Tibet's Cold War: The CIA and the Chushi Gangdrug Resistance, 1956-1974

by Carole McGranahan

University of Colorado Boulder

Article in Journal of Cold War Studies

Vol. 8, No. 3, Summer 2006, pp. 102–130

July 2006

© 2006 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Introduction

Colorado’s mountain roads can be treacherous in the winter, and in December 1961 a bus crashed on an icy road in the middle of the night.1 The crash delayed the bus’s journey, and morning had already broken by the time the bus pulled into its destination, Peterson Airfield in Colorado Springs. The coffee had just begun to brew when airfield workers discovered that they were surrounded by heavily-armed U.S. soldiers. The troops ordered them into two different hangars and then shut and locked the doors. Peeking out the windows of the hangars, the airfield employees saw a bus with blackened windows pull up to a waiting Air Force plane. Fifteen men in green fatigues got out of the bus and onto the plane. After the aircraft took off, an Army officer informed the airfield employees that it was a federal offense to talk about what they had just witnessed. He swore them to the highest secrecy, but it was already too late: The hangars in which the scared civilians had been locked were equipped with telephones, and they had made several calls to local newspapers. The next day the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph ran a brief story quoting a student pilot who said that “several Oriental soldiers in combat uniforms” were involved. The short story caught the attention of a New York Times reporter in Washington, DC, who called the Pentagon for more information. His call was returned by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who killed the story not only by uttering the words “top secret national security,” but also by confiding to the reporter that the men were Tibetans.

A Tibetan proverb states that “an unspoken word has freedom, a spoken word has none.” But the freedom of things unspoken is not without limits. Secrets, for example, though supposedly not to be told, derive their value in part by being shared rather than being kept. Sharing secrets—revealing the unspoken—often involves cultural systems of regulation regarding who can be told, who they in turn can tell, what degree of disclosure is allowed, and so on. As a form of control over knowledge, secrecy is recognized in many societies as a means through which power is both gained and maintained.2 Together, Tibet and the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) present the irresistible combination of two twentieth-century icons of forbidden mystery and intrigue—Tibet, Shangri-La, the supposed land of mystical and ancient wisdom; and the CIA, home of covert activities, where even the secrets have secrets.

The Tibetans in Colorado were members of a guerrilla resistance force that fought against the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) from 1956 through 1974. Begun as a series of independent uprisings against increasingly oppressive Chinese rule, the resistance soon grew into a unified volunteer army, known as the Chushi Gangdrug Army. The Chushi Gangdrug Army fought against the PLA first from within Tibet and later from a military base in Mustang, a small Tibetan kingdom within the borders of Nepal. For much of this time, the resistance was covertly trained and financially supported by the U.S. government, specifically the CIA. Stories of this guerrilla war were secret for many years. Because the operation encompassed multiple governments and the clandestine transfer of men, money, and munitions across international borders, it is perhaps no surprise that information about the resistance, and more specifically about U.S.-Tibetan relations, was suppressed until recently. Secrets of the Tibetan resistance, however, are not always as they appear. They are not only political but also ethnographic, built on cultural systems of meaning and action.

In this article, I contend that our understanding of the Tibetan resistance must include attention to cultural as well as historical and political formations. Our analysis of the Tibetan resistance must not remain just a historical or political project or a story viewed solely through a Cold War lens. Instead, ethnographic detail and explanation, and the nuances of culture and community, must be included if we are to achieve the fullest possible understanding of the transnational and continuing saga that is the Tibetan resistance. An ethnographic approach is useful because the resistance is not one that was crafted solely, or even predominantly, in offices in Washington, DC. Instead, the resistance was forged through conversation, debate, and action among its own members and leaders at least as much as it was organized in dialogue with U.S. officials. Anthropology relies on a similar methodology—participant observation, in which the researcher engages in face-to-face and everyday interaction with research subjects over an extended period of time (often years) within host communities. My exploration of contemporary perspectives on the Tibetan resistance is through a tripartite analysis—one that is historical, political, and anthropological. In addition, my inquiry is not situated solely at the level of the state or government; it is focused instead on the resistance movement itself and the individuals who constituted it.

The article is based on primary and secondary sources generated mainly from within the Tibetan refugee community. Over a five-year period from 1994 to 1999, I collected oral histories of the resistance from leaders of the resistance as well as regular soldiers. In addition, I have examined a number of Tibetan-language books and articles about the resistance published from the late 1950s to the present, many of which contain information and insights not yet appreciated by outside observers.3 Finally, I have consulted the small but growing secondary literature on the resistance in English, including some of the thousands of hits that turn up in an Internet search for the “Tibetan resistance.”

