The Advent of British Educational System and English Language in the Indian Subcontinent: A Shift from Engraftment to Ultimate Implementation and Its Impact on Regional Vernaculars

by Muhammad Tufail Chandio, Saima Jafri, & Komal Ansari

International Research Journal of Arts & Humanities (IRJAH) Vol. 42

January 2014

Abstract

The research study critically traces the historical background of the introduction of the western education system with English as the medium of instruction in the Indian subcontinent and its impact on the teaching of various subjects and local languages in the postcolonial phase. It analyzes the transitional shift from the indigenous/regional vernaculars to engraftment (translating western knowledge into indigenous languages for teaching) and eventual shift to English as the medium of instruction, which thwarted the process of engraftment and development of indigenous languages. The study analyzes that how the education in the subcontinent was affected in the wake of diametrical shift in the British political policy from orientalism, engraftment, conciliation and consolidation to hostility, antagonism and oppression. Although, the study repudiates the popular myth of the revolutionary changes claimed by the British education system in the subcontinent, yet it establishes that how in the longer term it contributed to the academic, literary, social, political and economic advancement of the region. Nevertheless its repercussions for the regional languages were immense. The study reveals that how English, which was the language of power, authority and center, became a means of retaliation, communication and resistance at the hands of natives. The study, in its nature, is descriptive and historical one.

Key Words: British Colonial Education system, Vernaculars, Engraftment, English Language.

Introduction

The undertaken study focuses the introduction of English language in the educational system of the Indian subcontinent in the wake of the British colonization. The region remained under the indirect and direct rule of the British Empire for about three centuries. The colonizers used Eurocentric historical construct, English literature and English-based western educational system to justify and perpetuate the colonial rule. The pre-colonial educational system of the region was based on the indigenous languages viz. Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit and other vernaculars. Initially to avoid confrontation and resistance, the colonizers did not interfere in the educational system of the region. In the later period, the approach of engraftment was introduced, in which the content of the western knowledge were translated into the indigenous languages; however, there had been a prolonged controversy and polemical debate between the Conservatives (Orientalists) and the Reformists (Anglicists) over the education system and medium of instruction: the former preferred the oriental educational system and the engraftment of the western contents, whereas the latter were bent upon the introduction of the western educational system with English as the medium of instruction.

One of Voltaire's favorite teachers at the Jesuit college Louis-le-Grand in Paris was Father Rene Joseph DE TOURNEMINE (1661-1739), the chief editor of the journal Memoires de Trevoux. Father Tournemine had been involved in the controversy about the Chinese Rites that culminated in 1700 with the banning of several books on China at the Sorbonne. This so-called Querelle des rites [Google translate: Quarrel of rites.] had been accompanied by the publication of reams of pamphlets and books and is a striking example of public attention to oriental issues in Voltaire's youth and of their impact on the established religion in Europe (Etiemble 1966; Pinot 1971; Cummins 1993).

On the losing side of the rites controversy, which came to a peak one century after Ricci in Voltaire's school years, were those who agreed with his idea that the ancient Chinese had from remote antiquity venerated God and abandoned pure monotheism only much later under the influence of Persian magic (Daoism) and Indian idolatry (Buddhism). They liked to evoke Ricci's statement about having read with his own eyes in Chinese books that the ancient Chinese had worshipped a single supreme God. In order to explain how this pure ancient religion had degenerated into idolatry, they cited Ricci's Story about the dispatch in the year 65 C.E. of a Chinese embassy to the West in search of the true faith (Trigault 1617:120-21). Instead of bringing back the good news of Jesus, the story went, the Chinese ambassadors had stopped short on the way and returned infected with the idolatrous teachings of an Indian impostor called Fo (Buddha). In the following centuries, this doctrine had reportedly contaminated the whole of East Asia and turned people away from original monotheism. Since Ricci's Story was told in one of the seventeenth century's most widely translated and read books about Asia, Nicolas Trigault's edition of Ricci's History of the Christian Expedition to the Kingdom of China (first published in Latin in 1615), it had an enormous influence on the European perception of Asia's religious history.

Ricci's extremist successors, the so-called Jesuit figurists (see Chapter 5), sought to locate the ancient monotheistic creed of the Chinese not just in Confucian texts but also in the Daoist Daodejing (Book of the Way and Its Power) and of course in the book that some believed to be the oldest extant book of the world, the Yijing (or I-ching; Book of Changes).

These figurists included the French China missionaries Joachim Bouvet (1656-1730), the correspondent of Leibniz, and younger Jesuit colleagues like Joseph-Henri Premare (1666-1736) and Jean-Francois Foucquet (1665-1741), the man to whom Voltaire later falsely attributed the translation of his own "Chinese catechism." The Jesuits of the Ricci camp thought that since genuine monotheism had existed in a relatively pure state at least until the time of Confucius, their role as missionaries essentially consisted in reawakening the old faith, documenting its "prophecies" regarding Christ, identifying its goal and fulfillment as Christianity, and eradicating the causes of religious degeneration such as idolatry, magic, and superstition. Ritual vestiges of ancient monotheism were naturally exempted from the purge and subject to "accommodation."

