by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/25/22

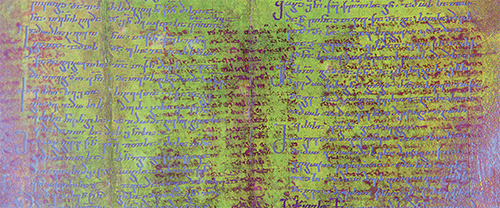

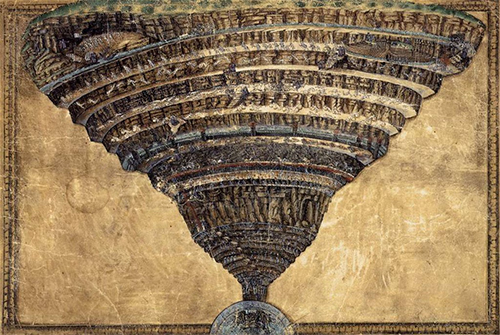

An image of Dionysius of Halicarnassus from the Codices Ambrosiani.

Born: c. 60 BC, Halicarnassus, Asia, Roman Republic (now Bodrum, Muğla, Turkey)

Died: c. 7 BC (aged around 53), Rome, Roman Empire (now Rome, Italy)

Citizenship: Roman

Occupation: Historian; Rhetoric; Writer

Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Ancient Greek: Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς, Dionúsios Alexándrou Halikarnasseús, ''Dionysios (son of Alexandros) of Halikarnassos''; c. 60 BC – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus.[1] His literary style was atticistic – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

Dionysius' opinion of the necessity of a promotion of paideia within education, from true knowledge of classical sources, endured for centuries in a form integral to the identity of the Greek elite.[2]

Life

He was a Halicarnassian.[2] At some time after the end of the civil wars he moved to Rome, and spent twenty-two years studying Latin and literature and preparing materials for his history.[3] During this period, he gave lessons in rhetoric, and enjoyed the society of many distinguished men. The date of his death is unknown.[4] In the 19th century, it was commonly supposed that he was the ancestor of Aelius Dionysius of Halicarnassus.[5]

Works

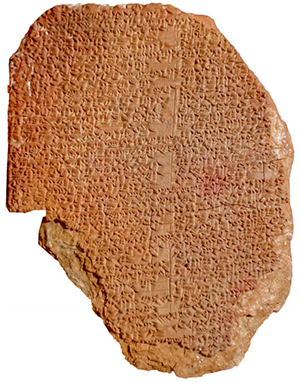

His major work, entitled Rhōmaïkḕ Arkhaiología (Ῥωμαϊκὴ Ἀρχαιολογία, ''Roman Antiquities''), narrates the history of Rome from the mythical period to the beginning of the First Punic War in twenty books, of which the first nine remain extant while the remaining books only exist as fragments,[3] in the excerpts of the Roman emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus [6 June 913 – 9 November 959; (1,000 YEARS LATER!)] and an epitome [An abridgment; a brief summary or abstract of a subject, or of a more extended exposition of it; a compendium containing the substance or principal matters of a book or other writing.] discovered by Angelo Mai in a Milan manuscript.

'Ambr': A collection of miscellaneous excerpts, in chronological order, in a 15th century Milan MS; also in a second MS which is a copy of it. The collection was carelessly edited by Cardinal Angelo Mai in 1816. MSS:-

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

Q / Milan, Ambrosian Library / Ambrosianus Q 13 sup. / 15th

A / Milan, Ambrosian Library / Ambrosianus A 80 sup. (Copy of Q) / ???

The order and location of the fragments can usually be determined, since Stephanus of Byzantium gives the books in which he found various people and places mentioned. However his references in books 17 and 18 are confused, so these are more uncertain.

-- Dionysius of Halicarnassus: the Manuscripts of "The Roman Antiquities", by Roger Pearse, tertullian.org, June 14, 2002

Angelo Mai (Latin Angelus Maius; 7 March 1782 – 8 September 1854) was an Italian Cardinal and philologist. He won a European reputation for publishing for the first time a series of previously unknown ancient texts. These he was able to discover and publish, first while in charge of the Ambrosian Library in Milan and then in the same role at the Vatican Library. The texts were often in parchment manuscripts that had been washed off and reused; he was able to read the lower text using chemicals. [NO CITATIONS!]

In particular he was able to locate a substantial portion of the much sought-after De republica of Cicero and the complete works of Virgilius Maro Grammaticus.

-- by Angelo Mai, by Wikipedia

Dionysius is the first major historian of early Roman history whose work is now extant. Several other ancient historians who wrote of this period, almost certainly used Dionysius as a source for their material. The works of Appian, Plutarch and Livy all describe similar people and events of Early Rome as Dionysius.[citation needed]

Summary outline of “Roman Antiquities”

In the preamble to Book I, Dionysius states that the Greek people lack basic information on Roman history, a deficiency he hopes to fix with the present work.

Book I (1300?)–753 BC

Mythic early history of Italy and its people. Book I also narrates the history of Aeneas and his progeny as well as Dionysius' telling of the Romulus and Remus myth, ending with the death of Remus.

Book II 753–673 BC

The Roman monarchy's first two Kings, Romulus and Numa Pompilius. Romulus formulates customs and laws for Rome. Sabine war -- as in subsequent parts of the history, this early conflict is described as involving numerous categories of officer, thousands of infantry, and cavalry combatants. This is highly unlikely, but is a common anachronism [An error in respect to dates; any error which implies the misplacing of persons or events in time; hence, anything foreign to or out of keeping with a specified time.] found in ancient historians.

Book III 673–575 BC

Kings Tullus Hostilius through Lucius Tarquinius Priscus.

Book IV 575–509 BC

Last of the Roman kings and end of the monarchy with overthrow of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.

Book V 509-497 BC

Start of Roman Republic and Consular years.

Book VI 496–493 BC

Includes the first instance of Plebeian secession.

Book VII 492–490 BC

This book describes at length the background leading to the Roman Coriolanus’ trial, ending in his exile. Much of the book is a debate between supporters of the oligarchy and the plebeians.

Book VIII 489–482 BC

Coriolanus, now exiled, allies with Rome’s current primary enemy, the Volscians. Coriolanus leads the Volscian army on a successful campaign against Roman allies and finally is near to capturing Rome itself. Coriolanus’ mother intercedes for the Roman state and manages to end the military campaign. Coriolanus then is treacherously murdered by the Volscians. The remaining part of the book covers the military campaigns to recover land from the Volscians.

