by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/15/21

Gautama Maharishi

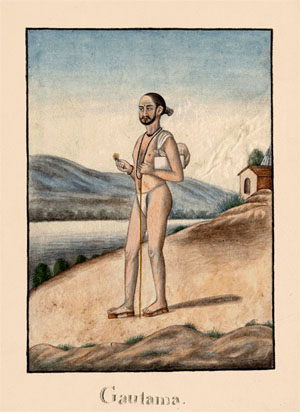

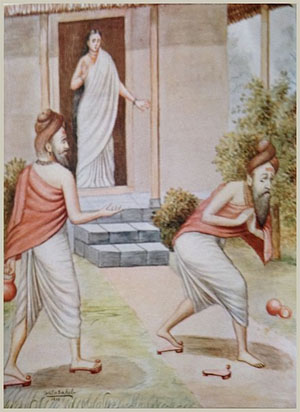

An Early 19th Century Painting Showing Maharishi Gautama

Personal

Religion: Hinduism

Spouse: Ahalya

Children: Shatananda and others

Parents: Gotama (father)

Honors: One of the Saptarishis (Seven Great Sages Rishi)

Gautama Maharishi (Sanskrit: महर्षिः गौतम Mahariṣiḥ Gautama), also known as Vamadeva Gautama[1] was a Rigvedic sage in Hinduism, who is also mentioned in Jainism and Buddhism. Gautama is prominently mentioned in the Ramayana and is known for cursing his wife Ahalya, after she had an relationship with Indra. Another important story related to Gautama is about the creation of river Godavari, which is also known as Gautami.

History

Vamadeva Gautama was the founder of the Vamadeva family. Most of the hymns in Mandala IV of the Rigveda are attributed to him.[1] He was the son of Gotama.[2]

[W]e Gotamas with hymns extol thee, O Agni, as the guardian Lord of riches,

Decking thee like a horse, the swift prizewinner. May he, enriched with prayer, come soon and early...

Thus to thee, Indra, yoker of Bay Coursers, the Gotamas have brought their prayers to please thee...

O mighty Indra, Gotama's son Nodhas hath fashioned this new prayer to thee Eternal,

Sure leader, yoker of the Tawny Coursers. May he, enriched with prayer, come soon and early...

Prayers have been made by Gotamas, O Indra, addressed to thee, with laud for thy Bay Horses...

Thus Agni Jātavedas, true to Order, hath by the priestly Gotamas been lauded.

May he augment in them splendour and vigour: observant, as he lists, he gathers increase...

O JĀTAVEDAS, keen and swift, we Gotamas with sacred song exalt thee for thy glories' sake.

Thee, as thou art, desiring wealth Gotama worships with his song:

We laud thee for thy glories' sake...

O Gotama, desiring bliss present thy songs composed with care

To Agni of the pointed flames...

They drave the cloud transverse directed hitherward, and poured the fountain forth for thirsting Gotama.

Shining with varied light they come to him with help: they with their might fulfilled the longing of the sage...

The Gotamas making their prayer with singing have pushed the well's lid up to drink the water.

No hymn way ever known like this aforetime which Gotama sang forth for you, O Maruts,

What time upon your golden wheels he saw you, wild boars rushing about with tusks of iron.

To you this freshening draught of Soma rusheth, O Maruts, like the voice of one who prayeth.

It rusheth freely from our hands as these libations wont to flow...

The Gotamas have praised Heaven's radiant Daughter, the leader of the charm of pleasant voices.

Dawn, thou conferrest on us strength with offspring and men, conspicuous with kine and horses...

Ye lifted up the well, O ye Nāsatyas, and set the base on high to open downward.

Streams flowed for folk of Gotama who thirsted, like rain to bring forth thousandfold abundance...

Gotama, Purumīlha, Atri bringing oblations all invoke you for protection.

Like one who goes straight to the point directed, ye Nāsatyas, to mine invocation...

Through words and kinship I destroy the mighty: this power I have from Gotama my father.

Mark thou this speech of ours, O thou Most Youthful, Friend of the House, exceeding wise, Invoker...

The Gotamas have sung their song of praise to thee that thou mayst give,

Indra, for lively energy.