By contrast, the extremists in the victorious opposite camp of the Chinese Rites controversy held that -- regardless of possible vestiges of monotheism and prediluvian science -- divine revelation came exclusively through the channels of Abraham and Moses, that is, the Hebrew tradition, and was fulfilled in Christianity. This meant that the Old and New Testaments were the sole genuine records of divine revelation and that all unconnected rites and practices were to be condemned. From this exclusivist perspective, the sacred scriptures of other nations could only contain fragments of divine wisdom if they had either plagiarized Judeo-Christian texts or aped their teachers and doctrines.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

The Minutes of Macaulay 1835 settled the issue in the favour of Reformists (Anglicists), and English was introduced as the medium of instruction. Macaulay reiterated that the western English-based educational system would groom a band of the natives who would be Indian in colour but English in taste and intellect and they would play the role of intermediary between the colonizers and the colonized. After the War of Independence (1857), the British government replaced the policy of reconciliation and cooperation with antagonism and oppression. This caused three major losses to the field of education and language teaching: the first, the gradual process of engraftment of western contents was stopped which, if continued, had enriched the indigenous languages with the modern knowledge; the second, the oriental knowledge went into the background as the colonial discourse belittled its worth and scope; the third, English dominated and overshadowed the indigenous languages and halted their progress and development.

When the natives started National Movements against the foreign rule, there occurred a dramatic shift in the status of English from the language of center to the periphery, from the language of power to the tool of retaliation, from the symbol of authority to subversion; moreover, it was altogether transformed from the tool of colonial, imperial and cultural indoctrination to the powerful means of protest and communication at the hands of the natives. This study upholds the issue of occidental versus oriental education system and traces its consequences.

Scope of the Study

The study traces the transitional and historical shift in the educational system of the Indian subcontinent from the oriental to occidental contents and pattern with English as the medium of instruction. The study provides fresh insight into the historical development of language and content teaching in the region. Besides, it also deals with the status, scope, contribution and impact of English language in the academic, political, social, economic and literary realms of the region.

Hypothesis

There is a significant impact of the western education system with English as the medium of instruction on the educational system of the Indian subcontinent in the wake of the British colonization.

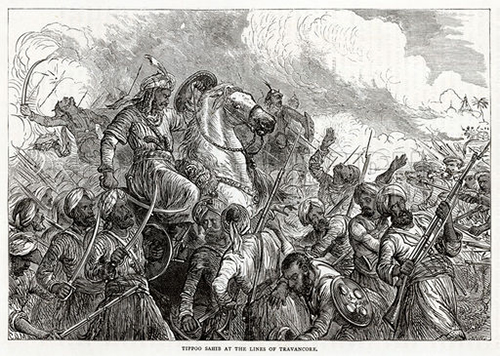

The British Colonization of the Indian Subcontinent

After the discovery of the Cape of Hope by a Portuguese navigator in 1498, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the English and the French East India Companies landed in the South Asia. The English East India Company dominated in the Indian subcontinent and outdid its rival European companies. The company had its army for the security and protection of the trade; however, the same military was used in the princely conflicts among the small states and the company was paid for it. With the passage of time, the company made contracts with these small states and provinces for their security and persuaded them not to keep their army on the pretext that the company would defend them. It served dual purpose: the company extended its trade in these states and got political power to intervene and settle the political affairs. Robert Clive defeated the French and their Indian allies and attacked on Bengal. His victory over Siraj-ud-Dawlah in the War of Plassey (1757) laid the foundation of British rule in India.

-- Fort William-India House Correspondence and Other Contemporary Papers Relating Thereto, Vol. I: 1748-1756, Edited by K. K. Datta, M.A., Ph.D., Professor of History, Patna University, Patna. Published for the National Archives of India by the Manager of Publications, Government of India, 1958

-- Full Proceedings of the Black Hole Debate, Bengal, Past & Present, Journal of the Calcutta Historical Society, Vol. XII. Jan – June, 1916

Diwan Act 1765 empowered the company to collect revenue and tax from Bengal, Behar and Orissa.

Provisions of the Diwan Act 1765 in India

by Google AI

Accessed: 8/30/24

In 1765, the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II granted the East India Company (EIC) the Diwani (revenue rights) of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This marked a significant milestone in the history of British colonialism in India.

Key Provisions

1. Diwani Rights: The EIC was appointed as the Diwan, responsible for collecting revenue from these provinces, with a fixed annual tribute of twenty-six lakhs of rupees to the Mughal Emperor.

2. Company Rule: The EIC assumed direct control over the diwani administration, replacing the autonomous nawabs and diwans. This marked the beginning of British colonial rule in Bengal.

3. End of Clive’s Double Government: In 1772, the EIC’s Court of Directors abolished the Clive’s Double Government system, where the Company and the nawabs shared power. Warren Hastings, the Governor, took direct control of the diwani administration, solidifying British rule.

Impact

The Diwan Act of 1765:

• Established British dominance over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa

• Marked the beginning of the East India Company’s expansion beyond trade to territorial control

• Set a precedent for future British territorial acquisitions in India

• Led to the eventual decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of British colonial rule in India

The news of making abnormal profit and misappropriation reached England, for that, Regulation Act 1773 was passed to monitor the business activities of the English merchants in India.

India's 1773 Regulation Act

by Google AI

Accessed: 8/30/24

The Regulation Act of 1773 was a significant piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament to regulate the activities of the East India Company (EIC) in India. The Act aimed to revamp the company’s governance and management, addressing concerns about its financial troubles, corruption, and lack of accountability.

Key Provisions:

1. Limited Company Dividends: The Act capped company dividends at 6% until the company repaid a £1.5m loan.

2. Restricted Court of Directors: The Court of Directors’ terms were limited to four years, ensuring greater accountability and rotation of leadership.