Book IX 481–462 BC

Various military campaigns of mixed fortune in foreign matters. Domestically the plebeians and patricians argue and the conflict of the orders continues. The number of Tribunes is raised from 5 to 10. Book IX ends with the first two years of the decemvirate and the creation of the first Roman Law Tables.

Note

Manuscripts - books 1-10.

These were used by Jacoby for books 1-10:

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date-Century

A / ??? / Chisanus 58 / 10th century

B / Rome, Vatican / Urbinas 105 / 10th-11th century

C / ??? / Coislinianus 150 (also contains book 11 - see below) / 16th

D / Paris, BNF / Regius Parisinus 1654 & 1655 / 16th

E / Rome, Vatican / Vaticanus 133 (also contains book 11 = 'V' below) / 15th

F / Rome, Vatican / Urbinas 106 (contains books 1-5 only) / 15th

A and B are the best MSS - the others are all late and some, particularly C and D, contain numerous interpolations [the insertion of new words or expressions in a book or manuscript; especially, the falsification of a text by spurious or unauthorized insertions]. The editio princeps [The first printed edition of a book] was based on D. Jacoby felt a sound text should be based on A and B, and he used the late MSS hardly at all.

Manuscripts - books 1-10.

Those used for Kiessling and Jacoby for book 11:

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

L / Florence, Laurentian / Laurentianus Plut. LXX 5 / 15th

V / Rome, Vatican / Vaticanus 133 (= 'E' above) / 15th

M / Milan, Ambrosian / Ambrosianus A 159 sup. / 15th

C / ??? / Coislinianus 150 (= 'C' above) / 16th

The best of these four MSS is L, which appears to be a faithful copy of a badly damaged original; the scribe usually left gaps of appropriate length where he found the text illegible. Second best is 'V', which only occasionally shows interpolations; but this is the same MS labelled 'E' for the first ten books and treated as a negligible witness for them. Much inferior, however, even to 'V' are M and C, which show many unskilful attempts to correct the text, especially by filling lacunae [gaps], especially in chapters 42 and 48-49.

All these MSS derive from a poor archetype [manuscript] which, in addition to numerous shorter lacunae [gaps], had lost entire leaves at the end of book 11, as well as earlier, and had some of the remainder out of order.

-- Dionysius of Halicarnassus: the Manuscripts of "The Roman Antiquities", by Roger Pearse

The last ten books are fragmentary, based on excerpts from medieval Byzantine history compilations. Book XI is mostly extant at around 50 pages (Aeterna Press, 2015 edition), while the remaining books, have only 12–14 pages per book.

Book X 461–449 BC

The decemvirate continued.

Book XI 449–443 BC

fragments

Book XII 442–396 BC

fragments

Book XIII 394–390 BC

fragments

Book XIV 390 BC

Gauls sack of Rome.

Book XV

First and Second Samnite War.

Book XVI–XVII

Third Samnite War.

Book XIX

The beginnings of conflicts between Rome and the warlord Pyrrhus. The southern Italian city of Tarentum has problems with Rome, who have recently expanded into southern Italy. Tarentum invites Pyrrhus as muscle to protect them.

Book XX

Roman-Pyrrhic war, with Pyrrhus’s second invasion of Italy.

Because his prime objective was to reconcile the Greeks to Roman rule, Dionysius focused on the good qualities of their conquerors, and also argued that -– based on sources ancient in his own time -– the Romans were genuine descendants of the older Greeks.[6][7] According to him, history is philosophy teaching by examples, and this idea he has carried out from the point of view of a Greek rhetorician. But he carefully consulted the best authorities, and his work and that of Livy are the only connected and detailed extant accounts of early Roman history.[8]: 240–241

Dionysius was also the author of several rhetorical treatises, in which he shows that he had thoroughly studied the best Attic models:

Τέχνη ῥητορική, (Tékhnē rhētorikḗ)

The Art of Rhetoric

which is rather a collection of essays on the theory of rhetoric, incomplete, and certainly not all his work;

Περὶ συνθέσεως ὀνομάτων, (Perì sunthéseōs onomátōn) Latin: De compositione verborum

The Arrangement of Words

treating of the combination of words according to the different styles of oratory;

Περὶ μιμήσεως, (Perì mimḗseōs)

On Imitation

on the best models in the different kinds of literature and the way in which they are to be imitated—a fragmentary work;

Περὶ τῶν Ἀττικῶν ῥητόρων, (Perì tôn Attikôn rhētórōn)

Commentaries on the Attic Orators

which, however, only covers Lysias, Isaeus, Isocrates, and by way of supplement, Dinarchus;

Περὶ λεκτικῆς Δημοσθένους δεινότητος, (Perì lektikês Dēmosthénous deinótētos)

On the Admirable Style of Demosthenes

Περὶ Θουκιδίδου χαρακτῆρος, (Perì Thoukidídou kharaktêros)

On the Character of Thucydides

The last two treatises are supplemented by letters to Gn. Pompeius and Ammaeus (two, one of which is about Thucydides).[4]

Dionysian imitatio

Main article: Dionysian imitatio

Dionysian imitatio is the literary method of imitation as formulated by Dionysius, who conceived it as the rhetorical practice of emulating, adapting, reworking, and enriching a source text by an earlier author.[9][10] It shows marked similarities with Quintilian’s view of imitation, and both may derive from a common source.[11]

Dionysius' concept marked a significant departure from the concept of mimesis formulated by Aristotle in the 4th century BC, which was only concerned with "imitation of nature" and not "imitation of other authors."[9] Latin orators and rhetoricians adopted Dionysius' method of imitatio and discarded Aristotle's mimesis.[9]

History in the Roman Antiquities, and the Foundation Myth

Dionysius carried out extensive research for his Roman history, selecting among authorities, and preserving (for example) details of the Servian Census.[8]: 239

His first two books present a unified account of the supposed Greek origin for Rome, merging a variety of sources into a firm narrative: his success, however, was at the expense of concealing the primitive Roman actuality (as revealed by archaeology).[8]: 241 Along with Livy,[12] Dionysius is thus one of the primary sources for the accounts of the Roman foundation myth, and that of Romulus and Remus, and was relied on in the later publications of Plutarch, for example. He writes extensively on the myth, sometimes attributing direct quotations to its figures. The myth spans the first 2 volumes of his Roman Antiquities, beginning with Book I chapter 73 and concluding in Book II chapter 56.[citation needed]

