Part 2 of 2

The Impact of Macaulay’s Minutes on the Classical and Local Languages

The minutes, in clandestine manner, suggested for the abolition of Sanskrit College and Calcutta Madrassa. It was explicitly mentioned that the funds for the printing of books in Arabic and Sanskrit and the stipends of the students pursuing oriental studies should be discontinued. As a result, the institutes imparting education in the classical and regional vernaculars were affected: their funds were curtailed on the pretext of investment in English education system. Besides, the stipends granted to Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian language students were also curtailed. English language replaced Persian in office, court, administration and diplomacy. Onwards, only those having western education and competence in English language were able to qualify job requirements, which increased the demand of English in the region. To reduce the expenditures of the company, Bentinck wanted to replace the British expatriates with Indian natives, for that he introduced educational reforms and got this sub-clause included in the Act of 1833 that appointment in government post will be purely on qualification “irrespective of religion, birth, descent or colour” (Adams & Adams, 1971:167). The job incentives aggrandized the demand of English in India (Mukherjee, 1989).

Cheshire asserts that English was used as a political tool to colonize and exploit but it has become the symbol of social superiority and status after the end of colonization (Cheshire, 1991: 6). But Kachru (1986b:136) maintains that it depends that who used English language, it was a tool in the hands of the colonizers for economic exploitation, cultural indoctrination, dislocation of indigenous culture and lingocide; whereas for nationalist, it became medium, link and window to the world to champion their cause and instill political awareness in the nation during the movement of liberty and independence to dismantle colonization.

Three Phases of the Introduction of English Language and Its Development

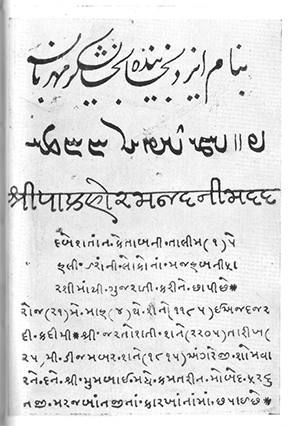

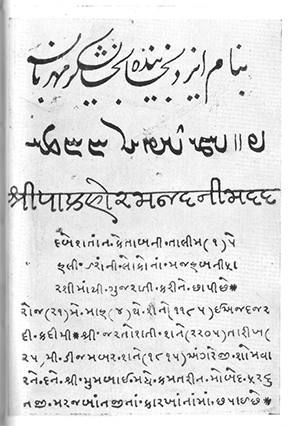

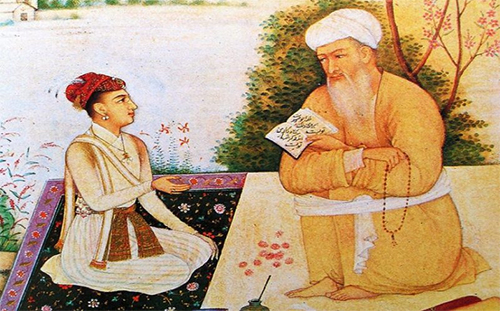

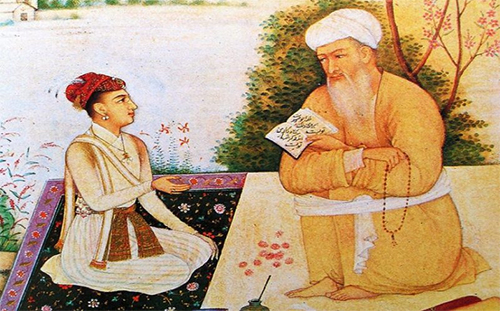

Kachru maintains that English was introduced in three phases: the first, by Christian missionary around 1614. The second, at the demand of the public and important figures in the 18th century, Raja Rammohan Roy (1772-1833) and Rajunath Hari Navalkar (fl.1770) were the chief exponents who supported the western education system, as they believed, it would strengthen the people socially, politically and economically, whereas, the knowledge of vernaculars would not help the native to obtain these goals (Kachru, 1983:67-68). Roy, in his letter to Lord Amherst (1773-1857) written in 1823, suggested that the investment should be made for the western knowledge on priority basis than the vernaculars. This letter was presented as the proof of public demand for western knowledge. Roy considered European knowledge essential for the social development and uplift. He believed that English language would serve as a “key to all knowledge”, which would be useful for Indian (Bailey, 1991:136). Roy wanted Indians to be educated with the knowledge of mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry, anatomy and other useful sciences (Kachru, 1983:68). The third phase began with the Government policy in 1765, when the East India Company’s authority was stabilized (Kachru, 1983: 21-22).

Lord Bentinck, the governor-general in India, supported by Lord Macaulay initiated some social reforms in India in the beginning of the 19th century. English was used as official language in higher courts, for record-keeping and as the medium of instruction for the cultivation of western learning and science (The New Encyclopedia Britannica (NEB), 1974: 403). Thus, English was used as the medium of instruction in law, higher education, administration, commercial enterprise, science, technology, business and trade because the indigenous vernaculars did not have adequate stuff to meet the nature of demand these fields posed so for.

The Outcome and Implication of the Educational Reform

After the declaration of English as the medium of instruction and administrative affairs, it anglicized the education system of India even in alien sociolinguistic and cultural settings. Moss reported that the British government allocated funds for uplifting education in 1813. The Hindu college was set up in Culcuta in 1816, followed by the Culcuta Medical College. In the 1840, and 1850 under Lord Dalhousie there was a great emphasis on primary education and high schools. Three universities were opened by 1857 as well as the Roorkee College of Engineering (Moss, 1999:76). Mubarak (2008) adds: "For the subservience of the mind of the local people, the British government introduced English as medium of instruction in the schools and colleges especially in the higher educational institutions. In the pursuit of the same, the universities were founded in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras in 1857, Punjab in 1882; while in 1887, more universities were set up in Allahabad. These universities catered knowledge to the students belonging to the upper middle class who had deep craving for government jobs." (P: 5).

The missionary from America and England initially established colleges for boys, but in the 20th century colleges for women were also founded in Madras, Lucknow and Lahore to cater education to the children of the converts along with their financial support. The English reformists also provided western education in their institutes with no intention of conversion. Henceforth, English was the language of office, court, press, middle bourgeois class and administration. The English newspapers started receiving wide readership and Indian literature in English also remarkably developed as being the logical consequence of encounter with English language (Kachru 1983: 69). He further mentions that English established its significant role in politics, court and in the domain of national administrative institutes, which remained dominant over the vernaculars even after the cessation of colonization (Kachru, 1986a:8). During the National Movement in 1920, despite anti-English sentiment, English was used as the language of protest and upsurge against the colonizers. Political leaders like Gandhi, who endeavored for the revival of local vernaculars, also chose English to communicate the upper class (ibid, p.8).

In 1880, approximately eight thousand pupils passed high school education, whereas the number of secondary education pass-out was almost 500,000 (five lac) (James, 1994). Vohra (2001:94) presents the education classification and pattern prevalent in the British India. The students after passing vernacular primary education joined Anglo-vernacular high school for the secondary education. At the completion of the secondary education, they had the possibility of seeking admission in one of 140 state-run or private colleges. In 1901, about 17000 students were enrolled in these colleges. The education system, British government introduced in India, groomed a number of intellectual figures but it also produced “a vast class of semi-educated, low-paid English speaking subordinates.” (ibid, p.68). Vohra mentions that English language provided a common means of communication to the people of India where there were “179 languages, 544 major dialects and thousands of dialects” (Vohra, 2001:94).

The Attitude of the Hindus and the Muslims towards English-based Education System

The Hindus, particularly Brahmans, were very much inclined to the British education system, whereas the Muslim refused to join these schools for long period, because they were hostile to English language as it replaced Persian language and the Muslim-ruler-introduced education system. They cherished the nostalgia of past education system and strove for its revival. The English dethroned the Muslim Mughal king, snatched power and colonized the land, therefore, they always held the Muslims in suspect. Because of this, the English interpreted the Muslims as the perpetrator of 1857 upheaval. The edge in education strengthened the Hindu community, and they dominated the politics of the country but Brahmans were again at lead. Thus, the education provided a way for social, political uplift and upward mobility, but it was the matter of opportunity for those who could avail it. Those, who failed to have access to the British education owing to whatsoever reason, lagged and lingered behind and could not acquire high slot in the social vertical or horizontal mobility. Dumont (1980:323) mentions that the Muslims were not happy with the replacement of Persian with English, they remained detached from both English education system and English language. As a result, the Hindu dominated the political and administrative fronts.