3. Prohibition on Private Trade: Company employees were banned from engaging in private trade or receiving gifts or bribes from Indians.

4. Establishment of a Governor-General: The Act created the position of Governor-General, responsible for overseeing the company’s administration in India, with the authority to issue orders and regulations.

5. Centralization of Power: The Act centralized power in the Governor-General, reducing the autonomy of local officials and the Court of Directors.

Impact:

1. First Step towards Parliamentary Control: The Regulation Act marked the beginning of parliamentary control over the EIC’s Indian administration, paving the way for further reforms.

2. Improved Governance: The Act introduced measures to reduce corruption and increase accountability, leading to a more transparent and efficient administration.

3. Limited Company’s Autonomy: The Act curtailed the company’s autonomy, making it more accountable to the British government and Parliament.

4. Prepared Ground for Future Reforms: The Regulation Act laid the groundwork for subsequent reforms, such as Pitt’s India Act of 1784, which further centralized power and introduced more significant changes to the company’s governance.

Conclusion: The Regulation Act of 1773 was a crucial step in the British Parliament’s efforts to regulate and control the East India Company’s activities in India. While it had its limitations, the Act introduced important reforms, including the establishment of a Governor-General and the prohibition on private trade, which helped to improve governance and reduce corruption.

The Court of Directors was constituted to deal with the affairs of the company and the members of the court were chosen through election process. Later on, William Pit[t] moved a resolution in the British Parliament in 1784 for bringing the company under the administrative control of the ministry. Thus, the company through the ministry was responsible to the British Parliament. From 1757 onwards, the British Government indirectly ruled India through the company but after the upsurge of 1857, the British Government terminated the company’s power and assumed its rule in India, hence India went under the direct rule of the British government, which ended in 1947. Brian (1996) reveals that the territory of about two hundred and eighty thousand square miles, equal to all Christian Europe, consisting of thirty millions of human race, were under the direct control of the East India Company. However, the native laid the foundation of the anti-British empire movements: both the Muslim and the Hindus, in harmony to the extent, jolted, questioned, frowned, and eventually up-rooted the British empires, which split the then Indian subcontinent into two separate states – India and Pakistan, the latter was further subdivided with the emergence of Bangladesh in 1971.

British Withdrawal from India in 1947

by Google AI

Accessed: 8/30/24

Based on the provided search results, here is a concise answer:

The British left India in 1947 due to a combination of factors, including:

1. Financial burden: World War II had severely damaged the British economy, making it difficult for them to maintain their colonial empire.

2. Local resistance: The Indian Independence movement, led by Mahatma Gandhi and others, had been gaining momentum, and the British realized that they were losing control.

3. Royal Indian Navy Mutiny (1946): This mutiny showed the British that they were no longer able to maintain control over the local armed forces, making their presence untenable.

4. Shift in global politics: The post-war world order was changing, and the British Empire was no longer the dominant power it once was.

5. Partition: The British decided to partition India into two separate countries, India and Pakistan, to accommodate the demands of Muslim leaders and to reduce the complexity of governing a diverse population.

Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, played a key role in negotiating the transfer of power and setting the date for independence, August 15, 1947. The British government, led by Prime Minister Clement Attlee, ultimately concluded that it was no longer feasible to maintain control over India.

Note that some sources, like Dr. Susmit Kumar’s claim, suggest that Hitler’s defeat in World War II and the subsequent shift in global politics contributed to the British decision to leave India. However, this perspective is not widely accepted and is not supported by the majority of historical accounts.

A Snapshot of the Pre and Post Colonial Indigenous Educational System

The pre-colonial Indian education system was based on oriental pattern consisting of Pathshalas, the madrassas, the Persian schools called Maktabs, in which Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit were mediums of instruction; later in 1829, Urdu was also added as a medium of instruction. With the advent of the British rule, the western education system based on European scientific knowledge and literature with English as the medium of instruction was introduced. Warren Hastings, Lord Bentinck, Charles Grant, Zachary Macaulay and William Wilberforce influenced the British policy of education in the region. Subsequently, Macaulay’s Minutes of 1935, Wood’s dispatch 1854, Hunter Commission 1882, Saddler Commission 1917, Hartog Committee 1929, Abbot and Wood Report 1937 and Sargent Report 1944 emphasized the superiority of occidental over oriental system of education.

Hartog Committee Report, 1929

by YourArticleLibrary

Accessed: 8/30/24

In 1929, the Hartog Committee submitted its report. This Committee was appointed to survey the growth of education in British India. It “devoted far more attention to mass education than Secondary and University Education”. The committee was not satisfied with the scanty growth of literacy in the country and highlighted the problem of ‘Wastage’ and ‘Stagnation’ at the primary level.

It mentioned that the great waste of money and efforts which resulted because of the pupils leaving their schools before completing the particular stage of education. Its conclusion was that “out of every 100 pupils (boys and girls) who were in class I in 1922-23, only 18 were reading in class IV in 1925-26. Thus resulted in a relapse into illiteracy. So, it suggested the following important measures for the improvement of primary education.

I. Adoption of the policy of consolidation in place of multiplication of schools;

II. Fixation of the duration of primary course to four years;

III. Improvement in the quality, training, status, pay, service condition of teachers;

IV. Relating the curricula and methods of teaching to the conditions of villages in which children live and read;

V. Adjustment of school hours and holidays to seasonal and local requirements;

VI. Increasing the number of Government inspection staff.

In the sphere of secondary education the Committee indicated a great waste of efforts due to the immense number of failures at the Matriculation Examination. It attributed that the laxity of promotion from one class to another in the earlier stages and persecution of higher education by incapable students in too large a number were the main factors of wastage.