The case of Tibet presents a mostly unexplored example of covert Cold War military intervention. By the mid-1950s the Tibetan Chushi Gangdrug army had already defined the PLA as a threat to Tibetan national security, but the intervention of the U.S. government provided external confirmation of the threat that China posed to Tibet. The covert nature of U.S. military assistance to the Tibetans, however, meant that this external validation was not presented to the world. Unlike the Korean War, in which Jennifer Milliken argues that outside intervention constituted “a particularly significant moment in the broader process of (re)constituting the Western security collectivity,”5 Tibetan resistance to the Chinese remained mostly insignificant for much of the Western world. Resolutions on Tibet at the United Nations (UN) were introduced by weak, peripheral states—Ireland and Malaya in 1959, and Malaya and Thailand with the support of El Salvador and Ireland in 1961— albeit often with the encouragement of U.S. diplomats. For the most part, the United States, even while supporting the Tibetan resistance (and exile government), framed the Tibet-China conflict in international forums such as the UN in the language of human rights rather than of state sovereignty. Among the many results of this policy is a degree of ambiguity regarding where the Tibet-China conflicts fits in terms of academic discourse as well as political negotiation. Is this conflict purely an “internal issue” as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) would have it, or is it an international issue, one between two states, as the Tibetan government-in-exile sees it? Given that at the time of the PRC’s incorporation of Tibet, Tibet was de facto an independent state,6 and that multiple states were involved in either actively or involuntarily facilitating the Tibetan resistance, it is important to situate discussions of Tibet within an international framework of analysis.

Anthropology and Cold War Studies

Anthropologists are increasingly turning their attention to studies of the Cold War. From the study of U.S. intelligence and military operations, especially among marginalized groups and countries, to the study of weapons complexes and on to the conceptual and disciplinary apparatuses directing our academic labor as well as everyday life and international affairs around the world, anthropologists are approaching Cold War pasts and post–Cold War presents with an analytical energy reminiscent of disciplinary debates during the Vietnam War.7 In anthropological terms, bringing culture into analyses of political and military history provides important vantage points from which to understand the workings of power, especially in cases of international action and intervention.8 In the merging of ethnography and Cold War studies, culture contributes much more than a variable for explaining anomalous phenomena. 9 Instead, culture provides and pervades backdrops, logics, and structures of all parties and institutions involved. Just as an analysis of the Tibetan resistance requires an understanding of the cultural principles that directed systems of authority and action among the guerrillas, so too does culture have a latent yet orchestral presence in the actions of the U.S. government in Asia and elsewhere. As understood by anthropologists, culture is an all-pervasive and ordered system of meaning that is learned and shared by members of a group. Although all cultures are unique and holistic, appearing habitual or normal to their members, contestation and constraint are also important elements of culture. Everyday life, political violence, economic systems, and the state and nation-building projects that characterize the post- 1945 era are all cultural products, in some respects sharing universal features and in other respects maintaining an autonomy built on culture and notions of difference.

Difference has long been a key element of anthropology, specifically in terms of describing and explaining the “otherness” of cultures outside Euro- American norms.10 John Borneman argues that in the United States, anthropology’s focus on global otherness, rather than solely on different communities within the nation, aligns the discipline (intentionally or not) with the conceptual apparatus of foreign policy.11 Early anthropological concepts used in analyses of American Indian communities, for example, helped shape U.S. policy toward these communities. The policies in turn became a template for state strategies vis-à-vis non-European foreigners.12 In highlighting the political applications of native/other anthropological categories, Borneman argues that “through its institutionalized focus on defining the foreign, anthropology may best be thought of as a form of foreign policy.”13

In the case of the Tibetan resistance, the outline of CIA programs and training drew on prior operations, with modifications made while the Tibet program was under way.14 The modifications were usually made or suggested by CIA officers in the field with the Tibetans, rather than those back in Langley. The Tibet operation both did and did not fit into Cold War models; it lasted significantly longer than most CIA operations and was a project built on a lack of anthropological or intelligence information.15 In both its anomalous and its conforming aspects, the Tibet-CIA connection was an important part of the foreign relations of both countries for two decades.

