Jawaharlal Nehru

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/26/20

In 1885, on retiring from the civil service, Hume summoned the first meeting of the Indian National Congress, in the hope of winning a greater role for Indians in administration under the British Crown. Over time, under Gandhi and Nehru, the Congress became the main propellant of independence, and in India today Hume's role as forerunner is still remembered and acknowledged. (The thirteen-year-old Nehru was, in fact, initiated into the Theosophical Society by its third leader, Annie Besant, and the "thrilled" youngster later saw "old Colonel Olcott with his fine beard.")

-- Mystical Imperialism, Excerpt from "Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia", by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac

[/quote]Contemporary India on occasion published keynote nationalist texts, such as Nehru's addresses to annual sessions of the Indian National Congress, but most of its content was specially written....

When Jawaharlal Nehru, in the months leading up to India's independence, sent a note to Freda Bedi, the address was wonderfully concise: The Huts, Model Town, Lahore....

The Indian Civil Liberties Union was established by the Congress's Jawaharlal Nehru in 1936 -- two years after the National Council for Civil Liberties was established in Britain, harnessing radical, communist and pacifist concerns about illiberalism and an intolerance towards political dissent. Freda was diligent in seeking out breaches of civil liberties and became the most prominent activist in Punjab of a movement which she insisted was non-party and non-denominational 'welcoming all shades of opinion in its rank'. By the spring of 1937, Freda was on the national council of the Civil Liberties Union and in June she was the principal organiser and speaker at a widely reported civil liberties conference in Amritsar. The purpose of the Union, she explained, was 'to throw the spotlight of publicity on any encroachments of the legal rights of the people, and to consolidate public opinion so that we are in a position to demand redress from the authorities concerned. Its function is therefore, mainly as a propagandistic body.' So the aim was to work within the system more than to challenge it. She talked of the civil liberties movements already in place in Europe and America 'and we can count on their help and co-operation in this fight which has in reality no national boundaries, but is concerned with man and his relation to the state. We of the Colonial countries' -- she declared in an emphatic expression of her identification with India over England -- 'may be more in need of such organizations, but it is only a matter of degree because wherever there are rich and poor, wherever in fact Capitalism raises its head, the need is urgent.'

Once established as a speaker, the demands on Freda's time became relentless....

Before boarding the plane [February, 1947], Freda dropped a line to a friend asking for advice about what to do in London. Jawaharlal Nehru, who by the end of the year was to become the first prime minister of independent India, sent a brief reply to her at The Huts. 'I hope you will enjoy your visit to England after 14 years,' he wrote. 'You should certainly meet Krishna Menon, I cannot suggest what you might do there, but Krishna Menon will, no doubt, be able to do so.'...

Freda's visit had a charming codicil. A year later, her mother received a last minute invitation to meet India's new prime minister. 'Summoned to a reception at India House, London, to meet Jawaharlal Pandit Nehru, Mrs. F.N. Swan ... cooked a meal for four, prepared the next day's food and then found time to go out and buy herself a new dress and a new hat for the occasion before catching a train to London less than seven hours after receiving the invitation,' reported the Derby Daily Telegraph. Mrs Swan told the paper that her daughter was 'well known to Pandit Nehru' and she said her proudest moment came when Nehru stopped at her table and shook her hand....

At this time, Kashmir was emerging from a long period of isolation and popular politics was taking root. The maharaja, Hari Singh, was a Hindu and, in the eyes of most Kashmiris, an outsider, while his princely state was largely Muslim and the Kashmir Valley emphatically so. He was also part of a generation of Indian princes who were much more comfortable hunting, shooting and fishing than in engaging with social and political reform. The princely states were not formally part of the British Raj, but in Srinagar -- as in many other princely capitals -- a British Resident kept a careful watching eye and on occasions intervened to seek to ensure political stability and protect British interests. Princely autocracy and the accompanying restraints on political activity and public expression were increasingly an anachronism as the temper of Indian politics began to rise. Sheikh Abdullah and a like-minded group of young, educated Kashmiris -- most of them from the state's Muslim majority -- sought to challenge the oppressive feudalism still prevalent in the villages and to mobilise public opinion.

The Bedis came to see the Kashmir Valley not simply as a picturesque location offering respite from the summer heat but as the site of a political struggle to which they could, and should, contribute. This was probably a mix of personal initiative and prompting by the Communist Party, which viewed Kashmir as a promising place to seek recruits and influence. Sheikh Abdullah had a firm personal friendship and political alliance with the Congress's Jawaharlal Nehru, himself of distant Kashmiri descent. But the communists were keen to help support Abdullah's party, the National Conference, and shape its policy and strategy. When in the summer of 1942 Bedi was released from Deoli and Freda was able to disengage from her lecturing job in Lahore, their involvement in Kashmiri politics stepped up....

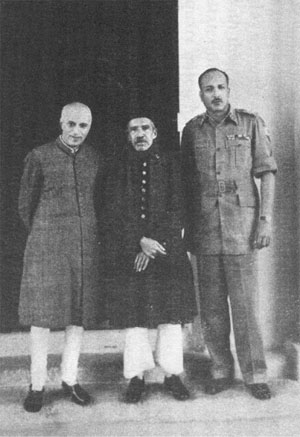

The reputation Bedi gained for taking the lead in compiling the 'New Kashmir' manifesto helped him in his task of securing recruits. Christabel Taseer saw at close quarters Bedi's effectiveness -- she recounted that G.M. Sadiq, later a prime minister of the state, 'was motivated to be a Leftist, as were a number of other young Kashrniris, by association with B.P.L. Bedi and his wife, Freda, both dedicated Marxists.' Another Kashmiri leftist with a large popular following, G.M. Karra, told Taseer how he and several others had been 'won over to the Communist cause through the Bedis'. Yet another stated that 'Kashmir's Marxist intellectual scene was dominated by B.P.L. Bedi and his English wife Freda Bedi'. The Bedis were big fish in the small pond of Kashmiri progressives and radicals -- and their close friendship with Sheikh Abdullah and his reliance on the left for strategic direction and organisational support gave them huge authority and influence. At the same time, the Bedis were making friends in the political mainstream of the nationalist movement too. A remarkable group photograph survives, taken in Kashmir in 1945 at the annual session of the National Conference, which includes three future prime ministers of India and two future prime ministers of Indian Kashmir: Sheikh Abdullah and his ally Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad are at the back; in front of them are Jawaharlal Nehru -- recently released from detention -- and his daughter Indira Gandhi; two nationalist leaders in what became Pakistan are prominent, Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai from Baluchistan and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan from the Frontier, the latter carrying a young child, very probably Indira's son, Rajiv Gandhi; on one flank is Mridula Sarabhai, an influential supporter of Kashmiri nationalism; on the other is Freda Bedi, smiling broadly and clearly pregnant, with B.P.L. behind her, largely hidden to the camera....