So it suggested for the introduction of diversified course in middle schools meeting the requirements of majority of students. Further it suggested “the diversion of more boys to industrial and commercial careers at the end of the middle stage”. Besides, the Committee suggested for the improvement of University Education, Women Education, Education of Minorities and Backward classes etc.

The Committee gave a permanent shape to the educational policy of that period and attempted for consolidating and stabilizing education. The report was hailed as the torch bearer of Government efforts. It attempted to prove that a policy of expansion had proved ineffective and wasteful and that a policy of consolidation alone was suited to Indian conditions. However, the suggestions of the Committee could not be implemented effectively and the educational progress could not be maintained due to worldwide economic depression of 1930-31. Most of the recommendations remained mere pious hopes.

Abbot and Wood's 1937 Investigation Report

by Google AI

Accessed: 8/30/24

Abbot and Wood Report 1937: Recommendations for Vocational Education in India

The Abbot and Wood Report, submitted in 1937, was a comprehensive study on vocational [training in a special skill to be pursued in a trade] education in India. The report’s authors, A. Abott and S.H. Wood, were British experts invited by the Government of India to prepare a plan for vocational education in the country.

Key Recommendations

• Hierarchy of Vocational Institutions: The report suggested a complete hierarchy of vocational institutions parallel to the hierarchy of institutions imparting general education.

• Regional Vocational Areas: Vocational education should be organized according to the needs of various regional vocational areas, with no area considered less important.

• Main Regional Vocations: The organization of vocational education should prioritize main regional vocations, such as agriculture, industry, and commerce.

• Standardization: Vocational education should be considered at par with literary and science education, and its standard should be raised.

• Institutional Setup: The Government should establish vocational institutions in big cities and big vocational centers.

Junior and Senior Vocational Schools

• The junior vocational school should be considered equivalent to a high school, and the senior one should be equivalent to an intermediate college.

The Abbot and Wood Report played a significant role in shaping India’s vocational education system, leading to the establishment of polytechnics and other technical institutions. Its recommendations continue to influence India’s vocational education landscape to this day.

The Controversy over Educational System and the Medium of Instruction

There had been prolonged controversy and polemical debate between the Conservatives (Orientalists) and the Reformists (Anglicists) over the education system to be introduced in the colonized India. The Conservatives preferred the continuation of pre-colonial oriental education system after translating some content of European learnings into the classical languages like Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit or local vernaculars and they emphasized that these languages, as prevalent, should be continued as the medium of instruction. The Conservatives had the firsthand experience of India therefore they were very cautious and did not want to unnecessarily intervene or meddle with the sensitive issues like religion, culture and language. Conversely, the Anglicists intended to introduce the western education pattern, based on science and literature with English as the medium of instruction.

In addition, the missionary wished to bring the superstitious natives to Light and Truth through Christianity. Spear (1938) maintains though it was missionary that wanted to Anglicize the education system of India, yet the most powerful demand was raised by the champions of utilitarianism and free-trade, who wanted to invigorate the stagnant fabric of the Indian society with the infusion of western learning.

Thus, each faction wanted to reform India in accordance with its ideology and affiliation. The Reformists were the followers Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), the founder of utilitarian philosophy, and preferred the education system based on European science and literature. The Orientalists were orthodox hence very much prudent and scrupulous [?!], whereas the missionary ascertained that only Christianity could render salvation to the pagan and superstitious Indians.

A far more promising approach to the problem, indeed a short cut, seemed to be heralded in a letter to Jones from Lieutenant Francis Wilford, a surveyor and an enthusiastic student of all things oriental, who was based at Benares. Jones had been sent copies of inscriptions found at Ellora and written in Ashoka Brahmi, the still undeciphered pin-men. He had probably sent them to Wilford because Benares, the holy city of the Hindus, was the most likely place to find a Brahmin who might be able to read them. In 1793 Wilford announced that he had found just such a man:I have the honour to return to you the facsimile of several inscriptions with an explanation of them. I despaired at first of ever being able to decipher them... However, after many fruitless attempts on our part, we were so fortunate as to find at last an ancient sage, who gave us the key, and produced a book in Sanskrit, containing a great many ancient alphabets formerly in use in different parts of India. This was really a fortunate discovery, which hereafter may be of great service to us.

According to the ancient sage, most of Wilford's inscriptions related to the wanderings of the five heroic Pandava brothers from [url]the Mahabharata[/url]. At the unspecified time in question they were under an obligation not to converse with the rest of mankind; so their friends devised a method of communicating with them by "writing short and obscure sentences on rocks and stones in the wilderness and in characters previously agreed upon betwixt them." The sage happened to have the key to these characters in his code book; obligingly he transcribed them into Devanagari Sanskrit and then translated them.

To be fair to Wilford, he was a bit suspicious about this ingenious explanation of how the inscriptions got there. But he had no doubts that the deciphering and translation were genuine. "Our having been able to decipher them is a great point in my opinion, as it may hereafter lead to further discoveries, that may ultimately crown our labours with success." Above all, he had now located the code book, "a most fortunate circumstance."

Poor Wilford was the laughing stock of the Benares Brahmins for a whole decade. They had already fobbed him off with Sanskrit texts, later proved spurious, on the source of the Nile and the origin of Mecca. After the code book there was a geographical treatise on The Sacred Isles of the West, which included early Hindu reference to the British Isles. The Brahmins, to whom Sanskrit had so long remained a sacred prerogative, were getting their own back. One wonders how much Wilford paid his "ancient sage."