Recently, anthropologists and international relations scholars have begun a sustained discussion of how the theoretical arguments of each field push the other to further clarity or to revision of long-established disciplinary thought. The most provocative example of this joint enterprise is the edited volume Cultures of Insecurity: States, Communities, and the Production of Danger, in which an interdisciplinary team of scholars convincingly show the value of considering culture and the state within the same analytical frame.16 In a foreword to the volume, the anthropologist George Marcus argues forcefully for an ethnographic engagement with the mainstream of international relations, as well as a critique built on the terms of the field itself.17 His proposal is expressly anthropological because, as all beginning anthropology students learn, the goal of ethnography is to combine emic (inside) perspectives with etic (outside) perspectives in our collection and analyses of data. One example of such an ethnographic endeavor is Hugh Gusterson’s study of the Lawrence Livermore nuclear weapons laboratory. Gusterson describes his work as not just providing a constructivist alternative to the mostly positivist nuclear studies, but also as breaking with “the radical separation of the domestic and international levels of analysis that has been a defining feature of dominant thinking in international security studies, especially (neo)realism.”18 Understanding U.S. nuclear weapons projects requires understanding the culture of nuclear weapons laboratories, including the relations of weapons scientists to local institutions, national movements, and international politics.19

The study of CIA involvement in the Tibetan resistance is no different. An assessment of this complicated relationship is predicated on ethnographic understandings of the various groups involved. Rather than looking solely at political costs and strategies, an ethnographic approach begins with an explanation of the cultural factors that drive the operative political calculus within which costs, strategies, and the like are determined. The CIA has been subject to much more rigorous (though not necessarily ethnographic) evaluation than has the Tibetan resistance.20 In this article, therefore, my focus is primarily on the Chushi Gangdrug resistance army as interpreted by three groups—the resistance itself, the Tibetan government-in-exile, and agents of the U.S. government. Although each group presents itself as unified, they actually comprise individuals and factions whose views range from consent to dissent in relation to the group’s center. A closer look at the resistance allows us to see more clearly how the making of the refugee Tibetan community and exile Tibetan state was tied into Cold War politics at global as well as local levels.

The Founding of Chushi Gangdrug

The Tibetan resistance began as a series of independent uprisings in the eastern region of Kham (Khams). In 1949 and 1950, officials of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and PLA took over the administration of villages throughout Kham, and eventually in all of Tibet. This “liberation” of the Tibetans was initially tempered by a policy of relative generosity and tolerance in terms of the changes made in the region. However, as sweeping changes were gradually introduced, the situation deteriorated. Local lay and religious leaders were stripped of power, and much that had previously defined normal life in Kham was disturbed. Khampa villagers from all social backgrounds soon began to rise up in protest. These protests were often coordinated by the families and monastic leaders whose authority the Chinese had attempted to undermine. As conditions worsened in the region, people began to head west toward Lhasa, the Tibetan capital.

Khampa Tibetans entering the Lhasa area set up camps on the outskirts of the city. Leaders of the various districts of Kham met and devised plans to sponsor a long-life ceremony for the Dalai Lama and to present him with a golden throne. Along with this public show of support for the Dalai Lama, the leaders decided to unite their formerly separate citizen-soldiers into a unified volunteer army. The independent armies, which had fought under the name bstan srung dang blangs dmag, or “volunteer troops to defend religion and country,” now took the name chu bzhi gangs drug dmag, the “Four Rivers and Six Ranges Army,” in reference to the “four rivers [and] six ranges” of Kham. On 16 June 1958 the united army known as Chushi Gangdrug held its inaugural ceremony in the Lhoka region south of Lhasa.21

The inaugural included a cavalry parade, a ritual procession of a photograph of the Dalai Lama, and the unveiling of the newly-designed Chushi Gangdrug flag. The flag consisted of two deities’ swords with a religious thunderbolt and lotus flowers on the handles set against a background of yellow, the color of Buddhism.22 The army’s headquarters, along with a secretariat and finance department, were established at Triguthang with a total of roughly 5,000 volunteer soldiers. Four of the volunteers were selected as top commanders, five were chosen as liaison officers between the army and the community, five others were to take care of supplies and equipment, eighteen were designated as field commanders, and a captain was appointed for each group of ten soldiers.23 Altogether, thirty-seven units of varying size, grouped by district of origin and assigned names corresponding to letters of the Tibetan alphabet (e.g., ka, kha, ga, nga), were organized.24 The commanders drew up a code of conduct with twenty-seven rules including prohibitions against stealing, rape, entering houses while on a mission, and harming innocent people. The code also stipulated that soldiers were to protect local people from bandits. This last rule was important because the Chinese authorities had been paying bandits, who roamed throughout Tibet, to pose as Chushi Gangdrug soldiers who would terrorize villages, steal, rape women and nuns, and kill innocent people.25 A merit system was also introduced, including, for example, a cash prize of 500 Indian rupees for the capture of a Chinese army officer’s possessions or documents.26