The Legacy of the British English

The British India government’s priority was rather running administration and draining wealth by developing trade than making arrangement for the learning of the Queen’s English. However, the present Indian English is very much influenced by the British English, especially Scottish English dialect, which has a pronounced “r” and trilled “r”. The Received Pronunciation (RP) or BBC English is also emulated by some people; nevertheless, the Indian dialect has also established its recognition as a distinct dialect even during the period of British imperialism. Besides, the British and Indian dialects, the American English has also got official acceptance, when the Indian students went to study in the universities of America rather than UK. The American English spellings and structures are common phenomena in scientific and technical scholarship and research studies; whereas the British English still pre-dominates the other fields of life. The survey conducted reveals that 70% preferred RP as the suitable pattern for Indian English, 10% opted American English and 17% liked distinctive Indian dialect (Das and Patra, 2009: 29-31).

The legacy of the East India Company still pervades the modern day Indian official correspondence: the phrases like “do the needful” or “you will be intimated shortly” still find frequent mention in the official correspondence. Malcolm Muggeridge, the English Journalist, writer and wit, added witty remarks that the last Englishman would be Indian (Das and Patra, 2009:30). In Pakistan, RP is preferred in English medium schools however the impact of local accent cannot be altogether ruled out.

Antithetical Status of English Language: From the Tool of Power to the Means of Protest and Communication

The story of English in the Indian subcontinent had antithetical characteristics: it was introduced by the British colonizers as the language of power, but it was used as the language of retaliation during the national movement in India. It was the language of invaders but was absorbed by the natives at great deal. It was the language of authority at the hands of the colonizers but the natives subverted its course. It has evolved from the tool of imperial, colonial and cultural indoctrination to powerful means of communication. English was used as the medium of instruction in the British Indian westernized education system, yet it served to the cause of both of the colonizers and the colonized: from central to the periphery and vice versa. The center, the British, used it to create a class tuned with the western outlook to regard the colonizers as the true benefactors; conversely, the periphery, the colonized, subverted it to translate their grievances and abhorrence against the colonialism. English, in the Indian subcontinent, immensely influenced the cultural outlook with ambivalent phenomenon of both loss and gain. However, after the revolution of information technology, the role of English language has remained highly powerful, which enables the people of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh to have direct interaction with the international community by employing English language as a neutral source of communication. In this connection, they have even excelled the advanced nations like China, Russia and Japan. After realizing its importance and shedding the colonial indifference, the countries of the Indian subcontinent are using it as economic, political and social necessity. The English language has been separated from its master, the colonizers, and it has been brought down to serve the cause of the masses; henceforth, it has no longer remained the language of classes but of masses.

Annika Hohenthal (2003) maintains, “In the same country the English language can be characterized by different terms representing the power of the language: Positive/Negative, National identity, Antinationalism, Literary renaissance, Anti-native culture, Cultural mirror (for native cultures), Materialism, Modernization, Westernization, Liberalism, Rootlesness, Universalism, Ethnocentrism, Technology, Permissiveness, Science, Divisiveness, Mobility, Alienation, etc.”

There has been a great deal of Indian natives who had astonished command over English, whose speeches and creative writings bear strong evidence of their mastery of style and articulation of language. Among them: Nobel prize winner in literature (1913) Rabindranath Tagore, C Rajagopalachari, Sri Aurbindo, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohandas Gandhi, Swami Vivekananda, R.K. Narayan, the eminent novelist, and Sarvepali Radhakrishanan. Following these precursors, there emerged some prominent figures who claimed world -wide recognition in the contemporary literature which include: Vikram Seth and Salman Rushdie, the Booker prize winner, Arundahti Roy, the author of international bestseller “The God of Small Things” (1997), Kiran Desai, Jhumpa Lahiri, Pulitzer Prize Winner, and V.S Naipal, the Noble Prize Winner (2001). From Pakistan, Ahmed Ali, Mumtaz Shahnawaz, Bapsi Sidhwa, Sara Suleri, Tariq Ali, Muhammad Hanif, Zaib-un-Nisa Hamidullah, Rukhsana Ahmad, Bina Shah, Tahira Naqvi, Uzma Aslam Khan, Kamila Shamshie and many other writer of international acclaim have showed the hallmarks of their ingenuity and creative verve in English language with distinctive mark of creative use of language, variety of style and deep artistic innovation.

In post-independence period, English has claimed significant importance in office, court, science, technology, trade, commerce, business, law, state affairs and transaction of whatsoever nature. English is the medium of instructions in all up standard schools, colleges and universities. English has asserted its significance in the national literature and national language policy. Realizing its global significance, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh have equally and unequivocally effected relentless pursuit for the acquisition of the language competence and skills. India is considered the third largest English book producing country after the US and the UK, and the largest number of books is published in English. India is a vast nation and in term of number of English speakers, it ranks third in the world after the USA and the UK. An estimated 4 percent of the population uses English; though this may seem like a small number, it consists of about 40 million people and this small segment of the population dominates the domains of professional and social prestige. Kachru (1997:68-69) states that there is an overwhelming majority consisting of 350 million in Asia that uses English. India is the third largest English-using country after the United Kingdom and America. The Indian English is closer to the British English, because it originated from that style. With the influx of globalization, American English has also influenced the youth and other sphere of professional fields. However, Indian English can neither be classified as American nor British English because after being intermingled with other Indian languages it is emerged with its own distinct flavor. This has made several scholars realize that it cannot be equated with either. In Pakistan, English language significantly dominates every walk of life, yet its scope and usefulness for the Pakistani English writers is still of the greater importance.

Conclusion

The education and English language policy in the Indian subcontinent varied from time to time and was subject to the political and ideological affiliation of the British government representatives in the region. As Warren Hastings was in the favour of orientalism, engraftment, conciliation and consolidation, whereas Cornwallis thwarted that approach and preferred the gap between the rulers and the ruled ones. He asserted the superiority of the English race and kept the colonized in abject humiliation. He did not trust the natives to be appointed at higher positions. With the appointment of Richard Wellseley, the policy of Hastings was revived and his successors followed him but Lord Bentinck along with Thomas Babington Macaulay hit the last nail in the coffin of Anglo-oriental controversy and by abandoning the policy of “engraftment” officially imposed the western education system with English as the medium of instruction.

The Directors’ dispatch in 1841 was a retreat from the strict stance of Macaulay (Carson, 1999). In 1854, Sir Charles Wood dispatched for the enrichment of indigenous vernaculars and making them worth-instructing for the western learnings. Woods emphasized that the core of argument lied in the fact that main objective was the diffusion of the learning of western science and literature in the Indian education system not the promotion of English language. Therefore, the indigenous vernaculars should be enriched for medium of instruction through the translation of the European knowledge. Woods policy remained central until the Act of 1919 was passed, in which the control of education was handed over to the Indian ministry and provincial legislation. In the Education Conference of 1927, the pro-vernacular policy received endorsement (Whitehead, 1991). Mwiria (1991) maintains that policy of promotion elementary vernacular education was also devised to perpetuate the British rule in India. Despite all efforts, Indian education was regarded as second rate in comparison with the education provided in England. It remained rather quantitative than qualitative. It could not produce the class of cultural intermediaries, Macaulay envisaged; however it ended with the hordes of Babus – the band of semi-educated cult taught and trained for routine office work.

The British education system, for what there was much debate and consumed much attention of the British Parliament, could only literate a small number of the natives. The literacy rate in 1911 was only 6%, which gained two points up to 1931and became 8%. In 1947, when India became independent its literacy rate was only 11%. The enrollment in universities or the degree-awarding institutes was also very low. In 1935, only 4 out of 10,000 people were enrolled in any degree awarding higher education institute. Besides the literacy rate, the quantity of published books and number of publications also help to estimate the real standing of a nation. In 1935, only sixteen thousand books were published for the nation consisting over 350 million people, the ratio stands: one book for twenty thousand people.