Jones was already a little suspicious of Wilford's sources, but on the code book, which was as much a fabrication as the translations supposedly based on it, he reserved judgment until he might see it. He never did. In fact it was never heard of again. But in spite of these disappointments Jones continued to believe that in time this oldest script would be deciphered. [Jones] had been sent a copy of the writings on the Delhi pillar and told a correspondent that they "drive me to despair; you are right, I doubt not, in thinking them foreign; I believe them to be Ethiopian and to have been imported a thousand years before Christ." It was not one of his more inspired guesses and at the time of his death the mystery of the inscriptions and of the monoliths was as dark as ever.

-- India Discovered, by John Keay

GENTLEMEN,

Before our entrance into the Disquisition promised at the close of my Ninth Annual Discourse, on the particular Advantages which may be derived from our concurrent Researches in Asia, it seems necessary to fix with precision the sense in which we mean to speak of advantage or utility.... though labour be clearly the lot of man in this world, yet, in the midst of his most active exertions, he cannot but feel the substantial benefit of every liberal amusement which may lull his passions to rest, and afford him a sort of repose, without the pain of total inaction, and the real usefulness of every pursuit which may enlarge and diversity his ideas, without interfering with the principal objects of his civil station or economical duties; nor should we wholly exclude even the trivial and worldly sense of utility, which too many consider as merely synonymous with lucre, but should reckon among useful objects those practical, and by no means illiberal arts, which may eventually conduce both to national and to private emolument. With a view then to advantages thus explained, let us examine every point in the whole circle of arts and sciences....

I. In the first place, we cannot surely deem it an inconsiderable advantage that all our historical researches have confirmed the Mosaic accounts of the primitive world; and our testimony on that subject ought to have the greater weight, because, if the result of our observations had been totally different, we should nevertheless have published them, not indeed with equal pleasure, but with equal confidence; for truth is mighty, and, whatever be its consequences, must always prevail; but, independently of our interest in corroborating the multiplied evidences of revealed religion, we could scarce gratify our minds with a more useful and rational entertainment than the contemplation of those wonderful revolutions in kingdoms and states which have happened within little more than four thousand years; revolutions, almost as fully demonstrative of an all-ruling Providence, as the structure of the universe, and the final causes which are discernible in its whole extent, and even in its minutest parts. Figure to your imaginations a moving picture of that eventful period, or rather, a succession of crowded scenes rapidly changed. Three families migrate in different courses from one region, and, in about four centuries, establish very distant governments and various modes of society: Egyptians, Indians, Goths, Phenicians, Celts, Greeks, Latians, Chinese, Peruvians, Mexicans, all sprung from the same immediate stem....

For example: A most beautiful poem by Somadeva, comprising a very long chain of instinctive and agreeable stories, begins with the famed revolution at Pataliputra, by the murder of king Nanda with his eight sons, and the usurpation of Chandragupta....

It is now clearly proved, that the first Purana contains an account of the deluge; between which and the Mohammedan conquests the history of genuine Hindu government must of course be comprehended....Now the age of Vicramaditya is given; and if we can fix on an Indian prince contemporary with Seleucus, we shall have three given points in the line of time between Rama, or the first Indian colony, and Chandrabija, the last Hindu monarch who reigned in Bahar; so that only eight hundred or a thousand years will remain almost wholly dark.... A Sanscrit [Sanskrit] history of the celebrated Vicramaditya was inspected at Benares by a Pandit, who would not have deceived me, and could not himself have been deceived; but the owner of the book is dead, and his family dispersed; nor have my friends in that city been able, with all their exertions, to procure a copy of it....for, while the abstract sciences are all truth, and the fine arts all fiction, we cannot but own, that in the details of history, truth and fiction are so blended as to be scarce distinguishable.

The practical use of history, in affording particular examples of civil and military wisdom, has been greatly exaggerated; but principles of action may certainly be collected from it; and even the narrative of wars and revolutions may serve as a lesson to nations, and an admonition to sovereigns....

Geography, astronomy, and chronology have, in this part of Asia, shared the fate of authentic history; and, like that, have been so masked and bedecked in the fantastic robes of mythology and metaphor, that the real system of Indian philosophers and mathematicians can scarce be distinguished: an accurate knowledge of Sanscrit [Sanskrit], and a confidential intercourse with learned Brahmens, are the only means of separating truth from fable; and we may expect the most important discoveries from two of our members, concerning whom it may be safely asserted, that if our Society should have produced no other advantage than the invitation given to them for the public display of their talents, we should have a claim to the thanks of our country and of all Europe....

Lieutenant Wilford has exhibited an interesting specimen of the geographical knowledge deducible from the Puranas, and will in time present you with so complete a treatise on the ancient world known to the Hindus, that the light acquired by the Greeks will appear but a glimmering in comparison of that he will diffuse....

The jurisprudence of the Hindus and Arabs being the field which I have chosen for my peculiar toil, you cannot expect that I should greatly enlarge your collection of historical knowledge; but I may be able to offer you some occasional tribute; and I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for though it could not have been Prayaga, where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja, which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks; nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erannoboas, which the accurate M. D'Ancille had pronounced to be the Yamuna; but this only difficulty was removed, when I found in a classical Sanscrit [Sanskrit] book, near 2000 years old, that Hiranyabahu, or golden armed, which the Greeks changed into Erannoboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona itself; though Megasthenes, from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately. This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandracottus the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes; and was no other than that very Sandracottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator; so that we have solved another problem, to which we before alluded, and may in round numbers consider the twelve and three hundredth years before Christ, as two certain epochs between Rama, who conquered Silan a few centuries after the flood, and Vicramaditya, who died at Ujjayini fifty-seven years before the beginning of our era.