Romulus and Remus

Origins and survival in the wild

Dionysius claims that the twins, Romulus and Remus, were born to a vestal [In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals were priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth. The college of the Vestals was regarded as fundamental to the continuance and security of Rome. These individuals cultivated the sacred fire that was not allowed to go out. Vestals were freed of the usual social obligations to marry and bear children and took a 30-year vow of chastity in order to devote themselves to the study and correct observance of state rituals that were forbidden to the colleges of male priests.] named Ilia Silvia (sometimes called Rea), descended from Aeneas of Troy

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises [Anchises was a member of the royal family of Troy in Greek and Roman legend. He was a mortal lover of the goddess Aphrodite.] and the Greek goddess Aphrodite [Aphrodite is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess Venus. Aphrodite's major symbols include myrtles, roses, doves, sparrows, and swans. The cult of Aphrodite was largely derived from that of the Phoenician goddess Astarte, a cognate of the East Semitic goddess Ishtar, whose cult was based on the Sumerian cult of Inanna.] (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons of Ilus, founder of Troy), making Aeneas a second cousin to Priam's children (such as Hector and Paris). He is a character in Greek mythology and is mentioned in Homer's Iliad. Aeneas receives full treatment in Roman mythology, most extensively in Virgil's Aeneid, where he is cast as an ancestor of Romulus and Remus. He became the first true hero of Rome. Snorri Sturluson identifies him with the Norse god Vidarr of the Æsir.[2]

-- Aeneas, by Wikipedia

and the daughter of King Latinus [Latinus was a figure in both Greek and Roman mythology. He is often associated with the heroes of the Trojan War, namely Odysseus and Aeneas.] of the Original Latin tribes, thus linking Rome to Trojans and Latins both. Dionysius lays out the different accounts of her pregnancy and the twins' conception, but declines to choose one over the others.

Citing Fabius [In Roman mythology, Fabius was the son of Hercules and an unnamed mother.], Cincius [Lucius Cincius Alimentus (fl. about 200 BC) was a celebrated Roman annalist, jurist, and provincial official. He is principally remembered as one of the founders of Roman historiography, although his Annals has been lost and is only known from fragments in other works.], Porcius Cato [Marcus Porcius Cato (234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor, the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write history in Latin with his Origines, a now fragmentary work on the history of Rome. His work De agri cultura, a rambling work on agriculture, farming, rituals, and recipes, is the oldest extant prose written in the Latin language.], and Piso [???], Dionysius recounts the most common tale, whereby the twins are to be tossed into the Tiber; are left at the site of the ficus Ruminalis [The Ficus Ruminalis was a wild fig tree that had religious and mythological significance in ancient Rome. It stood near the small cave known as the Lupercal at the foot of the Palatine Hill and was the spot where according to tradition the floating makeshift cradle of Romulus and Remus landed on the banks of the Tiber. There they were nurtured by the she-wolf and discovered by Faustulus.]; and rescued by a she-wolf who nurses them in front of her lair (the Lupercal) before being adopted by Faustulus [In Roman mythology, Faustulus was the shepherd who found the infant Romulus (the future founder of the city of Rome) and his twin brother Remus along the banks of the Tiber River as they were being suckled by the she-wolf, Lupa. According to legend, Faustulus carried the babies back to his sheepfold for his wife Acca Larentia to nurse them. Faustulus and Acca Larentia then raised the boys as their own.].[13] Dionysius relates an alternate, "non-fantastical" version of Romulus and Remus' birth, survival and youth. In this version, Numitor [In Roman mythology, King Numitor of Alba Longa, was the maternal grandfather of Rome's founder and first king, Romulus, and his twin brother Remus. He was the son of Procas, descendant of Aeneas the Trojan, and father of the twins' mother, Rhea Silvia, and Lausus.] managed to switch the twins at birth with two other infants.[14] The twins were delivered by their grandfather to Faustulus to be fostered by him and his wife, Laurentia, a former prostitute. According to Plutarch, lupa (Latin for "wolf") was a common term for members of her profession and this gave rise to the she-wolf legend.

Falling out and Foundation of Rome

The twins receive a proper education in the city of Gabii, before eventually winning control of the area around where Rome would be founded. Dispute over the particular hill upon which Rome should be built, the Palatine Hill or the Aventine Hill for its strategic advantages saw the brothers fall out and Remus killed.

When the time came to actually construct the city of Rome, the two brothers disputed over the particular hill upon which Rome should be built, Romulus favoring the Palatine Hill and Remus favoring what later came to be known as Remoria (possibly the Aventine Hill). Eventually, the two deferred their decision to the gods at the advice of their grandfather. Using the birds as omens, the two brothers decided "he to whom the more favourable birds first appeared should rule the colony and be its leader."[15] Since Remus saw nine vultures first, he claimed that the gods chose him and Romulus claimed that since he saw a greater (the "more favorable") number of vultures, the gods chose him. Unable to reach a conclusion, the two brothers and their followers fought, ultimately resulting in the death of Remus. After his brother's death, a saddened Romulus buried Remus at the site of Remoria, giving the location its namesake.[16]

Before the actual construction of the city began, Romulus made sacrifices and received good omens, and he then ordered the populace to ritually atone for their guilt. The city's fortifications were first and then housing for the populace. He assembled the people and gave them the choice as to what type of government they wanted - monarchy, democracy, or oligarchy - for its constitution.[17] After his address, which extolled bravery in war abroad and moderation at home, and in which Romulus denied any need to remain in power, the people decided to remain a kingdom and asked him to remain its king. Before accepting he looked for a sign of the approval of the gods. He prayed and witnessed an auspicious lightning bolt, after which he declared that no king shall take the throne without receiving approval from the gods.

Institutions

Dionysus then provided a detailed account of the ‘Romulus’ constitution, most probably based on the work of Terentius Varro [???].[18] Romulus supposedly divides Rome into 3 tribes, each with a Tribune in charge. Each tribe was divided into 10 Curia, and each of those into smaller units. He divided the kingdom's land holdings between them, and Dionysus alone among our authorities insists that this was done in equal lots.[19] The Patrician class was separated from the Plebeian class; while each curiae was responsible for providing soldiers in the event of war.