The women's militia in which Freda enrolled was one of a number of left-inspired initiatives to support Kashmir's progressive government and its ambitions for social change. The men's militia, replete with a political officer, saw active service alongside Indian troops and several of its members were killed. A cultural front encompassed progressive writers and poets from Kashmir and other parts of India and performed hastily written agitprop theatre. 'The atmosphere reminded one of Spain and the International Brigade,' one of the participants recalled a touch romantically, 'where, it was said, writers had come to live their books, and poets had come to die for their poetry!'

The Women's Self-Defence Corps was, as its name suggests, not intended as an offensive force but to help defend Srinagar, and particularly to protect the honour of its women. The numbers enrolling were modest and disproportionately from the Pandit, or Kashmiri Hindu, minority -- reflecting the social conservatism of the Muslim community and the preponderance of Pandits in the local intelligentsia and the left. The women were provided with rifles and trained in their use by an Indian army officer; they drilled and paraded in Srinagar's parks and open spaces. An armed women's militia would have been a striking innovation in any part of India -- in the conservative and sheltered Kashmir Valley, it reflected a revolution in social attitudes. The Communist Party paper, the People's Age, gave proud prominence to the militia. 'I am writing this letter from the Paladium [sic] Cinema which is our headquarters now,' one woman volunteer wrote. 'Down below at the crossing, thousands of Kashmiris are always mounting guard with their rifles. The whole city is mad with joy ... Today four of us girls will be taught the use of rifles. Tomorrow we may be sent to the ... front as field-nurses.' A subsequent issue featured two pages of photographs of the women in training, and declared: 'The women in Kashmir are the first in India to build an army of women trained to use the rifle. By their example they have made Indian history, filled our chests with pride, raised our country's banner higher among the great nations of the world.'

The women's militia never saw active service, though it paraded for and was inspected by Jawaharlal Nehru, now India's prime minister, on his visits to Srinagar. Pathe newsreel footage from 1948 includes a glimpse of Freda on the parade ground with a rifle in her hand. The volunteers also took on a social role, helping those displaced both by Partition-related upheaval and by the fighting in parts of the former princely state which came to involve the Pakistan army as well as irregular forces. They took up 'women's work' among the refugees, organising milk for the camps, and distributing clothes and blankets, 'all of us,' Freda told friends, 'acting as older sisters to the thousands of children and women suffering not only physical hardships in the desperate cold, but often in mental torture when relations and children had been killed, abducted, or lost on the miserable trek to safety.'....

The impact of the conflict over Kashmir pervaded Freda's letters -- 'we are a battle front' she told Olive Chandler -- and while a United Nations-brokered ceasefire came into effect at the close of 1948, Kashmir's contested status cast a shadow on the social ambitions of its governing party:While a very brutal tribal invasion + hot propaganda from the Pakistan side has been trying to make the State communal minded, it has valiantly stuck to its democratic ideas, + built up a corner of India where one can truly sayan inter-communal life exists. Something to be deeply grateful for after the inevitable frustration + bitterness that followed in the wake of the riots both in India + Pakistan.

All I had by way of books + household goods was either looted in Lahore, or is stored there ... + I can't get it. We had to rebuild from the ground up. But nothing matters -- all of us are safe + having been daily with refugees with their heartrending stories of violent death + abduction I feel we have been lucky.

She went on to reflect on the prospect of a popular vote to decide whether Kashmir should be part of India or Pakistan -- a commitment that Nehru had made to Kashmiris, though neither he nor subsequent Indian leaders have honoured it. 'Living in Kashmir is like sitting on the edge of a precipice,' she said....There will be a tough fight when + if a plebiscite takes place. The other side uses low weapons: an appeal to religious fanaticism + hatred which can always find a response. We fight with clean hands. I am content as a democrat that Kashmir should vote + turn whichever way it wishes: but I know a Pakistan victory would mean massacre, abduction, the mass migration of Hindus + Sikhs + I hate to face it. God forbid it should happen. Kashmir with its Socialist Government + its young leaders can lead India, rebuild this miserable Country. I've great faith in it, + love for it, too. It is beautiful, rich in talent + natural resources.

Nehru also pressed Sheikh Abdullah to keep communists at a distance, with Bedi the main target of his displeasure. In May 1949, after a brief visit to Kashmir, Nehru wrote to 'Shaikh Saheb' with a gentle warning:Quite a number of our embassies here are greatly worried at, what they say, the communist infiltration into Kashmir .... Most of them have heard about Bedi and they enquire about him. I understand that Bedi is editing the newspaper there and is drawing a substantial salary plus free car etc. I have no personal grievance against Bedi, but in view of the trouble we are having with the Communist Party in India, naturally Bedi's name is constantly coming up before people here.

Sheikh Abdullah's reply isn't available -- but Nehru wouldn't let the matter rest. He wrote again to the Kashmiri leader:You referred to the Bedis. I rather like them and especially Freda. I know that Freda left the Communist Party some years ago. What she has done since, I do not know. But so far as I know, Bedi has continued in the Party, and the Party, especially today, does not tolerate any lukewarm people or those who do not fall in line with their present policy.

I do not want you to push out the Bedis and cause immediate distress to them. But I do think that no responsible work should be given to them and they should be kept completely in the background. Yesterday I saw a little book on you written by the Bedis. This kind of thing immediately makes people think that the Bedis are playing a prominent role in Kashmir and are closely associated with you. These create reactions in their minds against you and your Government.

The publication which had attracted Nehru's attention was a twenty-page pamphlet in praise of Sheikh Abdullah. This unsophisticated piece of propaganda written jointly by the Bedis sought to portray the Kashmiri leader as one of 'the Great Three' figures of India's independence era alongside Nehru and Gandhi -- a theatrical over-statement which should have brought a blush to the authors' cheeks.