The founding of Chushi Gangdrug served not just to unify disparate groups in their resistance to the Chinese, but also to institutionalize international resistance activities already under way. Following the signing of the “Seventeen-Point Agreement” between China and Tibet on 17 May 1951, several high-ranking Tibetan officials, including Prime Minister Lhukhang and one of the Dalai Lama’s elder brothers, Gyalo Thondup, decided to travel to India to consult with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Part of the advice Nehru gave them was to encourage a people’s democratic movement that would be recognized by the world as a legitimate alternative to the Chinese. Lhukhang and Gyalo Thondup conveyed this information to Lord Chamberlain Phala, who in turn encouraged such a development in Lhasa. The Mimang Tsogpa (mi mang tshogs pa), or People’s Party, was soon formed under the leadership of Alo Chhonzed, with sixty-two members representing all three provinces of Tibet.27 The leaders of Mimang Tsogpa protested the Dalai Lama’s 1954 trip to China, urging him not to go, and met him in Kham on his return to Lhasa in 1955. Members of the group also distributed pamphlets and put up posters in Lhasa protesting the Chinese presence and calling on Tibetans to unite against the Chinese. Andrug Gompo Tashi, a Mimang Tsogpa officer who would later lead Chushi Gangdrug, later recalled distributing leaflets that “exhorted all Tibetans to unite and protect their freedom and country in an active and not—what was until now—passive posture.” 28

In 1956, as conditions worsened in Kham, including the bombing of four monastic complexes, Mimang Tsogpa began a series of public protests against the Chinese. They delivered a letter of protest directly to the Chinese authorities calling on Chinese forces to leave Tibet.29 The Chinese authorities demanded that the Tibetan government arrest those responsible. The local officials arrested three of the organizers, one of whom later died in jail. In the meantime, many Tibetans, who were secretly meeting in Lhasa and elsewhere to determine what could be done, all arrived at the same conclusion—that outside help was needed. A group of Khampa Tibetan traders met with Gyalo Thondup to ask him to contact foreign countries for military aid, unaware that the Americans had already approached him regarding the situation in Tibet. 30 In the summer of 1956, the Far East Division of the CIA had decided to support the independent Tibetan resistance in their fight against the Chinese. Gyalo Thondup sent the traders back to Lhasa, where they linked up with Andrug Gompo Tashi and began to organize the resistance army.

Chushi Gangdrug’s military inauguration in 1958 angered the Chinese authorities, who began to pressure the Tibetan government to disband the volunteer army. On several occasions the Tibetan government sent emissaries to Chushi Gangdrug headquarters, some of whom ended up joining the resistance. 31 The volunteer army included battalions from the northeast region of Amdo as well as troops from Central Tibet and even several Nationalist Chinese soldiers, but was composed mostly of troops from the eastern region of Kham. Thus, although the resistance army was a pan-Tibetan unit, it was dominated by Khampa Tibetans, a phenomenon never fully appreciated by outsiders.

The Eagle and the Snow Lion

The United States and Tibet do not have a long history of governmental relations. Contact was first made under President Franklin Roosevelt in 1942, shortly after the United States had entered World War II. The U.S. government wanted to transport supplies over and through Tibet to troops in China. Roosevelt sent two undercover Office of Strategic Services envoys to Lhasa to seek approval.32 The mission was successful, but the next interaction between the two countries did not come until 1947–1948 when a Tibetan trade mission, traveling on Tibetan passports, came to the United States as part of a global mission to strengthen Tibet’s international economic and political relations at a time of growing political pressure from China.

With the Communist takeover in China in 1949, U.S. interest in Tibet grew exponentially. Histories of the Tibetan resistance, therefore, are not just Tibetan histories but a part of the broader history of the Cold War. Tibet had an important role in U.S. Cold War strategy in Asia as both a counter to Communist China and a facilitator of U.S. relations with Pakistan and India. 33 Although many Americans who were politically involved with Tibet at this time developed strong personal support for the Tibetans, Tibet remained for the U.S. government, as it had been for the British, a “pawn on the imperial chessboard.”34 The Tibetans themselves, to use the words of a former CIA officer, were thus “orphans of the Cold War.”35