English influenced Indian subcontinent religiously, culturally, socially, politically and academically. The indigenous vernaculars were affected, as the emphasis shifted to English language. As a result, the translation of western knowledge into local vernaculars remained inadequate. It introduced innovation in teaching pedagogy, but owing to religious prejudice or differences, the religious education institutes remained stuck to age-old contents and methodology. It was the parsimony of British government in India, which wielded adverse impact on the local vernaculars, if the government had allocated sufficient funds, there had been no reason for the Anglo-Oriental controversy; the both could have developed in parallel. The low standard of Indian elementary education was because of negligent, parsimonious and apathetic attitude of the British towards India (Mayhew, 1926). Perhaps, it could not produce the class of cultural intermediaries as Macaulay envisaged, but it nourished the hordes of babus – the semi-educated clerical staff for routine office work.

English and European learnings served the cause of both the colonizers in the beginning and the colonized in the end. English was a socio-political tool at the disposal of the colonizers to wield power and exercise their writ. Later on, the same was used by the periphery against the center to challenge its writ and vent their dissatisfaction. The mass education mitigated the difference of class; urbanization integrated the people of various factions and classes. English provided a common communication ground to the people of different religions and vernaculars, to some extent also united them. Such cultural synthesis was manifest in the national movement of independence, in which the Hindu, the Muslim and the Jain strove against the British rule. Besides, English was used to record their grievances, dissatisfaction and protest at national and international level.

English provided access to the modern knowledge and rich expository of science, technology, literature, medical sciences, philosophy and art. It has its share in the economic development and business exposure, in which India has excelled and Pakistan is pressing hard to reach the socio-economic pinnacle. The Anglo-Indian literature led the natives to creative ingenuity in English, hence Indo- Anglican literature came into existence, which initially was an explicit retaliation and repulsion to the act of colonization, but after independence, the literature produced in English in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh has claimed international interest and recognition. The creative impulse and ingenuity of the diasporas and the writers at home have added new branch of English literature to the bulk produced in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. In the wake of globalization, it has got fresh stimulus in international perspective, and the revolution of information technology has its own share and role. Thus, it provides edge to the people of these countries over the natives of even developed nations like Chinese, Japanese and Russian. Presently, the children of elite upper class, upper middle class are enrolled in the English medium institutes, which have its own pros and cons. The cultural dislocation, alienation would cast its grey repercussion in future. The vernaculars have received fatal blow in the aftermath of English language dominance, these vernaculars have been heavily Anglicized. The amalgamation of English words in the vernacular articulation is the most common phenomenon even at the level of mediocre layman.

It will be befitting to wind up the argument that the story of English language in the Indian subcontinent is the matter of loss and gain: it has given much to the region, at the same it has taken very much from it. However, it is an obvious fact that with the shift in the medium of instruction from the classical or local vernaculars and “engraftment of contents” to English as a medium of instruction, the classical languages and the local vernaculars of the subcontinent were adversely affected. If the practice of engraftment of the western knowledge and science into the classical languages and local vernaculars had been continued, presently these languages would have been infinitely rich in semantics, contents and concepts to keep pace with the modern era of science and technology. However, the upcoming time will account the ultimate impact of this innovation in the region.

Reference:

• Adams, N.L. and Adams, D.M. “An Examination of Some of the Forces Affecting English Educational Policies in India: 1780–1850.” History of Education Quarterly 11, 1971, pp. 157-173.

• Annika Hohenthal. “English in India: Loyalty and Attitude”. In Language in India, vol.3, 2003, http://www.languageinindia.com/ may2003/annika.html, visited on June 13, 2013.

• Ashton, S.R. Colonization in India. The British Library: London. 1988.

• Bailey, Richard W. Images of English. A Cultural History of the Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

• Benson, J. The British debate over the medium of instruction in Indian education,1823–64. Journal of Educational Administration and History 4, 1972, pp. 1-12.

• Brian, Mac Arthur. The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches ed. Penguin Books. (1996).

• Carson, P. “Golden Casket or Pebbles and Trash? J.S. Mill and the Anglicist/Orientalist Controversy.” In M.I. Moir, D.M. Peers and L. Zastoupil (eds) J.S. Mill’s Encounter with India. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999, pp. 149-172.

• Chatterji, Reena. Impact of Raja Rammohan Roy on Education in India. Delhi: S. Chand, 1983.

• Cheshire, Jenny. English around the World. Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

• Clive, J. Macaulay: The Shaping of the Historian. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973.

• Das, Krishanchand and Patra, Deepchand. Studies in English Literature. New Delhi: Commonwealth Publishers, 2009.

• David, S.M. ‘Save the Heathens from Themselves’: The evolution of the educational policy of the East India Company till 1854. Indian Church History Review 18. Education Commission (1883) Report of the Indian Education Commission. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. 1984, pp. 19–29.

• Dumont, Louis. Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and its Implication. University of Chicago Press, 1980.

• Fisher, T. “Memoir on Education of Indians. Bengal Past and Present 18. 1919, pp.73-156.

• Frykenberg, R.E. “Modern Education in South India, 1784–1854: Its Roots and its Role as a Vehicle of Integration under Company Raj”, American Historical Review 91, 1986, pp. 37–65.

• Frykenberg, R.E. “The myth of English as a ‘colonialist’ imposition upon India: A reappraisal with special reference to south India”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 2, 1988, pp. 305– 315.

• Ghosh, S.C. “Bentinck, Macaulay and the Introduction of English Education in India.” History of Education 24, 1995, pp.17–24.

• Hilliker, J.F. “Charles Edward Trevelyan as an Educational Reformer in India 1827–1838.” Canadian Journal of History 9, 1974, pp. 275-291.

• James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 1994, pp.221-231.

• Kachru, Braj B. "The power and politics of English." In World Englishes, Vol. 5, No. 2/3, 1986b, pp.121-140.

• Kachru, Braj B. "World Englishes and English-using communities." In Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 17, 1997, pp. 66-87.

• Kachru, Braj B. The Alchemy of English. The Spread, Functions and Models of Non-Native Englishes. Oxford: Pergamon Press Ltd, 1986a.

• Kachru, Braj B. The Indianization of English. The English Language in India. Oxford: OUP. 1983.

• Kirshnaswamy, N. and Lalitah Krishnaswamy. The Story of English in India. New Delhi: Foundation Books, 2006.

• Kopf, D. British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California, 1969.

• Majumdar, R.C. “The Hindu College”, Journal of the Asiatic Society 11, 1955, pp.39–51.

• Mayhew, A. The Education of India. London: Faber and Gwyer, 1926.

• Moss, Peter. Oxford History for Pakistan, a revised and expanded version of Oxford History Project Book Three; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. • Mubarak Ali. “Different Strokes”, published in The Sunday, Magazine: The daily Dawn, Karachi, Oct.5, 2008.

• Mukherjee, “A. Decline of Oriental Education (Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian) in Bengal from 1835 to the End of the Century: Some Social Aspects.” Quarterly Review of Historical Studies 28, 1989, pp. 19–28.

• Mwiria, K. “Education for Subordination: African Education in Colonial Kenya.” History of Education 20, 1991, pp.261-273.

• NEB: The New Encyclopedia Britannica (Macropaedia). 15th ed., vol.9. Chicago: Helen Hemingway Benton, 1974.

• Pachori, S.S. “The language policy of the East India Company and the Asiatic Society of Bengal.” Language Problems and Language Planning 14, 1990, pp. 104–118.

• Pennycook, Alastair. The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. Harlow: Longman Group Ltd, 1994.

• Philips, C.H. (Eds.) The Correspondence of Lord William Bentinck, Governor-General of India, 1828–1835: Volume II. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

• Rahim, S.A. Language as Power Apparatus: Observations on English and Cultural Policy in Nineteenth-century India. World Englishes 5, 1986, pp. 231–239.

• Rosselli, J. Lord William Bentinck: The Making of a Liberal Imperialist 1774–1839. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974.

• Spear, Percival. “Bentinck and education”, Cambridge Historical Journal 6, 1938, pp. 78–101.