B.P.L. Bedi was aware of Nehru's antipathy and of the attempts to marginalise him. He said there was 'very great pressure ... exerted by the Government of India for my being sent away from Kashmir, because they felt leftist policies would be going on more and more adamantly if I stayed on there.' His influence and access started to diminish. Bedi was removed from his counter-propaganda role and deputed to Kashmir's education ministry to revise school textbooks. Freda was also involved (and probably more active) in drafting new textbooks and both husband and wife were nominated to Jammu and Kashmir's Central Advisory Board on Education. 'Over 90 books were rewritten and printed .. .' Freda commented, 'and Kashmir was the first part of India to reorganise its teaching material so that the books fitted in with the new world and the new free India that our children now live in.' These were important tasks but at some remove from the most sensitive political decision making. Nehru's advice, it seems, was being heeded. For Bedi, this sidelining must have added to a sense of anguish. After almost twenty years of incessant political activity, both the main political forces to which he had owed allegiance -- the Communist Party and the Kashmiri nationalists -- were cutting him loose. He had seen himself as a key and perhaps indispensable figure; that's not quite how others viewed him....

The Bedis also had a more active social life during their years in Srinagar than probably at any other time of their marriage. They enjoyed their status and the attention that surrounded it -- which stemmed both from their association with Sheikh Abdullah and Freda's exceptional position as a white woman who entirely identified with India and with Kashmiri nationalism. Michael Brecher, a Canadian academic, spent three months in Srinagar with his wife in the summer of 1951 and saw a lot of the Bedis. He found them both compelling but 'very different in almost every respect'. B.P.L. was clearly well connected, though a touch arrogant -- 'someone who could be very jovial and charming' but also 'a very serious committed ideologue'. He took more to Freda, 'a striking looking person, a very handsome lady ... most impressive as a human being: bright, engaged, caring'. He considered her a 'dual character -- being very British, it seemed to us' but totally immersed in her environment. Brecher came across a constant stream of visitors to the Bedis' home, including a woman he met in their garden who was 'very quiet, demure, almost inconspicuous'. This was Indira Gandhi, Nehru's only child, then in her mid-thirties. 'My sense from Freda was they were good friends.' The friendship nurtured in Kashmir between Indira and Freda, both Oxford graduates, strengthened over the following decade....

Towards the close of the Bedis' time in Kashmir, she accepted a six months' United Nations posting to Burma, which had won its independence from Britain a year after India. She could probably sense that her husband wouldn't continue for much longer at Sheikh Abdullah's side, and the family needed an income....

Freda's new role with the United Nations was to help in the planning of Burma's social services: 'A job after my own heart,' she told Olive Chandler, 'but it's hard not to be with the family. However, in their interest, I can't throw opportunities away + this opens new fields for us all.' She was restless by nature and relished the opportunity of working somewhere new. 'Burma is like India enough to be homely,' she wrote, 'unlike enough to be beguiling.' Without family responsibilities, she had more time to devote to her own interests, and above all to meditate. She met a Buddhist teacher in Rangoon, U Titthila, who had spent the war years in London where he had on occasions abandoned his monk's robes to serve as an air raid warden and, during the Blitz when London came under sustained German air attack, as a stretcher bearer. Freda found him 'very saintly'; she asked him to teach her Vipassana (insight) meditation techniques. 'And it was then ... I got my first flash of understanding -- can't call it more than that. But it changed my whole life. I felt that, really, this meditation had shown me what I was trying to find ... and I got great, great happiness -- a feeling that I had found the path.'...

For two months, she had a weekly session with U Titthila. 'And I remember him saying when the eight weeks was coming to an end: if you get a realisation or a flash of realisation, it may not be sitting in your room in meditation, in pose in front of a picture of the Buddha or something, it will probably be somewhere where you don't expect it.' That's exactly what happened. 'I was actually walking with the [UN] commission through the streets of Akyab in the north of Burma -- [it was] as though some gates in my mind had just opened and suddenly I was seeing the flow of things, meaning, connections. And when I went back to Delhi, well, I told my husband I'd been searching all my life, it's the Buddhist monks who have been able to show me something I could not find and I'm a Buddhist from now on. Then I began to learn Buddhism after that.' Her family's recollection is that this 'flash' of spiritual awakening was accompanied by a breakdown. According to Ranga, his mother fainted and was taken to hospital. Bedi managed to get emergency travel documents, headed out to Burma and brought his wife home. When she came back, she didn't recognise B.P.L. or anybody. She didn't recognise her children. She would sit on her cot doing nothing -- completely blank. You couldn't make eye contact with her,' Ranga recalls. 'There was no speech, no recognition-though she could eat and bathe. That lasted for about two months when she gradually started reacting to things. All she recalled was that when walking down the street ... she saw a huge flash of light in the sky and she lost consciousness.'....

On her return to Delhi, she set up an organisation that she called the Friends of Buddhism. She took a personal vow of brahmacharya, a commitment to virtuous living which implies a decision to become celibate. Her engagement with the faith radically refashioned her links with her family and set her on the course which defined the last quarter-of-a- century of her life....

Once she was fully recovered, Freda again had to take on the responsibility of being the family's primary earner. She got a helping hand from a well-placed friend. Among her papers is a handwritten note from 'Indu', Indira Gandhi, on the headed paper of the Prime Minister's House: 'Durgabai Deshmukh wants to see you at 11 a.m. tomorrow ... in her office in the Planning Commission, Rashtrapati Bhawan. I shall send the car at 10.30.' Deshmukh was an influential figure in the Congress Party and had been a member of India's Constituent Assembly. She had just been appointed as the initial chairperson of the Planning Commission, which in Nehruvian India with its faith in the state to engineer social and economic progress was an important post. She was adamant on the need to champion the interests and promote the welfare of women, children and the disabled. Her meeting with Freda clearly went well. The following month, in January 1954, Freda began working for the government's Central Social Welfare Board establishing and editing a monthly journal, Social Welfare. Although she was not a natural civil servant, she embraced the social agenda and the opportunity to travel across India and throw a spotlight on women's concerns and on projects which successfully addressed them. She remained in the job for eight years....