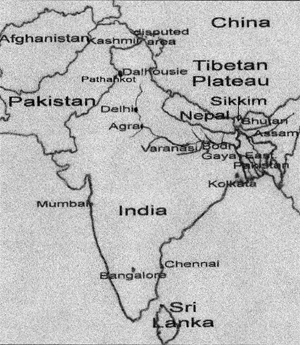

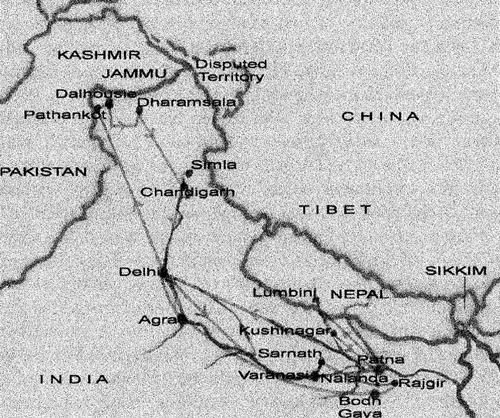

South Asia was never divorced from Cold War politics.36 The departure of the British from India in 1947 led to the partition of the subcontinent and the emergence of the independent states of India and Pakistan. The two countries were quickly embroiled in a contentious dispute with each other and were also pulled into Cold War battles involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and the PRC. Pakistan was first closely linked with the United States and then later on with China. India took a different route, publicly proclaiming a nonaligned status while secretly courting and being courted by Washington, Moscow, and Beijing. The secretive, constantly changing, and often contradictory allegiances among governments in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in several armed conflicts—the Sino-Indian War of 1962, the Indo- Pakistani War of 1965, the ongoing insurgency in Kashmir, and the Tibetan conflict with China.37

It was China that pulled South Asia into the Cold War, often over border disputes involving Tibet. Tibet’s new status as an occupied country and a site of Cold War conflict was a significant departure from its status in the preceding fifty years. During the first half of the twentieth century, Tibet kept a low international profile.38 Its affiliation with China, based on a religious-political relationship, ended when the Qing Dynasty fell. From 1911 on, Tibet was an independent state, uninvolved in any of the world wars but ideologically and religiously supporting the Allies in World War II. In turn, the British and later the Americans encouraged Tibetan political independence, though only to the point where it would not seriously upset China. Despite ideological and other differences between successive Chinese regimes, each was interested in bringing Tibet within the Chinese political orbit.39 Mao Zedong’s China was no different in that respect.

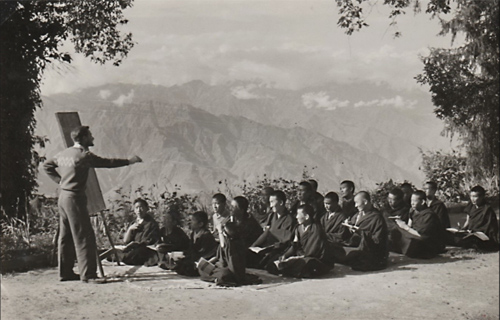

From the start, Mao announced that his intention was to “liberate” Tibet and restore it to the Chinese motherland.40 He was true to his word—Chinese troops entered eastern Tibet in the spring of 1950 and quickly secured control over all of Tibet by occupying Lhasa in the fall of 1950. After an initial period of attempted cooperation with the Chinese, the situation disintegrated rapidly for the Tibetans. In eastern Tibet, people began a series of independent revolts, which the Chinese brutally suppressed using air strikes and ground warfare. The U.S. government had offered aid to the Tibetan government after China invaded, and the Tibetans asked the United States for military aid in 1955. The CIA established its Tibet program the next year. An initial group of six Tibetans were trained on the island of Saipan and then airdropped into Tibet. In the meantime, the previously independent groups of Tibetans who had been fighting the Chinese were brought into the united resistance movement. CIA training of Tibetan soldiers continued in the United States, first at a secret site in Virginia and then, starting in May 1958, at the equally secret Camp Hale in Leadville, Colorado. Over the next six years, several hundred Tibetans were trained at Camp Hale in a variety of guerrilla war- fare techniques such as paramilitary operations, bomb building, map making, photographic surveillance, radio operation techniques, and intelligence collection.

“The [Tibetans] were the best men I worked with,” says Tony Poe, a retired CIA officer who trained the Tibetan soldiers and later worked in Laos. Poe is believed to be the real-life model for the character of Kurtz in Apocalypse Now.41 He and the other American instructors are remembered fondly by the Tibetans themselves. “They were good people” (mi yag po red) is a common refrain I heard during my research. Despite the mutual admiration of the Tibetans and Americans, a series of misunderstandings marred the relationship. The United States was mainly interested in preventing the spread of Communism rather than providing serious and committed aid to Tibet.42 A second, and more serious, misunderstanding remains unexplored in most discussions of the resistance—namely, the importance of regional allegiances and identities within the Tibetan community.