We will declare thy hero deeds, what Dāsa forts thou brakest down,

Attacking them in rapturous joy.

The sages sing those manly deeds which, Indra, Lover of the Song,

Thou wroughtest when the Soma flowed.

Indra, the Gotamas who bring thee praises have grown strong by thee.

Give them renown with hero sons...

A Warrior thou by strength, wisdom, and wondrous deed, in might excellest all that is.

Hither may this our hymn attract thee to our help, the hymn which Gotamas have made...

-- The Rig Veda, translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith

Children

According to Valmiki Ramayan, Gautama's eldest son with Ahalya is Satananda. But according to Adi Parva of Mahabharata, he had two sons named Saradvan and Cirakari. Saradvan was also known as Gautama, hence his children Kripa and Kripi were called Gautama and Gautami respectively. A daughter of Gautama is referred too but her name is never disclosed in the epic.[3] In Sabha Parva, he begets many children upon Aushinara (daughter of Ushinara), amongst whom eldest in Kakshivat. Gautama and Aushinara's marriage takes place at Magadha, the kingdom of Jarasandha.[4] According to Vamana Purana, he had three daughters named Jaya, Jayanti and Aparajita.[5]

Ahalya's curse

Gautama (left) discovers Indra disguised as Gautama fleeing, as Ahalya watches.

The Ramayana describes Ahalya as his wife. Their marriage is recorded in the Uttara Kanda, which is believed as an interpolation to the epic. As per the story Brahma, the creator god, creates a beautiful girl and gifts her as a bride to Gautama and a son named Shatananda is born. The Bala Kanda mentions that Gautama spots Indra, who is still in disguise, and curses him to lose his testicles. Gautama then returns to his ashram and accepts her.

References

1. Jamison, Stephanie; Brereton, Joel P. (2014). The Rigveda - the earliest religious poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 556.

2. Jamison and Brereton 2014, p. 563-564.

3. "Puranic encyclopaedia: a dictionary with special reference to the epic and Puranic literature". archive.org. 1975.

4. Mahabharata Sabha Parva Section XXI

5. "Puranic encyclopaedia : a dictionary with special reference to epic and Puranic literature". archive.org. 1975.

• Doniger, Wendy (1999). "Indra and Ahalya, Zeus and Alcmena". Splitting the Difference: Gender and Myth in Ancient Greece and India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15641-5.

*********************

Gautama Dharmasutra

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/17/21

I have a larger vision or fantasy of original Indian Buddhism as an ocean with many icebergs, each representing the local textual traditions...of the different parts of the Indian world. Those icebergs are mostly gone...We have the Pali canon...the partial Sanskrit canon...They had a common core but they had many different texts in and around that basic commonality... and... there's no hope of finding them mainly for a simple physical reason, the climate of...India proper is such that organic materials...never last for more than a few hundred years. There are really no really old manuscripts in India proper. You only get the ancient manuscripts from the borderlands of India, in this case Gandhara which has a more moderate climate.

-- One Buddha, 15 Buddhas, 1,000 Buddhas, by Richard Salomon

Gautama Dharmasūtra is a Sanskrit text and likely one of the oldest Hindu Dharmasutras (600-200 BCE), whose manuscripts have survived into the modern age.[1][2][3]

The Gautama Dharmasutra was composed and survives as an independent treatise,[4] unattached to a complete Kalpa-sūtras, but like all Dharmasutras it may have been part of one whose Shrauta- and Grihya-sutras have been lost to history.[1][5] The text belongs to Samaveda schools, and its 26th chapter on penance theory is borrowed almost completely from Samavidhana Brahmana layer of text in the Samaveda.[1][5]

The Samaveda (Sanskrit: सामवेद, sāmaveda, from sāman "song" and veda "knowledge"), is the Veda of melodies and chants. It is an ancient Vedic Sanskrit text, and part of the scriptures of Hinduism. One of the four Vedas, it is a liturgical text which consists of 1,549 verses. All but 75 verses have been taken from the Rigveda. Three recensions of the Samaveda have survived, and variant manuscripts of the Veda have been found in various parts of India.

