect 12.

[Nancy] These are 12's.

[Man in Dress Shop] Thank you.

[Harold] Don't look at me.

[Nancy] I think he wants it to go to a Halloween party.

[Harold] I hope so.

[Man in Dress Shop] Miss.

[Nancy] Did you find something you like?

[Man in Dress Shop] Yes.

Yes, I like this one. Is there any place I can try it on?

[Nancy] Right over there.

[Man in Dress Shop] Oh, thank you.

[Harold] I can't help it. I can't.

[Nancy] Have a cookie.

[Harold] Alice Toklas?

[Nancy] Chocolate chip.

[Man in Dress Shop] Miss?

[Nancy] Yes, sir. Yes, sir.

[Man in Dress Shop] Do you do alterations here in the shop?

[Nancy] Yes, we do. Anita!

[Man in Dress Shop] What I'd like to get would be to get this just about two inches shorter.

About like that.

[Nancy] Well, Anita does the alterations.

Anita, can we shorten this about --?

[Man in Dress Shop] No, that's it. Right there.

[Nancy] Two inches?

[Anita] No, no, no.

That's not your color.

***

[Nancy] I have a butterfly.

[Harold] I know.

It's a monarch, isn't it?

[Nancy] Yeah.

Yeah.

[Harold] I never got that close to a butterfly.

Wait a second.

[Mother] Hello, Harold?

[Harold] Yes, Ma.

[Mother] You sound like your asthma is worse.

[Harold] No, Mama, the earth just moved.

[Mother] So where did you disappear to?

Stop it.

Oh, listen, I changed my mind.

I'm not putting Aunt Tanya next to Uncle Murray.

She's got that bladder trouble, poor thing ...

... so I'm gonna put her closer to the door.

Listen, Harold, I picked up some of those --

Go to sleep.

I picked up some of those brownies. You know, it must be a different bakery.

Oh, they're terrible. Rubins is better than those.

So anyway, I ordered the Jello-O-mold.

It's gonna be a green Jell-o with cherries.

-- I Love You, Alice B. Toklas -- Illustrated Screenplay, directed by Hy Averback, written by Paul Mazursky & Larry Tucker

Hoernle states(55) that this formula, although with more ingredients and different proportions, occurs also in the Charaka VI and Âshtânga Hridaya IV. Hoernle(56) mentions that the eight drugs known to the ancients and now substituted are: 1. Jîvaka, 2. Rishabha, 3. Mêdâ, 4. Mahâmêdâ, 5. Kâkôlî, 6. Kshîra-kâkôlî, 7. Riddhi, 8. Vriddhi; 1 and 2: Root of Vidârî (Batatas paniculata [Ipomoea mauritania Jacq, (Convolvulaceae)]) 3 and 4: Roots of Śatâvarî (Asparagus racemosus [Asparagus racemosus Willd., (Asparagaceae)]) 5 and 6: Aśhvagandhâ (Withania somnifera [Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal, (Solanaceae)]), 7 and 8: Tubers of the Varâhî or Bhadramustra (Cyperus pertenuis [Cyperus articulatus L. or C. tenuiflorus Rottb., (Cyperaceae)]).

4.2. (II) The Amrita Oil (Hoernle, 2011, pp.: 106–107):