Tibetan social and political divisions were far more complex than is often realized. The importance of such affiliations was not fully recognized by CIA officers involved in the Tibetan project. This oversight had a dual impact— first, it impaired the U.S. government’s ability to administer and advise the resistance; second, it complicated the internal dynamics and organization of the resistance, affecting relations with the United States and the trajectory of the resistance in general. Three factors help to explain this shortcoming. First, U.S. intelligence analysts had little information about Tibet. What they did know was based on British sources that downplayed the importance of regional variations and focused mainly on Lhasa. Although the British Chinese Consular Service had officials posted in eastern Tibet, the bulk of Britain’s information about Tibet was collected by officers associated with British India and focused on central Tibet. Second, the primary contact between the Americans and the Tibetans was Gyalo Thondup, who was from the northeast region of Amdo and thus not always sympathetic to Khampa systems of authority. Finally, only one CIA officer could speak any Tibetan.43 Communication was otherwise done through Tibetan and Mongolian interpreters, whose knowledge of English ranged from superb to rudimentary.

The CIA officers’ failure to recognize the importance of regional identity for the Tibetans was ironically at odds with the officers’ strong personal admiration of the soldiers they trained. According to resistance veterans, this misunderstanding proved disastrous in several respects. The CIA vetoed soldiers’ suggestions to organize operations around native-place and regional allegiances. On one occasion, a crack unit of guerrillas were sent against their wishes into an area of Tibet in which they did not have local support. They were ambushed by the Chinese, and all but one were killed.44 On a broader level, the administration of the resistance was hindered because of misinterpretations of connections between the different leaders of the resistance, and between the leaders and the soldiers. The CIA’s military-style ranking of the men was based on an achieved status, whereas among the guerrillas themselves achievement and military prowess did not outrank ascribed statuses. For the most part, the leaders were men with long-established social power that was legitimated through the same sort of personal and place connections that existed in Tibet prior to the Chinese invasion. The resistance force, despite being a unified army, retained strong elements of autonomy and allegiance based on native-place networks. The district-based loyalties of soldiers and battalions were at times subordinated to their allegiances to the united resistance, but at other times these loyalties were parallel to or even greater than their commitment to the army. U.S. efforts to organize battalions according to a place-neutral scheme were unsuccessful. Until the end, military resistance operations were primarily organized around native place-based encampments.

Region and the Tibetan Resistance

Prior to 1959, Tibet comprised a series of regions connected through shared cultural traditions, a shared religion, and a variety of political arrangements that linked the provinces with Lhasa. From 1642 through the 1950s, successive Dalai Lamas or their regents ruled Tibet. Under the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan state combined religion and politics in an administration that encompassed ritual and performative aspects of allegiance and extended a high degree of autonomy to certain areas within its sphere of influence.45 Organized hierarchically, the state was maintained in Lhasa and was represented in territories outside Lhasa in various forms. In most, though not all, of central Tibet, aristocratic and monastic leaders from Lhasa governed estates and the laborers attached to them. In other parts of Tibet, such as Kham, an estate system did not exist. Instead, affairs were mostly controlled by hereditary kings, chiefs, and lamas, some of whom belonged to lineages initially appointed by the Fifth Dalai Lama. Among them were leaders antagonistic to the central Tibetan government even when respectful of the Dalai Lama. As such, the structures and dynamics of state-local relations, far from being consistent throughout Tibet, varied widely in different regions as well as over time.

The region of Kham consists of more than thirty districts, referred to as pha yul. Each district is composed of a series of villages and monasteries of varying sizes and sects, often separated by huge mountain ranges and the rivers that cut through them. Systems of governance prior to 1950 varied by district—some were kingdoms, others were chiefdoms, and still others were governed by hereditary lamas.46 A handful of the districts were led by officials directly appointed by Lhasa or by the Chinese authorities in Sichuan. Relations between districts—and between monasteries—were often tense. Feuding was common, and bandits roamed the mountainous terrain. Differences between districts were marked in both secular and sacred ways, through dialect, clothing, and ornamentation, as well as through lamas, sects, and the deities associated with local landscapes. Not all districts or monasteries were assumed equal, and some were nominally or entirely under the stewardship of others. Despite the pronounced differences between regions, outside views of Tibet have tended to focus on Lhasa. To some extent, this has led to extrapolation from central Tibetan sociopolitical configurations to the rest of Tibet without taking due account of regional variations.