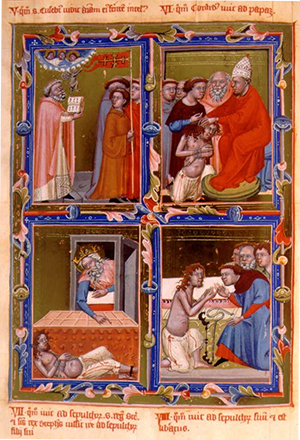

Bernard van Orley, Romulus Gives Laws to the Roman People – WGA16696

A system of patronage (clientela), a senate (attributed by Dionysius to Greek influence) and a personal bodyguard of 300 of the strongest and fittest among the nobles were also established: the latter, the celeres, were so-named either for their quickness, or, according to Valerius Antias, for their commander.[20]

A Separation of power and measures to increase manpower were also instituted, as were Rome's religious customs and practices, and a variety of legal measures praised by Dionysus.

Again, Dionysius thoroughly describes the laws of other nations before contrasting the approach of Romulus and lauding his work. The Roman law governing marriage is, according to his Antiquities, an elegant yet simple improvement over that of other nations, most of which he harshly derides. By declaring that wives would share equally in the possessions and conduct of their husband, Romulus promoted virtue in the former and deterred mistreatment by the latter. Wives could inherit upon their husband's death. A wife's adultery was a serious crime, however, drunkenness could be a mitigating factor in determining the appropriate punishment. Because of Romulus' laws, Dionysius claims that not a single Roman couple divorced over the following five centuries.

Romulus' laws governing parental rights, in particular, those that allow fathers to maintain power over their adult children were also considered an improvement over those of others; while Dionysius further approved of how, under the laws of Romulus, native-born free Romans were limited to two forms of employment: farming and the army. All other occupations were filled by slaves or non-Roman labor.

Romulus used the trappings of his office to encourage compliance with the law. His court was imposing and filled with loyal soldiers and he was always accompanied by the 12 lictors appointed to be his attendants.

The Rape of the Sabine Women and death of Romulus

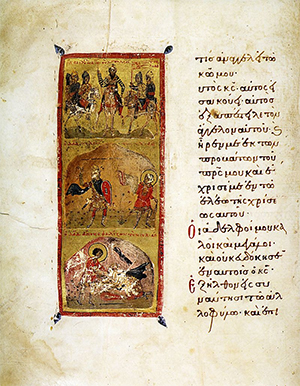

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, by Jacques-Louis David, 1799

Following his institutional account, Dionysus described the famous abducting of the Sabine women and suggesting thereby that the abduction was a pretext for alliance with the Sabines.[21] Romulus wished to cement relations with neighboring cities through intermarriage, but none of them found the fledgling city of Rome worthy of their daughters. To overcome this, Romulus arranged a festival in honor of Neptune (the Consualia) and invited the surrounding cities to attend. At the end of the festival, Romulus and the young men seized all the virgins at the festival and planned to marry them according to their customs.[22][23] In his narrative, however, the cities of Caecina, Crustumerium, and Antemnae petition for Tatius, king of the Sabines to lead them to war; and it is only after the famous intervention of the Sabine women that the nations agreed to become a single kingdom under the joint rule of Romulus and Tatius, both declared Quirites.[24]

The Rape of the Sabine Women... was an incident in Roman mythology in which the men of Rome committed a mass abduction of young women from the other cities in the region. It has been a frequent subject of painters and sculptors, particularly during the Renaissance and post-Renaissance eras.

The word "rape" (cognate with "rapto" in Portuguese and other Romance languages, meaning "kidnap") is the conventional translation of the Latin word raptio used in the ancient accounts of the incident. Modern scholars tend to interpret the word as "abduction" or "kidnapping" as opposed to a sexual assault....

According to Roman historian Livy, the abduction of Sabine women occurred in the early history of Rome shortly after its founding in the mid-8th century BC and was perpetrated by Romulus and his predominantly male followers; it is said that after the foundation of the city, the population consisted solely of Latins and other Italic people, in particular male bandits. With Rome growing at such a steady rate in comparison to its neighbors, Romulus became concerned with maintaining the city's strength. His main concern was that with few women inhabitants there would be no chance of sustaining the city's population, without which Rome might not last longer than a generation. On the advice of the Senate, the Romans then set out into the surrounding regions in search of wives to establish families with. The Romans negotiated unsuccessfully with all the peoples that they appealed to, including the Sabines, who populated the neighboring areas. The Sabines feared the emergence of a rival society and refused to allow their women to marry the Romans. Consequently, the Romans devised a plan to abduct the Sabine women during the festival of Neptune Equester....At the festival, Romulus gave a signal by "rising and folding his cloak and then throwing it round him again," at which the Romans grabbed the Sabine women and fought off the Sabine men. In total, thirty Sabine women were abducted by the Romans at the festival. All of the women abducted at the festival were said to have been virgins except for one married woman, Hersilia, who became Romulus' wife and would later be the one to intervene and stop the ensuing war between the Romans and the Sabines. The indignant abductees were soon implored by Romulus to accept the Roman men as their new husbands....

The Sabines themselves finally declared war, led into battle by their king, Titus Tatius. Tatius almost succeeded in capturing Rome, thanks to the treason of Tarpeia, daughter of Spurius Tarpeius, Roman governor of the citadel on the Capitoline Hill. She opened the city gates for the Sabines in return for "what they bore on their arms", thinking she would receive their golden bracelets. Instead, the Sabines crushed her to death with their shields, and her body was buried on or thrown from a rock known ever since by her name, the Tarpeian Rock.

The Romans attacked the Sabines who now held the citadel, in what would become known as the Battle of the Lacus Curtius....

At this point in the story, the Sabine women intervened:[They], from the outrage on whom the war originated, with hair dishevelled and garments rent, the timidity of their sex being overcome by such dreadful scenes, had the courage to throw themselves amid the flying weapons, and making a rush across, to part the incensed armies, and assuage their fury; imploring their fathers on the one side, their husbands on the other, "that as fathers-in-law and sons-in-law they would not contaminate each other with impious blood, nor stain their offspring with parricide, the one their grandchildren, the other their children. If you are dissatisfied with the affinity between you, if with our marriages, turn your resentment against us; we are the cause of war, we of wounds and of bloodshed to our husbands and parents. It were better that we perish than live widowed or fatherless without one or other of you."