“(IV) The Amrita Oil,116 in 25 ślôka and 1 pâda. (287–312a.) The two truth-speaking Aśvins, the divine physicians, honoured by the Dêvas, have declared the following excellent health-promoting oil, (288) which relieves all diseases, is fit for a king, and is as good as ambrosia. It is known by the name of Amrita (or ‘ambrosia’), and is an oil able to make men strong. (289) At the time of Pushya117, after having said prayers118, performed purification rites, and asked the Brâhmans' blessing in a few words, take out liquorice-roots grown in a favourable place. (290) Of the fresh juice of these roots take four pâtra9, and add four pala each of the following drugs: Papaundarîka119 [a fragrant wood], Amritâ (Tinospora cordifolia) [Tinospora cordifolia (Thunb.) Miers, (Menispermaceae)], knots of lotus-stalks [Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., (Nelumbonaceae)], Śatâvarî (Asparagus racemosus) [Asparagus racemosus Willd., (Asparagaceae)], (291) Śringâtaka (Trapa bispinosa) [Trapa natans var. bispinosa (Roxb.) Makino, (Lythraceae)], emblic myrobalan [Phyllanthus emblica L., (Phyllanthaceae)], Undumbara (Ficus glomerata) [Ficus racemosa L., (Moraceae)], Kaśêruka (Scripus Kysoor) [Actinoscirpus grossus var. kysoor (Roxb.) Noltie, (Cyperaceae)], the bark of each of the (five) trees with a milky sap120 [Nyagrôdha (Ficus indica) [Ficus sp., (Moraceae)], Udumbara (Ficus glomerata) [Ficus racemosa L., (Moraceae)], Asvattha (Ficus religiosa) [Ficus religiosa L., (Moraceae)], Plaksha (Ficus infectoria) [Ficus sp., (Moraceae)], Pârîsha (Thespesia populnea) [Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa, (Malvaceae)], (292) roots of Kuśa (Poa cynosuroides) [Desmostachya bipinnata (L.) Stapf, (Poaceae)], Kâsa (Saccharum spontaneum) [Saccharum spontaneum L., (Poaceae)] and Ikshu (Saccharum officinarum) [S. officinarum L., (Poaceae)], also of Śara (Saccharum Sara) [Saccharum bengalense Retz., (Poaceae)] and Vîrana (Andropogon muricatus)121 [Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty, (Poaceae)], also roots of Gundrâ (Panicum uliginosum) [Sacciolepis interrupta (Willd.) Stapf, (Poaceae)], of Nadikâ122 [not identified] and of the lotus [N. nucifera], (293) Vadarî (Ziziphus Jujuba) [Z. jujuba], Vidârî (Ipomoea digitata) [I. cheirophylla], Vêtasa (Calamus Rotang) [Calamus rotang L., (Arecaeea)], Adurûshaka (Adhatoda vasica) [Adhatoda vasica Nees, unresolved (Acanthaceae)], Nîm [Azadirachta indica A. Juss., (Meliaceae)], Sâlmalî (Bombax malabaricum) [Bombax ceiba L., (Malvaceae)], dates [P. dactylifera], cocoanut [Cocos nucifera L., (Arecaceae)], Priyangu (Aglaia Roxburghiana) [Aglaia elaeagnoidea (A. Juss.) Benth., (Meliaceae)], (294) Patôla (Trichosanthes dioica) [unresolved ev. Mukia maderaspatana (L.) M.Roem, (Cucurbitaceae)], Kutaja (Holarrhena antidysenterica) [Wrightia antidysenterica (L.) R.Br. or Holarrhena pubescens Wall. ex G. Don, (Apocynaceae)], raisins [Vitis sp.], leaf-stalk of the lotus [N. nucifera], sandal [Santalum sp., (Santalaceae)], Kakubha (Terminalia Arjuna) [Terminalia arjuna (Roxb. ex DC.) Wight & Arn., (Combretaceae)], Aśvakarna (Shorea robusta) [Shorea robusta Gaertn., (Dipterocarpaceae)], Lâmajjaka (Adropogon laniger) [Cymbopogon jwarancusa subsp. olivieri (Boiss.) Soenarko, (Poaceae)], and plumbago-root [Plumbago zeylanica L., (Plumbaginaceae)], (295) also other astringent, sweet or cooling drugs, as many as may be obtainable. Boil all these in two drôna of water, (296) and when the whole is reduced to one-eight of the original quantity, boil in it pastes made of fine powder of one pala each of the following drugs: Balâ (Sida cordifolia) [Sida cordifolia L., (Malvaceae)], Nâgabalâ (Sida spinosa) [Sida spinosa L., (Malvaceae)], Jîvâ (Dendrobium multicaule) [Conchidium muscicola (Lindl.) Rauschert, (Orchidaceae)], cowhage [M. pruriens], Kasêruka (Scirpus Kysoor) [A. grossus var. kysoor], (297) Nata (Tabernaemontana coronaria) [Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., (Apocynaceae)], juice of sugar-cane123, Sprikkà (Trigonella corniculata) [Trigonella balansae Boiss. & Reut., (Fabaceae)], small cardamoms [E. cardamomum] and cinnamon-bark [Cinnamomum sp., (Lauraceae)], Jîvaka56 [unknown and substituted] Rishabhaka56 [unknown and substituted] Mêdâ56 [unknown and substituted], Madhuka (Bassia latifolia) [M. longifolia var. latifolia, (Sapotaceae)], and blue lotus [Nymphaea nouchali var. caerulea (Savigny) Verdc., (Nymphaeaceae)] (298), the colour producing saffron [Crocus sativus L., (Iridaceae)], aloe-wood [Aquilaria sp., (Thymelaeaceae)], and cinnamon-leaves [Cinnamomum sp.], Vidârî (Ipomoea digitata) [I. cheirophylla], Kshîrakakôlî63 [said to be unknown], Vîrâ (Uraria lagopoides) [Uraria lagopodoides (L.) DC., (Fabaceae)], and Śârivâ (Ichnocarpus frutescens) [Ichnocarpus frutescens (L.) W.T. Aiton, (Apocynaceae)], (299) Śatâvarî (Asparagus racemosus) [A. racemosus], Priyangu (Aglaia Roxburghiana) [A. elaeagnoidea], Gudûchî (Tinospora cordifolia) [Tinospora cordifolia], filaments of the lotus [N. nucifera], Lâmajjaka (Andropogon laniger) [C. jwarancusa subsp. olivieri], red and white sandal [Santalum spp.], and fruits of Râjâdana (Mimusops hexandra) [Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard or Mimusops coriacea (A.DC.) Miq., (Sapotaceae)], (300) pearl, coral, conch-shell, moon-stone, sapphire, crystal, silver, gold, and other gems and pearls, (301) liquorice [G. glabra], madder [Rubia tinctorum L., (Rubiaceae)], and Amśumatî (Desmodium gangeticum) [Desmodium gangeticum]. Boil the whole slowly over a gentle fire (302) with four pâtra of (sweet) oil and eight times as much of milk, adding also tamarind juice [Tamarindus indica L., (Fabaceae)] and vinegar of rice124 one half as much as the milk. (303) This boiling should be repeated a hundred or even a thousand times; and when it is thoroughly done, it may be known by this sign, (304) that on the approach of the proper time the oil stiffens by exposure to the rays of the sun.125 After asking the Brâhmans’ blessing, performing purificatory rites and saying prayers, (305) this Amrita (or ‘ambrosial’) oil, highly esteemed by the Dêvas, may be administered to the patient, in the form of an injection per anum or per urethram,110 or as a draught, or an errhine, or a liniment.

