Many of the earliest of these literary products appear to have been codes of ascetic conduct; this is indeed a feature common to all ancient ascetical literature in India. Given that the main features of the renunciatory life are by and large uniform across all the traditions, it appears likely that these texts for the most part codified existent patterns of ascetic behavior, even though each sect modified them to suit its own needs and also included rules peculiar to it. An early example of such a code is the Buddhist Pratimoksa, a list of over 200 monastic rules.18 [For a discussion of the Pratimoksa and Buddhist monastic discipline, see S. Dutt, Early Buddhist Monachism. 2d ed. (London: Asia Publishing House, 1960); W. Pachow, "A Comparative Study of the Pratimoksa," The Sino-Indian Studies, VI(1951), pts. 1-2; C. S. Prebish, Buddhist Monastic Discipline: The Sanskrit Pratimoksa Sutras of the Mahasamghikas and Mulasarvastivadins (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1975).] It is also likely that early ascetic texts also included the rituals and ceremonies that accompanied the entry of a person into the ascetic life; initiation rites occupy a prominent position in the extant versions of these texts.

THE SPURIOUS BUDDHIST INSCRIPTIONS

According to the traditional analysis, the single most important putative "Asoka" inscription for the history of Buddhism is the unique "Third Minor Rock Edict" found at Bairat, now known as the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription,in which "the king of Magadha, Piyadasa" addresses the "Samgha" (community of Buddhist monks) directly, and gives the names of a number of Buddhist sutras, saying, "I desire, Sirs, that many groups of monks and (many) nuns may repeatedly listen to these expositions of the Dharma, and may reflect (on them)."

The problems with the inscription are many. It begins with the otherwise unattested phrase "The Magadha King Piyadasa", not Devanampriya Priyadarsi (or a Prakrit version of that name). The omission of the title Devanampriya is nothing short of shocking. Moreover, it is the only inscription to even mention Magadha. It is also undated, unlike the genuine Major Inscriptions, all of which are dated. In the text, the authorial voice declares "reverence and faith in the Buddha, the Dharma, (and) the Samgha".

This is the only occasion in all of the Mauryan inscriptions where the Triratna 'Three Jewels', the "refuge" formula well known from later devotional Buddhism, is mentioned. Most astonishingly, throughout the text the author repeatedly addresses the Buddhist monks humbly as bhamte, translated by Hultzsch as "reverend sirs". The text also contains a higher percentage of words that are found solely within it (i.e., not also found in some other inscription) than does any other inscription. From beginning to end, the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription is simply incompatible with the undoubtedly genuine Major Inscriptions. It is also evidently incompatible with the other Buddhist inscriptions possibly attributable to a later ruler named Devanampriya Asoka.

However, because the inscription is also the only putative Asokan inscription that mentions Buddhist texts, and even names seven of them explicitly, scholars are loath to remove it from the corpus. It therefore calls for a little more comment.

First, even if the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription really is "old", it is certainly much younger than the genuine inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarsi. If it dates to approximately the same epoch as the recently discovered Gandhari documents -- the Saka-Kushan period, from about the late first century BC to the mid-third century AD -- the same period when the Pali Canon, according to tradition, was collected, it should then not be surprising to find that the names of the texts mentioned in the inscription seem to accord with the contents of the latter collections of Normative Buddhist works, even though few, if any, of the texts (of which only the titles are given) can be identified with any certainty. [However, it must be borne in mind that the Trilaksana text discussed in Chapter One, though short, is by far the oldest known fragment of Buddhist text. It is thus possible that texts in the Pali Canon and the Gandhari documents that mention the Trilaksana might themselves be older than the other texts in the same corpora.]

Second, as noted above, specialists have pointed out that the script and Prakrit language of the Mauryan inscriptions continued to be used practically unchanged down through the Kushan period, and though the style of the script changed somewhat in the following period, it was still legible for any literate person at least as late as the beginning of the Gupta period (fourth century AD), so the inscriptions undoubtedly influenced the developing legends about the great Buddhist king, Asoka.