Since these discussions would lead us too far, I proceed to the History of Nature.

-- Discourse X. Delivered February 28, 1793, P. 192, Excerpt from "Discourses Delivered Before the Asiatic Society: And Miscellaneous Papers, on The Religion, Poetry, Literature, Etc. of the Nations of India," by Sir William Jones1824

However, Thomas Babington Macaulay, the Law Member of Governor-General’s Council and the Chairman of the Committee of Public Instruction in Bengal, finally resolved the matter in the favour of the Anglicists in his minutes of 1835 by choosing the western line of education with English as the medium of instruction (Ashton, 1988: 23).

The Transition from Oriental to Occident Education System in the Region

In the early period, the East India Company (EIC) took initiatives only for providing education to the European children whose families traveled to India for business and commercial enterprise. Though, some of the upper class Indians enrolled their children in these schools. Benson (1972) mentions that the EIC did not encourage the educational development during the last quarter of the 18th and the first decade of the 19th century. The underlying prudence for employing such approach was the apprehension the company envisaged that the western education based on English language might ensue cultural conflict and subversion in the subjects (David, 1984; Rahim, 1986).

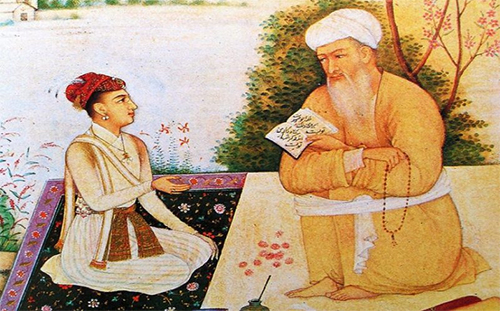

Initially the EIC patronized the prevailing oriental education system in India to avoid any confrontation with the local culture. Hastings’ (1773-85) pursuit of establishing the institutes for oriental studies based on Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic languages, was incorporation of that political ideology which was diametrically changed with the arrival of Lord Bentinck, the Governor-General during 1828-1835 (Rosselli, 1974). Viswanathan (1989) maintains that pro-oriental approach was an essential political strategy to harmonize the natives with the expanding British rule in India. To obtain such goals, the refined and acculturated band of English officers was appointed in India for the cultivation of cultural synthesis and forbearing to obliterate the feelings of foreboding (quoted by Pachori, 1990). Kopf (1969) adds that Hastings believed that those officers would have sympathetic outlook and broader understanding of the culture, laws and traditions of the Indian society, hence they would wield their power prudently. However, during the last quarter of the 18th and the first quarter of the 19th century, this approach was diametrically changed by the liberal reformists and the European education system based on English language was introduced in the colonized Indian subcontinent. They leveled their arguments on the grounds that the subject should acquaint themselves with western knowledge and culture for their assimilation with the rulers and not the vice versa (Clive, 1973). It indeed was a paradigm shift in the attitude of British towards India from “interest and appreciation to criticism and disdain”, which got momentous effect after the arrival of Lord Bentinck. Macaulay once mentioned in the House of Common that it was better to trade with the civilized people than rule over the savages.

The Role of the Missionary

The missionary, though not with official permission, started proselytizing the people in the 18th century. William Carry [Carey] translated Ramayana and Sanskrit grammar book. Besides, missionary established vocational schools where reading of the Bible was compulsory. The Bible was also translated into the indigenous languages. These institutes provided religious and vocational education to the children of the converts to earn their livelihood. The majority of the converts belonged to the lower Indian class (Chatterji, 1983). Thus, English language and contents first time got their roots in the Indian education system.

Charles Grant, Zachary Macaulay and William Wilberforce were in the favour of English education system in India. Wilberforce moved a resolution in the British Parliament in 1773 for introducing English education system in India so that the subjects could be uplifted morally, socially, politically and religiously. The explicit content and intention of converting people into Christianity led the parliament to disapprove the resolution. Besides, the parliament was prudent enough and did not want cultural and religious confrontation with the natives.

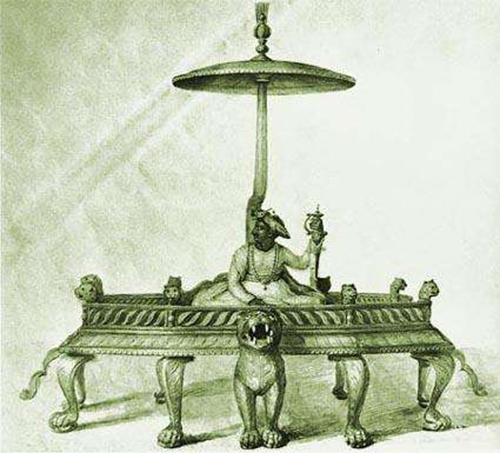

The Pro-Oriental Phase

Warren Hastings was appointed as the governor of Fort William, Calcutta in April 1772, he had much reverence for Indian culture and religion in general and Indian philosophy and literature in particular. He believed in the policy of consolidation and conciliation. He took initiatives for the translation of the Bhagavad Gita and the Mahabharata. Wilkin translated the Bhagavad Gita and Major Rennel, the inventor of printing type of Bengali and Persian script, wrote The Bengal Atlas. Hastings founded “Asiatic Society of Bengal” which rendered integral service to Indian culture and history. In addition, Hastings founded the Calcutta Madrassa in 1781 and the Benares Sanskrit College in 1791 to encourage oriental learning for the natives. The Orientalists were not in the favour of any covert or overt support for the promotion of missionary activities in India, because they knew it would be counterproductive and would beget dissatisfaction and confrontation. Some of the parliamentarians were of the opinion that the idea of educating colonies might not be carried further as they had already lost colonies after educating them – the experience of losing America was fresh in their memory.