The battle came to an end, and the Sabines agreed to unite in one nation with the Romans. Titus Tatius jointly ruled with Romulus until Tatius's death five years later.

The new Sabine residents of Rome settled on the Capitoline Hill, which they had captured in the battle.

-- The Rape of the Sabine Women, by Wikipedia

After the death of Tatius, however, Romulus became more dictatorial, until he met his end, either through actions divine or earthly. One tale tells of a "darkness" that took Romulus from his war camp to his father in heaven.[25] Another source claims that Romulus was killed by his Roman countrymen after releasing hostages, showing favoritism, and excessive cruelty in his punishments.[25]

Editions

• Collected Works edited by Friedrich Sylburg (1536–1596) (parallel Greek and Latin) (Frankfurt 1586) (available at Google Books)

• Complete edition by Johann Jakob Reiske (1774–1777)[26]

• Archaeologia by A. Kiessling (1860-1870) (vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4) and V. Prou (1886) and C. Jacoby (1885–1925) (vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4, supplementum) [26]

• Opuscula by Hermann Usener and Ludwig Radermacher (1899-1929)[26] in the Teubner series (vol. 1 contains Commentaries on the Attic Orators, Letter to Ammaeus, On the Admirable Style of Demosthenes, On the Character of Thucydides, Letter to Ammaeus about Thucydides, vol. 2 contains The Arrangement of Words, On Imitation, Letter to Gn. Pompeius, The Art of Rhetoric, Fragments)

• Roman Antiquities by V. Fromentin and J. H. Sautel (1998–), and Opuscula rhetorica by Aujac (1978–), in the Collection Budé

• English translation by Edward Spelman (1758) (available at Google Books)

• Trans. Earnest Cary, Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library:

o Roman Antiquities, I, 1937.

o Roman Antiquities, II, 1939.

o Roman Antiquities, III, 1940.

o Roman Antiquities, IV, 1943.

o Roman Antiquities, V, 1945.

o Roman Antiquities, VI, 1947.

o Roman Antiquities, VII, 1950.

• Trans. Stephen Usher, Critical Essays, I, Harvard University Press, 1974, ISBN 978-0-674-99512-3

• Trans. Stephen Usher, Critical Essays, II, Harvard University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0-674-99513-0

See also

• Diodorus Siculus

References

1. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book I, Chapter 6

2. Hidber, T. (31 Oct 2013). Wilson, N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 978-1136787997. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

3. Sandys, J.E. (1894). A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. London, GB. p. 190.

4. One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dionysius Halicarnassensis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 285–286.

5. Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Dionysius, Aelius". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston. p. 1037.

6. The Roman Antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. I. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. March 29, 2018 [1937] – via Penelope, U. Chicago.

7. Gabba, E. (1991). Dionysius and the History of Archaic Rome. Berkeley, CA.

8. Usher, S. (1969). The Historians of Greece and Rome. London, GB. pp. 239–241.

9. Ruthven (1979) pp. 103–104

10. Jansen (2008)

11. S F Bonner, The Literary Treatises of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (2013) p. 39

12. J Burrow, A History of Histories (Penguin 2009) p. 101 and 116

13. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book I, Chapter 79

14. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book I, Chapter 84

15. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book I, Chapter 85

16. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book I, Chapter 87

17. T P Wiseman, Remembering the Roman Republic (2011) p. xviii-ix

18. T P Wiseman, Remembering the Roman Republic (2011) p. xviii

19. T P Wiseman, Remembering the Roman Republic (2011) p. xviii

20. T P Wiseman, Remembering the Roman Republic (2011) p. ii

21. R Hexter ed., Innovations of Antiquity (2013) p. 164

22. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book II, Chapter 12

23. G Miles, Livy (2018) p. 197

24. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book II, Chapter 46

25. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities Book II, Chapter 56

26. Chisholm 1911.

Further reading

• Bonner, S. F. 1939. The literary treatises of Dionysius of Halicarnassus: A study in the development of critical method. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

• Damon, C. 1991. Aesthetic response and technical analysis in the rhetorical writings of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Museum Helveticum 48: 33–58.

• Dionysius of Halicarnassus. 1975. On Thucydides. Translated, with commentary, by W. Kendrick Pritchett. Berkeley and London: Univ. of California Press.

• Gabba, Emilio. 1991. Dionysius and the history of archaic Rome. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

• Gallia, Andrew B. 2007. Reassessing the 'Cumaean Chronicle': Greek chronology and Roman history in Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Journal of Roman Studies 97: 50–67.

• Jonge, Casper Constantijn de. 2008. Between Grammar and Rhetoric: Dionysius of Halicarnassus On Language, Linguistics and Literature. Leiden: Brill.

• Jonge, Casper C. de, and Richard L. Hunter (ed.). 2018. Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Augustan Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

• Sacks, Kenneth. 1986. Rhetoric and speeches in Hellenistic historiography. Athenaeum 74: 383–95.

• Usher, S. 1974–1985. Dionysius of Halicarnassus: The critical essays. 2 vols. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard Univ. Press.

• Wiater, N. 2011. The ideology of classicism: Language, history and identity in Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter.

• Wooten, C. W. 1994. The Peripatetic tradition in the literary essays of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. In: Peripatetic rhetoric after Aristotle. Edited by W. W. Fortenbaugh and D. C. Mirhady, 121–30. Rutgers University Studies in Classical Humanities 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

External links

Wikisource has original works by or about:

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Library resources about

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

________________________________________

• Online books

• Resources in your library

• Resources in other libraries

By Dionysius of Halicarnassus

• Online books

• Resources in your library

• Resources in other libraries

• English translation of the Antiquities (at LacusCurtius)

• 1586 Edition with the original Greek from the Internet Archive

• Greek text and French translation

****************************

Dionysius of Halicarnassus: the Manuscripts of "The Roman Antiquities"

by Roger Pearse

tertullian.org

June 14, 2002 Updated with book 11-20 details, 29th June 2002.