The Chushi Gangdrug resistance force was organized in ways that reflected the sociopolitical frameworks of eastern Tibet rather than the aristocratic and monastic hierarchies of central Tibet. On the battlefield, trust, loyalty, and familiarity were crucial. Guerrilla units were based on native-place affiliations, with troops from the same district forming a unit. Leaders of the units were often the same men who had been leaders in their districts—men from elite families or wealthy traders. Although these systems of power and authority were not designed to be as flexible or collaborative as the unified resistance required, they were the system used for military units during the entire period.

The “supreme leader” of the resistance was Andrug Gompo Tashi, a trader from the eastern Tibetan district of Lithang. Although some of the leaders of these native-place battalions had sociopolitical status greater than that of Andrug Gompo Tashi, his status as head of the Chushi Gangdrug resistance was unchallenged. As a result, an inordinate number of men who rose to positions of prominence within the resistance were from Andrug Gompo Tashi’s district of Lithang.

In addition to Andrug Gompo Tashi, Gyalo Thondup was the other major figure of the resistance. Gyalo Thondup was one of several intermediaries between the Tibetan and U.S. governments and was the main liaison between Chushi Gangdrug and the United States. Although other Tibetans had taken part in discussions with U.S. agents in both India and Nepal in the early 1950s regarding Tibetan resistance to the Chinese, Gyalo’s status as brother of the Dalai Lama trumped the connections that any other Tibetan had to offer. In the eyes of the U.S. government, Gyalo was not just an intermediary; he was the chief architect of the Tibetan resistance.47 However, the Chushi Gangdrug soldiers themselves did not always view Gyalo Thondup’s position so favorably. For the soldiers, Gyalo was more of a patron than a leader of the resistance, an intermediary of the highest status, responsible for managing U.S. aid. As the brother of the Dalai Lama and a native of the northeast region of Amdo, Gyalo Thondup was a worldly individual educated in China and a political figure who operated at levels well above those of the average resistance soldier and of their mostly provincial leaders (including Andrug Gompo Tashi). Hence, Gyalo was—and still is—seen as a benefactor of the resistance. In the minds of resistance soldiers, Gyalo was the unofficial and at times renegade official for the Tibetan government-in-exile who coordinated both Tibetan and external support for the resistance.

The status of patron is an esteemed one in Tibetan society. The contributions of a patron are acknowledged and praised, and the patron’s efforts bolster rather than detract from the authority of the group being sponsored. For resistance members, Gyalo Thondup’s contributions to the resistance did not outweigh those of Andrug Gompo Tashi but were assessed differently and were accorded different historical weight within the organization. In contrast, the CIA dealt with Chushi Gangdrug mostly through Gyalo Thondup, rather than taking account of the horizontal divisions within the group’s ranks or the authority of Andrug Gompo Tashi, whose influence continued well after his death in 1964.

In line with these trends in leadership and organization, the resistance saw itself as a mostly autonomous entity. In exile, veterans depict the resistance organization as having been an equal partner to, rather than subordinate of, the U.S. and Tibetan governments. The inability of the Tibetan government’s own army to fight against the PLA, along with the necessarily secret relationship between Chushi Gangdrug and Lhasa, enabled the resistance to enjoy a large measure of autonomy vis-à-vis the Tibetan government that carried over into exile. Indeed, relations between the resistance and the Tibetan government army were never more than lukewarm. Although some army officers joined the resistance, others had disdain for the guerrilla force.48 The Tibetan resistance movement was not a creation of the CIA, of Gyalo Thondup, of the Tibetan government, or even of Andrug Gompo Tashi. Rather, it was a grassroots organization formed in response to Chinese oppression. The managed autonomy that defined the Chushi Gangdrug battalions in Tibet continued into organizational efforts in exile. The many leaders of the group were assisted but not directed by outsiders.