• Vohra, Ranbir. The Making of India: A Historical Survey. Second Edition. New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. 2001.

• Washbrook, D.A. “India, 1818–1860: The two faces of colonialism.” In A. Porter (ed.) The Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 395-421.

• Whitehead, C. “The Advisory Committee on Education in the [British] Colonies 1924–1961.” Paedagogica Historica 27, 1991, pp.385-421.

• Zastoupil, L. and Moir, M. (Eds.). The Great Indian Education Debate: Documents Relating to the Orientalist-Anglicist Controversy, 1781– 1843. Richmond: Curzon Press, 1999.

• Zastoupil, L. John Stuart Mill and India. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994.

FREDA BEDI CONT'D (#4)

Re: FREDA BEDI CONT'D (#4)

Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/28/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worshipfu ... per_Makers

Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers

Motto: Verbum Domini Manet in Aeternum

Location: Stationers' Hall, London

Date of formation: 1403

Company association: Printing and publishing

Order of precedence: 47th

Master of company: Paul Wilson

Website stationers.org

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (until 1937 the Worshipful Company of Stationers), usually known as the Stationers' Company, is one of the livery companies of the City of London.[1] The Stationers' Company was formed in 1403; it received a Royal Charter in 1557.[2] It held a monopoly over the publishing industry and was officially responsible for setting and enforcing regulations until the enactment of the Statute of Anne, also known as the Copyright Act of 1710.[3] Once the company received its charter, "the company's role was to regulate and discipline the industry, define proper conduct and maintain its own corporate privileges."[4]

The company members, including master, wardens, assistants, liverymen, freemen and apprentices are mostly involved with the modern visual and graphic communications industries that have evolved from the company's original trades. These include printing, paper-making, packaging, office products, engineering, advertising, design, photography, film and video production, publishing of books, newspapers and periodicals and digital media. The company's principal purpose nowadays is to provide an independent forum where its members can advance the interests (strategic, educational, training and charitable) of the industries associated with the company.[5]

History

In 1403, the Corporation of London approved the formation of a guild of stationers. At this time, the occupations considered stationers for the purposes of the guild were text writers, limners (illuminators), bookbinders or booksellers who worked at a fixed location (stationarius) beside the walls of St Paul's Cathedral.[6] Booksellers sold manuscript books, or copies thereof produced by their respective firms for retail; they also sold writing materials. Illuminators illustrated and decorated manuscripts.

Printing gradually displaced manuscript production so that, by the time the guild received a royal charter of incorporation on 4 May 1557, it had in effect become a printers' guild. In 1559, it became the 47th in city livery company precedence. At the time, it was based at Peter's College, which it bought from St Paul's Cathedral.[7] During the Tudor and Stuart periods, the Stationers were legally empowered to seize "offending books" that violated the standards of content set down by the Church and state; its officers could bring "offenders" before ecclesiastical authorities, usually the Bishop of London or the Archbishop of Canterbury, depending on the severity of the transgression.[8] Thus the Stationers played an important role in the culture of England as it evolved through the intensely turbulent decades of the Protestant Reformation and toward the English Civil War.

The Stationers' Charter, which codified its monopoly on book production, ensured that once a member had asserted ownership of a text or "copy" by having it approved by the company, no other member was entitled to publish it, that is, no one else had the "right to copy" it. This is the origin of the term "copyright". However, this original "right to copy" in England was different from the modern conception of copyright. The stationers' "copy right" was a protection granted to the printers of a book; "copyright" introduced with the Statute of Anne, or the Copyright Act of 1710, was a right granted to the author(s) of a book based on statutory law.[9]

Members of the company could, and mostly did, document their ownership of copyright in a work by entering it in the "entry book of copies" or the Stationers' Company Register.[10] The Register of the Stationers' Company thus became one of the most essential documentary records in the later study of English Renaissance theatre.[11] (In 1606 the Master of the Revels, who was responsible until this time for licensing plays for performance, acquired some overlapping authority over licensing them for publication as well; but the Stationers' Register remained a crucial and authoritative source of information after that date too.) Enforcement of such rules was always a challenge, in this area as in other aspects of the Tudor/Stuart regime. Works were often printed surreptitiously and illegally, and this would remain a subject of interest to both the Company and the government into the modern period.

In 1603, the Stationers formed the English Stock, a joint stock publishing company funded by shares held by members of the company.[12] This profitable venture gave the Company a monopoly on printing certain types of works, including almanacs, prayer-books, and primers, some of the best-selling works of the day. By buying and holding shares in the English Stock (which were limited in number), members of the company received a nearly guaranteed return each year. The English Stock at times employed out-of-work printers, and disbursed some of the profit to the poor and to those reliant on the Company's pensions. When a printer or bookseller who held a share died, it might often pass to another relation, most often his widow.[13]

Stationers' Hall, London (2013 photo)

In 1606, the company bought Abergavenny House in Ave Maria Lane and moved out of Peter's College.[14] The new hall burnt down in the Great Fire of 1666, along with most of its contents, including a great number of books. The Company's clerk, George Tokefeild, is said to have removed a great number of the Company's records to his home in the suburbs—without this act, much of the Company's history before 1666 would have been lost.[15] It was rebuilt by 1674, and its present interior is much as it was when it reopened. The Court Room was added in 1748, and in 1800 the external façade was remodelled to its present form.[16]

In 1695, the monopoly power of the Stationers' Company was diminished by the lapsing of their monopoly on printing, allowing presses to operate more freely outside of London than they had previously. This blow was compounded when in 1710 Parliament passed the Copyright Act 1709, the first such act to establish copyright as the purview of authors, not printers or publishers.[17]

In 1861, the company established the Stationers' Company's School at Bolt Court, Fleet Street for the education of sons of members of the Company. In 1894, the school moved to Hornsey in north London, eventually closing nearly a century later in 1983.

Registration under the Copyright Act 1911 ended in December 1923; the company then established a voluntary register in which copyrights could be recorded to provide printed proof of ownership in case of disputes.

In 1937, a royal charter amalgamated the Stationers' Company and the Newspaper Makers' Company, which had been founded six years earlier (and whose members were predominant in Fleet Street), into the company of the present name.

In March 2012, the company established the "Young Stationers", to provide a forum for young people (under the age of 40) within the company and the civic City of London more broadly. This led to the establishment of the Young Stationers' Prize in 2014, which recognises outstanding achievements within the company's trades. Prize winners have included novelist Angela Clarke, journalist Katie Glass, and professor of journalism Dr Shane Tilton.

The company's motto is Verbum Domini manet in aeternum, Latin for "The Word of the Lord endures forever;" which appears on their heraldic charge.[18]

In November 2020 Stationers' Hall the home of the Stationers' Company were granted approval to redevelop their Grade 1 listed building to bring modern day conference facilities, air-cooling and step free access to its historic rooms. It reopened in July 2022 for live events, weddings, and filming.

Trades

The modern Stationers' Company represents the "content and communications" industries within the City of London Liveries. This includes the following trades and specialisms:

• Archiving (including librarian, curators, and book conservation)

• Bookselling and distribution

• Communications (including advertising, marketing, and PR)

• Digital media and software

• Newspapers and broadcasting

• Office products and supplies

• Packaging

• Paper

• Print machinery

• Printing

• Publishing (including digital publishing and design)

• Writing (including journalism, broadcasting, and authorship)

Hall

Stationers' Hall is at Ave Maria Lane near Ludgate Hill. The site of the present hall was formerly the site of Abergavenny House, which was purchased by the Stationers in 1606 for £3,500, but destroyed in the Great Fire of London, 1666.[19] The current building and hall date from circa 1670. The hall was remodelled in 1800 by the architect Robert Mylne and, on 4 January 1950, it was designated a Grade I listed building.[20][21]

Stationers' Hall hosts the Shine School Media Awards, where students compete in the creation of websites and magazines.