Thus at least some of the events described in the Major Inscriptions, such as Devanampriya Priyadarsi's conquest of Kalinga, subsequent remorse, and turning to the Dharma, were perfect candidates for ascription to Asoka in the legends. In the absence of any historical source of any kind on Asoka dating to a period close to the events -- none of the datable Major Inscriptions mention Asoka -- it is impossible to rule out this possibility. The late Buddhist inscriptions, such as the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription, may well have been written under the same influence.

Third, because the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription only mentions the titles of texts that have been identified -- rather uncertainly in most cases -- with the titles of texts in the Pali Canon, the actual texts referred to may have been quite different, or even totally different, from the presently attested ones. Because the earliest, or highest, possible date for the Pali Canon is in fact the Saka-Kushan period, the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription and the texts it names cannot be much earlier.

The inscription's list of "passages of scripture" that "Priyadarsi, King of Magadha" has selected to be frequently listened to by the monks so that "the True Dharma will be of long duration" is translated by Hultzsch as "the Vinaya-Samukasa, the Aliya-vasas, the Anagata-bhayas, the Munigathas, the Moneya-suta, the Upatisa-pasina, and the Laghulovada which was spoken by the blessed Buddha concerning falsehood."

Among the texts considered to be identified are the Vinaya-samukasa and the Muni-gatha.

The Vinaya-samukasa has been identified with the Vinaya-samukase 'Innate Principles of the Vinaya', a short text in the Mahavagga of the Pali Canon. After a brief introduction, the Buddha tells the monks what is permitted and what is not.

VINAYA-SAMUKASE

Now at that time uncertainty arose in the monks with regard to this and that item: "Now what is allowed by the Blessed One? What is not allowed?" They told this matter to the Blessed One, (who said):

"Bhikkhus, whatever I have not objected to, saying, 'This is not allowable,' if it fits in with what is not allowable, if it goes against what is allowable, this is not allowable for you.

"Whatever I have not objected to, saying, 'This is not allowable,' if it fits in with what is allowable, if it goes against what is not allowable, this is allowable for you.

"And whatever I have not permitted, saying, 'This is allowable,' if it fits in with what is not allowable, if it goes against what is allowable, this is not allowable for you.

"And whatever l have not permitted, saying, 'This is allowable,' if it fits in with what is allowable, if it goes against what is not allowable, this is allowable for you."

Although the Buddha's own speech in this text is structured as a tetralemma, which was fashionable in the fourth and third centuries BC, it must also be noted that the tetralemma is a dominant feature of the earliest Madhyamika texts, those by Nagarjuna, who is traditionally dated to approximately the second century AD. But the problems with the inscription are much deeper than this. The Vinaya per se cannot be dated back to the time of the Buddha (as the text intends), nor to the time of Asoka; it cannot be dated even to the Saka-Kushan period. All fully attested Vinaya texts are actually dated, either explicitly or implicitly, to the Gupta period, specifically to the fifth century AD: "In most cases, we can place the vinayas we have securely in time: the Sarvastivada-vinaya that we know was translated into Chinese at the beginning of the fifth century (404-405 C.E.). So were the Vinayas of the Dharmaguptakas (408), the Mahisasakas (423-424), and the Mahasamghikas (416). The Mulasarvastivada-vinaya was translated into both Chinese and Tibetan still later, and the actual contents of the Pali Vinaya are only knowable from Buddhaghosa's fifth century commentaries.

As Schopen has shown in many magisterial works, the Vinayas are layered texts, so they undoubtedly contain material earlier than the fifth century, but even the earliest layers of the Vinaya texts cannot be earlier than Normative Buddhism, which is datable to the Saka-Kushan period. It thus would require rather more than the usual amount of credulity to project the ancestors of the cited texts back another half millennium or more to the time of the Buddha.

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith

That this early ascetic literature should have focused on ascetic practice should come as no surprise, for in India throughout the ages proper conduct has counted for more than ideological purity. As we shall see (2.5), what a person did—and even where one did it—was considered inseparable from the broader issues of world view and religious ideology; indeed, the latter was often reducible to the former. Within Brahmanism itself, moreover, the bulk of the religious literature of this period was produced mostly for very practical reasons: either for the proper performance of Vedic or domestic rituals (the Srauta- and Grhya-sutras) or to inculcate proper personal and social behavior (the Dharma-sutras). Indeed, all the so-called ancillary Vedic texts (Vedangas) have very practical purposes.