(306) It serves the purpose of relieving disease and imparting strength to the organs of sense. For those who suffer from morbid heat and thirst it makes an excellent and beneficial liniment. (307) It promotes the growth of the hair in the old and that of the body in the young; it produces loveliness and grace in women; and also ensures numerous offspring, (308) for, by the use of this ambrosial oil, women are predisposed to conception. It cures the eighty nervous diseases109, also those due to derangement of the blood or the bile (309) or the phlegm or all the humours concurrently.126 By its use as an errhine or a liniment the eyes become as sharp as those of an eagle. (310) It keeps of calamities, averts all fortune, and promotes prosperity. By the use of this oil the Maharshi Chyavana92 regained (311) his youth, and was delivered from decrepitude and disease; and the blessed Maharshi Mârkandêya127, who was desirous of a long life, (312a) obtained his desire by the regular use of this oil.”

Hoernle(116) was not able to find this formula elsewhere and notes that it is a “phenomenally long one” containing 83 ingredients. Hoernle(9) gives some explanations on the measures and states that pâtra is also called âdhaka. Paramhans (1984) explains the medieval Indian weight measurement system as follows: 2 pala = 1 prasrti, 2 prasrtis = 1 añjali or kudava, 2 añjalis = 1 śaravâ, 2 śaravâs = 1 prastha, 4 prasthas = 1 âdhaka, 4 âdhakas = 1 drôna. Since over the course of time the overall mass changed but the proportions within the Indian weight measurement system remained the same, a translation into Western weight equivalents makes no sense.