This work was written in 20 books, of which books 1-10 are preserved, with the greater part of book 11, and fragments of the remainder amounting altogether to about 1 book in size. Most of the fragments come from the great collection of historical extracts made at the direction of the emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the tenth century. Photius (cod. 83) refers to it, and also (cod. 84) to a summary of it in 5 books; Stephanus of Byzantium cites numerous Italian place-names from it, the last book named being book 19. The author was born between 69-53BC and died probably sometime after 7BC. The preface gives the date of publication as 7 BC (consulate of Nero and Piso), and he tells us in ch. 7 he spent 22 years researching and writing his work. The work treats in Greek of the History of Rome from earliest times down to the start of the First Punic War, the point at which the history of Polybius begins. The author also wrote other, shorter works, the scripta rhetorica of which only fragments remain.

Manuscripts - books 1-10.

These were used by Jacoby for books 1-10:

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date-Century

A / ??? / Chisanus 58 / 10th century

B / Rome, Vatican / Urbinas 105 / 10th-11th century

C / ??? / Coislinianus 150 (also contains book 11 - see below) / 16th

D / Paris, BNF / Regius Parisinus 1654 & 1655 / 16th

E / Rome, Vatican / Vaticanus 133 (also contains book 11 = 'V' below) / 15th

F / Rome, Vatican / Urbinas 106 (contains books 1-5 only) / 15th

A and B are the best MSS - the others are all late and some, particularly C and D, contain numerous interpolations [the insertion of new words or expressions in a book or manuscript; especially, the falsification of a text by spurious or unauthorized insertions]. The editio princeps [The first printed edition of a book] was based on D. Jacoby felt a sound text should be based on A and B, and he used the late MSS hardly at all.

Manuscripts - books 1-10.

Those used for Kiessling and Jacoby for book 11:

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

L / Florence, Laurentian / Laurentianus Plut. LXX 5 / 15th

V / Rome, Vatican / Vaticanus 133 (= 'E' above) / 15th

M / Milan, Ambrosian / Ambrosianus A 159 sup. / 15th

C / ??? / Coislinianus 150 (= 'C' above) / 16th

The best of these four MSS is L, which appears to be a faithful copy of a badly damaged original; the scribe usually left gaps of appropriate length where he found the text illegible. Second best is 'V', which only occasionally shows interpolations; but this is the same MS labelled 'E' for the first ten books and treated as a negligible witness for them. Much inferior, however, even to 'V' are M and C, which show many unskilful attempts to correct the text, especially by filling lacunae [gaps], especially in chapters 42 and 48-49.

All these MSS derive from a poor archetype [manuscript] which, in addition to numerous shorter lacunae [gaps], had lost entire leaves at the end of book 11, as well as earlier, and had some of the remainder out of order.

Manuscripts - fragments from books 12-20

About half of these come from the collection made by order of the Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the 10th century from then extant classical and later historians. The excerpts were classified under various heads, and a few of these sections have been preserved, some in only a single MS. These are the sections:

'Ursinus': De legationibus. There are several MSS. First published by Fulvio Orsini in 1582; critical edition by C. de Boor, Berlin 1903. MSS:-

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

E / Madrid, Escurial / Scorialenses R III 14, and R III 21 / ???

V / Rome, Vatican / Vaticanus Graecus 1418 / ???

R / Paris, BNF / Parisinus Graecus 2463 / ???

B / Brussels Bruxellensis 11301-16 / ???

M / ??? / Monacensis 267 / ???

P / Rome / Palatinus Vaticanus Graecus 113 / ???

'Vales': De virtutibus et vitiis. Preserved in the Codex Peirescianus (now Turonensis 980). Published by Valesius, 1634; critical edition by A.G. Roos, Berlin 1910. MSS:-

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

P / ??? / Peirescianus (now Turonensis 980) / ???

'Esc': De insidiis. Preserved in a single MS in the Escurial. Edited by Feder, 1848 and 1849, and by C. Müller in his Frag. Hist. Graec., vol. ii, 1848. critical edition by C. de Boor, Berlin 1903. MSS:-

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

S / ??? / Scorialensis W I 11 / ???

'Ath': A few chapters from book 20, contained in an early MS found on Mt. Athos but now in Paris. Edited by C. Müller at the end of vol 2 of his Josephus in 1847 and later by C. Wescher in his Poliorcétique des Grecs, Paris 1868. MSS:-

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

A / ??? / Athos MS, now in Paris / ???

'Ambr': A collection of miscellaneous excerpts, in chronological order, in a 15th century Milan MS; also in a second MS which is a copy of it. The collection was carelessly edited by Cardinal Angelo Mai in 1816. MSS:-

Siglum / Location / Shelfmark & Notes / Date - Century

Q / Milan, Ambrosian Library / Ambrosianus Q 13 sup. / 15th

A / Milan, Ambrosian Library / Ambrosianus A 80 sup. (Copy of Q) / ???

The order and location of the fragments can usually be determined, since Stephanus of Byzantium gives the books in which he found various people and places mentioned. However his references in books 17 and 18 are confused, so these are more uncertain.

Editions with new MS witnesses

The editio princeps of the Greek text was Robert Estienne (Stephanus), Paris, 1546. This contained books 1-11, and was based on D. Sylburg's edition of 1586 (Frankfurt) was books 1-11 plus the excerpta de Legationibus, with a revised version of Gelenius' Latin translation and notes. Sylburg made use of two MSS, a 'Romanus' (which has not been identified) and Venetus 272. John Hudson, Oxford 1704 had books 1-11, excerpta de Legationibus, and excerpta de Virtutibus et Vitiis. He was the first to use the Urbinas, which he called Vaticanus, but only in his notes.

Cardinal Angelo Mai published at Milan in 1816 some fragments from an epitome contained in a Milan MS, Cod. Ambrosianus Q 13 sup., and its copy, Cod. Ambrosianus A 80 sup. These are now included as the excerpta Ambrosiana among the fragments of books 12-20.

Translations with MS value

The first translation was into Latin of books 1-11 by Lapus (or Lappus) Biragus, Treviso 1480, three-quarters of a century before the first edition of the Greek text. It has great interest, since it was based on two MSS which cannot now be identified with any extant, supplied to the translator by Pope Paul II. Ritschl argued that one of these must have belonged to the better class of MSS, now known through A and B, as the translation contains most of the additions to the text of the editio princeps that are found in one or both of the older MSS. (Opuscula i, pp.489, 493). In addition he avoids most of B's errors, and includes down to III, 24 a good number of readings that appear in no other MS. Some of the interpolations in C and D are included, but he avoids most of C's interpolations. In a few cases he supplies words missing from both B and C, so his good MS must have been better than any now extant MS at these points. Since he refers to the confused order of the text at the end of book 11, his older MS cannot have been B; and the interpolated one can hardly have been C, if C is correctly assigned to the 16th century.