Within Brahmanism itself the earliest literature with an ascetic thrust is found in the classical Upanisads. Passages with a strong ideological slant in favor of the ascetic worldview and way of life are found in the earliest of the Upanisads, such as the Brhadaranyaka and the Chandogya. Some of them will be examined in the next section. It is unclear, however, whether these passages were produced within ascetic institutions and later incorporated into the Upanisads or merely reflect the influence of ascetic ideologies on some segments of the ancient Vedic schools.

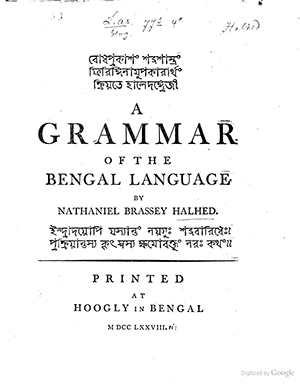

The earliest evidence we possess pointing to the existence of independent ascetical codes within the Brahmanical tradition comes from the grammatical treatise Astadhyayi of Panini, commonly assigned to the fourth century B.C.E. [LC: Then Panini did not live in either the 6th or 5th century B.C.E.] In explaining a particular type of derivative noun meaning "proclaimed by," Panini (IV.3.no—in) refers to the bhiksusutras—codes of conduct for mendicants—proclaimed by Parasarya and Karmandin.19 [For a detailed discussion of these, see Ajay Mitra Shastri, "The Bhiksusutra of Parasarya, "Journal of the Asiatic Society (Calcutta), 14, nos. 2—4(1972): 52— 59 (issued May 1975). I agree with Shastri that, despite some contradictory evidence from the poet Bana, Panini considered these ultras to have been Brahmanical works.] That these were not generic texts intended for all but codes that regulated the life of sociologically distinct groups of mendicants can be gathered from the reference to "Parasarin mendicants" (parasarino bhiksavah) as a distinct group by Patanjali, generally assigned to the second century B.C.E., in his commentary, Mahabhasya (IV.2.66), on Panini's grammar. This evidence, coming as it does from grammarians intent on finding examples for grammatical rules among words in common use, is historically very significant and certainly more reliable than any information we may find in the normative literature.

The most important single error made by almost everyone in Buddhist studies is methodological and theoretical in nature. In all scholarly fields, it is absolutely imperative that theories be based on the data, but in Buddhist studies, as in other fields like it, even dated, "provenanced" archaeological and historical source material that controverts the traditional view of Early Buddhism has been rejected because it does not agree with that traditional view, and even worse, because it does not agree with the traditional view of the entire world of early India, including beliefs about Brahmanism and other sects that are thought to have existed at that time, again based not on hard data but on the same late traditional accounts. Some of these beliefs remain largely or completely unchallenged, notably:

• the belief that Sramanas existed before the Buddha, so he became a Sramana like many other Sramanas

• the belief that there were Sramanas besides Early Buddhists, including Jains and Ajivikas, whose sects were as old or older than Buddhism, and the Buddha even knew some of their founders personally

• that, despite the name Sramana, and despite the work of Marshall, Bareau, and Schopen, the Early Buddhists were "monks" and lived in "monasteries" with a monastic rule, the Vinaya

• that, despite the scholarship of Bronkhorst, the Upanishads and other Brahmanist texts are very ancient, so old that they precede Buddhism, so the Buddha was influenced by their ideas

• that the dated Greek eyewitness reports on religious-philosophical practitioners in late fourth century BC India do not tally with the traditional Indian accounts written a half millennium or more later, so the Greek reports must be wrong and must be ignored

• perhaps most grievously, the belief that all stone inscriptions in the early Brahmi script of the Mauryan period were erected by "Asoka", the traditional grandson of the Mauryan Dynasty's historical founder, Candragupta, and whatever any of those inscriptions say is therefore evidence about what went on during (or before) the time he is thought to have lived ...