While its earliest parts are believed to date from as early as the Rigvedic period, the existing compilation dates from the post-Rigvedic Mantra period of Vedic Sanskrit, between c. 1200 and 1000 BCE or "slightly rather later," roughly contemporary with the Atharvaveda and the Yajurveda.

Embedded inside the Samaveda is the widely studied Chandogya Upanishad and Kena Upanishad, considered as primary Upanishads and as influential on the six schools of Hindu philosophy, particularly the Vedanta school. Samaveda has the root of music and dance tradition of this planet.

It is also referred to as Sama Veda....

R. T. H. Griffith says that there are three recensions of the text of the Samaveda Samhita:

• the Kauthuma recension is current in Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, West Bengal and since a few decades in Darbhanga, Bihar,

• the Rāṇāyanīya in the Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gokarna, few parts of Odisha, Andhra Pradesh

• and the Jaiminiya in the Carnatic, Tamil Nadu and Kerala...

Just like Rigveda, the early sections of Samaveda typically begin with Agni and Indra hymns but shift to abstract speculations and philosophy, and their meters too shifts in a descending order. The later sections of the Samaveda, states Witzel, have least deviation from substance of hymns they derive from Rigveda into songs. The purpose of Samaveda was liturgical, and they were the repertoire of the udgātṛ or "singer" priests...

The Samaveda consists of 1,549 unique verses, taken almost entirely from Rigveda, except for 75 verses. The largest number of verse come from Books 9 and 8 of the Rig Veda. Some of the Rigvedic verses are repeated more than once. Including these repetitions, there are a total of 1,875 verses numbered in the Samaveda recension translated by Griffith.

Samaveda samhita is not meant to be read as a text, it is like a musical score sheet that must be heard...

The Kauthuma recension has been published (Samhita, Brahmana, Shrautasutra and ancillary Sutras, mainly by B.R. Sharma), parts of the Jaiminiya tradition remain unpublished. There is an edition of the first part of the Samhita by W. Caland and of the Brahmana by Raghu Vira and Lokesh Chandra, as well as the neglected Upanishad, but only parts of the Shrautasutra. The song books remain unpublished.

A German edition of Samaveda was published in 1848 by Theodor Benfey, and Satyavrata Samashrami published an edited Sanskrit version in 1873. A Russian translation was published by Filipp Fortunatov in 1875. An English translation was published by Ralph Griffith in 1893. A translation in Hindi by Mridul Kirti called "Samveda Ka Hindi Padyanuvad" has also been published recently.

The Samaveda text has not received as much attention as the Rigveda, because outside of the musical novelty and melodic creativity, the substance of all but 75 verses of the text have predominantly been derived from the Rigveda. A study of Rigveda suffices.

-- Samaveda, by Wikipedia

The text is notable that it mentions many older texts and authorities on Dharma, which has led scholars to conclude that there existed a rich genre of Dharmasutras text in ancient India before this text was composed.[6][7]

Authorship and dates

Testimony during a trial

The witness must take an oath before deposing.

Single witness normally does not suffice.

As many as three witnesses are required.

False evidence must face sanctions.

— Gautama Dharmasutras 13.2-13.6 [8][9]

The Dharmasutra is attributed to Gautama, a Brahmin family name, many of whose members founded the various Shakhas (Vedic schools) of Samaveda.[1] The text was likely composed in the Ranayaniya branch of Samaveda tradition, generally corresponding to where modern Maratha people reside (Maharashtra-Gujarat).[1] The text is likely ascribed to revered sage Gautama of a remote era, but authored by members of this Samaveda school as an independent treatise.[10]

Kane estimated that Gautama Dharmasastra dates from approximately 600-400 BCE.[11] However, Olivelle states that this text discusses the progeny of Greeks with the word Yavana, whose arrival and stay in substantial numbers in northwest India is dated after Darius I (~500 BCE). The Yavana are called border people in the Edict of Ashoka (256 BCE), states Olivelle, and given Gautama gives them importance as if they are non-border people, this text is more likely to have been composed after the Ashoka's Edict, that is after mid 3rd century BCE.[12] Olivelle states that the Apastamba Dharmasutra is more likely the oldest extant text in Dharmasutras genre, followed by Gautama Dharmasastra.[2] Robert Lingat, however, states that the mention of Yavana in the text is isolated, and this minor usage could well have referred to Greco-Bactrian kingdoms whose border reached into northwest Indian subcontinent well before the Ashoka era. Lingat maintains that the Gautama Dharmasastra may well pre-date 400 BCE, and he and other scholars consider it to be the oldest extant Dharmasutra.[13][3]