Stationers' Hall

Main Hall

Caxton window

The Stock Room

The Court Room

Notable liverymen

• Edward Allde

• John Cleave

• Thomas Cotes

• George Eld

• Edmund Evans

• George Faulkner

• Richard Field

• Augustine Matthews

• George Mudie (Owenite)

• Rupert Murdoch

• Thomas Cautley Newby

• Nicholas Okes

• Peter Short

• William Stansby

• John Trundle

• Sir Christopher Meyer

• William Hague

Court

Below are lists of officials who either sat on the Stationer's Company Court of Assistants, or who worked for the Company in another official capacity (Beadle, Treasurer, and Clerk) from the time the Company was first granted a charter in 1556 to the present day. As with most London livery companies, the Master of the Company was elected yearly, along with the Wardens. For the Stationers, this election day always took place in late June, the day before St. Peter's Day (June 29). Thus, a Master's term would run effectively from July to July. The dates below reflect the year a Master was elected and began a term of service. Upper and Under Wardens were elected at the same time, while Renter Wardens (those two wardens charged with collecting dues from members of the Company annually) were chosen for the following year in March, on or around Lady Day. The roles of Beadle and Clerk were likewise elected positions, filled whenever they came open, but were often held by the same members for years or even decades. The Treasurer of the Company/English Stock was elected annually in March along with the Stockeepers, and again, was often held by the same person for years.

The master oversaw Company "courts", meetings of the Assistants and sometimes the Livery and wider membership where Company business was discussed and resolved. These courts were usually held monthly but could be held more or less frequently. Although official company positions were historically always held by men until the twentieth century, women have always participated meaningfully in the life of the Company, at certain times even holding a controlling interest in the Company's joint stock venture, known as the English Stock.[22][23][24]

The first woman elected master was Helen Esmonde, who held the position in 2015.[25]

1555–1599

1600–1699

1700–1799

1800–1899

1900–1999

2000–present

Young Stationers' Prize

Young Stationers' Prize with engraved winners as of 2018

The "Young Stationers' Prize" is an annual prize awarded by the Young Stationers' Committee to a young person under 40 years of age who has distinguished themself within the company's trades. Launched in 2014, the prize is a pewter plate (donated by the Worshipful Company of Pewterers) onto which each winner's name is engraved.

List of Young Stationers' Prize winners

As of December 2019 there have been seven winners of the Young Stationers' Prize: Katie Glass, journalist, 2014;[38][39] Angela Clarke, novelist, playwright, and columnist, 2015;[40][41] Ella Kahn and Bryony Woods, founders of Diamond Kahn & Woods Literary Agency (awarded jointly), 2016;[42] Ian Buckley, managing director of Prima Software, 2017;[43] Shane Tilton, academic and professor of multimedia journalism, 2018;[44] Amy Hutchinson, CEO of the BOSS Federation, 2019.[45]

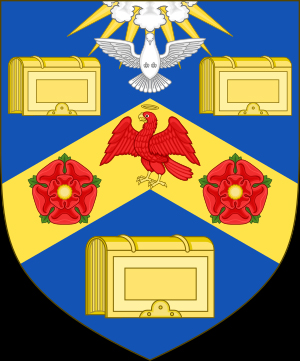

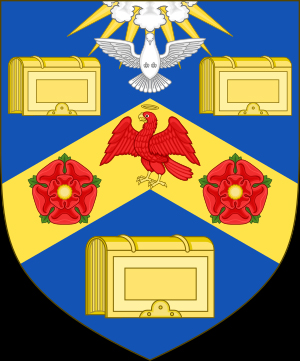

Arms

Coat of arms of Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers hide

Crest: On a wreath of the colours, An eagle, wings expanded, with a diadem above its head, perched on a book fessewise, all Or.

Escutcheon

Azure, on a chevron between three books with clasps, all Or an eagle volant gules with a nimbus Or, between two roses gules leaved vert, in chief issuing out of a cloud proper radiated Or a Holy Spirit, wings displayed, argent with a nimbus Or.

Supporters

On either side an angel proper, vested argent, mantled azure, winged and blowing a trumpet Or.

Motto

'Verbum Dei manet in aetemum'[46]

See also

• Authorized King James Version

• Eyre & Spottiswoode

• Fleet Street

• Printing patent

References

1. "Livery Committee: The Worshipful Company of Stationers & Newspaper Makers". Retrieved 25 January 2024.

2. Blagden, Cyprian. The Stationers' Company: A History, 1403–1959. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1960, p.19

3. Raven, James (2007). The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade 1450–1850. Yale University Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780300181630.

4. Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 61.

5. "About Us". The Stationer's Company.

6. Patterson, Lyman Ray (1968). Copyright in Historical Perspective. Vanderbilt University Press.

7. Blagden, Cyprian. "The Property". The Stationers' Company: a History, 1403–1959. p. 206, n2. On November 24, 1548, John and Richard Keyme, gentlemen of Lewes, paid £1,154 15 shillings into the Court of Augmentations and obtained possession, along with other property, of 'the site, house and mansion commonly called Peter College' (Cal. Patent Rolls Ed. VI, i, 362–363). Four years later, William Sparke, a Merchant Taylor, conveyed the property to the executors of Matthew Wotton, clerk, but retained the right to reclaim it on payment of £340; this figure may approximate to that paid by the Stationers two years later still (Hustings Roll 246, 63). For a short period before 1553 William Seres used the building for a printing house.

8. Loades, D. M. (1974). "The Theory and Practice of Censorship in Sixteenth-Century England". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (24): 141–157. doi:10.2307/3678936.

9. Gadd, Ian (2016). "The Stationers' Company in England before 1710". In Alexander, I.; Gómez-Arostegui, H.T. (eds.). Research handbook on the history of copyright law. Cheltenham: Elgar.

10. Arber, Edward, ed. (1875–1877). Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers of London, 1554–1640 A.D.

11. Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1923). The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 160–177, 186–191.

12. Blagden, Cyprian (1957). "English Stock of the Stationers' Company in the Time of the Stuarts". The Library (12).

13. Turner, Michael (2009). "Personnel within the London Book Trades: Evidence from the Stationers' Company". Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

14. See Blagden, "The Property", in The Stationers' Company: a History, especially pages 212–215.

15. Blagden, "The Great Fire and the Rebuilding", in The Stationer's Company: a History, p.215. The Company remembers Tokefeild's contribution today in the name of its Archives Center.

16. Blagden, The Stationers' Company: a History

17. See the Statute of Anne. The Company maintained a copyright registry untl 1923, after which registrations became voluntary.

18. "Stationer's Company". British Armorial Bindings Database. University of Toronto. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

19. "Official website". Stationers Livery Company. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

20. Historic England. "Stationers' Hall (Grade I) (1064742)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

21. Blagden, Cyprian (1977) [1960]. "The Property". The Stationers' Company: A History, 1403–1959. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804709354.

22. Turner, Michael (2009). "Personnel within the London Book Trades: Evidence from the Stationers' Company". The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain 5: 1695–1830. p. 331. There were occasions in the eighteenth century when the majority of the Assistants' shares were in the hands of surviving widows rather than active Assistants.

23. Smith, Helen (2012). Grossly Material Things: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England. Oxford University Press.

24. McDowell, Paula (1998). The Women of Grub Street: Press, Politics, and Gender in the London Literary Marketplace 1678–1730. Oxford University Press.

25. "Master breaks centuries old barrier". Print Business. 27 July 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

26. Turner, Michael. "London Booktrades Database". London Booktrades Database. Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

27. Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (4 October 2021). "Masters of the Company" (Document). Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

28. Turner, Michael. "London Booktrades Database". London Booktrades Database. Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

29. Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (4 October 2021). "Masters of the Company" (Document). Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

30. Turner, Michael. "London Booktrades Database". London Booktrades Database. Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

31. Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (4 October 2021). "Masters of the Company" (Document). Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

32. Turner, Michael. "London Booktrades Database". London Booktrades Database. Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

33. Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (4 October 2021). "Masters of the Company" (Document). Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

34. Turner, Michael. "London Booktrades Database". London Booktrades Database. Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

35. Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (4 October 2021). "Masters of the Company" (Document). Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

36. Turner, Michael. "London Booktrades Database". London Booktrades Database. Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

37. Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (4 October 2021). "Masters of the Company" (Document). Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

38. "Announcement of the Young Stationers' Prize winner". InPublishing. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

39. "Profile: Katie Glass". The Times & Sunday Times. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

40. Crockett, Sophie (4 August 2015). "St Albans playwright, Angela Clarke, scoops award". The Herts Advertiser. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

41. Cheesman, Neil (24 July 2015). "Debut playwright Angela Clarke wins The Young Stationers' Prize 2015". LondonTheatre1. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

42. "Former SYP committee members win Young Stationers' Prize". Society of Young Publishers. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

43. Goldbart, Max (28 July 2017). "Buckley scoops Young Stationers' prize". Printweek. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

44. "Dr Shane Tilton wins Young Stationers' Prize". British Printing Industries Federation. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

45. Handley, Rhys (12 July 2019). "New Boss chief wins Young Stationers' prize". Printweek. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

46. "Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

Further reading

• Arber, Edward, ed. (1875–1877), Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers of London, 1554–1640 A.D.