Here I quote a century-old summary that remains the received view:Jainism bears a striking resemblance to Buddhism in its monastic system, its ethical teachings, its sacred texts, and in the story of its founder. This closeness of resemblance has led not a few scholars -- such as Lassen, Weber, Wilson, Tiele, Barth -- to look upon Jainism as an offshoot of Buddhism and to place its origin some centuries later than the time of Buddha. But the prevailing view today -- that of Buhler, Jacobi, Hopkins, and others -- is that Jainism in its origin is independent of Buddhism and, perhaps, is the more ancient of the two. The many points of similarity between the two sects are explained by the indebtedness of both to a common source, namely the teachings and practices of ascetic, monastic Brahminism....

With regard to the idea that any kind of monasticism, least of all Brahmanist asceticism, could be the "common source", it may be noted that monasteries per se in India cannot be dated earlier than the first century AD, when they first appear in Taxila; they were introduced from Central Asia ...

Both Early Buddhism and Early Brahmanism are the direct outcome of the introduction of Zoroastrianism into eastern Gandhara by Darius I. Early Buddhism resulted from the Buddha's rejection of the basic principles of Early Zoroastrianism, while Early Brahmanism represents the acceptance of those principles....

Bronkhorst (2007: 358), remarks, "In the middle of the third century BC, it was Mazdaism, rather than Brahmanism, which predominated in the region between Kandahar and Taxila"....

In short, the Buddha reacted primarily (if at all) not against Brahmanism [Cf. Bronkhorst (1986; 2011: 1-4), q.v. the preceding note. From his discussion it is clear that even the earliest attested Brahmanist texts reflect the influence of Buddhism, so it would seem that the acceptance of Early Zoroastrian ideas in Gandhara happened later than the Buddhist rejection of them, but before the Alexander historians and Megasthenes got there in the late fourth century BC.] but against Early Zoroastrianism...

It is well established from the earliest accounts of Normative Buddhism that monks, nuns, and their monasteries were not taxed in ancient India.97 The ancient Greek accounts of Early Buddhism do not mention whether or not the Sramanas were taxed, but since they are explicitly described as living extremely frugally, it is difficult to imagine how they could have been taxed. The Forest-dwelling Sramanas, in particular, essentially owned nothing and had no property -- in fact, they did not participate in economic activity of any kind, as noted in Chapter Two -- while the Town-dwelling Sramanas, the Physicians, begged for their food and stayed with people who would put them up in their houses, so it would have been next to impossible to collect any taxes from them.98 [The Brahmanas, by contrast, had extensive possessions, including land, so one would imagine that they were taxed even during their ascetic stage, which according to Megasthenes was thirty-seven years long. The period is given as forty years in the accounts of Calanus, but he was not a Brahmanist at all, based on Megasthenes' description of the beliefs and practices of his sect; cf. the Epilogue. The insistence of modern scholars that Megasthenes' description does not accord with what "we know" about ancient Brahmanism is based not on ancient Brahmanism (of which we have absolutely no record for at least half a millennium after Megasthenes' time, and typically much longer), but on the imaginations of medieval to modern writers. Not only does Megasthenes present this as the normal state of affairs, the gymnosophistai 'naked wise-men' (or "Gymnosophists") of ancient Greek tradition -- who were neither Sramanas nor Brahmanas -- described in all accounts as having lived extremely frugally, and they openly encouraged the Greeks to join them and live the same way so as to learn their philosophy and practices....