5. Theoretical frame of the research question

What at first sight caught our attention were the names of the two recipes along with the description of “good as ambrosia” or “ambrosia-like elixir”. ‘Amrita’ means ‘immortality’ and is a synonym of Soma, ‘Amrita-prâsa’ means ‘food of the immortals’ and ‘ambrosia’ can be translated as ‘food of the gods’ or ‘nectar’. While we use here Amrita as a synonym of Soma, nothing about the description of the recipes, not even the therapeutic indications, suggest or allude to any exhilarating, intoxicating or psychoactive property of ‘Amrita clarified butter’ or ‘Amrita oil’. However, the ‘Amrita oil’ is also said to cure “the eighty nervous diseases” (p.: 107). As further reading on the ethnomedical concept of nervous diseases Hoernle(119) indicates the commentary on the Hindu system of medicine by Wise (1845) as well as the Bhâva Prakâśa and the Charaka Samhitâ, both edited by Pandit Jibananda V. at Calcutta in 1875 and 1877, respectively. Due to external forces (e.g. dryness, cold, light types of food, wet cloths), physical overstraining (e.g. excessive sexual practice, improper exercise) or psychological reasons (too much thinking, sorrow, grief, fear, anger) air is deranged, which causes different kind of symptoms, such as: “persons speak nonsense”, “affected parts shake”, “pain in the chest, head and temples”, body is “bent like a bow”, “spasmodic convulsions”, “difficulties in breathing”, “person cannot speak”, “dyspepsia and drowsiness”, “trembling and shivering”, “head is always shaking” (Wise, 1845, pp.: 250–258). Moreover, ‘Amrita-prâsa’ as well as ‘Amrita oil’ are said to relieve all diseases and to “increase the strength of men” or “make men strong”. The term ‘men’ in the text evidently refers to men and women since the Amrita oil is reported to produce “loveliness and grace in women” and to predispose women to conception.

The original Soma rite, central to which was the taking of a psychoactive Soma potion conferring the participants a god-like perspective, came into disuse but neither is it clear when exactly the Soma rite was abandoned nor what was its cause or reason. Besides the cultural transition taking place towards the end of the Rigvedic period, neurotoxic side effects of the Soma potion might have conditioned the loss of the Soma rite. A Soma (Amrita) recipe written down in the 6th century A.D., around 1800 years after the demise of the Rigvedic period can be expected to have received modifications in its formulation as well as in its medico-therapeutic application. The evolution of the Amrita recipes possibly affected the number of ingredients, proportions, overall indications and therapeutic use as well as the medico-philosophical frame. Although the evolution of these aspects evades a closer scientific analysis we argue that if these two recipes are derivatives of an ancient Soma formulation (or formulations), the core species required for the induction of a psychoactive effect should, eventually in smaller proportions, be present among the ingredients. In more general terms we argue that the Soma plant(s), so central to the Indo-Aryan culture, did not vanish from the Indian herbal scenery but linger on in herbal medicine as genuine medicinal plants.

6. Research questions

(i) Are there plant species among the ingredients of the two recipes able, either in combination or alone, to induce mind-altering effects upon ingestion?

(ii) If so, is the concentration of central nervous system (CNS) active compounds in the species under examination sufficient in order to induce perceivable pharmacologic effects? i.e. is the processing and practical application of the quantity of (crude) drugs needed to induce perceivable pharmacologic effects feasible? This includes that the potentially psychoactive constituents should not only be present at physiologically relevant amounts in the plant material but also be bio-available and extractable with water or an emulsion such as milk in reasonable quantities. Moreover, should a suggestion that makes practical sense also consider bio-geography and the theoretical availability of the species in the region of the Punjab.

(iii) A more specific question relates to the pharmacology of the formulations and if they contain monoamine oxidase (MAO) substrates and/or MAO inhibitors (MAO-I):

Are there neurotransmitter mimicking MAO substrates (possibly easy extractable alkaloids) as well as secondary metabolites able to interrupt the catabolic MAO pathways present in the species listed among the ingredients of recipe I and II?

The pharmacologic potentiation resulting from a combination of tryptamines with MAO inhibiting -carbolines has been described for South American snuffs (Holmstedt and Lindgren 1967, p.: 365) and Ayahuasca (Callaway et al., 1999). Such a potentiation of pharmacologic effects can theoretically also be achieved with the -carboline containing Peganum harmala seeds (see theory put forward by Flattery and Schwartz for Haoma).