The late 1950s were a period of transition for the Bedi family. Bhabooji, Baba's mother and a constant in Freda's life ever since she had arrived in India, died in August 1958. She was told just before her death that Ranga had got engaged. He had spent a year or two with friends farming on 600 acres of remote land near the border with Nepal -- and, for a second time in his life, living in huts without electricity or running water. That hadn't worked out, and he secured a job as an assistant manager on a tea estate in the far reaches of Assam, one of the first Indians to break into the hitherto 'ex pat' domain of tea planting. He and Urmila Paul, known universally as Umi, married in November. She was from a Christian family and they had a Christian wedding at her uncle's home in the Lodhi Estate in Delhi. Indira Gandhi attended and brought a note from her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, bestowing his blessings....

Towards the close of 1956, Delhi hosted a major international Buddhist gathering that was Freda's introduction to the Tibetan schools of Buddhism, which are in the Mahayana tradition as distinct from the Theravada school which is predominant in Burma. This Buddha Jayanti was to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the Buddha's life. The Indian government wanted Tibet's Buddhist leaders to attend, particularly the Dalai Lama, who was that rare combination of temporal ruler and spiritual leader of his people. The Chinese authorities initially said no but at the last minute relented. Jawaharlal Nehru was at Delhi airport to welcome the twenty-one year old Dalai Lama on his first visit to India; the young Tibetan leader had at this stage not made up his mind whether he would return to his Chinese-occupied homeland or lead a Tibetan independence movement in exile. Freda played a role in welcoming the Tibetan delegation to the Indian capital. 'The radiance and good humour of the Dalai Lama was something we shall never forget,' she told Olive Chandler. 'I also got a chance of shepherding the official tour of the International delegates to India's Buddhist shrines and made many new friends.' A snatch of newsreel footage shows Freda Bedi at the side of the Dalai Lama at Ashoka Vihar, the Buddhist centre outside Delhi where the Bedi family had camped out a few years earlier. Both Kabir and Guli were also there, the latter peering out nervously between a heavily garlanded Dalai Lama and her sari-clad mother.19 Freda also received the Dalai Lama's blessing.

In the following year, when she made a brief visit to Britain, Freda made a point of visiting the main Buddhist centres in London and meeting Christmas Humphreys, a judge who was the most prominent of the tiny band of converts to Buddhism in Britain. She was becoming well-known and well-connected as a practitioner of Buddhism. What prompted her to become not simply a devotee but an activist once more was the Dalai Lama's second visit to India -- in circumstances hugely different from his first. Nehru had dissuaded the Dalai Lama from staying in India after the Buddha Jayanti celebrations. Early in 1959, Tibet rose up against Chinese rule, an insurrection which provoked a steely response. The Dalai Lama and his retinue, fearing for their lives and for Tibet's Buddhist traditions and learning, fled across the Himalayas, crossing into India at the end of March and reaching the town of Tezpur in Assam on 18th April 1959. Tens of thousands of Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama, undergoing immense hardships as they traversed across the mountains and sought to evade the Chinese army. Freda felt impelled to get involved.

'Technically, I was Welfare Adviser to the Ministry,' Freda wrote of her time at the Tibetan refugee camps in north-east India; 'actually I was Mother to a camp full of soldiers, lamas, peasants and families.' It was a role she found fulfilling. Freda was able to use the skills and contacts she had developed as a social worker and civil servant and at the same time to be nourished by the spirituality evident among those who congregated in the camps. The needs of the refugees were profound. For many, the journeys had been harrowing -- avoiding Chinese troops, travelling on foot across the world's most daunting mountain range and sometimes reduced to eating yak leather to stave off starvation. Many failed to complete the journey. And while the Indian camps offered sanctuary, they were insanitary, overcrowded and badly organised. For hundreds of those who arrived tattered, malnourished and vulnerable to disease, the camps were places to die.

In October 1959, six months after the camps were set up, Jawaharlal Nehru, India's prime minister, asked Freda to visit them and report back -- though it may be more accurate to say that Freda badgered her old friend into giving her this role....

Her most immediate task was to remedy the shortcomings in the running of these hastily set-up camps. She used the privileged access she had to India's decision makers. She went straight to the top -- to Nehru. And he listened. In early December, Nehru sent a note to India's foreign secretary, the country's most senior career diplomat, asking for a response to concerns that Freda had brought to the prime minister's notice. He endorsed one of Freda's suggestions, 'the absolute necessity of social workers being attached to the camps'.The normal official machinery (Nehru wrote) is not adequate for this purpose, however good it might be. The lack of even such ordinary things as soap and the inadequacy of clothing etc. should not occur if a person can get out of official routines. But more than the lack of things is the social approach.

What concerned Nehru even more was Freda's complaint of endemic corruption. 'She says that "I am convinced that there is very bad corruption among the lower clerical staff in Missamari [sic]". Heavy bribery is referred to. She suggested in her note on corruption that an immediate secret investigation should take place in this matter.' Nehru ordered action to investigate, and if necessary to remove, corrupt officials. 'It is not enough for the local police to be asked to do it,' he instructed. It's not clear what remedial measures were taken but the interest in the running of the Tibetan camps shown by the prime minister and by his daughter, Indira Gandhi, will have helped to redress the most acute of the problems facing the refugees there....

Towards the close of her six months in the camps, Freda Bedi again sought out Nehru, and this time was more insistent about the measures the Indian government needed to take to meet its responsibilities towards the refugees. She wrote to the prime minister to pass on the representations of 'the representatives of the Venerable Lamas and monks of the famous monasteries ... living in Misamari', though the vigour with which she expressed herself -- this was not the temperately worded letter that India's prime minister would be more accustomed to receive -- underlines her own anger at what she saw as the harsh treatment of the Tibetan clerics in particular. Her main concern was the enrolling of Tibetan refugees on road building projects.Roadwork is heaving, exhausting, and nomadic, it is utterly unsuited to monks who have lived for long years in settled monastic communities. They can't 'take it', any more than could our lecturers, or officials, or Ashramites, or university faculties and students. Let us face that fact, and make more determined efforts to rehabilitate them in their own groups on land.

She insisted that those who did not offer to do roadwork were not lazy, and that almost all those in the camps were 'eager and willing to work on land in a settled Community'. And she sought lenience for some of those involved in roadwork who were penalised as 'deserters' when they were forced to leave their duties because rain washed away the roads or had made shelter and food supplies precarious. 'I feel it is not worthy of Gov[ernmen]t to be vindictive when the refugees have already suffered as much in Tibet,' she told Nehru. 'We should be big hearted.'