Finally, the Delhi-Topra pillar includes a good version of the six synoptic Pillar Edicts, which are genuine Major Inscriptions, but it is followed by what is known as the "Seventh Pillar Edict". This is a section that occurs only on this particular monument -- not on any of the six other synoptic Pillar Edict monuments. It is "the longest of all the Asokan edicts. For the most part, it summarizes and restates the contents of the other pillar edicts, and to some extent those of the major rock edicts as well."70 In fact, as Salomon suggests, it is a hodgepodge of the authentic inscriptions. It seems not to have been observed that such a melange could not have been compiled without someone going from stone to stone to collect passages from different inscriptions, and this presumably must have involved transmission in writing, unlike with the Major Rock Edict inscriptions, which were clearly dictated orally to scribes from each region of India, who then wrote down the texts in their own local dialects -- and in some cases, their own local script or language; knowledge of writing would seem to be required for that, but not actual written texts.71 For the Delhi-Topra pillar addition, someone made copies of the texts and produced the unique "Seventh Pillar Edict".72 Why would anyone go to so much trouble? The answer is to be found in the salient new information found in the text itself. ... Most incredibly, the Buddhists are called the "Samgha" in this section alone, but it is a Normative Buddhist term; the Early Buddhist term is Sramana, attested in the genuine Major Inscriptions. Throughout the rest of the "Seventh Pillar Edict" Buddhists are called Sramanas, as expected in texts copied from genuine Mauryan inscriptions ...

Yet it is not only the contents of the text that are a problem. It has been accepted as an authentic Mauryan inscription, but no one has even noted that there is anything formally different about it from the other six edicts on the same pillar. At least a few words must therefore be said about this problem.

The "Seventh Pillar Edict" is palaeographically distinct from the text it has been appended to. It is obvious at first glance. The physical differences between the text of the "Seventh Pillar Edict", as compared even to the immediately preceding text of the Sixth Pillar Edict on the East Face, virtually leap out at one. The style of the script,76 the size and spacing of the letters, the poor control over consistency of style from one letter to the next,77 and the many hastily written, even scribbled, letters are all remarkable. These characteristics seem not to have been mentioned by the many scholars who have worked on the Mauryan inscriptions.

The text begins as an addition to the synoptic Sixth Pillar Edict, which occupies only part of the East Face "panel". After filling out the available space for text on the East Face, the new text incredibly continues around the pillar, that is, ignoring the four different "faces" already established by the earlier, genuine edicts. This circum-pillar format is unique among all the genuine Mauryan pillar inscriptions.78

Another remarkable difference with respect to the genuine Major Inscriptions on pillars is that the latter are concerned almost exclusively with Devanampriya Priyadarsi's Dharma, but do not mention either the Sramanas ''Buddhists' or the Brahmanas 'Brahmanists' by name. This is strikingly unlike the Major Inscriptions on rocks, which mention them repeatedly in many of the edicts. In other words, though the Pillar Edicts are all dated later than the Rock Edicts, for some reason (perhaps their brevity), Devanampriya Priyadarsi does not mention the Sramanas or the Brahmanas in them. The "Seventh Pillar Edict" is thus unique in that it does mention the Buddhists (Sramanas) and Brahmanists (Brahmanas) by name, but the reoccurrence of the names in what claims to be the last of Devanampriya Priyadarsi's edicts suggests that the text is not just spurious, it is probably a deliberate forgery. This conclusion is further supported by the above-noted unique passage in the inscription in which the Buddhists are referred to as the "Samgha". This term occurs in the later Buddhist Inscriptions too; but it is problematic because it is otherwise unknown before well into the Saka-Kushan period.79

The one really significant thing the text does is to add the claim that Devanampriya Priyadarsi supported not only the Buddhists and the Brahmanists but also the Ajivikas and Jains. However, all of the Jain holy texts are uncontestedly very late (long after the Mauryan period). The very mention of the sect in the same breath as the others is alone sufficient to cast severe doubt on the text's authenticity.80 The "Seventh Pillar Edict" claims that it was inscribed when Devanampriya Priyadarsi had been enthroned for twenty-seven years; that is, only one year after the preceding text (the sixth of the synoptic Pillar Edicts), which says it was inscribed when Devanampriya Priyadarsi had been enthroned for twenty-six years. The "Seventh Pillar Edict" text consists of passages taken from many of the Major Inscriptions, both Rock and Pillar Edicts, in which the points mentioned are typically dated to one or another year after the ruler's coronation, but in the "Seventh Pillar Edict" the events are effectively dated to the same year. Most puzzling of all, why would the king add such an evidently important edict to only a single one of the otherwise completely synoptic pillar inscriptions?81