The First Official Step: Leading from Oriental Knowledge to Engraftment of Western Contents

The first official blueprint for Indian education system was presented by Charles Grant, the director of EIC, in 1792. He is regarded as father of modern education in India. He was pro-Christian and had strong conviction that if the natives accepted Christianity they would adhere to the culture, politics, economic system and language of their rulers without any resistance or contempt. For him, Christianity, English language and western learning were the tools to mould the Indian natives morally, politically, socially, and religiously (Kirshnaswamy and Lalitah, 2006:12). Charles Grants’ treatise: Observation on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain (1792) was in tune with evangelical stance to convince the British parliament for introducing English education and missionary activities in India for the stability of the British rule.

However, missionaries were not happy with the Oriental system of education. They supported the Anglicists for introducing European knowledge of science and literature with English as the medium of instruction. Although, the missionaries approached the British Parliament to seek permission for conducting missionary activities in India, yet given to the policy of conciliation and consolidation, the parliament did not overtly support the missionary activities in the region.

Charles Grant was appointed as the Chairman of EIC in 1805, Deputy Chairman in 1807-1808 and again was appointed as Chairman in 1809. This appointment remained in the favour of both Anglicists and missionary. The Charter Act of 1813 determined that English would be incorporated in Indian schools in coexistence with the local vernaculars. Thus, the English education of science and art would gradually be “engrafted” to produce a class of elite that could serve as cultural intermediaries between the rulers and the ruled. Besides, it was envisaged that European education would boost the moral and social development of the Indians. The missionary now overtly continued its activities as the resolution included religious and moral uplift of the natives. Charles Grant made English as the medium of instruction; science, literature and the content of Christianity were used for the cultural indoctrination and transplantation so that the British could rule peacefully over Indians. In the follow up of the 1773 resolution, a Charter was passed in 1823 which made the government bound to spend at least one lac rupees for the education in India.

James Mill, the senior officer of the company in London during 1819-1836, published a book: History of British India in 1817 based on the utilitarian outlook upon the Indian society. The company’s dispatch of 1824, written by Mill on the behalf of the company, was imbued with Mills’ utilitarian convictions, and it deprecated the company’s policy of “engraftment”. He reiterated that the objectives of education should not be to disseminate Islamic or Hindu learning “but the useful knowledge.” (Zastoupil & Moir, 1999:116). Though Mill was in concord with Charles Grant regarding the teaching of European knowledge of science and literature and rejected the oriental studies yet he, unlike Charles Grant, did not support the implementation of English as the medium of instruction, but suggested that the translation of European knowledge into classical or local Indian vernaculars would yield fruitful harvest moreover in abundance (Zastoupil, 1994). In the response of Mills’ dispatch, the Committee of Public Instructions submitted the note of dissent that the prevailing dislike against the western education was a hindrance in its implementation. The note succinctly mentioned that any innovation in the education system might invoke the public prejudice and end in confrontation (Zastoupil & Moir, 1999:121). It was further reported that even the elite class nourished in the traditional education system would not favour the western education, until such favour was gained from the elite class in particular and society in general. The explicit advocacy and implementation of western education would endanger the peaceful rule in India.

Though there was conspicuous pressure from the middle class Hindu for learning in English, but the Committee of Public Instructions, being dominated by the Orientalists, was reluctant to favour the Anglicists. Majumdar (1955) testifies that the establishment of Hindu College at Calcutta for the higher education in English was the manifestation of growing interest of the public in English learning. Frykenberg (1986) adds that the same demand was incorporated in the private schools of Madras to teach rudiments of English language. In addition, the intellects like Rammohan Roy also preferred and demanded the education system based on western science and literature (Zastoupil & Moir, 1999).

The controversy between the Orientalists and Anglicists still continued but owing to the Gurkhas and Marathas wars during 1813- 1823, the education and other work of development could not receive serious consideration. In 1823, a committee was constituted consisting of the members of both Orientalists and Anglicists to settle the issues regarding education policy and system in India. The committee during 1823-1833 recognized the Calcutta Madrassa, Benares Sanskrit College and established Sanskrit College at Pona in 1821 and two Oriental colleges at Agra in 1823. The Oriental schools were asked to translate the books from English into Indian classical languages. The EIC was interested in trade, the British government endeavoured for the expansion of empire, whereas the missionary strove for conversion. Their interests were mutually dependent therefore missionary also succeeded in getting covert support from the government.

The Establishment of Missionary Schools

The missionary schools were established in India during 1815-1840 that included the Baptist Mission School 1815, the Seramore College 1818, the London Missionary Society’s School 1818, the Bishop College at Sibpur 1820, the Calcutta Society’s School 1819, the Jaya Narayan School and Ghoshal’s English School at Benars 1818. The most prominent one was the General Assembly’s Institution 1830 founded by the Scottish missionary headed by Alexander Duff, who was of the opinion that for converting people in Christianity, European knowledge and English language could be used as tools in the Indian education system. Duff and the missionary were very critical of “godless policy” of the British government in India.