• v.2, 1571–1595

• v.3, 1595–1620

• v.4, 1620–1640

• v.5, index

• Bell, Maureen (1996). "Women in the English Book Trades 1557–1700". Leipziger Jahrbuch zur Buchgeschichte. 6: 13–45.

• Blagden, Cyprian (1957). "Accounts of the Wardens of the Stationers' Company". Studies in Bibliography. 9: 69–93. JSTOR 40371196.

• Blagden, Cyprian (1957). "English Stock of the Stationers' Company in the Time of the Stuarts". The Library. 12.

• Blagden, Cyprian (1958). "Stationers' Company in the Civil War Period". The Library. 13.

• Blagden, Cyprian (1959). "Stationers' Company in the Eighteenth Century". Guildhall Miscellany. ISSN 0072-8985.

• Blagden, Cyprian (1960). The Stationers' Company: A History, 1403–1959. London: Allen & Unwin. OCLC 459559508.

• Blayney, Peter (2003), Stationers' Company before the Charter, 1403–1557, London: Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers, OCLC 52634009

• Blayney, Peter W. M. (2013). The Stationers' Company and the Printers of London: 1501–1557. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

• Eyre, G. E. B.; Rivington, C. R., eds. (1913–1914), Transcript of the Registers of the worshipful Company of Stationers, from 1640–1708 A.D. + v.2–3

• Ferdinand, C. Y. (1992). "Towards a Demography of the Stationers' Company, 1601–1700". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 21. ISSN 0079-5321.

• Gadd, Ian; Wallis, Patrick (2002). Guilds, Society and Economy in London, 1450–1800. Centre for Metropolitan History in association with Guildhall Library, London. ISBN 9781871348651.

• Gadd, Ian (2016). "The Stationers' Company in England before 1710". In Alexander, I.; Gómez-Arostegui, H.T. (eds.). Research handbook on the history of copyright law. Research handbooks in intellectual property. Cheltenham: Elgar. pp. 81–95. ISBN 9781783472390.

• Gadd, Ian (2013). "The press and the London book trade". In Gadd, Ian (ed.). History of Oxford University Press, Volume 1: Beginnings to 1780. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 569–600. ISBN 9780199557318.

• Gadd, Ian; Wallis, Patrick (2008). "Reaching beyond the City Wall: London guilds and national regulation, 1500–1700". In Epstein, S.; Prak, M. (eds.). Guilds, innovation, and the European economy 1400–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521887175.

• Gadd, Ian (2021). "The Stationers' Company, 1403–1775: London's book trade guild". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature.

• Greg, W. W.; Boswell, E. (1930). Records of the Court of the Stationers' Company, 1576 to 1602 – from Register B.

• Greg, W. W. (1928). The Decrees and Ordinances of the Stationers' Company, 1576–1602.

• "Government Control of the Printing Press: Star Chamber Censorship Ordinances (1566, 1586) and Philip Stubbs' Comments on Censorship (1593)". Voices of Shakespeare's England: Contemporary Accounts of Elizabethan Daily Life. 2010.

• Jackson, W. A. (1957). Records of the Court of the Stationers' Company, 1602 to 1640.

• Knight, Charles, ed. (1844), "Stationers' Company", London, vol. 6, London: C. Knight & Co.

• McDowell, Paula (1998). The Women of Grub Street: Press, Politics, and Gender in the London Literary Marketplace 1678–1730. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198184492.

• McKenzie, D. F. (ed.), Stationers' Company Apprentices, 1605–1800 in three volumes: 1605–1640, 1641–1700 and 1701–1800. (Charlottesville: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 1961; Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1974 and 1978)

• Mendle, Michael (1995). "De Facto Freedom De Facto Authority: Press and Parliament 1640–1643". The Historical Journal: 307–32.

• Myers, Robin (1985), Myers, Robin; Harris, Michael (eds.), "The Financial Records of the Stationers' Company, 1605–1811", Economics of the British Booktrade 1605–1939, Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey, ISBN 0859641694

• Myers, Robin (1990). The Stationers' Company Archive: An Account of the Records, 1554–1984. Winchester: St Paul's Bibliographies.

• Myers, Robin; Harris, Michael, eds. (1997). Stationers' Company and the Book Trade 1550–1990. Winchester: St Paul's Bibliographies. ISBN 9781873040331.

• Myers, Robin, ed. (2001). Stationers' Company: a history of the later years 1800–2000. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 9781860771408.

• Nichols, John Gough (1861), Historical notices of the worshipful Company of stationers of London, OCLC 5386736, OL 6639628M

• Pollard, Graham (1937). "Company of Stationers before 1557". The Library. 18. ISSN 1744-8581.

• Pollard, Graham (1937). "Early Constitution of the Stationers' Company". The Library. 18.

• Raven, James (2007). The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade 1450–1850. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300181630.

• Rivington, Charles Robert (1883), Records of the Worshipful Company of Stationers, Nichols and Sons, OCLC 19943126

• Siebert, Fred S. (1936). "Regulation of the Press in the Seventeenth Century: Excerpts from the Records of the Court of the Stationers' Company". Journalism Quarterly. 13 (4): 381–393. doi:10.1177/107769903601300402. S2CID 159460546.

• Sketch of the History and Privileges of the Company of Stationers. London Stationers' Hall. 1871.

• Smith, Helen (2012). Grossly Material Things: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199651580.

• "Stationers' Hall", Handbook to London as It Is, London: J. Murray, 1879

• "Stationers' Hall", London and Its Environs (17th ed.), Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1915, hdl:2027/mdp.39015019440851

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

• The Stationers' and Newspaper Makers' Company

• Events Venue Website

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/28/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worshipfu ... per_Makers

[Mountstuart Elphinstone] There appear to me to be only three lines of conduct which we can possibly adopt. 1st, To check the diffusion of knowledge and the introduction of printing so as to keep the Natives in their present state and confine the effects of the Press as hitherto to the Europeans. 2nd, To allow perfect freedom to Native Press and to offer no resistance to the natural tendency of such freedom to dispose the Native to attempts at establishing a national Government. 3rd, To promote learning and to encourage printing, but to keep the Press under the same degree of restraint which was maintained in England for more than two centuries after the invention of printing and which is still enforced in all countries where the Government does not rest on a popular basis. The first of these plans would be criminal if it were practicable. The second would only lead to the premature removal of the British Government, without a chance of its being succeeded by a better; the third alone appears to me to offer any prospect of improvement and rational liberty to the Natives. Under it we might safely do our duty in communicating to them all the sciences of Europe; and at some distant period the two nations might be sufficiently on a footing to determine the relation they were thenceforth to bear to one another. At that stage the people might be admitted to a share of the Government and then or at a later period the freedom of the Press might be permitted without control.