Perhaps even more damning is the fact that in the text itself the very same passages are often repeated verbatim, sometimes (as near the beginning) immediately after they have just been stated, like mechanical dittoisms. Repetition is a known feature of Indian literary texts, but the way it occurs in the "Seventh Pillar Edict" is not attested in the authentic Major Inscriptions. Moreover, as Olivelle has noted, the text repeats the standard opening formula or "introductory refrain" many times; that is, "King Priyadarsin, Beloved of the Gods, says"82 is repeated verbatim nine times, with an additional shorter tenth repetition. "In all of the other edicts this refrain occurs only once and at the beginning. Such repetitions of the refrain which state that these are the words of the king are found in Persian inscriptions. However, this is quite unusual for Asoka."83

In fact, this arrangement betrays the actual author's misunderstanding of the division of the authentic Major Inscriptions into "Edicts", and his or her consequent false imitation of them using repetitions of the Edict -- initial formula throughout the text in an attempt to duplicate the appearance of the authentic full, multi-"Edict" inscriptions on rocks and pillars. In short, based on its arrangement, palaeography, style, and contents, the "Seventh Pillar Edict" cannot be accepted as a genuine inscription of Devanampriya Priyadarsi. The text was added to the pillar much later than it claims and is an obvious forgery from a later historical period. These factors require that the "Seventh Pillar Edict" be removed from the corpus of authentic inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarsi....

Bronkhorst (1986) convincingly shows that Brahmanist belief in good and bad karma, and in rebirth, was adopted from early Normative Buddhism, not Early Buddhism. However, belief in an eternal soul was introduced to India by Zoroastrianism, and it is attested as a Brahmanist belief already by Megasthenes, as is belief in one creator God, so it would seem likely that these and some of the other ultimately Zoroastrian beliefs in Brahmanism were adopted directly from that religion, rather than from Buddhism, where at least belief in God (per se) seems never to have been accepted.

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith

We know very little, unfortunately, about these early Brahmanical authors of ascetic texts.20 [There were also parallel codes dealing with forest hermits. Baudhayana (fourth century B.C.E.), for example, explicitly refers to a vaikhanasasastra ("Treatise for Hermits" or "Treatise by Vikhanas"): BDh 2.11.14.] It is not even clear whether their composition and transmission were carried out within or outside the Vedic schools. There is considerable evidence, especially in the epics, nevertheless, for a close association between the early Samkhya school of philosophy and the renunciatory mode of life. Ancient Samkhya teachers, such as Kapila and Pancasikha,21 [Some scholars have identified Pancasikha with Panini's Parasarya on the basis of a reference in the Mahabharata (12.308.24) to Pancasikha as belonging to the lineage of Parasarya (parasaryagotra). See Shastri, 55.] are portrayed as wandering mendicants. Although I am inclined to believe that the earliest Brahmanical literature on renunciation originated among such Samkhya renouncers, there is insufficient evidence at present to demonstrate that conclusion with any certainty, especially because none of these early ascetic texts has been preserved.

One possible reason for the disappearance of independent texts on asceticism may have been the absence of organized ascetic or monastic institutions within Brahmanism until the early medieval period, institutions that would have facilitated the preservation and the transmission of the ancient texts. Another and possibly more important reason may have been the Brahmanical theology of scriptural authority.

By the last few centuries before the common era, Brahmanical theologians had developed the principle that scriptural authority resided solely and primarily in the Veda and derivatively in texts referred to as smrtis. Both these categories of sacred texts, but especially smrti, were very elastic and without recognized canons or boundaries. "Smrti" itself included many categories of texts, themselves without definite boundaries: ritual texts (Srauta- and Grhya-sutras), epics, Puranas, and the like. As time went on, more and more texts, and classes of texts, especially of sectarian provenance, were added to this category. What all the smrti texts have in common, however, is that they are viewed as representing the Vedic tradition, which is the context for transmitting and understanding the Vedas. According to Brahmanical theology, smrtis derive their authority from the Vedas on which they are based. For regulating social conduct and individual morality, the central smrti texts were the Dharma-sutras and their later counterparts, the Dharma-sastras, that are often and significantly referred to simply as smrtis. They are smrti par excellence.