The English-based Schools vis-à-vis the Demand of the Natives

The government started English classes at Calcutta Madrassa, the Benares Sanskrit College, Delhi College and Agra College during 1824-35. The young Indians were very much keen interested in English education based on the knowledge of science and art. They regarded it as Indian Renaissance. The English newspapers were published in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay during 1780-95. They Indian were incentivized to read and write in English. Owing to the increasing demand, the natives established the Hindu College in 1817 in Calcutta to impart education in English. The then chief justice of Supreme Court of Calcutta entertained a petition from a group of people who demanded for the provision of education based on European knowledge of science and art.

Raja Rammohan Roy, the prominent Indian figure and now regarded as the founder of modern India, also demanded for the education of science, mathematics, medicine, law and art, because he was of the opinion that Indian society could not progress until it was provided with the modern education. He supported English utilitarian approach in education and opposed the orthodox system dominated by the pundits, but he did not oppose the knowledge of Sanskrit. He was liberal and enlightened who struggled against the tradition of satti, self -immolation by a wife at the funeral pyre of her husband, child marriage and he fought for the rights of women in property and equal treatment in the society (Reena Chatterji, 1983). Thus, the demand for the education based on European subjects translated into Indian classical languages was manipulated to start education in English language. Lord Bentinck, who was friend of Charles Grant, was appointed as governor-general in 1828. He took initiatives for making English as the official language in India. Besides, both the company and British government also needed natives having skills in English language to run the affairs of government and company, because the number of English present in India did not meet the requirement. The committee, constituted for the settlement of line of education and language in India, remained divided in two ideological factions and the Orientalists and Anglicists could not reach to any feasible conclusion unanimously.

Frykenberg (1988) reveals that owing to mounting pressure from both the Indian and the British reformists during the first quarter of the 19th century, western knowledge and English language as the medium of instruction were introduced in the Indian subcontinent. With appointment of Lord Bentinck as the Governor-General and Charles Trevelyan, the brother in law of Macaulay, at the London office of GCPI in place of Wilson, the Orientalists were relegated in the background and Hastings’ policy of conciliation and consolidation was thwarted (Washbrook, 1999).

The Minutes of Macaulay (1835)

Lord Bentinck was appointed to squeeze the expenditures of the company. In the pursuit of the same, he introduced some reforms in which the traditions of satti and child marriages were abolished. Meanwhile, Charles Trevelyan after assuming his charge in London depreciated the oriental model of education in India (Fisher, 1919) and called the oriental pattern as “sleepy, sluggish, inanimate machines” (Hilliker, 1974:282). He further corresponded with Lord Bentinck for the Romanizing of Indian vernaculars and implementing “our language, our learning, and ultimately our religion” (Philips, 1977: 1239). For educational reform, he appointed Thomas Babington Macaulay, the Law Member of Governor-General’s Council, as the Chairman of the Committee of Public Instruction in Bengal, who finally resolved the matter in the favour of the Anglicists by choosing the western line of education in his minutes of 1835 regarded as “the manifesto of English education in India”.

Ghosh (1995) argues that there is no documented proof, but it cannot be ruled out that Macaulay before writing his minutes must have read Charles Grant’s “Observation”. As the minutes were very much tuned with line of action presented in the work of Charles Grant. Clive (1973) adds that Zachary, Macaulay’s father, was close associate of Charles Grant. Charles Jr., the son of Charles Grant, was intimate friend of Macaulay, therefore, the evangelical influence cannot be ruled out altogether. The Bentinck-Macaulay educational reforms were already planned and pre-conceived. Macaulay just officially produced it in black and white form and even its time was also decided. Bentinck knew that there would be much hue and cry in the wake of implementation of western education pattern and English language. Therefore, he chose the time when his tenure of governor-generalship was at end. Because, in past when he introduced some reforms in Madras, at the protest of the people he was removed from his office. So avoiding the replica at the end of his tenure, he implemented the recommendations made in the minutes of Macaulay without further delay and discussion.

Macaulay founded his arguments on the bases of inherit quality of western knowledge of literature and science. He provided a justification for imposing English language that it was another anomaly as it was strange phenomenon the British government ruled a country, thousands miles away having no cultural, social, linguistic and political affinity or sound reasons, where the subjects belonged to different caste, colour, religion, culture and political system. As the rule of British was an exception likewise the decision of making English as the medium of instruction was another strange step in the midst of prevailing political anomaly (Bailey, 1991:137). Besides, he further emphasized that Indian natives also demanded for English to build their career in the government services.

Lord Bentinck approved the minutes forthwith and sent to the Board of Directors, John Stuart Mill critically deprecated the proposal and suggested for the continuity of the past policy of “engraftment”. The proposal of Mill was sent to Sir John Hobhouse, the President of the Board and an ardent admirer of Macaulay. He directly contacted the Directors and asked them to give their assent without any comments or critique. After two months Sir John Hobhouse showed strong objection on the draft of Mill in his letter to James Carnac, the Chairman of the company (Zastoupil & Moir, 1999). Thus, in the follow up of the minutes, the resolution was passed in which promotion of European science and literature was made essential and all the funds were reserved only for English education (Zastoupil & Moir, 1999: 195). It all was done to have political and social control over the subjects by mesmerizing and influencing them with European knowledge (Pennycook, 1994:102-03).