She warned Nehru that the Indian government's responsibility for Tibetan monks wasn't limited to the 700 or so in Dalhousie in the north Indian hills and the 1,500 which at this date -- March 1960 -- were at Buxa. There were a further 1,200 monks in Misamari and new arrivals expected for some months more, and another 1,500 refugees outside the government camps living in and around the Indian border towns of Kalimpong and Darjeeling and 'in a pitiable condition'. Freda was speaking from personal observation. Her letter concluded with an appeal and a warning, again couched in language that only a personal friend could use to address a prime minister:Panditji, I am specially asking your help as I do not want a residue of over one thousand unhappy lamas and monks to be left on our hands when Misamari closed. Nor do I want to hear totally unfair statements that 'they won't work'. I am sure you will help to clarify matters in Delhi.

Nehru asked his foreign secretary to investigate, who replied with a robust defence of the use of refugees in road-building projects. They were not acting under compulsion, he insisted, and this was a temporary measure while more permanent arrangements were made for accommodation and rehabilitation. And he suggested that some at least of the refugees were work shy, expressing just the sort of view that Freda had insisted was so unjust and uncaring. 'Mrs Bedi complains that we have been hard on the Lamas,' the foreign secretary wrote in a note to Nehru. 'There are various grades of Lamas, from the highly spiritual ones -- the incarnate Lamas -- to those who merely serve as attendents [sic]. Our information now is that having found life relatively easy ... many ordinary people who would otherwise have to earn their living by work, are taking to beads and putting forward claims as Lamas. I feel that some pressure should be brought to bear on this kind of people to do some useful work.'

In her letter to the prime minister, Freda had mused that if Nehru could see the Buxa and Misamari camps, 'I feel you would instinctively realise the major unsolved policy problems here on the spot.' In a testament to her personal sway with India's leader, the following month Nehru did indeed visit Misamari. He spent two hours at the camp, looking round the hospital and seeing Tibetan girls who were being trained in handloom weaving. He addressed a crowd which consisted of almost all the 2,800 Tibetans then at Misamari, assuring them that he would act on an appeal he had received from the Dalai Lama to extend arrangements for educating both the young and adults. There was no greater spur to official attention to the Tibetans' welfare than the prime minister's personal oversight of the issue. And if any had doubted just how much influence Freda held with the prime minister, persuading him to travel across the country to one of its most difficult-to-reach corners demonstrated just how influential and effective she was.

Freda did not let the matter drop. On her return to Delhi in June, she called on the prime minister and in a remarkable demonstration of her moral authority and personal influence, cajoled Nehru to write to one of his top civil servants that same evening to express his disquiet about what he had heard concerning recent ministry instructions.One is the order that all the new refugees, without any screening, should be sent on somewhere for road-making, etc. This seems to me unwise and impracticable. These refugees differ greatly, and to treat them as if they were all alike, is not at all wise. There are, I suppose, senior Lamas, junior Lamas, people totally unused to any physical work etc. ...

Sending people for road-making when they are entirely opposed to it, will probably create dis-affection in the road-making groups which have now settled down more-or-less. I was also told that the mortality rate increases.

It reads almost as if Freda was dictating the prime minister's note. She also prompted Nehru to question a reduction in rations for those in the camps, and to urge the provision of wheat, a much more familiar part of the Tibetan diet, rather than rice. Freda Bedi was, Nehru warned, going to call on the ministry the following day -- and civil servants were urged to take immediate action on these and any other pressing issues she raised. 'I do not want the fairly good record we have set up in our treatment of these refugees,' the prime minister asserted, 'to be spoiled now by attempts at economy or lack of care.'

Nehru's more persistent concern was the impact of providing refuge to the Dalai Lama and so many of his followers on relations with India's powerful eastern neighbour. A steady deterioration in relations eventually led to a short border war in 1962 which -- to Nehru's shock and distress -- China won. In the immediate aftermath of that military setback, Nehru came to address troops at Misamari camp, which had reverted to serving as a military base. Nevertheless, India persisted with its open-door policy for Tibetans, and somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 refugees followed the Dalai Lama into India. The Dalai Lama and his immediate entourage were settled in the hill town of Dharamsala in north India, which became the headquarters of Tibet's government-in-exile. One of Freda's more quixotic interventions with Nehru was to argue that the Dalai Lama and his entourage should remain in their temporary home in the hill resort of Mussoorie rather than relocated to Dharamsala. Nehru replied that he found her arguments 'singularly feeble'.

Freda found her time in the Assam camps both physically and emotionally draining. On her return to Delhi she was admitted to hospital suffering from heat stroke and exhaustion. It was sufficiently serious for Kabir and Gulhima to be brought down from their boarding school in the hills. The doctors said their presence might lift her spirits. 'She responded well to our being there,' Gull says. 'Initially when we went in to see her she did not respond. But the next day she was sitting up and spoke.' Once recovered, she was determined to have a continuing role promoting the welfare of Tibetan refugees even though she was returning to her government job editing Social Welfare. Reading between the lines of Nehru's missives, Freda seems to have lobbied him on this point. 'If possible, I should like to take advantage of her work in future,' Nehru noted. 'She knows these refugees and they have got to know her. Could we arrange with the Central Social Welfare Board to give her to us for two or three weeks at a time after suitable intervals?'

When Freda confided to her friend Olive Chandler that her heart was in working with the Tibetans, she was saying what was becoming increasingly evident to her colleagues in the Social Welfare Board. 'Freda went to these camps and her heart bled,' according to her friend and colleague Tara All Baig. 'She neglected her work with the Board more and more, travelling to the centres especially in Bengal and Dehra Dun where distress was greatest.' Her boss, the formidable Durgabai Deshmukh, got fed up with Freda's preoccupation with the Tibetan issue to the exclusion of other aspects of her work. She was determined to sack Freda, and only Baig's personal intervention saved her job. 'I was lashed by Durgabai's best legal arguments against retaining her. But Freda had children and needed her job. I weathered the storm and was rewarded with Freda's reinstatement.' She survived in her government post for another couple of years, by which time the pull of working more fully and directly with the lamas among the Tibetan refugees had become compelling.