Lacking an independent scriptural tradition, such as those created in Buddhism and Jainism, the only way ascetic codes could acquire scriptural authority within Brahmanism was by being incorporated into the elastic categories of Veda or smrti. The Samnyasa Upanisads are examples of ascetic texts that were either incorporated into or deliberately composed to fit the Vedic category of "Upanisad."

The dharma literature represented by the smrtis,22 [Under this rubric I include not only the ancient Dharma-sastras and the later Dharma-sastras, but also the dharma portions of the epics and Puranas.] however, contains the bulk of the ancient Brahmanical literature on asceticism. There are four extant Dharma-sutras ascribed to Gautama, Baudhayana, Apastamba, and Vasistha and belonging roughly to the last four or five centuries before the common era. Each of them has a section containing the rules of conduct of both renouncers and forest hermits. These are given within the context of the asrama system that permits a person to live a religious life as a student, a householder, a hermit, or a renouncer.23 [ GDh 3.1-36; BDh 2.11.6-34; 2.17-18; ApDh 2.21.1-17; VDh 10.1-31. For further discussion, see 2.6.] It appears likely that these rules were taken from ascetic codes; the Dharma-sutras frequently quote from unnamed sources.24 [See, for example, GDh 3.1; BDh 2.11.8; 2.17.30; 2.18.13; VDh 10.2, 20.] Gautama and Baudhayana, moreover, present the asrama system as the view of an opponent. These rules on asceticism are in prose and set in the aphoristic genre of sutra; in this they do not differ from the other sections of the Dharma-sutras. With the exception of the earliest strata within the Samnyasa Upanisads, the ascetic rules contained in the Dharma-sutras are the earliest extant ascetic literature within the Brahmanical tradition.

The Dharma-sastras, belonging roughly to the first five or six centuries of the common era,...

Gautama Dharmasūtra is a Sanskrit text and likely one of the oldest Hindu Dharmasutras (600-200 BCE), whose manuscripts have survived into the modern age. (Dharma-sutras later expanded into Dharma-shastras) ...

-- Gautama Dharmasutra, by Wikipedia

... as well as the sections dealing with dharma in the epics and the Puranas, follow the sutras in incorporating rules of ascetic behavior within the context of the asrama system.25 [ MDh 6.33-86; YDh 3.56-66; ViDh 96; VaiDh 1.9; 2.6-8; 3.6-8. The Mahabharata and the Puranas also contain discussions of ascetic life, mostly within the context of the asrama system. Several of these passages, such as the dialogue between Bhrgu and Bharadvaja (MBh 12.184), appear to be remnants of extinct Dharma-sutras.] These texts, however, are written for the most part in verse, and versification also characterizes the ascetic literature of this period. Most of these texts are now extinct. There is a staggering number of citations in medieval ascetic texts from these lost Dharma-sastras [dharmasutras?].

When D. P. Walker wrote about "ancient theology" or prisca theologia, he firmly linked it to Christianity and Platonism (Walker 1972). On the first page of his book, Walker defined the term as follows:By the term "Ancient Theology" I mean a certain tradition of Christian apologetic theology which rests on misdated texts. Many of the early Fathers, in particular Lactantius, Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius, in their apologetic works directed against pagan philosophers, made use of supposedly very ancient texts: Hermetica, Orphica, Sibylline Prophecies, Pythagorean Carmina Aurea, etc., most of which in fact date from the first four centuries of our era. [100-400 A.D.] These texts, written by the Ancient Theologians Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Pythagoras, were shown to contain vestiges of the true religion: monotheism, the Trinity, the creation of the world out of nothing through the Word, and so forth. It was from these that Plato [428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC)] took the religious truths to be found in his writings. [LC: How did Plato (428-348 BC) get access across time and space to misdated texts from the 1st-4th centuries A.D.?] (Walker 1972:1)

-- The Ancient Theology: Studies in Christian Platonism from the Fifteenth to the Eighteen Century, by Daniel Pickering Walker (1914-1985)