-- The Printing Press in India: It's Beginnings and Early Development Being a Quatercentenary Commemoration Study of the Advent of Printing in India (In 1556), by Anant Kakba Priolkar, Director, Marathi Samshodhana Mandala, Bombay

Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers

Motto: Verbum Domini Manet in Aeternum

Location: Stationers' Hall, London

Date of formation: 1403

Company association: Printing and publishing

Order of precedence: 47th

Master of company: Paul Wilson

Website stationers.org

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (until 1937 the Worshipful Company of Stationers), usually known as the Stationers' Company, is one of the livery companies of the City of London.[1] The Stationers' Company was formed in 1403; it received a Royal Charter in 1557.[2] It held a monopoly over the publishing industry and was officially responsible for setting and enforcing regulations until the enactment of the Statute of Anne, also known as the Copyright Act of 1710.[3] Once the company received its charter, "the company's role was to regulate and discipline the industry, define proper conduct and maintain its own corporate privileges."[4]

The company members, including master, wardens, assistants, liverymen, freemen and apprentices are mostly involved with the modern visual and graphic communications industries that have evolved from the company's original trades. These include printing, paper-making, packaging, office products, engineering, advertising, design, photography, film and video production, publishing of books, newspapers and periodicals and digital media. The company's principal purpose nowadays is to provide an independent forum where its members can advance the interests (strategic, educational, training and charitable) of the industries associated with the company.[5]

History

In 1403, the Corporation of London approved the formation of a guild of stationers. At this time, the occupations considered stationers for the purposes of the guild were text writers, limners (illuminators), bookbinders or booksellers who worked at a fixed location (stationarius) beside the walls of St Paul's Cathedral.[6] Booksellers sold manuscript books, or copies thereof produced by their respective firms for retail; they also sold writing materials. Illuminators illustrated and decorated manuscripts.

Printing gradually displaced manuscript production so that, by the time the guild received a royal charter of incorporation on 4 May 1557, it had in effect become a printers' guild. In 1559, it became the 47th in city livery company precedence. At the time, it was based at Peter's College, which it bought from St Paul's Cathedral.[7] During the Tudor and Stuart periods, the Stationers were legally empowered to seize "offending books" that violated the standards of content set down by the Church and state; its officers could bring "offenders" before ecclesiastical authorities, usually the Bishop of London or the Archbishop of Canterbury, depending on the severity of the transgression.[8] Thus the Stationers played an important role in the culture of England as it evolved through the intensely turbulent decades of the Protestant Reformation and toward the English Civil War.

The Stationers' Charter, which codified its monopoly on book production, ensured that once a member had asserted ownership of a text or "copy" by having it approved by the company, no other member was entitled to publish it, that is, no one else had the "right to copy" it. This is the origin of the term "copyright". However, this original "right to copy" in England was different from the modern conception of copyright. The stationers' "copy right" was a protection granted to the printers of a book; "copyright" introduced with the Statute of Anne, or the Copyright Act of 1710, was a right granted to the author(s) of a book based on statutory law.[9]

Members of the company could, and mostly did, document their ownership of copyright in a work by entering it in the "entry book of copies" or the Stationers' Company Register.[10] The Register of the Stationers' Company thus became one of the most essential documentary records in the later study of English Renaissance theatre.[11] (In 1606 the Master of the Revels, who was responsible until this time for licensing plays for performance, acquired some overlapping authority over licensing them for publication as well; but the Stationers' Register remained a crucial and authoritative source of information after that date too.) Enforcement of such rules was always a challenge, in this area as in other aspects of the Tudor/Stuart regime. Works were often printed surreptitiously and illegally, and this would remain a subject of interest to both the Company and the government into the modern period.

In 1603, the Stationers formed the English Stock, a joint stock publishing company funded by shares held by members of the company.[12] This profitable venture gave the Company a monopoly on printing certain types of works, including almanacs, prayer-books, and primers, some of the best-selling works of the day. By buying and holding shares in the English Stock (which were limited in number), members of the company received a nearly guaranteed return each year. The English Stock at times employed out-of-work printers, and disbursed some of the profit to the poor and to those reliant on the Company's pensions. When a printer or bookseller who held a share died, it might often pass to another relation, most often his widow.[13]

Stationers' Hall, London (2013 photo)

In 1606, the company bought Abergavenny House in Ave Maria Lane and moved out of Peter's College.[14] The new hall burnt down in the Great Fire of 1666, along with most of its contents, including a great number of books. The Company's clerk, George Tokefeild, is said to have removed a great number of the Company's records to his home in the suburbs—without this act, much of the Company's history before 1666 would have been lost.[15] It was rebuilt by 1674, and its present interior is much as it was when it reopened. The Court Room was added in 1748, and in 1800 the external façade was remodelled to its present form.[16]

In 1695, the monopoly power of the Stationers' Company was diminished by the lapsing of their monopoly on printing, allowing presses to operate more freely outside of London than they had previously. This blow was compounded when in 1710 Parliament passed the Copyright Act 1709, the first such act to establish copyright as the purview of authors, not printers or publishers.[17]

In 1861, the company established the Stationers' Company's School at Bolt Court, Fleet Street for the education of sons of members of the Company. In 1894, the school moved to Hornsey in north London, eventually closing nearly a century later in 1983.

Registration under the Copyright Act 1911 ended in December 1923; the company then established a voluntary register in which copyrights could be recorded to provide printed proof of ownership in case of disputes.

In 1937, a royal charter amalgamated the Stationers' Company and the Newspaper Makers' Company, which had been founded six years earlier (and whose members were predominant in Fleet Street), into the company of the present name.

In March 2012, the company established the "Young Stationers", to provide a forum for young people (under the age of 40) within the company and the civic City of London more broadly. This led to the establishment of the Young Stationers' Prize in 2014, which recognises outstanding achievements within the company's trades. Prize winners have included novelist Angela Clarke, journalist Katie Glass, and professor of journalism Dr Shane Tilton.

The company's motto is Verbum Domini manet in aeternum, Latin for "The Word of the Lord endures forever;" which appears on their heraldic charge.[18]

In November 2020 Stationers' Hall the home of the Stationers' Company were granted approval to redevelop their Grade 1 listed building to bring modern day conference facilities, air-cooling and step free access to its historic rooms. It reopened in July 2022 for live events, weddings, and filming.

Trades

The modern Stationers' Company represents the "content and communications" industries within the City of London Liveries. This includes the following trades and specialisms:

• Archiving (including librarian, curators, and book conservation)

• Bookselling and distribution

• Communications (including advertising, marketing, and PR)

• Digital media and software

• Newspapers and broadcasting

• Office products and supplies

• Packaging

• Paper

• Print machinery

• Printing

• Publishing (including digital publishing and design)

• Writing (including journalism, broadcasting, and authorship)

Hall

Stationers' Hall is at Ave Maria Lane near Ludgate Hill. The site of the present hall was formerly the site of Abergavenny House, which was purchased by the Stationers in 1606 for £3,500, but destroyed in the Great Fire of London, 1666.[19] The current building and hall date from circa 1670. The hall was remodelled in 1800 by the architect Robert Mylne and, on 4 January 1950, it was designated a Grade I listed building.[20][21]

Stationers' Hall hosts the Shine School Media Awards, where students compete in the creation of websites and magazines.

Stationers' Hall

Main Hall

Caxton window

The Stock Room

The Court Room

Notable liverymen

• Edward Allde

• John Cleave

• Thomas Cotes

• George Eld

• Edmund Evans

• George Faulkner

• Richard Field

• Augustine Matthews

• George Mudie (Owenite)

• Rupert Murdoch

• Thomas Cautley Newby

• Nicholas Okes

• Peter Short

• William Stansby

• John Trundle

• Sir Christopher Meyer

• William Hague

Court

Below are lists of officials who either sat on the Stationer's Company Court of Assistants, or who worked for the Company in another official capacity (Beadle, Treasurer, and Clerk) from the time the Company was first granted a charter in 1556 to the present day. As with most London livery companies, the Master of the Company was elected yearly, along with the Wardens. For the Stationers, this election day always took place in late June, the day before St. Peter's Day (June 29). Thus, a Master's term would run effectively from July to July. The dates below reflect the year a Master was elected and began a term of service. Upper and Under Wardens were elected at the same time, while Renter Wardens (those two wardens charged with collecting dues from members of the Company annually) were chosen for the following year in March, on or around Lady Day. The roles of Beadle and Clerk were likewise elected positions, filled whenever they came open, but were often held by the same members for years or even decades. The Treasurer of the Company/English Stock was elected annually in March along with the Stockeepers, and again, was often held by the same person for years.