In her letters and representations to Nehru about conditions in the Tibetan camps, Freda raised an issue about the treatment of the monks and lamas which became for her a mission. 'We are not trying seriously or systematically to send them to educational institutions to teach them English or Hindi or the provincial regional languages, without which they cannot be suitably rehabilitated,' she lamented. 'A small number should be sent now so that they can, after about 1-2 years, return to their monasteries/farms and teach the others.' Nehru, once again, endorsed Freda's suggestion and passed it on to civil servants, insisting that 'some priority' must be given to arranging teaching of languages in the camps, and to adults as well as children. Freda understood that there would be no early return to Tibet for the refugees and if the spiritual tradition which she and the Tibetans so greatly valued was to survive, then it would need to adapt to its new surroundings. She also wanted the world to appreciate Tibetan Buddhism and to have access to its richness -- to share her discovery and the joy that it brought. And for both these goals, that meant educating the coming generation of spiritual leaders -- not simply ensuring that their religious instruction and guidance continued in their new home, but that they gained proficiency in English and Hindi....

Of all the ventures that Freda Bedi embarked upon in her varied life, the Young Lamas' Home School has borne the biggest legacy....

Lang-Sims saw at close quarters the setting up of the Home School. The house was newly built with stone floors, standing on raised ground on an 'exceptionally pleasant' site amid an expanse of scrubland....

Freda's energy, drive and organisation had established the school and marshalled the young lamas. She was every bit as effective at developing the profile of the new school, which was so important in ensuring continued government support and private fundraising. With an eye perhaps on both goals, Freda took Lois Lang-Sims to meet Nehru, then in his early seventies and increasingly worn-out after fourteen years in office. 'Freda expressed her gratitude for his encouragement and assistance in her school project: suddenly he really smiled, seeming to wake out of his dream, and said teasingly, in a very low, quiet voice: "It was not for you I did it." Then he half closed his eyes and appeared almost to go to sleep.'

-- The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

Men often call themselves progressive when they only mean that they are not reactionary. Progressive men start and lead progressive movements like the many we have seen spring up around us all over the world in the last two decades. Some of these progressive movements have had a great fascination for Nehru. He always likes to be looked upon as a modern; he wants to be a Picasso hung up in the Royal Academy, looking upon the classical forms around him with a supercilious air. He is easily moved by the righteousness of a cause and by anything that smacks of a crusade. He always comes back from his trips abroad full of admiration for some other people in some other part of the world who may be fighting their battle for freedom, whether that battle is to achieve freedom or to retain it. He is fond of reading literature which speaks the language of freedom. All this has endeared him to our people, to whom he is more a legend than a practical leader. In terms of folklore, he could be likened to a prince, ready with his sword to defend the unarmed, to guard the rights of man, to fight for human justice. But all this Tennysonian allegory of the days of King Arthur and Lancelot does not sit so well at the desk of the Prime Minister of India, more especially when this knight with the shining piece of steel has constantly got to dip it in ordinary blue-black ink to append his signature to executive actions, some of which could be likened to those of a small-town dictator in a neo-fascist state. That new streak, perceptible in Jawaharlal Nehru, some say has come with responsibility; others strongly suspect it has come with power.

To understand this, one has to go back fifteen years, when, in the staid Modern Review [1. November 1937.] of Calcutta, a magazine which circulates among ‘highbrows’ only, there appeared an article, anonymously written, entitled ‘Jawaharlal Nehru’. Readers of the Modern Review were disturbed by the appearance of this ridiculously melodramatic article in an otherwise weighty publication. The author was obviously an enthusiastic college student whom the editor was trying desperately hard to encourage. Nehru was at that time President of the Indian National Congress, and he had indicated his unwillingness to carry on the appointment for another term. The young writer was trying to dissuade the Congress from reelecting him, on the grounds that in Jawaharlal was the germ of a fascist, and that if he were pampered too much, the pampering would go to his head. Of course, he wrote in glowing terms about Jawaharlal all the way through the article, as some of the passages quoted below will indicate:

‘ . . . The Rashtrapati [2. Sanskrit word for President.] looked up as he passed swiftly through the waiting crowds, his hands went up and were joined together in salute and his pale hard face was lit up by a smile. It was a warm personal smile, and the people who saw it responded to it immediately and smiled and cheered in return.

‘The smile passed away and again the face became stern and sad, impassive in the midst of the emotion that it had roused in the multitude. Almost it seemed that the smile and the gesture accompanying it had little reality behind them; they were just tricks of the trade to gain the goodwill of the crowds whose darling he had become. Was it so?

‘Watch him again. There is a great procession, and tens of thousands of persons surround his car and cheer him in an ecstasy of abandonment. He stands on the seat of the car, balancing himself rather well, straight and seemingly tall, like a god, serene and unmoved by the seething multitude. Suddenly there is that smile again, or even a merry laugh, and the tension seems to break and the crowd laughs with him, not knowing what he is laughing at. He is god-like no longer but a human being, claiming kinship and comradeship with the thousands who surround him, and the crowd feels happy and friendly and takes him to its heart. But the smile is gone and the pale stern face is there again . . .

Jawaharlal is a personality which compels interest and attention. But they have a vital significance for us, for he is bound up with the present in India, and probably the future and he has the power in him to do great good to India or great injury ....

‘ . . . From the far north to Cape Comorin he has gone like some triumphant Caesar passing by, leaving a trail of glory and a legend behind him. Is all this for him just a passing fancy which amuses him, or some deep design or the play of some force which he himself does not know? Is it his will to power of which he speaks in his autobiography that is driving him from crowd to crowd and making him whisper to himself: “I drew these tides of men into my hands and wrote my will across the sky in stars”?’

Then came the young writer’s warning:

‘. . . Men like Jawaharlal with all their capacity for great and good work are unsafe in a democracy. He calls himself a democrat and a socialist, and no doubt he does so in all earnestness, but every psychologist knows that the mind is ultimately a slave to the heart and that logic can always be made to fit in with the desires and irrepressible urges of man. A little twist and Jawaharlal might turn into a dictator, sweeping aside the paraphernalia of a slow-moving democracy. He might still use the language and slogans of democracy and socialism, but we all know how fascism has fattened on this language and then cast it away as useless lumber.' (The italics are mine.)