Gelenius did a fresh translation in 1549 of books 1-10; for 11 he merely reprinted Lapus's translation.

The only English translation before the Loeb was Edward Spelman, published London 1758 with notes and a dissertation. It is a good version of Hudson's text, and covers books 1-11, and served as the basis for the Loeb version.

Bibliography

Earnest CARY, The Roman antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Loeb edition in 7 vols. Harvard University Press (1937). Vol 1 has details of the MSS of books 1-X; Vol 7 (1950) about the MSS for book 11 and fragments of 12-20.

Carl JACOBY, Leipzig (Tuebner), 1885-1905, index 1925. (Details from the Loeb).

***************************

Biblioteca Ambrosiana

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/25/22

Entrance to the Ambrosian Library

Established: 1609

Location: Piazza Pio XI 2, 20123, Milan, Italy

Coordinates 45.4631°N 9.1854°ECoordinates: 45.4631°N 9.1854°E

Director: Alberto Rocca

Website: http://www.ambrosiana.it

The Biblioteca Ambrosiana is a historic library in Milan, Italy, also housing the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, the Ambrosian art gallery. Named after Ambrose, the patron saint of Milan, it was founded in 1609 by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, whose agents scoured Western Europe and even Greece and Syria for books and manuscripts. Some major acquisitions of complete libraries were the manuscripts of the Benedictine monastery of Bobbio (1606)

Bobbio Abbey (Italian: Abbazia di San Colombano) is a monastery founded by Irish Saint Columbanus in 614, around which later grew up the town of Bobbio, in the province of Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It is dedicated to Saint Columbanus. It was famous as a centre of resistance to Arianism and as one of the greatest libraries in the Middle Ages. The abbey was dissolved under the French administration in 1803, although many of the buildings remain in other uses.

-- Bobbio Abbey, by Wikipedia

and the library of the Paduan Vincenzo Pinelli, whose more than 800 manuscripts filled 70 cases when they were sent to Milan and included the famous Iliad, the Ilias Picta.

Gian Vincenzo Pinelli (1535 – 31 August 1601) was an Italian humanist, born in Naples and known as a savant and a mentor of Galileo. His literary correspondence put him at the center of a European network of virtuosi. He was also a noted botanist, bibliophile and collector of scientific instruments....

His enormous library was probably the greatest in 16th-century Italy, consisting of around 8,500 printed works at the moment of his death, plus hundreds of manuscripts. When he died, in 1601, Nicolas Fabri de Peiresc was in his house and spent some of the following months studying his library and taking notes from its catalogues. Pinelli's secretary, Paolo Gualdo, wrote and published (1607) a biography of Pinelli which is also the portrait of the perfect scholar and book-collector.

His collection of manuscripts, when it was purchased from his estate in 1608 for the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, filled 70 cases. Pinelli stood out among the early bibliophile collectors who established scientific bases for the methodically assembled private library, aided by the comparatively new figure—in the European world— of the bookseller.

His love of books and manuscripts, and his interest in optics, labored under a disability: a childhood mishap had destroyed the vision of one eye, forcing him to protect his weak vision with green-tinted lenses. Cautious and withdrawn by nature, detesting travel whether by road or canal boat, wracked by the gallstones that eventually killed him, he found solace in the library he amassed over a period of fifty years (Nuovo 2003).

Leonardo's treatise on painting, Trattato della Pittura, was transcribed in the Codex Pinellianus ca. 1585, perhaps expressly for Pinelli who made annotations in it. Pinelli's codex was the source for the Barberini codex from which it was eventually printed, ostensibly edited by Raphael du Fresne, in 1651. Pinelli's interest in the new science of optics was formative for Galileo Galilei, for whom Pinelli opened his library in the 1590s, where Galileo read the unpublished manuscripts, consisting of lecture notes and drafts of essays on optics, of Ettore Ausonio, a Venetian mathematician and physician, and of Giuseppe Moleto, professor of mathematics at Padua (Dupre).

Beside his Greek and Latin libraries of manuscripts his collection included the original Arabic manuscript from which was translated and printed the Descrizione dell'Africa of Leo Africanus.

-- Gian Vincenzo Pinellim by Wikipedia

History

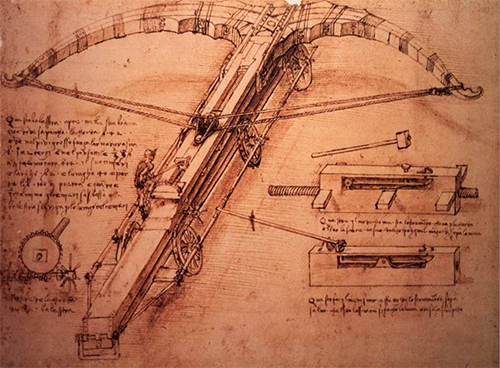

[Leonardo da Vinci Crossbow sketch, Codex Atlanticus

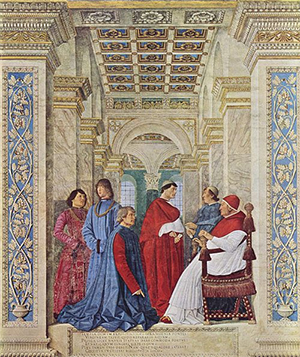

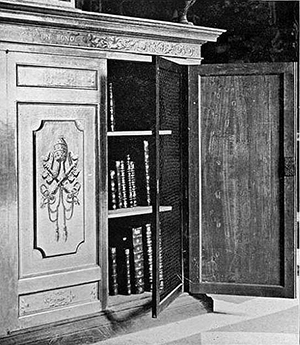

During Cardinal Borromeo's sojourns in Rome, 1585–95 and 1597–1601, he envisioned developing this library in Milan as one open to scholars and that would serve as a bulwark of Catholic scholarship in the service of the Counter-Reformation against the treatises issuing from Protestant presses. To house the cardinal's 15,000 manuscripts and twice that many printed books, construction began in 1603 under designs and direction of Lelio Buzzi and Francesco Maria Richini. When its first reading room, the Sala Fredericiana, opened to the public on 8 December 1609 it was one of the earliest public libraries. One innovation was that its books were housed in cases ranged along the walls, rather than chained to reading tables, the latter a medieval practice seen still today in the Laurentian Library of Florence. A printing press was attached to the library, and a school for instruction in the classical languages.