Regardless of the relative chronology, the ancient Gautama Dharmasutra, states Olivelle, shows clear signs of a maturing legal procedure tradition and the parallels between the two texts suggest that significant Dharma literature existed before these texts were composed in 1st millennium BCE.[14][15][7]

The foundational roots of the text may pre-date Buddhism because it reveres the Vedas and uses terms such as Bhikshu for monks, which later became associated with Buddhists, and instead of Yati or Sannyasi terms that became associated with Hindus.[13] There is evidence that some passages, such as those related to castes and mixed marriages, were likely interpolated into this text and altered at the later date.[16]

Organization and content

The text is composed entirely in prose, in contrast to other surviving Dharmasutras which contain some verses as well.[13] The content is organized in the aphoristic sutra style, characteristic of ancient India's sutra period.[17] The text is divided into 28 Adhyayas (chapters),[13] with cumulative total of 973 verses.[18] Among the surviving ancient texts of its genre, the Gautama Dharmasutra has the largest portion (16%) of sutras dedicated to government and judicial procedures, compared to Apastamba's 6%, Baudhayana's 3% and Vasishtha's 9%.[19]

The contents of the Gautama Dharmasutra, states Daniel Ingalls, suggest that private property rights existed in ancient India, that the king had a right to collect taxes and had a duty to protect the citizens of his kingdom as well as settle disputes between them by a due process if and when these disputes emerged.[20]

The topics of this Dharmasūtra are arranged methodically, and resembles the structure of texts found in much later Dharma-related smṛtis (traditional texts).[5]

Gautama Dharmasutras

Chapter / Topics (incomplete) / Translation Comments

1. Sources of Dharma

1.1-4 / Origins and reliable sources of law / [21]

2. Brahmacharya

1.5-1.61 / Student's code of conduct, insignia, rules of study / [22]

2.1-2.51 / General rules, conduct towards teachers, food, graduation / [23]

3. Stages of life

3.1-3.36 / Student, monk, anchorite / [24]

4.1-8.25 / Household, marriage, rituals, gifts, respect for guests, behavior during times of crisis and adversity, interaction between Brahmins and the king, ethics and virtues / [25][26][27]

9.1-9.74 / Graduates / [28]

10.1-10.66 / Four social classes, their occupations, rules of violence during war, tax rates, proper tax spending, property rights / [29][30]

4. Judiciary

11.1-11.32 / The king and his duties, judicial process / [31]

12.1-13.31 / Criminal and civil law categories, contract and debts, theory of punishment, rules of trial, witnesses / [32][26]

5. Personal rituals

14.1-14.46 / Death in a family, cremation, impurities and purification after handling corpses / [33]

15.1-15.29 / Rites of passage for ancestors and the death of loved ones / [34]

16.1-16.49 / Self-study of texts, recitation, annual suspension of Vedic readings / [35]

17.1-17.38 / Food, health, prohibition on killing or harming animals to produce food / [36]

18.1-18.23 / Marriage, remarriage, child custody disputes / [37]

6. Punishment and penances

18.24-21.22 / Seizure of property, excommunication, expulsion, readmission, sins / [38]

22.1-23.34 / Penances for killings animals, adultery, illicit sex, eating meat, different types of penances / [39]

7. Inheritance and conflicts within law

28.1-28.47 / Inheritance rights of sons and daughters on man's property, on woman's property, levirate, estates, partition of property between relatives / [40]

28.48-28.53 / Resolving disputes and doubts within law / [41]

Commentaries

Duties of a graduate

He should not spend the morning, midday or afternoon fruitlessly,

but pursue righteousness, wealth and pleasure,

to the best of his ability,

but among them he should attend chiefly to righteousness.