On the other hand, the writer went on to say, ‘Jawaharlal is certainly not fascist either by conviction or by temperament. He is far too much of an aristocrat for the crudity and vulgarity of fascism ...’ Since when has aristocracy been a bar to fascism? In fact, history proves that it has fostered it. But when an editor decides to encourage a young man who fancies he has a flair for writing, it would be pointless to mutilate the script on grounds of historical accuracy. So the Modern Review printed this effusion, obviously without any sub-editing.

Soon the young writer was becoming wobbly. He could not make up his mind about Jawaharlal, and ended by proving that Jawarharlal could not become a fascist but that he would! The passages in the article that followed read:

‘Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. And yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him -- vast popularity, strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and certain contempt for the weak and inefficient. His flashes of temper are well known, and even when they are controlled, the curling of the lips betrays him. His overmastering desire to get things done, to sweep away what he dislikes and build anew, will hardly brook for long the slow process of democracy. He may keep the husk but he will see to it that it bends to his will. In normal times he would just be an efficient and successful executive, but in this revolutionary epoch, Caesarism is always at the door, and is it not possible that Jawaharlal might fancy himself as a Caesar?

‘Therein lies danger for Jawaharlal and for India. For it is not through Caesarism that India will attain freedom, and though she may prosper a little under a benevolent and efficient despotism she will remain stunted, and the day of emancipation of her people will be delayed . . .

‘Let us not . . . spoil him by too much adulation and praise. His conceit, if any, is already formidable. It must be checked. We want no Caesars.’

This quite incredible article, which read like a rough shooting script for a Cecil B. De Mille version of an Indian Quo Vadis, was obviously not taken seriously by anyone except the author himself. It certainly made no difference whatsoever to the Indian National Congress, which voted Jawaharlal as President despite all warnings.

Imagine our surprise when some years later it was revealed that the author of this anonymous absurdity was none other than Jawaharlal Nehru himself....

The people of the world are accustomed to see Pandit Nehru as he appears in their capitals, with a pleasant, friendly grin on his face, stretching out his hand for a warm handshake or joined in the Indian manner of namaskar. They know him as the essence of gentility, a humble little Pandit from India, educated at Harrow and Cambridge. But that is not the Nehru we know. There is very little humility in him now, and even the little he had learned from Mahatma Gandhi is hardly to be evidenced these days. Nehru’s concept of humility is that the Indians should gather to acclaim him as the greatest of them all, and that he should try to dissuade them from such a process of thought. The article which Pandit Nehru wrote on himself in the Modern Review appears to substantiate this view.

There is nothing humble about the way he runs his cabinet; to his ministers he is like a schoolmaster taking his class. Only two of his colleagues, Maulana Azad and Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, exercise any influence over him. Of the rest, two more, Deshmukh and Gopalswamy Ayangar, stand on their dignity, but most of the others who theoretically share joint cabinet responsibility according to the parliamentary convention, find moron-like agreement with their Prime Minister, once he expresses a definite view. A grunt from Nehru produces immediate acceptance of an idea. A dissenting opinion, apologetically expressed and prefaced by: 'I wonder, Mr Prime Minister, whether we should not also consider . . .’ produces a look of disgust on his face, which indicates how utterly stupid the Prime Minister regards such a suggestion to be, and, if occasion arises, Pandit Nehru is not unwilling to say it in so many words. The more ambitious anglers for power, which can only emanate from his authority, now spend their time trying to forecast how he is likely to react on any matter which they may have to discuss with him.

-- Nehru: The Lotus Eater From Kashmir, by D.F. Karaka

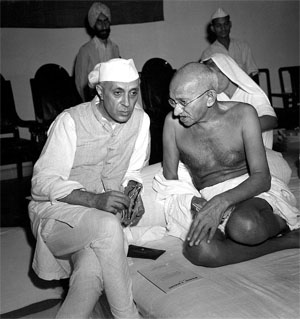

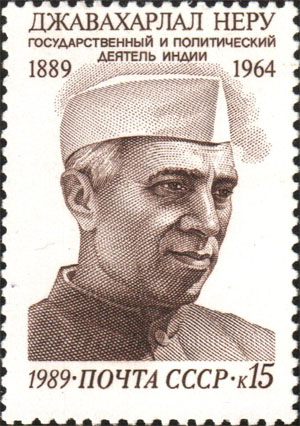

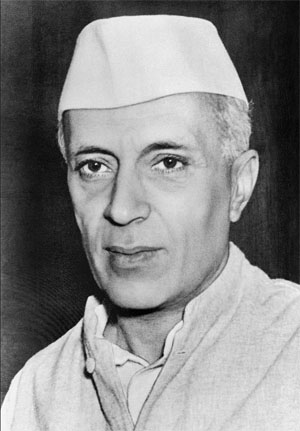

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru

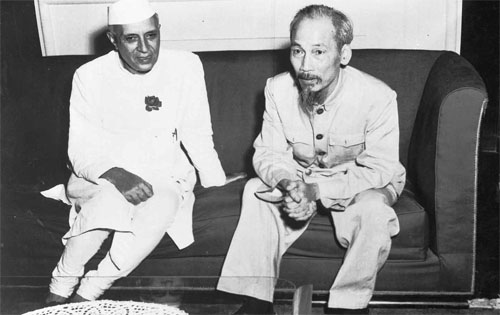

Jawaharlal Nehru in 1947

1st Prime Minister of India

In office: 15 August 1947 – 27 May 1964

Monarch: George VI (until 26 January 1950)

President: Rajendra Prasad; Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Governor General: The Earl Mountbatten of Burma; Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (until 26 January 1950)

Deputy: Vallabhbhai Patel (until 1950)

Preceded by: Position established

Himself as Vice President of the Executive Council

Succeeded by: Gulzarilal Nanda (Acting)

Minister of Defence

In office: 31 October 1962 – 14 November 1962

Preceded by: V. K. Krishna Menon

Succeeded by: Yashwantrao Chavan

In office: 30 January 1957 – 17 April 1957

Preceded by: Kailash Nath Katju

Succeeded by: V. K. Krishna Menon

In office: 10 February 1953 – 10 January 1955

Preceded by: N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar

Succeeded by: Kailash Nath Katju

Minister of Finance

In office: 13 February 1958 – 13 March 1958

Preceded by: Tiruvellore Thattai Krishnamachariar

Succeeded by: Morarji Desai

In office: 24 July 1956 – 30 August 1956

Preceded by: Chintaman Dwarakanath Deshmukh

Succeeded by: Tiruvellore Thattai Krishnamachariar

Minister of External Affairs

In office: 2 September 1946 – 27 May 1964

Preceded by: Position established

Succeeded by: Gulzarilal Nanda

Vice President of Executive Council

In office: 2 September 1946 – 15 August 1947

Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha

In office: 1952-1964

Preceded by: constituency established

Succeeded by: Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit

Constituency: Phulpur, Uttar Pradesh

Personal details

Born: 14 November 1889, Allahabad, North-Western Provinces, British India (present-day Uttar Pradesh, India)