The master oversaw Company "courts", meetings of the Assistants and sometimes the Livery and wider membership where Company business was discussed and resolved. These courts were usually held monthly but could be held more or less frequently. Although official company positions were historically always held by men until the twentieth century, women have always participated meaningfully in the life of the Company, at certain times even holding a controlling interest in the Company's joint stock venture, known as the English Stock.[22][23][24]

The first woman elected master was Helen Esmonde, who held the position in 2015.[25]

1555–1599

Sixteenth Century Court Officials, 1556–1599[26][27]

Year elected / Master / Upper Warden / Under Warden / Renter Wardens / Clerk / Beadle / Treasurer

1555 Thomas Dockwray John Cawood Henry Cooke John Walley; Anthony Smythe Unknown Unknown Unknown

1556 Thomas Dockwray John Cawood Henry Cooke John Walley Unknown Unknown Unknown

1557 Thomas Dockwray John Cawood John Walley John Walley Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1558 Richard Waye John Jaques John Turke Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1559 Reginald (Reyner) Wolfe

Michael Loble Thomas Duxwell Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1560 Stephen Kevall Richard Jugge John Judson Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1561 John Cawood

William Seres Richard Tottell Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1562 John Cawood

Michael Loble Richard Harrison; John Judson [from February] Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1563 Richard Waye Richard Jugge Roger Ireland Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1564 Reginald (Reyner) Wolfe

John Walley John Day Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1565 Stephen Kevall William Seres James Gonneld Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1566 John Cawood

Richard Jugge John Day Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1567 Reginald (Reyner) Wolfe

Richard Tottell James Gonneld Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1568 Richard Jugge

Richard Tottell Roger Ireland Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1569 Richard Jugge

John Walley William Norton Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1570 William Seres

John Judson William Norton Unknown Unknown John Ffayreberne Unknown

1571 William Seres

John Day Humphrey Toy Unknown George Wapull Unknown Unknown

1572 Reginald (Reyner) Wolfe

James Gonneld Humphrey Toy Unknown George Wapull Unknown Unknown

1573 Richard Jugge

William Norton John Harrison [the elder] Unknown George Wapull Unknown Unknown

1574 Richard Jugge

Richard Tottell William Cooke Unknown George Wapull Unknown Unknown

1575 William Seres

John Day Thomas Marsh Unknown Richard Collins Unknown Unknown

1576 William Seres

James Gonneld Richard Watkins Unknown Richard Collins Unknown Unknown

1577 William Seres

William Norton Richard Watkins Unknown Richard Collins Unknown Unknown

1578 Richard Tottel

John Harrison [the elder] George Bishop Unknown Richard Collins Unknown Unknown

1579 James Gonneld John Harrison [the elder] George Bishop Unknown Richard Collins Unknown Unknown

1580 John Day

Richard Watkins Francis Coldock Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1581 William Norton Thomas Marsh Garrat Dewce Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1582 James Gonneld Christopher Barker Francis Coldock Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1583 John Harrison [the elder] Richard Watkins Ralph Newbery Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1584 Richard Tottel

George Bishop Ralph Newbery Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1585 James Gonneld Christopher Barker Henry Conway Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1586 William Norton George Bishop Henry Denham

Unknown Richard Collins Timothy Rider Unknown

1587 John Judson Francis Coldock Henry Middleton; Henry Conway [from September] Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1588 John Harrison [the elder] Francis Coldock Henry Denham Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1589 Richard Watkins Ralph Newbery Gabriel Cawood Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1590 George Bishop Ralph Newbery Gabriel Cawood Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1591 Francis Coldock Henry Conway George Allen Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1592 George Bishop Henry Conway Thomas Stirrop Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1593 William Norton [succeeded by George Bishop] Gabriel Cawood Thomas Woodcock; Thomas Stirrop [from April] Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1593 George Bishop [succeeds William Norton in December] Gabriel Cawood Thomas Woodcock; Thomas Stirrop [from April] Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1594 Richard Watkins Gabriel Cawood Isaac Binge Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1595 Francis Coldock Isaac Binge Thomas Dawson Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1596 John Harrison [the elder] Thomas Stirrop Thomas Dawson Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1597 Gabriel Cawood Thomas Stirrop Thomas Man Unknown Richard Collins John Wolfe Unknown

1598 Ralph Newbery Isaac Binge William Ponsonby Unknown Richard Collins Toby Cooke Unknown

1599 Gabriel Cawood Thomas Man John Windet Unknown Richard Collins Toby Cooke Unknown

1600–1699

Seventeenth Century Court Officials, 1600–1699[28][29]

Year elected /Master /Upper Warden /Under Warden /Senior Renter Warden /Junior Renter Warden Clerk / Beadle / Treasurer

1600 George Bishop Thomas Dawson Richard White Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Unknown

1601 Ralph Newbery Robert Barker Gregory Seton Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Unknown

1602 George Bishop Thomas Man Simon Waterson Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Unknown

1603 Isaac Binge Thomas Dawson Humphrey Hooper Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Unknown

1604 Thomas Man John Norton William Leake Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Unknown

1605 Robert Barker

John Norton Richard Feild Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Nathaniel Butter

1606 Robert Barker

Edward White William Leake Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy William Cotton

1607 John Norton Gregory Seton John Standish William Newton Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy William Cotton

1608 George Bishop Humphrey Hooper Humphrey Lownes Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy William Cotton

1609 Thomas Dawson Simon Waterson John Standish Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Edmund Weaver

1610 Thomas Man William Leake Thomas Adams Anthony Gilman Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Edmund Weaver

1611 John Norton Richard Feild Humphrey Lownes Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Edmund Weaver

1612 John Norton Humphrey Hooper John Harrison [the younger] Unknown Unknown Richard Collins John Hardy Edmund Weaver

1613 Bonham Norton

Richard Field Richard Ockould Unknown Unknown Thomas Mountfort Thomas Bushell Edmund Weaver

1614 Thomas Man William Leake Thomas Adams Felix Kingston Unknown Thomas Mountfort Thomas Bushell Edmund Weaver

1615 Thomas Dawson Humphrey Lownes, senior George Swinhowe Unknown Unknown Thomas Mountfort Thomas Bushell Edmund Weaver

1616 Thomas Man Thomas Adams Matthew Lownes Matthew Law Unknown Thomas Mountfort Thomas Bushell Edmund Weaver

1617 Simon Waterson Humphrey Lownes, senior George Swinhowe Robert Bolton Unknown Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1618 William Leake Thomas Adams Anthony Gilman Leonard Kempe Unknown Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1619 Richard Field

George Swinhowe John Jaggard Thomas Purfoote John Harrison Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1620 Humphrey Lownes Matthew Lownes George Cole John Harrison John Jaggard Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1621 Simon Waterson George Swinhowe Clement Knight Richard Tombes Unknown Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1622 Richard Field Anthony Gilman Thomas Pavier Richard Tombes John Browne Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1623 George Swinhowe George Cole John Bill John Browne Unknown Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1624 Humphrey Lownes Matthew Lownes Henry Cooke Unknown Unknown Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1625 George Swinhowe Anthony Gilman Adam Islip William Aspley Roger Jackson Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1626 Bonham Norton

Clement Knight Felix Kingston John Rothwell Henry Fetherstone Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1627 George Cole Clement Knight Edmund Weaver Henry Featherstone Nathaniel Butter Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1628 George Cole Adam Islip Edmund Weaver Unknown Unknown Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1629 Bonham Norton

John Bill Thomas Purfoote John Busby Emanuel Exoll Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1630 George Swinhowe Felix Kingston John Harrison Emanuel Exoll Thomas Downes Thomas Mountfort Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1631 George Cole Adam Islip John Smethwick Thomas Downes Richard Moore Henry Walley Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1632 George Cole Edmund Weaver William Aspley John Beale Richard Higganbotham Henry Walley Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1633 Adam Islip Edmund Weaver William Aspley John Hoth John Parker Henry Walley Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1634 Adam Islip Thomas Purfoote John Rothwell John Parker Francis Constable Henry Walley Richard Badger Edmund Weaver

1635 Felix Kingston John Smethwick Henry Featherstone Richard Whitaker George Latham Henry Walley John Badger Edmund Weaver

1636 Felix Kingston John Harrison Thomas Downes George Latham Jonas Wellings Henry Walley John Badger Edmund Weaver

1637 Edmund Weaver, died June 1638 William Aspley Nicholas Bourne Jonas Wellings Ephraim Dawson Henry Walley John Badger Edmund Weaver