We have to wait until the medieval period, after the organization of Brahmanical monastic orders, traditionally ascribed to the Advaita theologian Sankara, for the composition of independent ascetic texts. They were probably composed within monastic establishments as handbooks for the use of monks and generally fall within the category of dharma literature known as paddhati, handbooks dealing with specific topics mostly of a ritual nature.26 [The paddhati itself can be viewed as a subcategory of the mbandha class of literature. Nibandhas are not smrti and therefore not part of scripture. They are medieval digests of law in the broadest sense of the term and include all the topics covered in the Dharmasustras.] They did not form part of Veda or smrti, and thus their authority did not transcend the boundaries of their sects. This sociological background also explains the sectarian biases they reveal, even though all claim to hand down the Vedic dharma on asceticism and cite profusely from Vedic and smrti sources. Some of them are even polemical in nature.27 [For such polemical works, see Olivelle 1986 and 1987.]

Within the Brahmanical mainstream, the earliest independent work on renunciation outside the Samnyasa Upanisads that has come down to us is a work called Yatidharmasamuccaya, written by Yadava Prakasa (eleventh century C.E.).28 [See above 1.2 and n. 16. I am currently engaged in preparing a critical edition and translation of this work. Its third chapter is included in Olivelle 1987.] Yadava, according to tradition, subscribed to some form of non-dualist Vedanta but was later converted by his own pupil, Ramanuja; the Sri-Vaisnava tradition claims him as one of its own. He is cited by later Sri-Vaisnava authors, and Vedanta Desika says that only Yadava's "treatise on the dharma of renouncers is unanimously accepted by the learned, just as Manu's law book and the like."29 [Yatilingabhedabhangavada of the Satadusani. See Olivelle 1987, 82.] The medieval period saw the proliferation of similar compendia of ascetic rules and customs, although none can match the depth, comprehensiveness, and lucidity of Yadava's work.30 [Kane (HDh I: 989-1158) lists over eighty such works. Many more have come to light since Kane published his work in 1930. Almost all these works exist only in manuscript and, therefore, are unavailable to all but the most assiduous of scholars. Among the ones published are Visvesvara Sarasvati's Yatidharmasamgraha (cf. YDhS) and Vasudevasrama's Yatidharmaprakasa (ed. and trans. Olivelle 1976 and 1977).]

One of the few, and clearly the most important, independent medieval works on renunciation that is not a mere handbook is Vidyaranya's (literary activity 1330—1385 C.E.) Jivanmuktiviveka. Written from an Advaita Vedanta standpoint, it deals with the state of a renouncer who has achieved the liberating knowledge of Brahman and contains a commentary on the Paramahamsa Upanisad.

The Samnyasa Upanisads fall broadly into the pattern of development traced above. The earlier texts are largely written in prose and often exhibit the pithy style of the sutra genre; this is most evident in the Nirvana Upanisad. Some of them probably existed as texts of the sutra tradition before they were classified as Upanisads.31 [For more details of the prehistory of the early Samnyasa Upanisads, see Sprockhoff 1976. Sprockhoff (1987) has drawn special attention to the similarities between the Kathasruti Upanisad and a section of the Manavasrautasutra.] The Asrama Upanisad, for example, has many recensions, some of which are considered as smrtis.32 [For the textual history of this Upanisad and its relation to the Kanvayana or Katyayana-smrti, see Sprockhoff 1976, 120-124.] Some of the later documents within the Samnyasa Upanisads, such as the Naradaparivrajaka Upanisad, on the other hand, show all the characteristics of medieval legal compendia (nibandha). These later Upanisads are collections of passages, some in prose but mostly in verse, from older smrtis and other sources. Unlike the nibandhas, however, they do not reveal their sources. It appears likely that these later documents were composed deliberately in a manner that would allow them to be perceived as Upanisads.

The fact that the major monasteries of early medieval India—monasteries where the old ascetic texts were preserved and new ones produced—belonged to the Advaita Vedanta tradition may explain the strong Advaita leaning of most of the Samnyasa Upanisads. Old texts with different views may not have been preserved; others may have been recast in the Advaita mold. The only Upanisad of our collection with a non-Advaita, or even an anti-Advaita, orientation is the Satyayaniya, and it was undoubtedly composed within the Sri-Vaisnava camp, possibly to counter the Advaita bias of the others.