7. Results

7.1. Analysis of the two recipes

A comparison of the ingredients of the two recipes shows that only few species make part of both formulations namely: Asparagus racemosus, Phyllanthus emblica, Ipomoea cheirophylla, Mucuna pruriens, Sida spinosa, Sida cordifolia, Madhuca longifolia, Uraria lagopodoides and Desmodium gangeticum. Species with potentially psychoactive metabolites detected in recipe (I) are: Sida spinosa, Sida cordifolia, Sida rhombifolia, Mucuna pruriens and Desmodium gangeticum. An analysis of recipe (II) revealed the following species with potentially psychoactive metabolites: Sida spinosa and Sida cordifolia, Mucuna pruriens, Desmodium gangeticum, Nelumbo nucifera, Tinospora cordifolia, Tabernaemontana divaricata. Neither Ephedra spp. nor Peganum harmala have been identified by Hoernle (2011) among the different recipes reported in the BM. Notably, the recipes do not contain any clear indication regarding the dose at which the mixtures should be applied for the treatment of the various health conditions and purposes for which they are recommended.

7.2. Species with potentially psychoactive metabolites detected in recipes I and II and their main constituents

7.2.1. Desmodium gangeticum (Fabaceae)

Desmodium gangeticum is a prostrate to sub-erect perennial weed growing throughout the Indian subcontinent in hilly areas up to 1500 m a.s.l. Under favourable conditions the plant can reach several metres in height (Ramakrishnan, 1964). The herb is called ‘salpan’ or ‘salpani’ in Hindi and ‘shalaparni’, ‘amśumatî’ or ‘vidârigandhâ’ in Sanskrit and is an important medicinal species within the Ayurvedic system of medicine (Hoernle, 2011; Rastogi et al., 2011). Chemical evaluations of above and below-ground tissues of Desmodium gangeticum by Banerjee and Ghosal (1969), as well as by Ghosal and Bhattacharya (1972) revealed the presence of different -phenethylamines (2-phenylethylamine (PEA, 1), hordenine (2), N-methyltyramine (3), candicine (4), N,N-dimethyl-2-oxo-2-phenylethylamine (5)), indolylalkylamines (N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT, 6) and its Nb-oxide, 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeODMT, 7) and its Nb-oxide and hypaphorine (8)) and -carbolines (6-methoxy-2-methyl- -carbolinium cation (9) and 1,2-dimethyl-2,3,4, 9-tetrahydro-1H- -carboline (1,2-Me-THBC, 10)).

From 1 kg fresh above ground plant material Banerjee and Ghosal (1969) obtained the following quantities of alkaloids: From the aqueous acidic extract (derived from the extracted chloroform layer) basified with ammonia and extracted with chloroform: 5-MeO-DMT (570 mg), DMT (not quantified), DMT-Nb-oxide (210 mg) and 5-MeO-DMT-Nb-oxide (180 mg). The chloroform soluble acetates were identified as Nb-methyltetrahydroharman (1,2-Me-THBC, 30 mg), DMT (410 mg) and DMT-Nb-oxide (120 mg), while from the aqueous mother liquor 210 mg of 6-methoxy-2-methyl- -carbolinium cation was obtained. Altogether more than 1730 mg of alkaloids were extracted from 1 kg of fresh plant material and Banerjee and Ghosal (1969) note that dried plant material contains higher proportions of 5-MeO-DMT with respect to fresh material.

7.2.2. Mucuna pruriens (Fabaceae)

Mucuna pruriens is an annual herb growing throughout the Indian plains and cultivated as a vegetable and fodder called ‘kavach’ in Hindi and ‘atmagupta’ or ‘vanari’ in Sanskrit (Williamson, 2002; Misra and Wagner, 2004). The seeds of Mucuna pruriens contain high amounts of L-DOPA (L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, 11). Mahajani et al. (1996) quantified the L-DOPA content of 10 g dried Mucuna pruriens seeds at around 330 mg, while Raina and Khatri (2011) found L-DOPA concentration in dried seeds of different accessions to vary considerably from 2.2 to 5.3% of dry weight. From the pods, seeds, leaves and roots several indole-3-alkylamines including DMT (6), DMTNb- oxide, bufotenine (5-OH-DMT, 12), 5-MeO-DMT (7), two not closer characterised 5-oxyindole-3-alkylamines and one -carboline were isolated (Ghosal et al., 1971). Misra and Wagner (2004) furthermore report on the isolation of four 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids (13-16, 94 mg altogether) from 500 g dried seeds.