— Gautama Dharmasutra 9.46-9.47[42]

Maskarin and Haradatta both commented on Gautama Dharmasūtra – the oldest is by Maskarin in 900-1000 CE, before Haradatta (who also commented on Apastamba).[43]

Olivelle states that Haradatta while writing his commentary on Gautama Dharmasutra titled Mitaksara[44] copied freely from Maskarin's commentary.[43] In contrast, Banerji states that Haradatta's commentary is older than Maskarin's.[45] Asahaya may have also written a commentary on the Gautama text, but this manuscript is either lost or yet to be discovered.[45]

Influence

Daniel Ingalls, a professor of Sanskrit at the Harvard University, states that the regulations in the Gautama Dharmasutra were not laws for the entire society, but were regulations and code of conduct that were developed and applied "strictly to one small group of Brahmins".[46] The Gautama text was part of the curriculum of one of the Samaveda schools, and most of the rules, if enforceable, states Ingall, applied to just this group.[46]

It is quite likely, states Patrick Olivelle, that the ideas and concepts in the Gautama Dharmasutra strongly influenced the authors of the Manusmriti.[19][47] Medieval texts, such as Apararka, state that thirty six Dharmasastra authors were influenced by Gautama Dharmasutras.[48]

See also

• Arthashastra

• Manusmriti

• Upanishads

• Vedas

References

1. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 19.

2. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 178 with note 28.

3. Daniel H.H. Ingalls 2013, p. 89.

4. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 186.

5. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 74.

6. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 19-20.

7. Timothy Lubin, Donald R. Davis Jr & Jayanth K. Krishnan 2010, p. 38.

8. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 69.

9. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 100-101.

10. Timothy Lubin, Donald R. Davis Jr & Jayanth K. Krishnan 2010, p. 40.

11. Patrick Olivelle 1999, p. xxxii.

12. Patrick Olivelle 1999, p. xxxiii.

13. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 20.

14. Patrick Olivelle 2005, p. 44.

15. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 19-22, Quote: The dharma-sutra of Apastamba suggests that a rich literature on dharma already existed. He cites ten authors by name. (...)..

16. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 19-20, 94.

17. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 178.

18. Patrick Olivelle 2005, p. 46.

19. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 186-187.

20. Daniel H.H. Ingalls 2013, p. 91-93.

21. Patrick Olivelle 1999, p. 78.

22. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 78-80.

23. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 80-83.

24. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 83-84.

25. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 84-91.

26. Daniel H.H. Ingalls 2013, pp. 89-90.

27. Kedar Nath Tiwari (1998). Classical Indian Ethical Thought. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-81-208-1607-7.

28. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 91-93.

29. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 94-96.

30. Penna, L. R. (1989). "Written and customary provisions relating to the conduct of hostilities and treatment of victims of armed conflicts in ancient India". International Review of the Red Cross. Cambridge University Press. 29 (271): 333–348. doi:10.1017/s0020860400074519.

31. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 96- 98.

32. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 98-101.

33. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 101-103.

34. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 103-106.

35. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 107-108.

36. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 108-109.

37. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 110-111.

38. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 111-115.

39. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 115-118.

40. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 118-126.

41. Patrick Olivelle 1999, p. 126.

42. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 92-93.

43. Patrick Olivelle 1999, p. 74.

44. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 114.

45. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. pp. 72–75. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

46. Daniel H.H. Ingalls 2013, p. 90-91.

47. Patrick Olivelle 2005, pp. 44-45.

48. Timothy Lubin, Donald R. Davis Jr & Jayanth K. Krishnan 2010, p. 51.

Bibliography

• Daniel H.H. Ingalls (2013). Roy W. Perrett (ed.). Theory of Value: Indian Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-70357-8.

• Timothy Lubin; Donald R. Davis Jr; Jayanth K. Krishnan (2010). Hinduism and Law: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49358-1.

• Patrick Olivelle (1999). Dharmasutras: The Law Codes of Ancient India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7.

• Patrick Olivelle (2005). Manu's Code of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4.

• Patrick Olivelle (2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

• Robert Lingat (1973). The Classical Law of India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01898-3.