This last point—the guerrillas’ view of the resistance as an autonomous organization—is not to be brushed aside. Time and again, former leaders and soldiers explained to me that the Chushi Gangdrug’s decisions about policy and actions were internal affairs. This was true of activities both inside and outside Tibet. For example, after the escape of the Dalai Lama into exile in March 1959 and almost a full year of battles with the PLA, many Chushi Gangdrug units had to flee to India. Once in India, the soldiers were not allowed to cross the border back into Tibet, and many took jobs building roads in Sikkim. Displeased with this situation and anxious to continue the struggle, they sent messages to Andrug Gompo Tashi and Gyalo Thondup in Kalimpong asking that a meeting be convened. More than 200 leaders and 3,000 soldiers of Chushi Gangdrug subsequently gathered in Gangtok to discuss their options, including the popular suggestion that they return to Tibet to resume fighting. The participants approved three major decisions: first, to appoint two Chushi Gangdrug representatives to each office of the Tibetan government-in-exile; second, to set up military operations in Mustang in neighboring Nepal; and third, to accept aid from the United States rather than Taiwan, which had tried to recruit Tibetans in India to serve in the Taiwanese army. The meeting in Gangtok, and especially the decision to continue sending men to the United States for military training and to establish the Mustang army camp, gave new life to Chushi Gangdrug operations in exile. The meeting instilled in many Tibetans an admiration of and hope in the United States that continues to this day. Although the admiration was mutual for Americans working closely with the Tibetans, sentiment at higher levels regarding Tibet was less personal and more practical—what could the Tibetans do for the United States?

Documents, Wristwatches, Histories

In November 1961, CIA Director Allen Dulles appeared at a meeting of the U.S. National Security Council’s Special Group carrying an unusual item— the bloodstained and bullet-riddled pouch of a Chinese army commander.49 No less graphic than the pouch was what it contained—more than 1,600 classified Chinese documents described as not merely an “intelligence goldmine” but “the best intelligence coup since the Korean War.”50 The pouch and documents were well traveled, having been carried on foot by Tibetan guerrillas out of Tibet through Nepal and into India, where they were whisked away to the United States on transport aircraft. The Tibetan soldiers who captured the documents were part of the Chushi Gangdrug volunteer army’s Mustang force.

The Tibetans did not enjoy uniform support in Washington.51 In the early 1960s, with the transition from the Eisenhower to the Kennedy administration, senior officials debated whether the covert operation in Tibet should be continued.52 Allen Dulles’ dramatic introduction of the blood-stained bag literally “shot through with explanation” could not have been better timed.53 The documents in the pouch were of priceless value to the U.S. government. At the time, little intelligence information existed about the PRC. China presented itself as a perfectly functioning state, one that was militarily secure, with a population that was flourishing. The documents revealed just the opposite: that the Great Leap Forward had failed catastrophically and had led to widespread famine in China, and that serious internal problems had arisen in the military and the party.54 The importance of these documents to the CIA was unparalleled, and the scholarly community responded in kind when the materials were released several years later.55 Nowhere, however, was it revealed how the U.S. government had obtained the documents. Although President John F. Kennedy approved the continuation of the Tibetan project, the story of the men who captured the documents remained a secret.

The Tibetan government was also interested in the documents, though for a different reason. After leaving Lhasa, the only evidence the Tibetan government could obtain of the atrocities committed by Chinese troops was the oral testimony of Tibetan refugees. These testimonies were valuable but not as valuable as hard documentary evidence. The materials captured by the guerrillas contained crucial and tragic confirmation of the magnitude of violence in Tibet. The documents showed that in Lhasa alone more than 87,000 Tibetans had been killed by the Chinese military from March 1959 through September 1960. This evidence of Chinese atrocities was invaluable for the Tibetan government when it presented its case in the diplomatic language of international law. For the Tibetan government-in-exile, as for the CIA, the substance of the documents was what mattered rather than tales of how and by whom they had been obtained. The Dalai Lama’s autobiography, published in 1990, indicates that the documents were “captured by Tibetan freedom fighters during the 1960s.”56

Considering the importance accorded to the documents by the U.S. and Tibetan governments, one might expect that the former guerrillas would highlight this event in their narrations of resistance history. But as I soon found, this is not the case at all. They neither begin nor end their accounts with any mention of the documents, and they often did not refer to them at all. Why is it that this particular achievement so valued by the U.S. and Tibetan governments, is not remotely as memorable for the former soldiers?

Following the 1959 Tibetan exodus into South Asia, the resistance operated out of Mustang, the ethnic Tibetan kingdom that jutted up from the borders of northern Nepal into Tibet. In Mustang, the men established camps from which they could periodically sneak across the border into Tibet, raiding army camps, dynamiting roads, stealing animals, and collecting information and transmitting it by radio to the United States. One of their goals was to ambush PLA convoys, kill the soldiers, and confiscate all their weapons, supplies, and materials. On one especially successful raid they captured a large pouch stuffed with documents. The documents were all in Chinese, a language that none of the Tibetans could read. A veteran named Lobsang Jampa was one of the few who did mention the documents to me. He recalled:

There was a man called Gen Rara. He was very popular among us. He led an attack on the Chinese and secured some very important documents from a Chinese official. This proved very useful to us. . . . We sent those documents on. But I don’t know what they were about.57