Constant acquisitions, soon augmented by bequests, required enlargement of the space. Borromeo intended an academy (which opened in 1625) and a collection of pictures, for which a new building was initiated in 1611–18 to house the Cardinal's paintings and drawings, the nucleus of the Pinacoteca.

Cardinal Borromeo gave his collection of paintings and drawings to the library, too. Shortly after the cardinal's death, his library acquired twelve manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci, including the Codex Atlanticus. The library now contains some 12,000 drawings by European artists, from the 14th through the 19th centuries, which have come from the collections of a wide range of patrons and artists, academicians, collectors, art dealers, and architects. Prized manuscripts, including the Leonardo codices, were requisitioned by the French during the Napoleonic occupation, and only partly returned after 1815.

Portrait of a Musician by Leonardo da Vinci

On 15 October 1816 the Romantic poet Lord Byron visited the library. He was delighted by the letters between Lucrezia Borgia and Pietro Bembo ("The prettiest love letters in the world"[1][2]) and claimed to have managed to steal a lock of her hair ("the prettiest and fairest imaginable."[2]) held on display.[3][4][5]

The novelist Mary Shelley visited the library on 14 September 1840 but was disappointed by the tight security occasioned by the recent attempted theft of "some of the relics of Petrarch" housed there.[6]

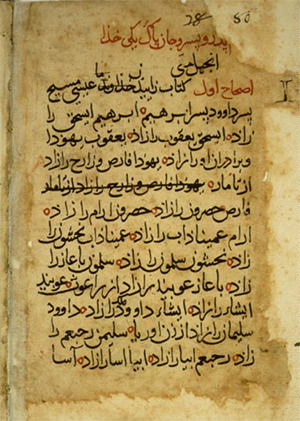

Among the 30,000 manuscripts, which range from Greek and Latin to Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic,[7] Ethiopian, Turkish and Persian, is the Muratorian fragment, of ca 170 A.D., the earliest example of a Biblical canon and an original copy of De divina proportione by Luca Pacioli. Among Christian and Islamic Arabic manuscripts are treatises on medicine, a unique 11th-century diwan of poets, and the oldest copy of the Kitab Sibawahaihi.

When looking at the secrets held within Vatican City, perhaps the most logical place to start is the Vatican Secret Archives. The name itself is evocative of mystery, and many theories have naturally arisen about what might be held among the 53 miles of shelves and 12 centuries' worth of documents only available to a select few....

[T]he Archives are not fully public: they're only open to scholars who have passed a rigorous vetting process, and journalists were not allowed to see the contents of the Archives until 2010.

-- Dark Secrets of the Vatican Revealed, by Benito Cereno, July 6, 2022

The library has a college of Doctors, similar to the scriptors of the Vatican Library. Among prominent figures have been Giuseppe Ripamonti, Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Giuseppe Antonio Sassi, Cardinal Angelo Mai and, at the beginning of the 20th century, Antonio Maria Ceriani, Achille Ratti (on 8 November 1888,[8][9] the future Pope Pius XI, and Giovanni Mercati. Ratti wrote a new edition of the Acta Ecclesiae Mediolanensis ("Acts of the Church of Milan"), Latin work firstly published by the cardinal Federico Borromeo in 1582.[9][8]

The building was damaged in World War II, with the loss of the archives of opera libretti of La Scala, but was restored in 1952 and underwent major restorations in 1990–97. The stained glass windows were made by the painter Carlo Bazzi and were partly saved from the Second World War.

Artwork at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana includes Leonardo da Vinci's "Portrait of a Musician", Caravaggio's "Basket of Fruit", Bramantino's Adoration of the Christ Child and Raphael's cartoon of "The School of Athens".

Some manuscripts

• Uncial 0135 — fragments of the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke

• Codex Ambrosianus 435, Ambrosianus 837 — treatise On the Soul of Aristotle

• Minuscule manuscripts of New Testament: 343, 344, 345, 346, 347, 348, 349, 350, 351, 352, 353, 614, 615

• Lectionaries ℓ 102, ℓ 103, ℓ 104, ℓ 105, ℓ 106, ℓ 284, ℓ 285, ℓ 286, ℓ 287, ℓ 288, ℓ 289, ℓ 290.

• Codices Ambrosiani, containing the Gothic language

References

1. Ian Thompson, review, The Spectator, 25 June 2005, of Viragos on the march by Gaia Servadio. I. B. Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-421-2.

2. Pietro Bembo: A Renaissance Courtier Who Had His Cake and Ate It Too, Ed Quattrocchi, Caxtonian: Journal of the Caxton Club of Chicago, Volume XIII, Nº. 10, October 2005.

3. The Byron Chronology: 1816–1819 – Separation and Exile on the Continent.

4. Byron by John Nichol.

5. Letter to Augusta Leigh, Milan, 15 October 1816. Lord Byron's Letters and Journals, Chapter 5: Separation and Exile Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

6. Shelley, Mary (1996). Travel Writing. London: Pickering. p. 132. ISBN 1-85196-084-8.

7. Oscar Löfgren and Renato Traini, Catalogue of the Arabic Manuscripts in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, vol. I (1975), ii (1981) onwards.

8. don Vincenzo Maraschi (Ambrosiane Doctor) (1938). Le Particolarità Del Rito Ambrosiano (in Italian). Milan. p. 1, 7, 174. Retrieved 10 April 2022., with imprimatur of Milan Curia (in person of friar Castiglioni) on 9 August 1938, and of cardinal Schuster

9. Carlo Marcora (1996). Achille Ratti and the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. persee.fr (in Italian and French). p. 56. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

Further reading

• Catalogus codicum graecorum Bibliothecae Ambrosianae (Mediolani 1906) Tomus I

• Catalogus codicum graecorum Bibliothecae Ambrosianae (Mediolani 1906) Tomus II

• Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Ambrosian Library" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

• Biblioteca Ambrosiana website, select English

• Ambrosiana Foundation, U.S. support organization

• Inventory Catalog of Drawings at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana

• http://www.1st-art-gallery.com/Edward-C ... tings.html

• "Ambrosian Library" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

External links

• Virtual tour of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana provided by Google Arts & Culture

• Media related to Biblioteca Ambrosiana at Wikimedia Commons