Died: 27 May 1964 (aged 74), New Delhi, Delhi, India

Cause of death: Heart attack

Resting place: Shantivan

Political party: Indian National Congress

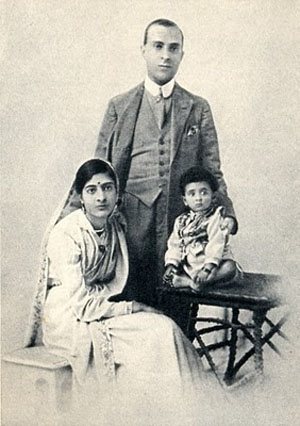

Spouse(s): Kamala Nehru (m. 1916; died 1936)

Children: Indira Gandhi

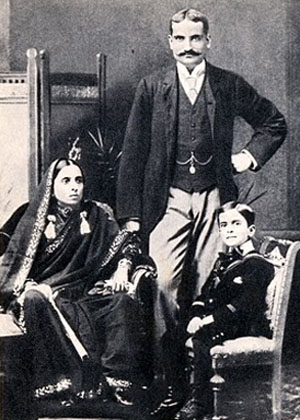

Parents: Pandit Motilal Nehru; Swarup Rani Nehru

Relatives: See Nehru–Gandhi family

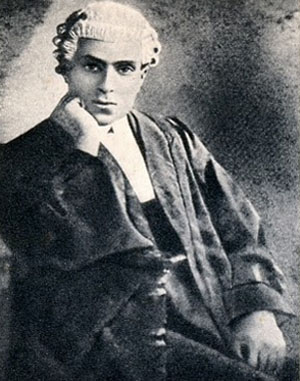

Alma mater: Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A.)

Inner Temple (Barrister-at-Law)

Occupation: Barrister writer politician

Awards: Bharat Ratna (1955)

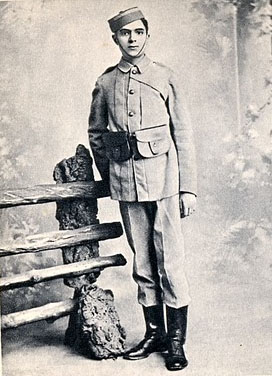

Jawaharlal Nehru (/ˈneɪruː, ˈnɛruː/;[1] Hindi: [ˈdʒəʋaːɦərˈlaːl ˈneːɦru] (About this soundlisten); 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian independence activist, and subsequently, the first Prime Minister of India and a central figure in Indian politics before and after independence. He emerged as an eminent leader of the Indian independence movement and served India as Prime Minister from its establishment as an independent nation in 1947 until his death in 1964. He has been described by the Amar Chitra Katha as the architect of India.[2] He was also known as Pandit Nehru due to his roots with the Kashmiri Pandit community while Indian children knew him as Chacha Nehru (Hindi, lit., "Uncle Nehru").[3][4]

The son of Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and nationalist statesman and Swaroop Rani, Nehru was a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge and the Inner Temple, where he trained to be a barrister. Upon his return to India, he enrolled at the Allahabad High Court and took an interest in national politics, which eventually replaced his legal practice. A committed nationalist since his teenage years, he became a rising figure in Indian politics during the upheavals of the 1910s. He became the prominent leader of the left-wing factions of the Indian National Congress during the 1920s, and eventually of the entire Congress, with the tacit approval of his mentor, Gandhi. As Congress President in 1929, Nehru called for complete independence from the British Raj and instigated the Congress's decisive shift towards the left.

Nehru and the Congress dominated Indian politics during the 1930s as the country moved towards independence. His idea of a secular nation-state was seemingly validated when the Congress swept the 1937 provincial elections and formed the government in several provinces; on the other hand, the separatist Muslim League fared much poorer. But these achievements were severely compromised in the aftermath of the Quit India Movement in 1942, which saw the British effectively crush the Congress as a political organisation. Nehru, who had reluctantly heeded Gandhi's call for immediate independence, for he had desired to support the Allied war effort during World War II, came out of a lengthy prison term to a much altered political landscape. The Muslim League under his old Congress colleague and now opponent, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had come to dominate Muslim politics in India. Negotiations between Congress and Muslim League for power sharing failed and gave way to the independence and bloody partition of India in 1947.

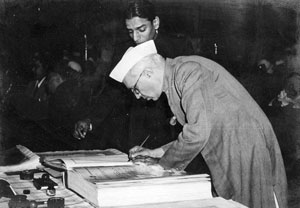

Nehru was elected by the Congress to assume office as independent India's first Prime Minister, although the question of leadership had been settled as far back as 1941, when Gandhi acknowledged Nehru as his political heir and successor. As Prime Minister, he set out to realise his vision of India. The Constitution of India was enacted in 1950, after which he embarked on an ambitious program of economic, social and political reforms. Chiefly, he oversaw India's transition from a colony to a republic, while nurturing a plural, multi-party system. In foreign policy, he took a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement while projecting India as a regional hegemon in South Asia.

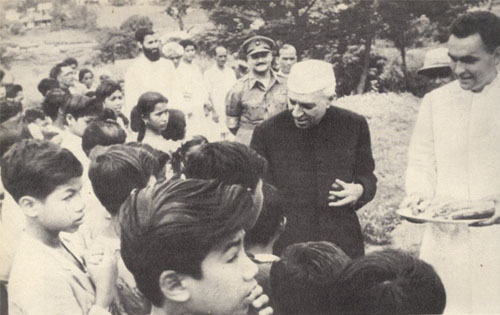

Under Nehru's leadership, the Congress emerged as a catch-all party, dominating national and state-level politics and winning consecutive elections in 1951, 1957, and 1962. He remained popular with the people of India in spite of political troubles in his final years and failure of leadership during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In India, his birthday is celebrated as Bal Diwas (Children's Day).